Saving Chestnut Trees to Reclaim Mined Mountains

Air Date: Week of May 30, 2014

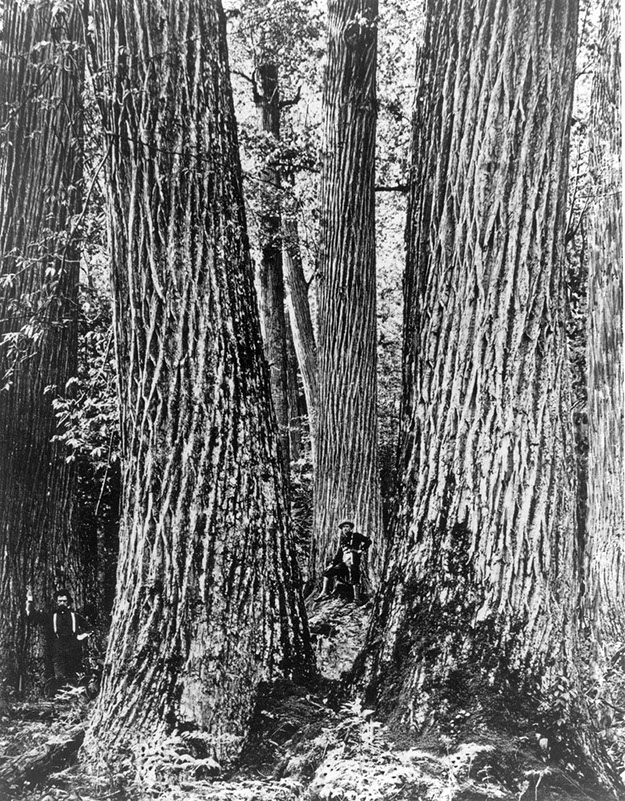

80 foot tall towering American Chestnuts were once a staple of life for people across Appalachia and elsewhere in the Eastern United States. (American Chestnut Foundation)

Soaring American Chestnut trees once covered the Eastern US but a blight nearly wiped them out. Now botanists are breeding a blight resistant chestnut to help restore American forests and reclaim degraded mountaintop removal coal mine sites in Appalachia. Jonna McKone reports.

Transcript

CURWOOD:

“Under a spreading chestnut tree the village smithy stands;

the smith a mighty man is he with large and sinewy hands.”

CURWOOD: So begins the classic poem written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1839, but if Longfellow were alive today he would be hard pressed to find any immense chestnut trees in his hometown of Cambridge, Massachusetts. The mighty American chestnuts that once made up nearly a quarter of eastern forests in the U.S. are now all but gone, thanks to a blight inadvertently imported from Asia in the early 1900s. But now botanists are working to bring back the American chestnut by breeding in resistance to the Asian blight. And nowhere is their work more anticipated than in the hills of Appalachia deforested in the quest for coal. Reporter Jonna McKone has our story.

MCKONE: Thick stands of tall, regal chestnut trees, sometimes called the “Redwoods of the East,” once dominated the forests of the eastern United States. Michael French is a forester with the American Chestnut Foundation.

Mountaintop removal coal mining removes all the soil and vegetation off the surface of a mine to get the coal underground. (bigstockphoto.com)

FRENCH: The old-timers used to the say that when the chestnuts were in bloom in June and July it looked like the ridge tops were covered with snow because of all the chestnut flowers.

MCKONE: These days it looks very different. Not only are the chestnuts gone but from where I’m standing on a mountaintop in Dickenson County, Virginia, the rolling green mountains that stretch into the distance also bear the scars of a history of coal mining. And you can hear the next peak over being torn apart for coal.

[DISTANT RUBBLE FALLING]

HALL: We have some active mountaintop removal just on the next ridge over.

MCKONE: Nathan Hall is reforestation coordinator for Green Forests Work, a non-profit that helps restore former coalmines by planting hardwood trees.

HALL: So there’s rock trucks dumping out big loads of what they call overburden . . . that’s it falling down the mountain right there…. [DISTANT RUBBLE SOUNDS] . . that’s a big chunk of mountain sliding down . .

Chestnuts were once an important source of food for communities in Appalachia. (bigstockphoto.com)

MCKONE: Across Central Appalachia nearly ? of a million acres of mountains have been strip mined for coal - that’s an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. Underground mining started here around the industrial revolution – but it wasn’t until the 1930s that surface mining became widespread. That process strips everything off the surface of a mountain using explosives and heavy equipment to access the coal underground. Dave Fisher, from Kentucky, is a farmer and small business owner who’s worked in coal mining for much of his life.

FISHER: Coal has fed my family; coal has fed generations. All my uncles are coalminers, my grandfather was a coal miner, his grandfather was a coalminer. It’s generational. That’s what we do. That’s who we are around here.

MCKONE: He’s seen first-hand the way mining changes the landscape.

FISHER: You would have huge tracts of land that all the dirt and rock and trees and everything removed and it was flattened out. You’re talking a quarter acre wide, a mile or two long of just big open fields . . .

MCKONE: Fisher says what’s not coal is just in the way.

FISHER: Anything over top of your coal they call it spoil. Cuz it spoils your coal.

MCKONE: As environmental awareness grew in the 1970s several key laws were passed including the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act or SMCRA. The law forced coal companies to fund the clean up of abandoned mines and the reclamation of active mine sites. Al Whitehouse, Director of Reclamation at OSM, the Office of Surface Mining, says early efforts didn’t consider restoring the ecosystem.

WHITEHOUSE: OSM and SMCRA had the belief that a surface mine when reclaimed should be smooth as the baby’s bottom as it were and that compacts it and it wasn’t the kind of land that was really the best for forests.

MCKONE: Whitehouse says the science and policy of restoration has improved -- today mountains must be returned to their ‘approximate’ original contour and fit a designated post-mining land use. But it’s up to private landowners to decide how the land is used after it’s mined.

WHITEHOUSE: The state has a role to make sure that the land capability is back but has no role in dictating what kind of economic interest the landowner pursues. That’s private business. If an old guy wants to raise dairy cows and wants a pasture that’s certainly one of the acceptable post-mining land uses. If that’s what he wants that’s what he’ll have.

MCKONE: At the Dickinson County site the post-mining land use was hay and pastureland. Nathan Hall from Green Forest Works looks out at the old mine.

HALL: Nowadays they’re using a better seed mix than they used to, but for years and years they would intentionally seed out what we see on this site which is Chinese Lespediza, European Fescue and various things that don’t belong here. That’s why we have this alien environment on most of these sites. It almost looks like it’s been painted green on those lower areas.

MCKONE: Kentucky business owner Dave Fisher says the coal companies wanted to reclaim the land as quickly and cheaply as possible.

DAVE FISHER: They just wanted the dirt to stay in place for five years so they could say ‘we done our part, there’s a hillside back and it’s yours.’

MCKONE: Restoration efforts didn’t make use of native plants and failed to understand historical land uses and culture of rural residents.

FISHER: When you look at a place that is undisturbed in this area, the plethora of wildlife and the different nut trees and the different essential plants that we have here – at one people made their living collecting ginseng, and yellow root and bloodroot. And none of that is ever put back on the mined land. Very seldom is any of the hardwood put back.

MCKONE: But hardwood plantings are increasing, thanks to the efforts of universities, environmental groups and landowners. Now some are hoping to restore former mines using native species including the American Chestnut. Fred Hebard is chief scientist with the American Chestnut Foundation. He says the chestnut tree was once a staple of life for people across Appalachia.

HEBARD: The logs provided fencing to keep the cattle out of their gardens and then lumber from cradle to grave. People would be rocked awake in a chestnut cradle, buried in a chestnut coffin and live in a chestnut house and shingled with chestnut bark.

MCKONE: Once some four billion Chestnut Trees blanketed the eastern US but by the end of the 20th century the tree was nearly extinct. An Asian fungus was to blame. In the early 1900's gardens full of exotic and ornamental species were all the rage. With imported plants came pests and fungus, including Cryphonectria parasitica, likely brought over on Asian nursery stock. Within 30 years the fungus spread from Maine to Louisiana killing nearly every towering and defenseless American chestnut in its path.

Though some American chestnuts survived for a few years before succumbing to the blight they all but disappeared from their range. As early as the ’30s scientists were working to bring the tree back from the blight but it wasn’t until the 1980s that scientists started backcrossing the American Chestnut with the Chinese chestnut, a tree that coexisted with the blight for millennia. Using the Chinese tree’s resistance to the fungus, they hope to eventually breed an American tree that can survive the blight. Again Fred Hebard.

Traditionally, mine site reclamation involved planting non-native grasses and few native species. (Green Forests Work)

HEBARD: The only thing you want from a Chinese chestnut is the blight resistance whereas you want to retain all the other characteristics of the American chestnut other than its susceptibility to blight. And you essentially want to throw out everything in the Chinese chestnut other than its resistance.

MCKONE: That’s because the Chinese tree is squat like an apple tree rather than towering and straight like the American tree. The backcrossed chestnuts at the American Chestnut Foundation research farm, in Meadowview, Virginia are essentially 15/16 American and 1/16 Chinese. Pathologist Laura Georgi is introducing the fungus to chestnut trees that contain a mix of Chinese and American genes. She wants to determine the most disease resistant individuals.

[SOUNDS OF MARKING THE TREES]

GEORGI: So this is where they were inoculated. We had two different strains that were inoculated of blight fungus. The lower is the more severe, the upper is the less severe strain. The lower site is a lot of dead tissue. The bark is sunken here. There’s orange and that’s the fungus. Up on top here – this is a little bit better looking.

MCKONE: Using trees bred at the farm, scientists are planting what they expect are blight-resistant seeds and saplings on former and active mines. Again, Michael French.

FRENCH: When you look at the range of the coalfields and the range of American chestnut, the two overlap almost perfectly. So if we can establish founder populations throughout the chestnut’s range on surface mines, it may help us to reach forests that we might not otherwise be able to plant in.

[WALKING]

MCKONE: So far tens of thousands of Chinese-American chestnuts have been planted. Back at the Dickinson County mine site, Michael French and Nathan Hall lead the way along a flat, barren-looking ridgeline to check on a recent planting.

FRENCH: Let’s walk up here actually...I’d like to take a look at some of my chestnuts. I want to see how they’re doing now that they’re leafed out.

MCKONE: The men stop to admire a small sapling.

FRENCH: Isn’t it beautiful? It’s almost two feet tall and only three months old. What do you think?

HALL: That’s from seed?

FRENCH: Yea from seed.

HALL: It’s nice.

FRENCH: There’s a good one there too.

MCKONE: They hope the chestnut population becomes self-sustaining.

FRENCH: So by mixing them in with other northern red oak, yellow poplar, sugar maple, all these species – we’ll be able to see: can the American Chestnuts outcompete the other species to where they’re able to flower and produce seed for squirrels, turkey, blue jay, deer? So that natural processes can continue, evolution, spreading the seed to other areas.

MCKONE: Early data suggests that well over 80 percent of the chestnut trees are surviving. In a few years scientists expect the chestnuts will start producing seeds to grow a second generation of trees. Nathan Hall looks at these mountains and sees unrealized potential.

Chestnuts, once known as the “redwoods of the east,” can grow to 80 feet tall. (American Chestnut Foundation)

HALL: As somebody that grew up here, most of my friends still live here, I see everyday the tremendous need for physical work for people to be engaged in, not only for the money aspect, but also to give people something to do and a sense of cultural identity. Because as the coal mining is moving away from this area, moving out west to Montana and Wyoming, we’re left with a big question of what we do. To me there’s a big opportunity to get people back to work doing restoration and remediation of these lands.

MCKONE: That could mean opportunities for jobs in tree planting, eco-tourism, growing nut and fruit orchards and even biofuel crops on old mines.

HALL: You don’t have anywhere near the economic potential for the region, for these areas that are just covered in a blanket of non-native species.

MCKONE: Dave Fisher is looking to the future as well. He recently started an farm and wants to install solar panels on a former mine.

FISHER: It’s a huge burden upon the people that’s left here after the coal is gone. What are we gonna do with this? It’s something that we really need to address.

MCKONE: The struggle over the costs and spoils of coal production is as deeply rooted in the region’s history as its small towns scattered through the lush hillsides. And the chestnut is part of that history. Reforesting former coalmines with native species is a long-term investment that could eventually mean the snowy white flowers of the American chestnut once more carpet the mountains throughout the eastern US. For Living on Earth, I’m Jonna McKone.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth