Deep Seabed Mining

Air Date: Week of May 16, 2014

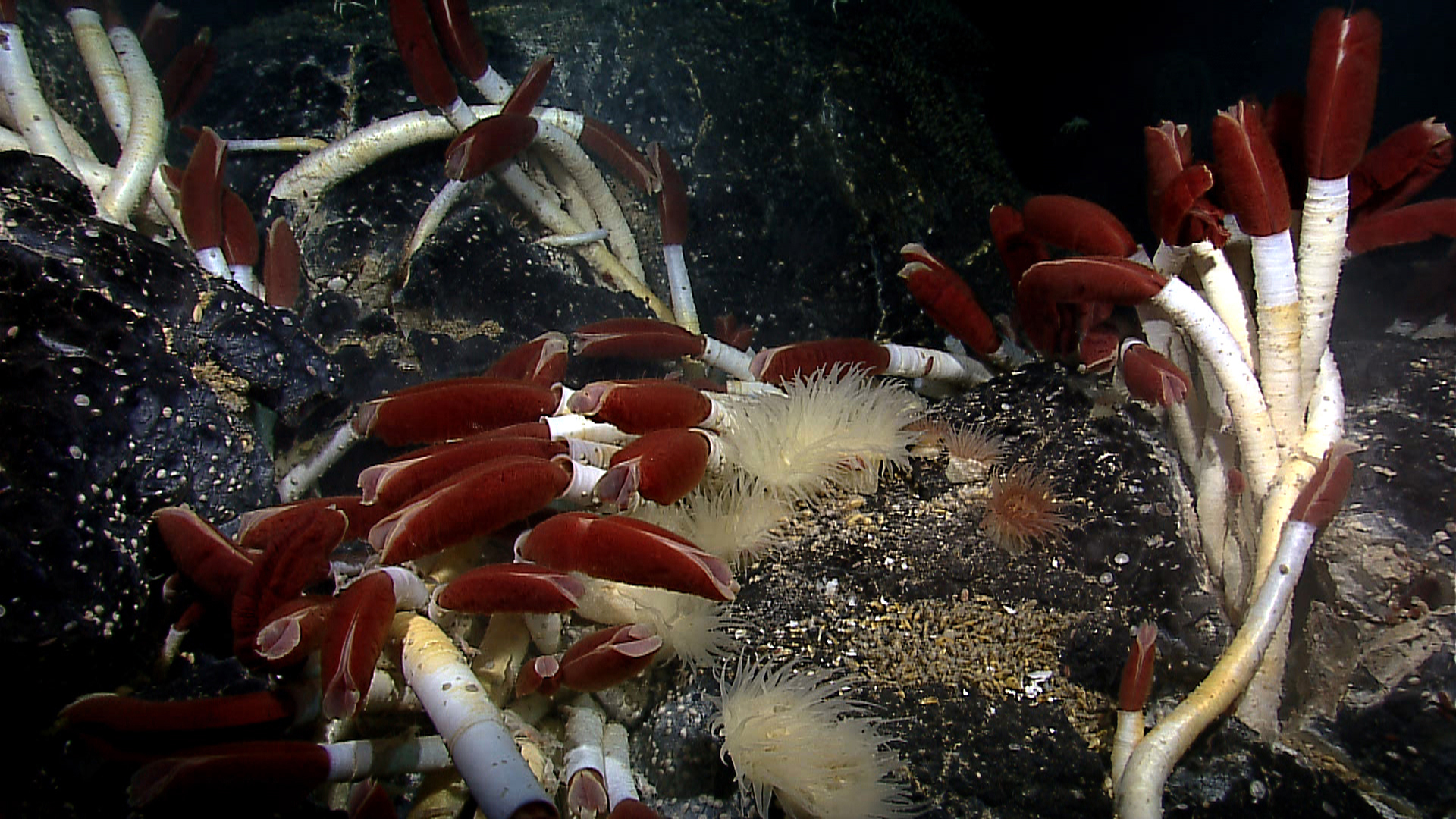

The mineral deposits off Papua New Guinea are located around ocean vents where all sorts of mysterious species flourish, like these tubeworms. (Photo: NOAA)

It sounds futuristic, but a Canadian company has struck a deal with Papua New Guinea to mine gold and other metals from deep beneath the sea. Greenpeace campaigner Richard Page tells host Steve Curwood the project raises concerns about the impact on life in the deep ocean.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Well, if mining coal from under the earth has ancient roots, mining gold from the deep ocean floor may seem like science fiction. But a Canadian mining company has reached an agreement with Papua New Guinea to do just that. The company, Nautilus Minerals, plans to extract copper, gold, and other valuable metals from the seabed, nearly a mile from the surface.

Many worry that this could be devastating to deep ocean ecosystems, and among them is Richard Page, an oceans' campaigner for Greenpeace. He says miners see a treasure trove at the bottom of the ocean.

PAGE: There are sort of three different kinds of mineral deposits in the deep ocean that industry is getting interested in. There are manganese nodules which are found on the abyssal plain of the deep ocean, there are cobalt crusts - mineral rich crusts - on a lot of the underwater mountains or sea mounts spread throughout the ocean, and then you also get these deep sea vents where there are deposits of metals as well. So, sort of three different deep sea environments that could possibly be exploited in the future.

CURWOOD: And where are some of these largest mineral deposits?

PAGE: A lot of them in the Pacific, but there are other areas in the Atlantic that Russia, for instance, is looking at, and also the Indian Ocean too. So they’re pretty well spread around the world’s oceans.

CURWOOD: Now, why Papua New Guinea?

PAGE: Why Papua New Guinea? Well, because it’s a Pacific island-nation that has a large exclusive economic zone surrounded by water, and has an interesting deep sea geology which has these large deposits of metals around vents, and relatively speaking, these would be technologically feasible to exploit and mine these minerals.

A “dandelion” siphonophore lives around ocean vents (photo: NOAA)

CURWOOD: Now, why would Papua New Guinea agree to something like this?

PAGE: Well, obviously Papua New Guinea is a developing nation and wants to develop economically and this is an opportunity for them. However, it’s also a nation highly dependent on the ocean and so a venture like seabed mining isn’t necessarily supported by all the population in Papua New Guinea, and in fact, there are a lot of community groups who are very worried about the agreement made by the government.

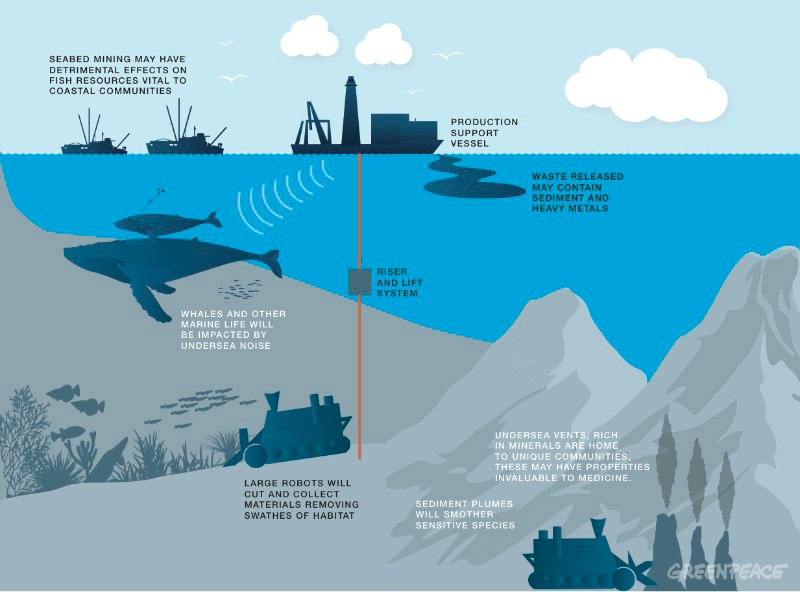

Seabed Mining (Graphic: Greenpeace)

CURWOOD: Now, back in the ’80s and ’90s there was a lot of talk about going for the minerals under the sea. Why is this now back on the table?

PAGE: Yes, so I remember as a boy reading Look and Learn magazine or something similar in saying in the future it would be possible to mine metals and other deep sea minerals. But the technology wasn’t there, and the technology now exists, largely developed from the deep sea oil drilling industry and also the sort of economic conditions are such that there’s a huge demand for precious metals and rare earth metals that are used in all our electronic gear, and so market prices are high, and it’s this combination of demand and the technology, means that there are now companies and countries looking to exploit these minerals.

CURWOOD: Richard, what would the environmental impact of this sort of mining be, do you think?

PAGE: Well, there are lots of potential impacts from deep sea mining. We all know that mining on land has all sorts of environmental impacts. It’s very difficult to contain mine tailings even on land. In the ocean, which, of course, is a fluid environment with all these currents, we can expect widespread pollution, and all sorts of different impacts, everything from smothering of deep sea creatures with sediment, even light pollution in the deep sea will have an impact on all those creatures who have evolved to live in dark environments. So, we’re not sure of the exact impacts, and we may even be destroying or impacting ecosystems that we know very little about. I mean, we know less about the deep sea than we know about the surface of the moon. So it is a big experiment, and quite what those impacts will be we don’t know, which is why Greenpeace is calling for protection measures to be put in place before you ever start an experiment of this kind.

Richard Page (photo: Greenpeace)

CURWOOD: What kind of protection measures would you like to see?

PAGE: Well, our oceans are massively under-protected. Less than three percent of the world’s oceans are either marine protected areas or ocean sanctuaries, and if we’re looking at waters beyond national boundaries then it’s less than one percent. And scientists and governments have all agreed we need to put a global network of ocean sanctuaries in place, they made agreements under the Convention on Biological Diversity and World Summit on Sustainable Development, but they actually haven’t taken the action. What we’re saying is we need to get those kind of measures in place before we start adding to the stresses being put on ocean ecosystems.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, the International Seabed Authority is in charge of allowing people to explore for minerals in the bottom of the ocean. How effective this that organization, do you think?

PAGE: Well, the International Seabed Authority was formed some time ago, before the industry was really technologically possible, and at a time when we knew far less about the oceans than we do now. And so I would say it isn’t really fit for purpose. There are rules it has set which will apply to seabed mining operations in international waters, but those rules don’t take into account what is happening in the water column and other activities. And what we really need is a UN agreement that ties all these different elements together, so we start managing the oceans in a holistic way, so we don’t consider fisheries separate of seabed mining. These impacts may be cumulative. They may be synergistic. We need an overarching framework, if you’d like, to manage our activities under the sea.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think this deal between Nautilus Minerals and Papua New Guinea could be the start of a trend?

PAGE: It’s absolutely the start of a trend. There are lots of places around the world in the deep ocean where such deposits exist, and if this venture is successful then we can expect to see an explosion of deep sea mining. We’ve got something like 19 licenses, I believe, in international waters, and there are other countries and companies looking to do it within the economic zone of very specific islands at the moment. So the Papua New Guinea venture is really the tip of the iceberg, I think.

CURWOOD: Richard Page is an ocean campaigner for Greenpeace. Thanks so much for joining us today.

PAGE: Many thanks.

Links

Read about deep sea mining on the Greenpeace website

Nautilus Minerals explains its seabed mining goals and techniques

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth