The Web Imperils Endangered Species

Air Date: Week of September 29, 2017

Matilda’s Horned Viper is a newly-discovered snake species with a small natural range that leaves them vulnerable to poachers. (Photo: Tim Davenport/Wildlife Conservation Society)

The surge in data publicly available on the internet has been a boon for biological science and conservation. But it’s also being used by dishonest collectors and poachers to easily locate rare plants and animals and sell them illegally for a hefty price. Host Steve Curwood spoke with wildlife journalist Adam Welz about how the need to regulate public data and find a happy middle ground to preserve the spirit of scientific discovery while protecting at-risk species.

Transcript

CURWOOD: The Internet can help you locate everything from a popular restaurant in a strange town to the start of a remote hiking trail, but location data published online about endangered species might just put them in harm’s way. Whether it's a scientific study in an online database or a simple cell phone photo of a rare species posted on Facebook, the explosive growth of data is fueling a vast illegal trade of small plants and animals. And according to South African writer, photographer, and filmmaker Adam Welz, many people don’t seem to know or care about the problem. Mr. Welz just published an investigation with Yale E360 about this topic and joins us now from south of Cape Town. Welcome to Living on Earth, Adam!

WELZ: It's very good to be on this very interesting show.

CURWOOD: Hey, how did you become interested in the ways poachers and collectors use public data?

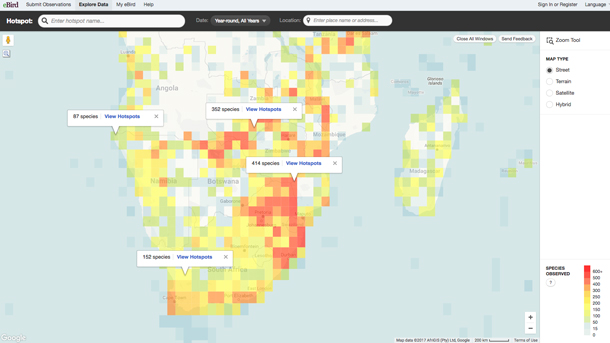

WELZ: Well, I've been interested in data for quite a long time. Even though I'm a journalist, I have a degree in ornithology and I've been interested in science, and I've also been a very keen user of various new apps that allow people to crowd source all kinds of data about wildlife, like for example, eBird, which allows ordinary bird watchers to contribute data to scientific studies by logging the birds they see when they go out bird watching. I read a few things and I heard a few things from scientists that I know, and it dawned on me that there is an enormous amount of geospatial data in the world at the moment, and it's accumulating at a rapid rate. By geospatial data I mean data about where wild species are in space and time. And I thought, man, this is really interesting because it allows us to do all this amazing science, but there's a dark side to all this data which is that poachers and people who are up to no good are increasingly using it to find their "prey" shall we say.

CURWOOD: So, what you're telling me if I were to be in the in the woods of southeast in the United States and think I had found an Ivory-billed woodpecker which has been thought to be extinct since sometime in the 1940s, I should not go and put that on eBird, huh?

WELZ: You probably should not go and put that on eBird. In general, I think if you find something that's truly special, you should give the information to somebody of great credibility, somebody perhaps who works for a well-established organization that's out in the public eye, and then keep an eye on them, too, because some of the most professional poachers and smugglers are experts in their field, are university professors. Then we also have international traders. These are people who don't necessarily know as much about the animals that they're trading as the specialists, but they move around the world picking up animals to order for their clients, again, who are these collectors who might be interested in a particular group of species, and then the third crowd in this game are the criminal syndicates, and these are the seriously organized criminals who are often dealing all kinds of other things. They're dealing illegal drugs, they're dealing guns, they're in human trafficking, and they're dealing endangered species as well because that is just another way of making money for them.

Argyroderma theartii, a succulent variety found in Knersvlakte reserve in South Africa. (Photo: Martin Heigan, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, when did this become a problem?

WELZ: There's no specific point at which this became a problem. This has progressively become more of an issue as the internet has grown, and as these databases have grown, and as people have started to more and more see the potential of sharing data either formally within the scientific community or informally among ordinary people on social media about nature. So, this is a problem that's built up over time and there are all these different streams of it, if you like. There is data, as I say, that has been acquired by scientists using interesting tracking devices. Those types of tracking technologies have become more and more sophisticated. Today, we can track, literally track tiny little honeybees with tiny little electronic tags. We can track blue whales with satellite tags.

CURWOOD: Wait a second. You can put a locator on a honeybee?

WELZ: You can in fact put a tiny locator on a honeybee. People are doing this exactly today. You can implant a tiny little transmitter in a snake, for example, that will not only tell you where the snake is, it will tell you what temperature the snake is at. It will tell you perhaps the altitude of the snake. All this kind of stuff, the technology is exploding, and like I said it's being adopted very rapidly because it gives biologists and conservationists such incredibly useful data.

CURWOOD: You know, we think about the illegal animal trade, we're thinking about the dramatic images of poached elephants or rhinos or the such, but you're telling me there's a whole network of traders and collectors who are interested in smaller species and people don't seem to be as concerned.

WELZ: Yeah, I think it's very easy to sell concern for elephants and lions and rhinos compared to concern for lizards and beetles, for example. I mean, here in South Africa we have a group of beetles we call Colophon beetles. These are very rare beetles that occur in very specific localities at very specific altitudes in very small areas. There's a huge international market for dead Colophon beetles for people to put in their collections. People pay $50, $100, even a lot more sometimes for a little beetle. People will pay a $1,000, $2,000, for certain South African lizards, for example, and it's very much more difficult if you're a campaigner to get people excited about a little beetle which might actually be far more endangered, far rarer than a White rhinoceros, for example. It's very hard to relate to this tiny little bug and it's very hard for people to comprehend how much danger some of these species are in.

CURWOOD: What's the government response like in some of the countries where traders venture in terms of how they enforce the laws regarding these species?

eBird is a community platform and online database used by nature enthusiasts to trade information on bird species. (Photo: eBird)

WELZ: I would say for smaller species almost universally law enforcement is dreadful. There's no political capital to be gained particularly by saving a lizard or some obscure plant that people have never heard of. So, when people get caught in airports with a few lizards sewn into the waistband of their pants, which happens surprisingly often, you'll find that the customs officials more often than not will just perhaps confiscate the lizards and turn a blind eye and let the guy go on the way because it simply isn't worth the paperwork for them to follow up on it. Whereas, if he was carrying a gun or some drugs or some explosives, well, that would be a completely different, different story. So, that's the difficulty that we face with these species.

CURWOOD: What is the risk of certain species getting wiped out of their natural habitats entirely because of the easy access of the public now to know where they are?

WELZ: Yeah, I think that is a real concern. Here in Southern Africa, and it's the same in some other very biodiverse countries. We have a lot of species, wild species, that only occur in very, very restricted areas. So, we'll have little succulent plants, for example, which are only found in a few acres, three or four acres, and the entire global population of this plant is in that area and there may only be a few dozen of these plants. It's extremely easy for a savvy collector to come in and wipe out an entire species in one day, and we think it may actually already have happened with a succulent plant species that we know of. A particular Japanese professor came to South Africa some years ago and seems to have taken the entire population and was later found to be selling these plants for hundreds of thousands of dollars each in Japan because, of course, he had the monopoly on the distribution of that species if you like. He quite probably had every single one, and it possibly took him less than a day to take them all.

CURWOOD: Tell me what biologists have expressed to you about where they stand on this issue of this public data that can lead to endangered critters and plants.

WELZ: Biologists are extremely divided around what to do about this geospatial data because it is extraordinarily valuable to science and to conservation. There is absolutely no dispute about it. You know, we're able to do the most incredible stuff with this data and the whole of science rests upon transparency. I mean, the entire scientific endeavor is based on the idea of transparency, is based on the idea that I can replicate the results you claim to have found in your study and your experiment. And as soon as data starts being suppressed and starts being hidden and starts being held back, it can cause damage to the core of what we're trying to do when we do biological science. So, there's a lot of scientists that are really concerned about that. On the other hand it is absolutely, blatantly obvious to everybody around that criminals are using this data, and there is also some evidence that holding the data back works.

Adam Welz is a South African wildlife journalist. (Photo: courtesy of Adam Welz)

A few years ago scientists working with the Wildlife Conservation Society in Tanzania discovered a new species of viper, a very attractive little snake, black and yellow snake, which was only found in a very small forest patch in that country. And they actually published its formal scientific description without its location, and I've just checked in with those guys and they say, “You know, there's absolutely no evidence that the poachers have actually found this species yet.”

CURWOOD: So, what can you see in terms of a middle ground then that balances the risk of public data and the benefits to scientific progress and the question of having, say, formal restrictions?

WELZ: So, I mean the thing that's interesting about this is we have no international standards for holding back or releasing this data. Certain institutions have a certain set of rules. Certain researchers have their own personal rules. Some countries even have rules, but they don't line up with other countries' rules, and I think we should have an international conference about this honestly. I think people should sit around for a good period of time, people who use the data, people who accumulate the data, data experts on wildlife crime should sit around and come up with a much more comprehensive set of, let's say, guidelines that we have at the moment.

CURWOOD: Adam Welz is a science journalist with Yale Environment 360. Thanks so much, Adam, for taking the time.

WELZ: Thanks very much.

Links

Yale E360: “Unnatural Surveillance: How Online Data Is Putting Species at Risk”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth