The 2016 North American Goldman Prize Winner, a Student from Baltimore

Air Date: Week of April 22, 2016

Destiny Watford, the 20-year-old Goldman Prize-winner from Baltimore (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

Destiny Watford was still a high school student when she discovered a massive trash incinerator planned for her home town would likely be a source of choking pollution. She tells host Steve Curwood how she galvanized her fellow students and citizens to oppose this source of jobs, and about her success.

Transcript

CURWOOD: North America's winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize is quite a bit younger than Maxima, but she too earned her prize for fighting against a polluting industry in her neighborhood, in this case what would have been the nation's largest trash incinerator. Destiny Watford is now 20 years old, and studying at Towson College. Her environmental activism began as a high school student in South Baltimore, when she found out what the incinerator touted as a source of clean energy meant for her hometown.

WATFORD: Hi, my name is Destiny Watford, I’m from Curtis Bay, which is a small community in Baltimore.

CURWOOD: So, tell us a little bit about Curtis Bay. What's your community like?

WATFORD: Yeah, so Curtis Bay has...it's a small community, but it has a really long history with air pollution. So when you live in Curtis Bay, you're likely to die from lung cancer, respiratory disease and to suffer asthma. We have a lot of things that we are really proud of in our committee like parks and rec centers and community gardens. But it's divided by what seems to be an endless sea of polluting industries. We have the largest medical waste incinerator, coal terminal, the city's landfill. My mom has asthma. My neighbor died of lung cancer. I mean, in Baltimore, the deaths related to air pollution is higher than the homicide rate.

CURWOOD: Really.

Destiny’s neighborhood Curtis Bay has long had some of the worst air pollution in the country (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

WATFORD: Yeah, just to give you like an idea of how bad it is. I mean, Curtis Bay has some of the worst air pollution in the nation and has the worst air pollution in Maryland.

CURWOOD: Talk to me more about this latest threat to public health in your community. I believe it's the trash incinerator. What exactly is it and what impact do you think that this incinerator would have on public health.

WATFORD: Yeah, so there is a plan to build the nation's largest trash burning incinerator less than a mile away from my high school, Benjamin Franklin, and a group of friends and I joined together to stop it. We learned about the incinerator and we learned that it would have been burning 4,000 tons of trash every day, that is permitted to release 240 pounds of mercury every year and 1,000 pounds of lead. And from the crisis in Flint, we know about how detrimental lead can be even at tiny amounts and the damage that can cause to our health.

CURWOOD: So how did you find out about this project when you were a high school student and how did you get your friends and classmates other young folks involved in the effort to stop it?

WATFORD: So we learned about it through a local newspaper called the Baltimore Brew, and we learned that the project had been going on since 2009 when I was in middle school playing with Barbies and stuff. I didn't even know what incinerator was when I first learned about it and that was the case for a lot of people throughout Curtis Bay including our fellow students. But once we told them the facts of the incinerator and the damage that it could cause to our community, they were immediately against it. So it was really easy to get people to care about the issue because it was an act of survival and their health would be put on the line if it was built.

CURWOOD: So you put together a campaign. What role did things like art play in your campaign?

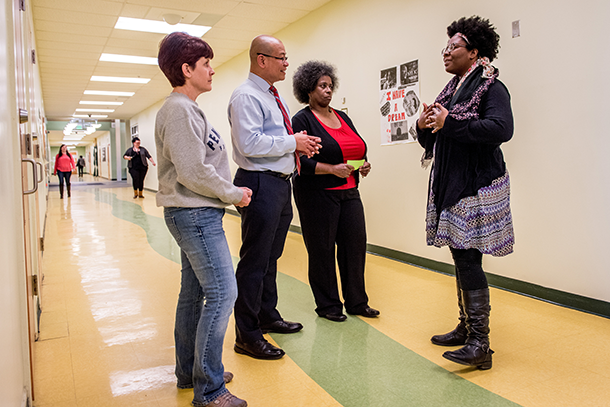

When plans were announced for a new incinerator project in Curtis Bay, Destiny organized her fellow students to help stop the project (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

WATFORD: That's a good question. I actually want to answer with a story. So while we were canvassing one day I knocked on a man's store and he answered and I told him about the incinerator and about the damage it could cause. I asked him how he felt about what he had just learned and if he was interested in learning more. And essentially what he said to me and the group was that, "You know, the work that you kids are doing is pointless. Curtis Bay is and always will be a dumping ground." And that moment kind of served as a transition for us because we recognized that it wasn't going to be enough to just tell people about the incinerator that it was going to take the shift in mentality from passive acceptance of things like the incinerator just because that's kind of the status quo to persistence which would be like saying that just because that was Curtis Bay's history doesn't mean that's has to be its future. To make that shift we relied on the tools that we had, so we weren't lobbyists pushing any political agenda. We were artists, we were poets, we were musicians, we were writers, and so we wrote poems and made music and wrote speeches and articles about what it means to live in a place like Curtis Bay in a place that's been used as a dumping ground and as a place where people's lives will be sacrificed to support the marketplace and we use those tools to shape our narrative and to tell our story in so many different ways and with so many different people that really resonated and began to make that shift and to change people's hearts and minds into thinking that there can be change and there is something that we can do. This isn't the end.

CURWOOD: I understand that you centered your campaign around getting local organizations like public schools to cut their contracts with this incinerator company. How successful has that strategy been?

WATFORD: That was huge. I mean, when we learned that public institutions like the one we knew and love like that Baltimore city public school system or like local museums like the BMA and the Walters Art Museum. We were outraged, but we also recognized that these institutions have the opportunity to make the right choice - we should be investing in not only our future as young people but also the future of our city and of our nation and investing a positive future that doesn't push our lives as risk. So, to answer your question more directly, we used arts to effectively change the hearts and minds of people on the Baltimore city school board by going to a presentation, demonstrating the art that we had created together. I recited a speech about incineration, another member of the group recited a poem that he written, a soliloquy about inspiration in Baltimore and what that means for health. And two members of the group, amazing members who are musicians and rappers, they created what we now call the "Free Your Voice Anthem”that highlighted this tradition between passive acceptance and active resistance in taking a stand.

CURWOOD: So what's the status of this incinerator now?

WATFORD: So, the MDE, which is the Maryland Department of the Environment determined that the incinerator's permits were expired and that came through a long process like months of reaching out to MDE with testimonies and petitions and letters from doctors and environmentalists stating that issues with lead and mercury. We had been sending that stuff to them for months and eventually through a lot of public pressure which included people getting arrested by doing a sit-in at MDE sacrificing their freedom to show that this is a serious issue and a matter of survival. All of that pressure led to MDE determining that Energy Answers’permits were expired which they were. So as of right now the permits that Energy Answers would need to construct, they don't have them. So, the incinerator was stopped.

CURWOOD: Destiny, what does race have to do with this?

Destiny and her fellow students convinced the school board to cut its contract with the incinerator company. 22 other organizations followed suit. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

WATFORD: That's a really good question. So, Curtis Bay is a poor neighborhood. It's a food desert and a question that we asked a lot in the group was, why here, why in Curtis Bay? Usually polluting developments like the incinerator project are concentrated in minority and low income areas in places where people have been oppressed, have been taken advantage of for generations for so long, and that there is believed to be this lack of a voice or that people will not resist if this is going to be coming to their community. It is something that we emphasize and a really important piece to mention is that originally back in 2009 when the incinerator was proposed, a community association, a small group of community members, supported the project not because it was this amazing project but because there is so little development that comes to Curtis Bay that the first thing that's offered people take up. And what we've been pushing for more recently is that we can't just accept any developments that come in. Developments that do happen in the community have to be community controlled and don't put our lives at risk.

CURWOOD: Destiny Watford is the one of the winners of this year's Goldman Environmental Prize. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WATFORD: No, thank you!

[RAP, Free Your Voice Anthem, Written and performed by Double Impact; Audrey and Leah Rozier]

[https://vimeo.com/96915571]

If the incinerator takes away a breath

How many do we need

Until there is nothing that’s left?

Until the smoke clogs up

And we can’t feel our chest

And the ones who don't catch the symptoms

Are considered blessed.

The time is now

Before our planet gets destroyed

Before death, is something we cannot avoid

It’s time for change before we don't have a choice

So let's stand tall together, and free our voice.

Chorus:

It'll all get better, we can save the world

And it starts with music, get your message heard

It'll all get better, we can save the world

You gotta free your voice, from all the boys to the girls

Links

Read more about the Goldman Prize

More about Destiny Watford on the Goldman Environmental Prize website

Read more about Destiny’s student campaign called “Free Your Voice”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth