A Prayer to Share Earth as a Commons

Air Date: Week of September 11, 2015

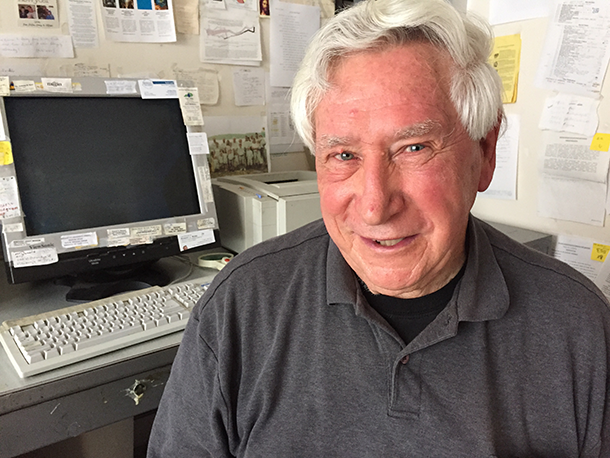

Father Al Fritsch, S.J. is the Director of Earth Healing, a website dedicated to providing daily reflections on simple living and matters of faith. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

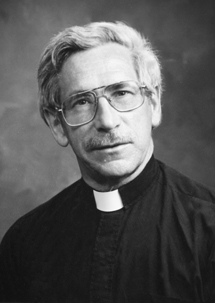

Jesuit Priest Albert Fritsch has long called for “Earth Healing” through his website and work with advocacy groups in both Washington DC and rural Kentucky. Now, Father Fritsch speaks with host Steve Curwood about how he’s using his chemistry background to lead his parish in discussions about Pope Francis’s environmental encyclical, emphasizing the moral and religious relevance of protecting the Earth’s resources for all people.

Transcript

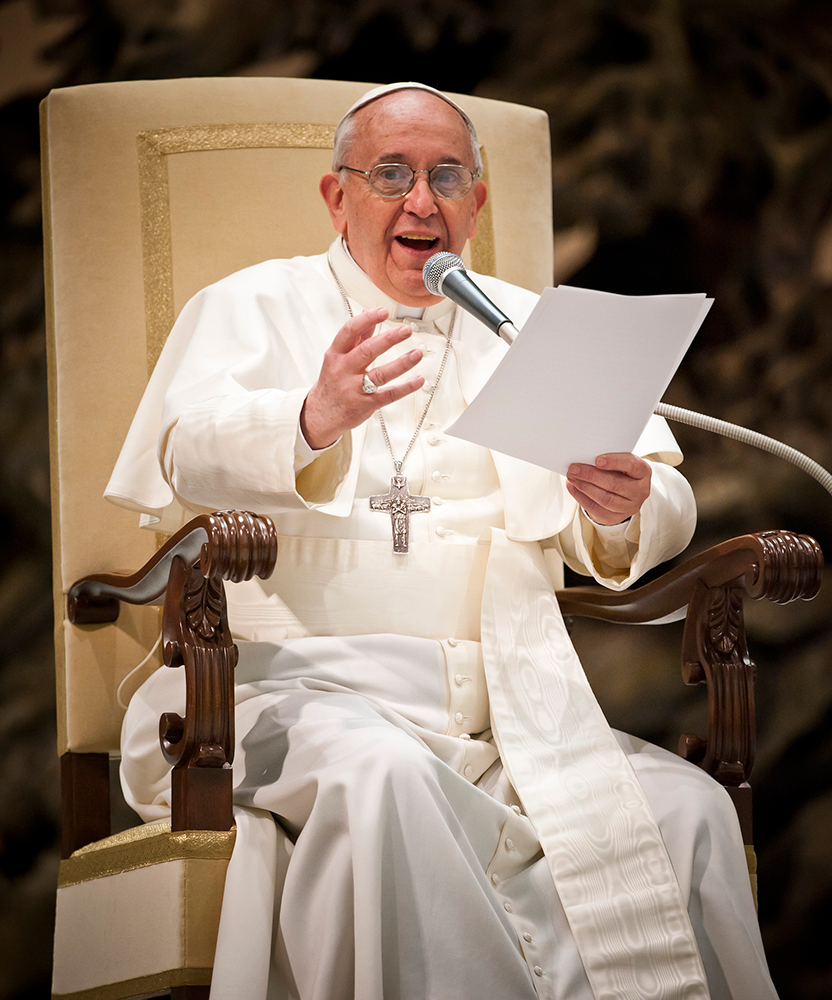

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Pope Francis, the charismatic leader of the Roman Catholic Church, is coming to the US later this month for an eagerly awaited visit. The Pope’s recent encyclical Laudato Si frames climate change as an urgent and moral issue and is driving conversations in and out of the church. The Pope’s environmental concerns go back a long way, according to the web manager for EarthHealing.info. Earth Healing focuses on Catholic care for creation, and the manager says the pontiff visited the website before his election as Pope. And the website’s creator, Father Albert Fritsch like the Pope, is a Jesuit priest with training in chemistry. I spoke with Father Albert at the rectory of the Parish of Saint Elizabeth’s in Ravenna Kentucky, which is in one of the poorest counties in the US, not far from where he grew up on a farm.

FRITSCH: Well, my father was an extremely good farmer, and we took these very poor farms and turned them into very productive landscape, even crushing our limestone rock which was there and spreading it out, and of course we had rotation of crops, tobacco which was the normal crop along with mixed corn, hay and wheat. And that's what we grew on our farm along with vegetables and fruits and therefore we were mostly self-sufficient, and we never sent anything outside the farm as waste. We fed foodstuffs that were left over to the hogs and the chickens, everything was used up in our own area, what we had.

CURWOOD: So you decided to leave the farm. Where did you go?

FRITSCH: I went to college, went to Xavier in Cincinnati. It was a very good school. I got a undergrad and masters degree there in chemistry.

Father Fritsch grew up on a farm in rural Kentucky where his family grew tobacco, corn, hay, and wheat, along with vegetables and fruits. (Photo: Todd Shoemake, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And you got a doctorate as well in Chemistry.

FRITSCH: Yes, I did, at Fordham, and went on to do a post-doctorate at the University of Texas.

CURWOOD: So what got you interested in the priesthood?

FRITSCH: Well, I saw people I really liked very much who were Jesuits. I also had a great problem with what chemistry usually involves and that is to go to a commercial institution, work for a company. I didn't like the idea of that. Academics - well that was good but I was hoping to do something that would apply the great gifts that we have with chemistry for the betterment of society especially for the poor.

CURWOOD: So what was the draw of the priesthood? Now you have a doctorate in chemistry, you're concerned about how people use chemistry, and you feel yourself being drawn to the priesthood and the Jesuit priesthood at that.

A coal train rolls by a few blocks from Father Fritsch’s parish in Ravenna, KY. Father Fritsch’s concern for the effects of coal mining on the landscape where he was raised eventually brought him back to rural Kentucky. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

FRITSCH: Well, it was to save our own souls, of course, is the first thing that we do it for, but also immediately it is to help all other people in some way, and I didn't see that a lot of the people who were connected to career jobs and trying to make a lot of profit in the work which they did, I didn't see that that was really the calling for what I was doing myself or for the field itself. I felt that science, if you look back upon it, a lot of people over a long period of history had contributed a lot to making chemistry what it was, and in seeing this it struck me that here is a Commons that we all have, but suddenly it's been picked up by some and used and made a fortune out. And why should it, because was part of a Commons that we all had.

CURWOOD: Now, you finish up your doctorate and you decide that you're going to, well, help people, and you start to do some rather practical environmental things. What kinds of things did you do?

FRITSCH: Well, I began the work after my studies and I was still at University of Texas, met a young fellow in a march that we were on, and he was going to work with Ralph Nader as one of his hot shots for the summer, and I asked him, "Well,” I said “I've been looking for something that would be more of a public interest field. Would you ask Ralph if he needed somebody like that." So he did, came back the next week and said, "Yes, go and have a connection with him and see if you can work out something." We started there at the Center for the Study of Responsive Law in 1970 and the next year we set up the Center for Science of Public Interest, with two other scientists who were working with Nader, and that field I stayed with in Washington for seven years and then decided that we really needed a branch that came closer to the poor of the country and so I had a Appalachia Science of the Public Interest which exists to this day, and so Ralph Nader has been very helpful to us in helping us get donations and things even to this day and so we've been friends ever since.

A strong supporter of Pope Francis’s encyclical on the environment, Father Fritsch hosts a series of discussions with his parishioners on its teachings. (Photo: Catholic Church England and Wales, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So you decided when you were in Washington that you would come back to Appalachia where you were born and raised, to have a ministry here. Why?

FRITSCH: Why did I come back? Well, one of the first grants that we had received was from Jay Rockefeller who then the treasurer over at West Virginia and he asked us to work on some surface mine issues for the state of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Kentucky, the different regulations related to them. And so from the beginning I began to see that strip mining was really affecting parts of Kentucky where I was from and we did that type of work in Washington for a period of time, but we moved back because Washington DC is surrounded by seven of the wealthier counties of the country and yet if were going to make a simple lifestyle that people have to go to and live, we better go back to where the poor people are and see if the challenge can’t be done there first. That's why I came back.

CURWOOD: So what was it like to come back here?

FRITSCH: Well people were interested in the fact that we were trying to do a simple place and therefore we set up an appropriate technology center in south central Kentucky. There we had compost toilets and we started growing intensive gardens, organic ones, quite concerned about the forest itself making sure it was being taken care of well, and I got into some coal issues at the beginning but moved on into solar. We had the first complete solar house in America. We were saying that it isn't that we were just attacking what was being done wrong, but we have to look forward to a new economy that would be a renewable energy one, and so for 25 years I ran that center and I thought that was enough time, so I've come to doing more pastoral work in two of the small parishes.

CURWOOD: Why do you consider caring for the Earth to be a moral and religious issue?

Father Fritsch and Pope Francis are both members of the Society of Jesus; Pope Francis is the first Jesuit Pope. St. Ignatius of Loyola, depicted here in a painting by Peter Paul Rubens, founded the Society in 1534. (Photo: mark6mauno, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

FRITSCH: Because if we don't care for it, the vitality of the earth will be destroyed. This is the deepest of the pro-life issues, for if we don't have a living Earth, we cannot live on it ourselves, and so it's also got tremendous theological implications because we believe that Christ came to save the world, and what we have never considered is that we as part of his body are now asked to save the Earth. He is our redeemer. We enter into the very act of redemption.

CURWOOD: Why should Catholics in particular care about environmental stewardship?

FRITSCH: Well, not just Catholic but Christian people in general have been baptized in the Lord and that means that just as Christ loved the whole of creation, we are people who are like him in every way and therefore we imitate the Lord and our love for nature and for God's creation comes from the very part of our following that we commit ourselves to.

CURWOOD: Talk to me a bit about why this perspective of the Earth is important?

FRITSCH: It's very important because even though in the Acts of the Apostles, some of the very first communities brought together people who shared everything in need, the big trouble was in the last few centuries we have had Marxism, which took some of the same ideas really and imposed it with an atheist background to it, but in all actuality the world is a Commons. God created it for all of us. We have found in the course of history that more of us working together can take care of it better than individuals can, and so now when we move to a society in which an immense amount of wealth can come to a few in a very short period of time, it becomes imperative for us to bring again the idea that this is a Commons and we cannot have billionaires and destitute people at the same time. It's a poorer community because Commons means that we share together and if people can't share but instead they sequester, they take everything to themselves and hold onto it, while others don't have enough, this destroys our society.

CURWOOD: How did you feel when you heard about the Pope's encylical on the environment?

On September 24th, 2015, Pope Francis will become the first Pope to address a joint session of the U.S. Congress. (Photo: NASA HQ PHOTO, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

FRITSCH: At first, to be honest with you, I was nervous thinking that, well, he might not say enough. You know the Pope is a very busy man. How could you write a 100 page, 40,000 word document when you're doing everything that he's doing, but really when I look at his philosophy it's exactly the same as mine. I read that encyclical and I would not disagree with a single point on it. I may have arranged it a little differently because it's a very long document, longest encyclical ever written, but at the same time I think that everything that it says is good. But it also adds a burden. We've now got a duty to spread the word as much as we can. This is talking about the needs that we have on Earth and that we have a good tradition in his second chapter from our biblical tradition that we should do something about it and it's been misinterpreted, especially by those who want to make a little fortune in thinking that we could subjugate other people, you know. But the fact is that the time has come for us to share as a people in the world, not to look at ourselves as elite or different from others but that we are together with others.

CURWOOD: Tell me about your own parish's response to the Pope's encyclical.

FRITSCH: Well, they all liked the idea. In fact the person that called me a Communist and walked out one time and not only do he come back but he was one that asked that we do something about this, and my feeling is that a lot of people who are climate change deniers are really honest and good people. They don't realize what is happening, and therefore I feel like a special attention must be given with a certain amount of mercy we might say and care for those who have a difficult feeling that we have to change the status quo which they've gotten some good out of the past. If we combine a sense of mercy and pastoral care with a sense that we got to change together, I think we could do more and I think this applies not only here but I really think most of my writing is directed because, see, I'm a social conservative and I am a fiscal conservative, but on political matters I guess but I believe I call myself a true conservative because I believe it goes back beyond the capitalistic system and it has to include things which are far more sharing in our past than what we have today, and therefore if I can bring that point out to people, that they can break from their politicization, you might say the partisanization of these issues, which, when I started to work, the Republicans and Democrats were all together in 1970 to 1980, I'd like to get back to that and get away from the idea that this is a political issue. This is something far deeper than that. It is a moral issue of which we all share.

Father Fritsch earned a Ph.D. in Chemistry before embarking on the path to priesthood. (Photo: Ed Uthman, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's see here. You give me a bit of a handout describing each of the chapters of the Pope's encyclical. I gather you're sharing this with your congregation.

FRITSCH: Yes.

CURWOOD: This is quite detailed and you have at one point, 10 American applications of the encyclical. So let's just briefly describe them. The first one is to read the encyclical...

FRITSCH: ...second the need for personal and domestic conversion. And conversion is a second big point. We have to convert ourselves from what we've been thinking in order to save our Earth. We just cannot save it by some of the ways that we've had in the past. The third is to organize and attend meetings and church gatherings and, of course, that's why we're setting up one, and this is a doctrine that I'm sending out on our website. Climate change deniers hold that well, it's still a battle going on, there's still people that deny it. Well, our answer is that that is a situation they are trying to set up in order to prolong the profit motivation that is accomplishing for the big energies that is the fossil fuel ones, profits that will last just like they did in the past on the tobacco issue. Tobacco areas were really scientifically concluded back in the 60s that there was something really wrong with smoking tobacco and what happened in between almost 40 years it was always saying that there was some denial occurring. The merchants were denying it and therefore they were holding back from having regulations. We are having the same thing happening with fossil fuel. The differences is there it shortened the lives of about three million people. But here we're talking about the vitality of the Earth itself.

Father Fritsch’s work with the Center for Science in the Public Interest and Appalachia—Science in the Public Interest spanned more than thirty years. (Photo: courtesy of Father Al Fritsch)

CURWOOD: So this is the fourth point, to talk to people, those who regard themselves as climate change deniers. Now, what about your last call here?

FRITSCH: The last call is the fact that not every Catholic likes what the Pope wrote and we don't know how many there are out there, but the possibility is half of them in this country. We have far more deniers, climate change deniers in this country than they have in another parts of the world. The great possibility is many of them will do what some of our presidential candidates who are Catholic say and that is that this is beyond the Pope's expertise, but the answer is, “oh, no, this is a moral issue and that's exactly where he needs to be and must stand there”. And we have to face the fact that we have to convert and have to proselytize you might say our own people to listen to what the Pope has to say, and not just dismiss it, because it's extremely important and they've got to talk about it within their family, within their church communities and we are hoping that other parishes begin to talk among themselves in an honest way about how we all have got to change our lives in order to save our Earth.

CURWOOD: Father Albert Fritsch is the Rector of St. Elizabeth's here in Ravenna, Kentucky. Thanks so much for taking the time.

FRITSCH: Thank you.

Links

Father Albert Fritsch’s website, Earth Healing

U.S. Catholic Bishops’ letter to Congress on the encyclical

Center for Science in the Public Interest

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth