May 21, 2010

Air Date: May 21, 2010

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Cell Phone Use May Take Toll

View the page for this story

Buried deep within a long anticipated study about cell phones is evidence indicating a strong link between mobile phone use and brain cancer. Living on Earth host Steve Curwood talks with Dr. Elizabeth Cardis, director of the Interphone study, about the findings. (05:00)

BP Spill – Investigating Criminal Intent

View the page for this story

In a letter to Attorney General Eric Holder, and Senator Barbara Boxer along with seven other senators, have asked for an investigation into BP’s ability to respond to oil spills. They’re questioning whether corporate officials may have known about previous damage to the blowout preventer. Host Steve Curwood talks with Jonathan Turley from the George Washington University Law School about the potential for criminal investigations. (06:55)

Gulf Oil Damage

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

Researchers and conservationists all along the Gulf Coast are collecting data and bracing themselves for the short and longterm effects of the BP oil spill on critical and sensitive wildlife and ecosystems. Living on Earth’s Jeff Young joined researchers in Louisiana and Texas as they monitored bird habitat and to see just what’s at stake in the region. (13:00)

Sustainable City Gardening

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Gardening season is here again but the urban gardener doesn't need to be confined to growing plants in containers. In Boston, Patti Moreno, the self-proclaimed Garden Girl, grows so much food in her backyard that she opens up a small farmer's market each summer. Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb went to check out a garden that is anything but garden variety. (04:40)

Eau d’ Fragrance Fears

/ Ike Sriskandarajah and Ebony PayneView the page for this story

Smelling nice may have a hidden price. A new report from The Environmental Working Group suggests that a number of unlisted ingredients in scented products can trigger allergies and disrupt hormones. Living on Earth and Planet Harmony’s Ike Sriskandarajah and Ebony Payne ask the fragrance makers and users what’s going on. (06:00)

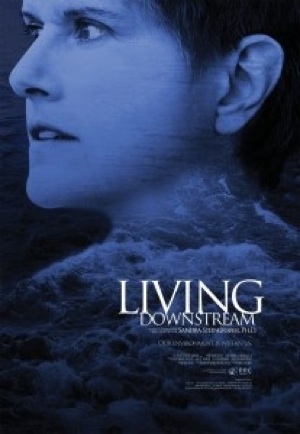

Living Downstream

View the page for this story

Biologist Sandra Steingraber wrote about evidence linking cancer with environmental toxics in her book "Living Downstream.” Now she brings her case to the big screen in a new film of the same name. Host Steve Curwood talks with Steingraber about her efforts to make the environment part of the public health discussion. (10:55)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Green Island in Laguna Madre, Texas is for the birds. The protected rookery is the major breeding grounds for a wide variety of birds.

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Elizabeth Cardis, Jonathan Turley, Sandra Steingraber.

REPORTERS: Jeff Young, Bobby Bascomb, Ebony Payne, Ike Sriskandarajah.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International—this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. As U.S. Senators and others call for criminal investigations into the oil spill disaster, the gusher in the Gulf has citizens and officials fighting the oil – on the boats, in the marshes, and on the beaches.

KENDAL: The oil is going to go somewhere. We know it's in the Gulf at this time and we feel at this time there’s really no area on the Gulf Coast that’s safe from the effects of this current oil spill.

CURWOOD: We report from the front lines in Louisiana and Texas. Plus—they may smell enticing, but those fragrances you splash on your skin may be bad news for your health.

HOULIHAN: There’s a giant loophole in federal law that allows companies to hide compounds, not label them in perfumes, colognes and body sprays.

CURWOOD: What you don’t know might really hurt you—We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. So stick Around!

[Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Cell Phone Use May Take Toll

The use of cell phones has grown exponentially. (Photo compujeramey)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts—this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. This week, a scientific controversy that affects just about all of us. The question: how safe are cell phones?

And now a major study that was supposed to answer that question is open to question itself. The so-called Interphone Study, started a decade ago, when scientists in 13 nations set out to learn if there was a link between cell phone use and brain cancer. At last, the findings of this eagerly anticipated study have been released, and researchers found that…well…here are some of the headlines reporting the results:

FEMALE: “Mobile Phone Study Finds No Solid Link to Brain Tumors”- The Guardian, UK.

MALE: “Heavy Use of Cell Phones may increase Tumor Risk.” Globe and Mail, Canada.

FEMALE: “Mobile Phones are Safe” Die Welt, Germany.

CURWOOD: So if you’re confused, you’re not alone. Consider these contradictory findings: High cell phone usage was linked to a doubling of the risk of deadly brain cancers called gliomas. But some people who never or very rarely used cell phones seemed to have more tumor risk than moderate users. Epidemiologist Elizabeth Cardis headed the Radiation Group, which conducted the Interphone Study.

Elisabeth Cardis (Courtesy of The Center for Research and Environmental Epidemiology)

CARDIS: The study is very complex and the interpretation is not clear. And we have not demonstrated conclusively that there’s a risk, but I think it’s really important to note that that does not mean that there’s no risk. We have a number of elements in the study which suggest that there might actually be a risk, and particularly we have seen an increased risk of glioma, which is one type of malignant brain tumor, in the heaviest users in the study—in particular on the side of the head where the tumor developed and in particular in the temporal lobe which is the part of the brain closest to the ear so closest to where the phone is held, so that’s the part of the brain that has most of the exposure from the phone.

CURWOOD: Indeed, I’m looking at something known as Appendix Two, a table in your study that shows for gliomas is what—twice as likely to have one of these brain tumors if somebody was a heavy user of cell phones over a long period of time with a good 95 percent confidence rating for this finding. Why is there such a confusion about this? Why isn’t this a valid finding?

CARDIS: Well, we don’t know whether the finding is correct. Basically, there are a number of possible biases which are typical with these kinds epidemiological studies, which could have affected the results. And the increased risk could be just something we call recall bias, so we really can’t conclude that there is a risk from our findings because of the potential of bias.

CURWOOD: Why not simply look at their cell phone records?

CARDIS: We’ve tried to do that actually in a smaller scale validation study. We had hoped to be able to do that on many people in the study but, unfortunately, at the time we did the Interphone Study it was very difficult to go back in operators’ records and get long time historical records for the study subjects.

CURWOOD: By the way, the number of minutes per day that somebody used a cell phone that considered a “high” use averaged—what—less than 30 minutes a day?

CARDIS: Yes, that’s correct. I mean, Interphone was basically carried out between 2000 and 2004, depending on the country, and we asked about people’s long-term historical use of mobile phones. We were asking about their use of the late 1980s, early 1990s, at a time when mobile phones were used much less than today. And one of the reasons we are concerned about the results of the study, even though we cannot conclude for sure, is that where we see the increase is in these people—half an hour a day for 10 years was a high use in the participants of that study, but it’s a normal reason or relatively low use today.

The use of cell phones has grown exponentially. (Photo compujeramey)

CURWOOD: You’re using a cell phone right now, as we speak?

CARDIS: (LAUGHS) I am using a cell phone right now, yes.

CURWOOD: How worried are you?

CARDIS: I don’t use a cell phone very much and when I can, I basically try to find ways to reduce my exposure, either using a landline or using the speaker of my phone.

CURWOOD: And do you have any children, Dr. Cardis?

CARDIS: Yes, I have two children.

CURWOOD: How old are they, and are they allowed to use cell phones?

CARDIS: They are eight and 11 years old and they do not have a cell phone. They use it very, very rarely when they have to, but they don’t have a cell phone.

CURWOOD: Now, Dr. Cardis, you’re an epidemiologist, you’re not a journalist, so it’s probably unfair of me to ask you to do my job, but if you had to write the headline for this story, what would it be?

CARDIS: That’s a very good question. What is your headline? In my opinion, and as I said this is a very complex study, and its biases in areas limit the interpretation so we have different people in study groups interpreting the results differently. In my personal opinion, I think we have a number of elements that suggest a possible increased risk among the heaviest users, and because the heaviest users in our study are considered low users today, I think that’s something of concern.

CURWOOD: Epidemiologist Elizabeth Cardis directed the World Health Organization’s Interphone Study. Dr. Cardis spoke to us by cell phone from Barcelona.

[Marc Ribot “Todo El Mundo Es Kitsch” from Ceramic Dog (Tzadik Records 2003)]

Related links:

- The International Agency for Research on Cancer

- International Journal of Epidemiology

- Microwave News

- Center for Research on Environmental Epidemiology

BP Spill – Investigating Criminal Intent

Jonathan Turley is J.B. & Maurice C. Shapiro Professor of Public Interest Law at George Washington University Law School. (Courtesy of Jonathan Turley)

CURWOOD: We turn now to the massive BP Oil Well blowout in the Gulf of Mexico and the question of criminal behavior. At least eight U.S. senators—all Democrats from the Senate Environment and Public works committee are calling for a criminal investigation of the disaster. Jonathan Turley teaches at George Washington University Law School and he says it’s a matter of when—not if—the companies and employees involved will face grand jury probes.

TURLEY: When you have an environmental accident of this size there’s a presumption that criminal investigations will follow. There’s a number of reasons for that: one is the relatively low amount of civil penalties that come with these environmental disasters. Congress, which is so vociferous these days about combating big oil, has spent the last couple of decades doing the bidding of many of these same companies.

The best example of that is the oil pollution act of 1990—that act has perfectly ludicrous penalties cap of 75 million dollars. That’s nothing, I mean, that’s actually less than what these companies would spend on litigation in something like the Exxon spill. So what often happens is that absent criminal prosecution, there’s little hope to get serious penalties against a company like BP or these contractors.

CURWOOD: So the three companies involved here—BP, Transocean, and Halliburton—what’s their criminal record from the past?

TURLEY: Well, BP particularly has had recent problems in terms of environmental accidents and criminal liability. The most obvious was in 2005 in a Texas explosion that was fatal and ultimately cost that company and its subsidiaries around 372 million dollars in penalties.

CURWOOD: What’s the basis of the law to go after these firms on a criminal basis?

TURLEY: The most obvious charge would be criminal negligence, and they will look specifically at the blow out preventor allegation. Whether in fact that device had been damaged previously to the knowledge of corporate officials. The second most likely criminal charge would be false statements, either in government reports or in statements with investigators after the explosion.

With the level of finger pointing we have seen between BP and Transocean and Halliburton, there’s an increased chance that some officials might give false or misleading statements to investigators. Officials often make situations worse by spinning data, or hiding data, or misleading investigators.

Jonathan Turley is J.B. & Maurice C. Shapiro Professor of Public Interest Law at George Washington University Law School. (Courtesy of Jonathan Turley)

CURWOOD: Let’s look specifically at any possible criminality around the failure of the back up system—this blow out protection system. What might be criminal around the failure of this blow out protection system?

TURLEY: Well, we still need to know a lot more but there has been an allegation that the blow out preventor was damaged before this latest explosion. If that’s the case the criminal investigators are going to be looking for knowledge by BP or Transocean or one of the other companies involved.

That’s a critical system needed for the safe operation of the rig. If company officials instructed workers to continue to operate without that system functioning properly, it most certainly can be a criminal violation.

CURWOOD: At this point, who’s in trouble, and how far up the ranks of BP could this go?

TURLEY: Well, what we have to see is the paper trail, particularly connected to the blow out preventor. Who was aware if this device had been previously damaged? Who ordered the continuation of production and operation? Those are the questions federal prosecutors will look at. It is not uncommon to see those types of inquiries go very high in a company. If, for example, the blowout preventor was known to be damaged and an order was given to continue to operate regardless of the dangers, the federal investigators will look at who gave those instructions, but also what policies led to those instructions.

Now what happens then is that the prosecutors will start with the low lying fruit, i.e., if they have someone who’s at risk of a criminal penalty they will hammer them and they will get their own lawyer and that lawyer is likely to ask their client weather they have anyone else to give up. That’s what happens in these cases; if you’ve got somebody who looks dead to rights on a criminal charge their lawyers will tend to look for a deal. That deal usually involves handing over someone higher up in the company.

CURWOOD: What’s the likelihood that people will go to jail over this case?

TURLEY: Well, there’s an expectation of the public that a disaster of this size will result in serious punishment, including jail time. You have various potential defendants here as companies, and each of those companies has literally hundreds of people who were involved on some level with this case.

CURWOOD: What has a bigger impact on companies, civil or criminal cases?

TURLEY: The important thing about criminal penalties is not just that corporate officials can go to jail but that the civil cap on penalties under the oil pollution act of 1990 are no longer relevant. In criminal law you can often get a multiplier, you can actually get more than the actual damage found by the court as part of the penalty. So for BP or these other companies, criminal prosecution could have a devastating impact not just simply in terms of the actual penalties but the impact it will have on their stock.

As for their officials, they are personally accountable under criminal law if there’s evidence they knew of these problems or that they intentionally lied to investigators. If you’re an attorney for one of these companies, these are going to be one of those long nights because you can’t really control what people are saying without being accused of obstruction. So you have a lot of people talking to a lot of investigators and any of those communications can technically become a basis for criminal prosecution if they are evasive or false.

CURWOOD: Jonathan Turley is a professor of law at George Washington University Law School. Thank you so much.

TURLEY: Thank you, it was a great pleasure.

[Bill Frisell “ Procissao” from the Intercontinentals (Nonesuch records 2003)]

CURWOOD: Just ahead—the view from the Gulf coast, and why a city garden needs chickens. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

Related links:

- Senator Boxer’s letter to Attorney General Eric Holder:

- Jonathan Turley’s blog

Gulf Oil Damage

Melanie Driscoll, director of the Audubon’s program in Louisiana, scans Grand Island, Louisiana for birds affected by the oil disaster. Behind her is the orange line of an oil boom in the water. (Photo: Jeff Young)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Recently a reporter with Sky News asked BP CEO Tony Hayward what he thought the oil gushing from his company’s blown out well will do to the Gulf of Mexico.

HAYWARD: I think the environmental impact of this disaster is likely to have been very, very modest. It is impossible to say and we will mount, as part of the aftermath, a very detailed environmental assessment but everything we can see at the moment suggests that the overall environmental impact of this will be very, very modest.

CURWOOD: Well, as much as we might want to think that Mr. Hayward is right many researchers all along the Gulf coast suspect otherwise. They are scrambling to get a handle on the ecological effects of this massive oil spill. And Living on Earth’s Jeff Young has been scrambling along with some of them. His story begins in southern Louisiana.

[SOUNDS OF SURF]

YOUNG: Grand Isle is about as far south as you can get in Louisiana by land—or what’s left of the land, anyway. Erosion and subsidence have melted miles of the surrounding marsh into open water. But this is still crucial bird habitat and an important time for birds—breeding season.

DRISCOLL: There are least terns mating. That would be normal breeding season behavior.

YOUNG: Melanie Driscoll has binoculars pressed to her eyes—as she often does. She directs Audubon’s Louisiana program.

DRISCOLL: They’re just toward the edge of the water, it’s a very quick event—it’s over already.

YOUNG: They’re not big on afterglow, are they?

A White Ibis stands in the Green Island Rookery in Laguna Madre, Texas (Photo: Bart Ballard)

DRISCOLL: [Laughs] Bird copulation is a fairly short-lived event without a lot of ceremony, usually.

YOUNG: The male tern flies back to his mate with a gift—a small fish. In a normal year this would be a happy time and a happy scene for Driscoll, watching resident species take to the nests and thousands of migrants pass through. But this is not a normal year. The long line of bright orange oil booms just offshore reminds us. The dozen or so oil platforms on the horizon remind us. And everything about the terns’ little love scene here now seems loaded with danger—is the oil in the water here? Is it in that fish he just caught?

DRISCOLL: They don’t get any warning. They eat the food, they drink water of the Gulf and they are driven to breed where they’ve bred before, whether that habitat is disturbed or not just affects their success not their drive to breed here.

YOUNG: There are globally important bird areas in these marshes and barrier islands. And some are now taking oil. Driscoll is here to keep tabs on what is likely to be a grim toll. The oil is slowly taking effect just as many birds are most vulnerable. She takes meticulous notes on the sanderlings, turnstones, redknots, brown pelicans. The point is not just to look for oiled or dead birds, but to detect the absence of birds.

DRISCOLL: Because birds will die undiscovered we are less reliant on a body count in this spill because it is so different than eventually a change in abundance, a change in numbers.

A Red Morph in the Green Island Rookery in Laguna Madre, Texas (Photo: Bart Ballard)

YOUNG: So you might not know what’s really going on here until next year?

DRISCOLL: We likely won’t know for a year for some species. Others species many birds, of northern gannets, particularly young, stay out in Gulf for a couple of years until they reach breeding maturity, if those birds are dying it may be three or four years before we notice a change in the nesting population.

YOUNG: It’s so complicated the interaction of things here. As a layperson your impression is well, is there oil on the bird? No? Well, okay! But there’s a lot more to it than that.

DRISCOLL: There’s a saying about ecology that it’s not rocket science, it’s a lot more complicated than that. We’re looking at a system. The birds rely, not just on their feathers insulating them, they rely on food chains that are underwater or in the sand, they rely on protection from predators by being familiar with their surroundings—it’s very complicated.

YOUNG: And it gets more complicated. Several fish stocks in the Gulf were already in serious decline. The mouth of the Mississippi already sees a massive dead zone of low oxygen each year. The land is slipping into the sea. And now comes the oil. Driscoll wonders how much the ecosystem can take.

DRISCOLL We don’t know. We’re playing roulette with these Louisiana marshes. They’re under many, many threats. They’re in a working landscape and that puts them at more risk for oil and gas spills. We don’t know this fragile systems are very productive. There’s a threshold you might have increased productivity before a crash. We’re afraid of the crash. We don’t know what will be the tipping point. The oil makes that tipping point probably closer.

Melanie Driscoll, director of the Audubon’s program in Louisiana, scans Grand Island, Louisiana for birds affected by the oil disaster. Behind her is the orange line of an oil boom in the water. (Photo: Jeff Young)

YOUNG: Driscoll and other scientists and conservationists in the region are settling in for a long haul effort. Stopping the gushing oil in the Gulf may be a race, but understanding the ecological impact is a marathon.

[SOUNDS OF SURF CONTINUE]

YOUNG Somewhere out there just to the southeast is the shifting slick—at times as large as Maryland—and always moving with wind and currents. And underneath? Well, that’s hard to say. Some researchers detected subsurface plumes of oil tens of miles long. But they have questions about just how much oil, its consistency and behavior in the water.

As it turns out, just up the beach on Grand Isle I run into someone who might be able to help answer some of those questions. Hans Thomas is with the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

THOMAS: We were brought out by British Petroleum to operate some oceanographic sampling gear. We have a little underwater robot that can swim all the way to the bottom near where the leak site is and sample water and bring it back to us on the ship.

YOUNG: What would you learn from that?

THOMAS: What we’d learn is twofold. First of all, we’d be able to understand how dispersants are interacting with the oil, and then we’d also be able to understand how the oil is distributing itself in the water column, so that we’d have a better idea of exactly how much oil is coming out is and where it is and where it’s going to go.

And one of the things we’re going to try to do with all this data is put it in more of a comprehensive context of how this oil is going to end up impacting both life at the surface of the ocean and, more importantly, life at the bottom of the ocean—at the benthos—and that’s again going to be very critical to understanding what’s going to be going on in this ecosystem five, ten years from now as this oil finally works its way through.

YOUNG: This sounds like great work but we’re standing here on a beach you’re not out there doing your work, why’s that?

THOMAS: Uh, right now, we’re still in consultation with NOAA and BP as to exactly what they want to study with our systems. And I’m hopeful that we’ll get some work done. We came out here to try to help and we’re anxious to do that.

YOUNG: Other scientists are eager for the kind of data Thomas might provide. They are intensely concerned about the sub surface oil. It’s a sort of wild card element here, with major implications for marine mammals like dolphin and the sperm whales that feed not far from the spill site. For the endangered blue fin tuna now spawning in the Gulf. And for sea turtles nesting on Florida’s coasts, that’s where David Godfrey expects to see the oil’s effects soon.

GODFREY: I personally think it’s almost certain that we will.

YOUNG: Godfrey directs the Caribbean conservation corps. He says now that some oil has entered what’s known as the loop current, that will likely bring it to Florida’s waters just as turtle nestlings emerge.

GODFREY: Very shortly, turtles are going to start hatching in the millions from the coast of Florida. And those hatchlings will make their way into the very currents that’s carrying all this oil and tar. And the little turtles are opportunistic feeders. They will grab anything that’s floating around in those currents, namely tarballs so there have been a lot of studies looking hatchlings gathered up in these currents following previous spills and almost every one of them ends up with tar in their mouths and in their guts.

[SOUNDS OF MOTOR BOAT ENGINE]

YOUNG: Across the gulf from those Florida beaches, on the Texas coast south of Corpus Christi, I hitch a ride with a team of scientists from Texas Tech University. The boat skims across the shallow Laguna Madre—the mother lagoon—one of the world’s few hyper-saline coastal ecosystems. Redfish and mullet break the surface, dolphin arc along. Our destination is Green Island. It’s a rookery, jam packed with shorebirds.

[SOUNDS OF BIRDS IN BACKGROUND]

YOUNG: The birds are just everywhere in the brush here. Another roseate spoonbill just went overhead. This is like Manhattan for shorebirds.

YOUNG: Steps lead to a bird blind just above the mesquite and prickly pear. The island is carefully guarded by David Newstead and his crew at the Coastal Bend bays and estuaries program.

NEWSTEAD: There’s a whole range of pretty much all of the herons and egrets that breed on the coast are here—great egrets, great blue herons, we have little blue herons, snowy egrets, tri-colored herons, reddish egrets—there’s both light and dark morph of reddish egrets. This is probably the most important colony for reddish egrets in the world. Up to between 500 to 1000 pairs breeding here.

YOUNG: The whole island is a collage of long legs and feathers, flashes of pink, blue and brilliant white. For Ron Kendall, this is an example of what’s at stake in the Gulf. He directs the Institute of Environmental and Human Health at Texas Tech.

KENDALL: If oil gets access to these kinds of areas it’s not only difficult to clean it up but it could be devastating for the food source. So, you might not have to directly kill the birds by oil but when you take away food source or the habitat—for instance, the turtle grass flats, the inland flats where all your juvenile fish and shrimp and crabs are, those are the areas you got to protect. It’s why all these birds are here.

YOUNG: Now you’ve got the barrier islands out there and we’re a long way from where the oil is now. Are you really concerned that you’ll see oil here?

KENDALL: Well, we know that we’ve had millions and millions of gallons of oil leaked into the Gulf now and some of it is on the surface. But not it’s not necessarily just what’s on surface; it’s what’s in water column or what’s on the bottom. We’ve got a calm day today, but it’s not necessarily always calm and we’re nearing hurricane season. So, we don’t know yet what that can do to mobilize oil that may be existing in plumes below the surface of the sea offshore. It may then translocate that oil from offshore to onshore.

YOUNG: Kendall and his colleagues are already monitoring water and sediment to establish a data baseline and be ready for the first traces of oil. Kendall is a leading figure in wildlife toxicology—he edits a scientific journal and wrote widely used textbooks. And he’s worked on a lot of oil spills. This one has him worried.

KENDALL: The oil is going to go somewhere. We know it’s in the Gulf. And we feel at this time there’s no area in the Gulf Coast that’s truly safe from the effects of this current oil spill.

YOUNG: Looking around, this is such a just ridiculous display of life. It seems so full of life and so strong and resilient an ecosystem; it’s hard to imagine that it couldn’t bounce back against some insult like some oil?

KENDALL: Well, There’s a delicate balance here. All these birds have evolved to utilize these habitats and this resource. To me, here on Green Island and the Laguna Madre, this is an enormous reflection of what these ecosystems can produce just given a little protection, a little chance. And at the same time they can be destroyed and they can be taken away from us very quickly.

[SOUNDS OF BIRD SQUEAKS]

YOUNG: The Gulf Coast is filled with paradoxes. It’s one of our richest fishing grounds and richest oil fields. It floors you with its abundance and variety then reminds you just how fragile the whole thing can be. It has come back from oil spills before. Now those who study the Gulf will monitor, measure and wait to see if it can do it again. For Living on Earth I’m Jeff Young reporting from the Gulf of Mexico.

[BIRD SOUNDS CONTINUE]

[Gipsy Kings “Salsa De Noche” from Compas (Nonesuch Records 1997)]

Related links:

- NOAA spill information page

- Texas Tech Institute for Environmental and Human Health

- Caribbean Conservation Corps

Sustainable City Gardening

Patti Moreno feeds her chickens scraps from the gardens. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Michele Obama does it. Thousands of New Yorkers do it. And you too can grow a garden – even if you live in the inner city. That’s the message Pati Moreno is pushing. She’s a native New Yorker, but admits her first horticultural attempts were dismal.

MORENO: Starting out I was horrible. I killed everything I ever planted, but my first success was with some fruit trees. I actually grew apples! They were the most delicious thing ever! So, I was like oh my gosh I can actually plant a plant and eat from it too and I just started branching out from there.

CURWOOD: Today Pati Moreno cultivates 30 raised beds in Boston. She produces so many zucchini and tomatoes and greens each summer she opens up a farm stand in front of her home. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb headed to Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood to check out Pati's brand of urban sustainable living.

[CHICKENS]

MORENO: I just want to see if there are any eggs under these ladies over here. No! No eggs, bummer.

[SOUNDS OF CHICKEN COOP]

An 8 by 6 foot greenhouse was converted into a chicken coop. Patti sells extra eggs to her neighbors in her summer farmer’s market. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

MORENO: They start producing eggs actually at 20 weeks, that’s like a few a week. And as they mature- one day.

BASCOMB: For the average person that whatever to have backyard chickens, how feasible is it?

MORENO: It’s so easy. It’s much easier than a dog. You never have to walk them, unless you want to! They are my garden helpers. They scratch and till the soil for me, they eat all the bugs, and then, they fertilize it.

[SOUNDS OF MOVING THROUGH GATE]

MORENO: Let’s go over to my smaller garden. We’re going go get to work a little bit over here.

BASCOMB: Oh, you’re going to put me to work?

MORENO: And we’re going to put you to work.

[SOUNDS OF SHOVEL]

Patti has 30 raised bed gardens for growing a wide variety of vegetables and cuisine types. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

MORENO: This is basically a demonstration garden that I wanted to put together to show what you could do on like an average size backyard. Being Puerto Rican one of the raised beds I plant every year is a Latin Caribbean mixture of beans and peppers and cilantro—all of the things that you would need to make this thing call sufrito, which is like a base flavor for a lot of the food that you would eat in Latin Caribbean culture.

[Johnny Pacheco “Azucar Mami” from Viva Salsa (Charly Records 1991)]

MORENO: I have a four-by-four raised bed that’s two tiers high, and then I have a square-foot grid that I made that fits right into the raised bed and that’s basically going to be our guide as to where we’re planting everything.

[“Mayor G from El Espiritu Jibaro (Sunnyside Records 2007)]

MORENO: We’re going to companion plant. In this whole bed we’re going to be able to make an amazing stir-fry, so we’re going to have to eggplant, a Siamese dragon stir-fry mix, which has tons of different Asian greens in them.

[SOUNDS OF BAGS OF DIRT MOVING]

Patti holds seeds for an Asian stir fry mix. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

MORENO: Arranging different configurations of raised beds is like my hobby. That’s just fun for me, that’s Saturday night—planning raised beds! It’s a party!

[Johnny Pacheco “Azucar Mami” from Viva Salsa (Charly Records 1991)]

ROBERT: Look, Asian greens are nice. It’s nice, it’s spicy, it’s a different taste, but how about some potatoes and some corn and some lettuce?

[Johnny Pacheco “Azucar Mami” from Viva Salsa (Charly Records 1991)]

ROBERT: My name is Robert Patton-Spurill and I’m Patricia’s husband. I want a record of potato. I want to do 800 pounds of potato and I’m trying to do 200 pounds of corn.

BASCOMB: Wait a second, how big is this garden that you’re growing all of this in?

Patti placed an old skylight over a garden bed to create a mini greenhouse. Inside it is the square foot grid she uses to demarcate where to plant her seeds. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

ROBERT: Very small, it’s not big. It’s only four by eight.

MORENO: This part is for his man garden this year.

ROBERT: You know a lot of people grow potatoes in trash barrels, and that’s the coolest thing ever because basically they put the potatoes at the very bottom in like 6 inches of soil, and as it grows up they keep filling in soil around it, and then at the end of the year they dump it out on a tarp, pull all the potatoes out, and they start over again.

Patti and her husband Rob plant potatoes in his “man garden.” (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

And then that one trash can version people have done really gigantic amounts of potato in it.

MORENO: We every year manage to eat so many meals from the garden. You know the supermarket people do not know me.

[“Mayor G from El Espiritu Jibaro (Sunnyside Records 2007)]

MORENO: Urbanites—it’s our responsibility to start being as sustainable as we possibly can because in the very near future, there’s going to be 70 percent of the world’s population that’s going to live in cities.

[“Mayor G from El Espiritu Jibaro (Sunnyside Records 2007)]

MORENO: Anything you grow and then eat is going to be the tastiest thing you’ve ever had, as long as you don’t burn it you’re fine, and it’s a lot of fun.

Patti Moreno feeds her chickens scraps from the gardens. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[“Mayor G from El Espiritu Jibaro (Sunnyside Records 2007)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb prepared that audio portrait of Pati Moreno, and her inspiring garden, and there’s more at our website, l-o-e dot org.

[“Mayor G from El Espiritu Jibaro (Sunnyside Records 2007)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: the heady scent of hidden chemicals in your perfume—that’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for the environmental health desk comes from the Cedar Tree Foundation. Support also comes from the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund for coverage of population and the environment. And from Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is Living On Earth on PRI, Public Radio International.

Related links:

- Patti Moreno’s Website: Garden Girl TV has dozens of how-to videos

- The City Chicken

- The Square Foot Gardening Foundation

- ">Click here for a Garden Girl video on building a raised bed for urban gardening.

Eau d’ Fragrance Fears

Labels on fragrance products don't have to disclose the ingredients in it. (Photo: Mallyhon)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Today, another story from our sister online initiative called Planet Harmony, where all are welcome and the focus is on young people of color. American Eagle 77, J Lo Glow, Calvin Klein’s Eternity—these fragrances are cool these days.

So Ebony Payne and Ike Sriskandarajah from Planet Harmony decided to look into a recent study by an environmental think tank. It found many of these fragrances have “secret” chemicals that could potentially trigger allergies and disrupt hormones. Their report starts with Ebony Payne chatting with some shoppers at a mall in northwest Washington, DC.

PAYNE: Do you use any products with fragrance in it or any perfume?

MAN: Always.

PAYNE: And do you know what ingredients go into making your products?

MAN: Not really. I know there’s alcohol in there. I dunno.

PAYNE: Would you feel more comfortable buying fragrances if manufacturers actually labeled their ingredients like they do on food?

WOMAN: Yeah, that would be good—my daughter, she’s sensitive to a lot of thing, she has eczema, so I always make sure that things are more natural based

Our nose knows what it likes but we don’t know what’s in the bottle. The Campaign for Safe Cosmetics alleges that smelling good can sometimes cause harm. (Courtesy of The Campaign for Safe Cosmetics)

MAN 2: These days yes, because I do not trust big companies anymore

MAN 3: Um, yeah, I mean I’ll feel more comfortable, but again I won’t know what the ingredients are because there are all these long complicated names and you still have to Google them.

PAYNE: What if you were told that the ingredients in your cologne and in your perfume caused sperm damage and may cause an asthma attack. How would you feel about that?

MAN 4: I dunno, now you’re making me think. Maybe I’ll go home and read what they contain.

WOMAN 2: You’re killing me. I would probably have to stop just because I don’t want to do anything knowingly to harm myself

WOMAN 3: I would not use it anymore.

MAN 5: That would be a shocker; I wouldn’t really want to use that.

MAN 6: There are other ways to smell good.

SRISKANDARAJAH: This is Ike Sriskandarajah. As Planet Harmony and Living on Earth’s Ebony found out most people can’t know what’s in their colognes or perfumes. And since fragrance makers won’t disclose their chemical recipes an advocacy group decided to run their own tests.

The campaign for safe cosmetics analyzed a number of popular fragrance brands like Coco Chanel, Calvin Klein, Halle Berry and Jennifer Lopez. Jane Houlihan of the Environmental Working Group helped author the report on fragrance.

HOULIHAN: So we sent these 17 products to the lab, the lab analyzed them for a range of compounds and found, for these fragrances that we tested only about half the chemicals that are in the product are listed on the label that means there’s an awful lot that you can’t know as a consumer when you’re buying these products.

SRISKANDARAJAH: And what people don’t know could be harming them. The lab tests turned up some potentially hazardous ingredients.

HOULIHAN: Together these products contain about 24 different sensitizing chemicals that can cause allergic reactions and a dozen potential hormone disruptors; these are compounds that in very small doses could possibly throw the body’s hormone systems into disarray.

Labels on fragrance products don't have to disclose the ingredients in it. (Photo: Mallyhon)

SRISKANDARAJAH: Jane Houlihan says hormone disruptors—even in low doses—can pose dangers.

HOULIHAN: We also found a chemical called diethyl phthalate hidden in a number of these products that’s a chemical that’s linked to sperm damage in men, birth defects in baby boys—this is preliminary data, not considered definitive, but quite troubling.

SRISKANDARAJAH: When reached for comment, Coty Incorporated, the company that owns three of the brands named in the study, Halle by Halle Berry, J. Lo Glow by J. Lo and Calvin Klein Eternity, directed us to a written statement, read here by an actor:

ACTOR: All of Coty Inc.'s products are safe and meet all regulatory and legal requirements in all countries in which they are sold.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Coco Channel also declined comment but directed us to a release from the Fragrance Materials Association. Here’s our actor again reading part of their response:

ACTOR: The industry has a long and comprehensive safety-testing program for its materials. Materials are also independently assessed for safety.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The Industry also says Congress recently omitted diethyl phthalate from a list of phthalates of concern. So who’s got it right here? We checked with someone who reviewed the Campaign for Safe Cosmetics’ Fragrance Report on her own.

STEINEMANN: I have independent research funding so I have no conflict of interest. I fund my own work through discretionary university research funding.

SRISKANDARAJAH: From the University of Washington, that’s Professor of civil and environmental engineering Anne Steinnman. She’s spent extensive time studying fragrances.

STEINEMANN: Yes I have. I actually have conducted several studies that analyzed the chemicals in widely used fragrance consumer products. And that’s a big part of my research right now.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The Fragrance industry guards recipes as trade secrets but they publish a list of 3000 ingredients on their website. But there’s no way to know which chemicals are in what products. Professor Steinnman says that no matter how they defend the industry’s lack of transparency, the health impacts on its customers are real.

STEINEMANN: I guess the other point is that people are reporting adverse health effects when exposed to these products. So, rather than try to repudiate these complaints by saying well, we tested these products and they’re safe so you must be imagining it. Why not say, well, people are getting sick from it, what’s in these products that’s causing these effects?

SRISKANDARAJAH: Concerns over potentially poisonous potpourri goes way beyond perfume makers. Fragrances are in nearly half of all personal care products—from the arctic blast in deodorant to the lavender passion in soap. But these scenting chemicals are now getting attention on Capitol Hill

HOULIHAN: There are signs that big changes are about to happen.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Again, Jane Houlihan of The Environmental Working Group

HOULIHAN: This is great news because this law, which regulates all industrial chemicals in this country hasn’t been updated for more than three decades. It’s the only major environmental and public health statue that has never been modernized. And it could mean a lot of changes for the cosmetic industry.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Currently there are chemical reform bills working through the House and Senate. For Living on Earth and Planet Harmony, I’m Ike Sriskandarajah.

CURWOOD: Ike Sriskanderajah edits and Ebony Payne reports for our brand new online offering Planet Harmony, which welcomes all, and is designed to have special appeal for young African Americans. Check it out and join the discussion at My Planet Harmony dot com. That's my planet harmony dot com.

[Trombone Shorty “Hurricane Season” from Backatown (Verve 2010)]

Related links:

- Read the "Not So Sexy" Fragrance report here

- Read the Fragrance Materials Association response here

- The Environmental Working Group built a database to check the chemical makeup of 50,000 personal care products

Living Downstream

A farm in Central Illinois, near where Steingraber was raised. (Photo: Benjamin Gervais)

CURWOOD: Recently the journal Pediatrics reported a link between exposure to pesticides and the condition ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. It seems that almost every week we learn some unsettling bit of news about the effects of chemicals in our food, or water, or air, or the products we use.

Environmental chemicals have long been a concern for author and biologist Sandra Steingraber—particularly those linked to cancer. In a new film based on her groundbreaking book of more than a decade ago, Ms. Steingraber explains why her own cancer diagnosis as a young woman left lingering questions about the disease.

CLIP: I’m one of those people who really does come from a family with a lot of cancer in it. I wasn’t the first in my family to be diagnosed. My aunt went on to die of the same kind of bladder cancer that I had. I have uncles with prostate cancer, colon cancer, but the punch line of my story is that I’m adopted.

CURWOOD: Sandra Steingraber’s book, “Living Downstream”, laid out evidence showing links between environmental toxins and cancer rates in her hometown. Now a new edition of the book and the film of the same name expands the evidence of the relationship between our health and our environment. Sandra Steingraber, welcome to Living on Earth.

STEINGRABER: Thanks Steve.

CURWOOD: Where did you grow up and tell me why you relate the cancer you developed as a young adult to the environment in which you were raised?

STEINGRABER: I grew up right in the middle of the middlest state in America, the second of the three “I” states. Illinois is both and industrial state—we have 30 different industries along the Illinois River valley, and indeed I could look out my back door and see all the smoke stacks of industry, but I could look out the front door and see the farm fields of agriculture—so it’s also a very agricultural state.

An irrigation canal on a farm in Illinois. (Photo: P. Marco Veltri)

And as a young biologist I knew that families have more in common than just chromosomes—that we share an environment. I used some of my background in biology to be able to read the medical literature, and I learned that my particular cancer—bladder cancer—is considered a kind of quintessential environmental cancer.

We actually know more about the environmental contributions to that disease than many others. And so, I was really interested not just in my own cancer, but the cancer rate of the whole area because I’m only a sample size of one. So, yeah, there are it turns out are bladder carcinogens that periodically turn up in my hometown drinking water wells.

CURWOOD: For example?

STEINGRABER: Well, perchloroethylene is one. That’s a solvent that’s used to dry clean clothes, it’s also used in machine shops, which is probably in my hometown how it found its way into the drinking water wells. Trihalomethanes are another group of chemicals that are actually created when we chlorinate water. So I’ve never actually claimed that drinking water with these suspected bladder carcinogens in it as a child is what gave me bladder cancer.

A farm in Central Illinois, near where Steingraber was raised. (Photo: Benjamin Gervais)

But what I do say, from a human rights point of view, when these chemicals are allowed free access to an environment and trespass their way into our bodies, somebody’s going to get cancer. And that’s the problem.

CURWOOD: What about this gap between what’s known about cancer and the environment and what’s communicated and the way people behave about it? Why does this gap persist?

STEINGRABER: I think there are probably multiple reasons for it. When you go into the doctor’s office you always fill out questionnaires about your family, medical history, and there are no questions that ask you about, you know, where is your water supply compared to the toxic waste landfill? What are you exposed to in your occupation?

We come to believe the source of cancer must lie within the DNA machinery of ourselves. I think that we spent a lot of time in the 1990s searching for cancer genes, but the field of study now called epigenetics reveals that in fact there is another layer of instructions on top of our genome—called the epigenome—to mediate environmental messages streaming in from the outside world.

Sandra Steingraber near her home in Western New York. (Photo: Benjamin Gervais)

And so the new thinking now within the scientific community about the way genes and environment interact is more like a piano with our genes as the keyboard, if you will, and the environment as the hands of the pianist. You could play Bach or you could play improvisational jazz—it’s the same keyboard, it’s the same DNA but the environmental messages have changed. And so really we need to see cancer as the result of an interaction between genes and the environment.

CURWOOD: At one point you go back to where you grew up in Illinois and you have an interesting conversation with your cousin who’s a farmer. Let’s listen to some of that from your movie, “Living Downstream”:

MOVIE CLIP: We will use a little bit of atrazine usually in the spring, and it’d be nice to not have to use any. It’s expensive. But in production—ag, today—it’s pretty difficult not to. We try very hard to pick our places we use it; we want to keep it out of the water sources. You know, we stay hundreds of feet from any open creeks or surface drains, wells, things like that.

CURWOOD: Your cousin is using atrazine, which is banned actually in the country where the company that makes it is headquartered—Switzerland, much of Europe it is banned—and yet scientists here in the U.S. say there’s not enough damning evidence. First, before I ask you about your cousin, how much evidence does it take to ban a chemical?

STEINGRABER: I don’t think there’s one answer to that. The filmmaker Chanda Chevannes I think made a very wise decision to choose two chemicals to stand in for the hundreds that I kind of review in “Living Downstream”. Atrazine being one and PCBs being another.

And I think it’s a study in contrast; PCBs are one of the handful of chemicals we abolished in the 1970s on the basis of less evidence than we have now for atrazine, and that turns out to have been a very good decision because new research keeps showing us how strong the link is between PCBs and certain kinds of cancer.

And here’s atrazine—the Europeans banned it based on their belief that it’s an inherently unmanageable chemical because it dissolves in rain, it runs into the water, it evaporates finds its way into fog and snowflakes and raindrops. So here’s my cousin, John, one of the most caring people I know, and yet, like so many other farmers he uses a chemical that is one of the most common chemical contaminates of drinking water. I’m sure he is being extremely careful, but the Europeans have decided that no one can be careful enough with atrazine, it’s like opening Pandora’s box, it’s just unmanageable.

And yet, we have the same data available to us, and we reach a different conclusion.

Steingraber on a bank of the Illinois River. (Photo: Benjamin Gervais)

CURWOOD: It took you, what, four years to make this film you said. And in the course of making it you have a test that revealed some abnormal cells in your own body?

STEINGRABER: I did. I took the camera crew in with me to one of my cystoscopic check ups, in so doing I thought, ‘Well, I’ll pull back the curtain of privacy around this exam, which is so common and familiar to me, but probably most people don’t have a visual image of it,’ and it’s an excellent tool of early detection; it saves lives. It should be me who brings a camera crew into this room, then I got this unexpected result back from that particular exam.

The thing that cancer patients usually do when a test comes back ambiguous is simply pull the curtains of silence around yourself and keep your own counsel. But it’s a kind of high wire act because one wrong word, you know, somebody says something a little too reassuring or they express a little too much worry, it knocks me off the high wire. High wire being I have to be vigilant, I have to advocate for myself, I’m going to need a second opinion, I’m going to need to do some research, but I’m not going to panic, I’m going to hope for the best.

So I’m seeking to make sure that we look as hard as we can for something that I don’t want to find. That’s a very hard psychic place to be and usually you want to have a lot of privacy around you, but we’re in the middle of making a film. And so I knew that I was going to have to talk about these results within the real time of the film and so we did.

Author and ecologist Sandra Steingraber. (Photo: Benjamin Gervais)

CURWOOD: Is there a parallel between this personal uncertainty and that of scientists who are looking, say, for the hard proof about the danger of chemicals who get an ambiguous result that could portend something?

STEINGRABER: So that’s an interesting parallel, actually, I think certainly based on the result of any one study even if it’s statistically significant, we can’t conclude much, and so we’re always in the scientific community looking across in different fields of study—veterinary science, epidemiology, lab bench work—to see whether there’s a kind of state of the evidence that’s beginning to emerge. And the question of our age is, at what time do you decide you have enough data to take action and do something differently?

CURWOOD: What have you done to take action amidst this uncertainty?

STEINGRABER: I’m really interested in taking an upstream approach, a public health approach, to these issues. I’m not interested, for example, in trying to have my children live inside some kind of non-toxic bubble. Moreover, there are many problems that we face that there are no individual solutions for.

Living Downstream Movie Poster (Courtesy of: The People’s Picture Company)

Most likely my bladder cancer came through an exposure in drinking water. Well, it turns out that most of our exposure to carcinogens in drinking water doesn’t actually come from drinking the water—it comes from bathing and showering. So you can drink all the water from France or Fiji that you want in your bottles, but every time you step in the shower you’re having a very intimate relationship with your public drinking water supply.

So you can’t opt out of the food chain or the water cycle. You know what is in the air, the water and the food rearranges itself and becomes our blood and our flesh and our exhaled breath and our urine. If we don’t want these chemicals in our bodies we can’t have them in the environment.

CURWOOD: Sandra Steingraber is author of “Living Downstream” and the principle player in a film of the same name. Thank you so much.

STEINGRABER: Thank you, Steve.

Related link:

Sandra Steingraber’s website

[SOUNDS OF BIRD SQUEAKS]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week in the green . . . Green Island, that is, in the south of Texas.

[BIRD SOUNDS CONTINUE]

CURWOOD: This tiny island in Laguna Madre, Texas is a protected rookery and home to more than 400 species of birds, including white ibis, black crowned night herons, as well as great blues, reddish egrets, and roseate spoonbills. Living on Earth’s Jeff Young joined Audubon scientists in this avian haven as they prepare for possible impact from the Gulf oil spill. He sent us these sounds.

[SOUNDS OF CLICKS, CHIRPS, SQUEAKS, AND SONGS OF BIRDS]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, Mitra Taj and Jeff Young, with help from Sarah Calkins, and Sammy Sousa. Our interns are Emily Guerin and Bridget Macdonald. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE dot org. And check out our new Facebook page – PRI’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield Farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth hormones on their cows, details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from you our listeners, the Ford Foundation, the Town Creek Foundation, The Oak Foundation supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues. And Pax World Mutual Funds integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at Pax World dot com. Pax World for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth