The (So Far) Elusive Dream of Carbon Capture And Storage

Air Date: Week of May 16, 2014

Tom Crooks, of the R.G. Johnson Co., at his company's new workshop in Waynesburg, Pa. The coal mining construction company has about 35 laid-off employees. Photo: Reid R. Frazier

Concerns about rising carbon dioxide levels mean that coal must capture and sequester its CO2 emissions to have a future. But Reid Frazier reports that despite years of experiments there is still not a cost-effective way to employ carbon capture technology at coal fired power plants.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Mining and burning coal goes back in the ages. China used coal as early as 3400 BC, and of course it fueled the Industrial Revolution beginning more than two centuries ago. Today it's a fuel under fire as a driver of pollution and global warming. And while coal still leads electricity generation in the US, the industry has been put on notice that it must adopt a low-carbon diet to survive. Carbon capture technology could be the answer, but as Reid Frazier of the public radio program the Allegheny Front reports from western Pennsylvania, even after two decades of research that technology is still not ready for prime time.

FRAZIER: Tom Crooks walks through a brand new industrial building in Waynesburg in the southwest corner of the state. This is Pennsylvania’s coal-mining country. Some of the biggest mines in the state are right down the road. There are stacks of supplies and machinery in tidy bundles scattered throughout the floor.

CROOKS: You see some drill steel, you see hoses, these are for spraying concrete.

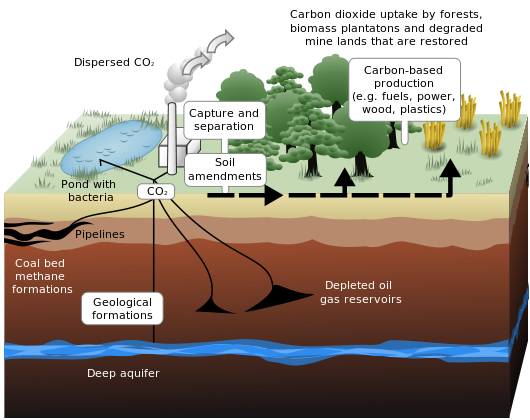

A diagram of carbon capture and storage. (Wikipedia Commons)

FRAZIER: Crooks is a vice president of the RG Johnson company, which helps build coal mines in Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

CROOKS: We spray concrete on the ceiling to help hold up the mine roof. A lot of what we do is concrete construction in the mines for the big infrastructure materials. A concrete floor like you see here that we’re standing on—in the coal mine we have concrete floors.

FRAZIER: The company just built this new workshop. Crooks says it’s a sign that the company thinks coal is here to stay. But there are signs the industry’s prospects are tenuous. RG Johnson has 150 employees, but not everyone is working right now.

CROOKS: So we have about 35 people laid off. That’s not what we want. We want to have 150 people working, full-time, all the time.

FRAZIER: Crooks says federal carbon regulations are partly to blame. A recent UN climate report found the world will need to drastically cut CO2 emissions to stave off runaway global warming. To cut emissions in the U.S. the EPA recently proposed requirements that NEW coal plants use carbon capture and sequestration. This is a technology that takes CO2 produced from coal combustion and pumps it underground. And the EPA is in the process of writing regulations for existing plants, that could also require carbon capture.

Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett at a coal conference April 22. Corbett says the EPA's carbon regulations will hurt the coal industry. Photo: Reid R. Frazier

This has the coal industry worried. Carbon capture is expensive, and still in its developmental stage. Last summer, FirstEnergy closed two coal-fired power plants in Pennsylvania, saying compliance with current and future environmental regulations would simply cost too much to keep them open. Crooks sees this as part of a trend.

FRAZIER: The reality of it is, this industry would be much more healthy if there weren’t the potential of the regulations.

FRAZIER: This has politicians from coal states—like Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett—on the offensive. At a recent coal industry conference, Corbett lashed out against the EPA’s carbon regulations.

CORBETT: We need to work with the industry, and not in opposition to the industry. Simply regulating coal out of existence doesn’t solve anything.

FRAZIER: Corbett told the industry executives in the crowd that he’s confident new technology can reduce coal’s carbon footprint. He invoked the space program, which has developed an international space station and landed a Mars Rover.

CORBETT: If we can do that, you can’t tell me that it’s not possible, given the time and given the right approach and given help from Washington, that we can’t come up with a solution, of cleaner air and getting rid of greenhouse emissions.

FRAZIER: Carbon capture has been around for a while, but there are only a handful of full-scale projects implementing the technology right now. The first carbon capture coal plant in the U.S. is under construction in Mississippi. But that plant is billions over-budget and behind schedule. Carbon capture is energy intensive, and requires multiple steps to get the carbon out of flue gas and into a compressed form that can be pumped underground.

Michael Matuszewski of the Department of Energy’s National Energy and Technology Lab near Pittsburgh, says part of the difficulty with developing the technology is CO2’s chemical makeup--it doesn’t make it very easy to work with.

MATUSZEWSKI: CO2 is a lazy molecule, it doesn’t really want to do a lot chemically, so it’s difficult to manipulate, in that sense.

FRAZIER: All of this would make coal fired-electricity about 40 percent more expensive to produce.

Howard Herzog, an engineer at MIT, says the problem with carbon capture isn’t technology. It’s policy. Without a price on carbon emissions—either through a cap and trade system or a carbon tax, carbon capture isn’t price competitive.

HERZOG: If you do something like put a market price on it—then I think coal has a fighting chance with this technology.

FRAZIER: But putting a price on carbon has been tough in the U.S. A plan in 2010 to pass a cap-and-trade system died in the Senate, and won’t be taken up again anytime soon. Without a price on carbon, the Obama administration has used EPA regulation to try to address climate change. Herzog said he thinks the coal industry could thrive under a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system.

HERZOG: I think coal will do better under a carbon price than it will under the path we’re going down now. Because the path we’re going down now is coal’s in everyone’s target. They’re basically trying to get coal out of the marketplace in any way they can.

FRAZIER: At a conference in Pittsburgh, a few hundred geologists and engineers gathered to compare notes on carbon capture projects all over the world. Philip Jagucki, of Schlumberger Carbon Services, says his company is already pumping compressed carbon dioxide into sandstone at a demonstration project in Illinois.

JAGUCKI: The goal of the project was to inject a million tons of CO2. Right now we’re at 800,000. The project is expected to finish in November, of 2014.

FRAZIER: He thinks the progress at his and other projects means that carbon sequestration isn’t too far off.

JAGUCKI: It’s definitely not far in the future because we’re doing it right now—I mean we know how to do it.

FRAZIER: Jagucki says there are technical aspects that still need to be improved —like pulling CO2 out of the smokestack. Solving these problems is a critical step to help combat climate change, says John Thompson of the Clean Air Task Force.

THOMPSON: Coal is so abundant, it is so inexpensive, it is so energy-dense, that someone is going to use it. The issue isn’t whether we’re going to have coal or not. The issue is whether we’re going to continue to use it in a way that kills the planet. And we have a choice.

FRAZIER: Back in Waynesburg, Tom Crooks says his biggest fear is the transition period it’ll take to fully incorporate carbon capture. He’s afraid the new EPA mandates will give electric generators a reason to stay away from coal.

CROOKS: When we put this what’s really going to amount to is at least a several year pause in power generators trying to figure out what they should do - they’re not going to sit still, they’re going to go ahead and build a gas plant, or they’re going to go ahead and do something else. But whatever it is, it won’t be coal.

CURWOOD: Coal mining engineer Tom Crooks ending that report from Reid Frazier of the public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth