January 19, 2018

Air Date: January 19, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Migratory Bird Protections Under Fire

View the page for this story

Seventeen former Department of Interior officials have written a letter protesting a new DOI ruling that exempts industry for negligent deaths of birds , and may violate the century-old Migratory Bird Treaty with Canada and other nations. Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood spoke with Paul Schmidt, a former Fish and Wildlife official who served administrations from Presidents Carter through Obama. (07:53)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In keeping with this week’s theme, Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood discuss a new and surprising danger to an already threatened bird: the Northern Spotted Owl. Also subject to new environmental dangers is the Giant Panda, according to recent research. For this week’s history lesson, Peter Dykstra recalls William O. Douglas, the greenest judge to ever sit on the U.S. Supreme Court. (03:23)

Making a Bird List and Checking It Twice

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

At Christmastime every year, tens of thousands of birdwatchers across the country head out for an annual count. They record every bird they see for the Audubon Society's Christmas Bird Count, now in its 118th year. These citizen scientists provide important data for academics and decision-makers. Living on Earth's Jenni Doering follows California Oceanside teams as they hunt for birds at lagoons, saltwater marshes and beaches. (11:20)

Babysitting Arctic Terns

View the page for this story

Arctic terns undertake the longest known migration on earth, travelling more than 50,000 miles per year. But reduced habitat threatens nesting sites. Gwen Potter is a countryside manager at National Trust, a British conservation organization. She tells host Steve Curwood about their tern babysitting endeavor that helped dramatically increase the number of fledglings on the Northumberland coast. (06:51)

Year of the Bird

View the page for this story

National Geographic, the National Audubon Society and other conservation groups, have declared 2018 the Year of The Bird to celebrate the centennial of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. National Geographic writer and novelist Jonathan Franzen is a keen birder who wrote Nat Geo’s January cover story. He tells host Steve Curwood how a walk in New York City’s Central Park opened his eyes to the pleasures of birdwatching, why the Treaty was necessary a century ago and the many perils that birds still face today. (14:24)

BirdNote®: Help Screech-Owls Find Homes

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

The tree cavities left behind by woodpeckers are an ideal home for Screech-Owls, but they’re often in short supply. In this BirdNote®, Michael Stein describes how you can make an enticing home for a Screech-Owl pair, with just a few pieces of wood, a saw and a spare hour or two. (01:46)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Paul Schmidt, Gwen Potter, Jonathan Franzen

REPORTERS: Jenni Doering, Peter Dykstra, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. In the Year of the Bird, celebrating more than a century of the Christmas Bird count.

MORROW: Before the 1900s, the common thing to do was to go out on a Christmas bird hunt and shoot as many birds as you could, and then you would gather together and count up the number of birds that you’d killed to see who was the winner. And that did not sit well with some of the birders.

CURWOOD: When the passenger pigeon was gone – Americans responded to save the rest.

FRANZEN: So suddenly we had the invention of bird conservation - the creation of the Audubon Society and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which is under threat in the current congress and it's also under threat by the Department of the Interior, which wants to de-fang that law and make it OK to kill birds without having to pay any consequences.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Migratory Bird Protections Under Fire

Snow geese migration. (Photo: John Carrell, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. If there is one group of creatures that nature has endowed with command of Planet Earth, it has to be the birds. They can fly, swim, and walk, and they are especially adept at ignoring the borders based on politics. And our show this week is all about birds, as 2018 is the centennial year of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which National Geographic and Audubon, and others are celebrating as the Year of the Bird.

We begin with some irony, though. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act and related rules have helped safeguard many birds over the past century, but the Trump Administration has reinterpreted it in a way that would loosen its protections, and shield companies that kill birds from prosecution. That new interpretation has prompted a protest letter from some 17 former wildlife officials from both Republican and Democratic administrations. The letter organizer is Paul Schmidt, who served the Carter through Obama Administrations. Welcome to Living on Earth!

SCHMIDT: Thank you, I’m glad to be here, Steve and Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Now, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, what's the purpose of this act?

SCHMIDT: Well, the original purpose was actually to establish a continental approach to managing and conserving migratory birds, about a century ago, actually. It began with a treaty with Canada back in 1916, when folks realized that migratory birds don't recognize political boundaries and that there needs to be cooperation throughout the lifecycle of a migratory bird in order for there to be success, if you will, or good management of that population.

A gull flies near the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, DC. (Photo: Victoria Pickering, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, I understand that the Migratory Bird Treaty Act began as a way to deal with the hunting of birds for their feathers and such, but in modern times it's been used in different ways, I understand related to the Exxon Valdez incident, for example, or the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling rig in 2010. How was that law used to protect birds in those instances?

SCHMIDT: In those instances where there was negligence or gross negligence and the spilling of oil that ended up killing thousands of birds, it was used in a punitive manner to fine the companies responsible for those actions, in this case BP and contractors associated with that spill, and of course the Exxon Valdez back in 1989 when that disaster occurred in Alaska.

CURWOOD: And now how has Secretary Zinke chose to interpret this law and what's your objection? I gather the oil companies don't much like this among other folks.

SCHMIDT: Well, Secretary Zinke and his Department of Interior have interpreted it in a way to really narrow the use of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Heretofore for decades - hence the 17 signatories to that letter, back to the Nixon administration, are objecting to this narrow view where someone is only violating the law if they intentionally and purposefully killed or took that bird. It wouldn't, for instance, be able to be used as a tool in conservation as it has been for decades to prevent such things as oil spills or mass electrocutions on electric wires and power lines, wind turbines, oil pits. And in the examples that we already talked about in terms of Exxon or BP, it certainly wasn't any intention on the part of those companies to take or kill those thousands of birds. But it happened,s and it happened as a result of some negligence or improper behaviors in some fashion. So, that use of the MBTA has been eliminated now with this new interpretation that is precedent-setting, frankly, and goes against all Republican and Democratic interpretations over the past 40-plus years.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the oil pits. What exactly are the oil pits that this law used to protect birds from and how difficult is it to make these oil pits safe for birds?

Geese convene at Waneka Lake in Lafayette, Colorado. Paul says one of the biggest threats to migratory birds is habitat destruction. (Photo: Let Ideas Compete, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

SCHMIDT: Well, in the process of developing oil and bringing it to the surface there are waste pit areas around those wells that are used to store oil, and they become an attraction to birds that are flying overhead. They don't recognize that that's a toxic material. They will view it, frankly, as a watering hole and immediately fly down and become -- the chemical exposure, they end up dying. It was recognized that that was a fairly significant problem particularly in some parts of the west 20 years ago. And therefore technologies were developed, techniques whereby you put a netting over that oil in order to keep the birds from committing suicide, if you will, inside an oil pit.

CURWOOD: What legal challenges, if any, are being mounted to oppose the Trump administration's interpretation of this law?

SCHMIDT: I don't know currently of any legal challenges right now. It's early in the process. It's only a couple of weeks old. Interesting enough, in the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, there is no civil suit provision. In other words the author allows civilians to bring suit against the government for not enforcing the law, if you will, unlike some others like the Endangered Species Act which does have a provision that allows for organizations or individuals to take issue through the courts.

CURWOOD: I imagine that Canada or Mexico or other nations who are parties to the Migratory Bird Treaty might have standing to bring a complaint.

SCHMIDT: Of course they do and, in fact, I understand that the Canadians are considering exchanging a diplomatic note with the United States expressing their concerns because it was just a few years ago when I was serving in the US Fish and Wildlife Service that we exchanged diplomatic notes relative to the Migratory Bird Treaty with Canada affirming both countries interpretation, and it's ironic that now Canada would have to come back to us and express concern or objection for a brand new interpretation that violates that diplomatic note that was exchanged between our State Department and the Foreign Affairs Office in Canada.

CURWOOD: So, how important is this Migratory Bird Treaty Act?

SCHMIDT: Well, for some of the takings that occur out there, there aren't any substantial protections if this is removed. Frankly, it was one of the first environmental laws, conservation laws on the books, that gave us sort of the road forward for conservation. And it's kind of a shame that we would roll it back after 100 years of success to where it will be narrowly interpreted and potentially cause more migratory birds to end up on things like the Endangered Species List.

A Common Loon with a chick in the state of Maine. (Photo: Fyn Kynd, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And of course, Paul, in your role as the Fish and Wildlife Service assistant director for migratory birds you were even-handed, but on a personal level what's your favorite bird?

SCHMIDT: [LAUGHS] Well, Steve, one of my favorite birds is the common loon. It is a mystical bird particularly where I grew up enjoying some summers, and that bird and the sound it makes -- a lonely sound [SOUNDS OF LOON CALLING] on a clear Maine lake -- is something very, very special. It holds a special place in my heart.

[LOON CALLING]

CURWOOD: Paul Schmidt is a former Fish and Wildlife Service Assistant Director for Migratory Birds. Paul, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SCHMIDT: I've enjoyed speaking with you, Steve, and good luck to you.

Related links:

- The Washington Post: “17 former wildlife officials urge Interior to rethink easing rules against killing birds”

- The letter drafted by Paul Schmidt and his colleagues

- The Migratory Bird Treaty Act

- More on the conservation rollbacks from Zinke’s Interior Department

Beyond the Headlines

The Northern Spotted Owl, an already threatened species, is facing a growing risk to its health from marijuana farms where the spraying of rodenticides is contaminating the owls’ food. (Photo: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let’s take a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s an editor with DailyClimate dot org and Environmental Health News, EHN dot org and he’s on the line from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey Peter, what’s up?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. Let’s talk about two animals with cute, cuddly reputations in pop culture – owls and pandas – that you probably wouldn’t want to get too close to in real life. And, unlike a TV ad or a Pixar movie, real life isn’t always that adorable.

CURWOOD: You’re telling me there’s not a happy ending?

DYKSTRA: For now, no. But let’s start with the owls. Recent research shows marijuana can be deadly for some spotted owls.

CURWOOD: Northern Spotted Owls, once threatened by chainsaws, are now threatened by a simple buzz?

DYKSTRA: In a way, yeah. Even as recreational marijuana use becomes legal in states like California, much marijuana farming remains unregulated and in many ways, an environmental mess. One of those ways is that rats and mice love hanging out at pot farms, so pot farmers often use rodenticides. Spotted owls and barred owls love mice and rats, and recent research shows they’re becoming unintended victims of the pot farmers’ poisons.

CURWOOD: But even without the poisons, the Northern Spotted Owl is still under threat, right?

DYKSTRA: That’s correct Steve, they’re not out of the woods.

CURWOOD: Ooh, well I think we should just fly right past such an awful pun and move on to the pandas.

Giant Pandas were recently updated by the IUCN from “endangered” to “threatened,” but they continue to face environmental dangers from damaged habitat and rapid industrialization. (Photo: Adrien Sifre, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND-2.0)

DYKSTRA: Sure, and sorry about the bad pun. In late 2016, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature delivered some good news on Giant Pandas, upgrading them from “endangered” to the slightly less dire “vulnerable.” But new research says not so fast. Not only is dwindling, fragmented habitat still an issue, but China’s rapid industrialization leaves its pandas open to toxic chemicals in the air and in food sources. And this will make the panda’s road to recovery even tougher.

CURWOOD: So pandas are suffering the same kind of pollution problems as many Chinese people, huh? Perhaps polluted pandas will be the same kind of iconic symbol for China that the flaming Cuyahoga River once was for water pollution in this country.

DYKSTRA: Well I guess anything is possible. And for this week’s history lesson, let’s take a look back at an American environmental giant of the 20th Century. William O. Douglas was pretty clearly the only treehugger to sit on the United States Supreme Court. He died 38 years ago this week. While on the bench in 1972, he argued that nature should have the same legal rights as humans.

Justice William O. Douglas was arguably the only “tree hugger” ever to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court. (Photo: Harris & Ewing from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division, public domain)

CURWOOD: Now that’s an idea that’s gaining increasing traction nowadays; but I don’t think it was enshrined into law when Justice Douglas was on the high court.

DYKSTRA: Nope, but get this: also while on the bench in 1967, Justice Douglas led a “protest hike” along one of the prettiest stretches of the Delaware River, on the Jersey side, to oppose the Tocks Island Dam.

CURWOOD: And the marching jurist got the Dam project stopped?

DYKSTRA: Well, the judge’s activism certainly didn’t hurt, but the prospect of the Tocks Island Dam inspired a major citizen’s movement, and today the area is a free-flowing river and part of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation area.

CURWOOD: Yeah and I understand that nearly four million visitors go there every year since it’s less than two hours from New York City.

Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Thanks Peter, we’ll talk to you again real soon

DYKSTRA: Ok Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories on our website: loe.org.

Related links:

- Live Science: “Owls Dying Near Marijuana Farms (Here’s Why)”

- The Revelator Project: “Don’t Believe the Hype: Giant Pandas Are Still Endangered”

- William O. Douglas biography

[MUSIC: James King, “Jerusalem Tomorrow” on Gardens In the Sky: The Bluegrass Gospel of James King, composed by David Olney, Rounder Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, Counting crows – and ducks, and hawks and chickadees, and a multitude of other birds. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, don’t fly away!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Canadian Brass, “The Toy Trumpet” on Noel, composed by Raymond Scott, RCA Victor]

Making a Bird List and Checking It Twice

Teenage birders Ryan Andrews, B.J. Dooley, and Max Liebowitz, from left to right. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. In the natural world that surrounds us, even in cities, birds can be found almost anywhere, from noisy crows squawking in a park to pigeons pecking around on the ground. And every Christmas for over a century, there’s been a yearly bird count, an occasion for bird lovers and citizen scientists to head outside to take note of these creatures sharing our world. And in the last days of 2017, they included Living on Earth’s own Jenni Doering who joined the count in Oceanside, California.

[HIGHWAY SOUND]

DOERING: On a Saturday morning two days before Christmas, the freeways of north San Diego County hum with a constant flow of shoppers on a last-minute search for that perfect gift, or travelers on a long haul to visit family for the holiday.

[FREEWAY SOUND, BIRDSONG: DUCKS, CINNAMON TEAL CALLING & TAKING FLIGHT]

DOERING2: But at an overlook for a saltwater lagoon in Oceanside, among the rush of traffic, two people listen closely for sweeter sounds and peer through powerful binoculars.

[BIRD SONG: DUCKS, CINNAMON TEAL CALLING & TAKING FLIGHT]

DOERING: They’re birdwatchers, drawn to the Agua Hedionda Lagoon Ecological Reserve by the many birds that live here or visit on long migrations.

NELL: Hi, I’m Gretchen Nell.

MORROW: I’m Andy Morrow, with Buena Vista Audubon Society.

DOERING: Gretchen is petite and bespectacled; Andy is solidly built, and both are dressed in layers for the morning chill.

MORROW: So our objective this morning is to go through our territory, visit all the different types of habitat that we can find, and tally all the different bird species as well as the individual number of birds within each of those species.

Agua Hedionda Lagoon. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: They’re taking part in the Christmas Bird Count, and though all they do is count birds, Andy Morrow says the Christmas Bird Count sprang from rather violent origins.

MORROW: Before the 1900s, the common thing to do was to go out on a Christmas bird hunt and shoot as many birds as you could, and then you would gather together and count up the number of birds that you’d killed and see who was the winner. And that did not sit well with some of the people that were more interested in the birds themselves.

DOERING: So, in 1900, a member of the fledgling Audubon Society organized the first Christmas Bird Count.

Today, some of the most prolific counts are in Southern California, thanks to the famously mild winter weather and the diversity of ecosystems here. Gretchen Nell squints through her binoculars at the salt marsh below.

NELL: Northern Harrier, flying left to right. And it’s causing -- oh everything’s ‘lifting’ because the Northern Harrier’s flying, those are all willets, wait no, those are all ducks, excuse me, I saw the white.

Andy Morrow is an avid birder and a former Oceanside Christmas Bird Count coordinator. (Photo: courtesy of Andy Morrow)

MORROW: So the Northern Harrier is called a marsh hawk, also, and you can see it right now in front of us, the way it glides along just above the surface of the marsh. And it is trying to scare up either birds or more likely rodents that it can prey upon.

DOERING: Nearby, two people on paddleboards glide up a channel between marsh grasses.

MORROW: From our perspective, keeping an eye on them as they go along that channel might be productive, because they’re gonna scare up a few birds that otherwise would be sitting down there, and maybe we’ll see them in flight.

NELL: Just like the harrier did.

MORROW: Right.

The Northern harrier, also known as a marsh hawk. (Photo: Don DeBold, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

NELL: So we have helpers that we hadn’t anticipated.

[TRAFFIC NOISE]

DOERING: This refuge, like most in Southern California, is an expanse of undeveloped land and water surrounded by a sprawling city, and it’s bisected by buzzing high-voltage power lines.

[BUZZING OF POWERLINES]

MORROW: We can never totally escape civilization when we’re birding but yet you have these little moments of time when you do get out there in nature; it still exists right here in the middle of our community.

DOERING: In fact, the Christmas Bird Count seeks out birds in all environments – including highly urban ones.

[SOUNDS OF A PARKING LOT]

ANDREWS: Well, this is it: remarkably clean parking lot.

DOERING: In front of a grocery store not far from the lagoon where Andy and Gretchen are making their count, three teenage birders document the pigeons, gulls and crows that like to forage here.

LIEBOWITZ: I’m Max Liebowitz – 19 years old.

DOOLEY: B.J. Dooley, I’m 16.

ANDREWS: Ryan Andrews, and I’m 18. [BRIEF PAUSE] On a normal day no birder would ever come to like this parking lot because it’s literally just a parking lot. [LAUGHS] But sometimes you get Brewer’s blackbirds; or some other things that you won’t often get in other places. Like, Brewer’s blackbirds, I’ve had people joke that the most reliable place for them is a McDonald’s parking lot. There are some species that like trash, basically. [LAUGHS] And so you have to go where there’s trash.

Gretchen Nell is a retired University of California, San Diego professor. (Photo: courtesy of Gretchen Nell)

DOERING: He can trace his passion for birding to a white elephant gift exchange, the Christmas when he was seven years old.

ANDREWS: We brought a bird feeder, we were hoping not to get it, and we end up getting it. [LAUGHS] So we’re like, okay, that works. Um, and then, it’s like just in our basement – and then finally we put it up, and this is actually when I lived in Missouri and we were part of like a youth organization that the Missouri Conservation Department runs, and they asked us to count bird species that come to our feeder. So I started doing that and then when like the time period we were supposed to do that ended, I just didn’t stop. I just kept on counting birds and looking in my yard and then it kinda just spiraled out from there. By like 2013 I was like, I just was birding constantly. So, been hooked since! [LAUGHS]

DOERING: Ryan’s found lots of rare birds over the years – and though it’s also rare to find a teenage birder in basketball shorts and a hoodie, he says if you know where to look, there are plenty of young birders.

ANDREWS: I think that technology has helped with that; in past 5-10 years there’s been like a massive increase in number of young birders. Most of us like meet online in different forums; we have a young birder chat with like probably only like 100 members, ish, but that’s still like 100 members and we’re from all over the country and a few people from like Australia and Singapore and stuff.

DOERING: They connect through the most popular birding app, e-Bird, where they can submit checklists. Social media plays a big role in sharing their successes with each other, too.

ANDREWS: Like, I mean we’re all teenagers so Instagram, Snapchat, those types of things are big. [LAUGHS] A lot of people are on Facebook which I’m not, which makes me sad a lot of the times ’cause like all the good rare bird alerts for like the country are on Facebook.

DOERING: Ryan, B.J. and Max want to cover more territory, so we head to the beach, just a mile away.

[SOUND OF CAR DOOR, AND DRIVING, THEN WAVES ]

DOERING: The sand is soft, almost silky where it’s dry high on the beach, and warm with the midday sun. Small shorebirds called sanderlings chase the water as it pulls back out to sea, then run away as it slides back up the beach. Every bird counts in the Christmas Bird Count; even common species like gulls. Zooming in 60 times through his spotting scope, Ryan locates a big flock floating just beyond the surf.

ANDREWS: Ok so these gulls are … pretty much entirely California. [COUNTING] 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16… 34, 36, 38…nine… ten. ok. 63 64. There’s 64 California gulls.

DOERING: Pelicans soar overhead with their huge beaks and loose throat pouches; beyond the waves, dolphins gambol in the Pacific, a nice surprise dividend after peering at the horizon all morning, looking for birds. It is hard work, though fun; most teams are out in the field by 5:30 a.m. and stay till after noon.

[BACKGROUND CHATTER]

DOERING: But when the one hundred or so birders from the Oceanside Bird Count all gather at the local nature center to compile their lists and quell their hunger with a hearty lunch of chili, the excitement is palpable.

High-voltage power lines run across the Agua Hedionda Lagoon Ecological Reserve (Photo: Jenni Doering)

[BACKGROUND CHATTER]

DOERING: One of the leaders of the flock calls the room to order.

[KNOCKING ON WOOD]

MAN: I know we don’t want to be here ALL afternoon.

DOERING: Andy Morrow steps up to the podium to officiate the count.

MORROW: All right! This is… what is this, this is the 118th Audubon Christmas Bird Count. And the Oceanside count has been in business since 1955. And that particular count, I think we had 117 species, 8 birders went out and did it.

[AUDIENCE MURMURING, “WOW”]

MORROW: And just for the heck of it I looked at that count and there were 54 loggerhead shrikes seen on that one.

[AUDIENCE EXCLAIMS: WOW!]

MORROW: Those were the days, when we had loggerhead shrikes.

DOERING: Andy starts going down the list and the birders call out whether they’d seen that species today.

MORROW: Double-crested cormorant.

AUDIENCE: Yes.

MORROW: Pelagic cormorant.

MORROW: Osprey.

AUDIENCE: Yes.

MORROW: White tailed kite.

AUDIENCE: Yes.

MORROW: Good. Northern Harrier.

AUDIENCE: Yes.

MORROW: Wilson’s snipe.

AUDIENCE: Yes!

MORROW: Yeah!! [LAUGHS] Where did you see it, Suzy? Right here?...

SUZY: Yep! It’s ours.

MORROW: -- in our lagoon.

SUZY: Right here in the lagoon. [LAUGHS]

DOERING: It takes several minutes to run through the whole list, and at last, Andy counts them all up.

MORROW: All right – our preliminary count total for the 2017 Oceanside Christmas Bird Count is [DRUMROLL ON THE WOODEN PODIUM] … 181 species.

[CHEERS, APPLAUSE]

Caspian Terns were at record or near record lows in this year’s Oceanside Christmas Bird Count. (Photo: Bryce Bradford, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: The final count – which included the results from a team that was still out on the ocean counting birds – recorded 193 species, not far from the record of 200 set several years ago. Perhaps even more impressive was the sheer number of birds the 115 birders recorded: thirty-five thousand that day. But several species were at record or near record lows this year: Forster’s Tern, Caspian Tern, the Greater Yellowlegs, and the Loggerhead Shrike. Habitat loss and climate change are largely to blame, says Andy Morrow.

MORROW: Certain birds are retracting and abandoning certain areas because they no longer have the resources any more that they used to because the climate has changed for them.

DOERING: Yet that change means that other species appear to be thriving: the Great Horned Owl, the Merlin, Hutton’s Vireo, and the Acorn Woodpecker. And the birds that once were shot on Christmas, now instead help tell a story of a changing world. The sharp eyes and keen ears of birdwatchers everywhere help translate their flights, calls and songs into actionable data that will be instrumental for the scientists and decision-makers who hold the future of the environment in their hands.

For Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering in Oceanside, California.

Related links:

- About the Christmas Bird Count

- Bird sounds thanks to the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- eBird, a popular online birding community

[MUSIC: The Canadian Brass, “The Toy Trumpet” on Noel, composed by Raymond Scott, RCA Victor]

Babysitting Arctic Terns

Arctic Tern in its nest. (Photo: Nathan Graff / USFWS, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[CALLS OF ARCTIC TERNS]

CURWOOD: In the Christmas Bird Count, it’s not just the local resident species that are tallied, but the birds of passage too. So if you happen to live in the right latitude, you might get to add in the arctic tern. They’re rather ordinary black and white shore birds, with bright red beaks. But they are champions of migration. In fact Arctic terns travel as much as 56,000 miles a year, which is the longest known migration on earth. To give them some help conservationists work hard to protect part of their breeding habitat on the east coast of England, just south of Scotland. Here to tell us more is Gwen Potter, she’s the Countryside Manager for Northumberland Coast and Farne Islands at the National Trust, a conservation organization.

National Trust purchased more than two hundred acres of shoreline to protect habitat for breeding Arctic terns. (Photo: Kate Bradshaw)

POTTER: They are the most graceful birds you could ever imagine. So, they have this incredible white and gray color and they just kind of float through the sky and twist, and in the start of the breeding season, they like to play with each other in the sky, and they'll fight each other off, and they have these beautiful forked tails as well. So, they're quite often called sea swallows, and they’re just the most wonderful birds to see. And they're very, very angry, Arctic terns. They like to attack people when they - when people approach their nests. So, they've got a lot of character as well.

CURWOOD: Your organization has bought up some 200 acres of land to protect that breeding habitat for them, and you have sort of set up a round the clock babysitting service for them. Why and what did that entail?

POTTER: We already have an area of land that we look after for these terns, and we now have a bigger area that we can protect which is absolutely fantastic. So, we've basically doubled the area that these terns would potentially be nesting in. So, the idea will be to close off some of these areas in the summer months to allow those terns to come in and nest on the sand and that way we’ll be able to keep an eye on the them around the clock. We’ll be living in the dunes nearby, and we'll be checking up on them 24/7.

Arctic Tern eggs. (Photo: Mike Beauregard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, I understand in some of your protection of these birds, you actually end up relocating nests. How does that work?

POTTER: We do. When there is a very high tide, we move the nests onto fish boxes filled with sand, and that just raises them above that water level. It is something that is quite risky because obviously you think, I'm interfering with the nest, it might create an issue. But it's a tried and tested method. Eighty percent of the time it's successful and, ultimately, if we didn't do that, they would simply be washed away.

CURWOOD: So, what are the risks to the terns there as they are nesting?

POTTER: In the daytime, it's generally humans, people. So, if people walk through and they don't see the eggs, and they don't really know where they're going, they can cause a lot of disturbance. If they get too close, quite often they'll get attacked by the birds, so they'll very quickly realize that they're not supposed to be there. It's quite scary for them, but in the meantime, what will happen is the birds will be off their nests all of the time, and then they're leaving their eggs behind. Their eggs will chill, and they won't survive. In the night time, it tends to be predators coming in, so we'll have all kinds of different species that will come in and try and take eggs and then they'll try taking the younger chicks. We do have one more risk, which is people actually stealing eggs.

CURWOOD: People stealing tern eggs? Why?

POTTER: So, it's something that people used to do in Victorian times, they just used to collect eggs, and it's a bit like stamp collecting. And there are people who for very, very rare species will spend huge amounts of money on acquiring some of these rarer eggs.

CURWOOD: So, what are your results? How many terns were able to successfully breed there and how does that compare to previous years?

POTTER: We had a slightly higher number of Arctic tern pairs last year. But the number of fledglings that they produced, so the number of birds that successfully went on to become adults, went from two to 479. So, the previous year in 2016, it was two and then it's gone up by a very large number, which is fantastic news.

Arctic terns migrate from breeding grounds in the far north (red) to the Antarctic for summer in the southern hemisphere (blue). (Image: Andreas Trepte, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.5)

CURWOOD: Wow! So what do you attribute that to?

POTTER: In all honesty, it's weather. So, we do as much as we can to protect these birds, but quite often the weather can cause huge issues because they live on the tideline. If there are increased numbers of -- such as extreme tide, the eggs are washed out. And we had slightly better weather in most recent years. Over time what we have seen though is that we do have increasing numbers of really severe weather events that will impact on these nesting birds. So, we're looking but in the long term, we will have more extreme tides which can impact some of the time in localized areas as well.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, once those Arctic terns take off that's when their real work begins. Tell me a bit about their migration pattern.

POTTER: It's a most wonderful thing, yeah. They've got a bit of a job. They basically go to Antarctica from here in Northumberland, and when they reach Antarctica, they'll spend quite a lot of time essentially flying the southern oceans to Australia and New Zealand and back in between around Antarctica and right back up to exactly the same place where they originally nested. So, that's the equivalent of flying twice around the circumference of the globe. And they're seeing more daylight than any other bird because they're spending all of their, our winters down in the Antarctic where it's now sunlight almost 24 hours a day.

CURWOOD: So, among all these Arctic terns that buzz around the planet to the tune of nearly 60,000 miles a year, any one of those critters that’s attracted your attention for one reason or another?

POTTER: We do have a couple of birds that actually some of the terns kind of nest on the roots where we're actually going to move these boxes, so they will quite often attack you, particularly at the beginning of the season. They get very, very angry when you go past them. So, what they'll do is swoop down, they’ll peck on your head, they'll also poo on your head as well, and so those particular ... and they are the birds that come back every year. So we know number 23 is back, fantastic. You know what's going to happen when we go down and look at the boxes! [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Number 23 is apparently full of it, huh?

POTTER: [LAUGHS] That's right.

CURWOOD: Gwen Potter is the Countryside Manager for the Northumberland Coast and Farne Islands at the National Trust which is a British conservation organization. Gwen, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

POTTER: Oh, thank you it was really good to talk to you. Thank you.

Related links:

- About the Arctic Tern from The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds

- National Trust

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988. That’s 800-218-9988. Our e-mail address is comments at loe dot org. That’s comments at loe dot org. And visit our web page at loe dot org. That's loe dot org.

[MUSIC: Simon and Garfunkel, “El Condor Pasa” on Greatest Hits (Originally on “Bridge Over Troubled Water”), composed by P.Simon/J.Milchberg/D.A.Robles, Columbia/Legacy]

CURWOOD: Coming up, a best-selling novelist and his passion for birds. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Lionel Hampton, “A Taste Of Honey” on Flying Home, composed by Robby Scott/Ric Marlow, LRC Jazz Classics]

Year of the Bird

Australia’s superb lyrebird is a masterful mimic. To attract a mate, a male riffs on the calls of other birds in the forest while shaking its splendid tail feathers overhead. Captive birds have been recorded aping the sounds of chain saws, car alarms, and camera shutters. (Photo: Joel Sartore / National Geographic Photo Ark)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[LYREBIRD MAKING INDUSTRIAL SOUNDS – HAMMER, SAW, DRILLING] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C0ZffIh0-NA

CURWOOD: That strange, rather industrial racket, is not, as you might imagine, a construction site but a Lyrebird, native to Australia, which spent time near a construction zone and learned to mimic the sounds it heard there.

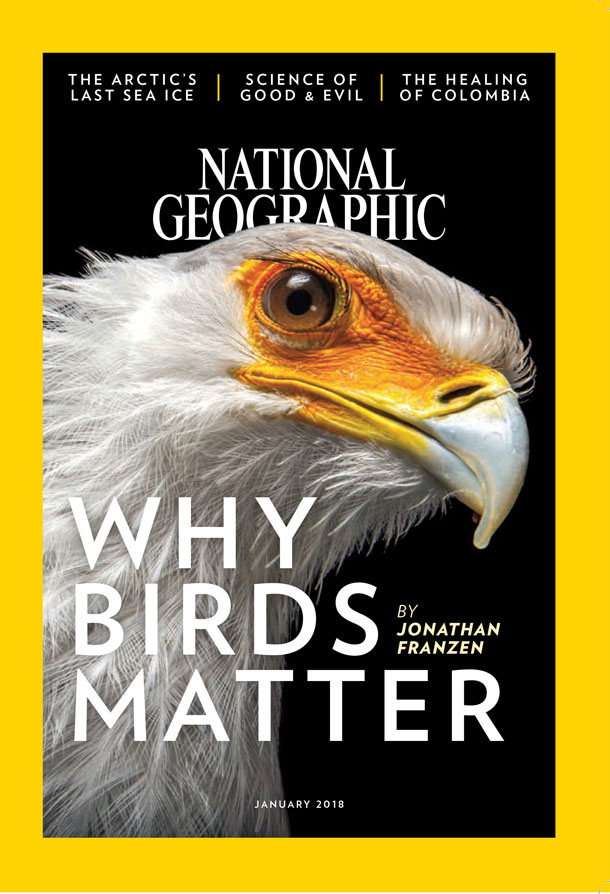

The Lyrebird is just one of nearly 10,000 species of birds living today and being celebrated in this year of the bird. As we mentioned earlier, National Geographic, along with Audubon and several other bird conservation organizations, have declared 2018 the Year of the Bird, in celebration of the centennial of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Nat Geo will feature stories about birds for the rest of the year. The January cover story, “Why Birds Matter,” was written by National Geographic writer and novelist Jonathan Franzen, who joins me now from Santa Cruz, California. Welcome to Living on Earth!

FRANZEN: It's great to be here. Thanks.

CURWOOD: So, tell me a bit about the Migratory Bird Treaty Act that's being celebrated this year. Why was it necessary back in 1918, and what does it do today?

FRANZEN: You know, when Europeans first came to North America, they were overwhelmed by the sheer quantity, not to mention the diversity of birds in North America. The sky going black with Passenger pigeons, just unbelievable richness of birds. Around the end of the 19th century suddenly people noticed, Uh–oh, the birds are gone. And in fact, the Passenger pigeon, Carolina parakeet, extinct. Egrets were on the verge of extinction because of the fashion in collecting them for their feathers. And so suddenly in the space of about 20 years, right around the same time that Teddy Roosevelt and others were advocating for a national park system, we had the invention of bird conservation. This saw the creation of the Audubon Society, and then it also - the capstone for all of that was the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

CURWOOD: So, what exactly is this Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and who is it a treaty with?

The January 2018 cover of National Geographic. (Photo: National Geographic)

FRANZEN: It's a treaty with Canada and Mexico, and it recognized that a lot of the birds we consider our own are actually shared with other countries. Now, of course, in the US, it's not just Canada and Mexico, it's all of South America where many of our migrants go, but these are our near neighbors and it was understood we as a nation have an obligation not to kill Canada's birds and vice versa, and the same thing for Mexico. So, basically there was a treaty signed, we won't kill each other's birds. And then there had to be a law to enforce that treaty, which basically made it illegal to kill any migratory bird except one of the huntable species, which is to say all songbirds. You couldn't kill a songbird in the US without breaking the law.

CURWOOD: Indeed. By the way, Jonathan, I have to ask, are you a birder? Would you consider yourself a birder?

FRANZEN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, I'm a bit of a birder. You know, it was migration that got me into birds. I've been a very urban creature. I was a New York person, lived in Manhattan and I had a then new girlfriend whose sister and brother-in-law were birders and they came down to see us in Manhattan and said, "Let's go birding in Central Park." And I thought -- I walked in Central Park every day. I've been walking in Central Park for years. I knew it like the back of my hand. They stuck binoculars in my hand. We walked out there and they started pointing things out, like, "Here's a warbler in a tree." I'm hearing a warbler. "That's a Northern Parula. Take a look at that." And I look up and here's this you know little three-and-a-half inch, four inch, long bird with this bright egg-yolk colored throat and this slaty back and cool eye patterns and it's like, "What is that?"

And for the next four hours it was a series of “are you kidding me?” We saw maybe 60, 70 species of birds in one afternoon. It was a brilliant May weekend and all the birds were coming through, and I had the sense I hadn't since high school when I realized what people were talking about when they talked about sex, like, oh, now I get it!

[CURWOOD LAUGHS]

FRANZEN: There was this huge hidden dimension to the world that was suddenly visible to me, and all I had to do to find out more about it was to go out by myself with binoculars.

CURWOOD: So, the title of your article in National Geographic is "Why Birds Matter". So, why do birds matter?

FRANZEN: [SIGHS.] Well, you can make a case that birds matter because they are valuable indicators of the health of natural systems, local ecosystems, larger ecosystems. If you go to an area that once was full of birds, and you can't find any birds, it probably means there's something very wrong with the ecosystem. That's a useful argument, although frankly you don't need birds to tell you when a forest has been cut down. You can also make an argument the birds matter because they do serve various economic functions. They do rodent and insect control. They are great pollinators. They are great seed distributors, but the basic fact is that birds are a net drag on our economy. They eat more than they give.

The Cerulean Warbler. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

[CURWOOD LAUGHS]

FRANZEN: Seriously! I mean, I actually -- I planted some blueberries behind our house knowing the birds would get them, but I thought maybe I'll get a cup or two of blueberries. No, every last blueberry gone. They're very good at that and I was fine because I actually like the mockingbird that had them. But -- no, so they will not pull their weight, and so if you're only metric is economic, you can't really make a good case for birds.

CURWOOD: Why do birds matter to you?

FRANZEN: So, birds are not just a vital part of nature, but they're a singular instance of nature because they have been world-dominating creatures for 65 million years. They are this brilliant adaptation of the original dinosaurs. They are feathered flying dinosaurs that managed to escape the big extinction event 65 million years ago and populate the entire world, and even now they are more widespread than any other kind of creature, including human beings. They're out in the middle of the most remote ocean, they're in the driest desert, they're in the middle of Antarctica in winter - not the middle, but the edge of that Antarctica in winter. If you care about the natural world that we came out of, you ought to respect these creatures that were the great thing that happened before human beings came along.

CURWOOD: Well, we're celebrating the centennial of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, so let's talk about some migratory birds. Jonathan, tell me about the Cerulean warbler.

FRANZEN: So, in North America, about half the birds that we have don't spend the whole year within our national boundaries, and especially many of the more colorful ones, including the Cerulean warbler, which is this tiny little bird, the male of which is bright blue, incredible little warbler. It typically will make a migratory journey of 5,000 miles or more in each direction. They like to winter in the cloud forest in northern South America. You can see them in Peru and Ecuador and then come spring they make their way - and again we're talking about a bird that weighs you know as much as a pencil or less - makes its way all the way back typically to West Virginia or New Jersey. And in the case of a particular Cerulean warbler that I heard about from a brother-in-law of mine, they're very rare in Massachusetts. There are only a couple of breeding pairs in all of Massachusetts, and so when you every spring go out to a location and you see a male Cerulean warbler in the same tree, you're - you've got a pretty good bet that that one bird has flown all the way to Peru and all the way back and found the same tree. And it may very well even like the same branch, and to me when you think of the tininess of that bird, the tininess of its brain, the fact that it managed to navigate through all of these hazards 6,000 miles south and then another 6,000 miles north and find the same tree again, it's just absolutely incredible to me.

With its massive bill and casque and a wing span approaching six feet, the great Hornbill is king of the jungle skies in Southeast Asia. It adorns its black and white feathers with a yellow-tinted oil secreted from a gland near its tail. (Photo Joel Sartore / National Geographic Photo Ark)

[CERULEAN WARBLER CHIRPING]

CURWOOD: Such a cool song that it has.

[CERULEAN WARBLER CHIRPING]

FRANZEN: Yeah, that's it. When you're walking down a road and you hear that you say, "Wow, it's a Cerulean Warbler!" They're actually rather hard to see because they like the canopy or the mid-canopy of trees that are leafing out, so you can hear it and it will drive you crazy for 20 minutes until you find it.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the dippers which have, should we say, a rather interesting way of getting around?

FRANZEN: Yeah, the old name for the dipper is the water ouzel, and it's a bird you find in the American west. It has a truly unique feeding style, it will fly from rock to rock, but in order to feed, it feeds on these aquatic insects and it essentially jumps in the water and walks on the bottom of this fast flowing stream picking up these little insects from the bottom of the stream, you know, and then it will pop out to catch its breath and then it will go back under. So, yeah, it's the strangest thing because it's like a small robin, it's this little thrush that you expect to be seeing in a front lawn or in a tree or something. No, it's actually disappearing for a minute at a time because it's walking on the bottom of the stream. It's incredible.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the European swifts. Now, they can stay aloft for nearly a year before coming back to land. How do they do that?

FRANZEN: Eating is easy because swifts basically catch insects in the air. Sleep...big problem, and the way swifts, we think, have solved it, it's difficult to actually monitor the brain activity of a swift that's flying 2,000 meters up continuously, but the best guess based on looking at other birds is that it has the capacity to sleep one half of its brain at a time, leaving the other...it's kind of like a plane with two pilots. One of them sleeps while the other one looks straight ahead and keeps the plane aloft. Again, it's speculative but there's really no other way to explain it because everything needs to sleep and how else could you stay aloft if you don't have that capacity?

California Towhee. (Photo: Cameron Rognan/Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

CURWOOD: Jonathan, what's your favorite bird?

FRANZEN: I love the California towhee, and I love it because it's so easy to overlook. Most people see this small to medium sized songbird hopping around on the ground, dull brown. It's everything that might turn a person off bird watching, and the towhee is a great bird because it's a bird you can see every day, it becomes a constant companion. When I was first getting into birds the towhee was the bird I was seeing every day- it’s probably beyond reason, but I formed this close, close bond with it. I thought, “Why this is a magnificent small creature that no one gives a second look to,” and the more I look at it the more beautiful I find it.

CURWOOD: Let's take a listen.

[TOWHEE CHIRPING]

FRANZEN: One of the many, many lovable qualities of towhees, is it's a relatively rare bird that mates for life, and once they have paired off the male and the female will sing duets to kind of announce to the world, we're paired up, no other comers need apply.

CURWOOD: What are the threats to birds these days?

FRANZEN: The biggest threat to birds and to wildlife in general is loss and fragmentation of habitat. And interestingly, kind of shockingly, the number one threat after habitat loss is outdoor cats. The reliable scientific estimates of the toll on North American birds, just US birds in a single year is phenomenal. It's on the order of one to three billion birds every year being taken by feral cats and free roaming cats.

After that, probably the next biggest worry is collisions. There's really nothing we can do about a lot of that. We've all had the experience of a robin or a flicker or something crashing into the kitchen window. There are things we can do to mitigate that. The toll is particularly high in cities that have skyscrapers whose lights attract birds. There are some very good initiatives going on to get cities to black out their high buildings during critical migration times, and the third major threat appears to be agriculture in general, but particularly the pesticides and it is worrisome that the new Environmental Protection Agency Director Scott Pruitt does not seem interested in rolling back some of these pesticides that had been studied and were about to be banned. But there's been a tremendous decline in birds that depend on open land, grassland birds and things like whippoorwills that feed on insects about open fields with the pesticides being the likely culprit for those declines.

CURWOOD: Wow, that sounds rather daunting. So, what can the average person listening now do to help birds?

Cerulean Warbler. (Photo: Bill Dyer/Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

FRANZEN: In a way it doesn't matter what you do as long as you do something. If all you do is pick up trash or help build predator proof fences down at the local Audubon reserve or help remove invasive plants from a wetland or something, obviously contributing to just some of the organizations that have the have the resources to do larger scale conservation work at the level of landscape or even country, that's a great thing, and in a very practical way you can write your Congressman right now and say, "Don't mess with the Migratory Bird Treaty Act", which is where we started this hour talking about that amazing act which is under threat in the current Congress and it's also under threat by the Department of Interior which wants to basically defang that law and make it OK to kill birds without having paid any consequences. So, the worst thing is to just ignore it, because once you pay attention you might fall in love, and once you fall in love, then you have to do something.

CURWOOD: Jonathan Franzen wrote the January cover story for National Geographic, "Why Birds Matter". Jonathan, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

FRANZEN: It's been a pleasure. Thanks a lot, Steve.

Related links:

- National Geographic – Year of the Bird

- Audubon Society

- Cornell Ornithology Lab

BirdNote®: Help Screech-Owls Find Homes

Screech-Owlet in a nestbox. (Photo: Ashleigh Scully)

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: In this year of the bird, you might feel like lending them a hand yourself – and Michael Stein has a suggestion in today’s BirdNote®.

BirdNote®: Screech-Owls Are Looking for a Home

[Western Screech-Owl, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/109017, 0.06-.09]

STEIN: Looking for a project for a winter’s day? Consider giving screech-owls a helping hand. Eastern and Western Screech-Owls span the wooded areas of the continent, nesting in naturally occurring tree cavities left vacant by large woodpeckers. Such natural housing opportunities are often in short supply, though. And that’s where you come in – because screech-owls will happily take to nestboxes.

[Eastern Screech-Owl, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/107366, 0.06-.08]

STEIN: In fact, they’ll nest in Wood Duck boxes, flicker boxes, and even the occasional mailbox. But you can build an ideal home for them with a few pieces of wood, a saw, and an hour or two of your spare time.

Eastern Screech-Owlets inside a nestbox. (Photo: Hunter Desportes)

The owls like an area with ample trees, but they’ll also nest right next to your house. You’ll need to attach the box to a tree or post at least 10 feet above ground, which helps the owls sneak in and out. When leaving the box, an owl drops low to the ground and stays low in flight for some distance, to elude potential predators – like larger owls or raccoons.

Getting a nestbox up in January might seem too early, but in fact screech-owls start courting as early as February, with the male hooting near a potential nest site. So now is the ideal time to get started.

[Western Screech-Owl, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/109017, 0.06-.09] I’m Michael Stein.

[Eastern Screech-Owl, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/107366, 0.06-.08]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2005-2018 Tune In to Nature.org January 2018 Narrator: Michael Stein

And dive on over to our website, loe dot org for pictures.

Related link:

This story on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: “I Remember Clifford” on composed by Benny Golson (CITATION COMING)

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, rising seas threaten to leak into a covered nuclear waste pit in the remote Marshall Islands…

WILLACY: Unfortunately this is a nation where its nuclear legacy is colliding directly with the climate change future. And that dome is the intersection of all of that.

CURWOOD: The dilemmas of nuclear pollution, that's next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: “I Remember Clifford” on composed by Benny Golson (CITATION COMING)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth