Part II: It's More Than a Tree Planting Movement

Air Date: Week of July 1, 2005

As tree planters in Kenya's central highlands have reforested their region, they've seen a change in fuel availability, the food they can cook and the vegetables they can grow. And the organization they've built to plant trees gives them a way to address other problems, including government. Green Belt has been at the center of conflict to create a more democratic Kenya. But many village members, especially women, say the most important change is in their sense of self worth.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

SINGERS: Wego-yo! Wasi no kyo!

[SINGING]

CURWOOD: We're hearing this hour about the Green Belt Movement founded by the Kenyan biologist, environmentalist, and Nobel Peace Prize winner, Wangari Maathai. Our story resumes in the Central Highlands of Kenya, in the district of Murang'a, where women tree planters wrote this song in Maathai’s honor.

[SINGING AND CHANTING]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet continues our story:

LOBET: Today In Murang'a, the landscape is lush and green. But the older women say back in the 1970s, it looked quite different.

[WAMBUI SPEAKING SWAHILI]

VOICEOVER: I can give you an example from here, right where we’re sitting.

LOBET: Green Belt veteran Margaret Wambui

[WAMBUI SPEAKING SWAHILI]

VOICEOVER: This was bare soil, all the way over to there, bare soil! The birds would take dust baths here. There weren't any trees or even grass like you see now. The soil you see over on that hill could even have come from here, because the wind was always blowing away our soil. We even called it "the devil wind".

[WAMBUI SPEAKING SWAHILI]

VOICEOVER: From the moment we planted these trees we've noticed our soil doesn't blow away anymore. Plants like these that you see just multiply now because the soil is rooted here, it stays put. And with these trees we now have fodder for our cows and firewood. That is the goodness of Green Belt. We're always singing the praises of Green Belt.

[WAMBUI SPEAKING SWAHILI]

VOICEOVER: When I was a girl there was a lot of firewood. But later we had to go farther, to the forest to get wood, far away. We even had to go by bus, it was so far, and come back by bus, too. And since we couldn't bring back very much in the bus, we would have to go again the very next day.

[WAMBUI SPEAKING SWALIHI]

LOBET: On the other side of the hill in Murang'a, another veteran leader, Edith Nyoki, sits in the shade of a stand of trees, on her property. She calls it her Garden of Eden.

[NYOKI SPEAKING SWAHILI]

VOICEOVER: We get wood planks for building, we get them from this very farm right here. And if you talk about eating, we plant fruit, fruit trees, we can even plant bananas, right here! This close to the house!

[NYOKI SPEAKING SWAHILI]

VOICEOVER: Yes, it is much better than it used to be.

[NYOKI SPEAKING SWAHILI]

“There was nothing in between these houses, you could see straight from one to the next. Now you can hardly see the next house!’ said Edith Nyoki. The bare spaces have been filled in with lush green vegetation. (Photo: Ingrid Lobet)

VOICEOVER: You could see very far! It was very dry. There was nothing in between these houses, you could see straight from one to the next. Now you can hardly see the next house!

LOBET: Are the trees what she feels most proud of, the biggest accomplishment of the movement in this area?

[NYOKI SPEAKING SWAHILI]

VOICEOVER: We came together as one, we became a group, as a group we rear our goats, we rear our cows, like these goats right here and we're very happy because we’re even getting milk from them. It's almost as good as the trees, this coming together.

[NYOKI SPEAKING SWAHILI]

LOBET: The women of Murang'a have another song they sing. "Switch on the light, Wangari. Now we can see, you have been our guide. We're grateful we don't rely on anyone anymore.”

[SONG: HUTIA SUI-SEE]

LOBET: As the Movement spread in the 1980s, like any good organizers, Green Belt workers adapted and refined their goals and methods. They had to when they came face to face with some painful realities, realities that reached inside Kenya’s society and soul. Wangari Maathai:

MAATHAI: I realized part of the problems that we have in the rural areas or in the country generally is that a lot of our people are not free to think, they are not free to create, and, therefore, they become very unproductive. They may have knowledge. They may have gone to school but they are trained to be directed. They are trained to be told what to do. And that is some of the unmasking that the Green Belt Movement tries to do, is to empower people, to encourage them, to tell them it's okay to dream, it's okay to think, it's okay to change your minds, it’s okay to think on your own, it's okay to decide this is what you want to do. You don't have to wait for someone else to tell you.

LOBET: But if a certain passivity is entrenched, how to move beyond it? Many Kenyans can't read, and for others, hunger is a day away. So civic education is now at the heart of Green Belt Movement work. It sounds like this:

[MURITHI LEADING A CALL AND RESPONSE IN A CHURCH ROOM IN MIRICI]

LOBET: When Green Belt organizers like Muriithi Kaburi visit a community, the energy between trainer and audience in a common native language--in this case Kikuyu--can be palpable, even if, as on this day, a wicked heat radiates down on the assembled through a metal church roof.

[MURITHI LEADING A CALL AND RESPONSE IN A CHURCH IN KALUCHO].

KAHARE: It's like you give people analytical skills to analyze their problems, not to just sing "problems, problems," like a song. You are telling them "Analyze your problems, and you can do something about them, don't just sit!"

LOBET: That's Njogu Kahare, another Green Belt staff member. Once a local Green Belt chapter has begun planting trees, organizers urge members to examine their community problems one by one.

KAHARE: All their problems they have in the world. So they list them. Sometimes they go to about 400, 500 and then you tell them “okay, are these the problems we have?” Yes. Let's see where they come from. And that is usually a very sensitive time when people are careful they are not incriminating themselves as the cause of the problem.

LOBET: Often, one problem the community identifies is corrupt local government.

KAHARE: So they see like "Oohhh...so a government can be bad without us knowing.” And also they start seeing themselves as a cause of many of the problems.

LOBET: For example, water may become scarce because someone illegally diverts the flow, so community members challenge each other.

KAHARE: Why do you do that? Why are you selfish? Now that is a root cause. You are selfish, you don't consider your neighbors, or the water is not being distributed properly. Or the chief favors you or the people in charge of that water favors you. And, therefore, the solutions could be, "now we need to make regulations that do not favor some people." Then they decide, “now we want to go into fair solutions."

LOBET: The community looks to solutions to food, water, and wood shortages that are within its power to address. It may decide to conserve water together, or to remove water-hogging trees from a nearby stream. It may insist on greater accountability from local officials. For the first 12 years of its existence, the Green Belt Movement worked this way, focusing on local concerns in largely rural areas. But in the late 1980s, that began to change when Wangari Maathai started connecting more dots, this time between Kenya's degrading land and its political leaders. As the movement broadened, it became more threatening.

MAATHAI: In the beginning I was intrigued because it’s such a benign activity. It's development, exactly what every leader speaks about and so I thought that we would be celebrated and we would be supported by the system. But what I did not realize then is that in many situations, leaders, especially leaders in undemocratic countries, have not been keen to inform their people to empower their people to help them solve their problems. They almost want them to remain needy, to remain poor, to remain dis-empowered so that they can look up to them, almost like gods and adore them and worship them and hope that they will solve their problems. Now, I couldn't stand that.

LOBET: A crucial moment in the evolution of the Green Belt Movement came in 1989 when the Kenyan government brokered a deal with media mogul Robert Maxwell to build a 60-story building and a four story statue of President Daniel Arap Moi in Nairobi's Uhuru Park.

MAATHAI: Here is a public park, the only huge public park, it is a beehive over the weekends, especially because that is where most people from low income areas escape with their families. And the ruling party at a time when it felt very, very powerful, like nobody could touch it, it decided to build this tower and take over the park.

LOBET: Maathai said she couldn't condone the project and call herself an environmentalist.

MAATHAI: Every city needs green spaces. Every city needs trees. Every city needs a space where people can rest without being asked questions and without being perceived as if they are intruding. Because they, too, need space. Space is a human right, you need space. And so I campaigned to have that space protected.

LOBET: Wangari Maathia's outspokenness drew immediate fire.

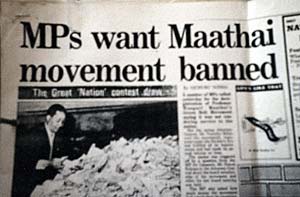

|

MAN: The Daily Nation, Nairobi, Thursday, November 9th, 1989. Members of parliament yesterday condemned Professor Wangari Maathai for appealing to the British High Commissioner over the construction of a 60-storey building at Nairobi's Uhuru Park. WOMAN: The Daily Nation, December 13 1989. President Daniel Arap Moi today attacked Professor Wangari Maathai for her objection to the media building at Uhuru Park saying even Jesus Christ would not have stood for this kind of interference. He said that "Wa mama" African custom calls for mothers to respect men. He wondered why other Kenyan women were sitting on the fence to endlessly witness her crusade. MAN: The Daily Nation. A number of Ministers of Parliament called yesterday for the de-registration of Professor Wangari Maathai's Green Belt Movement, saying it was not rendering service to the nation. An assistant minister, Mr. John Keene, said his great respect for women had been greatly eroded by her utterances. Mr Keene asked her and her clique of women to tread cautiously, adding "I don't see the sense at all in a bunch of divorcees coming out to criticize such a complex.” MAATHAI: That's when they reminded me who I am in terms of gender and what I am in terms of social status. And I was described in several adjectives which were very unflattering. Fortunately for me, and unfortunately for them, that did not deter me and I did not get intimidated. LOBET: A few years earlier her husband had divorced her, saying publicly she was too stubborn and too hard to control. She had transgressed when she became more educated than he was. She transgressed when she did not retreat after divorce and now she was criticizing the president. Another blow came at the end of that year. MAN: December 22, 1989 The Weekly Review. Last week, the Green Belt Movement war ordered by the commanding officers of the Central Police Station to leave within 24 hours the headquarters it has occupied for ten years. Despite Maathai’s pleas that she be give more time to organize her departure from the premises the officers stuck to their guns. LOBET: Maathia was forced out of her office and had to move Green Belt operations to her home. But staying at her house was now dangerous. Professor Vertistine Mbaya is a longtime friends and fellow scientist. MBAYA: The thing to remember is the amount of money that must have changed hands and would change hands. So when they became angry, we knew they were very angry. LOBET: In what would mark a historic shift for Kenya, the financing for the Uhuru Park media tower fell apart. The project died. Friends moved Maathai from house to house. She was jailed in 1991 for protesting deforestation , but was released. And when a group of mothers of young men who were being held as political prisoners approached her and asked her to help them free their sons, she said yes. MBAYA: And then she came up with a strategy that we would build a camp on Uhuru Park and have a candlelight all-night vigil. MAATHAI: And we went to this park, which is the Freedom Park, Uhuru Park in Nairobi and went to a corner opposite that building and we camped there to wait for the sons. And it was while we were there that a lot of people came to that site. [SINGING] MAATHAI: They came to the Freedom Corner and it was almost like a forum where people narrated their torture, what they had gone through, in the torture chambers of a building that was opposite the park called Ngaio House. It was like a truth commission at the park. MAATHAI: And men were crying tears because of the experience they had gone through. And that was the very first time people had found space to talk about their persecution, to talk about the oppression of that government. [SINGING] MAATHAI: For three days we were surrounded by security personnel. And every day they brought more security and surrounded the women. And on the third day they came with guns and a lot of soldiers and they completely uprooted the entire camp. [SCREAMING CROWDS OF PEOPLE] LOBET: In an act that was widely reported and perhaps misinterpreted, some women disrobed after police forced a dispersal. Maathai, who was clubbed unconscious, described that event to the radio program Democracy Now. MAATHAI: When the government unleashed its terror on us and the people who were with us there, several hundreds of them on that day…the women in the traditional African demonstration of anger and frustration by women. When women are confronted, punished, threatened by men who are old enough to be their sons that is extremely humiliating. Because whatever you do as a man you must not touch your mother, you cannot beat your mother, you cannot hurt your mother, and so what these women were doing to these soldiers is to tell them, “I curse you as my son. for the way you are treating me and I’m your mother!” LOBET: The protesters sought protection at All Saints Cathedral in Nairobi. The bishop there allowed the women to stay in the church basement for months, until nearly all their sons were freed. What began as a three-day hunger strike became a one-year struggle to open up Kenya's political system. [WOMEN CHANTING AND SINGING] CURWOOD: You're listening to a special production of Living On Earth--the Green Belt Movement's effort to restore the lands and lives of Kenyans, lead by the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize winner, Wangari Maathai. As you've heard, in its first twenty years, Kenyans planted millions of fast-growing trees ...allowing people to cut them, too, for fuel or for building, trying to plant more than they cut. In just a moment we’ll learn how Wangari Maathai’s Green Belt movement grew from an effort to reforest Kenya into new strategies to address nutrition, river restoration, and poverty. Stay tuned to Living on Earth. [CHANTING AND SINGING] ANNOUNCER: Support for NPR comes from NPR stations, and the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, online at mott dot org, supporting efforts to promote a just, equitable, and sustainable society; the Kresge Foundation, building the capacity of nonprofit organizations through challenge grants since 1924. On the web at kresge.org; the Annenberg Fund for excellence in communications and education; and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, from vision to innovative impact, 75 years of philanthropy. This is NPR, National Public Radio. [MUSIC] Living on Earth wants to hear from you!Living on Earth Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth! NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

|