Flint, A Poster Child for Environmental Racism

Air Date: Week of August 12, 2016

People of color are especially vulnerable to environmental injustice and environmental racism. (Photo: courtesy of Petra Daher)

Dr. Robert Bullard, the “father of environmental justice”, says that the lead water disaster in Flint, Michigan is just the latest example in a long history of environmental injustice in the United States. Dr. Bullard tells host Steve Curwood that the working class and communities of color like those of Flint are far more likely to be exposed to toxic substances like lead.

Transcript

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, it’s an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Over the past two and a half years a huge environmental scandal unfolded in Flint Michigan. To save cash in a city plagued by a low tax-base, officials switched the public water source from the Detroit system to the Flint River, but the corrosive river water caused lead to leach from the pipes into the drinking water supply. As many as 12 thousand local children were exposed to high lead levels, health effects are on-going, and replacing the thousands of unsafe pipes will cost millions. Since the majority of Flint’s residents are black and low-income, some observers call this disaster a classic case of blatant environmental racism. Texas Southern University professor Robert Bullard is a noted author and expert on environmental justice.

BULLARD: The Flint water case is the latest poster child for environmental justice. You have the coming together of a perfect storm, you have a low-income community or city, over 40 percent that's below poverty, you have a majority black city. You have a city that's already under stress economically whose democratic process has been removed from the local residents, and you have a decision made by other people who don't live in Flint about their water, and water is life.

CURWOOD: What happened to Flint that residents there lost the ability, the legal ability, to govern themselves and what relation to race do you think that might have?

Robert Bullard is the Dean of the Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public Affairs at Texas Southern University in Houston, Texas. He is often described as the father of environmental justice. (Photo: Michigan School of Natural Resources & Environment, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BULLARD: Well, if you look across the state, the cities that are under state control or in receivership, most of them are majority people of color, and I think any time you have the power of duly-elected officials of a municipality stripped, and you have an overseer type government, a disaster manager so to speak, you may get decisions which may be totally different than if people who voted and lived in the city and worked in the city and were concerned about the health of residents. And I think that process of having someone to decide your own fate, that's the heart of the environmental justice movement. You know, for too many cases, from Flint, Detroit, and Cleveland, Houston, LA, you start naming the cities. Oftentimes things are placed in communities of color and low-income companies and residents didn't decide it, they didn't have their political process of voting to determine what goes in and how much comes out, and that's the justice and the equity issue that I think the Flint case is bringing to light.

CURWOOD: Now, apparently it took more than a year and a half or on the scale of a year and a half for attention to be properly paid to the the disaster, the lead poisoning disaster in Flint. Why did it take so long, do you think?

BULLARD: Well again, the Flint case fits the example of what's happening on environmental justice across-the-board. Environmental problems of pollution and environmental degradation or response to disasters and health threats, they often take longer to be acknowledged, it takes longer for the response, it takes longer for the recovery in communities of color and low-income communities, so it didn't surprise me that it took so long for this to come to light because many of these environmental justice problems and challenges that impact low-income and communities of color, they're invisible, they're invisible to the state government, invisible to the federal government, to county officials, not that community residents don't know about them and have not been complaining about them, but they are invisible when it comes to the response.

CURWOOD: This is environmental racism. What do you think motivates environmental racism in this and other cases?

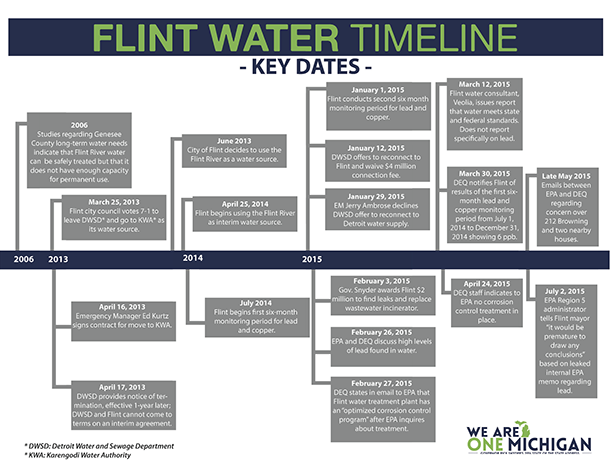

Michigan Governor Rick Snyder’s office released this Flint Water timeline to address questions on who knew what and when. According to the FlintWaterStudy, this timeline is missing some information, but overall is reasonably accurate. (Photo: Office of Michigan Governor Rick Snyder)

BULLARD: Well, I think the fact that environmental racism exists because in the real world, there are some communities that are not considered equal and valued the same as others. We have young people today talking about Black Lives Matter and I think that whole concept grows out of the fact that black communities and communities of color have not mattered for so long when it comes to giving equal protection, providing civil rights and human rights and so this whole notion of environmental racism, it's real. It's so real that even having the facts, having the documentation, having the information has never been enough to provide equal protection for people of color and poor people.

CURWOOD: Why is that?

BULLARD: Well because our society is a long way from being race neutral. Racism permeates every institution in our society. It permeates voting, it permeates housing, education, employment, so we should not be surprised that racism also permeates the way that environmental decisions are made.

CURWOOD: America has a president of recent African descent, and yet the Environmental Protection Agency, the region five that had Flint in its portfolio, dragged its feet, indeed, obstructed the work of a low-level worker who was trying to deal with the situation fitting into this pattern of environmental racism. We have a black president. Why do we still environmental racism in this country?

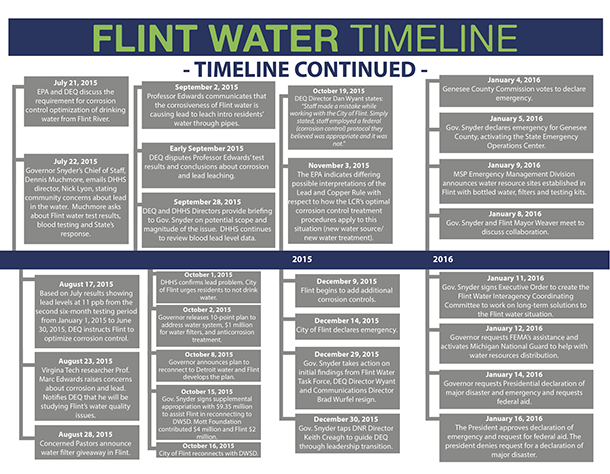

Timeline, continued. (Photo: Office of Michigan Governor Rick Snyder)

BULLARD: Well, you have to understand that the way the EPA operates is that you have the federal EPA headquartered in Washington, DC, and you have 10 regions, and the regions operate almost as autonomous little EPAs. Regional EPAs work very closely with the state departments of environmental quality and too often that relationship, that cozy relationship, gets in the way of protecting the most vulnerable communities, and so EPA regional offices will oftentimes communicate information with the state agencies and leave the impacted community out of the loop. And so even when you get complaints from Flint residents to the state officials that go up to the EPA, if that's not acted upon, you have to question whether not those individuals should be in those offices with the power and authority to control what happens in communities.

CURWOOD: Compare the national response to the natural gas leak, the massive natural gas in Porter Ranch, California, just outside of Los Angeles. Compare that response to what happened in Flint.

BULLARD: Well, I think the fact that we are talking about two different scenarios, we're talking about two examples, and so when you talk about the nature in which state officials and regional EPA officials have responded to the actions that were taken in Flint, Michigan, in a defensive way, whereas in California, I think, they have been responsive and the actions that have been taken, you don't see the kind of push back, you don't see the level of pushback. I think what this shows is that race and class still matter in terms of how the government response will be pushed forward.

I'll give you an example of ... I saw this up close and personal with how the waste that was cleaned up, the coal ash was cleaned up after the spill in Eastern Tennessee. All levels of government got behind the state of Tennessee to clean up that waste from the coal plant in eastern Tennessee in Roane county which predominantly white. But when the decision was made where to send this waste and where to dispose of it, the people in Tennessee said, “No we don't want this stuff disposed in our state or in our county”, and decision-makers at the state EPA in region four, the EPA in Atlanta decided OK, the best place to put it is to ship it 300 miles south to Perry County, Alabama, to Uniontown, a predominantly black county and predominantly black city that is very poor in Alabama, send it to the Alabama black belt. So if it's so poisoned for Eastern Tennessee, mostly white, very white, why is it not the same consideration given to a poor black area? That's the kind of blatant decision-making at the federal, state, and local level that really don't consider equity and outcomes that on their face may appear to be race neutral, but the outcome is that you're taking waste from white areas and shipping it to black areas and we say that is environmental racism.

Michigan Senators introduce bill to provide support to families in Flint. (Photo: Senate Democrats, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What about the question of climate change? To what extent is that an environmental justice issue?

BULLARD: Climate change is probably the number one environmental justice issue of our time. It is the global environmental justice issue, the communities that have contributed least to global warming and climate change will feel the impacts first, worst and longest, and I think the environmental justice movement, and the climate justice moment speak to this issue not just in terms of parts per million and CO2 and greenhouse gases, but also talk about the equity impact of climate change and talk about the solutions in that real solutions bring to the table those communities that have historically been left out of the environmental decision-making. Our communities, our front-line communities have to be in the room, have to be at the table and have to be part of any solution going forward as it relates to climate action plans.

CURWOOD: Now, you brought some students from historically black colleges and universities to Paris for the Climate Summit. What was that process like?

BULLARD: Well, because the climate change movement historically has not represented all of the diversity of our country, a group of us decided, Dr. Beverly Wright at Dillard University and myself, we decided to come together and form the Historically Black College and University Consortium on Climate Change, and we decided that we will raise the money and bring our young emerging leaders at our HBCUs to Paris for the COP 21. We were able to bring 50 students from 15 universities from Texas all the way across the Gulf Coast and South Atlantic and as far north as Pennsylvania. We bought the students and some faculty mentors who were working on climate and working on all kinds of STEM research and policy. We said that these young people, African-American students, needed to see how policies are being made and what was decided in December in Paris in 2015 will impact these young people going forward. And so they need to be in Paris to show that African-Americans are concerned about climate change and we are in solidarity with other people around the world and showing that the issues that impact people of color and people in the developing world, we have those same issues in our own country as it relates to climate justice.

CURWOOD: Bob, I think it was back in 1990 you wrote the book Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality. What's changed since then and what gives you hope for more change?

Clean water activists (Photo: Unitarian Universalist Service of California, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BULLARD: Well, when I wrote Dumping in Dixie in 1990, Dumping in Dixie was the only book, it was the environmental justice Bible at the time. Today if you Google or if you look on the Internet and search for environmental justice books there's hundreds of books on the topic. There's lots of researchers doing environmental justice scholarship. I see more and more courses and programs at college and universities integrating these concepts of justice into the curriculum across-the-board, and if you look at this whole notion of Dumping in Dixie and environmental justice we confine that book to the southern United States, but today environmental justice covers not just the United States but environmental justice now is a global movement and the issues and the framing has spread across the globe. To me, that's the maturation of our movement.

CURWOOD: Robert Bullard is the Dean of the Barbara Jordan - Mickey Leland School of Public affairs at Texas Southern University. Thanks for much for taking the time today, Bob.

BULLARD: My pleasure.

Links

About Robert Bullard and his work

Read about Environmental Injustice in Flint

It’s not just Flint: Poor communities across the country live with ‘extreme’ polluters

What Zika and the Flint Water Crisis Have in Common

Bullard: Flint is part of a pattern: 7 toxic assaults on communities of color

How the EPA Has Failed to Challenge Environmental Racism in Flint—and Beyond

A Question of Environmental Racism in Flint

More on Environmental Justice Movement and the history of Environmental Racism

Gas Leak in Los Angeles Has Residents Looking Warily Toward Flint

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth