The End of Night

Air Date: Week of August 19, 2016

Light pollution in major cities prevent many people from experiences natural darkness and a clear night sky (Photo: Tom Bricker, Creative Commons 2.0)

Humans have always had a basic fear of the dark, but the advent of electric light in the late 19th century brought control over the night in the developed world. But with an explosion of light pollution blocking out the natural night sky in much of the world, author Paul Bogard tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer we might have gone too far and it might be harming our health.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's an encore edition of Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. More than half of the world’s population now lives in cities, and the glaring lights increasingly make the sky too bright to see the stars. That’s a concern for Paul Bogard, who wrote the book “End of Night” which examines the increasing use of light for public safety, which results in light pollution blanketing our world and blotting out the heavens. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Now one of the reasons that I think people have embraced light is basically this fear of the dark. Do you think that's really what's at the base of the growth in light?

BOGARD: Well, you know it's a complex problem, a complex issue but I do think that we have a basic fear of the dark. I sometimes laugh because I admit in the book that I'm afraid of the dark and people think, you're the guy who wrote the book on the value of darkness, how can you be afraid of the dark? But I think it's a perfectly natural thing to be afraid of the dark. I think what's not natural is to then compensate for that fear by trying to light up our nights as bright as our days and to think that we can somehow do away with darkness by turning up the lights ever brighter.

Paul Bogard met many dark sky enthusiasts who seek out the earth’s darkest places (Photo: Jay Raz, Creative Commons 2.0)

PALMER: But I think there is this feeling that with light will come security. You have this feeling of the murderer or thief sort of lurking in the darkness. And so, obviously, we turn on the lights to become more safe. Has it made us in that way more safe? Or does more light make us more safe?

BOGARD: Yeah, sure, I think that's really at the heart of it, and when you ask people, do we need all this light, people say often times, well, yeah we need it for safety and security, but the truth is that while some light can help us be more safe and secure and no one's suggesting that we just turn off all the lights, but what people are suggesting is that we don't need all this light for safety and security and that in fact when you have ever more light you often create more problems than solutions. Oftentimes when you have lights they’re too bright, they cast shadows where the bad guys can hide. There's so much light in our nights that are glaring lights that make it hard for us to see, and then also, too much light tends to create the illusion of safety. We think we can be reckless purely because it's light out and that's obviously not the case.

PALMER: So it basically destroys our night vision as well.

BOGARD: Yeah it really does. One of the most startling estimates that I found what I was doing the research for the book is that some 40 percent of Americans and Western Europeans never experience or rarely experience night vision. We're in the light so much that our eyes never switch to night vision.

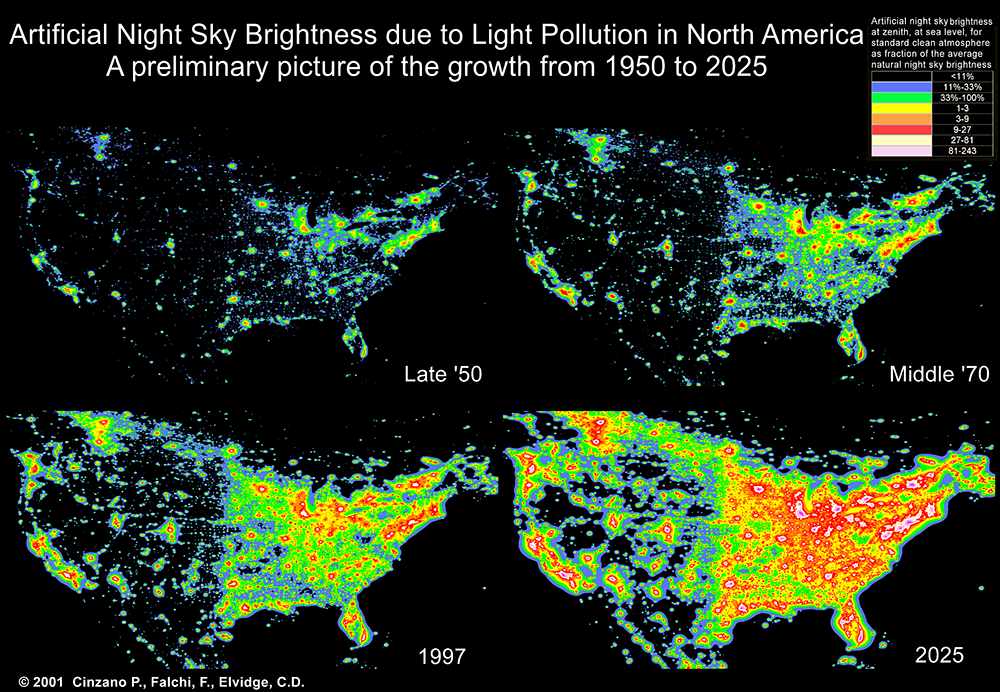

Growth in light pollution in the last 75 years (Photo: P. Cinzano, F. Falchi [University of Padova], C.D. Elvidge [NOAA National Geophysical Data Center, Boulder]. Copyright Royal Astonomical Society. Reproduced from the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astromical Society by permission of Blackwell Science)

PALMER: You tell that very sad story of somebody saying, “What are all those white dots up in the sky?”

BOGARD: [LAUGHS] Exactly and you know if you live in a major urban area, major city, you're not seeing anything close to the night sky that we ought to be able to see, and I had several nights when I was traveling for the book where, say, I was standing on a bridge in London and I looked up and I could count about 20 stars and that's just, that's nothing when it comes to the night sky.

PALMER: Well it's not only the inability to see the stars that the problem. You actually point out that this excess light is actually making us sick.

BOGARD: We're learning more and more. More and more research is showing us that light at night in fact is impacting our physical health and in three primary ways. It’s interrupting our sleep and contributing to sleep disorders, which are tied to every major disease that we're dealing with now. It's confusing our circadian rhythms, those internal rhythms that orchestrate our body's health and then perhaps most troubling it's impeding the production of the hormone melatonin. Melatonin is only produced in the dark and what scientists are finding is that a lack of melatonin in our bloodstream is linked to an increased risk for breast and prostate cancer. So nobody is saying, you know. that yeah, that light at night gives you cancer, but what everyone I talk to did say was we've evolved in bright days and dark nights just like all life on Earth and we need both for optimal health. To think that we can simply flood our nights with artificial light and have it not have an effect on our health is probably foolish.

The Bortle Scale (Photo: The International Dark Sky Association)

PALMER: One thing that I know night workers complain about is that they all put on weight. It seems to somehow in fact really upset the circadian rhythms in terms of digestion as well.

BOGARD: Yeah, it really does and I think you know the folks that are bearing the brunt of all this light probably most directly right now are those people who are working the night shift or rotating shifts and that happens to be more and more of us. And too often it's the poorer folks who need to work at night, but I talked to a number of folks who work the night shift who have put on weight and just say it's really really difficult to live this way. You feel exhausted all the time, you feel tired all the time and they can sense that it isn't right but they have to do it.

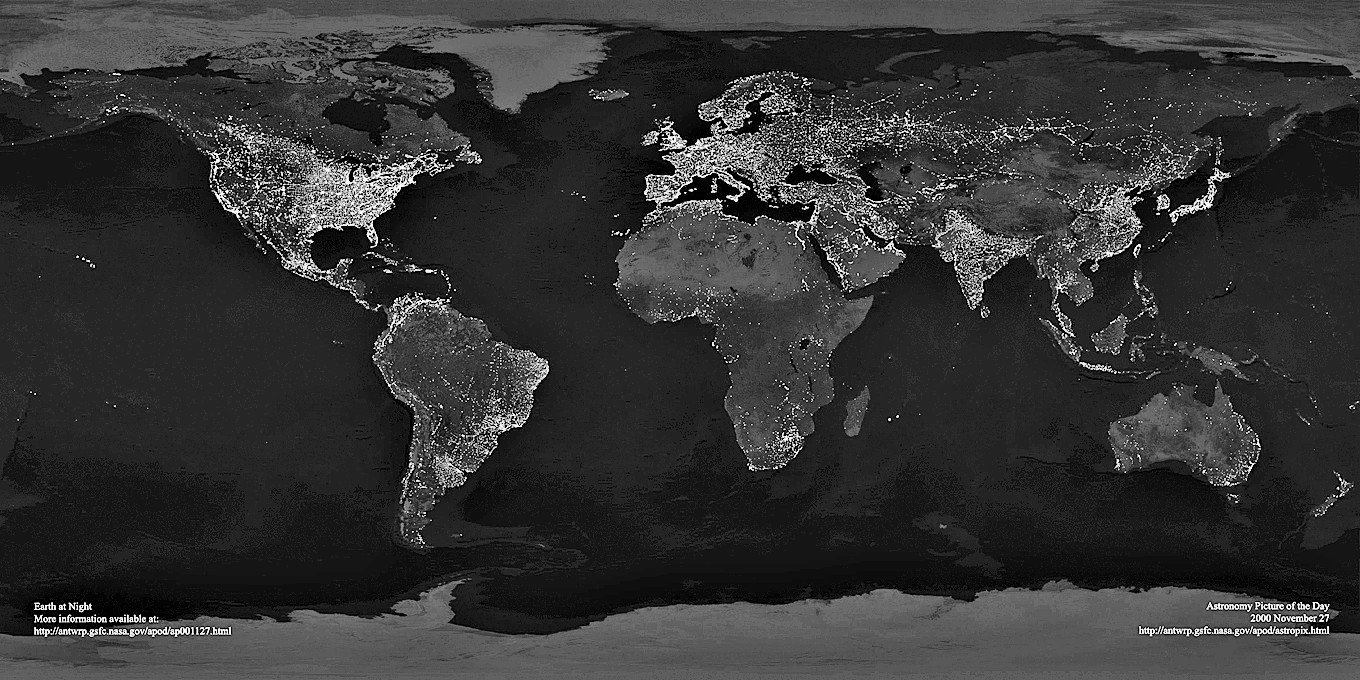

The earth at night (Photo: C. Mayhew & R. Simmon (NASA/GSFC), NOAA/NGDC, DMSP Digital Archive)

PALMER: Well even if we actually sleep in a theoretical dark room, there are all these sort of LED lights, the little lights on the alarm clocks by our bed. There are the lights on our watches, the lights on our phones. It's amazing if you just look around the bedroom—theoretically, the dark bedroom—what is still on.

BOGARD: [LAUGHS] It's true. We have a lot of little lights. And I think a lot of folks aren't even aware of how important it is to be sleeping in the dark, to pull those shades completely shut and to turn off the lights in the hall room and to, if you get up to use the bathroom in the middle of the night, to not turn that bright light on. One thing that researchers are seeing a lot of is that people are doing a lot of reading on the computer, on the tablet, their phone, what have you, right up to the time they turn off the light and go to sleep at night, and this keeps the production of melatonin from starting when it normally should. What scientists are finding is that it's the blue lights in the screen that's having the most negative effect on our physical health and a lot of the new LEDs that we're seeing in our streetlights and a lot of our gadgets are really heavy with this blue-rich white light that we really shouldn't be seeing in the night.

Excessive glare from artificial lights can actually make it more difficult to see people lurking in the night (Photo: George Fleenor)

PALMER: One of the things you're doing in your book is going around searching out these advocates for dark skies across the world. Actually there seem to be many of them. What did they advise or could we basically do to reverse this trend of ever brighter, ever brighter, ever more destructive?

BOGARD: Well you know I'm optimistic about it. I think there's a lot that we can do and it starts with the way that we use light and I like to say that light at night is not the problem, it's how we use it. So that is true in our homes where we can have light that is shining only downward, we can turn off our lights when we go to bed, that continues into our communities where we can have a lighting ordinance in our communities that will describe the kind of night that we want to have in the places that we live. Most of us don't want to live in places with glaring super-bright ugly lights. We prefer to have lighting that is subtle and nuanced and maybe even beautiful even as it provides us with the safety and security that we know we want. So, from the individual all the way up to the community and even on the statewide level there are things we can do right now to begin to control this.

Paul Bogard (Photo: James Madison University)

PALMER: Things like downward pointing street lights and stuff like that you’re talking about?

BOGARD: Absolutely. One of the biggest problems that we have with our lighting, one of the, I guess, biggest basic problems is that we have light shooting in all directions right now, and we have light that is being sent straight into the sky and we have light that's being shined into our eyes as drive down the street and we have too much light that's just shining from one neighbor or one streetlight into our houses and none of that light is doing any good. In fact, it's just all wasted light. So simply by directing our light downward just to where we need it we can have a huge positive impact.

CURWOOD: Paul Bogard wrote the book “End Of Night”. He teaches English at James Madison University in Virginia and spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer. Some conservationists are now also counting dark skies among other threatened resources and celebrating them where they still persist. Canyonlands National Park in Utah was named an International Dark Skies Park, and the Park Service is working to get a similar designation for nearby Arches National Park. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald went to see for himself.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth