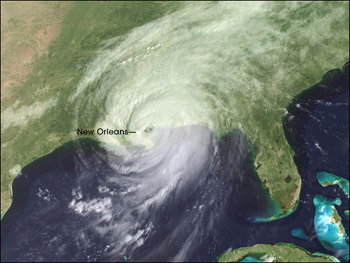

Official Calls Environmental Damage From Hurricane Katrina "A Crisis Waiting to Happen"

Air Date: Week of September 2, 2005

A man carries a baby through the flooded streets of New Orleans. (Photo: Photographer's Mate Airman Jeremy L. Grisham, U.S. Navy)

In the wake of one of the largest natural disasters in U.S, history, New Orleans is scrambling to provide essentials for its survivors. The larger task of reconstruction and remediation looms, and analysts say Katrina's long-term effects will last for decades. Living on Earth's Jeff Young talks with Hugh Kaufman, a senior policy analyst for the EPA, who says the city's construction and lack of environmental enforcement made the storm's damage worse than it could have been. Meanwhile, workers at Louisiana's Department of Environmental Quality are surveying the area for chemical contamination, and guest host Bruce Gellerman talks with DEQ's Chris Roberie about their findings. Also, a page from history: New Orleans Times-Picayune reporter Mark Schleifstein remembers the aftermath of Hurricane Betsy in 1965, and a lesson on how not to rebuild.

Transcript

GELLERMAN: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studio in Somerville, Massachusetts, it's Living on Earth. I'm Bruce Gellerman, sitting in for Steve Curwood.

Words simply fail - even pictures can’t convey what it must be like in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. How do you rebuild an entire city, let alone the lives of so many people? And how do you even begin to deal with the long-term environmental consequences? Well, that's Hugh Kaufman's Herculean job. Kaufman, is a senior policy analyst for emergency response at the Environmental Protection Agency. He was chief investigator at of the EPA's clean-up of the World Trade Center, and a long-time critic of the agency's policies and practices. Living on Earth's Washington correspondent Jeff Young spoke with Hugh Kaufman at EPA headquarters.

YOUNG: Let’s see, there’s obviously a lot we don’t know about the situation in New Orleans because it’s just a mess and no one can do any real work there yet. But based on what you know about the area before this storm came through, what do you think is likely in that flood water in the way of contaminates?

KAUFMAN: Well, first of all you have a large amount of hazardous materials in the area. Industrial discharges to the sewers have now been released. Sewage that would go into the sewers and into wastewater treatment plants, all of that is being released. You have oil and gas from gasoline stations, and waste oils that have been released. You’ve got household hazardous materials; you’ve got pesticides; you’ve got chemicals. There’s a lot of hazardous materials storage areas in the area. So what you have is a witch’s brew of water that not only contains bacteria and viruses from sewage, but you also have heavy metals and other toxic hazardous materials.

YOUNG: How is this exacerbated by the environmental regulation and enforcement in that area in years past?

KAUFMAN: Well, what’s happened over the years because of the power of the major industry in Louisiana – which is oil, gas, and chemical – the environmental enforcement regulations to prevent releases if a catastrophe occurred are very weak in its enforcement. And so, you don’t have the kind of precautions that you would need for such an environmentally-sensitive area being brought to bear.

|

|

It’s also true for development. Because of the sensitive nature of the area – wetlands, etc. – and the fact that the area is susceptible to major hurricanes, you ordinarily would not want development to be as large as it has been allowed to in the last thirty or forty years. And so you had a tremendous population growth in areas that are very environmentally fragile, that are weakened in environmental regulation enforcement in terms of hazardous material control, and it was a crisis waiting to happen. And frankly, folks down there were living on borrowed time and, unfortunately, time ran out with Katrina. And now all the environmental hazards, or the worst-case scenarios, occurred, and now we’re seeing the results of bad planning which made for this catastrophe. YOUNG: It almost sounds like, sure, we have a natural disaster but the natural disaster kind of triggered a man-made one. KAUFMAN: Well, that’s correct. I mean, because the industries and the corporations could save, you know, millions of dollars a year by not having to meet good regulatory programs, now the taxpayers of the United States are going to be on the hook for, I think, over $100 billion to deal with this. Not even mentioning the untold horror to these poor people who didn’t have the money to evacuate. And now they are trying to get food, water, and they’re walking in toxic soup. YOUNG: What would it to properly dispose of the contaminates we’re talking about? KAUFMAN: Well the only way, because of the volume of the situation, the only way you’re going to deal with that water available without bankrupting the federal budget, is to send all that material into the Gulf of Mexico. You don’t have a choice. Now, once the water is gone you can do remediation of contaminates on the land and treat that material. It’s an expensive process, it’ll cost billions and take years to do properly. But you can certainly do that. You also have to repair and rebuild the sewage treatment plant and sewer infrastructure, as well as the drinking water infrastructure. I mean, you’re talking about a massive public works program of rebuilding that I don’t think we’ve seen in this country before, certainly not in my lifetime. YOUNG: Any guess what becomes of the Gulf of Mexico and its fishery, which is among the most valuable in the country? KAUFMAN: Well, I think there are going to be environmental impacts of that, and that’s why you’re going to have to monitor the release of this material. There might be some way to engineer, and you’re going to have to talk to the Corps of Engineers folks, some sort of program where you could do a controlled release so it all doesn’t hit the Gulf at one time. That’s one way to minimize the impact. But there’s no free lunch. There’s no way to deal with a catastrophe environmentally of this magnitude and not have environmental impacts. You’re gonna have them. What you want to do is minimize them, and that costs money. I mean, we’re talking about big money. We’re talking about like how much money we’re putting into Iraq. YOUNG: You know, the president compared what’s happening to New Orleans to 9/11, in terms of scale of destruction and the common will it’s going to take to get people back on their feet, etcetera. Is there another parallel there in that, you know, in the aftermath of 9/11 there was some contamination, the hazards of which were apparently downplayed. Do we face the kind of scenario here that we had there if officials are not straight with people in Louisiana about the extent of contamination from this? KAUFMAN: Well, I hope not. I did the investigation. At the time of 9/11 I was the chief investigator for EPA’s ombudsman. And so I investigated that case at the request of Congress, and found that EPA lied to the public at the direction of the White House about those contaminants. And they botched the remediation, and that’s why you have over 75 percent of the response workers very sick now and they’re starting to die off. This situation is a little bit more acute. In other words, the health effects for the common person who lives a mile away are much slower as a result of 9/11 than here. You’ve got, you know, hundreds of miles of people being exposed to hazardous material on a daily basis and so it’s right in your face. Hopefully, this administration will have learned from their mistakes and will not botch this remediation like they did the 9/11 remediation in New York. I’m optimistic. GELLERMAN: EPA officials say, quote, "Hugh Kaufman is welcome to speak as a citizen. But he does not speak for the agency.” And they tell us it's too early to tell the full extent of the environmental contamination. While the EPA's Hugh Kaufman calls Hurricane Katrina the worst-case scenario, Chris Roberie of Louisiana's Department of Environmental Quality believes it could have been worse….much worse. Roberie says department researchers flew over the New Orleans disaster area to determine the extent of oil and chemical spills. ROBERIE: Well, we haven't seen any chemical tanks or oil tanks or anything like that that ruptured from the air. It doesn't look like a major disaster in terms of tanks being ruptured. We are worried about railcars with chemicals in them. Refineries are out of service. Some of those refineries are flooded. We know there's some chemical contamination associated with that. And we're gonna have to get in there closer to do a better assessment at some point. GELLERMAN: What is your greatest concern right now? ROBERIE: Well, our greatest concern, one of the greatest concerns now is loss of human life and search and rescue. That's at the top of the list. What comes after that in terms of environmental assessment, there's going to be a huge waste debris issue that will have to be dealt with. If you think about homes being flooded to their rooftops, you've got damage d walls, you've got damage to goods like appliances and tv sets…all of that is going to be removed and disposed of somewhere. You're going to have to start up these various chemical companies back up. There's going to be flaring, there's going to be some pollution issues. We have a number of landfills down there and a number of those have been inundated with water. What are the impacts of that? The sanitary sewage infrastructure is critical. That has to be put back into service at some point before people can come back in in any great numbers. So, we're gonna have to do a number of assessments to try and answer those kind of questions. GELLERMAN: Just how long it will take New Orleans to recover from Hurricane Katrina is anyone's guess but history can provide a lesson about what not to do. In 1965, Hurricane Betsy struck the city. Mark Schleifstein is an environment reporter for the New Orleans Times-Picayune.

|