Three Mile Island Retrospective

Air Date: Week of March 26, 1999

Three Mile Island was the site of America's worst commercial nuclear accident. The nuclear core suffered a partial meltdown, and radiation releases forced the evacuation of thousands of people.

Twenty years after Three Mile Island we look back at the nation's worst commercial nuclear accident. Using archival materials and interviews with area residents who lived through the accident, Living On Earth’s Terry FitzPatrick reconstructs the days in late March and early April, 1979, that changed the nation's energy policy. He also looks at whether radiation released during the accident has had lasting health effects on people who live near the plant.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Along the banks of the Susquehanna River here near Middletown, Pennsylvania, you can see the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. It's by far the dominant feature on the landscape.

(Humming)

CURWOOD: There's a gigantic hum of electric power that emanates from this sprawling facility. It's out on a sand bar in the middle of the river and has 4 concrete cooling towers, each one as tall as a 40-story building. Dense clouds of white water vapor are billowing up from 2 of the towers. It's dramatic, but it's normal. But what happened here on March 28, 1979, was anything but normal. Three Mile Island was the site of America's worst commercial nuclear accident. The nuclear core suffered a partial meltdown, and radiation releases forced the evacuation of thousands of people. Today, 20 years after the accident, we'll try to assess its impact on the physical and emotional health of people who live here. And we'll explore how this single event changed the course of the nuclear industry and the nation's energy policy. In a few minutes, we'll talk with a spokesman for the plant, and with a woman whose family used to farm the land where the facility now sits. But first, Living on Earth's Terry FitzPatrick takes us back to the spring of 1979.

The Three Mile Island Nuclear Power Plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania was the site of America's worst commercial nuclear accident. On March 28, 1979, a combination of technical malfunctions and human error caused the reactor core of Unit Two to melt, releasing radioactivity and forcing the evacuation of thousands of local residents. Unit Two remains closed, but Unit One continues to generate power. Clouds of water vapor rise from Unit One's massive cooling towers along the banks of the Susquehanna River.

(Photo: Terry FitzPatrick)

(Humming continues up and under)

FITZ PATRICK: It happened on a Wednesday morning at 4AM, at one of America's newest and biggest nuclear power plants.

(Voice: "This breaking story has just come in. State police in Harrisburg have been called to the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, where plant officials have called a general emergency...)

FITZ PATRICK: A leaky pipe and faulty valve forced an emergency shutdown.

WHITTICK: I heard this loud roar. It sounded like a big jet taking off very close by.

FITZ PATRICK: The noise awakened William Whittick, who lives a mile away from the plant.

WHITTICK: I went to the window, and I could see this jet of steam coming up.

(Humming continues; fade to distant radio voices)

FITZ PATRICK: Inside the control room, inadequate instruments and poorly- trained operators led officials to believe the radioactive core was safely covered with coolant. In fact, the reactor was melting.

(Radio voices continue)

MAN 1: That all the numbers you got?

MAN 2: Yeah, those are the only numbers.

MAN 1: Okay.

FITZ PATRICK: When consultants from the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission arrived later that day, they were shocked by what they found.

MAN 1: Couple of radiation levels.

MAN 2: Okay.

MAN 1: Two hundred R per hour.

MAN 2: Yeah.

MAN 1: In-stack containment --

MAN 2: Holy Jesus! Oh, they've got a release inside. Two hundred R per hour?

FITZ PATRICK: Several hours passed before plant officials told local authorities about the shutdown. At first, they said the situation was under control. Then they said the reactor was still unstable, and that radiation was released into the surrounding community. Robert Reed, who was mayor of Middletown, the town closest to the plant, was furious he hadn't been told the full story immediately.

REED: Here it is, 8, 8:30 in the morning. People are going to work, kids are going to school, out in the playground. I said boy oh boy, I think we got zapped by a good dose of radiation. And I felt, here we have a nuclear facility run by people that don't know what they're doing. Either they don't know what they're doing or they're telling us lies.

ANNOUNCER: This is the CBS Evening News, with Walter Cronkite.

CRONKITE: Good evening. The world has never known a day quite like today. It faced the considerable uncertainties and dangers of the worst nuclear power plant accident of the atomic age. And the horror tonight is that it could get much worse. It has not...

FITZ PATRICK: Over the next few days, things did get worse. Radioactive gas continued to escape, as technicians struggled to cool the smouldering core and prevent a rupture in the building that contained it. Pennsylvania Governor Dick Thornburg called for a limited evacuation.

THORNBURG: I am advising those who may be particularly susceptible to the effects of any radiation, that is, pregnant women and preschool-age children, to leave the area within a 5-mile radius of the Three Mile Island facility until further notice.

FITZ PATRICK: To reassure the public that the situation was under control, President Jimmy Carter, a nuclear engineer himself, toured the facility with the First Lady at his side.

CARTER: The primary and overriding concern for all of us is the health and the safety of the people of this entire area. If we make an error, all of us want to err on the side of extra precautions and extra safety.

(Humming continues)

FITZ PATRICK: Five days after the accident began, technicians restabilized the reactor, and the 140,000 people who had evacuated returned home. Eventually they would learn that 50% of the reactor core had melted, sending 20 tons of uranium fuel onto the containment room floor.

(A motor starts up. A dog barks.)

FITZ PATRICK: Now, 2 decades later, some area residents are still bitter over the way the accident was handled. And people still debate whether radiation releases harmed the public. Plant officials say the average radiation exposure to people living within 10 miles of Three Mile Island was equivalent to a chest X-ray. Dr. Kenneth Miller of Penn State University Hospital in nearby Hershey, Pennsylvania, says there have been no long-term health effects.

MILLER: About a dozen different health effects studies conducted on the populations in this area showed that there have been no increases in any type of disease in this area that could be attributed to anything that happened during that accident.

FITZ PATRICK: However, researchers from the University of North Carolina have recently found an alarming incidence of cancer near the plant. Their conclusion is hotly debated among scientists, and the conflicting medical studies have left residents like Mary Osborn suspicious and angry.

OSBORN: The industry and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and our state government and Federal government got away with murder here. You know, that's the simple truth.

FITZ PATRICK: Ms. Osborn believes the amount of radiation emitted during the accident was far greater than officials have disclosed. And since 1979, she's documented subsequent radiation releases during clean-up operations at the plant. The damaged reactor is closed forever, but Ms. Osborn still keeps a black hand-held device on her coffee table.

Mary Osborn of the grassroots anti-nuclear group TMI Alert, checks her personal radiation monitor. Many people who live near the plant now keep "Rad Alert" devices inside their homes. The device creates a high-pitched chirping sound, much like a household smoke alarm, if excessive radiation is detected. (Photo: Terry FitzPatrick)

OSBORN: This is my radiation monitor. (Beeps) I have mine on all the time.

FITZ PATRICK: So that goes off every now and then around here.

OSBORN: Yes, it does. Yeah. A lot of the time it's just background.

FITZ PATRICK: This seems depressing. Because you've got to live with this thing?

OSBORN: (laughs) Yeah, but you have to understand something. Living without it is more depressing, you know, because after you go through an accident and you're lied to so much, who do you trust? (Beeps)

FITZ PATRICK: This is life today in the shadow of Three Mile Island. Some residents live in fear. And whenever a neighbor or family member becomes seriously ill, they question if the accident somehow caused it. But not everyone feels this way.

(Traffic)

LANE: I've had a health effect. I certainly don't blame it on this incident.

FITZ PATRICK: Current Middletown Mayor, Barbara Lane.

LANE: I developed non-Hodgekins lymphoma, and never one time did I question myself, was it was out of TMI? Because the type of non-Hodgekins I had probably was attributed to chemicals through hair dye, and never one time did I blame it on the accident.

FITZ PATRICK: Others, though, remain convinced the accident has taken a terrible toll. Annie Myers lived on a dairy farm 5 miles from the plant, but did not evacuate.

MYERS: Well, that day, I always remember because it was my birthday. It was frightening. I thought it was frightening.

FITZ PATRICK: Ms. Myers picks up a portrait of her family. Her husband, Herbert, is pictured on the left.

(To Myers) This is him here.

MYERS: Mm hm. He had thyroid cancer, died October, it was 9 years.

FITZ PATRICK: Nine years ago.

MYERS: Mm hm.

FITZ PATRICK: There's no proof the accident at Three Mile Island killed Herbert Myers. But his widow is convinced it did.

MYERS: I still believe, yeah, that it had something to do with it, because 3 years after my husband died my son got cancer, too.

FITZ PATRICK: Her son's thyroid cancer is currently in remission.

(Shifting)

FITZ PATRICK: Ms. Myers gets up from the couch where we've been sitting and takes me to her bedroom.

(A door opens)

FITZ PATRICK: From the closet, she pulls out what is perhaps the strangest piece of evidence suggesting her farm was hit by radiation.

Local resident Annie Meyers holds a two-headed calf that was stillborn on her family farm near the Three Mile Island Plant two years after the accident. The family preserved the heads to show to curious neighbors. Ms. Meyers' husband died of thyroid cancer several years after this calf was born. Her son also developed thyroid cancer, which is currently in remission. The family did not evacuate during the accident, remaining to care for their herd of dairy cows. Ms. Meyers is uncertain if the accident caused the genetic mutation in this calf, or the cancers in her family.(Photo: Terry FitzPatrick)

(To Myers) Oh my God.

(The door shuts)

MYERS: This is the 2-headed calf.

FITZ PATRICK: Oh.

A stillborn calf with 2 heads, born 2 years after the accident. The family had a taxidermist preserve it.

(To Myers) It's almost like Siamese twin heads.

MYERS: Mm hm. Yeah, they both have eyes. They both have a nose, but only, like, 2 ears.

FITZ PATRICK: Joined at the back of the head.

MYERS: Right.

FITZ PATRICK: There's no proof that radiation from Three Mile Island caused this bizarre mutation. In fact, quite a few 2-headed calves have been born elsewhere in the US. Still, the image of this animal haunts this region, underscoring the lingering fear about what happened here 20 years ago.

(Traffic and bird song, horns)

FITZ PATRICK: Today, Middletown, Pennsylvania, looks like any other American town. Officials had feared a devastating exodus and a crash in housing prices. That did not occur. In fact, clean-up work at the plant created high-paying jobs.

(Humming continues)

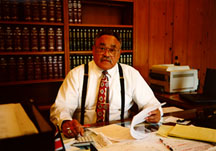

Former Middletown, Pennsylvania Mayor Robert Reid, who helped evacuate pregnant women and pre-school-age children after radiation releases from the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. Today, citing what he feels is a rash of cancer in his town, Mr. Reid feels that all residents should have been evacuated. (Photo: Terry Fitzpatrick)

FITZ PATRICK: Many people also feared the restart of Three Mile Island's other nuclear reactor, which had been idled for refueling when disaster struck its twin. But it's been running without incident since 1985, and even former Middletown mayor Robert Reed feels it's safe.

REED: There's one thing we have going for us. We know how to run a plant now. There are plants all over this country. They never had an accident. There's one out there waiting to happen. But I don't think it'll be at this plant again.

(Traffic)

FITZ PATRICK: For Living on Earth, I'm Terry FitzPatrick in Middletown, Pennsylvania.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth