September 22, 2017

Air Date: September 22, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The US Military & Climate Disruption

View the page for this story

Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and especially Maria all have one thing in common — the US military is in the front lines of response. Members of the National Guard, Navy, Air Force and Coast Guard are among many emergency responders mobilized immediately to help after such disasters. As retired Rear Admiral David Titley tells host Steve Curwood, though President Trump seems to discount the risk of climate change, the Department of Defense is focused on understanding and preparing for continued climate disruption and the security threats it poses in a warming world. (12:18)

Climate Week 2017

View the page for this story

Against a backdrop of massive hurricanes that caused devastation in the Caribbean and the south eastern US, as well as destructive floods in Asia, diplomats, business, state and local leaders, advocates and climate thinkers of all kinds gathered at alongside the opening session of the UN General Assembly in UN New York for Climate Week 2017. Alden Meyer from the Union of Concerned Scientists discusses with host Steve Curwood how these leaders reacted to the extreme weather events, and plan to further fight climate disruption. (10:39)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Amid the dismal news of destructive hurricanes and floods, Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood manage to find some positive environmental news beyond the headlines to discuss. This week, they look at proposed marine sanctuaries in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and remember a remarkable example of environmental cooperation among nations. Less encouraging is news extreme weather events seem to do little to influence public opinion about global warming. (04:07)

BirdNote®: Roosting Tree Swallows

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

On September 22 Fall arrived in the Northern Hemisphere, and millions of singing Tree Swallows will soon fly south. But for now, explains BirdNote’s Mary McCann, these summer performers are staging their final shows of the season. (02:10)

Science Note: The World’s Most Common Language, It Seems

/ Noble IngramView the page for this story

Breaking language barriers can be difficult for even the most talkative humans. But as Living on Earth’s Noble Ingram reports, a new study from the Netherlands Institute of Ecology has found that trillions of microorganisms communicate effectively through scent signals - all without making a sound. (01:48)

Big Chicken

View the page for this story

Before science knew much about drug resistant microbes, farmers routinely used antibiotics to plump up livestock such as chickens for market. Author Maryn McKenna traces how this history of antibiotic use shaped agriculture into today’s mostly industrialized market. Maryn McKenna joined host Steve Curwood to discuss the issues, and changes underway in poultry factory farming today. (15:52)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: David Titley, Alden Meyer, Maryn McKenna

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann, Noble Ingram

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

The White House may oppose effective climate action, but when global warming aggravates triple hurricane disasters in America, the military must take action.

TITLEY: The Department of Defense is very effective at being some of the first people on scene. This is a team sport, this is interagency, it's not just the military but what the military can certainly provide is communications, logistics, helicopters.

CURWOOD: Also, as diplomats gather at the UN in New York, state, city, and business leaders pledge stronger measures against climate disruption –

MEYER: People are committed. They don't seem to be letting the actions of President Trump and his administration dampen their activism, their level of ambition. If anything, I think it's spurring them on to do even more and more quickly.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

The US Military & Climate Disruption

Citizen-Soldiers of the Puerto Rico National Guard worked on September 11th to clear a highway of debris after Hurricane Irma. Much more destruction came with Hurricane Maria’s direct hit to this island with 3.4 million US citizens just days later. (Photo: Spc. Agustin Montanez / The National Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[HURRICANE SOUND]

CURWOOD: They say it’s like a freight train. Like a woman or a banshee screaming. And this summer hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Jose and Maria howled through trees, houses, schools and businesses, cascading water as they trashed Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, and other Caribbean islands. Even as Commander-in-Chief Trump walks back U.S. climate leadership, his top military commanders are planning for climate-related threats and manning the front lines when they do happen.

Retired Rear Admiral David Titley led the US Navy’s task force on climate change and is now a Professor of Meteorology at Pennsylvania State University. David, welcome back to Living on Earth.

TITLEY: Thank you so much Steve, great to be back.

CURWOOD: Admiral, faced with the devastation in Puerto Rico, what kind of assistance might the U.S. military be likely to give?

TITLEY:The U.S. military will certainly be involved in the disaster relief, along with a lot of other federal Agencies. But just as an example, this morning the Kentucky National Guard is, or part of it, is on their way to Puerto Rico and these are very specialized airman who can get the airfields opening up again, because as you can imagine, when you have this massive storm comes across, you need to get help there but the airfields themselves can be compromised. The runways can be messed up, you don't have the air traffic control stuff any more, so the Air Force has specialists who can rapidly get an airfield back together. Similarly the Navy has people in naval oceanography, we call them a fleet survey team, that when we look at, say, the Port of San Juan, that's going to be need to be opened up so we can get a lot of stuff in there by ship, but my guess is the aids to navigation may be messed up, there might be silting, there might be obstructions in the channel. So all of that stuff has to get picked up rapidly. These are the kinds of capabilities that the Department of Defense will very likely be providing.

In the days before Hurricane Maria hit, the Puerto Rico National Guard coordinated with local emergency management agencies to prepare for the aftermath of the hurricane as well as deal with the continuing effects of Hurricane Irma. (Photo: Spc. Hamiel Irizarry / The National Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And, as we saw in the aftermath of Katrina, the military can be essential for helping to keep order when the civilian authorities are overwhelmed or, frankly, out of commission because of the disaster

TITLEY: Yeah, there's I mean that the Department of Defense in these kind of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations is really very effective at being some of the first people on-scene, although I've I believe FEMA was stationed in places like Guantanamo Bay in Cuba so they can get there very quickly. So this is a team sport, this is inter-agency, it's not just the military but what the military can certainly

provide is communications, logistics, helicopters. Helicopters are worth their weight in gold in the first few days here because just so hard to get around a place. Intelligence, you know all those drones that we hear about and see about in the news, they can be used to really map out, where are people? Where do people need help? How to get water in and again helicopters can be very, very useful for that. Security, as you mentioned, there's probably tenuous security right now, I haven't seen reports, but after a major disaster security is certainly an issue and it's one of those things that the National Guard and the military working with the local authorities whatever local authorities are left and hopefully there are, can help to quickly reestablish order and that allows really everything else to and all the help and all the aid to follow through.

CURWOOD: What we're seeing in Puerto Rico, around Houston, what happened in the Keys, you know, this is in America, where thank heavens we have a fairly stable government system, but when it hits other places that aren't so stable it can really create regional, even international security situations. How important is it for the American military to pay attention to climate change as a security threat from abroad as well as at home?

TITLEY: One of the components of climate change that makes it a threat or a risk, if you will, to national security, is climate change can make already tenuous or frankly bad places much worse and occasionally catastrophically so. But so much depends on the local governance, on the inherent strength, the resilience of the communities affected. This is why you see people like Secretary Mattis talk so strongly about the need for not only the military to be funded but for adequate funding for U.S. Agency for International

Development, or USAID, for our State Department to be adequately funded, adequately manned, because, really, the military can come in initially and try to help stabilize the situation, but the military, the U.S. military is not going to be the one that rebuilds the societies. The military tends to turn these over either to places like the Red Cross, like, you know, large, sustained relief efforts but really for the stability we want our federal partners, really led by the Department of State but with expertise from many other

components of the federal government to play that role, to help stabilize that government because that's really a great way to buy down, if you will, the risk of climate change is to have governments who care about their people, who take care of their people and have the tools and means to do so.

CURWOOD: Now, under the Trump administration which has downplayed the risks of climate change, to what extent is the Pentagon factoring in climate change, climate disruption, as a security threat that requires planning?

In the aftermath of Hurricane Irma, soldiers from the Florida National Guard performed high water search and rescue with members of the Coast Guard and St. Johns Fire Rescue and first responders, in Flagler Estates, Florida. (Photo: Ching Oettel / The National Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

TITLEY: Well I think Secretary Mattis was pretty clear on this early on in his tenure as Secretary of Defense. During his confirmation hearing he was asked some written questions by congressional leaders as to how the secretary would see climate as a as a security risk or a security threat, and Secretary Mattis’s response was, he does understand and does see that the climate is changing and that those changes, if unmanaged, compose a risk to U.S. security operations and U.S. Department of Defense and he said, “Hey this is my job, it's my job to manage risks of all kinds, one of which, one of the many of which, is climate change”. So I thought the Secretary gave a very practical and pragmatic response. He's not going to put climate risk and climate change up on a pedestal and make it the one and only thing we worry about, but

he's also not saying, “Hey this doesn't exist or it's a hoax,” or you know all of the other things that we've heard from other parts of this administration.

In the Department of Defense. I kind of have a saying that says, “If the boss is interested, everybody else is fascinated,” and what that means is since you have the Secretary of Defense talking about climate and climate change in that way it then becomes much easier for his service secretaries, for his assistant secretaries, for the members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to say, “Hey, look, we have these changes

and really for a lot of the readiness of the Department of Defense it doesn't even really matter whyit's changing, but we know it's changing. We know it's changing pretty quickly,” and we’d better be ready for that because if we just plan for the past we're going to be surprised and that's not where the Department of Defense wants to be.

CURWOOD: Now how is the Congress responding to the defense department's interest in studying climate change as a security threat?

TITLEY: Yeah, one of one of the things that to me has been really fascinating this summer is kind of the evolution of climate change as a security risk in our U.S. House of Representatives. So, of course we had the election in November, so, yes, it's a new house from where we were a year ago but one year ago the house with basically the same political makeup passed an Amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act, the main defense bill, that basically said, “Hey, the Department of Defense really should not be worrying about or thinking about climate as a, as a risk. We don't want you to do this now.” That did not survive through all the final negotiations, and it was not signed into law but that was where the house was.

Defense Secretary James Mattis, seen above in March 2017 as he spoke before the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations, testified during his confirmation hearing in January 2017 that he understands the climate is changing and considers it among the many threats the military must be prepared to face. (Photo: Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class Dominique A. Pineiro / Department of Defense, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Fast forward twelve months, you had Jim Langevin, Democrat from Rhode Island, put an amendment into the Defense Act that basically said, “Hey climate change is kind of a big deal especially along the coasts, and the Department of Defense should take this seriously and come back and tell the Congress exactly how you're managing that risk.” It went to the floor of the House and forty six Republicans basically voted to keep that language in the authorization bill, another eight Republicans abstained -- Maybe they realized they needed to freshen up their coffee at Starbucks. I'm not sure -- but that's

over fifty Republicans who, pardon the double negative, but did not vote against climate as a security risk. That's pretty significant I think. Senator McCain just this weekend talked about climate as a security issue.

So we're seeing this evolution in the Congress, maybe, despite all expectations given where the administration is, and I'm actually heartened by this. If you look at this administration I'm not sure they have an ideology on climate or climate change but what that means is, perhaps if the president sees a deal that he thinks is good or he likes it, there might be an opportunity here for, you know, almost a “Nixon to China” moment. Are the odds in favor? Maybe not, but the fact that we see the Congress moving and the

Republicans in Congress moving on this issue I think is a very encouraging sign.

CURWOOD: David, you actually lost a home down on the Mississippi coast at this train as massive storm surge back in 2005. What was it like to go through that experience?

TITLEY: Well, I guess the technical term is it sucks.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

TITLEY: I have to say that my wife and I were probably some of the luckiest people on the Mississippi coast. We had almost none of our personal possessions in that house when the hurricane came, and we did have flood insurance, so financially I was covered. We were very lucky compared to so many others down there.

But I can tell you losing your home in a span of a few hours is a pretty traumatic experience. When we got back down there, it turned out that all we had is, you know, we were elevated to the FEMA flood standard, not that it did any good. So we had about half a dozen green posts sticking out of a concrete slab and there was really nothing else on our lot. So I tell people to this day, “When we lost our house we really literally lost our house.” We have no idea where it went. It either got sucked back out into

the ocean or maybe put up into the railway embankment along with pretty much everybody else's house. But the good news is I didn't have to clean up much on our, on our lot because it really was nothing.

Rear Admiral USN (Retired) David W. Titley is a Professor of Meteorology and Founding Director of the Center for Solutions to Weather and Climate Risk at Pennsylvania State University. Now retired from the Navy, he initiated and led the US Navy Task Force on Climate Change. (Photo: courtesy of David Titley)

But then you're in the same position that everybody else is. You're trying to figure out just very basics like, where do you live, are you going to stay, are you going to go, are you going to rebuild? If you're going to rebuild, are you going to rebuild the same way that you had it before? Are you going to go up in elevation? are you going to go inland? How are you going to get the services? Because it's not only you, it's now, you know, one hundred thousand of your closest friends and neighbors want those exact same services at that exact same time. How do you know if you find a contractor that that contractor is a good person, that you're not going to get ripped off, it's not somebody who's kind of come in to take advantage of these situations? All of these things everybody is dealing with, and I'll guarantee you that people in Texas are dealing with this. Many people in Florida and tragically many people in the U.S. Virgin Islands as well as the other Caribbean nations and Puerto Rico are going to go through this, and it takes a long time. It takes years, and there's just nothing fun about it. It's just hard work, a lot of uncertainty, a ton of decisions. You spend a lot of time wishing that you could just have your life back like it was the day before the storm hit. It's hard, I really, really feel for the people that have been affected by these three storms.

CURWOOD: David Titley is a retired admiral and currently a Professor of Meteorology at Pennsylvania State University. Thank you so much, Admiral, for taking the time with us today!

TITLEY: Thank you so much Steve. I appreciate you having me on.

Related links:

- ProPublica: “Trump’s Defense Secretary Cites Climate Change as National Security Challenge”

- Washington Post: “Hurricane Maria churns through Caribbean as ravaged Puerto Rico takes stock of an ‘island destroyed’”

- Business Insider: “46 House Republicans join Democrats in backing a US military study on climate-change threats”

MUSIC: Liz Bruce-Lomba, “Stormy Weather” composed by Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler, not commercially available]

CURWOOD: Coming up, states, cities and companies have ambitious plans to fight global warming, despite the seeming indifference of President Trump. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Michael Hedges, “Rickover’s Dream” on Beyond Boundaries – Guitar Solos, Windham Hill]

Climate Week 2017

For the past four years, the empire state building has been illuminated in green in honor of Climate Week NYC. (Photo: Arturo Partivilla II, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

When the world’s leaders gather in New York for the annual fall meeting of the UN General Assembly, there is also a series of meetings called Climate Week that allows all those government, business and NGO leaders to discuss global climate solutions. This year, those consultations have an added urgency. Not only has President Donald Trump said he’s pulling the US out of the UN Paris Climate Agreement, but an unprecedented succession of huge and deadly hurricanes has also been battering the US and the Caribbean.

Alden Meyer, a climate diplomacy expert with the Union of Concerned Scientists, came to New York City for Climate week, and joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Alden.

MEYER: Good to be with you again, Steve.

CURWOOD: Tell me, what's the mood been like at the climate week there in New York?

MEYER: Well it's, it's a strange mix. You have event after event where cities and states and companies are making commitments to climate action. There was the launch of the EV100 Alliance, where a coalition of global companies, including Unilever, Ikea, D.H.L., and others have committed to try to replace their fleets with electric vehicles, and earlier you had Governors Cuomo, Jerry Brown of California and Jay Inslee from Washington state announce the U.S. Climate Alliance of fourteen states and ironically Puerto Rico, committed to meeting their share of the U.S. Paris commitment, despite what President Trump is doing.

Of course in contrast you have President Trump giving a speech, his maiden speech to the United Nations General Assembly where he didn't mention the words ‘climate change’ and despite talking about security risks and instability around the world, didn't make the obvious connection between what we're doing to pump up global warming pollution and the impacts that that's already having around the world. So it is this kind of strange confluence of optimism and urgency that's coming together here. But people are committed. They don't seem to be letting the actions of President Trump and his administration dampen their activism, their level of ambition. If anything I think it's spurring them on to do even more and more quickly.

CURWOOD: All these intense storms here in the U.S. -- Harvey, Irma, Maria -- How is that affecting the discussions at the climate week, and how is it affecting you?

MEYER: Well it certainly is a topic of discussion here, it's concentrating minds. Of course there are colleagues from the Caribbean that are not able to be here, that had planned to be here for these meetings and these discussions because of what's going back on in their home countries. It is on everyone's mind, it underscores the urgency of the problem, and it certainly has affected me and my thinking about this -- just to have these reports on the T.V., on the radio every day about what's going on, to see the devastation in places that I and my family have visited like the Virgin Islands. It really just gives you pause.

We will see what impact it has the U.S. policy scene, on the White House, on the administration, on the Congress. We'll see if it makes any difference in the conversation certainly as the Congress has to consider disaster relief and financial aid over the next several months to these states and regions. Of course Puerto Rico is, is U.S. jurisdiction and I think that will be an opportunity to also have the longer term discussion about what we're doing and are we doing our fair share.

A gathering of environment ministers from the world’s major economies recently took place in Montreal and was hosted by Canada, China and the European Union. The Canadian Minister for the Environment and Climate Change, Catherine McKenna, expressed the critical nature of these meetings to fighting climate change. (Photo: VAC | AAC, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, Donald Trump, of course, announced that he pulling the US out of the Paris Agreement which would take until 2020 to actually put into effect. What do you make of the vote in the Senate recently in a committee to restore to the State Department's budget money necessary for the US State Department to participate in the Paris Agreement, to pay for their seat at the table?

MEYER: Well, I think that was important. It's the money for the operations of the United Nations Framework Convention Secretariat as well as our contribution to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is around ten million dollars a year that money was zeroed out in the Trump budget proposal and zeroed out in the House bills as they move through the process, but in the Senate you had an amendment by Senator Jeff Merkley from Oregon to restore that funding, and he was able to get the support of two Republicans, Lamar Alexander from Tennessee and Susan Collins from Maine, and allowed him to win the votes and put that money back in. I think the big question will be when the Senate bill goes to conference later this year with the House version of the bill and with the administration not supporting it, what the final outcome would be.

But I think it shows that there's an understanding that if you're going to be part of these institutions, part of these agreements that you need to pay your share of operating them and of course President Trump announced he intended to withdraw the US from Paris but not from the underlying framework convention that was agreed to by President George H.W. Bush in Rio in 1992. So I take it as a good sign we're going to be fighting along with many other groups to make sure that funding is maintained throughout the rest of the process but there's still a lot of heavy lifting ahead.

CURWOOD: So, what are your thoughts on the buzz the president trying to reverse his Paris decision, say, issue a new U.S. target and say that he's won and rejoin?

MEYER: Well this is an ongoing discussion since the Rose Garden speech he gave on June 1st where he falsely claimed that the Paris Agreement put the United States at a competitive disadvantage and that other countries were laughing at us because we took on this obligatory burden, none of which of course is true, but even in that speech he left the door open saying, if we could renegotiate the agreement to be more favorable to the U.S. he might change his mind. I think what's become clear since then is that other countries are not open to renegotiating the agreement itself, and the United States has pretty much dropped any claim in that area. The phrase now is “reengagement”. Will the U.S. reengage with Paris?

One route there could be for the Trump administration to put forward a less ambitious national target for emissions reductions in the U.S. They also could engage in the negotiations over the implementation rules for Paris, things like reporting by countries like China and India and how well they're doing in meeting the commitments they made. But there's a bit of Kabuki play, I think, going on here. Part of this is to keep the international community perhaps hoping the President Trump will change his mind and stay in Paris when there's no real indications from the president himself that he's really thinking that way in order to prevent more severe diplomatic blowback from the world for the US abandoning Paris.

Alden Meyer is director of strategy and policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists and the director of its Washington, D.C. office. (Photo: Union of Concerned Scientists)

CURWOOD: What do you make of the recent meeting in Montreal that Canada convened with China and the E.U. to address elements of the Paris Agreement?

MEYER: That was a very significant meeting, not necessarily for the substance that came out of it because it was the first meeting of those three countries that hosted, but by the fact that they stepped into the vacuum created by the Trump administration because, as you know, President Obama and before him President Bush had hosted what were called the major Economy Forum meetings, the so-called MEF meetings, and I think having China in particular join the European Union and Canada in stepping into that vacuum and offering leadership to maintain that kind of dialogue is significant. They've announced Europe will host a meeting in the first half of next year in Brussels, and China will host a meeting in the second half of the year in China, so it's a significant issue and a forum that I think can be useful, but this was just the first introductory meeting.

CURWOOD: Now, come November there'll be another conference of the parties for the big U.N. Framework Convention as well as the Paris process. What are the big agenda items that need to be accomplished at that meeting, just right around the corner now?

MEYER: Yeah, well there are a number that have to be accomplished. One is they have to make significant progress on these implementation rules for Paris, things like reporting guidelines, accounting standards, financial elements, the new market mechanisms that were created in Paris to allow countries to collaborate in reducing their emissions, land use change issues, the issues of adaptation, loss and damage. There's a whole series of detailed rules that they aim to adopt by the end of next year, and of course the original intent of Paris was that by 2020 all countries would take a harder look at the commitments they made in 2015, sharpen their pencils, and see if they could do more.

But then of course there will be also discussions, and I think particularly in the wake of this week's intense storms in the Caribbean and the US, of the issue that's called loss and damage. What do you do to help countries that are grappling with the unavoidable impacts of climate change, even if we do as much as we can to reduce emissions and limit the temperature increase. We're already just at about one degree Celsius increase in temperature over pre-industrial levels, and you can see the extreme weather events that we're now seeing around the world, so even if we succeed in holding temperature increases well below two degrees, as opposed to the three and a half or four degree path they were on now, those impacts are going to continue to mount, and particularly the vulnerable countries need help dealing with them, preparing for them, recovering from them.

CURWOOD: How does that make you feel?

MEYER: Well, it obviously is very concerning. It makes me sad on a deep level because we've been predicting this, not only my organization but the scientific community globally and many others around the world, that this is exactly what we would be experiencing if we didn't take more aggressive action, and I think it's an indication that we're running out of time. But on the optimistic side, the response of other countries, of governors, of mayors, of the business community to this problem, the dramatic reduction in the costs and availability of clean solutions like wind and solar energy gives me hope. So again, you know it's that strange bittersweet mix of some despair along with some hope, and you just have to put one foot in front of the other and keep doing what you can based on where you are and whatever access and influence you have to keep trying to influence the process and drive quicker action.

CURWOOD: Alden Meyer is Director of Strategy and Policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much Alden.

MEYER: Always a pleasure thank Steve, it was good to be with you.

Related links:

- Bonn 2017 November Meeting of the UNFCCC

- Climate Week NYC 2017

- Reuters: “U.S. attends meeting on Paris climate accord, still plans to withdraw”

- Alden Meyer Union of Concerned Scientists Profile

[MUSIC: Guy Mendilow Ensemble, “Durme, Durme” on The Forgotten Kingdom, tradition Sephardic lullaby, Guy Mendilow Music]

Beyond the Headlines

The government of the Seychelles, a 115-island archipelago in the Indian Ocean, is considering a proposal for what would be one of the world’s largest marine sanctuaries. (Photo: Jean-Marie Hullot, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let’s take a trip to Georgia now to catch up with Peter Dykstra and what’s happening beyond the headlines. Peter’s with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn dot org and DailyClimate dot org and he’s on the line from Brookhaven. Hey there, Peter, what’s going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. In keeping with an all-too-rare tradition, let's try to get some good environmental news in here.

CURWOOD: Good news is always welcome, so fire away.

DYKSTRA: The Seychelles are a beautiful island archipelago in the Indian Ocean surrounded by some of the most unexploited ocean areas left in the world. And the Seychelles Government is now looking at a proposal for a huge marine reserve -- one of the world's biggest -- and one that would come on the heels of another announcement of the world's biggest marine sanctuary around Easter Island in the Pacific.

CURWOOD: So let's back up a minute Peter ... Marine reserves, marine sanctuaries, these are uh, well they’re kind of national parks of the oceans, right?

DYKSTRA: Correct, and protecting huge swaths of that ocean from commercial activity -- fishing, deep-sea mining, drilling, and a lot more -- is a big step toward preserving some sort of legacy. Just like Teddy Roosevelt and others did a century ago with protected land areas like Yellowstone and Yosemite, modern-day conservationists view themselves as protecting oceanic national parks in the same way.

CURWOOD: Peter, not to wash a wave over your campfire, but aren't these marine sanctuaries on the high seas hard to police? I mean their areas are as big as the state of Texas, and they’ve got one boat, maybe two patrol boats to guard them?

While the aftermath of hurricanes continue to affect residents, such as those in Houston, Texas devastated by Hurricane Harvey (above), research has found that the frequency and intensity of these latest storms have done little to shift public opinion about their connection with global warming. (Photo: Texas Military Department, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well that’s a valid point, policing is a major concern, but it's at least getting a little easier to patrol them. The same kind of satellite technology that allows other nations to monitor things like North Korean nuclear activity allows us to follow illegal fishing boats into protected water. The tiny Pacific island nation of Palau has already seized a couple of boats in this manner for illegal fishing in its marine sanctuary.

A specific about this latest deal -- the Seychelles swung a huge arrangement with the nonprofit Nature Conservancy, which will pick up millions of the tiny nation's international debt in exchange for limiting tuna fishing and other commercial activity in its waters.

CURWOOD: Hmm, a debt-for-tuna swap. Of course, back home here, Interior Secretary Zinke would like to see more fishing in some US Marine Monuments. Hey Peter, what's your next topic this week?

DYKSTRA: This one’s from academics at the Indiana University and the National University of Australia. They say that even after scientists tell us that storms, and droughts and floods are very likely made more frequent and intense by climate change, a season of such catastrophic storms hasn’t done much to change public opinion.

CURWOOD: So you’re telling me that Harvey, Irma, Maria, these killer Atlantic hurricanes, won't move the needle much?

DYKSTRA: Surprisingly little, and only for a short period of time, according to this research which was published this month in the Journal of Environmental Change. The huge damage that’s been done in Texas, and Florida and the Caribbean, climate advocates have had little success pressing their arguments that even these mega-storms should move hearts and minds the way they moved coastlines.

CURWOOD: Alright, well let's move on now to the land of learning from past mistakes, our weekly voyage through the history files.

DYKSTRA: Sometimes we do learn from history, and this one can hopefully be one of those times -- specifically that time when Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher joined other world leaders in an environmental breakthrough that's bearing fruit today.

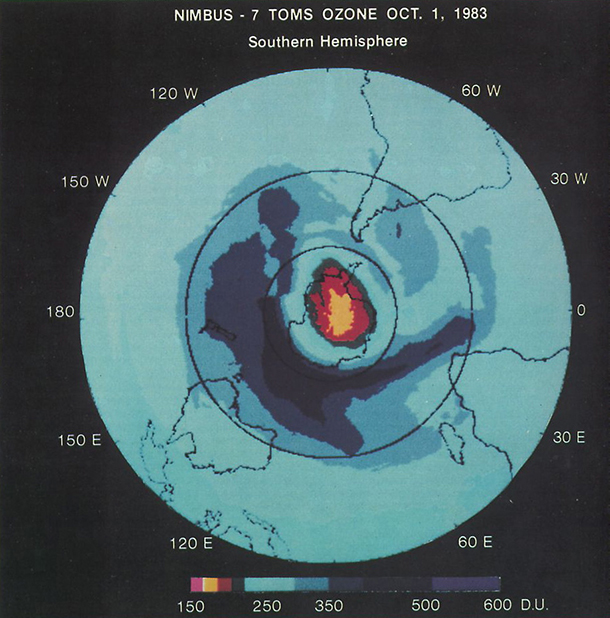

This image of the ozone hole above the Antarctic, taken in 1985, helped lead to the Montreal Protocol. In 1987, the U.S. and the U.K signed on to this historic agreement to limit emissions of ozone-destroying chemicals like chlorofluorocarbons. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Thirty years ago, 25 nations including Reagan's United States and Thatcher's United Kingdom, signed on to the Montreal Protocol, the global effort that came together to close the growing ozone holes over the Arctic and the Antarctic.

CURWOOD: Those holes threatened to expose humans and wildlife to the harmful UV radiation normally kept out by the earth's protective layer of stratospheric ozone.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, the treaty’s worked to phase out ozone-destroying chemicals like chloroflurocarbons from the earth's upper atmosphere, resulting in projections that our ozone holes will some day heal themselves, and in fact, they've already begun to do so.

CURWOOD: So we had good news to start and good news to finish, Peter - Thanks!

DYKSTRA: Alright Steve, thanks a lot. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with DailyClimate dot org and Environmental Health News, ehn dot org – and there’s more on these stories at our website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- The Economist: “A new plan to protect the water around the Seychelles”

- The Arizona Daily Sun: “News Analysis: Monster storms change coastlines, not minds on climate change”

- The Revelator: “After 30 years, the Montreal Protocol is paying ozone dividends”

BirdNote®: Roosting Tree Swallows

During the Northern Hemisphere’s summer, tree swallows inhabit much of the Western and Northern United States and most of Canada. But come fall, these birds migrate to the Gulf Coast, the Caribbean, and Central America. (Photo: Mike Hamilton, CC)

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: Here on the east coast of the US the autumnal equinox came shortly after four in the afternoon on September 22, and the days are growing noticeably shorter. But many of the songsters of summer are still with us and as Mary McCann points out in today’s BirdNote, they continue to put on spectacular shows.

BirdNote®

Tree Swallow Roost –

The Swarm in Connecticut

[MULTIPLE TREE SWALLOWS CALLING; WAVES LAPPING AGAINST A BOAT]

As the sun sets over the Connecticut River, an astounding natural spectacle unfolds. As many as

300,000 sparkling blue swallows—Tree Swallows—wing their way from miles around, to roost for

the evening on Goose Island, near Old Lyme.

[MULTIPLE TREE SWALLOWS CALLING; WAVES LAPPING AGAINST A BOAT]

The birds gather on the wing in one immense, tightly choreographed flock, a swirling mass that

changes shape from one second to the next, like an immense silken banner or plume of smoke racing

with the wind. With dusk at hand, the aerobatic flock – now shaped like a tornado – swoops down into

the island’s tall reeds. It takes but 15 seconds for the 300,000 birds to vanish into the marsh, where they

remain until dawn.

[CALL OF TREE SWALLOW FLOCK]

Tree Swallows travel in massive flocks. On a recent, late-summer evening, around 300,000 of them gathered from miles around to roost on Goose Island in Connecticut. (Photo: Dan Irizzary, CC)

Roger Tory Peterson, dean of American birdwatching, wrote of the swallows: “I have seen a million

flamingos on the lakes of East Africa and as many seabirds on the cliffs of the Alaska Pribilofs, but for

sheer drama, the tornadoes of tree swallows eclipsed any other avian spectacle I have ever seen." *

[TREE SWALLOWS CALLING]

Soon all of Goose Island’s swallows will disappear below the southern horizon for the winter. But

witnesses will long remember the autumnal spectacle of the birds’ massed flight.

[TREE SWALLOWS CALLING]

Tree Swallows coast to coast are swirling down to roost this month. Maybe there’s a roost near you.

I’m Mary McCann.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Call of Tree Swallow flock provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Song recorded by

G.F. Budney. Massive flock sounds recorded by O.H. Hewitt.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2008-2017 Tune In to Nature.org September 2017 Narrator: Mary McCann

Tree Swallow photo by Dan Dzurisin https://www.flickr.com/photos/ndomer73/2544385868/

Tree Swallows coming to roost, by Dan Irizarry https://www.flickr.com/photos/danirizarry/6628440837/

*Peterson quotation taken from RiverQuest tour ad for swallow trips.

CURWOOD: And for photos, try our roost, the website loe dot org.

Related links:

- The story about the tree swallows on the BirdNote® website

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology: About the Tree Swallow

[MUSIC: Jay Ungar & Molly Mason With Fiddle Fever, “Ashokan Farwell” on The Civil War Classics 2000, Columbia Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, You might think English is the most widely used language, but you’d be wrong.

That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies – combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Paul Glasse, “Air Mail Special” on The Road To Home, composed by Benny Goodman, James Mundy and Charlie Christian, Dos Records/Ka]

Science Note: The World’s Most Common Language, It Seems

Though this Fusarium fungus may not look especially chatty, it actually engages in active discussion. Researchers from the Netherlands Institute of Ecology have discovered that Fusarium release chemical fragrances called terpenes to communicate with bacteria. (Photo: Oregon State University, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. In a moment, how the proverbial chicken in every pot became so cheap and potentially deadly, but first this note on emerging science from Noble Ingram.

[MUSIC: SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

INGRAM: The world’s most widely-used language isn’t English, Spanish or Mandarin. It isn’t even spoken; it’s smelled.

A sweeping variety of organisms use chemical fragrances called terpenes to communicate. Now, a research team from the Netherlands Institute of Ecology has found new evidence linking microorganisms to this silent language.

For years, scientists have known that plants and insects use terpenes to send signals, as mammals do with pheromones. But the research team discovered that smelly messages are also exchanged between microorganisms, including fungi and bacteria. The new findings add trillions of life forms to terpenes’ list of fluent speakers.

In the study, a fungus called Fusarium produced terpenes that were picked up by a neighboring soil bacteria called Serratia. The Serratia then responded, expelling their own scent signals that were crafted specifically for the Fusarium. What exactly was being communicated remains unclear but the team says the interaction was a recognizable call and response.

While humanity struggles to bridge language gaps within its own species, these tiny lifeforms have been chatting with each other across phylogenetic domains. But despite our limited linguistic abilities, we might unknowingly be joining the conversation. Terpenes are also popular ingredients in perfumes. These biochemicals provide natural notes, like juniper, lemon, and eucalyptus to an aromatic blend.

So next time you catch a whiff of fancy cologne, consider it a ‘hello’. After all, plenty of microorganisms do.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Noble Ingram.

Related links:

- The microorganism communication study in the journal Nature

- Netherlands Institute of Ecology: “The world’s most spoken language is… Terpene”

[MUSIC: SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Big Chicken

Chickens in an industrial poultry farming facility. (Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Back in 1970, the average American ate less than a pound of chicken each week. Today it’s more than twice that. And in the rush to bring all that poultry to market some industrial scale producers relied on antibiotics to keep infections down in their massive factory farms. But as the wisdom of that has been questioned, a lot of chicken producers are scaling back on their wholesale use of antibiotics.

For an update on this trend we turn now to Maryn McKenna, who has written a new book called Big Chicken. Maryn McKenna is a journalist and author who focuses on public health and food policy, and she joins us now from Atlanta, Georgia. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MCKENNA: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Now, we've known about the risks of antibiotics in agriculture and livestock for a long time. What prompted you to begin writing this particular book? I know you've been active in this area for much of your career as well.

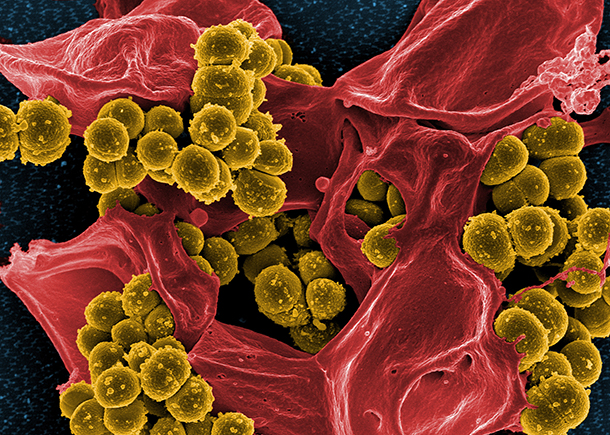

MCKENNA: So, the reason why I wanted to look at this was really twofold. The first was, seven years ago I wrote a book about antibiotic resistance generally. It's called "Superbug", and it was my attempt to tell the story of the emergence of antibiotic resistance by sort of telling the biography of a single organism, MRSA, or drug resistant staph. And I went into that project thinking that I knew what the story was, that there were two epidemics of staph, in hospitals and in the wider world, what's called Community Associated MRSA. That's the staph that affects kids in school and has ruined the careers of a lot of pro athletes, and it turned out that that was wrong. There were actually three epidemics of drug resistant staph around the world, in hospitals, in the community, and also in farms, and the statistics that I stumbled across in researching that were that we use in the United States four times as many antibiotics in animals as we are in humans, and that just made no sense to me because I just emerged from talking to people who are saying, “We have to be conservative with antibiotics. We hasve to be very careful how we use them.” And yet here on the agricultural side people were tossing antibiotics by the literal ton into animal feed.

Scanning electron micrograph of methicillin-resistant Staphylococccus aureus (MRSA) and a dead human neutrophil. (Photo: NIAID, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So in your work on MRSA you found that not just the hospital, not just the locker room, but, whoa, on farms and among farm workers. But how is the antibiotic drug resistance in the poultry industry different or unique compared to what happens for human antibiotic use?

MCKENNA: Well, in some ways it's not unique at all. The problem with farm antibiotic use is that we use the exact same antibiotics in farm animals that we do to treat human infections. What the implications of that are that if a resistant bacteria arises in animals as a result of that antibiotic use and then travels off the farm to affect humans in some way, then the drugs that we would have relied on no longer work because they've been undermined by that use on the farm, and the big fight over farm antibiotic use, pretty much from its inception, has been whether those bacteria actually do travel off the farm. They're not just resident with the animals, but they affect human health far from the farm, and I think it's very well established now that that is the case, that it does have a broad effect, but it was tracing that chain of evidence that was one of the things that made me want to do this project and write this book.

CURWOOD: And talk to us about why farmers started using antibiotics back after they were discovered and particularly the economic conditions that made it advantageous for that.

MCKENNA: So, like a lot of things. This is kind of a story of good intentions gone awry. So, immediately after World War II, several things are happening. First, it's the start of the antibiotic era. Penicillin's out in 1944, 1945, and there's great rejoicing at how powerful these drugs are to reverse infectious diseases. At the same time the food production system has been really undermined by the war, and there's a great deal of excess capacity because all those troops were being fed and now all those troops have gone home. So, out of that desire to protect the food production system while also cutting costs, comes this idea of using antibiotics as what are called "growth promoters", which are tiny doses that you give animals routinely that somewhat mysteriously at the time cause them to put on weight much faster than they would have otherwise. Now, we would recognize that today as being a disruption of the gut microbiome that affects nutrient uptake, but in the 1940s and 1950s, they didn't really know what was going on. They just knew that it worked.

CURWOOD: And in fact today as you point out it doesn't make these chickens any fatter, to use this.

MCKENNA: It's true, and it's not just chickens. You know, this goes on in pigs and this goes on in cattle as well, and all the major meat eating animals. It is absolutely true that in the United States and in Western Europe growth promoters don't work anywhere near as well as they once did. That's probably one of the reasons why industry was willing to give them up in response to this Obama administration pressure, but they're still very much used in the developing world, and that is going to be where the fight over this turns now because in conditions of more crowding, of less hygiene, of less precision nutrition, all of which we take for granted in agriculture in the United States, but we can't take for granted in the developing world. Growth promoters and preventive uses of antibiotics in animals are still really valuable, but they still have the same resistance promoting effect.

Antibiotics helped chicken to become the most consumed type of meat in the U.S. (Photo: Peter Cooper, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: There is a basic thing about antibiotics and livestock, and that is producers are tempted to use them more and more in crowded and not healthy conditions. To what extent do these antibiotics allow for these huge factory farms that you talk about to exist, A, in the United States but, B, overseas?

MCKENNA: So, using antibiotics routinely in farm animals does two things. The first is this growth-promoting effect where you give them very small doses, literal grams per ton of feed, and it causes them to put on tasty muscle faster, and to me that's the thing that really starts the whole ball rolling for what we now think of as industrial scale agriculture because once you can produce animals a little more quickly or a little more cheaply, it becomes tempting, I think, to do that more and more. And so, we start to move toward the farms that are running in a more mechanized fashion. Then, as they get bigger, someone has the idea to use just a little more antibiotic. Still, doses far below what it would take to cure an infection, but enough that it protects the animals from being in such close quarters with each other, and so we get a very efficient system for growing very inexpensive protein, but with the downside of resistant bacteria being created in a way that no one really intended, but for a long time no one really took account of, either.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about food poisoning and its connection to the widespread use of antibiotics in livestock. In your book, you mention a case actually involving egg processing that there was a substantial Salmonella outbreak, and we know even today organizations like the Consumer's Union will publish studies saying that a fairly large percentage of poultry has a lot of unhappy bacteria on it, whether it's Salmonella or Listeria. How is that related to this overuse, in your view, of antibiotics?

MCKENNA: So, back before the growing of meat animals became industrialized, when farms were still pretty small, if there was an outbreak of food borne illness, it was usually a pretty local one, and you had a fairly good sense of where it was coming from, whether it was from a particular farmer or a particular dinner or a particular place where a small group of people had eaten. As farms get larger and larger, and the industry collapses into larger companies that are sending the foods that they produce across greater distances, first, food borne illness outbreaks get larger, and they also get much more spread out so they're harder to solve.

McKenna’s new book follows the history of antibiotics in modern agriculture. (Photo: courtesy of Holly Watson PR)

Then, add antibiotics on top of that. So, the bacteria that cause foodborne illness are bacteria that come from the animals' guts, and, when you are feeding antibiotics to those animals, the antibiotics are going into their guts as well and influencing the bacteria in their guts to turn toward antibiotic resistance. Those bacteria may get on the meat that those animals are becoming and travel with them into the food system, into home kitchens, into restaurant kitchens, into supermarkets. So, you get for the first time, both antibiotic-resistant food-borne illness and also outbreaks of food-borne illness that are much harder to track back to the places that they come from than they would formerly have been. So, while it's the concentration of agriculture that starts the ball rolling for larger more diffuse outbreaks of food-borne illness, adding antibiotics to the mix makes them much more dangerous.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the animal welfare part of the overuse of antibiotics.

MCKENNA: So, the thing about using antibiotics routinely, and I want to be clear here that the antibiotic use that deserves scrutiny is not antibiotic use that cures infections in animals that are sick. What we're talking about here is antibiotic use in animals that are not sick for purposes other than curing infections. If we did that in humans, medicine would immediately consider that to be inappropriate. We only use antibiotics to cure infections in humans. We overwhelmingly don't do that in agriculture. So, once you start protecting animals from the consequences of the way that you're keeping them, whether that's feeding them lower quality protein or cramming them together in a barn or feedlot in a density that they wouldn't naturally be able to tolerate, then their quality of life naturally goes down.

CURWOOD: Now, Maryn, you wrote that attempts to regulate antibiotic uses on farms started in the 70s but usually failed. What happened? What were the conditions that prevented policymakers from curbing antibiotic use in agriculture back then?

MCKENNA: So, the story of how we almost got in the United States to regulating this practice is really a sad story. So, to set the stage a little bit, this widespread use of antibiotics on farms is happening by the mid-1950s. The first troublesome outbreaks of antibiotic resistant food-borne illness are happening by the mid-1960s, and by the end of the 1960s, the first government to take a look at this is actually the British government, which by 1971, restricts all growth promoters. And that turns attention back to the United States since we are the home of this antibiotic use and a much, much larger agricultural economy.

So, the Carter administration comes in 1976, and they decide that one of the things that they're going to do is they're going to reverse this FDA policy, these licenses granted in the 1950s. So, there's a very activist new FDA commissioner. His name is Donald Kennedy, and he sends a message to the manufacturers of veterinary antibiotics which are most of the large pharma companies in the country. He puts a notice in the Federal Register saying he's going to summon all of them to a hearing. And at that hearing he's going to ask them all to prove that their products as used in agriculture are safe. And if they can't prove that, then he's going to yank the licenses, and he never gets to hold that hearing because a very powerful Congressman from the south who has oversight over the FDA's budget sends a message up to the Carter White House that, if this hearing goes ahead, then this Congressman will hold the FDA's entire budget hostage, and thus the opportunity goes away. That Commissioner Donald Kennedy is on loan from Stanford University, and within a couple of years he has to go back, and the Congressman Jamie Whitten puts a rider on the appropriation bills for basically the rest of his tenure in the House of Representatives saying that antibiotic use in agriculture cannot be re-regulated by the FDA, and he keeps that rider going until he retires in the 1990s.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about how the political landscape has changed. Particularly, you say the year 2013 is a pivotal year in this story. What makes that year so significant?

MCKENNA: So, this stalemate that the government and agriculture and the veterinary pharma industry are in goes on for decades, and then a whole bunch of pieces of the landscape change. That stubborn Congressman retires, and the Obama administration comes in in 2009 and somewhat mysteriously decides that they are going to make this one of their issues, and one of the things they do is they say to the FDA, “Let's revisit what was supposed to happen in 1977, but was prevented.” So, at the end of 2013, the FDA moves to do a thing that in 1977 they didn't think about. They propose not a law and not a regulation - because both of those could be interfered with by Congress - but instead a semi-voluntary measure that they call a “guidance,” which is something that the FDA can do without any of the other branches of government touching it.

Maryn McKenna is a journalist and author who has reported on antibiotic drug resistance through much of her career. (Photo: courtesy of Maryn McKenna)

So, they put forth a set of guidances that recommend that drug manufacturers change the labels on their drugs so they can no longer be used as growth promoters on farms, and somewhat to everyone's surprise all of the pharma industry falls in line. The FDA gives the industry three years to try this, from the end of 2013 to the end of 2016. All of the pharma manufacturers agree, and so, as of January 1st of this year, to use antibiotics as growth promoters is effectively illegal in the United States, putting us in line with what Europe did more than 10 years ago.

CURWOOD: Maryn, from your perspective, what are the alternative models to raise chickens in more environmentally and economically and sustainable ways, and some would say even more humane ways?

MCKENNA: So, the thing that I think is really interesting about this is that giving up antibiotics has created a kind of ripple effect through the industry in a few different ways. First, it opens up the market, I think, to the small and medium sized producers who want to raise birds in an extremely high welfare, out on pasture, very old-fashioned looking manner. Those birds are allowed to live a lot longer, they exercise, they have what look like happy lives. They also taste different, and they are a challenge for consumers to embrace, but forgoing antibiotics has also caused the major producers to really start making other changes in their production as well.

The best example of this is Purdue Foods, Purdue Farms, and they have said to me reconsidering antibiotics caused us to rethink an awful lot of other things about the way we raise our chicken, and now they're doing things like cutting windows in the walls of their barns and putting herbs and probiotics and prebiotics into their chickens’ diets and allowing the chickens to exercise. So, rethinking antibiotics, I think, is changing the entire way this protein, chickens, are produced. And the question will be, then, can chicken teach the rest of the meat economy that this is the way that's worth going?

CURWOOD: Maryn McKenna is a journalist and author. Her new book is called "Big Chicken: The Incredible Story of How Antibiotics Created Modern Agriculture and Changed the Way the World Eats". Thanks so much, Maryn, for taking the time.

MCKENNA: Thank you for having me.

Related link:

Big Chicken: The Incredible Story of How Antibiotics Created Modern Agriculture and Changed the Way the World Eats

[MUSIC: Asleep At the Wheel, “Ain’t Nobody Here But Us Chickens” on Collision Course, by Alex Kramer and Joan Whitney, Capitol Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Olivia Reardon, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth