California's Water Crisis

Air Date: Week of July 25, 2014

The Steven’s Creek reservoir in Cupertino, California is dry during this drought. (Photo: Gordon; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

To cope with California’s drought, farmers are carefully selecting which crops they plant and overpumping from deep underground aquifers. But as the President of the Pacific Institute, Peter Gleick, tells host Steve Curwood, a viable long-term solution to the growing water crisis requires rethinking priorities and conserving much more water.

Transcript

CURWOOD: So come December, there may be relief for California’s record-breaking drought, but for now, it’s about as bad as anyone can remember. Peter Gleick is President of the Pacific Institute in Oakland, California, and a fresh water expert. Welcome to Living on Earth.

GLEICK: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So, let's talk about agriculture. California puts a lot of food on our tables here in America. What's been the impact so far of the drought on the agricultural sector and where are things heading?

GLEICK: So, 80 percent of the water that Californians consume goes to the agricultural sector, and the Central Valley is a fantastic place to grow food. We grow a lot of the nation’s fruits and vegetables. The overall current estimate is that impact to the agricultural community will be perhaps a few billion dollars this year and maybe a few tens of thousands of jobs, which is in some sense is a big impact, but it's a $40 billion ag. economy out of a $2 trillion statewide economy.

CURWOOD: Now how are the farmers coping exactly with the shortages?

GLEICK: What we do when we don't have surface water in California is we over-pump groundwater, and so a lot of the farmers in the Central Valley this year are looking to groundwater to make up surface water shortfalls. One of the reasons the impacts may not be too bad this year economically is precisely because we're over-drafting groundwater. We're looking at that groundwater pool as a way to make up some of the surface water shortages, and we can do that in the short run, but that's not sustainable in the long run. Groundwater levels are dropping and when groundwater levels drop we see decreases in flows in some of our streams that are also dependent on groundwater flows in the dry part of the year. And the reality, of course, is that not every farmer can pump groundwater—only those who can really afford to drill deeper and deeper, more and more expensive wells have that as an option. And some farmers will benefit and some farmers will lose.

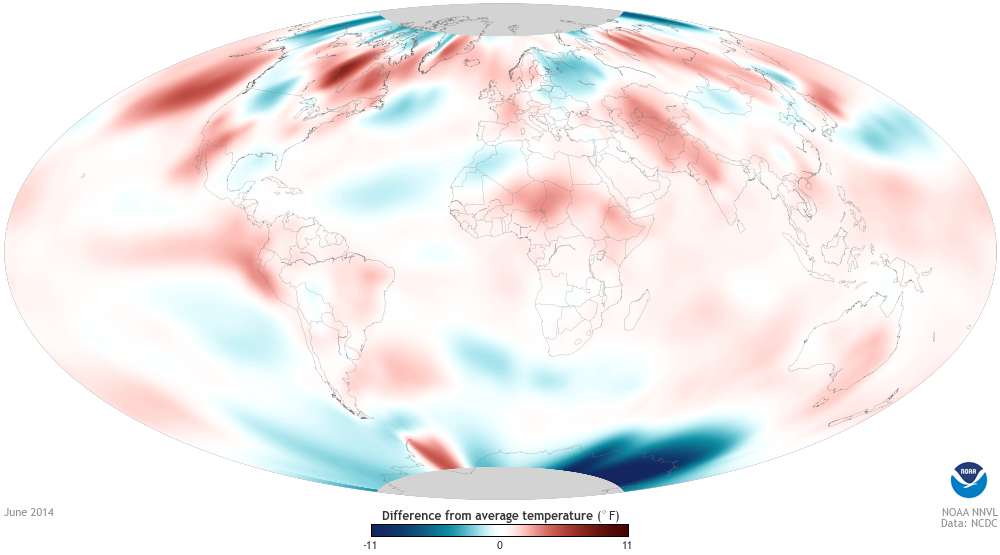

NOAA’s report shows the difference in this year’s June temperature. (Photo: National Ocean and Atmospheric Association)

CURWOOD: I understand that there've actually been drops in the level of the soil in the Central Valley.

GLEICK: Well, interestingly, this has been a problem for decades. You know, 50 or 60 years ago, when groundwater was over-pumped, we saw very, very significant subsidence on the order of tens or even more feet of subsidence. There's some remarkable old photographs from the Central Valley years and years ago showing how far land levels have dropped. We solved that problem in the 70s and 80s and 90s with deliveries of surface water, and groundwater overdraft decreased. But it's increasing again: we are seeing subsidence on the order of tens of feet and potentially more as the drought continues.

CURWOOD: Now in your view, Peter Gleick, what crops does it make sense to grow in California given the tight water situation, the perennial tight water situation, and which ones maybe shouldn't be grown there?

Effect of the Drought on the Uvas Reservoir in California. (Photo: Don Debold; Creative Commons 2.0)

GLEICK: Crop decisions are a complicated thing. It's not just how much water is available, but in bad droughts, what we see is farmers shifting from crops that they can fallow for year—they may let field crops go for a year—but they don't want to let their trees dry up and die. And so during a drought we see farmers protecting trees, investments in orchards and fruits and nut crops, even if they can't give them their full amount of water, they don't want those trees to die. Those are a decade-long investment. And so what we see is less planting of cotton and wheat, less planting of rice, less planting of alfalfa, and protection of some of these higher value fruits and nut crops.

CURWOOD: California is naturally actually a pretty dry place. There are massive water projects to bring water there from other places. How did we come to have so much human settlement and agriculture in the Golden State given the sort of intrinsic lack of water for California?

GLEICK: California is a complicated place. You know, we have a lot of water in the north and a lot of water in the mountains. The population has settled in the coasts and in the south where there's less water; because of that we've built a massive infrastructure. We've built systems to store water in the wet season so we can use it in the dry seasons and aqueducts so we can move water from the north in the mountains to the south and the Central Valley and the coasts where we want it. And our development patterns have been such that, the assumption's always been that we can live wherever we want and we'll bring the water to where the people are. I think that can't continue. I think we’re going to have to have some serious conversations about the kinds of development we want and permit in the future. We're going to have to have serious conversations about whether it makes sense to grow certain kinds of crops in an incredibly arid environment. I think we'll continue to have a strong agricultural economy. We'll continue to have big populations in dry areas, but we have to seriously reconsider the systems that we put in place and manage to satisfy those demands.

A sign on a lawn in Sacramento (Photo: Kevin Cortopassi; Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: We talked a lot about agriculture. What about the built-environment: residential and commercial water use? How can we cut down on that?

GLEICK: About 20 percent of the water that Californians use goes to our homes and our industry and our commercial establishments. We've made a lot of progress, as we have in the agricultural sector in improving efficiency in those water uses, but there's still lots of inefficient water uses in our urban centers. And we still use a tremendous amount of water for outdoor landscaping. We pretend as though we have an old English climate and can have English-style lawns, but we're in an arid environment, and we need to get rid of, frankly, inefficient lawns and inefficient gardens. I got rid of all the lawn in my house, and I still have a beautiful garden, and my water use is half the state per capita average of the average person in California, and even I could save more water.

Much of household water-use in California comes from watering lawns. (Photo: Diego V; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: And I gather you're growing more than crabgrass?

GLEICK: Oh, no. We're not growing any crabgrass.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

GLEICK: Crabgrass is a terrible user of water, and it's ugly. We have a beautiful garden: we have flowers; we have native plants; we have blueberries and strawberries, and yet our water use is half the state average.

CURWOOD: What if the phone rang—it's Governor Jerry Brown. He says, "Peter Gleick, you are now the water Czar for the state of California." What are the three or four things you'd do if you had that kind of power?

GLEICK: The solutions to our water problems are not the solutions that we looked at in the 20th century. We're running into peak water limits. There is no more untapped, unallocated water in the state, and the reality is, we've given away far more water than nature naturally provides. So our options are fairly limited, but we do have options, and the key things that we need to be doing now are looking at the potential for more efficient use in our cities and more efficient use on our farms.

Farmers prioritize high-value tree crops like almonds during times of drought. (Photo: Marc; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

There's a lot more that we can do on conservation and efficiency. But there are also a couple of new supply options that we really ought to be considering seriously. We ought to be exploring and expanding the use of treated wastewater. We use potable water to flush our toilets and to water our lawns, not just for drinking, and yet there is very high-quality wastewater available. We collect a lot of wastewater; we treat it with very high standard and typically we throw it away. Let's put that supply of water to use. And similarly we ought to be expanding our efforts to capture and use storm water.

There's a lot of potential for wastewater reuse, storm water capture and reuse as new supply options and improvements in conservation and efficiency. And those four options alone could produce a tremendous amount of new water for the state of California, and that's where we ought to be going now.

CURWOOD: Now, what do you think the American West is going to look like in 50 years given what we’re seeing now with drought increase?

GLEICK: Well, especially with climate change, I think we're going to see higher and higher temperatures. We're going to see more extreme events in the western U.S. The climate models suggest unfortunately that the Southwest is going to get drier, not wetter, which is the opposite of what we would like if we had any choice in the matter. I think there will be fundamental changes in agriculture. I think we're not to be able to afford to spend as much water in the west on agriculture as we currently do. And potentially I think we're going to see the Midwest and the Northeast begin to advertise, hey, come back home. There's not as much water in the Southwest, and it's hotter and hotter in the Southwest, and our climate is increasingly attractive. And that's going to be a turnaround from the old days when the Southwest advertised and drew people from the Midwest and from the North because of their more attractive climate.

CURWOOD: Goodbye. Go west, young man, huh?

GLEICK: I think so. I think we're going to see more and more of that.

CURWOOD: Well, what, a fifth of the world's fresh surface water is in the Great Lakes.

Peter Gleick is the Director of the Pacific Institute in Oakland. (Photo: Oakland Institute)

GLEICK: We're already seeing conversations from some communities in the Midwest that perhaps they can advertise that their water availability and their water quality and their reliability as a way to draw industry and residents back to the region.

GLEICK: So far our discussion has really just focused on people and our needs from water. What about the rest of the natural world?

CURWOOD: We know we've taken far too much water out of the environment. Fisheries are collapsing; ecosystems are collapsing. There've been more and more efforts on the legal front and on the educational front and on the policy front to try and restore ecosystem health and restore some commitments of water for the environment. But during a drought, we measure impact on farmers; we measure impacts on industry. We're not really good at measuring impacts on fisheries and ecosystems, and yet some of the worst impacts historically have been, for example, on the salmon fisheries and the salmon runs in the state of California during drought. We had better not give up on the environment during droughts in order to restore a little more alfalfa production or cotton production the Central Valley, or to save our lawns in our cities. I think that would be a big mistake.

CURWOOD: Peter Gleick is President of the Pacific Institute. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

GLEICK: Well, thanks for having me on. It's always a pleasure.

Links

The Pacific Institute published a paper with four solutions to drought.

The Pacific Institute runs the website, California Drought.

The New York Times’ interactive map of the drought facing the U.S.

Peter Gleick is the author of the book A 21st Century U.S. Water Policy.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth