What We’re Fighting For Now Is Each Other

Air Date: Week of November 27, 2015

What We're Fighting for Now Is Each Other: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Climate Justice (Photo: Beacon Press)

Wen Stephenson was a moderate liberal and a journalist with NPR before an epiphany about global warming changed everything. Wen speaks with host Steve Curwood about his journey into the climate movement, and his new book about activists on the frontlines of the fight for climate justice.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. As we noted earlier, at the moment all roads lead to Paris for many passionate about climate protection, including writer Wen Stephenson.

STEPHENSON: I'm a father of two young children, a 15-year-old son and a now 11-year-old daughter, and when I thought about this situation and the world that they are growing up into, and what this planet may be like within their lifetime, it really lit a fire under me.

CURWOOD: But the concerns of Wen Stephenson go beyond his own children. He also sees climate disruption through the lens of the billions who didn’t create the global warming problem but who are on the front lines of suffering. A former journalist, he has turned into a climate activist, and published a book called What We’re Fighting for Now is Each Other: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Climate Justice.

STEPHENSON: There wasn't any one moment I don't think, when I realized I needed to take this leap into activism anymore than there's sort of a single moment when night turns to day. But in late 2009, we the UN negotiations in Copenhagen fail, and a lot of people felt that this was a make or break moment for the planet. And I was watching that very closely. And then in the spring of 2010, it became clear that even very weak bipartisan climate legislation in the U.S. senate was going to fail as well. And this was at a moment in my own life when I had recently left my last job, which was as the Senior Producer of NPR's On Point, and in that spring as I was looking for what to do next—I wanted to start writing again—and it was at that moment in that spring of 2010, that I had my kind of holy crap moment on climate change and realized that look we're not dealing with this. And I decided that I couldn't imagine getting up in the morning and working on anything else, especially someone in my position with my privilege, I had the ability at that moment to decide how to spend the rest of my life. I decided this is was the thing.

Wen Stephenson says that religion has played an important role in the rise of a stronger, more confrontational climate movement. (Photo: Mat McDermott, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: The preface of your book and let me quote, "This book represents no more or no less than my own search for the moral and spiritual wellsprings of that kind of courage and commitment and my search for that the very idea of climate justice."

STEPHENSON: Yeah.

CURWOOD: And in your book your search for courage and commitment on the climate movement starts with personal reflection and a meditation on Henry David Thoreau. Henry David Thoreau, of course famous for writing Walden, famous for living out there, probably little less well-known—as you point out in your book—for being really active as an abolitionist. What of Thoreau's story inspired you?

STEPHENSON: So what I realized, around this time in my life, I had started taking walks around some really beautiful conservation land around near where I live. I live in Wayland, Mass., which is west of Boston and just down the road from Walden Pond really. My house is about five or six miles south of Walden Pond, and that was one of the places that I occasionally would walk. In fact, one time I decided to get up early on a Saturday morning and walk to Walden Pond. But it really didn't have much to do with Henry David Thoreau at that point. It was just for the sake of walking, but when I had my climate freak out moment in the spring of 2010, I decided to go back to Thoreau. And the thing I realized as I went back and reread Walden, read his great essays, is that not only is Henry David Thoreau really a deeply spiritual writer—something I never really thought about before. On top of that, Henry Thoreau, who is sort of this icon of the American environmental movement, was not an “environmentalist”, you know, quote unquote. That word would've meant nothing to him, but what he was, unquestionably, was a radical abolitionist. He was a human rights activist. He was deeply involved in the underground railroad along with his mother and his sisters. He personally sheltered runaway slaves defying the fugitive slave law there in the early 1850s. At one point, he even spirited an accomplice of John Brown's Harpers Ferry raid. And this is at no small risk personally to Thoreau. This man, he was smuggling out of Concord had a price on his head. And so the way I think of it, the way I articulate this in the book is that Thoreau's very spiritual awakening in nature really led him back to society and to a very radical political engagement on behalf of his fellow human beings. And so as I like to think of it, as I put it, for Henry Thoreau to live in harmony with nature, so to speak, really is to act in solidarity with one's fellow human beings because the two can't really be separated.

Earlier this year, kayaktivists protested Shell’s oil and gas exploration in the Arctic, in an effort to keep fossil fuels in the ground. Since then, Shell has abandoned their plans. (Photo: Backbone Campaign, CC BY-2.0)

CURWOOD: Wen, tell me, what's the difference between climate justice to you now and, say, environmentalism?

STEPHENSON: Right. Right. Well, there shouldn't really be any difference, honestly. For someone like Henry Thoreau as I was just saying there really wasn't; there wouldn't be any difference. He would see them as all the same. But there are those even in the climate movement—certainly plenty of policy experts and people working on this at a political level in Washington—who don't really like to talk about justice. I mean, they don't really want to talk about race or inequality. They don't want talk about the distribution of wealth, whether at the national level or much less at the global level where Pope Francis has reminded us [that] we owe the developing world—the majority of the world's people—an enormous debt, a sort of climate debt or ecological debt. They don't really want to talk about these things because they're politically inconvenient, and I don't really want to talk about these things either because it's hard to talk about structural forms of oppression that are at the root of this crisis and that prevent us from really honestly addressing it. But, you know, if I'm serious about this, if I'm serious about justice, if I'm serious about climate, morally serious about it, then I have to face these things. And I think we do as a country.

CURWOOD: Your book is structured both with your own personal epiphany and how you've dealt with that, but then you go ahead to tell the story of climate activists and you compare them to the abolitionists, the folks who struck out in such a radical way to fight slavery. In what way do you consider climate justice activists the new abolitionists?

STEPHENSON: Right. Well, I think first it's a really important for me to say, as I try to make crystal clear in the book, that I'm not comparing climate change to slavery, which would be perverse. What I am doing is drawing inspiration from the abolitionists and from the abolitionist movement. I'm saying that our situation calls for a movement that’s every bit as radical and resolute morally and even spiritually as that movement and other radical human rights movements, you know, in our history. The narrative arc of my personal story is really that of going from a kind of self absorption, I guess, to engagement, and it's sort of about the radicalization of a privileged, white, mainstream center-left liberal, ok? And there's an analogy in that narrative to what needs to happen socially and politically here in this country, because what has happen is a kind of radicalization of the mainstream. And when I say “radical” I mean that at this hour, at this late hour, to be serious about climate is to be radical, because it's really a radical situation, you know, and it requires us to go to the root, the root of the systems that have created this. That's not going to happen until enough people really come to terms with and face up to the really radical nature of the situation. And historically—so to take it back to the abolitionists—I mean, historically this is the only way that really deep revolutionary changes have happened in this country is when ideas and principles and demands that were once considered radical and extreme: the freedom of African-Americans for example. When these became mainstream because radicals went out and forced the issue, right, whether it was on abolition or women's rights or labor rights or civil rights, gay liberation, marriage equality, all of these human rights struggles. Radicals have forced them into the mainstream consciousness and brought about a kind of moral reckoning in our society.

CURWOOD: You profile a number of people in your book who have gone through that process. Let's talk about some here. Perhaps we could begin with Tim DeChristopher.

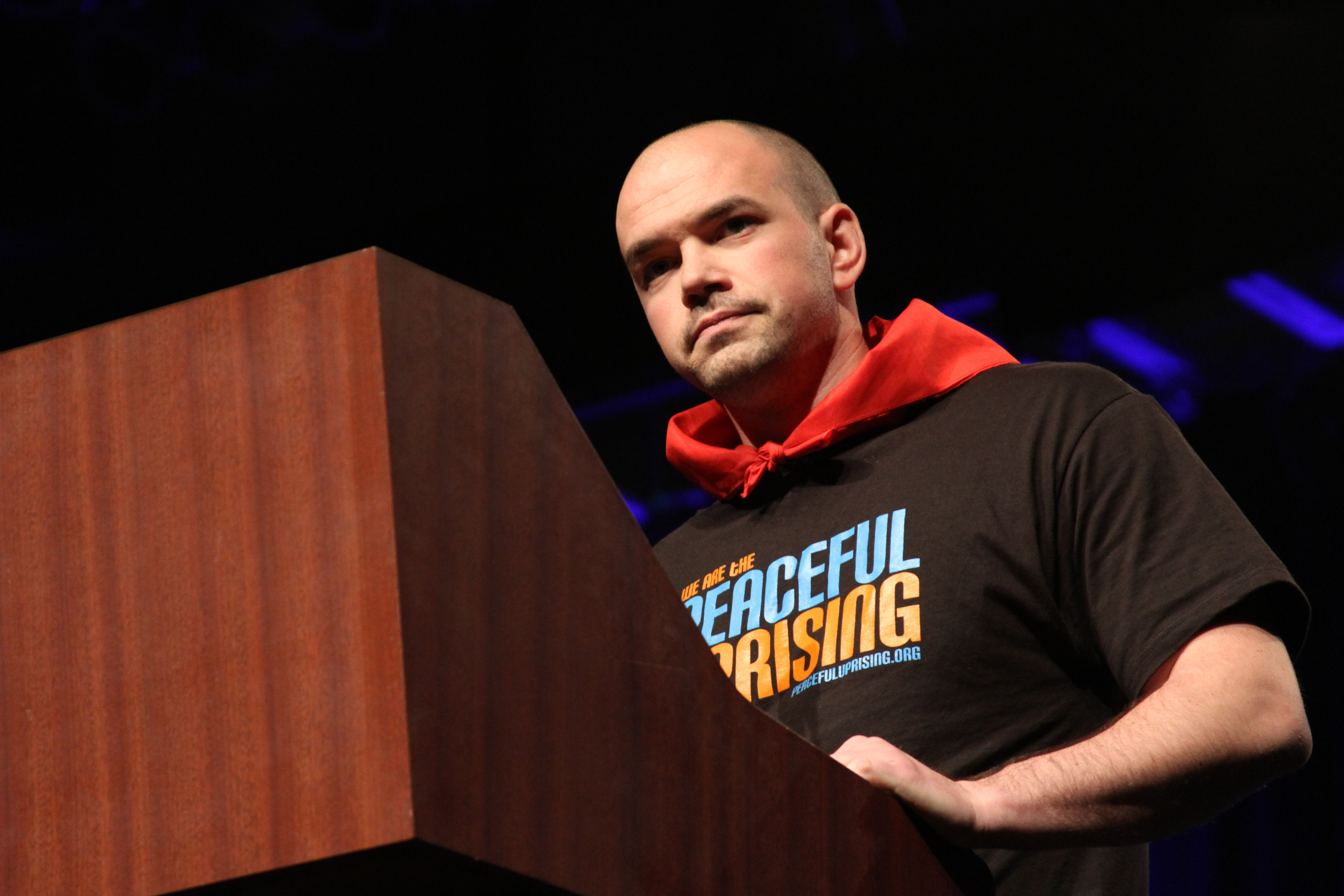

Climate activist Tim DeChristopher bid on oil and gas leases on public lands in the West in an act of civil disobedience that sent him to jail and helped galvanize the climate activism movement. (Photo: Linh Do, Flickr CC BY-2.0)

STEPHENSON: Absolutely. In 2008, Tim was an economics student at the University of Utah. He had had his own very profound kind of awakening to the climate crisis, and Tim found out about a Bureau of Land Management auction that was going to take place in Salt Lake City in which leases to drill for oil and gas on public land in southern Utah were going to be auctioned off. And so he decided to go to this auction and join a protest outside because this issue of drilling leases on public land is certainly a big environmental issue. And went down there, and he had been preparing himself for a while to take some kind of bolder, more confrontational action. And he gets down there, and there is this little protest going on outside, people walking around holding signs, and it was very tame. He decided to try to get inside the auction and they asked him as he walks up, "Sir, are you here for the auction?" He says, "Yes. Yes, I am." And then he goes over to this table and they ask him, "So are you here to be a bidder?" And he says, "Yes. Yes, I am." And they register him as bidder number 70, and he goes into the auction, and he's sitting there watching these parcels of public land being auctioned off at bargain basement prices basically given away to oil and gas companies, and he decides to take action. He starts raising his paddle, and he starts actually winning bids for parcels of land until finally he's won bids for thousands of acres worth about almost $2 million dollars that he of course has no way of paying. And so he's arrested. He goes to trial and he's ultimately sentenced to two years in federal prison for what he did. His trial became quite an event in 2011, and really helped galvanize the climate movement, the climate justice movement, and helped make the climate movement more confrontational and more open to civil disobedience and direct action. He was released in April 2013, and he came to Harvard Divinity School. He's someone else, kind of like Thoreau who was a very spiritual person, but who has been led back to a radical political engagement. And we sat down, and we've had some very long, very honest conversations about all of this and that forms a big part of the book. The last chapter of my book is largely my profile of Tim.

CURWOOD: Bill McKibben and others were really highly effective at rallying people to oppose Keystone, and I'm wondering if the climate activism movement has turned its sights on public lands. Recently there was a demonstration at the White House demanding that Obama use his powers to stop leasing public lands and onshore and offshore for the extraction of fossil fuels. What you make of that development? How important do you think it might be?

STEPHENSON: Oh, I think it's hugely important. It may very well be the next front in the climate movement. Studies show that, you know, there's enough carbon in the ground in deposits on public lands in this country to more than cancel out the benefits of President Obama's climate policies. In fact, if we were to get it all out of the ground it would certainly wreck the climate. There would be no hope of ever getting climate change under control. So, yeah I think this fight is hugely significant, and I think it's where—certainly one of the directions—the climate movement is going right now is this focus on extraction on public lands, absolutely.

CURWOOD: You're very careful not to prescribe any actions in your book. You say the leadership is spread out over many groups worldwide. What's your view of what we should do next? You call this a long haul kind of calling. How so?

STEPHENSON: Hmm. I don't think that the climate movement needs to get deeply engaged in the nitty-gritty details of the current policies that are being proposed because most of them, really all of them, don't really address the situation at the scale and urgency that's required. And it's kind of pointless to get bogged down in a sort of gridlocked partisan debate over non-solutions. So, what we need to be doing is really forcing the issue and telling the truth, however extreme it may sound, which is that we're still along way from where we need to be on this.

Wen Stephenson is an independent journalist and climate activist. (Photo: Gretjen Helene)

CURWOOD: So the negotiations around the UN Paris climate summit indicate that there will be some kind of the deal, although scientists who have reviewed the present commitments say that it would lead us to a more than six degrees Fahrenheit warming by the end of the century. How relevant do you think the UN climate process is?

STEPHENSON: So, think about what you just said: three and a half degrees Celsius. In 2012, the World Bank came out with a very influential report prepared by Germany's Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research—one of the foremost, if not the foremost climate science outfit in the world—saying that we're on track for four degrees, and that a warming of four degrees is most likely beyond our civilization's ability to adapt and so therefore quote "must be avoided", which were not doing. We're not avoiding it. I want an honest national conversation about what we're really facing: the science says we're really facing, what it would really take to address it, and what the consequences of our failure to address it are likely to be. When it comes to that conversation, when it comes to telling the truth or failing to tell the truth about climate change, there are, I like to think of it as sins of commission and sins of omission. Alright? Climate science deniers are guilty of sins of commission, right, they're telling outright lies. They're purposely misleading people ultimately for-profit, for political power. People like Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, certainly not doing that, but they're guilty of sins of omission. They're not telling the whole truth, in fact they are leaving the most important parts out. So they talk about what a serious threat climate change is, but they don't bother to mention that we've all that run out of time to address it in a meaningful way, and they don't tell us what's really necessary to address it—the actual depth and speed of the emissions cuts required. But no one in American politics is really talking about how large the gap is, the so-called ambition gap, between we know what we say is politically possible and what scientists say is physically necessary, right? And we're certainly not spelling out for the American people what the likely consequences of our failures are likely to be. So I would love to hear Hillary Clinton, for example, or Bernie Sanders for that matter, really explain to American people, really spell it out for us, just how far we are from addressing this, and how they envision the United States leading the world in closing the gap. This is an emergency situation, and we need to start acting like it, so what do they propose that we do?

CURWOOD: Wen Stephenson's new book is called, What We’re Fighting for Now is Each Other: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Climate Justice. Wen, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

STEPHENSON: You’re very welcome, Steve. Thanks.

Links

Wen’s book What We’re Fighting For Now Is Each Other

More from Wen Stephenson in The Nation

Stephenson regularly tweets on environment and climate-related issues

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth