Tamed and Untamed: Close Encounters of the Animal Kind

Air Date: Week of October 6, 2017

The octopus is sometimes depicted as a monster -- Victor Hugo described these deep-sea creatures as horrifying – but writers Sy Montgomery and Liz Thomas say octopuses are far more personable than we realize. (Photo: Scott Ableman, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

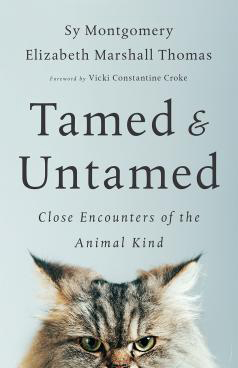

The science of animal psychology is still developing and what exactly your family dogs, or wild rabbits are thinking is a fascinating topic for many, including committed animal observers, Sy Montgomery and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas. These best-selling writers believe these and all creatures, wild or domesticated, deserve respect. Their new collaborative book of essays, Tamed and Untamed, dives into the curious mental and emotional space among creatures and humans, as they explained to host Steve Curwood, when he visited Sy Montgomery’s New Hampshire farmhouse.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[DOOR CREAKS OPEN, DOG BARKS]

On a warm afternoon in late summer Thurber, the Border Collie, welcomes me into his home. He shares an old New Hampshire farmhouse with writer Sy Montgomery, and today they are joined by author Elizabeth Marshall Thomas.

Sy is an old friend of Living on Earth who over the years has celebrated pigs, octopuses, sharks, pink dolphins, moon bears, and more with stories from around the globe. Elizabeth Marshall Thomas is noted for writing The Hidden Life of Dogs, a groundbreaking book probing dog psychology.

Sy heads outside into her garden.

MONTGOMERY: I will lead the way...

[SOUNDS OF WIND, BIRDS, OUTSIDE THE HOUSE]

CURWOOD: These best-selling authors have teamed up on Tamed and Untamed: Close Encounters of the Animal Kind, a book of essays that explores how wild and domesticated creatures and people relate. The essays are adapted from a Boston Globe column they co-wrote that sometimes offered advice that, as Sy admits, raised some eyebrows.

MONTGOMERY: We kind of got in trouble for our first Q and A.

CURWOOD: Uh-oh.

MONTGOMERY: Someone wrote in and they said you know I've got this dog who barks, and I love him so much, and now I have this new boyfriend, and he doesn't want me to keep the dog, which I do. And we said, you know, we normally don't recommend euthanasia, but your boyfriend has got to go.

CURWOOD: So, you wrote this book with, with Sy Montgomery, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas but both my producer, Noble, and I, when we were reading the book had a lot of trouble figuring out whose voice was whose. For each story in it, you had the same voice. How did that come about?

THOMAS: Maybe we just had the same voice before we ever met. I bet that's it.

The Stunt Dog Experience is a travelling circus show that takes in abandoned dogs and trains them to perform for a crowd. According to Sy Montgomery, dogs want tasks to occupy their time and enthusiastically take on jobs. (Photo: Branson Convention and Visitors’ Bureau, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: We did think about that, and that's why with each chapter at the top we reveal which one of us is speaking, but I think Liz has been a very big influence on my writing. I think we come from the same heart. I mean, what we're saying in this book and every single essay, whether it's about hyraxes - these little groundhog-sized relatives of elephants who live in Africa - or an octopus at the New England Aquarium or the dog at your feet, these lives are so fascinating, so intricate, so mysterious, so thrilling, and so worthy of our respect and affection and awe. That's what we're saying in every single essay, and that may be why that kind of heart comes through.

CURWOOD: There's a theme throughout your book. It's a finger-wagging theme about people who abandon their animals, who abandon their pets.

THOMAS: Yeah, I have two cats who my neighbor found as kittens by the side of a long empty road. Somebody just tossed them out of a car. And she couldn't take them, but I could. She called me and I, of course, came and got them. [LAUGHS] And they're with me now. They're wonderful cats. They were Russian Blues, and if you buy one it's expensive so the person didn't even know that she could have sold them for hundreds of dollars. I mean, but that's not the point. The point is that, how can you do that? How can you do a thing like that?

Another woman released a rabbit in my field, and the rabbit had never been alone before, and he'd never been out in the wild before, so to speak. He had no idea what to do. And also it was in the middle of the field so he could be seen from every direction. He wasn't happy about that, and he saw our house in the distance, and he came to it and he went into the garage.

The woman, I'm sure she was letting him free. She thought that animals are on automatic pilot. When they get in the woods, they’ll know exactly what to do, and he'd be happy, and so it wasn't an evil thing on her part. But it didn't work. The dogs found him before I did, and they killed him. And I think people don't think along those lines.

Rats get a bad rap, says Sy Montgomery, but they’re much more like humans than we think. One of our shared characteristics is laughter. (Photo: zemasterdod, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

We're alike in every other way with every other mammal. OK? We have hearts, we have livers, we have kidneys. But the brains aren't the same? Of course they're the same. Why wouldn't an animal feel the same way we do? Of course, they do.

MONTGOMERY: And the idea that animals don't think is insane. I mean they don't think about their shopping lists. They don't think about what they're going to wear tomorrow, but they think. And anthropomorphism is one of those bugabears that we take on also in the book and in our columns and in our other work. The idea that, when you talk about an animal having thoughts and feelings, that this is anthropomorphic, well, that's ridiculous. Of course they have thoughts and feelings. A much worse mistake is to think that they don't have thoughts and feelings.

It's easy to make a mistake and even with a human being attribute your own thoughts and feelings to them. All of us have bought a birthday present for someone that didn't go over. All of us have asked someone out on a date that didn't want to go. And that happens with animals too. One of the essays is about this, in fact, that people can make mistakes like the veterinarian who thought that the Tasmanian Devil was so calm, it was yawning. Well, then it bit her. It was a gape threat, it wasn't a yawn. But you know you can make that mistake, but a much bigger mistake is to think that they don't have thoughts and feelings.

THOMAS: There's a new word in the English language, and it was invented by...He's a famous scientist. He's a biologist and primatologist, Frans de Waal. He invented the word “anthropodenial” which is the opposite of anthropomorphism, and it means presenting an animal as if it did not have human characteristics.

CURWOOD: Now, I think Sy wrote this essay, about going to see a sort of a dog circus.

MONTGOMERY: Oh, yes, we went together. Liz wrote that, but I took her.

THOMAS: Oh, yeah.

MONTGOMERY: That was...what was it? It was some kind of celebration. It was so much fun.

THOMAS: It was fabulous, and what we saw! All the dogs in the show, they did things you've never seen a dog or a person or anything do before.

CURWOOD: Like?

THOMAS: Well, one dog jumped up, a little dog, jumped up on his owner/trainer's hand and stood on her front legs on his hand with her hind legs in the air, and he lifted it up like that, and she - I reached my arm way up in the sky -- He lifted his arm way up and she retained the pose and came down. I mean a person couldn't do that. I mean a person can't do a lot of things. That's no comparison. But they would be trembling with excitement, and then they'd be called to do something, and they would rush off and do it, and they loved it.

Like this chicken, Sy Montgomery’s flock of hens roams freely during the day. Though these clucking birds are often considered unintelligent, the writer argues that they are quite smart, and can even develop distinct names for the people and animals around them. (Photo: Grey World, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

All of these dogs were strays or abandoned or from shelters or they found on the street wandering homeless, dogs that somebody else thought was worthless and tossed them, and these dogs were phenomenal what they were able to do. So, this is what people toss when they get rid of their pets.

MONTGOMERY: Some people think like, “Oh, you know, training a dog is just forcing it to do some horrible thing that…” No, they love having something to do, as do a lot of animals. They'd rather have something to do than nothing to do.

THOMAS: And people are the same, so there we are.

MONTGOMERY: And they love our company, and in fact, Thurber, our dog, is taking - I kind of hate to admit this because I purposely did not have children - but he's taking dance lessons right now.

THOMAS: [LAUGHS] My dogs are learning not to pee in the house.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Now, so you're teaching your dog to dance. Sy, in this book there's another dance scene with...

MONTGOMERY: Snowball, the Dancing Cockatoo!

CURWOOD: So, describe this for me.

MONTGOMERY: Well, I actually found out about Snowball the Dancing Cockatoo on YouTube. He was an unwanted bird. He was dropped off at this parrot rescue facility in Indiana, and he came with a CD. And when he was dropped off, the fellow told Irena Schulz, you should play that and see what happens. Well, she had a lot of birds to take care of, so she didn't get a chance to do it right away, but when she did, she put it on. It was by the Backstreet Boys, it was one of their really great rockin’ songs.

[BACK STREET BOYS MUSIC. SOUNDS OF COCKATOO CALLING. Backstreet Boys, “Everybody” on Backstreet’s Back, by Denniz PoP/Max Martin, Jive – Transcontinental Records]

MONTGOMERY: Well, the Cockatoo starts rockin’ out. His crest is rising. His wings are spreading. His tail feathers spreading. His feet are going up and down, and he's doing it to the beat of the music. He's also calling out.

[MUSIC: Backstreet Boys, “Everybody” on Backstreet’s Back, by Denniz PoP/Max Martin, Jive – Transcontinental Records]

MONTGOMERY: She makes a video of this, puts it on YouTube. It went viral. Well, turns out, this was the beginning of an important discovery about abilities that parrots have.

[MUSIC STOPS]

MONTGOMERY: They have an ability that was previously thought to belong only to so-called higher minds like ours, and that is called “beat perception and synchronization.” They can anticipate the next beat, even though, for you and me, we unconsciously tap our feet to the beat, but other animals apparently can't do this, but parrots can, and it's probably associated with vocal learning.

So, I, of course, had to see this. I had to write about it, and I spent one of my birthdays with Snowball rocking out to the tunes of my choice.

[MUSIC: Backstreet Boys, “Everybody” on Backstreet’s Back, by Denniz PoP/Max Martin, Jive – Transcontinental Records]

Sy Montgomery and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas co-wrote Tamed and Untamed, a collection of essays adapted from their Boston Globe column by the same name. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

MONTGOMERY: A researcher named Ani Patel did a project on this. He had written a wonderful book on music and the brain, and he also saw this YouTube video and worked with Irena Schulz to produce, actually several papers now. He found that lots of parrots can do this, and some other birds can do it, and it only works with certain tempi.

CURWOOD: You know, correct me if I'm wrong, but I think at some point in your book you say that rats like music.

MONTGOMERY: Yes, rats do like music.

CURWOOD: What kind of music?

MONTGOMERY: Well, you know I don't think this has been as systematically tested, but rats are very like us in many ways. Rats laugh. If you record it and then speed it up or slow it down, you can hear them laughing, and they laugh when they're tickled, just like we do. And these are animals that everybody thinks of as vermin, and yet they are so like us. They enjoy the same kind of stuff that we do.

THOMAS: Well, we use rats, we use mice for experiments that we think will help our bodies, so we may think we're nothing like them, but of course we really are, biologically speaking, just physically speaking.

MONTGOMERY: And we can sometimes get to animals’ thoughts, and rats are one of the species that we can sometimes almost literally see their thoughts. When they run a maze, you can see what their brainwaves are doing as they come to different parts of the maze. And recently there was an experiment looking at what their brainwaves looked like when rats were dreaming. And they could see the brainwaves were exactly the same as when the rats were running the maze. The rats were dreaming about their work, just like we dream about our days and our work.

CURWOOD: In the book, there was, well, kind of this theme of animals with bad reputations among certain humans. How conscious was that decision, do you think?

MONTGOMERY: I think we, we really did want to rehabilitate some of these reputations for animals because, if you remove a bad reputation, you can begin to appreciate the creature for what it is. Rats are one example. Great white sharks. Octopuses even. Octopuses were thought of as these horrible monsters that Victor Hugo certainly didn't do them any good in the PR department, but they're not at all. It's just preconceived notions, and it's fun to knock those down and instead welcome people into the company of these great animals and appreciate them for what they really are.

THOMAS: Yeah, and there are ways of looking at it. I was thinking of, I think, it's in one of the essays. If you see a fly or something like that, you swat it.

CURWOOD: Even as Elizabeth Marshall Thomas makes her point, it’s clear that any stray insect or tick in Sy Montgomery’s expansive yard is likely to be gobbled up by an ever-present flock.

THOMAS: If an eagle, a magnificent eagle, was the size of a fly, you would swat it.

[SOUNDS OF CHICKENS]

CURWOOD: Now, these ladies they’re are two-legged, and they have these red combs. They're chickens. They're coming towards us. Someplace in this book you say that chickens actually name people, or they seem to.

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, this was not my discovery. This was my friend and colleague Melissa Cowie’s discovery. She's the author of a kid's guide to keeping chickens, which is how I met her.

Sy Montgomery (left) and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas (right) pose with Montgomery’s beloved border collie, Thurber. They spoke with Steve Curwood at Montgomery’s New Hampshire farmhouse. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Well, she was out with her hens one morning, just throwing scratch, and noticed that one of her chickens, a six-year-old named Oyster was using a different voice than usual, and she knows what her chickens are saying. She's decoded quite a number of different vocalizations, like, “Oh I've just laid an egg”, or “Hi, how are you?”, or “Oh my God, there's a hawk over there!” They have lots of different things that we know what they say. But there was this one vocalization that she'd never heard before, and soon everyone in the coop was using it, and they just used it when Melissa walked into the coop. Well, we figured out that that was the name the chickens had devised for her.

And this happens with a lot of animals. They have specific names for specific events, specific predators, or maybe even specific people, and the fact that a regular person, just paying attention to the chickens in her backyard, made this huge discovery about the intelligence of an animal that so many of us think of as ordinary, just shows us how splendid and exciting this world is, no matter what animal or plant or landscape you set your eyes on. There's just so much out there to be revealed.

In a book like this what you're trying to get across is, “Isn't this Earth splendid? Aren't these animals wonderful? And don't we owe them our affection and respect?”

And, even though this is just a book of essays that we loved writing, it's part of a growing assemblage of writing from people who are really, I think, believing that we can build a more compassionate world. You alter your behavior, once you realize that this chicken loves her life. She doesn't particularly want to have her head chopped off and her flesh eaten, and, you know, the ocean which is full of octopuses and sharks and fish, we can't be dumping pollutants and garbage and plastics into it, if these individual lives are going to suffer. We can't continue to alter the climate of our world if we realize it's full of lives just as wondrous as our own.

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas are co-authors of Tamed and Untamed: Close Encounters of the Animal Kind. Thank you both for spending this time with us.

THOMAS: Oh, thank you so much for having us.

MONTGOMERY: We're so glad that you came.

Links

Chelsea Green Publishing webpage on Tamed and Untamed

More about author Sy Montgomery

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth