What A Howling Wolf Howl Says

Air Date: Week of May 8, 2015

A wolf from Yellowstone's Druid Pack mid-howl (Photo: NPS Photo)

When a wolf howls in Yellowstone’s snowy landscape, a howling chorus responds. But in the spring, the wolves grow quieter as they raise pups. Now researchers understand how wolf calls change with the seasons, and hope to answer the tougher question of what the howls actually mean. The park’s reporter-in-residence, Jennifer Jerrett, has the story.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Well, Jennifer Jerrett is still following the wolves of Yellowstone, and she says that they literally change their tune come spring. And there’s new research on the nature and meaning of how and what the wolves are communicating. Here’s her story.

JERRETT: There is nothing like springtime in Yellowstone. After the long, snowy, hush of winter, the spring season around here seems to erupt in layers and layers of sound.

[SPRING BIRDSONG

JERRETT: But unlike most of the other animals in the park, wolves tend to become a little quieter in the spring.

[BIRDS; WOLVES HOWLING]

JERRETT: Researchers in the park recently discovered that there is a seasonal cycle to those howls.

[HOWLING FADES]

JERRETT: Biologist Doug Smith is the project leader for all of the wolf research that takes place in Yellowstone National Park. He says that if you’re a wolf in Yellowstone, you still howl in the spring…

SMITH: … but you howl less, you only howl when you need to and you’re only howling to your pack mates. As the summer grows old, you start howling more and more and so now you start howling to your neighbors, your enemies, and it increases through the fall and winter. That’s the seasonal cycle.

Wolf pups in spring (Photo: NPS Photo)

JERRETT: The seasonal cycle peaks in February which tracks right along with the breeding season in Yellowstone. And there’s a lot of howling back and forth between neighboring or rival wolf packs.

SMITH: Wolves are ferociously territorial, and so they howl to others to say ‘Hey I’m here, stay out.’

JERRETT: But in the spring, when wolves start establishing den sites to raise pups, everything changes.

SMITH: So what appears to be happening during the denning season is that howling for territorial purposes goes away. You stop communicating to your neighbors. So what we’ve noticed--what doesn’t go away--is howling to your pack mates, to your family members.

JERRETT: So while there’s less howling overall in the spring and summer, the call-and-response that does go on is almost entirely within pack. Doug has been studying wolves for 35 years. He explains what might be happening.

SMITH: In the winter the pack’s all together and they travel widely, they go everywhere. When they have those pups, wham! An anchor gets thrown in, they become your ball and chain. And wolves need to carry out their business, but they also need to care for their pups. So they leave the pups at the den and they split up. Well that presents a problem of how you coordinate activities, how do you communicate, how do you find each other. Well, you howl.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

SMITH: So what’s so important about that story is that was a previously unknown story. Now enter Yellowstone.

JERRETT: The only way that the research team working in Yellowstone was able to tease apart this seasonality – more howling that tends to be territorial in the fall & winter, less howling that’s more family-focused during spring & summer -- is because when it comes to wolf research, Yellowstone’s landscape is unique. There’s a lot of open country in the park. So you can see the wolves – see what they do when they howl and this is what provides the context for understanding howling.

You never forget your first wolf in the wild. (Photo: NPS Photo)

SMITH: Through this breakthrough of being able to see and hear and determine the context --

that’s how John and Mary Theberge -- that’s the couple that’s doing this research – and they were able to quantify this is a howl for the away game and this is a howl for the home game. And that has been leaps and bounds of progress in terms of understanding why wolves howl.

JERRETT: To dig in to a scientific answer, I called John Theberge at his home, way up in the mountains of British Colombia. I talked with him about this aspect of his work in Yellowstone that is just getting underway: What do the howls mean?

THEBERGE: And that’s the really slippery slope. (laughs) It’s a complex topic because wolves are complex. The theories of animal communication are complex. The mind of the wolf is complex and one of the most perplexing things is that however we try to interpret another animal’s behavior we do so through our minds

JERRETT: Which makes it tricky—even for researchers—to figure out whether there’s any real meaning or intention behind different howls.

SMITH: When you sit and you listen to that lone wolf howl, almost moaning, it just doesn’t sound, …it seems to mean so much more to the individual wolf: You know, this animal is sad, it’s lonely. And we’re trying to really figure out what does that wolf howl really mean.

[MOURNFUL WOLF HOWLING]

JERRETT: Even if we don’t yet know what it means, the call of the wolf is an iconic and unforgettable sound that can send chills up the spine. There’s a saying around Yellowstone that you never forget your first wolf in the wild and that’s certainly true for Doug Smith.

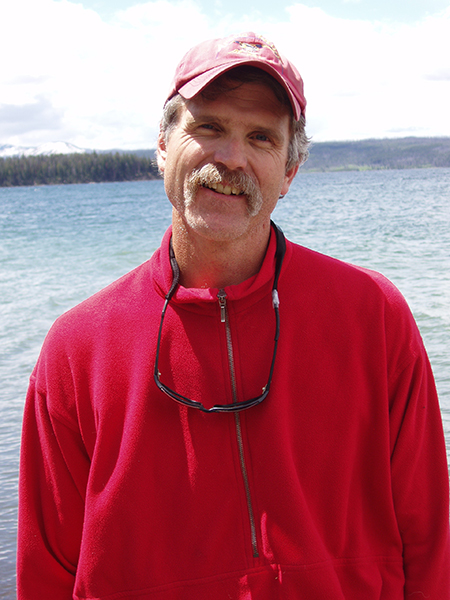

Doug Smith is a wolf biologist and the project leader for wolf restoration program in Yellowstone National Park. (Photo: NPS Photo)

SMITH: The first time in the wild I heard a wolf howl was on Isle Royal. It was the middle of the night, I was standing outside the tent in my underpants - the bugs weren’t too bad - and the moon was shining. Then way off in the darkness of the night a wolf howled.

[DISTANT WOLF HOWL]

It came from oh gee a mile or two out, and right at the end when I swear, it came in so close I could hear the sticks snapping, the howls were booming in -- it was like in the palm of your hands -- and that wolf never stepped in to the light of the moon and I never saw it.

[WOLF HOWLS NEARBY]

That was nature at its best.

JERRETT: There are a lot of people like Doug in this park. People come from all over the world to see and hear wild wolves in Yellowstone. And this latest research into wolf ecology, communication, and behavior, offers an opportunity to move further, beyond seeing and hearing, to take another tiny step closer toward understanding the mind of the wolf.

For Living on Earth, I’m Jennifer Jerrett in Yellowstone National Park.

CURWOOD: Jennifer’s story was made in conjunction with the Montana State University Library’s Acoustic Atlas project. Thanks also to the Yellowstone Association and the Yellowstone Park Foundation.

Links

More on the wolves in Yellowstone via National Park Services

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth