Life in Chernobyl and Fukushima

Air Date: Week of January 17, 2014

The red specks in this photo are actually traces of radiation hitting the camera lense. (Saha Kupny)

Chernobyl, Ukraine and Fukushima in Japan were the sites of the world's two worst nuclear disasters. Years later some residents choose to stay in the affected communities instead of moving. Michael Forster Rothbart tells host Steve Curwood about his new photo documentary showing the lives of ordinary citizens that remained behind.

Transcript

CURWOOD: When any disaster forces people from their homes, those who survive face the choice of eventually returning or starting anew someplace else. But when the disaster isn’t over in a couple days but lingers for generations, and when your home may not be safe, it's a tough choice. People who lived near nuclear power meltdowns in Chernobyl, Ukraine and Fukushima, Japan, have considered those alternatives, and it’s the central question of photojournalist Michael Forster Rothbart’s recent book, Would You Stay? Michael, welcome to Living on Earth.

ROTHBART: Thanks, Steve, it's good to be here.

CURWOOD: So you spent two years living near Chernobyl, and you’ve also spent a lot of time living near Fukushima, Japan, describe those two regions for us.

ROTHBART: It’s interesting. If you go into the exclusion zone in Chernobyl or Fukushima, they actually feel quite similar. There’s just a feeling of small farming towns that have been forgotten and then abandoned. But people have this vision of the Chernobyl exclusion zone being a dead zone, and really, nothing could be further from the truth. There’s a lot of plant life, there’s a lot of animal life, and there’s actually a lot of people still living and working in the Chernobyl exclusion zone.

CURWOOD: Of course, they’re not allowed in the Fukushima exclusion zone yet.

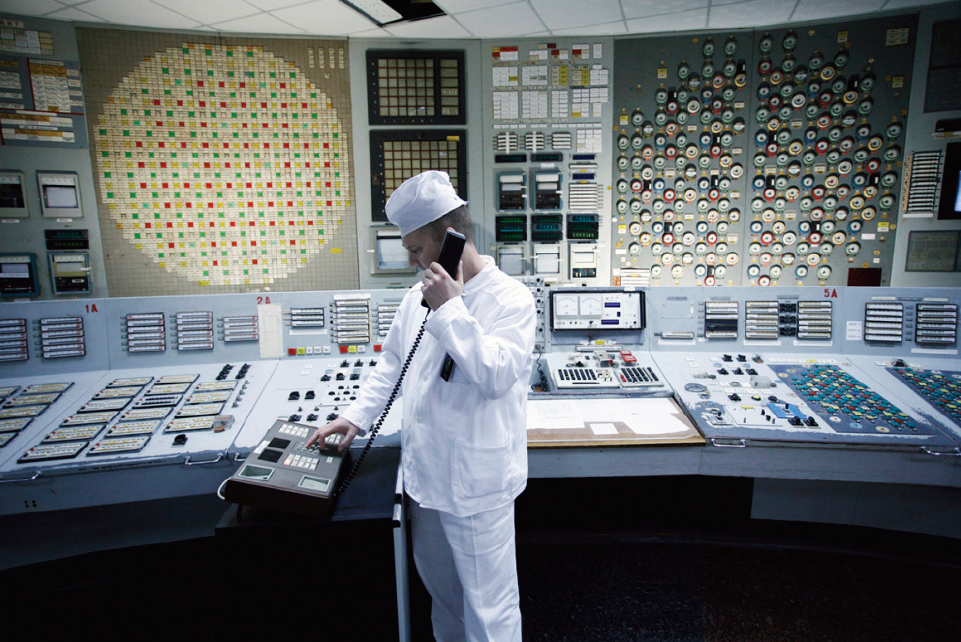

A shift supervisor keeps an eye on things inside the Chernobyl control room. (Michael Forester Rothbart)

ROTHBART: The Japanese government’s very eager to try to get people back into the Fukushima zone, and so they’ve actually designated three different sections of the zone, one section they’re hoping to get people back in as soon as possible, and obviously, the more contaminated zones, it could be decades or centuries before people are let back in.

CURWOOD: When you look in these areas very close to Chernobyl, it doesn’t look like a disaster zone, you say.

The forest around the Chernobyl nuclear reactor appear normal unless you know what you are looking for. (Michael Forester Rothbart)

ROTHBART: If you know what to look for, you can definitely see the signs of radiation, but if I’m just walking through the woods, it looks like a quiet forest anywhere. I spent a lot of time with these biologists who taught me how to see the signs of radiation. For example, pine trees typically have something called “apical dominance” which means that the branch that grows the most is the topmost branch, and just continues to grow up and up and up, and that’s why you get pine trees with narrow triangular shape. But because of the radiation that has stopped them, instead you get these distorted trees with branches going out in every direction, and they look more like shrubs than trees. So that’s just one simple example.

Nina Dubrovskaya (center), Michael Forester Rothbart’s landlord has tea with friends in her kitchen. (Michael Forester Rothbart)

Also, I saw with these biologists I saw birds that had minor deformities. And so there’s actually an interesting scientific debate that’s been going on for years in Chernobyl because one school of thought says that actually humans are the biggest disruptor to natural life, natural habitat. So if you take the humans out of the equation by creating these exclusion zones, actually the animals do quite well. The people in that camp cite there are wolves that have returned to the Chernobyl exclusion zone, there are actually wild horses that were reintroduced there that are doing reasonably well. But the other school of biologists have been doing some very careful studies - bird counts and things like that - discovered there are insects and birds and other animals you’d expect to find there that are not there, and that there’s some direct correlation between the level of radiation in a particular spot and what is living there.

CURWOOD: Of course, Fukushima’s a disaster is a lot younger. What were you able to see in the exclusion zones that was, well, different?

ROTHBART: Well, when I first went into the Fukushima exclusion zone, I was actually amazed how similar it looked to the Chernobyl exclusion zone. The same little farming villages, and a

feeling of abandonment. What’s different in Japan I found...well, first of all, is the scale. Estimates are that Fukushima released between 10 and 30 percent of the amount of radiation as Chernobyl, and Chernobyl actually contaminated an area of about 56,000 square miles, which is roughly the

size of New York state, whereas Fukushima, the area that was contaminated is closer to the size of Connecticut, about 4,500 square miles, you know, maybe 10 percent of the size.

Temporary housing for Fukushima residents displaced after the tsunami and meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear reactor. (Michael Forester Rothbart)

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about a couple of specific pictures here, Michael. Tell me about Sasha Kupny, he’s a Chernobyl plant worker.

ROTHBART: Sasha’s an interesting character. He’s an amateur photographer, and so although he’s been working at the Chernobyl plant for decades, his dream really was to take pictures, and so we became friends. Sasha Kupny showed me this photograph that he had taken inside the sarcophagus, basically, in the reactor hall, and what’s amazing is the picture, if you zoom in on it and look closely, is you see these green, blue and red dots on the picture, what it’s showing is basically radioactive particles hitting the camera sensor during the one-second exposure. But Sasha described the experience to me. I asked, “Why are you willing to go in here,” and he said to me, “Have you ever climbed a mountain? Well you know when you get to the top and you look around and you realize you’ve gone as far as a human can go?” He said that he had that feeling inside the reactor hall.

CURWOOD: Now there’s another photo. This one’s from Fukushima. I think it’s rather telling. There’s a man who’s straightening bicycles in a bike rack. Why is he doing that?

ROTHBART: One day, I came back from being in the Fukushima exclusion zone, and I got back to Fukushima City, and right outside the train station, there’s a man straightening bikes. And I watched him for a while, and I talked to him, discovered that this is his job, 12 hours a day, seven days a week. It’s basically to take bikes that people park and line them up. He measures them out with his feet so they’re all about 12 inches apart, and he just goes down the line and he makes them all parallel and neat. And I couldn’t help thinking, why, when there’s so many needs for so many people, would you be spending government money, municipal money, to pay someone to straighten bikes. I think the answer is that people have a really strong desire for normality. So even when there’s chaos around you, perhaps even more when there’s chaos is around you, you just want some things to be normal. In this country, we wouldn’t care...a chaotic bike rack, we wouldn’t even notice it. But in Japan, which is a culturally orderly society, people do notice that the bikes are in disarray, and that disturbs them, and so it’s worth it to them to pay somebody to continue to straighten them.

CURWOOD: So how does the culture in Japan compare to the culture of Ukraine in terms of how people have reacted to these nuclear disasters, at the time and following?

ROTHBART: To make some broad generalizations about culture, I’d say the Ukrainians stereotypically are this pessimistic culture, that things are terrible and they’re never going to get better, so let’s just share another bottle of vodka...

CURWOOD: ...and complain, huh?

A worker near Fukushima straightens bikes to make the city feel more orderly and comfortable for residents. (Michael Forester Rothbart)

ROTHBART: ...and complain, all the time, of course. And if you don’t have a good complaint, then you have to think one up. Whereas in Japan, I learned this word called gaman, which translates sort of loosely as stoicism, but it’s much deeper than that. It’s sort of taking pride and being able to survive any situation and very specifically to not complain, not to show people that you’re struggling, to continue living and doing the best you can, and going on, no matter what the circumstances are. It’s interesting now the state government, the prefecture government in Fukushima, is really pushing people to downplay the consequences of radiation, to say, life goes on, things are fine. Let’s promote our city, let’s promote our prefecture and encourage tourism to come back. Because there’s this social pressure not to complain, and not to talk about your fears, people are very close-mouthed, you have to get to know people pretty well before they really start to open up and talk about what they’re afraid of.

CURWOOD: Now that the government is saying, well, you can’t quite move back to the way we thought you could, how are people reacting? How do you think they’re going to react to that news?

ROTHBART: Once people lose faith in their government, it’s really hard to regain it. And I heard this over and over again in Japan, that people said, we trusted the government and they let us down. They lied to us, they misinformed us, they weren’t there to help us, so people lost faith and I think this latest news that people who they’re promising would be able to return may not be able to return is just another nail in the coffin. Like 9-11 in this country, the Fukushima disaster was a watershed moment for Japan where everything changes. And I think decades from now looking back, people say nothing was ever the same after Fukushima.

CURWOOD: So why do you suppose that some people stay, and others go? What’s the typical answer that people would give you when you asked them why they were staying in places like right near Chernobyl?

ROTHBART: I really found two things: one is that people replied to me and said, “well, why should we leave?” It’s hard for us to understand it. We live in such as transient world in this country. We’re so mobile moving every couple of years, but if you live in the same house as your ancestors, it takes a lot of uproot you. I talked to some old woman, for example, who said, “OK, we’ve been through the Nazis, we’ve been through a famine, we’ve been through changes in government, and all these terrible things that have happened to us in the past, we’re not going to leave just because of some invisible radiation. And I think the most basic reason is just because this is home, and home is such an important notion to people. People suffer great difficulties in order to stay in their home.

CURWOOD: Michael Forster Rothbart’s book is called Would You Stay? Thanks so much, Michael.

ROTHBART: It was great talking with you, Steve. Thanks for having me.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth