July 13, 2012

Air Date: July 13, 2012

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Keeping Emissions Down in California

View the page for this story

The California Air Resources Board has mandated that by 2025, 15 percent of new cars sold in the state must have zero or near-zero emissions. Daniel Sperling, the director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California Davis, tells host Bruce Gellerman how the state is going to achieve this goal. (07:45)

Cellulosic Fuel Update

View the page for this story

Five years ago, cellulosic ethanol seemed to hold a lot of promise. The only thing missing was the ramp up to commercial production. But, as Jeremy Martin of the Union of Concerned Scientists explains to host Bruce Gellerman, then the recession happened. (06:35)

Science Note/Bat Aerodynamics

/ Stephanie McPhersonView the page for this story

Bats fly through the air with the greatest of ease and new research shows that their flight is regulated by sensitive hairs on its wings. Stephanie McPherson reports. (01:45)

Chemicals and Health

View the page for this story

There are tens of thousands of chemicals in everyday products. Only a fraction of these have been tested for toxicity and health effects in the U.S. Host Bruce Gellerman talks to Richard Denison, a senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund, about news studies that raise troubling health questions. (09:30)

Bare Shoulders: Herbicide Along the Highway

/ Ingrid LobetView the page for this story

Highway departments across the nation put time, energy and resources into maintaining the side of the road, often preferring to keep it clean and clear of plants. But, as Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet reports, in Oregon, some residents don’t want chemicals used to keep the highway shoulders bare. (07:10)

BirdNote® What Do Birds Smell?

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

It’s summer and that means it’s time to wake up and smell the roses. And, as BirdNote®’s Michael Stein reports, birds are doing a lot of sniffing this time of year. (02:00)

Arctic Explorers

/ Emily CorwinView the page for this story

Few navigators have dared to travel the treacherous waters of Northern Canada that marooned Henry Hudson some 400 years ago. But as Mind Open Media’s Emily Corwin reports, a storyteller and a climate scientist have both taken on Arctic exploration as an interest and a challenge. (10:45)

Earth Ear

View the page for this story

(01:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bruce Gellerman

GUESTS: Daniel Sperling, Jeremy Martin, Richard Denison

REPORTERS: Ingrid Lobet, Emily Corwin

[THEME]

GELLERMAN: From Public Radio International - it's Living on Earth. I'm Bruce Gellerman. California puts the pedal to the metal. It’s requiring a percentage of new cars sold in the state be zero or near zero emission vehicles - and the car companies are on board.

SPERLING: There certainly has been a dramatic turn-around in the attitude of the automobile industry in the last few years. They see that this is inevitable, that there is a problem with oil, and even more important, there is a problem with climate change.

GELLERMAN: Also, four hundred years ago, Henry Hudson got stranded in an Arctic bay, and charting a course there is still a challenge today.

STRANEO: Every time I brought up Hudson Strait, everybody shook their head. It had a reputation for being a really tough place where to work.

GELLERMAN: And it is. Following in the ill-fated footsteps of the famed Arctic Explorer, and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

PRI ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

[THEME]

Keeping Emissions Down in California

Red taillights are a common sight on Los Angeles’ busy freeways. (Photo: Flickr Creative Commons, luxuryluke)

GELLERMAN: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville Massachusetts, this is a recycled edition of Living on Earth. I’m Bruce Gellerman. California has been crazy about cars for a long time. Now some are saying the state’s new auto emission and fuel standards take crazy to a whole new level. Professor Daniel Sperling is one of nine members on the California Air Resources Board. Last December the board unanimously approved strict standards limiting the amount of carbon in vehicle fuels.

SPERLING: So, really it is a big change. What it does is requires the oil companies to reduce the carbon in their fuel that they sell by ten percent by 2020. And that, perhaps, doesn’t sound like a big number, but to get that ten percent means probably about a third of their fuel has to be shifted away from petroleum.

And I have to say, myself as an academic, myself as a regulator, I don’t know how this is going to play out exactly. And that’s why these policies we’re talking about are performance-based and market-based. We’re leaving it to the market and consumers and industry to figure it out. A lot of that will be biofuel, some of it will be electricity, some of it will be natural gas. We’re talking about a transformation, a revolution here. And it’s really remarkable.

GELLERMAN: Well, not content with just that revolution, California's Air Resources Board is putting the pedal to the metal and requiring that, by 2025, 15 percent of new car sales in the state be either zero, or near-zero emission vehicles. Here again is Professor Dan Sperling.

Professor Daniel Sperling. (Photo: Daniel Sperling)

SPERLING: California is once again, for better or for worse, you know, plunging forward ahead of everyone else and we’re not telling companies exactly what technologies to use, but we’re expecting that of those vehicles, probably about a third to a half would be hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, a third to a half would be battery electric vehicles, and the rest would be plug-in hybrid electric vehicles.

GELLERMAN: But of course, there are very few hydrogen gas stations now.

SPERLING: That’s right. There are probably about ten or so in California right now. And battery electric vehicles are a very important part of it. But there’s some real issues with battery electric vehicles, whether they really will be fully accepted: there’s the range issue, the cost of batteries, so there’s a lot of people that believe that hydrogen fuel cell vehicles will ultimately be at least, if not more, important and dominant than battery electric vehicles.

GELLERMAN: Now, back in the 1990s, California did mandate that carmakers produce a certain amount of zero emissions fuel vehicles, and - well, let's be generous - that didn't work the way you had hoped.

SPERLING: That is being generous.

GELLERMAN: (Laughs.)

SPERLING: But this is the same policy, the same rule. And it did start in 1990. It turned out that the technology didn’t advance as fast as we thought, that batteries were more expensive than we anticipated they would be, the improvements were slower than we anticipated, and so, frankly, it did become a problem. The good news is that now, thanks in part to, you know - one of the benefits, one of the impacts of that zero emission vehicle program over the years is - it did motivate the car companies to really focus on electric vehicle technologies.

And even though it wasn’t successful in getting a lot of vehicles out there - they did invest a lot in developing the technology. And it is what spurred Toyota to start with the Prius and the hybrid vehicles. And so, it’s all part of the same path and now with Nissan and General Motors making major commitments to electric vehicles, and with all the other car companies all ready to launch electric vehicles - we’re on that path now.

GELLERMAN: Could one of the reasons that these car makers are behind this be because the average cost of a car is going to go up almost $2,000 and that they’re going to come out, well, flush?

SPERLING: There certainly has been a dramatic turn-around in the attitude of the automobile industry in the last few years. They see that this is inevitable, that there is a problem with oil, and even more important, there is a problem with climate change.

You know, I’m on leave now in Washington DC, and I’m hanging out here - and I see how the politics have been poisoned here about climate change, you can't even talk about climate change, but that doesn’t reflect reality in industry or in a lot of other places.

The car industry, across the board, is fully acknowledging and accepting that climate change is real and something has to be done about it - that they can make the vehicles much more efficient, and that we’re moving toward electric drive technology with batteries and fuel cells. So I think there’s now a full acknowledgement that this is necessary, this is going to happen. And instead of fighting it, they have a lot more to gain by being part of the solution than part of the problem.

GELLERMAN: Yeah, we should say, though, that if you have an electric car, and you’re generating that electric energy by burning coal, that’s not a zero emissions car, it’s just not coming out of the tailpipe, it’s coming out of the smokestack.

SPERLING: Absolutely. And so part of this pathway toward electric drive vehicles is making sure that the electricity grid is cleaned up as well. And in the United States on average, about half of the electricity is coming from coal but that percentage is coming down. And there are almost probably, I think, three quarters of the states in the U.S. already have programs to introduce more renewable energy. In California the requirement is that 33 percent of the electricity must be renewable electricity by 2020 and most of the rest is nuclear and natural gas. So the emissions are very low in California, and they’re coming down everywhere.

The Nissan Leaf. (Photo: Wikipedia Creative Commons, Tennen-Gas)

GELLERMAN: As I understand the California decision - if I am in Massachusetts and I buy one of these vehicles, it counts towards California’s goal.

SPERLING: That’s a very good point. So that when we say the California program, it’s really California and ten other states - ten other states have agreed to adopt whatever California adopts. And so what we are launching here is a revolution, and ideally, hopefully, the federal government will gradually come to embrace these same requirements, but even if they don’t we’re going to see all of the car companies introducing this technology, not just in those ten states, but across the country.

GELLERMAN: What about me? How am I going to fare in terms of my pocket book in these rules and standards?

SPERLING: Well, in the end, consumers should come out ahead. In fact, in some of these rules, they come out ahead immediately. With the vehicle rules, the cost analyses that we’ve done suggest that by 2025, the average vehicle will cost about $2,000 more than today but they will be so much efficient that over that time, they will save $6,000 in reduced fuel costs from here to there. And so the result of that is that the average consumer comes out ahead. And because the average consumer also takes out a loan on their car, for instance a five-year loan, from day one, you will be saving money on your car because the increase in your car payment will be less than the amount of fuel savings that you get.

GELLERMAN: Daniel Sperling is director of Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California Davis and a member of the California Air Resources Board. Professor Sperling, thank you so very much!

SPERLING: It's a pleasure.

Related links:

- The California Air Resources Board

- Daniel Sperling

Cellulosic Fuel Update

Bluefire Renewables plant site. Cellulosic companies have struggled to secure funding to build commercial capacity plants. The recession didn’t help.

GELLERMAN: Well, back in 2007 then-President George W. Bush promised federal funds to find new fuels for our cars.

BUSH: One of these days, the scientists tell me, and I believe, that we will be able to manufacture fuel for your automobiles from switch grass, or biomass, or wood chips. And then all of a sudden if you really think about it and are optimistic about America’s capacity to use technology to change our way of life, then all of a sudden you begin to see the rationale for saying we can reduce gasoline usage by twenty percent over the next ten years. I believe it's coming. I really do.

GELLERMAN: And since 2007, the federal government has devoted hundreds of millions of dollars in subsidies and loan guarantees for companies hoping to make fuels from plants - but so far progress is stalled. Jeremy Martin is a biofuels expert with the Union of Concerned Scientists.

MARTIN: The promise was to start producing commercially as early as in 2010 at a level of 100 million gallons, and then going up steadily to this level of 16 billion in 2022. And what’s happened is that that first production hasn’t happened yet. The facilities which were - didn’t get built and a lot of that has to do with what happened in 2008 and 2009, and I’m sure everybody will remember that those were tough years to get a loan for just about anything and, in particular, for new technology.

GELLERMAN: But back in the Bush administration in 2007, the government awarded $385 million dollars in grants to jumpstart ethanol from woodchips and switch grass, citrus peel…

MARTIN: Yeah, and also agricultural waste – things like corncobs and corn stalks and even garbage. But I would say they announced that level of grants, actually if you went through the records you’d find that the majority of those checks never got cashed or even mailed out. Those grants required the companies to raise a lot of private capital to match government money, which probably seemed reasonable in 2007. But of course, 2008 and 2009 were very tough years to borrow money under any circumstances.

GELLERMAN: Well, one of the companies that did cash the federal checks was Range Fuels in Georgia. They actually built a plant. What happened to them? They got over 160 million dollars in loan guarantees and in grants and in money from the state.

MARTIN: Yeah, they are the one exception. They moved very quickly and got started. So there are a lot of different ways that people have to convert this cellulosic biomass into fuel. And you know, they were using an existing technology that just wasn’t cost competitive. Unfortunately, we learned the hard lesson first and the other technologies are still, you know, at the starting gate.

GELLERMAN: So, is this an example of the federal government trying to pick arenewable energy technology winner and having a failure? Because, as I understand it, they haven’t produced a drop of cellulosic ethanol.

MARTIN: I think we’re certainly behind schedule. As far as picking winners, I mean there was an important reason that people wanted an alternative to oil and that was climate change, it was oil dependence, high oil prices. And I think all of those reasons remain just as true today as they were in 2007. So that’s why, I think, it’s worth taking the time and sticking with this one because we do need alternatives to oil.

GELLERMAN: Well, the backer of that plant in Georgia actually has a new company in Michigan. And I’m looking at an article that he had to, you know, tell potential investors what the risks were. And this is a direct quote: ‘We have a limited operating history, a history of losses, and the expectation of continuing losses, and we have no experience in the markets in which we intend to operate.’ Boy, that sounds pretty risky!

MARTIN: Vinod Khosla, I think, is the investor you’re referring to.

GELLERMAN: Yes, he was the one that did Range Fuels and this one.

MARTIN: Yeah. Generally these start-up companies have a variety of backers. He’s backed a number of these new technologies, and I think his approach is to look for a lot of things and hope some of them pan out. And you know, the first bet here hasn’t paid off and he lost a good bit of money on that but he’s still bullish that there’s a market here in the future. And I remain convinced that it’s worth focusing on and that it’s worth investing in.

GELLERMAN: Well, cellulosic ethanol promises to be a lot cleaner than gasoline, I guess something like 85 percent in terms of greenhouse gasses?

MARTIN: Yeah, that’s exactly right. And there aren’t a lot of other alternatives that are that clean. And when you look at the scale of the problem, how much gasoline we use, the technology that allows us to turn environmentally friendly sources of biomass into fuel, it’s a really important technology and one that’s worth investing in.

GELLERMAN: So, is the challenge right now technological? Is that the problem?

MARTIN: Well, there’s certainly technological challenges, and a variety of different approaches, and a number of companies with new technologies. Some of them use heat and gas to convert the biomass into gasses, and through what they call a thermo-chemical process that they use to make fuel, others use enzymes.

GELLERMAN: Those are things, chemicals that speed up processes.

MARTIN: Yeah, or organisms, microorganisms. So there’s a variety of different technologies, and the technologies certainly is one of the challenges. But the financing of these facilities has proven to be one of the really significant challenges. And I think that’s one where the circumstances that weren’t foreseen in 2007 really have slowed things down.

GELLERMAN: The technology or the idea of getting energy out of this material is not new. It goes back to 1898!

MARTIN: Yeah, absolutely! And people have done it on occasion. The question is making it cost-effective. I think it’s long been recognized that if you could make biomass into fuel, you could have a great business.

GELLERMAN: But didn't Chevron Oil and Shell, didn't they have investments in cellulosic companies? What happened to their investments? What happened to those companies?

MARTIN: Well, a lot of those major oil companies are investors in many of the cellulosic companies. I’m looking forward to seeing them produce fuel instead of just press releases. But you know, they’re the ones who control the fuel market, and, essentially these laws that Congress has passed, amount to encouragement to them, or a requirement, that they clean up their act and start producing cleaner fuels. The technology will march forward with or without government support, but how long it takes to really start to displace oil and to really start to reduce these emissions is what’s at stake here.

GELLERMAN: Well, Jeremy Martin, thanks so much.

MARTIN: My pleasure, thank you.

GELLERMAN: Jeremy Martin is a biofuels expert and senior scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Related links:

- Advanced Biofuels Association

- American Council on Renewable Energy

- Renewable Fuels Association

[MUSIC: Rory Gallagher “For The Last Time” from Rory Gallagher (Eagle Rock Entertainment 2010 Reissue)]

GELLERMAN: Just ahead, curbing herbicide use near highways. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Nicole Mitchell: “Thanking The Universe” from Black Unstoppable (Delmark Records 2007)]

GELLERMAN: It’s a recycled edition of Living on Earth, I'm Bruce Gellerman. Coming up: three recent studies raise new concerns about industrial chemicals and human health. But first, this Note on Emerging Science from Stephanie McPherson.

Science Note/Bat Aerodynamics

Big eared townsend bat (Corynorhinus townsendii). (Photo: PD-USGov)

[BAT NOISES]

MCPHERSON: Bats flit across the night sky in a rapid ballet of twists and turns. Now, researchers believe the bats agility is due to the tiny hairs on their wings.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME MUSIC]

MCPHERSON: The hairs on bats’ wings bend in the breeze and trigger super-sensitive cells that help them register the speed and direction of the wind.

Scientists from the University of Maryland measured electrical firings from the bats’ brains as they responded to the signals coming from the sensor cells. The brains were most active when they sensed the wind coming from behind – a situation that could lead to stalling.

The researchers wanted to know how the bats put those signals to use. The mammals flew through obstacle courses - first with their hairs intact, then again after the hairs were removed using a topical cream.

The bats moved easily through the course during the first round. But when their wings were hairless, the bats flew faster and took wider turns. Since the hairs weren’t there to trigger the sensor cells, scientists believe the bats sped up to avoid dropping from the sky – in the real world, they would’ve had trouble catching prey or avoiding predators.

Researchers are looking into how they can use this information to improve wind sensors on airplanes. Perhaps they can prevent stalling with a wing and a hair. That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science, I’m Stephanie McPherson.

Related link:

Bat hair research at the Institute for Systems Research, University of Maryland

Chemicals and Health

Perfluorinated chemicals are the basis for Teflon products, which render surfaces nonsticky.

GELLERMAN: It’s taken nearly a quarter of a century but the EPA has finally concluded that the chemical perchloroethylene - is a likely human carcinogen. You know Perc - at least by the smell - it’s used by many dry cleaners; but now the EPA says it will largely phase out the cancer-causing solvent.

Perc is just one of more than 62 thousand industrial chemicals that were presumed safe back in 1976. That's when the federal government first began regulating these compounds, but still today, most have never been investigated for health effects - they were grandfathered in.

Now three new studies suggest some of these chemicals, even measured in parts per billion - can have far reaching health effects - and Dr. Richard Denison of the Environmental Defense Fund says there's no avoiding them.

DENISON: The amounts are really staggering and they've grown dramatically over the last few decades. One estimate puts it at 27 trillion pounds per year in the U.S. That's the equivalent of 250 pounds per person every day.

GELLERMAN: Well, in your recent blog you write about three recent studies that raise concerns about some of these chemicals. Let's go through these studies, okay?

DENISON: Sure. They are among a group of studies that are looking directly at effects in people. Most of the data we've relied on in the past has been data derived from laboratory animal studies. But increasingly the field of epidemiology is finding that linkages directly to people can be established between chemical exposures and certain types of health effects. And these are three studies that do just that.

GELLERMAN: The first one has to do with something called PCE, or I guess some people know it as Perc. It's used as a solvent in dry cleaning, degreasing, spot removers, that kind of thing, right?

DENISON: That's right. It's also got a lot of industrial uses for cleaning metal parts and so forth.

GELLERMAN: The study that you cite was done recently by Boston University researchers.

DENISON: They looked at a large group of people, some 800 people that had reported some level of exposure to this chemical, either while they were in the womb, in other words, their mother was exposed, or in their early childhood. And this was the result of contamination of drinking water in the areas in which these 800 people lived.

GELLERMAN: So what did they find? What did the researchers find?

DENISON: Well, they compared this group of 800 people to a group of unexposed individuals and asked the question, how likely was it that these individuals who had been exposed early in life, later in life would engage in so-called "risky behaviors." So this included drug use, smoking, heavy drinking. And what they found was a much higher incidence, some 50 to 60 percent of an increase in the extent of these risky behaviors was observed in the individuals who had been exposed early in life to this solvent compared to those who had not.

GELLERMAN: Can you make the association between something that happens in the womb and behavior so much later in life?

DENISON: Well, there is a lot of additional information that suggests that solvents like PCE are able to do just that. An early life exposure leads to impairment of cognitive abilities, changes in mental disposition and behavior. And what's unique about this study is both the scale of it, the large number of people that were tracked, but also the manifestation of those mental/behavioral changes in directly measurable activities such as drinking and drug use.

GELLERMAN: Of course, there are people who abuse drugs who might never have had exposure to this chemical.

DENISON: This is one of the difficulties in doing human studies. Many effects that we look at have multiple causes, and it's very difficult to ever definitively say that a particular cause is responsible for the entire incidence of a particular outcome. So rather what we're looking for are correlations and in this case the researchers went to significant steps to control for other factors that could potentially confound the results. So it really does look in this study like the strongest correlation is between this early life exposure to a toxic solvent and tying that in this case to a much higher likelihood of developing those risky behaviors later in life.

GELLERMAN: Let's talk about the second study. It took place in New York City, at Mount Sinai. It has to do with something called phthalates. What are phthalates?

DENISON: Phthalates are a group of chemicals that are used widely in commerce today. They're used in everything from cosmetics, to certain types of cleaning products, to a variety of different plastics.

GELLERMAN: So the researchers in New York, they found that there was a relationship between this chemical and overweight kids?

DENISON: That's right. What the researchers studied was a group of about 400 black and Hispanic kids in New York City. They measured several ways in which these children were overweight and they correlated that with the concentrations of these chemicals in the bodies of these children. And they found a very strong relationship. The higher the levels of these chemicals, the more likely they were to be obese at ages six to eight years old.

GELLERMAN: What about things like poor diet, or the kids not getting enough exercise, wouldn't you look at those as variables?

DENISON: Obviously, diet and lifestyle, exercise levels, all affect this. What increasingly the science is pointing to, however, is that early life exposures to certain chemicals can predispose people to being obese later in life. These are chemicals that we know are similar to hormones that are naturally present in the body and they can interfere with the effects of those hormones even at very low doses. They can affect both early development in males and females.

GELLERMAN: The third study you write about are called perfluorinated chemicals. What are those?

DENISON: These are chemicals that are probably known to most people because of their uses in products like the Teflon brand of products and the Scotchgard brand of products. Typically, they're used as coatings on paper packaging, on textiles, to impart water-resistance or grease-resistance. These chemicals are very persistent in the environment, and in some cases they can build up in our bodies.

And this study looked in particular at a group of these chemicals in a very large group of kids that were immunized early in life for diphtheria and other diseases. So then the authors looked for a correlation between the levels of these chemicals and the levels of antibodies that were produced by vaccinations these children had received years earlier. And what they found was that the higher the levels of these chemicals in the bodies of these kids, ages five to seven years old, the lower the levels of antibodies to these two vaccines. So that means that there's at least a potential here that these chemicals are interfering with the effectiveness of those vaccines even years after the initial exposure.

GELLERMAN: Then wouldn't we expect that as they grew older, they might be more susceptible to diseases and the things the vaccines were supposed to prevent?

DENISON: That is certainly the implication. It needs, certainly, further follow-up, but it does suggest that when we are exposed to things early in our lives, that they have some profound effects on our immune system, our mental capacity, our ability to regulate our weight. These kinds of fundamental processes in the human body seem to be being affected by early life exposures.

GELLERMAN: So let me ask you, Dr. Denison; you say we have 27 trillion pounds of these, can we be, you know, effectively protected, or can these chemicals be effectively regulated?

DENISON: Unfortunately, the answer to that question is no. We have a very obsolete chemical safety law that hasn't been amended for 36 years. So we need to update this law, it's called the Toxic Substances Control Act, and it needs to reflect the most recent and best science that's available to us. I think there are, on the margins, certain things that can be done to reduce one's exposure, but I think in the long run it's both unfair and impractical to put the burden on individual consumers to try to figure out where these chemicals are and to try to avoid them. And it's probably a perfect example of where we really need a national solution that makes sure that these chemicals are fully tested before they get into the marketplace so that people, individuals, don't have to worry about themselves and their families.

GELLERMAN: Well, Dr. Denison, thanks a lot.

DENISON: Thank you, Bruce. It's a pleasure to be on your show.

GELLERMAN: Richard Denison is a senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund.

Related links:

- Richard Denison’s blog post, “Linking Everyday Chemicals to Disease” with links to summaries of studies

- Environmental Defense Fund’s Chemicals and Nanomaterials Blog

[MUSIC: Savoy brown “Is That So” from Raw Sienna (Decca Records 1970)]

Bare Shoulders: Herbicide Along the Highway

(Lisa Arkin)

GELLERMAN: Along the sides of the nation’s highways are strips of space; some covered in grass, trees and flowers, others stripped bare. And as Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet reports, it’s these areas that cause concern for some who travel the roads.

[HIGHWAY SOUND]

LOBET: Lisa Arkin pilots her Subaru wagon along a highway outside Eugene, Oregon. She gazes at the road shoulder and shakes her head.

ARKIN: We just passed over the Willamette River and you can see acres and acres of dead vegetation, dead from herbicide spray.

LOBET: Arkin is executive director of Beyond Toxics, a non-profit that’s been trying to persuade the state of Oregon to find other ways of maintaining the highways.

ARKIN: When they spray, people with immune deficiencies, someone going through a cancer treatment, someone with allergies or asthma - you might have children in the car, you might be a pregnant woman, and you have no idea that you have driven through miles of a recent spray.

LOBET: Arkin’s disagreement is with the state, not with this county. Unlike the state, Lane County has a no-spray policy. And the contrast between state roads and county roads is plain to see.

In contrast to the state as a whole, Lane County, Oregon has a no-spray road policy.(Lisa Arkin)

ARKIN: And now, we are merging onto a highway that’s managed by the Lane County public works department and we start to see–flowers! And vegetation that is still green.

LOBET: Opposition to herbicides is not uncommon here in Lane County, home to Eugene, a university town. It’s a part of Oregon where organic agriculture is strong. Last spring, when the Oregon Transportation Commission heard testimony about roadside herbicide policy, farmer John Sundquist spoke up.

SUNDQUIST: I have testified before you several times in the past urging you to protect citizens and the environment by stopping the poisoning of state-maintained roads in Lane County. And I asked you to enjoy the green, beautiful, poison-free, salmon and wildlife-enhancing roadsides of Lane County.

LOBET: The State of Oregon and its Department of Transportation is much like other state DOTs. It sprays herbicides, such as glyphosate, that disrupt plant metabolism. That can be once or several times a year. Will Lackey coordinates the teams that work in that space to the right of the white line in Oregon, and he describes how it should look.

LACKEY: We really would not like to have any vegetation growing six to eight feet from the pavement. That is primarily for drainage, for a safe recovery zone for cars so they have a safe place to pull off, visibility, fire hazards–and it’s also–if we can keep it bare, that is our first line of defense for noxious weed control.

LOBET: Two of the main questions that preoccupy highway workers when they contemplate any stretch of shoulder are: is it free of plants, in general? And specifically, are there any noxious or invasive plants like rush skeletonweed or puncture vine?

LACKEY: We target a lot of just noxious weed control. So we have people out on four-wheelers or even just backpack spraying, just going after individual plants.

LOBET: Washington State, Oregon’s neighbor to the north, also uses herbicide but has dramatically reduced the amount in recent years. Ray Willard manages roadside maintenance in Washington State. He’s a landscape architect by training. He says when his department first scrutinized its use of herbicide, it found some was unnecessary.

WILLARD: I think what was happening at that time is a lot of the decisions that were being made, were being made by the crews out in the field, and so there really wasn’t as much oversight in terms of: ‘Is this really the right thing to do? Is it necessary or is there a more effective way to do it?’

Oregon Highway 36, maintained by the state, is routinely sprayed with herbicide. (Photo: Lisa Arkin)

LOBET: As Willard’s department reevaluated, it found there wasn’t much research to help predict what would happen if they sharply reduced herbicide use. Would they need much more staffing? Would it cost much more? They set clearer guidelines and instituted annual training for highway workers, and Washington cut its herbicide use by 66 percent, from 126 thousand pounds of active ingredient in 2003 to 42 thousand. Last year, they actually used more than the year before. Willard says that’s because they’ve gone back to spraying some stretches.

A different section of the same Oregon Highway 36 where herbicide is not permitted

(Lisa Arkin)

WILLARD: What we found was that it is actually, in a lot of cases, cheapest to treat that band of earth with herbicides. And so, as a result, some of the areas that we had let go and grow back to grass now, we are maintaining them as vegetation-free again now with herbicides.

LOBET: He points out some plants when they’re cut come back stronger each year.

WILLARD: If we can make very precise, specific applications we can do that very safely in terms of worker exposure and environmental exposure and we are much more efficient and effective in terms of our budget and use of the taxpayers’ money.

LOBET: But those who oppose this method of keeping the roadside clean and bare say taxpayer money also goes to uncalculated health costs. The public health effects of herbicides is an area of research that’s still developing. People are unlikely to be severely poisoned. But the jury is still out on more subtle effects to developing fetuses or people with genetic predisposition to greater sensitivity. The concern over herbicides was enough to persuade Oregon’s former Transportation Commission Chair Gail Achterman to send a message last year that the status quo is not acceptable.

ACHTERMAN: I am very worried about this issue. I don’t think it’s good for our employees nor do I think it is good for society to be using herbicides when other alternatives are available. We are going to start running into real liability exposure on the continued use of these toxics.

LOBET: That message was heard. Oregon Vegetation Management Chief Will Lackey says change is happening.

LACKEY: Over the next five years we are going to reduce our pounds of active ingredient by 25 percent. So our bare shoulders, our brush treating and some of our landscape – we are going to reduce our pounds of active ingredient by 25 percent.

LOBET: There have been similar public rebellions against highway herbicide over the last 30 years in other parts of the West, Northeast and in Minnesota, and the trend is toward reduction in those regions. The issue is, so far, not an issue in much of the Midwest and the South.

LOBET: For Living On Earth, I’m Ingrid Lobet.

Related links:

- Washington State Vegetation Management Program

- Beyond Toxics

- National Roadside Vegetation Management Association

[MUSIC: Taj Mahal “Ain’t Gwine To Whistle Dixie (Any Mo)” from The Real Thing (Sony Music 1971)]

GELLERMAN: Coming up, Captain Henry Hudson had it hard---his crew mutinied and he was cast adrift. Today, Arctic explorers have it easier, but not by much. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from The Grantham Foundation: for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and Gilman Ordway, for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is Living on Earth, on PRI, Public Radio International.

CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jazz Soul Seven: “People Get Ready” from Impressions Of Curtis Mayfield (BFM Jazz 1012)

GELLERMN: It's a recycled edition of Living on Earth, I'm Bruce Gellerman.

BirdNote® What Do Birds Smell?

The Turkey Vulture has a keen sense of smell. (Photo: Jerry Kirkhart)

[BIRD NOTE® THEME]

GELLERMAN: They may be small and flighty - but don’t call them bird brains. Birds have mighty keen senses----and BirdNote®’s Michael Stein has a nose for a good story.

STEIN: Birds are justly renowned for their highly sensitive eyesight and hearing. Consider the exquisitely keen eye of the eagle, [Bald Eagle call] or the unerringly acute ear of the owl [A brief bit of Great Horned Owl calling]. But what about birds’ sense of smell? Among the many birds of the world, some are, without doubt, prodigious smellers.

[Ocean waves]

Diminutive seabirds called storm-petrels are olfactory savants – they can detect the scent of prey from a distance of 25 kilometers! The kiwis of New Zealand sniff the ground for earthworms

[Sniffing sound]

Before probing deeply to intercept their wiggly prey. Turkey Vultures also have a supremely keen sense of smell to lead them upwind from great distances to their malodorous feasts. Songbirds were long thought to have a poor sense of smell, because the olfactory center in their brains is proportionally tiny. However, current research suggests that some songbirds may use smell to find food, select prime nest material, and even help navigate across vast regions.

[Gray Catbird]

Experiments in the US with migratory Gray Catbirds show that, for adult birds repeating a migration route, sense of smell is more important than either orientation using the sun or using the earth’s magnetic field. It may well be that many songbirds “smell” their way back to last year’s nesting site. [Brief bit of Gray Catbird. I’m Michael Stein.

GELLERMAN: To see photos of some champion avian sniffers, follow your nose to our website at LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Bald Eagle call recorded by J. R. Storm. Great Horned Owl duet recorded by W.R. Fish. Fox Sparrow song by L.J. Peyton. Gray Catbird song recorded by G.F. Budney. Gray Catbird call recorded by W.L. Hershberger. Brown Kiwi calls recorded and provided by Martyn Stewart, naturesound.org

- BirdNote® What Do Birds Smell? was written by Bob Sundstrom.

[MUSIC: Fareed Haque “Almost Cut My Hair” from Déjà Vu (Blue Note Records 2009)]

Arctic Explorers

Arctic Sea Ice. (Courtesy of Fiamma Straneo)

GELLERMAN: Four hundred years ago explorer Henry Hudson set sail from England in search of an Arctic route to the riches of Asia. It was an ill-fated journey that ended in disaster for Captain Hudson and his son - and they never did discover the fabled Northwest Passage. Even today, despite satellite maps and GPS, much of that same region in Northern Canada, remains an unexplored mystery. But still, there are those who dare to venture –and challenge the unforgiving place just as Henry Hudson did 4 centuries ago. Emily Corwin of Mind Open Media has their story.

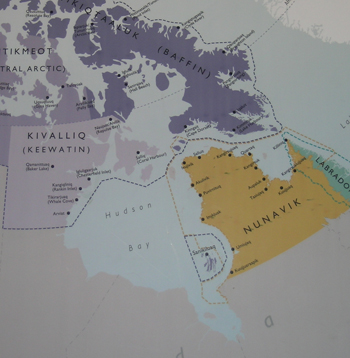

An Inuit map of Hudson Bay.

Credit: Courtesy of Fiamma Straneo

MILLMAN: My name is Lawrence Millman, and I'm an arctic explorer, and I have an abiding interest in other arctic explorers who disappeared off the face of the earth.

[MUSIC: Zorn1.]

CORWIN: On a modern-day expedition to the Hudson Bay, Larry Millman overheard an unusual story about the first white man to live among that region’s native Cree. The story had been passed down among the Cree for generations, and the white man was known as Firebeard.

MILLMAN: With very little research I determined that in all probability Firebeard was Henry Hudson, who was perhaps the best-recognized navigator of his day.

CORWIN: There are only a few things we know about Henry Hudson’s personal life.

MILLMAN: Here’s one of the things we know about Henry Hudson, that he had a great affection for bangles. Like jewelry - and males wore, in those days, lots of jewelry like bracelets - he liked golden wristbands, and rings. We know that and there's one source that mentions that he really enjoyed big meals.

CORWIN: Back in the early 1600s, navigators were tired of sailing down around South America, all the way across the Pacific to Asia. So a British trading company hired Henry Hudson to find a shorter route.

(Courtesy of Fiamma Straneo)

MILLMAN: He sets out from England in 1610.

[MUSIC: MEKUBOLIM Zorn2]

MILLMAN: Touches Iceland, gets some supplies and heads into the 'furious overfall' otherwise known as Hudson Strait. They thought, because of all these heavy currents, that it was close to the Pacific, it had to be a great ocean. No, it wasn't a great ocean, it was a long narrow strait.

CORWIN: This so-called 'furious overfall' with its counter-clockwise swirling chunks of ice was much, much colder than the guys on Hudson’s crew ever expected. Pretty soon their ship got stuck– it was mired in the ice.

MILLMAN: There's a feeling of complete and utter paralysis. You might like to go somewhere but you can’t go anywhere, you can't get your boat to move a bloody inch.

CORWIN: Hudson’s crew wanted to turn around. They said:

MILLMAN: 'As soon as we get out of this ice, Captain Hudson, we're heading home.' There was an interesting democracy among crews of that day. If the crew wanted to head home and the captain didn't, the crew got their way. He said ‘well look', he brought out a map, he showed his crew the map, 'we're a hundred miles farther West than any other known expedition. And you want to turn around.’

(Courtesy of Fiamma Straneo)

[MUSIC MEKUBOLIM ZORN3]

MILLMAN: Well they couldn't turn around and he was using that possibly as part of his ammunition.

[CLIP FROM FILM: We stand now on the edge of discovery. This great bay must open somewhere and yield a passage. Let us thrust westward in the common triumph of raising the Indies!]

CORWIN: That’s from the 1964 film “The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson.” Come November, it was too cold and icy to go on. Hudson and his crew would spend the winter camped on the shore of the frigid James Bay.

MILLMAN: It was just an absolute miracle that they survived the winter.

CORWIN: The crew was starving and it was freezing cold. Scurvy made their gums bleed and their teeth loose. When the ship could finally sail again, Hudson told his crew they would return to England. But there was a problem.

MILLMAN: Hudson wasn't going in the right direction for England. He was heading west, and he should have been heading north, up along the coast and out the same way they came in. And when one of the members of the crew noticed that certain individuals had cheese, and had more food than they themselves had— that was the spark that inspired the mutiny.

[CLIP FROM FILM: Arrh - now that you’re free of us master Hudson, you may sail westward for all you are worth! Hudson: Mr. Green– it is not too late. Reconsider!]

CORWIN: The crew threw Hudson and his son on a sailboat, and headed right back to England. Did Hudson go by “Firebeard” and live among the Cree, or did he freeze to death alone in the bay? We don’t know. 400 years later, another adventurous Arctic Explorer wanted her turn. The legend of Henry Hudson loomed.

STRANEO: Every time I brought up Hudson Strait everybody shook their head, it had this reputation for being a really tough place where to work.

Fiamma Straneo is an ocean scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts.(Courtesy of Fiamma Straneo)

CORWIN: That’s Fiamma Straneo. She’s an ocean scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Three years in a row Straneo has returned to the same place where Henry Hudson disappeared. She’s not looking for riches or spices or any of that. And none of her crews have ever threatened mutiny. See, Straneo is on a new kind of mission. She wants to understand climate change in the Arctic.

[MUSIC: Exilio Zorn5.]

STRANEO: And so if we think of Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait as a small microcosm in the climate system, then if I can understand how they work, if I know what goes in and I know what comes out, then I can put this in a bigger model that has the entire planet, the entire atmosphere, and its going to help us predict future change.

CORWIN: As the planet heats up, moisture evaporates from warm places like the tropics. And then wind pulls that moist air over the arctic, where it rains and snows into the ocean. That fresh water is lighter than the saltwater, so it sits like a blanket on top of the entire ocean, getting in the way of the ocean’s usual temperature regulation and circulation patterns. Straneo is monitoring the water in the Hudson Strait, a bottleneck that connects the Hudson Bay to the Atlantic Ocean. This is the strait that Henry Hudson may have called the 'furious overfall' - with its massive 30-foot tides and swirling currents.

STRANEO: When you’re close to land you just see the entire landscape change. You know, your ship just goes up and down and you look and you thought oh there was an island there - well its gone. Because there are these super strong tides, the other thing that you see are these really fast currents, which switch every six hours or so and there’s so much mixing and turbulence the water literally boils.

CORWIN: Here is Straneo, in the same treacherous strait that brought about Henry Hudson’s demise 400 years ago.

STRANEO: And so if you read the old books and the old maps, Hudson Strait is actually indicated with a waterfall like the currents were so strong that ships had a really hard time navigating it.

MILLMAN: There are a couple maps that actually show Hudson bay long before Europeans ever went there. "Here Be Dragons, Here Be Monsters, or you fall off the edge at this point."

Lawrence Millman is a modern day Arctic explorer.

CORWIN: The legends of monsters that tormented Henry Hudson’s crew boded ill for Straneo’s expedition. Yet Straneo forged ahead. For her research, she put three chains of instruments down into the water. These chains – called moorings - are so big they have to be lowered in with a crane. What looks like a massive red fishing bobber sits at the top, while the instruments sink down, measuring water salinity, velocity, and temperature.

STRANEO: I think the most exciting moment was putting everything in the water the first time. Just seeing everything disappear, it feels silly because that's it! You've just chucked thousands - hundreds of thousands of dollars in the water, don't know what they're doing, but just putting everything in and know that if everything goes as planned you can come back and there will be data, and there's something magical about letting go of all the instruments and just sort of walking away and trusting.

CORWIN: Straneo’s reward for taking on this challenge - is getting to be the first.

STRANEO: One of the reasons to work in the arctic is that it's an incredibly important place in the circulation of the ocean and the climate system and yet we know so little about it, and so you can go to so many places in the arctic and be the first person ever making measurements there, and so when you pull up this instrument that's been in the water for an hour, or for a year, and you look at these data, you think WOW, nobody's ever seen what's going on under the surface of the ocean here, you're sort of, hearing a story for the first time.

Chart of Hudson Bay (Courtesy of Fiamma Straneo.)

CORWIN: Kind of like when Larry Millman heard the story of Firebeard for the first time. For Millman, being in a place like the Hudson Bay gave him something else, too– a new kind of sensory experience.

MILLMAN: When you're in a place that you know, each wrong step will land you in if not trouble, deep doo doo, bear, caribou, or otherwise, then you're aware of the world around you. So I enjoy that all my senses are on the alert when I’m traveling in the Arctic.

CORWIN: Larry Millman left the arctic with a new kind of awareness and a story about Henry Hudson. Henry Hudson’s mutinous crew left Henry in the middle of the Hudson Strait. And Straneo left the Hudson Strait with the data she needed to build a predictive model of climate change in the Arctic. All of them did something that had never been done before, in a place no one – except for, perhaps, the native Cree – was meant to survive.

For Living on Earth, I’m Emily Corwin.

Related links:

- Mind Open Media

- Watch “The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson” (28 min.)

- Lawrence Millman’s website

- Fiamma Straneo’s Research Group

[MUSIC: Fareed Haque “Almost Cut My Hair” from Déjà Vu (Blue Note Records 2009)]

GELLERMAN: Our story about arctic explorers comes to us from Mind Open Media, working with researchers to tell stories about their science and their lives. To learn more, head to our website, LOE dot org.

[SEAFARING SONG CONTINUES.]

Earth Ear

A storm petrel. (Photo: Cotinis)

[SEABIRDS: Lang Elliot “Petrel Night” from Seabird Islands (Nature Sound Studio 1996)]

GELLERMAN: We leave you this week among Seabirds.

[SEABIRD SOUNDS]

GELLERMAN: Thousands of Leach’s Storm-Petrels circle overhead, swooping and calling into the night. Lang Elliott captured these sounds for his CD he calls “Petrel Night.”

[SEABIRD SOUNDS]

GELLERMAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Jessican Ilyse Kurn, Ingrid Lobet, Ike Sriskandarajah and Jeff Young, with help from Gabriela Romanow, and Sammy Sousa. Our interns are Annabelle Ford, Christy Perera and Annie Sneed. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE dot org – and don’t forget our Facebook page! It’s PRI’s Living on Earth. Steve Curwood is our executive producer. I'm Bruce Gellerman. Thanks for listening!

PRI ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield Farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at justeatorganic.com. Support also comes from you, our listeners, the Go Forward Fund, and PaxWorld Mutual and Exchange Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social and governance factors into investment analysis and decision-making. On the web at paxworld.com. Pax world: for tomorrow.

PRI ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth