December 17, 2010

Air Date: December 17, 2010

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Mixed Results From the Climate Summit in Cancun, Mexico

View the page for this story

The international climate talks in Cancun wrapped up with a deal that many categorize as a moderate agreement that helped put confidence back in the negotiation process. Alden Meyer, Director of Strategy and Policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists, tells host Steve Curwood about the progress made in Cancun and what negotiators will need to prioritize in South Africa next year. LOE also speaks with Grenada Ambassador Dessima Williams about the Cancun agreement. (05:00)

Killed by the Messenger

View the page for this story

It’s long been said the medium is the message. But psychology and marketing professor Robert Cialdini says that sometimes those who produce environmental messages ignore the social science of how people think and respond. He talks with host Steve Curwood. (07:00)

The Wild Weather of 2010

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

Drought, flood, record heat and record snow--this year had it all. Living on Earth’s Jeff Young asks weather experts whether climate change pushed these extreme events. Their answers carry a warning about the weather of the future. (11:00)

Mastodon Found in the Rockies

/ Mitzi RapkinView the page for this story

People in the Rocky Mountain west are accustomed to finding treasure in the ground — gold, silver, oil & gas. But outside the ski mecca of Snowmass Village, archaeologists struck a rich vein of another kind. Mitzi Rapkin reports. (04:30)

BirdNote® - Winter’s Regal Visitor

View the page for this story

The large, majestic Gyrfalcon is no snowbird. This falcon lives and breeds in the Arctic tundra and sometimes heads to the northern states of North America for the winter. Mary McCann has this BirdNote®. (02:00)

The Legacy of David Suzuki

View the page for this story

Over the span of a lifetime, the world’s population has tripled and consumption has become a way of life. David Suzuki reflects on these changes in his new book “The Legacy: An Elder’s Vision for Our Sustainable Future.” He tells host Steve Curwood that the path to a sustainable future is to stop elevating economy over ecology and to start imagining a brighter future. (16:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Dessima Williams, Alden Meyer, Robert Cialdini, David Suzuki

REPORTERS: Jeff Young, Mitzi Rapkin

BIRDNOTE: Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. International climate negotiators have packed their bags and left Cancun. There’s a little more hope for progress when they meet next year in Durban, but experts warn their action plans are falling short.

MEYER: Time is running out and the atmosphere doesn't negotiate with politicians. And, we're getting closer to some of those tipping points that scientists warn us about. So, we have to accelerate the pace of change and action.

CURWOOD: Also, floods, heat waves, droughts— experts say 2010 was one for the wacky weather record books.

MASTERS: In my 30 plus years of being a meteorologist I can’t ever recall a year like this one as far as extreme weather events go. This year makes me nervous, it really does.

CURWOOD: What the year’s weather extremes suggest about climate change. We’ll have these stories and more just ahead right here on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[THEME]

Mixed Results From the Climate Summit in Cancun, Mexico

Alden Meyer is director of strategy and policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists.

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Next year’s climate summit is in South Africa. But what, in fact, was accomplished last week in Cancun? Well, there’s a deal to fast track lots of money to developing countries, and there’s a non-binding agreement to limit the warming of the earth to two degrees centigrade.

But the biggest accomplishment may have been renewed credibility for the UN process. As she boarded a bus after the summit, I asked Dessima Williams, she’s chair of the Alliance of Small Island States, for her assessment of deal struck in Cancun.

WILLIAMS: It’s a start. It’s a recovery mainly – it’s a recovery from the gloom and the pessimism of Copenhagen and what it does is that it restores our preparedness to work together, it prepares our faith in the multi-lateral system, and it puts some concrete initiatives on the table.

CURWOOD: For the first time a black nation will be chairing the climate negotiation process. How will South Africa do?

Dessima Williams is the Grenada representative to the United Nations. (AOSIS)

WILLIAMS: Well I can’t answer that until we go there, but I know that what has happened now, in the 21st century, is that there is a large group of middle-range countries, such as the Mexicos and South Africas of the world. And, they’re taking over control of certain strategic elements in international relations from the North. I expect South Africa will do very well. They have already a very strong set of initiatives for climate resilient development. So, we’re really looking forward to Africa benefiting, in terms of adaptation and financing from the conference that will be held in South Africa.

CURWOOD: How much do you believe the finance package here?

WILLIAMS: It’s only a start. We had a very bad year with the fast start, which was supposed to be ten billion dollars out the door – I don’t think any of that was really spent. So, I think financing remains critical because it has to correct the damage done, and it has to spark and get us out of poverty, so financials will be absolutely important for South Africa.

CURWOOD: Dessima Williams is Grenada’s ambassador to the UN. Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientists is a long-time observer of these international negotiations. He says the deal in Cancun left it up to negotiators in South Africa next year to tackle one central issue.

MEYER: There’s a huge gap between the level of emission reduction commitments and pledges that are on the table now from countries like the U.S., Japan, Europe, Canada, India, etc., China, and the two degree Celsius temperature increase limit that they established as a goal to stay below. There’s a huge gap there between what’s on the table and what’s needed to stay within that temperature limit, and they really didn’t make much progress on addressing that.

Alden Meyer is director of strategy and policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists.

CURWOOD: So, some people said that the U.S. was once again the skunk at the picnic. There had been hope that the Obama administration would take action, that the U.S. would take action, but now once again the United States is the principal obstruction to really getting a worldwide agreement. How fair is that analysis?

MEYER: Well, I think on the legal form issue, it is fair, because I think even the administration had to acknowledge privately that the prospects of getting Senate ratification of any new treaty are pretty remote. The administration did continue to say though, that it will push for meeting the 17 percent reduction target the President put on the table in Copenhagen, even despite the absence of action by the Congress on a comprehensive climate bill.

They talked about how they would use existing executive authority in places like DOE, Environmental Protection Agency. I think obviously there will be a credibility issue on that over the next year if you see the Republicans and other opponents of Environmental Protection Agency actions succeed in handcuffing the administration’s ability to use that authority. The other big issue, of course, is climate finance, and there again the administration is struggling a little bit. They aren’t getting the increase they want, at least so far in the 2011 budget cycle, and of course when the Republicans take over the House next year, the prospects of getting a further increase in the 2012 budget request are pretty remote.

The interesting thing was, they came into this negotiation because of the failure of action in the Congress last year, in a weaker negotiating position than they were in Copenhagen last year. But, it didn’t seem to stop them from putting some pretty strong demands on the table for others, particularly for China and other developing countries.

CURWOOD: From what I saw in Cancun, it seemed that the U.S. and China were making nice. What did you see?

MEYER: I think that there was a clear shift between the atmospherics in Tianjin, which was the last meeting before Cancun in October, where there was a lot of rhetorical back and forth and bluster. For example, the head negotiator for the Chinese at the end of that week told a press conference that the U.S. was like a pig preening in the mirror. It got pretty down and dirty towards the end there. And, I think both sides consciously pulled back and tried to take a more constructive tone, I think both sides felt a little that the rhetoric that was getting overheated on climate was starting to affect the overall relationships.

But, the issues aren’t getting any easier. The problem as you know, Steve, is that the atmosphere doesn’t negotiate with politicians and we’re getting closer to some of those tipping points that scientists warn us about. So we have to accelerate the pace of change and action. Can we get enough done in time to really deal with what the science is telling us that we have to do, and there I think the jury is still out.

CURWOOD: Alden Meyer is the strategy and policy director for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thank you so much, sir.

MEYER: Glad to be with you Steve.

[MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Related links:

- Union of Concerned Scientists

- AOSIS Alliance of Small Island States

Killed by the Messenger

CURWOOD: Scientists are clear that in the not-too-distant future, we humans need to reduce our carbon dioxide emissions down to zero. But there’s a major disconnect between the scientific urgency, and what most of us feel in our daily lives.

Maybe marketers or psychologists could help get the message across. And one expert who’s thought a lot about environmental messaging is Robert Cialdini. He’s professor emeritus of psychology and marketing at Arizona State University. I asked Professor Cialdini why the urgency of the climate message wasn’t getting people to act.

CIALDINI: I think it has to do with a fundamental communication error that we are making. And, that is to describe the problem of so many people failing to take energy conserving action. We decry the widespread nature of these counter environmental actions that every one around us is taking.

And, we think that by making the problem seem so widespread that everyone will marshall their forces against it. What we forget is that there is a sub-text message that says ‘look at all of the people who are doing this wrong.’

The sub-text message is ‘look at all the people who are doing this wrong.’ And that message of what those around us are doing is a more primitive and a more powerful message than those having to do with approval or disapproval. What we have to do is emphasize all of the people who are doing this right, rather than all of the people who are doing this wrong.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, some of your work involves looking at what you call ‘the norm of reciprocation,’ I guess, the notion of what we’re not supposed to take without giving in return. Now what significance does that norm of reciprocation have with respect to people’s behavior say, with regard to the environment or climate change?

CIALDINI: Great question. The norm for reciprocation, as you say, is deeply felt. And, it turns out to be universal. There is no human culture that fails to train in its members from childhood in this rule that says you must not take without giving in return.

You must not receive without giving back for what you have received. And, we actually showed that in one of our hotel studies with the use of towels. We compared a sign that said, ‘if you will reuse your towels, we will give a donation to an environmental cause.’ That produced no increase in reuse of towels, compared to a sign that just said, ‘do this for the environment.’

But, we had another sign in this experiment that said, ‘we’ve already given to an environmental cause in the name of our guests. Would you reuse your towels to help us cover the expense.’ That produced a 19 percent increase in towel reuse. So people wanted to give back after they had received something.

Well here is the larger point that I think is available to be made from those data. You know, you’ve heard a lot of people say, ‘I’m entitled to use this energy, I worked for it, I made my contribution to this society. I can buy a Hummer if I want to.’

In other words, they’re saying, ‘I acted first, and so I’m owed something in return.’ What I think a legitimate counter-message would be, to that kind of thinking, is: ‘you didn’t go first. Nature went first. The earth went first. You have been given a set of resources so rich, so extensive that it’s your turn now, by the rule for reciprocation, it’s your turn now to give back and to be a steward of those resources.’ That’s a message that I think would be worth trying out.

CURWOOD: Okay! The climate activists come to you to design a campaign, a message, to get America and Americans aboard taking climate action. What’s the ad that you’d put together for this campaign?

CIALDINI: We’ve actually run some ads. We created three public service announcements to be run in Arizona communities. We had three components to the message. The majority of Arizonians, the people around you, approve of recycling. That’s one message. The second was: the majority of Arizonans do recycle. Both of those were true. And, the third was: the majority of Arizonan’s disapprove of the few who don’t recycle.

CURWOOD: Ooh! Ooh. That’s tough.

CIALDINI: And, we depicted scenes of individuals all recycling, approving of one another, and then identifying one individual who wasn’t recycling, and expressing disapproval of that individual. So, the key here was not to normalize the incorrect conduct, but to marginalize the incorrect conduct. And, those messages produced a 25.1 percent increase in recycling tonnage in the communities where they were played. Now, I don’t know how much you know about public service announcements, but that’s unheard of. If you get a one to two percent deflection in behavior from a PSA, that’s considered a success.

CURWOOD: Robert Cialdini is the author of “Influence, the Psychology of Disusasion,” as well as several other books on the science of persuasion, and also a professor emeritus of psychology and marketing at Arizona State University. Professor Cialdini, thank you so much for taking this time.

CIALDINI: I enjoyed it Steve!

CURWOOD: You persuaded me! And, you can hear more of Professor Cialdini’s interview at our website L-O-E dot org.

Related links:

- Click here for an extended interview with Robert Cialdini

- Cialdini on Environmental Messages

- Cialdini Twitter feed

- Professor Robert Cialdini

The Wild Weather of 2010

A satellite image of Russian forest fires.(NASA)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. The other day it was colder in southern Florida than northern Maine, while some western states had just set daily records for high temperatures. It’s been that kind of year-- extreme. Twenty-ten is bidding to go in the record books as one of the warmest, but it’s the craziness of the weather, rather than just the heat that has scientists concerned. Twenty-ten, they say, stands out for the number and intensity of extreme weather events. It appears climate change is tilting the odds in favor of more of the kind of heat, floods and even snows that 2010 brought us. Living on Earth’s Jeff Young has our story.

YOUNG: Jeff Masters has seen some pretty wild weather. As a hurricane hunter in the late ‘80s, he flew into the teeth of some of the biggest, baddest storms. Then he co-founded the internet forecasting site, Weather Underground. There he keeps track of extreme weather events. And Masters says 2010 is the most extreme yet.

MASTERS: In my 30 plus years of being a meteorologist I can’t ever recall a year like this one as far as extreme weather events go, not only for U.S. but the world at large.

YOUNG: Countries covering one fifth of the planet’s land saw record high heat. Drought altered the world’s food trade. Floodwaters inundated parts of the U.S. and Asia with frequency that defied statistical expectations.

TRENBERTH: Isn’t that interesting, we have a one in a thousand year event happening every few years nowadays.

YOUNG That’s Kevin Trenberth, a meteorologist who leads the Climate Analysis Section at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado.

TRENBERTH: And so, it’s the changes in extremes where we notice the climate change. Droughts and floods and heat waves that are outside the bounds of what we’d normally expect. The global warming component is rearing its head in that way.

YOUNG: And 2010 could be a harbinger of things to come, says Heidi Cullen, a climatologist with the non-profit research group Climate Central.

CULLEN: I actually do get a sense that we are really getting glimpses of what the future will look like through some of these extreme events that we’ve experienced.

YOUNG: I asked these three experts, Cullen, Trenberth and Masters, to choose their top examples of the year’s weather extremes. Their list tells us a lot about the interplay of climate change and weather. And it carries a warning about the storms on the horizon for coming generations.

[SOUNDS OF SNOWBALL FIGHT]

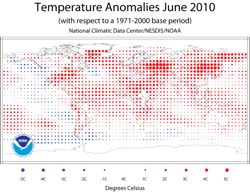

Feeling the heat: A NOAA map showing temperature anomalies this

June. (NOAA)

YOUNG: Remember snowpocalypse? Snowmageddon? Those monster storms dumped record piles of snow on the mid-Atlantic, including Washington D.C.

[SOUNDS OF SNOWBALL FIGHT CONTINUE]

YOUNG: This snowball battle in Washington’s Dupont Circle wasn’t the only fight the snow brought on.

CBS SNOWSTORM NEWS CLIP, SAWYER: That war of words over what this storm means for global warming…

LIMBAUGH CLIP: It’s one more nail in the coffin for the global warming thing.

YOUNG: The Capitol’s most prominent climate change denier, Oklahoma Senator James Inhofe, got attention with an igloo on the national mall.

INHOFE: They put a sign on top that said Al Gore’s new home!

YOUNG: But climate expert Kevin Trenberth says the Senator’s take on the storm is, well, a bit of a snowjob. Increased precipitation events— whether rain or snow— are just what computer models of climate change predict.

TRENBERTH: That’s actually very much a symptom of warmer sea temperatures off the coast that are providing extra moisture to produce that huge amount of snow. It’s not a sign that global warming is not here, quite contrary in fact.

YOUNG: That extra moisture and warm temperatures kept feeding severe storms in the U.S. Nor’easters soaked New England in late March; a deluge hit coastal North Carolina in October; record rains fell in Oklahoma City in June; and, in May, disaster struck Tennessee.

NEWS CLIP: Massive flooding left at least a dozen dead. Thousands of people have been evacuated after an astonishing 13 inches of rain fell in a two-day period.

MASTERS: That rain event was equivalent to a one in 1000 year event.

YOUNG: That’s Weather Underground’s Jeff Masters.

MASTERS: You have to go back to the civil war to look at any kind of disaster that effected Tennessee as great. The city of Nashville was basically underwater. And I might add that the record high temperatures were set up and down the coast in the few days accompanying that storm event. And, again, when you have record high temperatures you can have record amounts of water vapor present in the atmosphere capable of causing heavy rains.

YOUNG: By mid summer it was the heat Masters was tracking, first in the eastern U.S.

MASTERS: Well, the record heat was concentrated in mid Atlantic region again, so not only did they have snowmageddon, but they had their hottest summer on record in the DC area. Maybe the legislators there were trying to be told something! I don’t know…

YOUNG: Then in September the West Coast felt the heat.

NEWS CLIP: A record-breaking heat wave making LA feel more like Death Valley. In downtown Los Angeles yesterday, thermometers topped out at 113 degrees, an all time high.

YOUNG: Through October, more than 41 hundred record highs were reported around the U.S. About 15 hundred record lows were posted in the same time, a high-to-low ratio of about two point five to one. But the U.S. heat wave paled compared to what much of the rest of the world endured this summer.

NEWS CLIP: Forest fires have killed at least 25 and left thousands homeless in central Russia as heat wave grips much of the country.

A satellite image of Russian forest fires. (NASA)

YOUNG: Moscow had never before hit 100 degrees. This summer, it hit that mark 5 times in ten days. Again, Climate Central’s Heidi Cullen:

CULLEN: What we saw happen in Russia this summer was so fascinating, because we saw it had global reach, right. They stopped exporting wheat; they lost essentially 30 percent of their wheat yield. And, from a statistical standpoint, those kinds of statistics just fascinate me. When you look at the July temperature anomaly in Moscow since 1950, technically, it was essentially like a one in 100,000 year event that’s how intense it was. I mean it was just off the charts.

YOUNG: Eighteen countries set records for high temperatures. Jeff Masters mapped them as the extreme heat covered more and more of the planet.

MASTERS: The warm temperatures covered a record amount of the earth’s surface. We’ve never seen 20 percent of the earth’s surface experience their all-time record high in one year. Now, that’s not to say every point in those country set an extreme record, but certainly in Russia, a good portion of Russia hit their all time extreme records. In Pakistan they hit 128 and a half degrees Fahrenheit, which is the hottest ever recorded in Asia. And, Southeast Asia hit its highest with Burma over 116 degrees this summer.

YOUNG: Masters says the same rare weather pattern that baked Russia—a sort of kink in the jet stream over Asia—also had another effect.

MASTERS: And so, again, all that heat allowed for more water vapor to evaporate into the air and caused heavier precipitation than would have otherwise would have happened.

NEWS CLIP: Southern China has been devastated by floods and landslides caused by weeks of torrential rain. In Schizuan province some parts were hit with the heaviest flooding in more than 150 years.

YOUNG: First China, then, Pakistan. Some 20 million people were affected in Pakistan, as roughly a fifth of the entire country was underwater.

Pakistanis fleeing floodwaters. At one point, one-fifth of the nation was underwater. (UN Development Programme)

MASTERS: In Pakistan it was that nation’s Katrina. It was their worst natural disaster in history.

YOUNG: This is by no means an exhaustive list for 2010’s weather extremes. The Atlantic hurricane season was also very active, and the Pacific saw a shift from the periodic warming known as El Nino to the cooling called La Nina. What climate and weather experts like Masters, Cullen, and Trenberth see in this year’s wild weather is a mix of natural variability and a changing climate. NCAR’s Kevin Trenberth says the natural variability still reigns supreme.

TRENBERTH: But the global warming signal is always in the background and always going in one direction. And, it’s when the natural variability is going in the same direction as the global warming that we’re suddenly apt to break the records.

YOUNG: So, journalists seem especially prone to asking this question when there is, say, a big flood or heat wave, and we want to know is this global warming-- What do you say?

TRENBERTH: That’s really not the right question because we can’t attribute a single event to climate change, but I would contend that every event has a climate change component to it nowadays. And a different way of thinking about it is try to look at odds of that event happening. And, with some of the events that we’ve had this year it’s clear-- even though the research has not been done in detail yet-- that the odds have changed, and we can probably say some of these would not have happened without global warming, without the human influence on climate.

YOUNG: Climate Central’s Heidi Cullen agrees. She likes to say, there’s no lone gunman theory of climate change causing weather events. But the data can reveal warming’s extra push. That’s just what scientists were able to do in a study of the deadly heat wave that gripped Europe in 2003. Cullen says they ran two models, one with a steady, unchanging climate, another with a climate altered by greenhouse gas emissions.

CULLEN: In that world where we have had our fingerprint through fossil fuel burning and deforestation, that world produced a heat wave like the one we saw in Europe with a much greater frequency. So, global warming doubled or possibly quadrupled the chances of that event happening.

YOUNG: Cullen writes about that study in her book, “The Weather of the Future.” She explores what studies like that can tell us about the weather to come.

CULLEN: They showed that by 2040 the 2003 type summer we saw in Europe would likely be happening every other year. And by 2070 the European heat wave of 2003-- that would be a relatively cool summer. And so I think that when you do that thought exercise and fast forward through time, you begin to really see how big of a problem this becomes for society.

YOUNG: That 2003 heat wave, Cullen reminds us, killed more than 30 thousand people and cut crop harvests by nearly a third.

MASTERS: This year makes me nervous, it really does.

YOUNG: A closing thought from Weather Underground’s Jeff Masters.

MASTERS: Two thousand ten could very well be the sign that the climate is beginning to grow unstable. That’s what we’re bequeathing to our kids. I have a 14 year old as well, that I think is going to be looking back fondly on years like 2010 saying, ‘Oh, it wasn’t so bad back then.’

YOUNG: You can hear more from these weather experts and see the weather and climate data and studies mentioned in this story at our website L-O-E dot org. For Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young.

Related links:

- Extended interview with Jeff Masters on the wild weather of 2010, how melting Arctic ice affects US weather, and how climate change is “loading the dice” for the chances of extreme weather.

- Jeff Masters Wunderblog of extreme weather at Weather Underground

- Heidi Cullen’s Climate Central

- Latest research from Kevin Trenberth and his colleagues at NCAR’s Climate and Global Dynamics

- NASA analysis of 2010’s heat

- Comparison of record highs and lows in the US

- NOAA Analysis of Russian heat wave

- Study of global warming’s contribution to the 2003 European heat wave.

Mastodon Found in the Rockies

Left to right museum chief curator Kirk Johnson, excavator Dane Miller and curator Ian Miller with the tooth of an American mastodon.

CURWOOD: Snowmass Village, Colorado, is perhaps best known as a first-class ski resort high in the Rocky Mountains. But soon, it could also become known for one of the most significant finds of ice age fossils in North America. From Aspen Public Radio, Mitzi Rapkin reports on the bounty of bones.

RAPKIN: Winter has arrived in Snowmass Village and with it, deep snow. But, researchers look forward to spring when they will return to an excavation site that riveted paleontologists and the just plain curious around the country.

TV NEWS ANCHOR: Scientists are calling it one of the most important and most exciting fossil finds ever in Colorado, already…

RAPKIN: The discovery includes nearly 600 bones so far. In this area that used to be mined for silver, the dig site is a fossil mother load.

MILLER: Columbian mammoth, American mastodon, uh, giant ground sloth, bison, tiger salamander. I’m missing one, oh and a deer.

RAPKIN: That’s Ian Miller, curator of paleontology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. It’s not necessarily unique to find so many ice age fossils in one place, but remains of these animals have never been found at such high altitude, or with such diversity, in the Rocky Mountains. Miller:

Left to right Kirk Johnson, Dane Miller and Ian Miller unearth the latest find at the Snowmass mother lode. (Photo Mitzi Rapkin)

MILLER: So, there’s no record of what was living here so we’ve been inferring what was living here at high elevation from other places. So it’s so great to have this Pleistocene graveyard at nine thousand feet. It’s really giving us some insight into what Colorado was like say 40, 50 thousand years ago.

RAPKIN: This ice age graveyard is geologically special, which likely accounts for the diversity of large mammals and the time period they represent. It’s an old lake that scientists estimate was formed 120 thousand years ago. It sits on top of a ridge, so it filled in slowly and wasn’t destroyed by subsequent glaciers.

These discoveries were a fluke. That ancient lake is now a municipal reservoir that happened to be under construction. Jessie Steele was running the yellow iron – that’s what he calls his bulldozer – when he noticed something unusual.

STEELE: There was two rib bones that come up in the dirt on the dozer to start with and as soon as I shut down and got out, I noticed there was a considerable amount more. I’m an avid hunter also, and so I could tell right away they waw ribs. I did not know what in the world they was off of…

RAPKIN: You knew it wasn’t a deer?

STEELE: No ma’am, it was not.

RAPKIN: From the day Steele found the ribs it was non-stop action at the site. More than 40 people dug at a time. The site also had 24-hour security to protect it from looters.

Kirk Johnson is the Chief Curator of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, which is in charge of the excavation. The site is so rich with bones, his crew practically finds them on demand for visitors.

[DIGGING SOUNDS]

Left to right museum chief curator Kirk Johnson, excavator Dane Miller and curator Ian Miller with the tooth of an American mastodon. (Photo Mitzi Rapkin)

JOHNSON: There’s got to be a bone, here.

MAN 1:It looks like a tooth! Oh yea, it is…

MAN 2:it looks like it’s attached to the jaw here…it could be the mandible. Or, maybe it’s the skull.

JOHNSON: So this is like four by two and a half inches, about a pound, one tooth off an American Mastodon.

RAPKIN: Johnson says the fossils are in exquisite condition.

JOHNSON: We’re getting leaves that are still green. We’re getting beautiful preservation of the bones. The wood that comes out of the ground looks like driftwood, we’re finding chunks of beaver chewed sticks, and cones of spruce and fir, skeletons of little salamanders. So it’s a real well-preserved fossil treasure trove.

RAPKIN: It will take at least a year to slowly dry out the bones so they don’t disintegrate. They’ll still be drying when scientists return to the site in May to continue excavating. Now the town is trying to figure out how to market the find to draw tourists. The town council even adopted an official song, Big Wooly Mammoth. Many, including Johnson, also say it’s time for a name change in the town…

JOHNSON: They’ve got to change the name of this town. Snowmass is boring, Snowmastodon is accurate.

RAPKIN: For Living on Earth, I’m Mitzi Rapkin in Snowmass Village, Colorado.

CURWOOD: And if you’re curious what those bones look like, you can see one massive mastodon tooth at our website, L-O-E dot ORG.

Related link:

Denver Museum of Science and Nature dig website

BirdNote® - Winter’s Regal Visitor

Gyrfalcon. (Photo: Tom Munson©)

CURWOOD: This time of year, some folks flock to warmer climes, earning them the nickname “snowbirds.” But there are some birds of the feathered kind, who like cold winters and Mary McCann tells us about one in this week’s BirdNote.

Gyrfalcon. (Photo: George Vlahakis©)

[SOUND OF THE WINTER WIND]

MCCANN: Winter sends wondrous birds down from the Arctic. Unrivalled among these visitors is the majestic Gyrfalcon. Gyrfalcons are among the largest falcons in the world, with the female—the larger of the sexes—outranking even a Red-tailed Hawk in size.

[GYRFALCON CALLS]

MCCANN: With a name that derives from an Old Norse word for “spear,” the Gyrfalcon was a medieval falconer’s prize, reserved for royalty. Kublai Khan, it is said, kept two hundred. When hunting, the Gyrfalcon flies swiftly, and low, over the ground, hugging contours to conceal its attack. A Gyr’ is capable of overtaking even the fastest waterfowl, some of which can fly 60 miles an hour.

Gyrfalcon. (Photo: Tom Munson ©)

[SOUND OF THE GREATER SCAUP IN FLIGHT]

MCCANN: On its summer range on the tundra, the falcon feeds mostly on ptarmigan. But in winter, it is opportunistic, chasing down shorebirds, ducks, partridges, and even small rodents. By December, a small number of Gyrfalcons have flown south to the northern states, where they will spend the winter in areas of open expanse, such as farmlands or coastal areas.

[GYRFALCON CALLS]

MCCANN: For BirdNote, I’m Mary McCann.

CURWOOD: To see photos of the Gyrfalcon, fly on over to our website L-O-E dot org.

Related links:

- Call of the Gyrfalcon and Greater Scaup provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Call of Gyrfalcon recorded by A.L. Priori. Call of Greater Scaup in flight recorded by W.W.H. Gunn.

- BirdNote® - Majestic Gyrfalcon – Winter’s Regal Visitor was written by Bob Sundstrom.

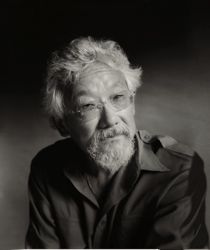

The Legacy of David Suzuki

Acclaimed scientist and environmentalist, David Suzuki. (Photo: David Suzuki)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. David Suzuki was a young child when the Canadian government incarcerated his family in a remote camp in the Rockies during World War II. And, because he couldn’t speak Japanese like the other interned kids, he went outside on his own and discovered nature. That experience led to an award-winning career in science and popularity as a nature and environmental storyteller on Canadian radio and television.

Recently David Suzuki compressed a lifetime of learning and doing into a single lecture and a, brief, astonishingly readable and uplifting book called “The Legacy: An Elder’s Vision for our Sustainable Future.” He joined us to talk about that vision. David Suzuki – welcome to Living on Earth!

SUZUKI: Hi!

CURWOOD: On the cover of your book “The Legacy: an Elder’s Vision for Our Sustainable Future,” you have a maple seed, the little thing that spins as it falls to the ground from a maple tree…

David Suzuki’s new book, “The Legacy: and Elder’s Vision for a Sustainable Future.”

SUZUKI: Right. Yeah, to me, that seed symbolizes an opportunity for us to try to copy nature. You know, trees can’t get up and try to drop their seeds all over the place, like an animal might, and so they’ve got to rely on methods to get their seeds spread away. And, one method of course is to use the wind and the air, and take your seeds and move them by this helicopter-like motion. One of our problems, I think, is that we try to overwhelm nature with the power of our crude technologies, and oftentimes it creates ecological problems. Nature’s had four billion years to evolve basic solutions to the same things you and I have: you know, how to keep from being eaten, what to do if you get sick, how do you get laid, I mean- if we were to look to nature, we could learn a lot with far less deleterious effects.

CURWOOD: Earlier in your book, you mention that the population of the world has tripled in your lifetime. That’s a pretty striking statistic. And, what does it tell us?

SUZUKI: It’s staggering. We appeared as a species in Africa, maybe 150,000 years ago. We wandered nomadically and gathered food and shelter. It was 10,000 years ago that the big change happened when we discovered agriculture. At the beginning of the agricultural revolution it’s estimated that there were about ten million of us on the entire planet. Agriculture heralded a huge shift because we could now grow our food dependably and in only 8,000 years, we increased to another order of magnitude to 100 million people. And then, in just over 1,800 years, we increased to a billion people. And then in less than 200 years we reached six point nine billion people in 2010. And, so, if you were to plot that on a piece of graph paper, the curve is essentially leaping straight off the page in the last pencil width of time. Nothing can go straight up off the page indefinitely. There’s got to be limits, and I fear, that we’re going to have some major problems of a big human die-off.

CURWOOD: So, yes, what is the problem of population? What are the consequences that you are concerned about?

SUZUKI: Well, of course it’s not just a function of number. It’s the amount of stuff that we exploit out of the biosphere, per person. So, if we in North American want to compare ourselves to China or India, you’ve got to multiply our populations by at least 20, to get our equivalent impact as Chinese or Indians. If you want to compare us to Bangladesh or Somalia, you’ve got to multiply by at least 60.

And, when you look at it that way, then it’s clear that it’s the industrialized world because of our hyper-consumption. We are consuming over 80 percent of the planet’s resources even though we’re only 20 percent of the world’s population. We are the major predator on the planet.

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about the economy. In your book, you quote a couple of economists and retail analysts. One of them is Victor Lebow. You quote him as saying, “Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life. The measure of social status, of social acceptance, of prestige is now to be found in our consumptive patterns.” And he goes on to say that, “The greater the pressure upon the individual to conform to safe and accepted social standards, the more he does tend to express his aspirations and his individuality in terms of what he wears, drives, eats, his home, his car, his pattern of food serving, his hobbies.”

SUZUKI: Isn’t that incredible? This is Victor Lebow who is an industrialist. What happened was we all came through the terrible depression after the stock market crashed in 1929. What got us out of the depression was WWII, and by the middle of the war, the American economy was blazing, white hot, pumping out guns and tanks and planes and weapons. And, of course, it was clear by the mid-1940s that the Allies were going to win the war, and people began to say, ‘well, what the heck do we do in peace time?’

And the president of the United States established the council of economic advisors to the president and said, ‘how do we make that transition?’ And the answer came back- consumption. And, Victor Lebow’s statement is just the plainest statement that you can get. We’ve got to make consumption an American way of life. Get people to buy stuff use it up, throw it away, and buy more stuff. And, once you introduce the concept of disposability, use something once and throw it away, you’ve got a perfect system, because you never run out of a market.

But of course, all that stuff is coming out of the biosphere and the emissions to make that stuff goes back into the biosphere, and when you’re finished with these products, you throw it back into the earth, and it’s creating an enormous ecological problem. I’ve got a friend in Toronto, who lives in the outskirts of Toronto in a high-rise apartment building, completely air-conditioned. He goes downstairs into his elevator to his air-conditioned garaged, gets into his air conditioned car, drives down the freeway into the basement of an air conditioned commercial building, up into his office.

That building is connected through a massive set of tunnels to huge shopping centers and food marts. He said, ‘David, I don’t have to go outside, for days on end!’ So, who needs nature? We’ve got our own habitat. And, in a city, our highest priority becomes our jobs. We need our jobs to earn money to buy the things that we want. And, so our economy becomes our highest priority and that’s why we elevate economy above ecology and we think that everything’s gotta be done to service the economy. Even though, the economy now is so big, it is undermining the very life support systems of the planet! It’s using air, water and soil as a garbage can. Each of us now in the industrialized world, carries dozens of toxic chemicals dissolved in our bodies- over a pound of plastic dissolved in our bodies. We are the consequence of this industrial growth, because we have elevated the economy above the very things that keep us alive. And this is madness!

CURWOOD: David, at one point in your book, to explain the relentless need for growth in economies, you compare us to bacteria in a test tube. Can you explain that for us?

SUZUKI: Ok, let me give you some background now. We have come to believe that growth is the very definition of progress. You talk to any businessperson or politician and say, ‘How well did you do last year?’ And, within a picosecond, they will talk about growth in the GDP and the economy in profit, jobs or market share. And, anything in a finite world cannot grow forever. We live within the biosphere, that cannot grow- it’s fixed.

And, I use the analogy of the bacteria in the test tube for why it’s suicidal to look for steady endless growth. Anything growing exponentially has a predictable doubling time. I give you a test tube full of food for bacteria- that’s an analogy with the planet- and I put one bacterial cell in and it is us. It’s going to go into exponential growth and divide every minute. So, at time zero, at the beginning, there is one bacterium. One minute, there are two. Two minutes, four. Three minutes, eight. Four minutes, 16. That’s exponential growth.

And at 60 minutes, the test tube is completely packed with bacteria, and there’s no food left. When is the test tube only half full? And the answer of course, is at 59 minutes. So, at 58 minutes it’s 25 percent full, 57 minutes, 12 and a half percent full. At 55 minutes of the 60-minute cycle, it’s three percent full. So, if at 55 minutes, one of the bacteria looks around and says, ‘Hey guys, I’ve been thinking, we’ve got a population problem.’ The other bacteria would say, ‘Jack, what the hell have you been drinking, man? 97 percent of the test tube is empty, and we’ve been around for 55 minutes!’ And, they’d be five minutes away from filling it.

Acclaimed scientist and environmentalist, David Suzuki. (Photo: David Suzuki)

So, the bacteria are no smarter than humans. At 59 minutes they go, ‘Oh my god! Jack was right! What the hell are we going to do, we’ve got one minute left! Well, don’t give any money to those economists, but why don’t you give it to those scientists?’ And, by God, somehow those bacterial scientists in less than a minute, they invent three tests tubes full of food for bacteria. Now, that would be like us discovering three more planet Earths that we could start using immediately. So, they’re saved, right, they’ve quadrupled the amount of food in space. So what happens? Well, at 60 minutes, the first test tube is full. At 61 minutes, the second is full, and at 62 minutes, all four are full. By quadrupling the amount of food in space, you buy two extra minutes. And, how do you add any more air, water, soil or biodiversity to the biosphere. You can’t, it’s fixed! And, every scientist I’ve talked to agrees with me. We’re already past the 59th minute.

CURWOOD: David Suzuki, this is, I think, one of the most powerful images I have heard of, what some people call the environmental crisis, but I think you probably call it the human crisis.

SUZUKI: It’s a human crisis. We’re at the center of it. You know, for years, we environmentalists thought that humans are taking too much stuff out of the environment, putting too much waste back into it. And, for me, I got a huge shift when I began to work with First Nation, aboriginal people in Canada. And, they showed me, there is no environment out there and we are here. We are created by the Earth by the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat. And, the energy in our bodies, it comes from the sun. We are the environment, whatever we do to the environment, we do directly to ourselves.

CURWOOD: One of the most fascinating things in your work, David Suzuki, is the discussion you have of the temperate rainforest and the salmon and its connection to it. I wonder if you can share that with us now.

SUZUKI: That is such a wonderful story. One of the rarest ecosystems on the planet is the temperate rainforest. That’s the very thin strip that extends all the way from Alaska to California pinched between the Pacific Ocean and the coastal mountain range. The salmon are born in these rivers, they go out to sea, and they grow in the oceans and accumulate the nitrogen from the ocean. And then when they come back the bears, wolves and eagles eat these salmon and they poop and pee all over the woods.

It turns out that the salmon are the biggest pulse of nitrogen fertilizer that the forest gets, and the bears are the vectors to carry the nitrogen. They’ll fish for these salmon, once they grab one, they hike off up to150 meters on either side of the river, they eat the salmon- they eat the best part- and they dump the rest of the carcass on the floor of the forest and go back for another one. As soon as they dump the carcass, well, salamanders and slugs and ravens begin to eat it. But the main things are flies that lay their eggs on the carcass. And, in a few days the carcass is a seething mass of maggots eating that nitrogen from the ocean. They drop onto the forest floor, and they pupate over the winter and the spring trillions of flies loaded with nitrogen from the ocean, from the salmon, hatch at the very time that the birds from South America are migrating through the forest on their way to the Arctic nesting grounds. So the salmon come back and they nourish the flies, which feed the birds.

Now, we know the forest, the salmon need the forest. If you clear-cut the forest, the salmon populations plummet or disappear because the salmon need the forest canopy to keep the waters cool. They need the forest to hold the soil so when it rains it doesn’t run in and spoil the spawning gravels. And the forest feeds the baby salmon on their way to the ocean. So we know the salmon needs the forest, now we know the forest needs the salmon. So you see this beautiful system where the ocean is connected through the salmon to the forest, and the birds from South America are connected to the northern hemisphere.

Humans come along, and we go ‘Oh, well uh, gee there’s a lot of salmon here. That’s a Minister of Fishers and Oceans for the fishing fleet. Oh, the trees, well that’s a Minister of Forestry. And the eagles, bears and the wolves, that’s the Minister of the Environment. Gee, the river that’s managed by the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Energy. And, the rocks, the mountains, that’s the department of mining. So, what is a single interconnected system, we come along, fragment into different bureaucracies and try to manage a complete system through this fractured way of looking at the world. And, we will never do it in the right way when we look at it that way.

CURWOOD: So, what’s the solution?

SUZUKI: The solution is: our great advantage, what got us to where we are, is our brain. We invented the idea of a future, we could dream of a future in which we could avoid danger and exploit opportunity. I believe foresight was the critical feature that got us out of the plains of Africa to occupy the entire planet. So, what do have to do? Imagine a future that is free of danger and full of opportunity. So, how about this: how about an America, as Canada was as I was a kid, where you can drink the water out of any lake? Where you can catch a fish and eat it without worrying about chemicals are in it. An America where asthma and cancer rates plummet because we no longer use air, water and soil to dump our toxic chemicals. Let’s imagine a future full of opportunity and promise, and then we have a goal that we can work towards, and we know what direction we want to go in, and everybody will be in it together. This is what we’ve done in Canada- we’ve created a vision for one generation away. And, when I presented this to the business community, to the mayors of Canadian cities, to the faith community- everybody says, ‘Well of course, I would love to have a Canada like that.’ So, suddenly, we’re all together, we’re not fighting. We all agree, that’s the kind of country we would like to achieve. So, anything we do today, we say, ‘Okay, that’s an interesting proposal, but does that get us closer or further away from that target that we’re moving towards?’

CURWOOD: You say, so if Canada can make this a target, so can the United States of America.

SUZUKI: Why not in the United States?

CURWOOD: And, what about in the rest of the world?

SUZUKI: Absolutely. I think these movements are all things that we have to begin right away.

CURWOOD: David Suzuki’s new book is called “The Legacy: An Elder’s Vision for Our Sustainable Future.” Thank you so much David Suzuki.

SUZUKI: Thanks for having me, it’s been fun talking to you.

Related links:

- David Suzuki Foundation website

- Click here for an extended interview with David Suzuki

CURWOOD: And, you can hear more of our interview with David Suzuki online at L-0-E dot org. On the next Living on Earth – at 5 yrs old JC High Eagle had a vision.

O’CALLAHAN: He said, ‘Mom, I heard a voice!’ ‘A voice?’ ‘Yes. It was coming from way up near the sun – it said I was going to have something to do with getting people to the moon!’

CURWOOD: Against great odds that vision came true. “Forged in the stars,” a winter holiday storytelling special - hear it next time on Living on Earth.

Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Ingrid Lobet, Bruce Gellerman, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, Mitra Taj, and Jeff Young, with help from Sarah Calkins, Sammy Sousa, and Emily Guerin. Our interns are Nora Doyle-Burr and Honah Liles. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org, and while you’re online, check out our sister program, Planet Harmony. Planet Harmony welcomes all and pays special attention to stories affecting communities of color. Log on and join the discussion at my planet harmony dot com. And don’t forget to check out our Facebook page, PRI’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth hormones on their cows. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners. The Ford Foundation, The Town Creek Foundation, The Oak Foundation—supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues. The Bill and Melinda Gates foundation, dedicated to the idea that all people deserve the chance at a healthy and productive life. Information at Gates foundation dot org. And Pax World Mutual Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at Pax world dot com. Pax World for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI – Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth