Here Comes the Sound

Air Date: Week of February 26, 2010

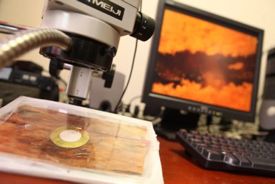

Blasting beetle sounds into tree pieces. (Photo: Richard Hofstetter, Northern Arizona University)

Bark beetles have eaten their way through millions of acres of forest in the West. Host Jeff Young talks to audio engineer David Dunn and researchers Richard Hofstetter and Reagan McGuire about using sound to combat the infestation.

Transcript

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young. Across the American West, millions of acres of forests are dead because of beetles about the size of a grain of rice – the pine bark beetles. The beetles’ range is expanding due, in part, to climate change. Warmer winters mean the beetles survive farther north and higher up. And drought weakens a tree’s resistance.

Forestry experts call it the largest insect infestation in North American history and warn some 20 million acres could be lost in the next decade or so. Now an unusual trio of researchers – a sound artist, a scientist, and a student – might have a powerful new way to control the beetles. And they found it by listening. We’ll hear from all three them and their remarkable little subjects, starting with David Dunn. Mr. Dunn’s an audio engineer and musician in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where the bark beetle has devastated some forests.

Audio engineer David Dunn in the recording studio. (Photo: Richard Hofstetter, Northern Arizona University)

YOUNG: That sounds like some pretty tight working quarters. How do you get recording equipment inside there?

DUNN: Well, you have to get some kind of microphone into that layer of the tree and that was the first challenge, and I spent oh, two, three weeks thinking about the problem and came up with a very simple solution, which is just to take what we call peazobenders (sp?), little, flat discs that are the output transducers inside of green cards and marry that to some kind of meat thermometer.

And these two things were glued together with a couple other little pieces of apparatus. When the beetles invade they leave little entry holes where they’ve bored into the tree a kind of sawdust comes out, and you can just push this device right through the outer bark into that layer.

YOUNG: So what did you hear when you first knew you had success?

DUNN: The first sounds I heard was just sort of a stirring, crackling noise that turned out to be the beetles moving.

[SOUNDS OF CRACKLING WOOD]

DUNN: After listening for a few minutes, suddenly I began to hear these little chirping and clicking noises, which are the distinctive sounds that they make.

[SOUNDS OF INSECT’S HOLLOW CHIRPS AND CLICKS]

DUNN: It’s very much like if you’d rub your fingernail across the surface of a phonograph or an LP and it’s a similar kind of sound.

YOUNG: David Dunn thought these recordings might be of use to entomologists. So he put out a CD of the beetle sounds in hopes that scientists would find it. And they did. Professor Richard Hofstetter and his research assistant Reagan McGuire study bark beetles at Northern Arizona University. And they’ve been working with Dunn ever since coming across that CD. Hofstetter and McGuire were already exploring ways to use sound to deter beetles, with mixed results – which is a pretty interesting story in itself. And they’re here now to tell us about that. Gentlemen, hello!

HOFSTETTER: Hello, this is Richard Hofstetter.

MCGUIRE: Hello, this is Reagan McGuire.

YOUNG: Where did this idea first come from to use sound to fight beetles?

MCGUIRE: Well, before I met Richard about five years ago I had read an article in the local paper that bark beetles had killed 74 million trees in Arizona and New Mexico in the last five year, and it got me to thinking about this is a problem that needs to be dealt with. All the sudden, I had the idea: why not use military control technology where they use acoustics to control crowds or Somali pirates to push them off.

Research Assistant Reagan McGuire. (Photo: Richard Hofstetter, Northern Arizona University)

MCGUIRE: Ha, I thought about what are the two sounds or the type of music that really annoyed me, and for me it was Rush Limbaugh and heavy metal. It turned out I had to play Rush Limbaugh backwards because I had to sit in the lab and monitor this all day long and he just drove me nuts – he was irritating.

[ALL LAUGH]

HOFSTETTER: Yeah, we quickly realized that any sound wouldn’t work, and after five or ten minutes, beetles made it sort of like a background noise where they eventually would ignore it.

YOUNG: Did you think of using The Beatles?

MCGUIRE: [Laughs] No, I happen to like The Beatles.

YOUNG: So playing music, talk show hosts, this didn’t work. You needed a different approach, what did you try then?

HOFSTETTER: You know, after we tried just any sort of noise, we thought we should be doing something that’s relevant to the insect. And the easiest approach right there was just let’s play back calls from insects to see if we can get a response. And we got a pretty strong response. For instance, we could play the call that the male would make when he meets a female, and we call it an attractant chirp or call, and he kind of sounds like a chu-chu-chu chu-chu-chu:

[MALE BEETLE’S ATTRACTANT CHIRP]

HOFSTETTER: And we’d make that recording, play it back and we’d see the female respond to this call:

[FEMALE BEETLE’S HOLLOW CHIRP RESPONSE]

HOFSTETTER: And so once we realized we could change behaviors we thought we were on to something pretty big.

YOUNG: So, what do beetles do when they hear these sounds?

HOFSTETTER: Uh, it depends, and it depends on the call being made and what behavior you’re trying to influence. For instance, they may start to tone in circles because of the input of the sound, they may block off the tunnel entry because of the sounds we put in.

Professor Rich Hofstetter with phloem, a tree layer inside the bark, and beetles. (Photo: Richard Hofstetter, Northern Arizona University)

MCGUIRE: And maybe one of the most striking things is why I’ve been able to watch a male mate with a female two or three times and then all of the sudden turn on that female and kill her – it will chew her to pieces. You know, you don’t see that in nature, that’s not natural. We’ve had a bark beetle actually chew through the Plexiglas to escape. Just remarkable behaviors, they kind of amaze us as we watch.

YOUNG: You’ve kind of become the voice on the workplace PA system telling them all what to do.

HOFSTETTER: In a way, that’s kind of what’s happening and that’s sort of our approach is that if we can change what they do we can stop them from killing a tree.

YOUNG: This is just astounding that you’re able to dictate their behavior so specifically in some cases here. I mean, it sounds to me like you’re really learning a lot more about pretty basic beetle biology and behavior here.

HOFSTETTER: Yeah, it’s definitely true and we have a strong interest in using this to reduce tree morality, but also we’re interested in the basic science here. We’re also very interested in how insects hear. We don’t actually know what frequencies they’re able to hear, we don’t know what body part is listening. For instance, is it on the feet, the abdomen, the antennae, we actually don’t know. We have several other colleagues that are pursuing these questions, as well.

YOUNG: I had no idea there were such gaps in basic understanding of how beetles even hear – we don’t know where their ears are?

MCGUIRE: No, and you have to understand that there’s a forty percent of the insects on the planet are beetles and there is no history, no understanding of their communications, at all.

The pine beetle. (Photo: Richard Hofstetter, Northern Arizona University)

YOUNG: Minor correction there, I would call it ear opening, but that’s just my bias in radio.

[HOFSTETTER LAUGHS]

YOUNG: Well, the laboratory part of this so far sounds just fascinating, but I’m still really puzzled, how do you actually do this out there in the field?

HOFSTETTER: I think out approach right now is inputting the sounds for individual trees and so we use a type of speaker device that has our recordings that we play into a single tree and this would couple or screw into a tree…

MCGUIRE: But also, we’re looking at being able to broadcast at some point and protect whole stands of trees and that is on the drawing board.

YOUNG: Beetle radio, you’re talking about?

[ALL LAUGH]

MCGUIRE: Yes, actually.

YOUNG: What do you think about how practical this might end up being – it sounds to me like it’s going to be a tad expensive to try to do this on a large scale?

HOFSTETTER: On a large scale, I think it may not be practical, but you know for high value trees on private property, campgrounds, roadsides, you know I think about the cost to spray a tree is in the hundreds of dollars if you’re going to use pesticides. And so this device actually would be quite a bit cheaper than that. And you think if you’ve got to spray every time it rains or every year, here’s a device that would be – I can’t say the cost, but maybe 50 dollars, roughly. But you’d only need that once and it would last for as long as you needed.

YOUNG: What’s your inclination here – will this work?

HOFSTETTER: [Laughs] Well, it works in the lab and it’s worked on logs and it’s worked in sections of trees. So we have a pretty strong idea that this will work.

YOUNG: But you’re fighting against some pretty powerful biology. I mean, will the beetles figure this out?

HOFSTETTER: I don’t think so, it’s possible that there are some beetles that wouldn’t be affected by the sound, and they may get into a tree and reproduce, but if we can reduce the fitness or fecundity of beetles by even a fraction, it will be helpful.

YOUNG: It sounds to me like you don’t have a deep animosity toward the beetle despite what it’s doing to your beloved woodlands.

HOFSTETTER: I don’t, you know, it’s given me a career! [Laughs] I can’t complain too much.

YOUNG: [Laughs] That beetle’s putting food on the table!

HOFSTETTER: They’re beautiful organisms. No, they’re actually not that pretty. They’re just black or brown and kind of look like a beetle, but they’re very complex in a sense of they sort of are keystone species, and so in that sense they’re very interesting to study because they actually create environments for many other organisms.

YOUNG: Richard Hofstetter and Reagan McGuire of Northern Arizona University. They say patents are pending on some of those sound recordings. And beetle audio device is being field-tested. Now, it’s tempting at this point to say something like – “new weapon in battle against beetles”. But, as Professor Hofstetter says, the beetles aren’t the enemy; they aren’t even really a problem under normal conditions. Conditions, however, are not normal – that’s the problem.

A warming world is a weird world where beetles spread due to climate change and maybe even contribute to climate change. If the beetle-killed trees burn, it pumps more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in a feedback loop with scary consequences. David Dunn gave all this a lot of thought while he was listening in on those insects ravaging the woods around his home.

DUNN: They are extraordinary little rich societies of creatures that have a purpose within the ecology of the forest, unfortunately things are changing so quickly in forests conditions that the behavior has gotten out of bounds and how this becomes its own condition that contributes to the change of climate. The problem is how we effect and how we participate within these natural cycles, and to what extent are we responsible for this or are we in the same position as the bark beetles? We’re going about doing our thing and this is largely an unconscious process.YOUNG: You really are listening to these beetles? I mean, not just sounds they’re making, you’re listening?

DUNN: It becomes a very important role to just simple do that, to listen carefully and purposefully to the conditions of the earth at this point, historically, it really is this is a very extraordinary historical moment that we’re living through. And we’re just obviously beginning to see this sort of passing through the eye of the environmental needle in a way that paying attention to these sensory conditions of our world is really a valuable task.

YOUNG: Audio engineer David Dunn talking with us about recording bark beetles. Thanks very much.

DUNN: You’re very welcome, glad to talk with you.

[BEETLES SQUEAKING, CRACKLING, CHIRPING]

YOUNG: Hear more of the beetles and learn more about the work by David

Dunn, Rich Hofstetter and Reagan McGuire at our website l-o-e dot org.

[MUSIC: Brad Mehldau “Mother Nature’s Son” from Largo (Warner Bros. 2002)]

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth