January 2, 2004

Air Date: January 2, 2004

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Fast Food O’Natural

/ Bruce GellermanView the page for this story

Bruce Gellerman reports on a number of entrepreneurs who are out to quench America’s thirst and palate for healthy food served up fast. “Healthy Fast Food” can be organic or just good for you, and it may just change the entire fast food business. (09:00)

Commodified Oxygen

/ Miriam LandmanView the page for this story

Commentator Miriam Landman tells us about her first visit to a new bar in San Francisco – one that serves up oxygen instead of alcohol. (03:15)

Almanac/Spindletop

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about Spindletop. This gusher in 1901 ushered in the oil era in Texas. (01:30)

The Sounds of Nature

/ Guy HandView the page for this story

Join us for a visit to a nature sound recording workshop in the Sierra mountains of California. Photographer and producer Guy Hand tells us about learning to make the transition from sight to sound. (10:30)

()

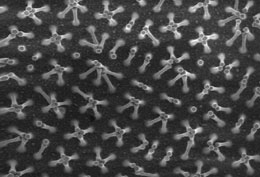

Gecko Tape

View the page for this story

Geckos are lizards with amazing stickiness, thanks to millions of tiny hairs that line their feet. Host Steve Curwood talks with Andre Geim, a scientist at the University of Manchester, who has modeled a dry adhesive tape on the gecko’s extraordinary ability. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note/Infrasound

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on research showing that extremely low sound vibrations called infrasound may lead to strange emotional and physical responses. (01:20)

The Politics of Petroleum

/ Sandy TolanView the page for this story

A giant gas-drilling project in the Peruvian Amazon was supposed to set a standard for environmental and cultural responsibility. But it lies in an indigenous area and since work began, it's raised questions. Part of a new series "Worlds of Difference" from independent producer Sandy Tolan and Homelands Productions. (15:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Andre GeimREPORTERS: Bruce Gellerman, Miriam Landman, Guy Hand, Sandy TolanNOTES: Cynthia Graber

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR - this is Living on Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Coming soon to a strip mall near you, fast food that’s good for you, and your waistline. As Americans become more concerned about health and less happy about getting fat, some organic entrepreneurs are setting out to change an industry.

HIRSCHBERG: As companies like O’Naturals grow we will force the MacDonalds, the Burger Kings, the Wendys to come to us. And frankly, they’re here. You’ll see them walking through and taking pictures, and frankly we welcome them.

CURWOOD: Also, from sight to sound - how choices change and expand when one shifts from capturing nature with cameras to capturing it with microphones.

DORRITIE: It’s time for the voice of the planet to be heard; it’s time for the voice of nature to be heard.”

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth Comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Fast Food O’Natural

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Let’s face it, we’re fat. Two out of every three Americans are either overweight or obese. And many say the culprit is fast food. Consumer advocate Ralph Nader calls the double cheeseburger a weapon of mass destruction. A growing number of consumers have seemingly gotten the message from the U.S Surgeon general that the supersizing of America is a public health hazard. Still, the hamburger reigns supreme at Burger King, MacDonald’s and the like. But a new breed of so-called “healthy fast food” restaurants is shaking up the nation’s food chain. Bruce Gellerman has our story.

GELLERMAN: Go to a typical fast food restaurant and you might find a poster of a colonel or a plastic clown greeting you. But visit O’Naturals and it’s possible you’ll be met at the door by president and chief executive officer Mac McCabe.

MCCABE: Hello.

WOMAN: Hi.

GELLERMAN: Do you always greet people at the door?

MCCABE: Yeah. You know, you’re only as good as your next customer, and you can have a great idea for a restaurant, but if the customer doesn’t have a great time there, they won’t come back.

GELLERMAN: O’Natural’s idea is to create a chain of all natural, organic “fast casual” restaurants. Right now it’s the first and only all-organic chain in the nation. Admittedly, O’Naturals is nothing more than a single sesame on a huge bun. There are only 4 O’Naturals. They’re all in New England. McDonald’s, by comparison, has 13,000 in the United States alone and serves millions of customers a day. But Mac McCabe sees those customers as naturals...for O’Natural.

MCCABE: You know, early on people would say, oh it’s a vegetarian restaurant. It’s like, no it’s a natural and organic restaurant.

GELLERMAN: But when somebody drives in – they don’t know this place – and you say vegan, you’re going to scare them to death.

MCCABE: Yes, but it’s sitting right next to a steak sandwich.

GELLERMAN: That’s a steak sandwich made from free range beef. It’s made with organic whole wheat flat bread baked right before your eyes. O’Natural’s doesn’t serve french fries – it serves organic heirloom roasted potatoes. There is bleu cheese, there’s brie. That’s not your typical fast food fare. Nor are Asian style noodles, or wild salmon, or bison burgers. The bison are harvested on Nature Conservancy land by Native Americans.

This may all sound like a throw back to the 60’s, but O’Naturals is anything but a hippie fast food fantasy. This is a consumer-tested business – from vegan soup to organic nuts.

HIRSCHBERG: I think part of what set out to do here is redefine what fast food is all about.

GELLERMAN: Gary Hirschberg came up with the concept for O’Naturals. He’s a legend in organic food circles. Hirschberg started out 20 years ago with 5 cows and an idea. Today, his Stonyfield Farm company is the largest organic yogurt company in the world. Hirschberg wants to apply the same principles to create a chain of healthy fast food restaurants.

HIRSCHBERG: I’m not going to tell you what’s healthy for you, but I am going to tell you that by being organic, there is the absence of bad stuff. I’m going to guarantee you that every drop of dairy in this place is made from cows who are not injected with synthetic hormones. I can tell you that every bite of bread is going to be pure organic.

And you know, a lot of people say organic isn’t proven, but the reality is it’s chemicals that aren’t proven

GELLERMAN : The O’Naturals concept doesn’t stop with food. It includes the restaurants. This one in Acton, Massachusetts has brown leather couches and wood chairs and table. Hirschberg says the restaurants are environmental statements.

HIRSCHBERG: It’s very important that the experience be green. The panels here is post harvest wheat chaff. We even have plastics here, on the tables that are made from recycled yogurt containers. We have all recycled materials. All the wood in the place. The doors and windows are taken from an old Naval air station – swords into plowshares I guess.

GELLERMAN: It’s an ambitious plan but it’s not unprecedented. Healthy fast food restaurants have been tried before. In the 1980s there was D’lites. The lite burger chain quickly grew to a hundred units. Then the company went belly up. McDonald’s came out with it’s McLean Deluxe a few years ago – that was a low-cal burger. It, too, was a belly flop. So were Taco Bell’s recent Border-lite offerings.

Robin Lee Allen is an editor at “Nation’s Restaurant News,” a trade publication that follows the fast food industry.

LEE ALLEN: The biggest problem is that consumers say they want one thing and then they choose not to buy it when it’s available. And it’s the perception, whether it’s right or wrong, that if things that are more “healthful,” they do not taste as good as things that come out of the deep fryer or come out laden with chocolate sauce.

GELLERMAN: But Robin Lee Allen says tastes and demographics are changing. Aging boomers want more than a burger these days. They’re increasingly health conscious, and their kids are more sophisticated about food. It’s a changing landscape, with more fast food restaurants that cater to health conscious consumers

[SOUND OF BLENDER]

GELLERMAN: Here at Fresh City in Newton, Massachusetts they’re whipping up a Berry Best smoothie. That’s a blend of strawberries and blueberries. I go for one with a so-called Stress Reducer. That adds ginseng, bee pollen and calcium to the mix.

Bruce Reinstein and his brother built their first Fresh City a few years ago. Now there are 11. Like O’Naturals, Fresh City serves up wraps, sandwiches, salads and stir-fries. It even has miso. Bruce Reinstein says the food at Fresh City is fresh, but it’s not organic.

REINSTEIN: You know, it’s nice to have healthy foods, but more importantly it’s nice to give people the options to what they want. Because people want to eat healthy but a lot of people want to feel they’re eating healthy, and it’s really up to them to decide what sauce, do they want sesame noodles on their wrap, or do they want simple jasmine rice. It’s really their choice.

GELLERMAN: But it can be difficult to choose the healthy from the potentially harmful. Fresh City does have many low cal, low fat offerings, but its Teriyaki wrap, while fresh, has as much fat as a Big Mac and nearly twice the calories.

LEE ALLEN: Because something is fresher doesn’t mean it’s necessarily more healthful.

GELLERMAN: Again, “Nation’s Restaurant News” editor Robin Lee Allen.

LEE ALLEN: I think what happens is that people get confused between – you’re talking about two different things –..one side is what’s more healthful, what’s low fat, what’s lower in calories, lower in sodium, lower in cholesterol – and what’s fresh. I mean you can have something that is fresh that is not necessarily low in calories.

GELLERMAN: Likewise you can have something that is organic that’s not necessarily low in calories. Still, public preferences are changing. Customers are telling the fast food industry that fast is no longer enough. They want their food fresh, healthy, and even organic. You can see it in the proliferation of new “good for you chains:” Healthy Bites Grill and Health Express. And you can see it in the reaction of McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Taco Bell and other fast food giants.

McDonald’s recently started serving a new line of salads and low-fat yogurt. And it’s entered a licensing agreement with Fresh City. McDonald’s now runs 6 Fresh City outlets. What’s more, McDonald’s is phasing out the use of antibiotics in its meat and trans-fatty acids in its fried foods.

Slowly, but surely, the fast food chains are changing their menus, and the nation’s food chain as well. Before, it didn’t matter so much what kinds of ketchup, cheese, and buns McDonald’s bought from its suppliers. Now it does, according to O’Natural’s Gary Hirschberg.

HIRSCHBERG: When I look at who has now launched organic in the last few year, it’s brands like Frito Lay, Heinz, Kraft. I assure you these folks are not coming to organic because they’ve suddenly had a religious experience. This is because consumers are asking for this stuff. We’re all reading labels.

GELLERMAN: Organics is now a $13 billion a year industry. It’s almost tripled in size in the past 3 years. And Hirschberg says the future is just as bright.

HIRSCHBERG: I think there’s no question we’re going to spawn a whole new generation of restaurants. But as companies like O’Naturals grow, we will force the McDonald’s, the Burger Kings the Wendys to come to us. And frankly, they’re here. You’ll see them walking through and taking pictures, and frankly we welcome them.

GELLERMAN: But they may have to stand in line. The average O’Natural’s restaurant makes more money than the average McDonald’s. If the trend continues, Hirschberg and his O’Natural chain could, one day, eat McDonald’s lunch.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bruce Gellerman.

CURWOOD: In the interest of full disclosure, one of the subjects of the healthy fast food story is the CEO of Stonyfield Farm, an underwriter of Living on Earth. Our story was independently edited by Ken Bader.

Commodified Oxygen

CURWOOD: Hindsight, they say, is twenty-twenty. And for critical issues such as air quality, commentator Miriam Landman hopes hindsight and foresight will win out over our typically shortsighted perspective. She brings us this wake-up call from the future.

[RINGING ALARM CLOCK]

LANDMAN: It’s a typical morning in the year 2020. I get ready for work by climbing into my full-body bubble suit. I zip it up and glance in the mirror to make sure my oxygen tank is on straight. Sound absurd? Well, we already buy bottled water, and we pay more for it than for gasoline. And on smoggy days we reach for our inhalers. And now, some of us even duck into an oxygen bar for a 20-minute hit of pure, unadulterated air.

The first time I heard of an oxygen spa, I was skimming through a magazine. There was an ad featuring a model with clear plastic tubes inserted into her nostrils. The ad was for the “O2 Spa Bar,” a stylish Toronto salon offering "oxygen sessions" for $16 a pop. The ad stated: "It may sound weird at first. But think about how much smog and car exhaust you breathe into your lungs every day."

Well, that certainly is something to think about. Unfortunately, instead of actually solving that problem, oxygen bars have sprung up all over the world— first in smoggy Asian cities like Tokyo, where there are also coin-operated oxygen booths on the streets, and later in Europe and North America. So when an air bar opened up in my fair city of San Francisco, I just had to go check it out.

[MUSIC: Telepopmusik “Breathe (Extended Mix) Breathe {CD-Single} Emi Int’l (2002)]

It was a long, dimly lit room that felt like a cocktail lounge. Twenty-something hipsters were lounging around on pleather couches, while a DJ spun ambient techno music. I sidled up to the bar and perused the menu of aromatherapy oxygen blends with names like Euphoric, Release, and Relax. I ordered a dose of Release from the bartender, and I asked him if I was about to get high. “I wouldn’t put it that way,” he said. “It just makes you feel better. And it lasts longer than the feeling you’d get from drinking a beer.”

Soon, I was hooked up a tank of the herbal oxygen concoction. There was a tube in my nose. I can’t say I felt as glamorous as I would had I been holding a martini, and I can’t say it actually did anything for me - other than inject the scent of Lavender into my nasal passage. But that’s not surprising, since there’s no sound evidence that oxygen spa treatments are at all effective in cleaning pollutants out of our lungs.

The original website for Woody Harrelson's Los Angeles oxygen bar declared: “Up your nose with a rubber hose” and “join the rest of society who laughed at the idea of bottled water.” It is hard to take oxygen bars seriously, but the implications are serious, as serious as a heart attack. Medical studies have found that breathing dirty air can actually trigger fatal heart attacks in people with cardiac problems. And roughly 17 million people, in the U.S. alone, suffer from asthma. That’s three times as many as there were twenty years ago.

Recently, I read a magazine blurb about a new high-fashion jacket that came equipped with a smog-filtering mask attached to its hood. Jackets with breathing masks and oxygen-hocking establishments, to my mind, belong in a bleak, futuristic, sci-fi world. But while we were sleeping, the future arrived. The surreal is now the real. So I can’t help but wonder: What’s next?

CURWOOD: Miriam Landman is a freelance writer and a green building consultant with Simon & Associates in San Francisco.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Just ahead: A picture may be worth a thousand words, but sound can make you speechless. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC]

Almanac/Spindletop

CURWOOD: Welcome Back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC]

The folks who gathered on Spindletop Hill this week back in 1901 had little idea they were about to witness the birth of the Age of Petroleum. Indeed when oil was struck at about 10:30 in the morning, the wife of the leaseholder had him hurry back from the barbershop in town. She was worried the oil would stop and he would miss all the action. But Spindletop didn’t stop.

It gushed for years, and would shoot one hundred and fifty feet into the air if it wasn’t capped. At the time oil was used mainly to make kerosene and to grease wagon wheels. It would take the automobile and its thirst for gasoline to make the oil business huge. Even so, thousands of boomers inundated the small southeast Texas town of Beaumont, eager to get their share of black gold.

The Spindletop oilfields produced millions of barrels per year until the salt dome that formed the hill was depleted. In the 1950s, the area was strip-mined for sulfur and today Spindletop looks like a swampy sinkhole. But, prospectors say there are still huge gas and oil reserves deep below the site and descendents of the original leaseholders still draw oil royalty checks to this day. And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC]

The Sounds of Nature

CURWOOD: Everything we know about the world – the smell of pine, the feel of granite, the glow of distant stars – comes to us through our senses. Photographer Guy Hand has found that favoring one sense over another can skew our perception of that world. He sent us this story from a nature sound recording workshop in the California Sierras, where he tried listening to a landscape he had up until then only looked at.

[SOUNDS OF WALKING OUTSIDE]

HAND: It's five in the morning, and I can barely see the pine trees on the far edge of the meadow, and the mountains beyond. Twenty of us stumble out of our cars, half-awake, sip coffee and flick flashlights over a tangle of gear: headphones, recorders, mics, cables.

MATZNER: Keep your headphones on when you're recording and put them around your neck when you're not.

HAND: I'm here to get advice on recording birdcalls and waterfalls from the experts, but also to make a little comparison. I've switched careers, sliding slowly from photography to radio, from sight to sound.

MATZNER: Let's meet back here at ten o'clock.

HAND: When I first began fiddling with sound recording, I was struck by the similarities it shared with photography. I didn't even have to buy a new equipment bag, I just stuffed the old one with microphones instead of lenses, with digital recorders instead of cameras.

MALE: Oh, I see, so that's actually an external way that you can monitor the volume control.

HAND: Through the darkness, I hear another thing sound recorders share with photographers: a love of technobabble.

MALE: It comes out of here and goes into this box, and lets me do the switching and the volume control.

HAND: This new vocation feels familiar because sound, like sight, is a recordable sense, the only two of the five you can catch on tape.

MALE: You're hearing the snipe now.

HAND: But it's different, too. In the field, as soon as I put the camera away and pull on a set of headphones, the world seems to shift.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

HAND: With a camera around my neck, I passed this meadow by a dozen times. I was oblivious to the swirling world of willets, swallows, snipes, and wrens.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

HAND: I wonder what else draws people to nature sound recording.

HAND (In the field): So why are you doing this?

STORM: Well, because it's fun, because it's music. We're making music with creation, with the natural world.

STUART: Well, I think you can really sort of get into the moment, when you're sitting with your headphones on, and the birds are around you, and you're just enveloped.

CHRISTOPHERSON: The real reason I come out here is ‘cause it's a good excuse to go out in nature and shut up. [laughs]

HAND: Shutting up is one of the things I really like about sound recording. It requires a kind of passivity, a willingness to settle in and let the world come to you. Photography, on the other hand, feels active to me, even predatory. After all, we use hunting terms to describe it: shooting pictures, taking photographs, firing off a roll of film. Maybe that's why when we really need to listen, we often close our eyes.

CHRISTOPHERSON: My family said, well, you're going to take the cameras? But no, no, this time I have no cameras. I'm not going to be distracted by the visual images. I'm going to just go for the sound images.

HAND: Arlyn Christopherson is only the first of many here who bring up photography as a potential distraction. They say that sight too often dominates sound, and in effect blinds us to all the other senses.

MATZNER: There's so little attention put in the world of sound, even when natural history is the topic.

HAND: But Paul Matzner, curator of the California Library of Natural Sounds and one of the workshop leaders, reminds me that sound can also be distracting.

MATZNER: Many people in the large cities like New York, they wake up every morning to the huge sounds of garbage trucks out in the streets at five in the morning. They wake up at the same time as our ancestors would have woken up to bird song.

HAND: Paul puts a finger to his lips, then cocks his head to a birdcall he can't quite identify.

MATZNER: Uh…

HAND (In the field): Hear something?

MATTSNER: Yeah, I’m listening…

HAND: It takes him a moment to shift back to our conversation.

MATZNER: Um, I think that what sound recording does, and what the workshop does, is it helps to give us back our ears.

[LOUD MACHINERY NOISES]

HAND: I know what Paul means. Just getting to this workshop required I run the auditory gauntlet of the Reno, Nevada airport, with its slot machines, canned music, and crowds.

[CROWD NOISES]

HAND: But this forest of noise also made my arrival to the banks of this mountain stream that much sweeter.

[STREAM NOISES]

STORM: One of the nicest places where you'll find delicate and beautiful water sounds are where the gradient is very shallow.

HAND: Jonathan Storm is trying to teach our group how to listen to the sounds of water.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

HAND: The way he floats over this stream, ear tuned to every little ripple and rill, I can't help but catch the excitement of seeing his eyes. I wonder why more people aren't hooked on the musicality of moving water. STORM: It has a really nice low frequency, some mids and highs. It has a typical water sound people will recognize, as well as a little unusual water sound that people might not recognize. HAND: As Jonathan critiques the creek, Rudy Trubitt, another veteran sound recordist, tells me why he thinks a picture of a stream is easier for most of us to appreciate than the recorded sound of that same stream. TRUBITT: If you're looking at a piece of videotape and you pause the tape, what do you see? Well, you see a still image. If you're listening to a sound recording and you pause that sound recording, you hear silence. There is no way to experience an instant in sound, and spread that experience out over time in the same way that you can stare at a painting or a photograph for as long as you want. So that makes sound unique, in that it's more ephemeral. STORM: That single little bit where it's bouncing up over the rock, and the air underneath it… TRUBITT: Yeah, that little burbling. STORM: That's making the burbling. That's pretty loud, though. HAND: I begin fishing this high Sierra stream with my recorder, trying to hook the perfect little burble with a dangling microphone. But after an hour or so, boredom starts to seep in, like water into my boots. I mean, who is really going to listen to my little collection of slurps and gurgles anyway? But Frank Dorritie says, you never know. DORRITIE: Every time you roll tape you're making a historical document. Some are more important than others, but some of them are really important. Some of them are profound. HAND: Frank is a Grammy-winning audio producer and trumpet player. He reminds me that nature sound recording can capture nothing less than the fading voices of endangered species or the quiet call of some as-yet-undiscovered wonder. DORRITIE: This is powerful stuff. You don't trifle with this. This is important, visceral…

|