Oil Dispersants and the Ecology of the Gulf

Air Date: Week of December 7, 2012

Gulf oil spill on the beach (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

During the 2010 Gulf Coast oil spill disaster, BP used a chemical called Corexit to disperse the slicks. According to a paper recently published in the journal Environmental Pollution, that decision may have increased the damage to the marine environment. Terry Snell, Chair of the School of Biology at the Georgia Institute of Technology, discusses his findings with host Steve Curwood.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. In April 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon disaster ravaged the Gulf of Mexico, BP decided to use a chemical called Corexit to try to disperse the gushing oil. The use of dispersants was controversial at the time, and now scientists have released the results of laboratory experiments designed to assess what effects that dispersant - oil mix may have had on the Gulf of Mexico. The experiments used marine plankton called rotifers. Dr. Terry Snell, chair of the School of Biology at Georgia Tech was one of the researchers.

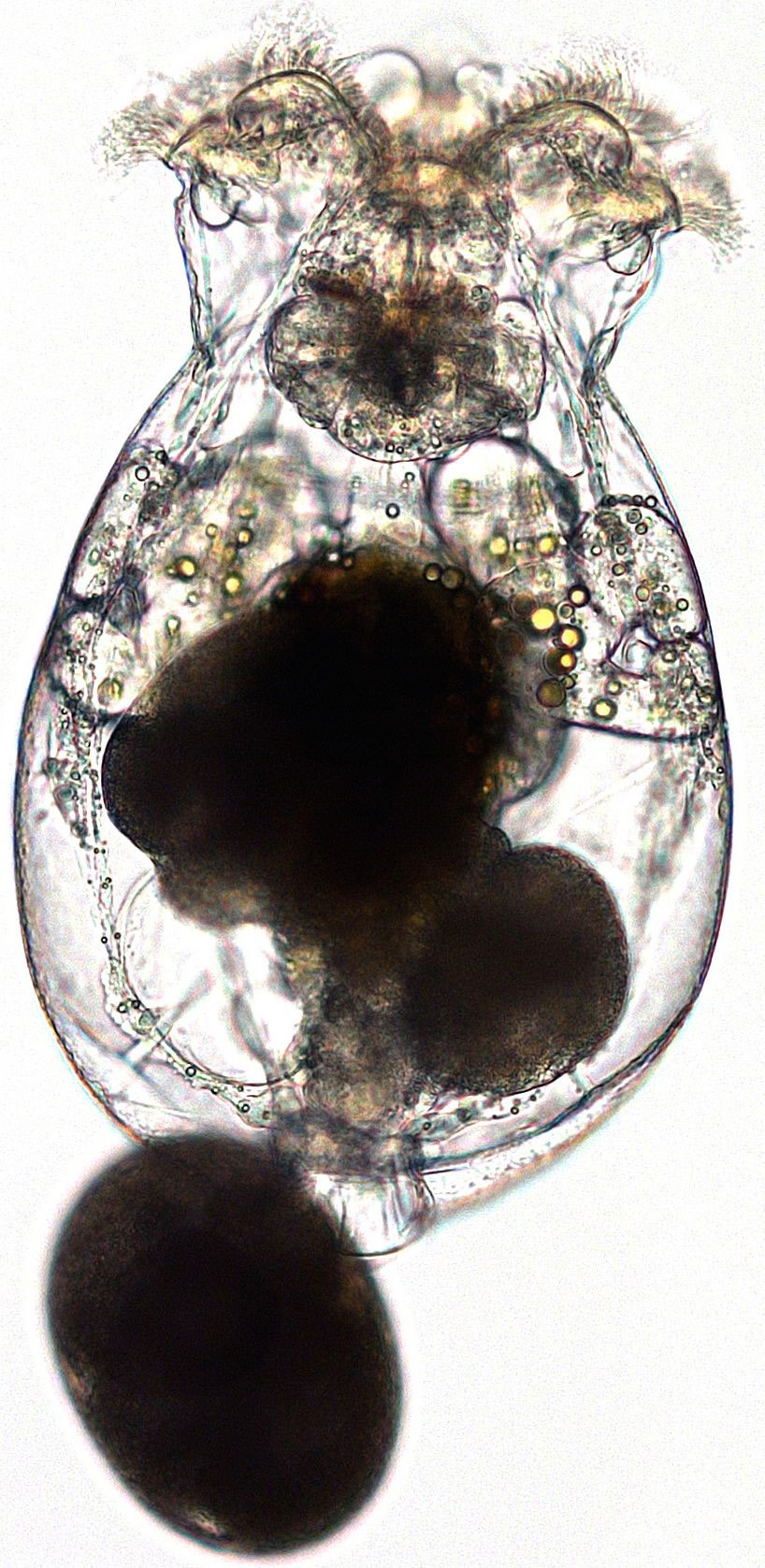

SNELL: Rotifers are animals, they're microscopic but they have all of the complex systems that any other animals have. They're useful in ecotoxicology because we can expose these animals to a variety of toxicants, and we can kill them by the millions without anybody caring very much.

A female rotifer (photo: Terry Snell)

CURWOOD: Well, now the study findings have been published in the journal Environmental Pollution, with Terry Snell as one of the lead authors.

SNELL: We were interested in what the consequences might be of using this dispersant Corexit in treating the oil spill from the Macondo oil well head. And we had a suspicion that there might be some synergistic effects in terms of the toxicity of the oil and the Corexit that may not have been observed or recorded previously. We tested whether when you mix the oil and the Corexit together, you get a larger toxicity than you would have with either the oil or the Corexit by itself.

CURWOOD: And, what were your results?

SNELL: In fact, we saw significant synergies between the oil and the Corexit. As much as 52 times greater toxicity when we applied the mixture in the test versus when we applied either the oil or the Corexit by itself. In toxicology, we are measuring something called a LP50, or the concentration it takes to kill 50 percent of the test organisms in the test period, in this case 24 hours. So, when we say it’s about 52 times more toxic, that means that the concentration that it takes to kill 50 percent of the organisms in 24 hours is 52 times lower than the original concentration.

CURWOOD: And the point here is that the rotifers are a marker for the entire ecosystem? That as a biologist you would be concerned about all of the organisms there in the ocean?

SNELL: Yeah, so the rotifers are what we would call a model organism. A biomarker representing the planktonic ecosystem. We tested this component of the planktonic ecosystem – that is rotifers – to get a guage for whether this component of the ecosystem was harmed. And, in fact, it was. Now, we leave it to other people to test fish and crabs and other components of the marine ecosystem, but rotifers are the base of the food chain. That is, they are filter feeders who eat the algae, and they are in turn making that energy available to higher tropic levels like larval fish. So, the larval fish themselves cannot eat the algae, they have to eat something that is capable of consuming the algae, the algae is the base of all the food chain.

CURWOOD: What were scientists saying about dispersants back in 2010 when the Deepwater Horizon oil spill occurred?

SNELL: I think the concern back then was that we didn’t know enough to use these kinds of chemicals on such a broad scale, and that the basic research that should have been done before the disaster was not done and the information simply wasn’t there.

CURWOOD: Now, why do you suppose that BP used this dispersant against the advice, against the concerns, of a number of biologists?

SNELL: I think that BP used the dispersant at the direction of the Environmental Protection Agency. I mean obviously they were very concerned about the oil rolling up onto the shores and into the marshes. What the dispersants do quite effectively is to make the oil disappear because it goes from big globs into very small, hard to see droplets. So, in the decision to keep the oil off the beaches, they kind of roll the dice biologically and hope that there wasn’t any major impacts in the marine ecosystems. And it turns out, at least in this planktonic ecosystem, there were substantial impacts.

CURWOOD: You don’t have the hard data, but in the end, what do you suspect the ecological effect of this massive use of dispersants was on the Gulf?

SNELL: The Gulf, of course, is a huge, massive, complex ecosystem, so it’s hard to say exactly what the effects will be. I mean, what we focused on was a small component of that system, and what we can tell you is that there were two main effects. One is a suppression of rotifer abundance and biomass in the water column. That suppression probably didn't last more than a few months. The second maybe more worrisome effects is that there is toxicity in the benthic community to the dormant eggs that these rotifers produce.

CURWOOD: Benthic is the bottom, of course.

SNELL: The bottom. So these eggs that are lying in the sediments on the bottom are the things that will recolonize the water column in the spring and allow the population to regrow. Not only do rotifers produce these dormant eggs, but also algae and also dinoflagellates, and copepods produce these. So, the whole planktic community is reconstituted every spring from those dormant eggs in the sediment.

If those dormant eggs in the sediment don’t hatch because of the toxic effects of the oil and the dispersant, then there is going to be less biomass available for the small animals that feed on these plankton, namely larval fish, larval crabs and larval shrimp. So, we expect to see those populations also suppressed, and this may happen over a span of several years.

CURWOOD: So, the Gulf of Mexico is a pretty tough place now for marine creatures to operate. We’ve had of course these dead zones that don’t have oxygen. We’ve had this massive oil spill, now dispersants have been added there. Overall, what concerns do you have about the health of the Gulf as an ecosystem?

SNELL: Well my concern is that these stressors are cumulative. And you can take any one of those stressors maybe by itself but it takes years to recover from a stressor of the magnitude that we saw from the oil spill. And then when you add each stressor onto the load of stressors that the organisms are Bering, and you put in things like climate change, global warming, ocean acidification… these things are presenting more and more challenges to the animals and plants that live in the Gulf.

And my worry is that at some point these challenges may be so great that we may come to a tipping point, when the populations might in fact crash as a result of these cumulative effects.

CURWOOD: Terry Snell is Chair of the School of Biology at the Georgia Institute of Technology, thank you so much!

SNELL: You’re welcome.

CURWOOD: We contacted Nalco, the makers of the dispersant Corexit; they declined to comment on the study.

Links

Study on dispersants and oil published in Environmental Pollution

More about Prof. Terry Snell, chair, School of Biology at Georgia Tech

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth