Restoring Giant Kelp Forests

Air Date: Week of July 10, 2015

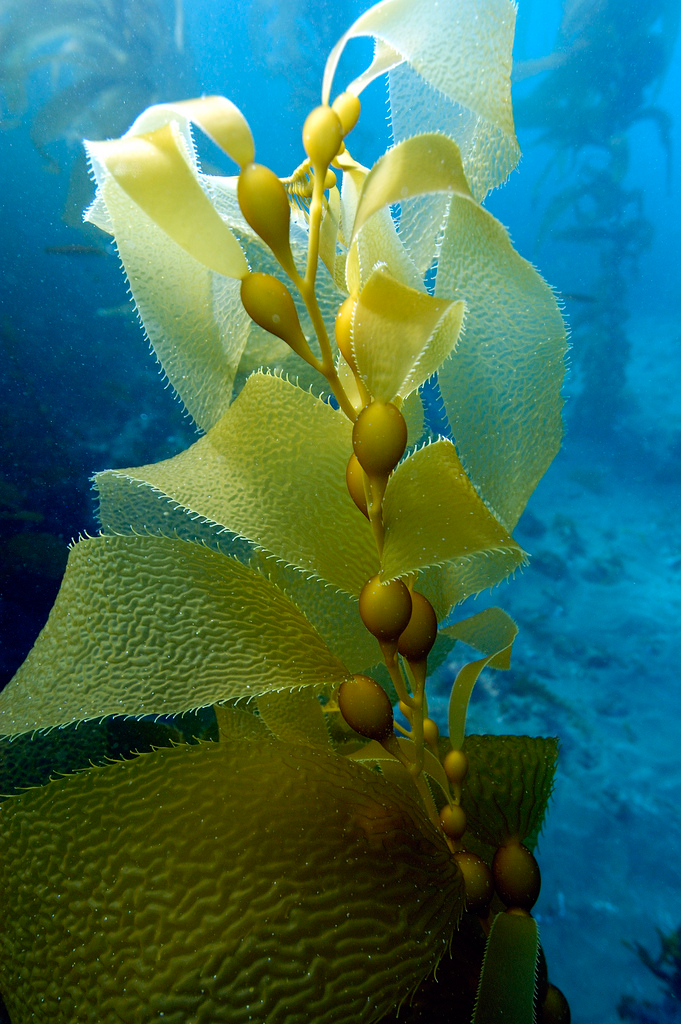

Kelp forests can grow up to 18 inches per day and prefer cold, nutrient-rich waters. (Photo: NOAA; CC government work)

California’s giant kelp forests were mostly wiped out by ecosystem imbalances, but a decades-long citizen science effort has helped restore them. Host Steve Curwood speaks with marine biologist Nancy Caruso about the fragile ecosystem, the restoration she led, and California’s majestic kelp forests.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. In late August of 2014, huge mounds of the largest type of seaweed in our oceans, kelp, started piling up on Laguna Beach in Southern California. Tourists and would be sun-worshippers were not happy as the smelly thick brown ribbons took over the sand. Scientists estimated that hurricanes had ripped as much as 95 percent of the offshore kelp forest from the ocean floor nearby. But marine biologist Nancy Caruso says all [of] that fly-ridden gunk on the beach is actually a sign of a healthy underwater ecosystem. Caruso is founder of the nonprofit Get Inspired!, which organizes volunteers and students to restore the kelp forests, and she joins us from Garden Grove, California. Welcome to Living on Earth.

CARUSO: Thank you very much; I appreciate that.

CURWOOD: So explain to me exactly why all that kelp washing ashore is a sign, or could be a sign, of a thriving ecosystem?

CARUSO: Well, 12 years ago, myself and a group of students and volunteers all started a project to restore the kelp forests off of Orange County's coast. We've been kind of waiting as our restoration efforts appear to be successful. The real test comes when something like a hurricane or big swells coming out of the south show up and rip out all of our kelp, which is a natural occurrence, kind of like forest fires in the forest, where the forest is destroyed so to speak, but new life can start.

Kelp forests can be seen along much of the west coast of North America. Kelp are large brown algae that live in cool, relatively shallow waters close to the shore. They grow in dense groupings much like a forest on land. (Photo: NOAA’s National Ocean Service; CC BY 2.0)

So big holes have been created in the canopy of the forest and new life can grow from the bottom up, and so if we see this happen, which we're seeing right now, the kelp returns immediately after this event, then we know that our restoration efforts are successful, and after 30 years of our local ecosystem not having healthy kelp forests, we can rest assured that it's now restored and everything is back to normal again.

CURWOOD: For a moment let's talk about kelp itself. What does it look like and what is it taste like?

CARUSO: Well it looks like trees underwater, if you can imagine. Imagine being in a cathedral with stained glass windows and there's light dancing through the stained glass windows onto the floor, and that's what it looks like underwater in a kelp forest—these beautiful amber blades that the water...the sunlight, rather, dances through on the bottom of the ocean and creates beautiful light patterns. And as far as how it tastes, well, that's really up to the animal that's eating it, but for humans we actually eat it as well. Kelp contains a compound called alginate and it's used as an emulsifying and thickening agent so it binds things together and it makes things creamy and smooth. So if you ever had a diet salad dressing, for instance, if you take the fat out of it then it's not really creamy anymore, but you can add alginate back into it and that will give it the creamy texture. So we've eaten a lot in alginate in our lives, we're just not familiar with the fact that we're all intimately tied to giant kelp.

CURWOOD: How big are these giant kelp?

Get Inspired! Tour: Nancy Caruso and Pacifica High School students paddle out to evaluate the restored kelp forest. (Photo: courtesy of Nancy Caruso)

CARUSO: That's a good question. They're not called giant for nothing. So they can grow up to about 110 feet tall and they often, however, grow in water that's less than 30 feet deep. So the kelp forest grows up to the surface, then we have another 80 feet of kelp that just spreads out along the surface and creates what's called a canopy. And the canopy also provides cover for those fish that are swimming up and down our coast following the plankton, following the currents, and they can hide underneath that canopy from pelicans and other diving birds that are just waiting to eat them.

CURWOOD: So, Nancy, talk to me about how you actually restore kelp. I'm envisioning you strapping on a tank and mask and flippers and everything and going down there to plant little kelp seeds.

CARUSO: It was actually quite an effort because I had the help of 5,000 students from ages 11 to 18 as well as 250 skilled volunteer divers, and we planted this kelp in 15 different areas in Orange County. There's a spot down in Dana Point. It's the only kelp forest that was left in Orange County so we would collect the reproductive blades from those kelp plants, and I would take them into the classrooms for the students to clean them and we would actually stress them out overnight. We would leave them out of water in the refrigerator, kind covered with paper towels, and then the next morning we would put them back in the ice-cold seawater and the kelp blade would release millions of spores. They're microscopic. They're 400 times smaller than you can see, and we would get these spores to land on small little bathroom tiles, and then we would raise them in the classrooms in little nurseries that we built out of Home Depot parts and fittings, and the kids would raise them for about four months, just to the point where you can see them with your naked eye and then we would take these tiles out in the ocean.

A diver swims among giant kelp, which can grow as tall as 110 ft. (Photo: Ed Bierman, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

After the kids learned all the ecology and biology and how the kelp disappeared, how to protect it, they became warriors for the kelp and then the volunteers would take it out into the ocean and using a rubber band really simply attach the tile to the reef. There would be thousands of kelp spores growing on each tile, and they would all outcompete each other and its root system, called the holdfast, would just grow off of the tile and attach itself to the reef, and the tile was nonleaded and unglazed so it could actually biodegrade - a rubber band is biodegradable - and there is kelp out there still that has started off from our tiles, so it's really gratifying to see that.

CURWOOD: Ah, you are the grandmother of how much kelp?

CARUSO: A whole lot!

CURWOOD: So what did the kelp forest look like before you started this restoration effort? Why did they disappear?

CARUSO: Well, it's actually a long process to collapse an ecosystem. We used to have furry little mammals living down here in Southern California called the southern sea otter, and they've been gone since the 1840s when the last otter was killed in southern California. Without the sea otter, things immediately started to go out of balance because the sea otter is kind of the top scavenger, I guess, in the oceans here and it keeps all of the animals that eat the kelp in place. So the otter disappeared and therefore the sea urchin populations got out of whack and we ended up with a lot of sea urchins on the reef and they basically mowed down the kelp forest.

So it started with the demise of the otter and then paving over the surfaces of southern California to where we don't have...or we have lots of runoff creating cloudier turbid waters off of our coast, and kelp likes sunlight. It is actually an algae, so it produces food for itself through photosynthesis, and it can't grow in deeper waters anymore. And the third and last straw for the demise of our kelp forests was actually the El Niño event of 1983, and that kind of like this year ripped out all of the kelp that was left in the area, however, there was so many other pressures on it, it never actually made it back.

Sea otters often tangle themselves up in kelp while they’re sleeping. Sea otters are crucial to a healthy kelp forest; they eat sea urchins and other invertebrates that feed on giant kelp. (Photo: Mike Baird; Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the responsibility that we as people have to restore kelp forests since we contributed to their decline.

CARUSO: Well, first and foremost, the number one thing that we can do is to stop runoff from going into the ocean. We don't get a lot of rain here, so every time it rains or whenever you're overwatering your lawn or washing your car, that water goes down our sidewalks, down our streets, washes over everything that's on the streets and sidewalks into the sewer system and directly into the ocean in most cases. And so trying to eliminate that runoff and the things that are on the streets and on the sidewalks that go with the water into the ocean is critically important and something that everybody can do on a daily basis.

CURWOOD: So, Nancy, I've got to tell you, I spent time near Capetown, South Africa, where there's a huge kelp forest offshore, and that means that on the beach there are piles and piles of this big huge kelp. And it's kind of smelly. It's got a lot of flies; people feel annoyed that they can't use that part of the beach. How do you cope with that? People come to southern California they want to, you know, go down to the beach and here you've got this stuff.

Among a few factors contributing to the decline in kelp is runoff from California’s agricultural sector. (Photo: Craig Jewell, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CARUSO: Well, kelp actually has a purpose when it washes up on the beach. It doesn't just end its life when it gets pulled off of the reef. Inside that massive wrangled tangled kelp, there're literally hundreds of animals living. So you'll see kids often going through the plant looking for starfish, crabs, lobsters and sea urchins and usually there's a chance actually for it to get washed back out again. And this is just like the process that I explained where we stressed the kelp out in the classrooms to get it to grow. We would take it out of the ocean and stress it out, keeping it moist and cool, which it does on the beaches, it's all wrapped up and stays moist and it shades itself, and then when the tide comes up again it can get washed back out into the cold water of the ocean and it'll reproduce. But also all those animals that get washed up on the beach inside the wrangled tangled kelp become a food source for shorebirds that live along our coast, and also there's a really special fish here in southern California called the Grunion, and it only spawns on our beaches, not in the water but actually in the sand, and it only does it certain times during the year and it's a big event, everybody goes out to watch it, it's at night you know during certain phases of the moon, and the kelp can actually keep the sand moist on top of the eggs of these Grunion, so there's a whole ecosystem that occurs when the kelp gets washed up.

CURWOOD: What about the tourists? How does all the kelp affect the tourism?

CARUSO: Well, when you go to a forest and there's leaves all over the ground, most people don't complain about that because they know that that's a natural process of leaves falling on the ground. So it's really about educating people what the kelp forest ecosystem is, and why it's important, and the whole entire cycle, not just out in the ocean and underwater, that slimy stuff that grabs my ankles when I swim over it, but it's also part of the beach, coastal ecosystem.

Nancy Caruso is a marine biologist and the founder of Get Inspired!, a program that performs kelp restoration in California. (Photo: courtesy of Nancy Caruso)

CURWOOD: And it has these tiny little crabs and periwinkles and stuff running around inside it.

CARUSO: Umm hmm. Exactly.

CURWOOD: So, you're so excited about kelp. When did you fall in love with kelp?

CARUSO: Well, I wanted to be a marine biologist since I was 10 years old in Virginia and ended up going to school in Florida and just by happenstance I made it out here to California and worked for a local public aquarium and that's where I really, I mean as a kid I watched Jacques Cousteau diving in the kelp forest in the Catalina Island in southern California and I often thought wow that's so cool like I wish I could go there, and when I finally ended up here I was just taken in by their majesty and their beauty.

CURWOOD: And shocked then that off of Orange County they were gone.

CARUSO: Yeah. The beautiful thing was that I was looking to do work within the community. I wanted to work with people and get people excited about doing conservation work, and then this opportunity to start up the kelp program became available to me and it was exactly what I wanted to do. I've kind of been able to become a messenger for the kelp and to give it a voice so to speak, so I'll keep an eye on it for as long as I can.

CURWOOD: Nancy Caruso is the Founder of Get Inspired! It's a nonprofit that gets Southern California residents involved in kelp forest restoration. Nancy, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

CARUSO: Thank you so very much.

Links

The Get Inspired! Website and photo gallery

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth