Living on Earth

Air Date: Week of March 23, 2018

listen / download

Hurricane Harvey brought intense downpours to the Houston area in August 2017, precipitating severe flooding. (Photo: Tom Fitzpatrick / World Meteorological Organization, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s “patchwork quilt” of flood maps has coverage gaps, and is obsolete in places, according to a recent study by the EPA, Nature Conservancy and UK University of Bristol. The new study finds 40 million Americans are actually at risk from floods, rather than just the 13 million people who populate FEMA’s official flood zones. Kris Johnson of The Nature Conservancy tells host Steve Curwood that better maps could also save lives, homes and nature by discouraging development in flood-prone open spaces.

Transcript

CURWOOD From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. With all the extreme weather we’ve had lately, it seems important to know if one could get flooded out when hard rains fall and rivers rise. But if you rely on Federal Emergency Management Agency or FEMA flood maps, you could get false comfort.

New research using high tech analysis finds some 40 million Americans live in areas where there is a one percent risk of a flood in any year—a so-called hundred year flood--but FEMA flood maps indicate only 13 million or so face that risk. And the research team made up of folks from the UK University of Bristol, the U.S. EPA, and The Nature Conservancy, projects that by the middle of the century, 60 million Americans will be at risk of such floods, unless land use and planning change. Kris Johnson of the Nature Conservancy is a coauthor of this study. And Kris – this does not sound like good news for people who live near big rivers or even small streams.

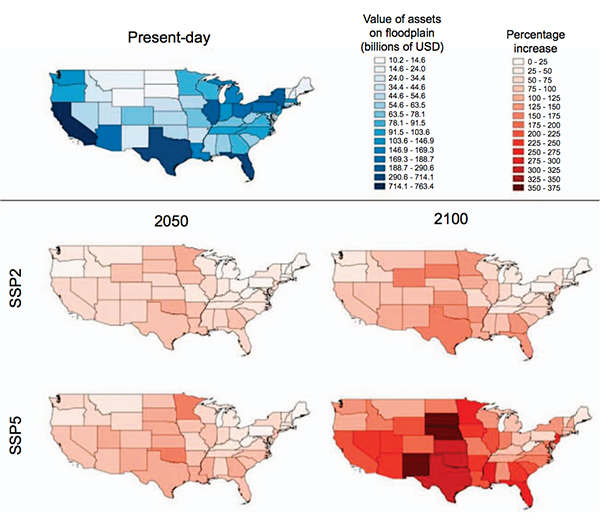

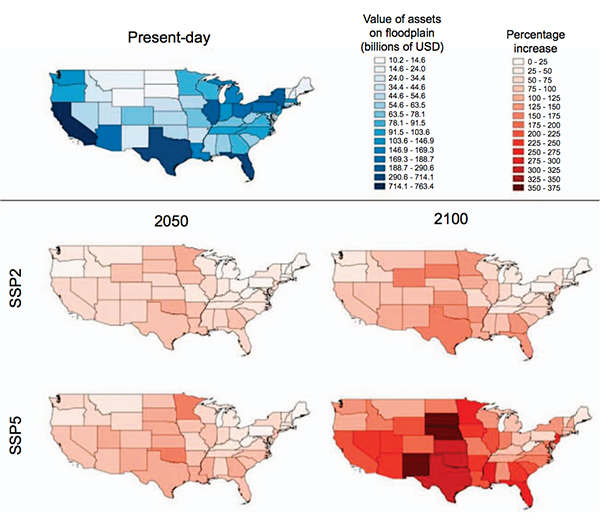

Maps depicting the value of assets within the 1 in 100 year floodplain, split by state. The ‘current’ map (blue) indicates the absolute value of assets within each state’s floodplain. The ‘future’ maps (red) indicate the proportional increase in exposed assets from the present-day to the respective year under a particular scenario. (Image: Fig. 4, “Estimates of present and future flood risk in the conterminous United States,” Oliver E J Wing et al 2018)

JOHNSON: Well, you're right. It's not good news that we find out that there's many more people, many more buildings, much more property in harm's way from flooding. But it is useful information, right? It's important that people know. It's important that we as a country have a much better picture of where the risk really is and how significant it is, and right now there is sort of a bright line, in-or-out approach to flood insurance.

There are FEMA maps, where they exist and where they're available. If your property is within this so-called 100-year flood plain – the boundaries of this one percent chance flood event, well then, if you have a federally-backed mortgage you need to buy flood insurance to protect yourself and your property. If you're not within that, if you're just on the other side of that line, well then you don't need to buy any insurance and you're essentially being told that you're not at any risk of flooding, which we know is not true. And so we need a more comprehensive and proactive and sort of integrated approach to thinking about risk because as our study shows, there are many many more people who are probably in harm's way than we had originally thought. We know right now that there are five-and-a-half trillion dollars worth of assets that are at risk from a -- what we call a one percent chance flood, or a 100-year flood. You know, We need to address that we need to mitigate that and more importantly we need to not put any more people or property or assets in harm's way in the years to come because that will only make that price tag even bigger.

CURWOOD: Kris, what got you and the Nature Conservancy interested in studying flood mapping?

JOHNSON: Yeah, well that's a great question. You know, we focus heavily on conservation, but we're also really interested in how conservation and protection of open spaces can not only provide benefits to nature, but can also provide benefits to people, and studying rivers and river management and flood plains over the years, what we came to understand is that there's actually a pretty exciting sort of win-win opportunity in flood plains, and that is that if we protect and restore these places that are ecologically and hydrologically really important – they provide habitat for birds, they support spawning of fish, they store carbon and they help reduce flood risk – so we can protect these places that provide these environmental benefits and at the same time we can actually help reduce the impacts, you know, to people and to property.

CURWOOD: And so, what was the moment that you decided or your organization’s decided, hey, we really ought to figure out what's going on with these flood maps?

JOHNSON: Well, we tend to think big picture. You know, when you're grappling with sort of complex environmental challenges, you don't just look at one particular place on a map. You think about sort of regions and ecosystems and watersheds, and what we discovered is that the history of flood risk management has very logically gone sort of place by place and piece by piece. That's really kind of a function of how our science, our modeling, our engineering approach to understanding flooding has evolved, and it is also is sort of a function of our institutions, our local units of government, and the way in which they manage flood risk. And the problem with that is that here we are in 2018 and we have essentially kind of a patchwork quilt of flood risk information for our country.

There are places where we have, you know, very good, very detailed up to date information about where we think flooding is most likely to happen, but there are also many places in this country where we have no mapping at all, or you know, there may be towns and local municipalities that are still managing their flood risk off of paper maps that were drawn up 20, 30, 40 years ago. And so from the Nature Conservancy's point of view, this new modeling approach really gave us the ability to develop these floodplain maps at a much bigger scale, which helps us think about risk and it also helps us think about managing the environment in a more integrated way.

Rivers are naturally dynamic, meandering back and forth across a landscape. In the above satellite image, the small, blocky shapes of towns, fields, and pastures surround the graceful swirls and whorls of the Mississippi River, the largest river system in North America. Countless oxbow lakes and cutoffs accompany the meandering river south of Memphis, Tennessee, on the border between Arkansas and Mississippi. (Photo: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/USGS)

CURWOOD: Now, as we mentioned at the beginning of the segment, your study findings would indicate that there are millions of homeowners and commercial building owners out there that don't understand that their at risk from flooding because the FEMA mapping hasn't shown them to be. So, what can those folks who are concerned do to find out whether in fact they are at risk?

JOHNSON: I would say for any sort of, kind of aware and proactive and concerned property owner or homeowner, take a look at your local city and town and find out, you know, what the floodplain maps show for your area and find out when the flood map was created, and try to understand how good the information is for your neck of the woods. In many cases, if you live in a large city the flood plain maps and the flood risk information is probably pretty good, but of course, we all know that risk is changing as more development happens, as climate change moves forward, flooding is becoming, you know, increasingly severe, increasingly significant. We don't fully understand all the ways in which that may change everywhere, but we know that this problem is only growing.

So, if you're near a floodplain, on the edge of a floodplain, if you're not sure, talk to your insurance agent, find out what policy options might be available for you. I mean, the good news is if you're not within a current FEMA flood zone, you could probably add a flood risk reduction part onto your policy for probably, you know, fairly little expense.

CURWOOD: Looking back over this last very wet season – the Harvey, the Maria, the Irma – how did your study’s findings compare with places that flooded out that frankly hadn't been expected to flood out?

JOHNSON: Well, one thing I should say is our study focused really on riverine flood risk – non-coastal flood risk – basically. Some of the flooding that we see in coastal areas due to storm surge, due to increasingly rising sea levels, that flooding isn't something that we tried to map or model with our study. But I will say that in a couple places, for example, in Houston, many of the areas that were inundated, that did get flooded during that events, they do show up on our maps as places that you might expect to be flooded during a big event.

CURWOOD: So, to what extent did you factor in potential climate change impacts in your analyses?

JOHNSON: As I mentioned earlier, we know that the climate is changing and we know that that change is going to have real implications for flooding, for rainfall and for impacts on people. We also know, unfortunately, that it's going to be really varied from place to place. Some parts of the country are likely going to get wetter and more intensely impacted by flooding, whereas other places, you know, we may actually see risk from this kind of flooding diminish over time.

Texas National Guard soldiers aid citizens in flooded Houston, Texas in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, August 2017. (Photo: Lt. Zachary West, 100th MPAD / Texas Military Department, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

So, our current study doesn't incorporate that. That would be sort of coming down the road hopefully for us scientifically. So, what we did instead is we used our current understanding of where flood risk is and then we looked ahead at where the Environmental Protection Agency thinks that people might continue to move and develop property, and so we know that even if flooding doesn't change from what it is today, in 2018, we know that people are unfortunately going to continue to develop in harm's way and we project by 2050, there will be you know, upwards of about 60 million people at risk from a one percent chance flood event, a 100-hundred year flood event in the U.S.

CURWOOD: And so those 60 million people, you project would be living in relatively high flood risk areas you make that projection without including climate disruption, you make that projection not including possible storm surges in coastal areas.

JOHNSON: That's right, that’s right.

CURWOOD: So, at the end of the day, the risk would be maybe not quantifiable but larger really than what you're saying.

JOHNSON: I think that's right, I think that's right. And the other thing to keep in mind is that, of course, if people do develop in these areas, typically as a society we feel some understandable obligation to protect them against floods, and so that in turn would mean potentially building more levees, building more flood walls, more flood defenses, which of course cost taxpayer money and not only that but when you defend a particular place against a flood event, you push the water downstream faster, essentially. And so you can likely exacerbate flooding somewhere else in the system if you're really defending a particular place against a flood. And so, how we respond to this increased flood risk, how we respond to increased development, that may make the problem even worse in some places.

Kris Johnson is an Associate Director for Science and Planning for The Nature Conservancy’s North America Agriculture Program. (Photo: The Nature Conservancy)

CURWOOD: Because what you described happened after the huge floods along the Mississippi in the 1920s a century ago, they built all these levees and that just moved the water downstream at a faster velocity, where people further south now get pretty serious flooding.

JOHNSON: That's exactly right and you know, you would think we would have more fully learned our lesson in the 100 years since those big events. You know, rivers need – they need room to roam. Big events come and they move from side to side and we need to sort of resist the temptation to farm right up to the banks or to put our houses and buildings right up to the banks because sooner or later an event, you know, is going to happen and that's going to put those properties in at risk.

CURWOOD: So Chris, how much undeveloped space is there still along waterways?

JOHNSON: Well, you know, we're still finishing up some analysis in another paper that will really quantify that, but looking across the U.S., across all of our rivers and streams, initial estimates are something on the order of about 800,000 square kilometers of open space in flood plains that could someday potentially be developed. It's certainly not all going to be developed, but these are places where we should really look hard and consider, you know, some protections, some zoning, some better planning, to make sure we don't develop in these places and don't increase risk to people or property.

CURWOOD: Kris Johnson is an Associate Director for Science and Planning at the Nature Conservancy. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today Chris.

JOHNSON: Thank you.

Links

http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aaac65/pdf - The study in Environmental Research Letters: “Estimates of present and future flood risk in the conterminous United States”

https://www.citylab.com/environment/2018/03/new-report-says-fema-badly-underestimates-flood-risk/554627/ - CityLab: “New Report Says FEMA Badly Underestimates Flood Risk”

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-03-15/fema-strips-mention-of-climate-change-from-its-strategic-plan - Bloomberg: “FEMA Strips Mention of ‘Climate Change’ From Its Strategic Plan”

https://msc.fema.gov/portal/search - FEMA Flood Map Service Center

https://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/urgentissues/land-conservation/global-agriculture/north-america-agriculture-kris-johnson.xml - Kris Johnson’s The Nature Conservancy profile