Alternative Tar Sands Pipelines

Air Date: Week of July 5, 2013

|

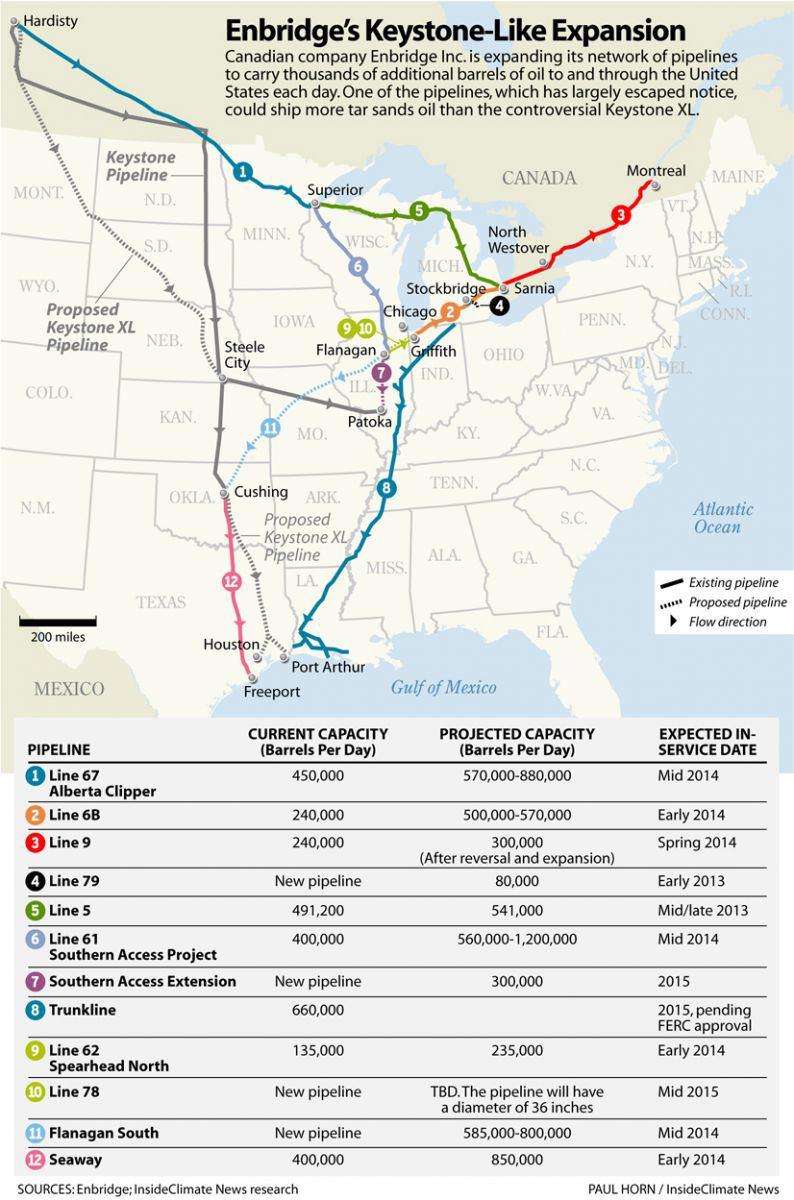

While all eyes are focused on the Keystone XL pipeline, oil company Enbridge is quietly planning to expand a web of other pipelines to bring Alberta Tar Sands oil to ports. Lisa Song from InsideClimateNews details the pipeline projects to host Steve Curwood.

Transcript

CURWOOD: In his recent address on climate change, President Obama pledged not to approve the Keystone XL pipeline if it would add significantly to global warming. Many Keystone opponents heard that as a death-knell for the project, but the overall climate impact of the pipeline will depend on whether the diluted bitumen, dilbit, from the Canadian Tar Sands would be able to get to the market anyway. And there may be another way. According to the online publication InsideClimateNews, the Enbridge Company has been quietly exploring the expansion of its existing network of pipelines in the US and Canada to get more dilbit to market. InsideClimate’s Lisa Song checked into this, and I went to her office to see the map of the proposed pipeline expansions.

SONG: These pipelines would primarily transport oil from Canada, and means a lot of the same kind of dilbit oil that would be in the Keystone XL. These pipelines would also transport American oil because they’re expansions on Enbridge’s existing network of pipelines in the US. Enbridge right now has an oil pipeline that goes from Canada to Wisconsin, and that carries a little less than 500,000 barrels a day of this dilbit oil. And the company is looking to expand that pipeline and almost double it in size up to 880,000 barrels a day. And if they manage to do that, the pipeline will be larger than the Keystone XL.

CURWOOD: Let’s go to the computer screen now and if you want to follow along at home, we’re at InsideClimateNews.org. And we see a map of Alberta, there’s this web of pipelines. Describe how it gets to Port Arthur and Freeport on the Texas coast.

SONG: Well, it’s hard to say exactly, because it’s a web of pipelines. Some of them go to Montreal; there’s a bunch in the midwest, and then some of those pipelines go down to Texas and the Louisiana gulf coast. The way the oil is moving generally is from north to south, from Canada to the gulf coast. But once you have the oil in a specific pipeline, it’s hard to say exactly where it will go next. But a lot of these pipelines are existing pipelines that Enbridge either wants to increase in size, or transform from one type of pipeline to another. So, for example, there is a pipeline called the trunk line, which goes from the midwest down to the gulf coast. Right now, that pipeline carries natural gas. But Enbridge has a plan to change it to carry crude oil down to the coast.

Map of Enbridge’s proposed pipelines (image: Paul Horn/InsideClimate News)

CURWOOD: Let’s see, looking on the map here, I notice this pipeline that goes over to Montreal. This must be the one that folks are talking about bringing oil out through Maine to the ocean?

SONG: Yes. There’s an existing pipeline that goes to Montreal and it stops there. And right now, Enbridge is reversing that line so they can start pumping oil from the west to the east, to Montreal. And there are environmentalists who are afraid Enbridge will want to expand that line and build it further east from Montreal to Maine, and eventually to the coast. But there aren’t any concrete plans to do that yet.

CURWOOD: Now, if I do the math here - if Enbridge builds this one and there’s a Keystone XL, then all kinds of tar sands oil could come through the US.

SONG: You know, right now in Canada, they’re producing a lot of tar sands oil, and there’s not enough pipelines to bring that oil out of Canada and into the US. So whether both pipelines get built, or just one of them, the industry will certainly want as many as they can get.

CURWOOD: So, what’s the regulatory situation here? Who has to approve this Enbridge plan?

SONG: It’s also the State Department. They have to basically give Enbridge a permit before the company can complete the expansion. The State Department needs to write an Environmental Impact Statement before they can make a decision. And they’re just getting started in that process. So I think they’re taking public comments right now.

CURWOOD: How much pushback has there been from campaigners who’ve been opposing the Keystone XL on the grounds that it would promote global warming?

SONG: There hasn’t been very much attention on the Enbridge pipeline, just because the Keystone has taken up most of the space, and most of the attention. But I think it’s something that people who are opposed to Keystone are aware of, and I’m sure it will get more attention over time. It’s already gotten more attention recently because they put forth a formal proposal to the State Department.

CURWOOD: Lisa Song, give us the quick science lesson about why there’s such concern over this diluted bitumen and the process of getting it out of Canada?

SONG: Well, the problem is, bitumen is thicker than conventional crude oil, the type of light and medium crude oil that we’ve traditionally shipped in the US, and that our pipelines were built to ship. So when this oil spills out into the environment, what happened, for example, three years ago in Michigan, there was a million gallon dilbit spill in a river. And once the dilbit spilled, the light chemicals eventually evaporated, and all you had left was the heavy bitumen, and it sank to the bottom of the river where it’s really hard to clean up. So that’s the worry that if we start shipping more of this dilbit, then what happens when it spills? We still don’t know how to clean it up.

CURWOOD: Now recently, the National Academy of Sciences had a report looking at pipelines carrying both crude and diluted bitumen, and said they’re about the same. But what kind of assessment do they give in case of a spill?

SONG: So the study only looked at whether diluted bitumen is more corrosive to pipelines than regular crude oil. The NAS scientists did not look at the consequences of a spill at all. And that’s because the study they did was ordered by the Department of Transportation, and it came out of a pipeline safety bill that was passed in 2012. So the DOT told the academy, we want you to say whether pipelines are more likely to leak when they have diluted bitumen in them rather than conventional oil, but they did not ask the committee to look at what would happen if diluted bitumen spilled out of the pipeline. And so that means part of the question about the risks of dilbit and how it compares to regular crude oil hasn’t been answered.

CURWOOD: Lisa Song is a reporter with InsideClimateNews. Thanks so much, Lisa.

SONG: Thank you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth