Coral Bleaching in Kiribati

Air Date: Week of May 6, 2016

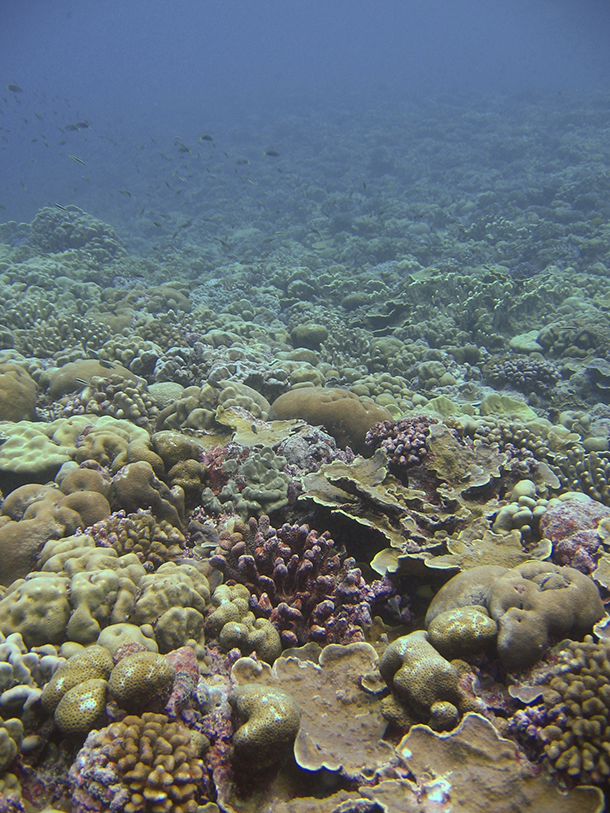

A healthy coral reef on Kiritimati, an island within the republic of Kiribati, hosts vibrant colors and active reef fish populations. (Photo: courtesy of Dr. Jessica Carilli)

Abnormally warm waters in the equatorial Pacific are devastating the coral reefs in the Pacific, including Kiribati, triggering a mass coral bleaching event and die-off on these remote islands. UMass Boston coral scientist, Jessica Carilli, and her PhD student, Sean McNally, just back from a recent research expedition in Kiribati, discuss the coral bleaching with host Steve Curwood and suggest how we can prepare coral reefs for the changing climate.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Scientists say as much as 92 percent of recent coral bleaching occurred in parts of the Pacific, thanks in part to El Niño. That led Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democratic Senator from the Ocean State, Rhode Island, to comment.

WHITEHOUSE: We’re seeing these incredibly frightening dramatic things happening things, like the die-off of the bulk of the Great Barrier Reef; these are not nothing, these are huge screams from Nature of warning.

CURWOOD: We’ll have more from Senator Whitehouse on our show next week, but now we have a first hand account of those bleached reefs are like. UMass Boston coastal geochemist Jessica Carilli studies how corals cope with climate change and pollution. She’s been diving for many years at Christmas Island, the largest coral atoll in the world, just 100 miles north of the equator and part of the Republic of Kiribati. This year, Professor Carilli sent her graduate student, Sean McNally, to check the reefs there and they’re both with us now to talk about corals and the future of our oceans.

Sean, you just came back from diving on Christmas Island. What do the coral reefs there look like?

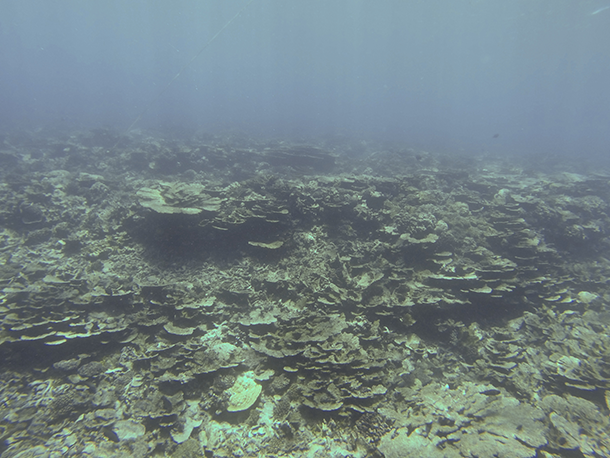

Sand and algae now cover a once-thriving coral reef community in Kiritimati, also known as Christmas Island. (Photo: courtesy of Sean McNally)

MCNALLY: It was pretty bad. Because of the recent El Niño event, we're seeing a lot of bleaching, meaning they're eventually maybe coming back or they might die. And it's pretty bleak when you go down there. You just see blues. You miss a lot of colors that corals can have underwater.

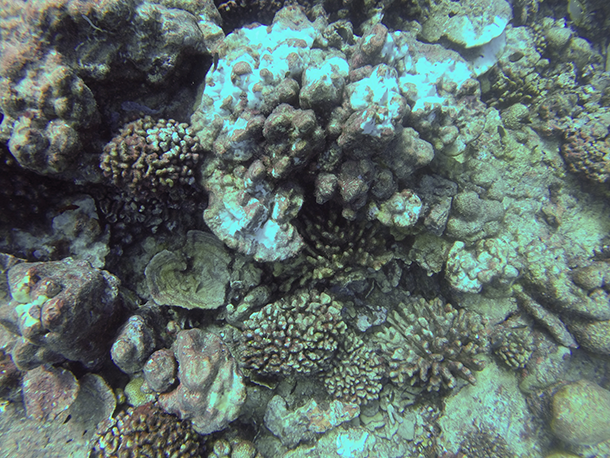

CURWOOD: What do these corals look like? I've been diving a bit and sometimes you get these brain like things and others are like fingers. These?

MCNALLY: Yeah, you explained it perfectly. So you have brain corals or mounding corals, which look like giant rocks. They're not rocks though, and then you also have fingerlike coral that branch out and they create almost like forest structures. Depending on the age of the coral, they can get pretty massive. It could be feet. We're talking a bus, the size of a bus, but they're colonial organisms so it's not just one organism. Through time they grow larger in a colony.

CURWOOD: It's a party.

MCNALLY: It's a giant party down there, literally.

CURWOOD: And it's rather colorful.

The view from an aircraft approaching Kirimati (Photo: courtesy of Sean McNally)

MCNALLY: Correct. So a healthy reef is extremely colorful, but what we're seeing on Christmas Island was that color disappeared because of the coral bleaching.

CURWOOD: What's really happening when we say that the corals are bleaching?

MCNALLY: So the corals live in an environment where they have a symbiotic relationship with Zooxanthellae which are brown algae that live in their tissues. A symbiotic relationship meaning that they get something in return from the Zooxanthellae, so they get sugars and essential nutrients to live off of, and the coral provides protection for them to live. Coral itself is an animal. It's not a plant and it just has plants that live inside of it, so when the waters get too hot the coral will expel its Zooxanthellae and it will eventually lose all of its color, and from there it'll lose its sugar source and will eventually die if they don't come back. So right now we're tracking coral resilience through this natural bleaching event in Kirabati, and we're looking at if corals that have larger lipid stores, or fat stores, will be more resilient to coral bleaching through this extreme climatic event.

CURWOOD: How do you feel when you see a bleached coral?

MCNALLY: I feel pretty bad, but I when I started coral studies about four or five years ago and I have not been lucky enough to see an extremely healthy reef in my studies.

CURWOOD: Sean, stick around. I want to talk to your professor, Jessica Carilli, for a few minutes.

MCNALLY: Sounds good.

CURWOOD: Professor, this bleaching sounds really alarming. How does the state of corals that Sean described compare to what you've seen in your visits to Kirabati in the past?

Almost 80% of the reef sites surrounding Kiritimati have died because they were not able to recover after bleaching under extreme temperatures brought about by the 2015-2016 El Nino event.(Photo: courtesy of Sean McNally)

CARILLI: Well, the last time I was on Christmas Island was in 2010, and I went to a lot of sites around the island, and they were some of the most beautiful reefs that I've seen with extremely high coral cover, very, very high diversity. The pictures that I saw from Sean's recent trip were extremely sad because most of the coral is now dead. Up to 90 percent has already died and become covered in algae, which is just devastating.

CURWOOD: Why are corals so essential?

CARILLI: Corals are basically trees. They provide habitat for thousands, millions of other creatures. They are some of the most diverse ecosystems anywhere on the planet, they provide seafood, they also buffer islands from storms. They create islands. Coral atolls are made of broken up pieces of dead corals. They're also a potential source of medicines because of their high diversity, and they take care of water quality. Places with healthy coral reefs have better water quality, less microbes in the water and this is good for human health.

CURWOOD: The coral cleans the water or the coral needs clean water?

CARILLI: A little bit of both. Corals are also are really impacted by runoff from land. That's another thing that we study in my lab. Land based runoff is not a huge problem in places like Kirabati in the middle Pacific, but in other parts of the world runoff can be a significant problem and we think that runoff, for instance from farm or from industry, can exacerbate coral bleaching.

CURWOOD: So how likely is it that these corals can recover from this bleaching?

CARILLI: Well, the corals that have completely died, they can't recover, but the reef as a whole can hopefully recover if it's repopulated by baby corals and that depends on a few things: the availability of baby corals to come to this island from elsewhere where the corals didn't die or possibly from deeper down - corals are surviving deeper - and also depends on the availability of suitable places for the baby corals to settle back on the reef. So the fact that everything has been covered in algae is a bit of a problem for that. Baby corals don't like to settle on fleshy algae, so I'm not sure. The prospects don't seem great, but I'm always trying to maintain hope.

CURWOOD: What about the corals in the Persian Gulf that seem to be able to tolerate a lot more heat than your typical coral. What's different about them and how might this be of help in the future of Kirabati?

CARILLI: So corals in different parts of the world are adapted to their local conditions. So in the Persian Gulf, waters are normally very, very warm, and so the corals there have adapted to those temperatures partly because of the coral animal itself having a different physiology and partly because they host more heat resistant algae. So, this gives us a little bit of hope. We have seen some evidence that corals after bleaching can acquire heat resistant algae, similar to the algae that the corals in the Persian Gulf host, and so this might allow corals to survive future bleaching events. There's also work going on where people are actually trying to genetically engineer more resistant corals that we could plant onto reefs to survive future warming, for example.

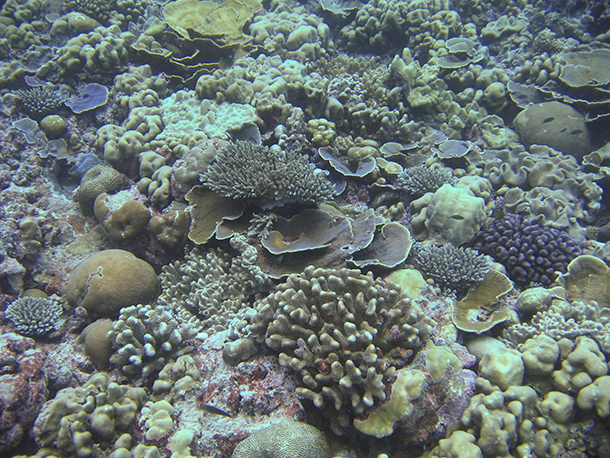

Designating marine protected areas; reducing runoff; feeding corals; and even deploying shade structures could help corals make it through bleaching events. (Photo: courtesy of Sean McNally)

CURWOOD: What if anything can be done to make corals more resilient to climate disruption?

CARILLI: There's a number of ways that people are trying to address this problem and try to help corals survive climate change. One of them is by just protecting different areas so creating something called a Marine Protected Area where, for example, people aren't allowed to fish, and they hope that that will reduce some sort of stress on a coral so that it can survive climate change. Other more local impacts that we can do is reducing run off. There's good evidence that reducing runoff will allow corals to have the upper hand to survive stressful events like bleaching.

But then there's also a lot more directed things that humans are doing. We're starting to think about actually going out and deploying shade structures during bleaching events to try to reduce the sun stress that combines with the heat stress to exacerbate bleaching, and with the work that Sean and I are doing, we're trying to answer the question that are fed corals better able to survive a bleaching event, can we just go out there and give them another food source while they are missing their symbiotic algae, if they can feed on zooplankton, can they survive?

CURWOOD: Professor, what originally drew you to corals?

CARILLI: Well, I started out studying ice cores. I've always been really interested in using natural archives to reconstruct change through time, and I've also been really interested in how humans are changing the world, and corals sort of lend themselves to these kinds of studies because we can reconstruct physical change from, for example, the chemistry of the coral skeleton and then we can also look at how those physical changes have affected the coral, for example, by looking at how their skeletal growth rates have changed through time. So corals are sort of a beautiful organism to study because they live a long time and they record change through time and allow us to look back at how things have changed in places that we didn't think to study.

Sean McNally, PhD student (left), and Dr. Jessica Carilli, coastal geochemist (right), in our studio at the University of Massachusetts Boston. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: How long do corals live?

CARILLI: They can live for hundreds of years. Individual corals and coral reefs themselves can have records that extend back many thousands of years if you look back into the fossil records.

CURWOOD: Sean, what's cool about corals?

MCNALLY: Everything. The ocean is pretty amazing. So if we were to go down in a glass bottom boat, we would see crystal clear blue water, you would see hundreds of species of fish and you'll see tons of different coral species that are branching, that are boulders, it's just forest underwater essentially and there's so many questions that you can ask and it's just endless.

CURWOOD: Sean McNally is a PhD student in marine science at UMass Boston. Jessica Carilli is an Assistant Professor of coastal geochemistry in the School for the Environmental at University of Massachusetts, Boston. Sean, Jessica, thank you both for being here.

MCNALLY: Thank you very much.

CARILLI: Thank you as well.

Links

The Carilli Lab at UMass Boston: Human Impacts on Coastal Ecosystems

New York Times: Corals around the world are threatened by bleaching

The Guardian: Bleaching in the barrier reef made likelier by Climate Change

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth