June 18, 2010

Air Date: June 18, 2010

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The White House Battle for a Climate Message

View the page for this story

Many environmentalists were surprised when President Obama's primetime speech failed to include a definitive message on climate change. Host Jeff Young talks with Eric Pooley, author of the new book The Climate War, about how differing opinions in the White House cabinet may be behind this lack of leadership on climate change. (06:00)

Let the River Work

View the page for this story

The Mississippi River could be a crucial tool in keeping oil out of the sensitive Louisiana marshes. The river has already protected certain areas from oil, and Paul Kemp, a coastal scientist with the National Audubon Society, wants to increase this natural defense. Kemp sent a proposal to the EPA asking them to divert more water from a dam near Natchez, Mississippi, and he tells host Jeff Young how the increased water flow could hold more oil offshore. (06:00)

As If Danger Weren’t Enough

View the page for this story

Scientists are racing against time to help save marine birds and other wildlife affected by the oil. National Wildlife Federation naturalist David Mizejewski describes the pelicans and turtles he’s seen in the Gulf. And, the Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle feeds and nests right in the path of the Gulf oil slick. So dependent on this stretch of coast for survival, this endangered sea turtle is particularly vulnerable to the effects of the spill. Host Jeff Young talks with Pat Burchfield, a scientist at Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville, Texas, who has studied the turtle for nearly four decades. (07:05)

The Ixtoc Precedent

View the page for this story

The Deepwater Horizon incident isn’t the first major oil spill to hit the Gulf of Mexico. In 1979 the Ixtoc well blew out, gushing nearly 3.3 million barrels of oil into the shallow waters of the Gulf. Host Jeff Young asks Professor Wes Tunnell of Texas A&M’s Gulf of Mexico Studies program, how the Gulf responded to that spill and how it might respond to this one. (06:00)

Serious Money for Indonesian Forests

/ Mitra TajView the page for this story

Indonesia, one of the world's biggest emitters of greenhouse gases, has partnered with Norway to protect its forest carbon. In exchange for one billion dollars over the next five years, Indonesia has promised to keep its powerful oil palm and pulpwood companies from clearing forest for two years. Living on Earth's Mitra Taj reports on the big deal and some of the big questions it raises. (04:50)

Heated Debate over Heating Milk

/ Jessica Ilyse KurnView the page for this story

Across the U.S. many state governments are taking up the debate about raw or unpasteurized milk. Living on Earth’s Jessica Ilyse Smith reports that while some people claim that raw milk can carry harmful bacteria, making it a threat to public safety, others say just the opposite - that unpasteurized milk can have positive health benefits and a better taste to boot. (06:25)

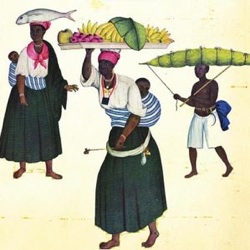

Food That Reaches Back through Slavery

/ Ike SriskandarajahView the page for this story

African Americans celebrate their ancestors’ emancipation on June 19th, a holiday which became known as Juneteenth. On that day, families gather at picnics and cookouts across the South. The passage from Africa isn’t a common topic of conversation at these parties. But even though it isn’t on people’s minds, it is in their stomachs. Living on Earth and Planet Harmony’s Ike Sriskandarajah digs into the green foodways of the Black Atlantic. (06:45)

Natural Poetry

View the page for this story

Living on Earth has been occasionally featuring poetry. Today, Ross Gay waxes poetic about beekeeping. (02:30)

Earth Ear

View the page for this story

To everything there is a season – this week it’s terns, terns, terns. ()

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Jeff Young

GUESTS: Eric Pooley, Paul Kemp, John Lopez, Rodney Echelard, David Mizejewski, Pat Burchfield, Wes Tunnell, Salman al-Farisi, erik Solheim, Fred Stolle, Edgar Pleese, Dennis walsh, Abby Rockefeller, Judith Carney, Isabel Mables, David Gumpert, Michael Twitty, Ross Gay

REPORTER: Mitra Taj, Jessica Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah

[NEWS BREAK MUSIC]: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)

[THEME]

YOUNG: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. The clash over climate change within the White House…Even in the wake of the Gulf oil disaster, not all the president’s men agree on energy policy.

POOLEY: There’s a battle in the White House, the so-called green cabinet they understand the need to transition to clean energy. Then there are political people, they don’t think that the president should waste political capital on a damaging fight that he’s probably not going to win anyway.

YOUNG: Also using Old Man River to push back the oil slick. And – the battle over raw milk…

MABLES: When the food is pasteurized, it kills off most of the bacteria but also actually increases the shelf life of milk, too.

ROCKEFELLER: Bacteria are not our problem; bad farming practices are our problem.

YOUNG: No more crying over spilt milk. We’ll have those stories and poetry this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

The White House Battle for a Climate Message

YOUNG: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios in Somerville MA,

this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. For weeks now, President Obama has talked about the oil disaster in the Gulf as a glaring example of why we need cleaner energy. But there are growing doubts about whether that talk will be followed by action. In his first speech from the Oval office the Pres described an ambitious move away from fossil fuel.

OBAMA: The tragedy unfolding on our coast is the most painful and powerful reminder yet that the time to embrace a clean energy future is now. Now is the moment for this generation to embark on a national mission to unleash America’s innovation and seize control of our own destiny.

YOUNG: However, the president’s speech got a tepid response, and on Capitol Hill, Democrats are openly sparring over energy legislation the senate will consider this summer. Veteran political reporter Eric Pooley’s new book gives a fascinating glimpse into the sharp divisions within the White House. It’s called “The Climate War: True Believers, Power Brokers and the Fight to Save the Earth.” Eric Pooley, welcome to Living on Earth.

POOLEY: Jeff, thanks for having me.

YOUNG: Well, first off the president talked a lot about the need to get away from fossil fuels, which I think is kind of a remarkable thing for a president to do from the Oval Office. However, in that speech, the words “climate change,” “greenhouse gasses,” “global warming,” never passed the president’s lips. What does that tell us?

POOLEY: Well I agree and I think you would need a decoder ring to know exactly what President Obama wanted the Congress to do on clean energy and that’s a shame. I mean it was a bit of a surprise because for 18 months now the fondest hope of the environmental community has been for the president to deliver an oval office address in prime time in which he made the case for accelerating the transition to clean energy, and when the moment comes, Obama does not wholly deliver.

YOUNG: Why do you think the president did not seize that opportunity to talk about what he earlier said was a high-profile item for him, addressing climate change?

Senior White House advisor David Axelrod (Wikipedia Creative Commons)

POOLEY: There’s a battle in the White House for the message here. There are the so-called “Green Cabinet” lead by Carol Browner, the climate and energy advisor, Steven Chu, the energy secretary. They understand the need to transition to clean energy and they’re trying to get Obama to push it as hard as possible.

Then there are political people led by Rahm Emanuel, the chief of staff, and David Axelrod, the chief strategist, who think this is bad politics, that anything that smacks of a tax is dead on arrival because we’re so close to an election. They don’t think the president should waste political capital on a damaging fight that he’s probably not going to win anyway.

The tragedy here is that it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy when the White House chief of staff, the leading political strategist in the White House decide that it can’t be done, then indeed it probably can’t be done because the votes are not there now in the United States Senate, but they won’t be there unless we get serious presidential leadership on this issue.

John Holdren is the President´s science advisor. (Wikipedia Creative Commons)

YOUNG: And I guess the major question now is whether there’s going to be a push to have Congress include some meaningful cap on carbon emissions, or, whether they’re just going to go ahead with what’s called an “energy-only bill,” and address other energy issues, but not the cap on carbon. Last week, we had an interview with the president’s science advisor John Holdren and here’s what he told us about that:

HOLDREN: The president thinks it’s important and his advisors, including me, think it’s important, first of all, to keep energy and climate change together in the legislation. He said again, very plainly, that any legislation that does not succeed in putting a price on emissions of greenhouse gasses is inadequate.

YOUNG: Eric Pooley, to what degree is science advisor John Holdren speaking for the president here?

POOLEY: Well the president had an opportunity to speak for the president in the Oval Office and he did not mention putting a price on carbon. I dearly hope John Holdren is right, and we’ll see if that’s what the president is willing to fight for.

President Obama with Rahm Emanuel, Carol Browner, Phil Schiliro and Larry Summers. (Photo: Pete Souza)

Here’s the funny thing: after the horrible oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico began to engulf the Obama administration, the president was forced to begin talking about clean energy as a way of really changing the subject from oil spill to climate and energy bill and in a speech in Pittsburgh he came with his most forceful language, perhaps ever, certainly in many, many months on the need to limit the amount of carbon pollution and put a price on carbon pollution. The disappointment in the Oval Office speech was that that language was missing.

YOUNG: You know, the president has been pointing to the Gulf spill as a reason to advance clean energy legislation. But you’ve written, “it is a cruel irony that the epic disaster in the Gulf, a wake-up call to the need to reduce our dependence on oil, makes it harder to pass a bill that would help us to do so.”

POOLEY: Well that’s right, and it is a cruel irony. Let me explain why it’s harder. What Obama wants to push, and what the bill in the senate also tries to do, is to create a grand bargain, which, in exchange for a cap on carbon emissions, gives senators things that they want, from expanded nuclear power to expanded off-shore drilling. Of course, the oil spill puts that off the table. So there are a number of oil state senators who are unlikely to embrace a serious energy bill because it now will not contain expanded off-shore drilling because that seems certainly off the table, at least for the near term.

Eric Pooley is author of “The Climate War.” (www.ericpooley.com)

YOUNG: You’ve covered the White House under different presidents for long enough to have a pretty good feel for the issues and the moments that will define a presidency. Does this moment that we’re going through right now have that feel?

POOLEY: Well I think that politics is all about timing, and that the time for Obama to act really was 2009, that the window was beginning to slam shut and now it’s really more about whether Obama can pry the window open again. I hope very much he can. By all accounts the president gets this and understands why this is important. He’s the best communicator we’ve got and he makes the case extremely well when he chooses to. He’s been making the argument based solely on the need to transition off of fossil fuels, and the fact that we’re losing the clean energy race to China and leaving out the most important issue of all, which is potentially catastrophic climate change.

And, the tragedy here Jeff is that we know what to do. We have the policy tools at our disposal. But we haven’t had the political will to do it. But again it’s not too late. The discussions are on-going; the president needs only to lead.

YOUNG: The book is called, “The Climate War: True believers, Power Brokers and the Fight to Save the Earth.” Eric Pooley, thanks so much.

POOLEY: Hey thanks for having me today I enjoyed it.

YOUNG: There’s a longer version of this interview at our website: loe.org.

Related links:

- Click here to listen to an extended interview with Eric Pooley

- Steve Curwood´s recent interview with science advisor John Holdren

- Eric Pooley´s website

- President Obama´s Oval Office Address on BP Oil Spill and Energy

- President Obama´s remarks on energy at Carnegie Mellon University

Let the River Work

The Old River complex controls flow on the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers. Paul Kemp would like more water to reach the Gulf. (Army Corps of Engineers)

YOUNG: Meanwhile, in Louisiana, the fight to keep oil out of the marshes is getting desperate. Governor Bobby Jindal won approval for six berms of dredged sand to block incoming oil. But a number of coastal scientists doubt the sand berms will work, and they warn that changing the water flow could increase harm from erosion.

That debate set geologist Paul Kemp to thinking about other solutions. Dr. Kemp is a coastal restoration expert and Vice President of Audubon’s Louisiana Coastal Initiative. He wants to enlist the mighty Mississippi in the fight against the oil.

KEMP: It did occur to me that perhaps a better tool is out there, that is more at hand, more of a natural solution, and that’s when I came up with idea of just trying to put as much of the river out there as we could. I noticed that we had a situation in which there was a fresh water head on the marshes and this was actually limiting the intrusion of the oil into the interior of these systems. And so, it occurred to me that the most important thing we needed to do was at least try and sustain the flow of the river out there while we’ve got this oil continuing to spew into the Gulf.

Mississippi River water diverted into Breton Sound marsh in La. Under Paul Kemp’s proposal more water would flow through diversions like this to help keep oily water out of marshes. (Photo: John Lopez)

YOUNG: And we can do that, because, we have a sort of spigot on the Mississippi called the ‘old river control’ up river from you that splits the river and sends a lot of it one way instead of the other way. What’s your idea there, what do you want to see done with that?

KEMP: Well right now it’s on autopilot. That is, every day out of the year it’s maintained at what we call a 70-30 split, that is 70 percent of the goes down the main stem past New Orleans and 30 percent goes to a mouth 150 miles to west of the bird split. What I’m talking about is trying to shift more of that flow back over to the main stem so it would be more like 80-20.

And of course that then becomes the source for water going through diversion structures, and out the passes at the mouth of the river, and that’s what’s keeping the oil out of those bays, out of those marshes.

The Old River complex controls flow on the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers. Paul Kemp would like more water to reach the Gulf. (Army Corps of Engineers)

YOUNG: So your idea essentially is just a bigger pulse of water going down the Mississippi to push back against the incoming oil.

KEMP: Yeah, that was the start of it and then it occurred to me we have a lot of water stored behind dams in the tributaries that could be sent our way to try and sustain a higher discharge while we’ve got this oil threatening the coast.

YOUNG: I guess it’s flow of river versus flow of oil. If…

KEMP: Well and the oil comes in with the tides, so you need a force that will oppose the incoming tide and that’s provided by the river, there’s really no other comparable force out there.

[RIVER SOUNDS]

YOUNG: I got a sense of the force of the river on a trip with coastal scientist John Lopez with the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation. Lopez showed me a diversion structure built into the banks of the Mississippi near its mouth in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. When the river’s high the diversion carries two hundred cubic feet per second of Mississippi river water out into the surrounding marsh, pushing back against incoming oil.

LOPEZ: I think that it has that potential. The oil, to a large degree, is carried by currents. If you have an incoming flow that is reversed by having this freshwater flow into it, yeah, that could definitely stop it.

YOUNG: Fisherman Rodney Echelard, of Pointe á la Hache, thinks that flow of river water is what’s keeping him in business, while other fishing grounds have been closed down because of the oil.

ECHELARD: Yeah, yeah, thanks for the river, thanks for river. Y’know with the flow of the river our side we able to fish- but god knows how long that lasts. ‘Cause once the river crests, it’s coming back.

Oyster boats in Bohemia, La. Fishermen say the river’s strong flow is keeping them in business. (Photo: Jeff Young)

YOUNG: Audubon’s Paul Kemp thinks keeping the river flowing high can keep more fishermen in business and keep oil out of the marshes.

KEMP: All I'm asking for is a national plan to deal with this national emergency, and that means putting all the water control assets in the Mississippi Valley to use to prevent further damage to our coastal wetlands.

YOUNG: How much time do you think it would buy for the coast, how much could it do to keep the oil at bay?

KEMP: Well, one of the things we don’t know is how long we’re going to be continuing to endure this nightmare. We don’t know how long before there’s some kind of resolution or stopping of the flow, so, everything we do is trying to buy time, basically, with the hope that at some point the flow will be staunched. If we could just avoid a major oiling of the marsh, then we will have done a lot of good I think.

YOUNG: Dr. Paul Kemp is a coastal scientist for the National Audubon Society, thank you very much.

KEMP: Thank you, it was a pleasure.

Related links:

- A map of the Mississippi Delta Region. (Be sure to check out the satellite version of the map.)

- National Audubon Society’s press release

[MUSIC]: Marco Benevento “Record Book” from Invisible Baby (Hyena Records 2008).

YOUNG: Just ahead, imperiled Gulf wildlife and some hopeful pointers from the past. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

[CUT AWAY MUSIC]: Booker T And The MG’s : “Can’t Sit Down” from Green Onions (Atlantic Records reissue 2004).

As If Danger Weren’t Enough

Nesting Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle (National Park Service)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young. On the Gulf Coast, the race is on to save oil-coated wildlife…

[FANS, BIRD SPLASHING]

YOUNG: The trained specialists at the seabird rehabilitation center in Fort Jackson, Louisiana, have cleaned oil from hundreds of brown pelicans so far. The Brown Pelican just came off the federal list of threatened species last year. Living on Earth’s Amanda Martinez took a tour with naturalist David Mizejewski of the National Wildlife Federation.

MIZEJEWSKI : Yeah, this is pretty tough to look at…these pelicans here are heavily oiled. Their whole bodies are a rusty reddy, nasty looking color…they’ve clearly been oiled head to toe. And the pelican’s natural reaction when it gets oil on its feathers, and this is true of most birds, is that they try to clean it off.

It’s imperative to keep their feathers in good condition because if they are not, they can’t fly. They lose their ability to regulate their temperature-the feathers provide insulation. They provide buoyancy in the water and for an animal like a pelican- they swim on the surface of the water.

So, if their feathers aren’t in good condition, they basically can’t survive. And, so, what they try to do is clean that off with their beaks, and in the process, not only does the oil not come off because it’s so viscous, but they wind up ingesting a lot of that oil- and when they do that, they get poisoned. So, these birds are polluted on the outside but they’re also polluted on the inside.

YOUNG: Reports from out on the water are equally discouraging. Government scientists found the carcass of an endangered sperm whale floating about 80 miles south of the Deepwater Horizon spill site. Further tests will determine what killed the whale. And the Wildlife Federation’s Mizejewski says people are also finding threatened and endangered sea turtles in the oil.

Nesting Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle. (National Park Service)

YOUNG: The Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle is of special concern. It’s critically endangered and nests only on a few beaches in the Gulf. Scientists like Pat Burchfield fear the timing of the spill, coming just as nestlings emerge, could spell trouble. Burchfield directs the Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville, Texas, and leads the US arm of the bi-national Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle Recovery Program. He’s studied the turtle for 38 years.

BURCHFIELD: It’s the smallest of the sea turtles. If an adult takes their arms and makes a circle that’s about the size of a Kemp’s Ridley turtle. And it has a very hawk-like, or parrot-like face, their appendages are adapted into flippers, so they’re very awkward on land, have a difficult time traversing the sandy beach. They have no reverse gear, they can’t turn around and go backwards. If they get up against a piece of driftwood, that’s where it ends.

YOUNG: So what’s your concern now, with the oil that’s out there in the Gulf now, how do you think that might affect the turtles?

BURCHFIELD: The hatchling turtles, after anywhere of a 42-62 day incubation time, make their way to the surface of the sand. And, once they’re ready to go, it’s like someone fired a starter gun. All the babies go into this frenzied behavior and crawl across the sand and out into the waiting surf. They have no real lung capacity when they first start out, but after they get roughly two miles offshore they can stay down for about three minutes and they’re swimming due east into the Gulf of Mexico.

And we suppose that these things are caught up in the Gulf current and they spend the next two or three years floating among sargassum and feeding on the small organisms that live among the sargassum weed. And that also is going to pick up oil and if you look on a map and watch where the Gulf loop current goes, it’s going to go up near shore waters, Texas, Louisiana, towards the mouth of the Mississippi. And that’s going to take those babies into harm’s way.

YOUNG: So these little turtles are basically traveling the same highway, if you will, that the oil is in the Gulf.

BURCHFIELD: Exactly.

YOUNG: So how might the turtles encounter the oil and be bothered by it?

BURCHFIELD: Well, they have to come to the surface to breathe- they’re reptiles and they’re air breathers. So they come up in the midst of it. And the fact that they’re already getting oiled turtles tells us that they’re clearly not able to avoid it, they don’t know to avoid it, they’re in it.

YOUNG: What do you make of the reports of stranded Kemp’s Ridley turtles that we know of, showing up dead on the northern Gulf coast so far. Are those numbers that cause you concern?

BURCHFIELD: The numbers of turtles, Kemp’s Ridley’s this year, are about three times normal for this time of year, and the first turtles that came in apparently did not have visible oil on them. But, at the same time, the percentage of stranding is way up and the government is waiting on results from various laboratories to try and confirm what, perhaps, caused the mortality in these turtles.

YOUNG: And I guess the Kemp’s Ridley was slowly making some progress towards recover, wasn’t it?

BURCHFIELD: We were increasing numbers in the past years, anywhere from 12-15% a year, and last year in Mexico we had over 21,000 nests and released over a million hatchlings and we’re anticipating those same numbers this year, or perhaps an increase.

YOUNG: Did it seem like there was some light at the end of the tunnel for Kemp’s Ridley?

BURCHFIELD: Yeah, it looked like we were on our way towards recovery.

YOUNG: And now?

Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle hatchling. (National Park Service)

BURCHFIELD: Your guess is as good as ours. We’re just trying to hope for the best, but with the waters in the Gulf of Mexico being a little bit on the warm side, that’s an invitation for tropical storms and hurricanes and if we get a hurricane in the Gulf, all bets are off as to where the oil goes.

Kemp’s Ridley is kind of a unique situation because every life phase of this species is in some level of jeopardy. We’re trying to make some contingency plans but that’s where we are. And it’s just kind of sad when you think that they have managed to withstand everything up to now that nature and now man has thrown at them. But maybe this might be the final chime on the bell. I don’t know but we’re going to try and do everything that we can, I can promise you that.

YOUNG: Dr. Pat Burchfield is a scientist at the Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville, Texas. Thank you very much.

BURCHFIELD: No, thank you.

Related links:

- Brown pelican primer

- Blog for the Fort Jackson Bird Rehabilitation Center

- NOAA oil spill incident response page has the latest wildlife impact reports and forecasts for the oil’s spread

- FWS fact sheet on Kemp’s Ridley turtles

- Park Service June update on the impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on the Kemp’s Ridley sea turtles

The Ixtoc Precedent

Ixtoc 1 oil well blowout in Bay of Campeche, 1979. Oil on water. (NOAA)

YOUNG: Well it’s not the first time the Kemp’s Ridley and other sensitive wildlife in the Gulf have faced a big oil spill. In fact, the biggest accidental oil spill of all time nearly smothered the Kemp’s Ridley’s main nesting beach. That spill from a Mexican oil rig called the Ixtoc One started 31 years ago this month. The gusher flowed for 10 months, pumping some 140 million gallons of oil into the southern Gulf. Wes Tunnell, Associate Director of the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M was one of the few scientists to closely study the ecological impact of the Ixtoc spill. And his work gives those watching the current disaster in the Gulf a rare ray of hope. Dr. Tunnell welcome to Living on Earth!

TUNNELL: Thank you Jeff it’s good to be here.

YOUNG: Well now tell me what happened with this oil rig Ixtoc back in June 1979.

TUNNELL: We got word that there had been this blowout of the well, it’s about 50 miles north of the island and city of Ciudad del Carmen in the southern Gulf of Mexico. And knowing the currents we thought it wouldn’t be too long, probably a couple of months, before it would reach the Texas coast. And sure enough, actually two months to the day, the oil started showing up down around the Rio Grand at the very southern border of Texas and Mexico. And then over the next couple weeks it coated the entire shoreline of the south Texas beach area for about 170 miles.

YOUNG: So what did you do when it became apparent that this was a big spill heading for shore?

TUNNELL: So, we went out before it got here with my graduate students and took samples across the beach so we would have samples to know what was living there before the spill got here.

YOUNG: So you had your baseline against which to compare what the oil was doing to those organisms.

TUNNELL: Yes, that’s exactly true. It’s amazing the number of small creatures, mainly little invertebrates that live in the sand out there. Most people aren’t aware as they’re walking on the beach that there’s literally thousands of different kinds of little worms, crustaceans, little shrimp-like creatures down below their feet. And those are all a lower part of the food chain and very important to that area. There were reductions in the numbers of individuals in the inter-tidal zone to as much as 80 percent, and so we were greatly concerned about that.

However, within about 2-2 ½ years after that, the population levels were back to up what they were before the spill. So it shows that, those kinds of populations are quite resilient, they’re small organisms and they have high reproductive capability and they were able to re-populate the area pretty soon.

YOUNG: So at least by that measure of the impact of the spill, this is kind of a hopeful message for people today looking at what the ecological impact might be from the Deepwater Horizon spill.

TUNNELL: Yes, that’s correct. We have to be careful of going too broad with the inferences. Our fine-grained sandy beaches on the Texas coast are fairly easy to clean up and fairly quick to recover.

YOUNG: Uh huh. And that’s not at all the kind of coastline that’s being impacted now in southern Louisiana?

Ixtoc 1 oil well blowout in Bay of Campeche, 1979. Oil on water. (NOAA)

TUNNELL: Yes, you’re right on that. It’s, that area of the Mississippi Delta, the salt marshes that are in that area, are the most impacted, and the most difficult to clean up. To either side of Louisiana, on the sandy beaches of Texas and then Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, those fine grained beaches again, and so those are areas that can be cleaned up. But the Mississippi Delta again is really a problematic situation.

YOUNG: And what do we know about ecosystems roughly equivalent to wetlands that were affected by the Ixtoc spill back in ’79-‘80.

TUNNELL: Well that’s one of the things that kind of fell by the wayside. Unfortunately, both in Texas and in Mexico, once the spill was over with, capped off, and once the oil was cleaned up and most of the public places, the research funds stopped.

And so we don’t have, unfortunately, any comprehensive studies that were done to see the overall impact. There was one area in the southeastern corner of the Gulf of Mexico in the state of Campeche that has the tropical equivalent to the salt marsh that’s up there in the Mississippi Delta, and these are mangroves, they’re trees that actually grow at the edges of the water. And, supposedly they were pretty heavily impacted but there were no studies done and it was only anecdotal information that we have from that.

YOUNG: When you look at the Gulf today, what’s different that might affect this ecosystem’s resiliency now?

TUNNELL: That’s a really good question, and one that scientists are concerned about in the area. This resilience may have changed over these three decades of time. We’ve over-fished many of the fisheries there, we’ve used bad fishing techniques that have destroyed habitats, we’ve actually destroyed habitats of marshes and oyster reefs and things along the shoreline. Our dead zone that everybody’s aware of has expanded. So we’ve caused a lot of different kinds of detriments or insults to the Gulf of Mexico and it may not be as resilient now, than it was back 30 years ago.

YOUNG: Well given those big differences between the Ixtoc gusher and the Deepwater Horizon gusher, how useful is the Ixtoc by way of, you know, trying to guess what the ecological impact will be from this spill?

TUNNELL: Well I think it should give the people of the northern Gulf some hope that there is the ability for a recovery. I know they’re very down and decimated now because of what’s going on. I’ve heard some wanting to sell their houses and leave. I think there should be some hope that there is the possibility of recovery. It’ll take years in some areas along the beaches and maybe longer in those marshes, but there is a modicum of hope that they can be concerned for.

YOUNG: Dr. Wes Tunnell, Associate Director of the Hart Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies, thank you very much sir.

[MUSIC] Guy Lee “Turtles” from The Hurricane Waltz (Guy Lee/CD Baby 2008).

TUNNELL: Thank you Jeff, I enjoyed being with you.

Related link:

Wes Tunnell’s study of impacts of the Ixtoc 1 spill

Serious Money for Indonesian Forests

Deforestation causes 80 percent of Indonesia's greenhouse gas emissions. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

YOUNG: And now for some environmental news you might have missed since news of the oil spill broke. Norway made a bold move against climate change. It’s offering Indonesia a billion dollars to NOT destroy its rainforests. In exchange, Indonesia will stop clearing forests for two years. The idea is to lower the huge CO2 emissions that come from cutting trees. The results could be substantial—by some estimates Indonesia’s rapid deforestation makes it the world’s third largest emitter. Living on Earth’s Mitra Taj reports.

TAJ: This Norway-Indonesia forest deal is a big deal. A billion dollars is a lot of conservation money for a developing country… and the amount of carbon dioxide it could keep from escaping into the atmosphere could be just as impressive. Salman al-Farisi, a diplomat at Indonesia’s embassy in Washington DC, says 80 percent of Indonesia’s emissions come from deforestation.

AL-FARISI: This is a very important number. If we fail to do something on forests we will lose about two thousand islands in Indonesia. So this is not only environment, but also existence of our territory.

TAJ: To help keep parts of Indonesia from slipping into rising seas, last year Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono vowed to cut current emissions by a quarter by 2020. That’s more ambitious than the U.S. pledge. And now with this billion dollars from Norway, Indonesia is ready to say how it will make the cuts. For two years it will prevent oil palm and pulpwood companies from converting forests into plantations. Erik Solheim, Norway’s Minister of Environment and International Development, says it’s a sign Indonesia is serious.

SOLHEIM: This is a very brave step of president Yudhoyono making a moratorium. It may be he’s taking a big political risk and he should be praised for taking that step.

Oil palm expands onto nearly a million acres of tropical forest land in Indonesia every year. (Photo: Ingrid Lobet)

TAJ: Indonesia actually already has laws against turning forests into plantations, but officials frequently ignore them. This high-profile moratorium raises the stakes for enforcement. No carbon saved—no billion dollars.

SOLHEIM: They make their own decisions as to how they will reduce the emissions, and then they will get paid in accordance with results.

TAJ: But Solheim says there’s a fine line between ensuring success and dictating terms to a developing country. Norway has taken a delicate approach to negotiating some controversial parts of the agreement, like how much say forest communities will have in what happens to the land, and whether Indonesia will break current contracts with plantation companies

SOLHEIM: Ultimately that decision will have to be made by the Indonesians and not foreigners. I mean if anyone would come into Norway to tell us how to use natural resources, our oil our gas, or what we should do with out mountains, agriculture, we would not take to it very lightly. So we are not doing that.

TAJ: Indonesia and Norway want to produce clear details of their plan by fall. Fred Stolle is a forest specialist for the environmental think tank The World Resources Institute. He says that means they’ll need to answer a lot of questions soon.

STOLLE: Which is the institute who is getting that money? Will that institute work with Ministry of Forestry or the Ministry On Climate or the Ministry on Environment? How is the money divided? Does anybody in the field see the money? There’s no definition for natural forest, so secondary forest is not natural- can that still be converted? Are there enough projects to do with a billion dollars in a relatively short time frame?

TAJ: Ideally, the stickier elements of Indonesia’s deal, with Norway would have already been decided at the United Nations, as part of a new global treaty to address climate change. But those international talks have stalled, and with them—clear consensus on how countries, like Indonesia, should go forward. Fred Stolle says that adds to the importance of an agreement like this.

STOLLE: You know we have all those ideas, we have to stop tropical deforestation, but no one wants to pay for it. We said, ‘please Indonesia stop it, but, by the way, we don’t buy sustainable wood from you,’ and you have to think a developing country wants to develop- it’s a developing country. So Norway decided to go bilateral. They say, ‘let’s not wait because every year we wait, like a million hectares gets cut in Indonesia, so let’s start with that.’

How much say will forest people have in decisions that affect them? That part of the Norway-Indonesia agreement remains to be worked out. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

TAJ: Diplomat Al Farisi says Indonesia hopes the United States is watching the agreement with Norway and will consider something similar. President Obama has been expected to talk about forestry when he meets with President Yudhoyono, but he’s cancelled previous plans to visit Indonesia three times… most recently because of the oil spill in the Gulf. Al Farisi:

FARISI: We can understand because the domestic issue President Obama is now facing is also an issue shared by Indonesia. It’s about the environment, so we understand it. And, we still hope we can find some day, some time to welcome Obama to visit to Indonesia.

TAJ: For Living on Earth, I’m Mitra Taj in Washington.

Related links:

- Click here for more of Living on Earth's coverage of avoided deforestation.

- Indonesia's letter of intent with Norway

- Learn more from WRI about forests and international climate talks.

- Click here for a skeptical view of the partnership.

[MUSIC]: The JuJu Orchestra “This Is Not A Tango (The Dining Rooms Cinematic Remix) from Remixes 2 (Agogo Records 2009).

YOUNG: Coming up: Got raw milk? Maybe not for long, if some health officials have their way. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC]: Tomaz Stanko: “Terminal 7” from Dark Eyes (ECM Records 2010).

Heated Debate over Heating Milk

Farmer Edgar Plees and his cow Suzanne on the Boston Common. (Photo: Ian Stephens)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young. Some milk fans say they’re getting a raw deal. Raw, or unpasteurized, milk is the subject of intense debate in state legislatures across the country. Public health officials say it’s a threat. But raw milk proponents say the health and taste benefits outweigh the risks. Living on Earth’s Jessica Ilyse Smith has our story.

SMITH: On a sunny Monday morning on the Boston Commons, Suzanne the cow munches on grass and clover.

[COW MUNCHING, SOUND OF PROTESTERS TALKING IN BACKGROUND]

SMITH: In the heart of the city this is an uncommon scene. But Suzanne’s brown coat, blue collar and large cowbell draw attention during the 9 am rush. Kids run up to pet her. And the cow’s owner, Edgar Plees offers passersby a drink.

PLEES: Our cows have a high percentage of butterfat, which makes it a richer, creamier milk. Everyone who tastes it says, ‘wow, that tastes really different.’

SMITH: One of those tasters is Dennis Walsh who spots the cow and comes over to grab a Dixie cup filled with raw milk.

WALSH: It tastes creamy; it tastes like milk, really—you know what I remember it used to taste like. I would drink more milk if I had that.

SMITH: Taste is a selling point for raw milk advocates. Farmer Plees says there are reasons people want to drink the fresh, unpasteurized milk.

PLEES: It all seems very straightforward to me, of course, you drink the milk that comes out of the cow is going to be better than having it processed, or refined. It comes out of the cow, it’s chilled and that’s it.

Farmer Edgar Plees and his Jersey cow Suzanne on the Boston Common. (Photo: Ian Stephens)

SMITH: The farmer and his cow are here with protesters who have come to speak their mind on raw milk. Abby Rockefeller says the group is opposing the cease and desist letters served by the state of Massachusetts to truckers delivering raw milk to consumers.

ROCKEFELLER: I’m here because I drink raw milk and want to go on drinking raw milk and wish to have it available to me.

SMITH: The Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources is now deciding how to proceed with raw milk regulations. Rockefeller and other activists want to be able to buy raw milk that they say provides health benefits like a boosted immunity and lower rates of asthma. But many organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control, and the Food and Drug Administration, agree with most of the dairy industry that pasteurized milk is much safer.

MAPLES: Pasteurization allows you to have all of the benefits of raw milk, but without the risk.

SMITH: Isabel Maples is a spokesperson for the National Dairy Council. She says that when milk is heated to 161 degrees Fahrenheit for 15 seconds during pasteurization it kills harmful bacteria such as Salmonella, E. Coli, Listeria, and Campylobacter.

MAPLES: Because milk is so rich in nutrients and because it’s a liquid, the bacteria will spread easy from area to the next. And, because milk has a pretty neutral ph, bacteria can live and grow and thrive in milk. When the food is pasteurized it kills of most bacteria, but also increases shelf life of milk, too.

The National Dairy Council´s Isabel Maples

ROCKEFELLER: Bacteria are not our problem; bad farming practices are our problem. So you need to have farms that are run well, so you should have inspections and certification, not pasteurization.

SMITH: Abby Rockefeller says factory farms are a source of E. Coli 0157 one of the bacterial strains that worry many people. These large farms may have as many of 5,000 cows, and overcrowding and the overuse of antibiotics are common. It takes just one cow to contaminate milk, so pasteurization is important for large dairies. But raw milk drinkers say their milk comes from small-scale farms where milk goes directly from cow to bottle. Still, many people fear drinking unpasteurized milk. David Gumpert is the author of, “The Raw Milk Revolution: Behind America’s Emerging Battle over Food Rights.” He says the fear is overblown.

GUMPERT: Dairy in general rates very low in the food borne illness scheme of things- something like leafy greens are considered more dangerous by the public health community.

SMITH: Gumpert believes large dairy farmers feel threatened by the raw milk dairies. Raw milk farmers can earn between 5 to 10 dollars per gallon. That’s compared to $1-1.50 per gallon farmers get for pasteurized milk, which doesn’t cover their costs. This price differential means a lot to dairy farmers who are struggling to stay in business.

GUMPERT: Over the course of 1970 to 2005 we saw 88% of the dairy farms in the U.S. disappear, and the reason they disappeared is they could not get a good price for their milk selling it for pasteurization. I’m not suggesting that all dairies should be selling unpasteurized milk, but as an economic option for farmers, raw milk does offer an economic opportunity.

SMITH: Even though raw milk accounts for about three percent of the $140 billion dairy industry, Gumpert says that adds up, and demand is growing.

GUMPERT: If you add a percentage to that each percent is worth somewhere on the order of 1.4 billion dollars. Well now you’re starting to talk about some significant money.

David Gumpert author of The Raw Milk Revolution

SMITH: Unpasteurized milk is legal in 29 states, though most don’t allow retail sales in stores. Transporting the fluid across state lines is illegal. Last year Vermont passed a bill allowing the sale of raw milk, and created separate rules for raw and pasteurized milk production and sales. And in Wisconsin, America’s ‘dairyland state’, the Governor vetoed a pro-raw milk bill citing public safety concerns. He said a bacterial outbreak could taint milk’s image and cripple the state’s mammoth dairy industry. But raw milk activists say they favor regulating raw milk and that the issue comes down to freedom of choice. The National Diary Council’s Isabel Maples doesn’t buy it.

MAPLES: I have three teenagers. When they get in the car with me, and they don’t have their seatbelt on, I know that there are huge risks there. So, I’m going to be firm in making sure they buckle up. I look at raw milk in the same light.

SMITH: Raw milk proponent and author, David Gumpert, doesn’t deny that there are risks involved with consuming unpasteurized milk, but to him it’s not more risky than anything else.

GUMPERT: You know people can get sick from raw milk, they can get sick from pasteurized milk and they can get sick from any food. We take a lot of risks in all aspects of our life, and the question is how much risk are we willing to take to get the food we want?

SMITH: More states are expected to decide whether to allow raw milk sales in the coming year. Culinary choice, or risky gamble the heated debate over heating milk brings new meaning to ‘Got Milk?’ For Living on Earth I’m Jessica Ilyse Smith.

Related links:

- David Gumpert´s website

- Read “On the Safety of Raw Milk” from the FDA

- Read a full response by the Weston A. Price Foundation

- Visit the National Dairy Council’s website

- Visit the Farm-to-Consumer Legal Defense Fund to learn about raw milk regulations in your state

[MUSIC]: Various Artists/The Basic “Milk” from Soul Freedom: The Best Of The Jazzman 45’s (Jazzman/Kudos Records 2009).

Food That Reaches Back through Slavery

Judith Carney is the author of “In the Shadow Of Slavery: Africa's Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World.” (University of California Press)

YOUNG: For 145 years June 19th has been the day that many African American communities mark emancipation. Juneteenth, as it’s known, is a day for picnics and cookouts in honor of the end of American slavery. What’s not often appreciated at those gatherings is the role that slaves played in bringing some of those picnic foods to American tables. Living on Earth and Planet Harmony producer Ike Sriskandarajah explores how culture and agriculture overlapped in that dark chapter of American history.

SRISKANDARAJAH: For a thousand years before the Atlantic slave trade started, the origin of humanity was also its cornucopia. Many of the world’s staple foods first sprouted from African soil. They’re on your picnic table- from the sesame seeds on your bun, to the Worcestershire sauce in your hamburger, to your slice of watermelon. And if you reach into the cooler…

[COKE CAN]

CARNEY: The cola in coca-cola is an African plant as well- the cola nut.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Judith Carney, is the author of, “In The Shadow of Slavery, Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World.” Her book traces the path of food that traveled with slaves. Including an ingredient in the world’s most ubiquitous fizzy drink

CARNEY: Cola, came on slave ships- they used cola in the casks of water that were carried on the ships to refresh water that was going bad during the prolonged voyage

SRISKANDARAJAH: So they were drinking coke 400 years ago on slave ships?

CARNEY: No, no- (laughs)- you need the coca part of it to add the sugar, I think. The only thing, I would say it’s slightly more bitter than eating a potato raw.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Another of our favorite drinks, coffee, also comes out of Africa. And millet, black eyed peas… Judith Carney tracks the migration of these foods through historical records

CARNEY: I went back and looked at the journals and the diaries, what did the ship captains- the slavers- how are they feeding people for 6 weeks to 3 months voyages?

SRISKANDARAJAH: One such log was written by a seventeenth century slave trader, moored off the coast of Western Africa.

[BOAT, WAVES, SEAGULLS]

VOICEOVER: A ship that takes in 500 slaves, must provide about a hundred thousand yams; which is very difficult, because it is hard to stow them, by reason they take up so much room; and yet no less ought to be provided, the slaves being of such constitution, that no other food will keep them; so that they sicken and die apace.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The slaver’s human cargo was valuable. So captains bought food the captured Africans could eat, and they bought enough of it. Sometimes the ships would even land in the New World with surplus.

Judith Carney is the author of “In the Shadow Of Slavery: Africa's Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World.” (University of California Press)

CARNEY: And that I argue, the unwitting conveyance of bringing African food to the Americas, was the slave ship.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Once in the Americas the slaves were scattered to work plantation cash crops. But they were also expected to feed themselves.

CARNEY: We think of plantations as places that produced export crops, but we don’t think about them as places where human beings had to also know how to farm for their own nourishment.

SRISKANDARAJAH: A Danish Traveler, Johan L. Carsten’s, wrote a diary describing his observations of the Americas during the early Eighteenth Century

[FIFE MUSIC]

VOICEOVER: These plantation slaves received nothing from their master in the way of food or clothing except only the small plot of land at the outermost extremity of his plantation land that he assigns to each slave.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The staples from Western Africa flourished in the South, and from those meager plots came a rich food tradition. It was good enough for slaves, it was even good enough for a founding father. Culinary Historian, Michael Twitty says that Thomas Jefferson actually bought food from his slaves.

Michael Twitty curated the African American Heritage Seed Collection.

TWITTY: Oh yeah, oh yeah. The day-to-day needs of his own kitchen table, much of that was supplied by the enslaved population of Monticello. There are extensive records of purchases for the main house from the enslaved communities. He would buy cabbage, he would buy watermelon, he’d buy sprouts.

SRISKANDARAJAH: President Jefferson wasn’t alone.

TWITTY: Before the new immigrants come in at the beginning of the 20th century, we are the ethnic restaurateurs of America.

SRISKANDARAJAH: And Twitty says that African Americans didn’t just add ingredients to America’s Melting Pot- they spiced it up.

TWITTY: Red pepper was the most important, ubiquitous spice.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So important, that in 1780, close to 100 slaves, newly imported from West Africa, protested until plantation owner Josiah Collins supplied the spice.

TWITTY: Within a year of their arrival he has to order 1000 pepper pods to season their food because they will not eat bland food. They express to him that, ‘we want the pepper pods!’

SRISKANDARAJAH: Hot sauce has been on most southern tables since. African American cuisine still has its roots in those peripheral plots but, but African Americans’ connection to the land has changed.

TWITTY: We were an agrarian people for millennia even through the period of slavery- and we went from being 90 percent agrarian to 90 percent urban in less than a 100 years- think about that.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Freedom wasn’t free, emancipation cost the slaves their link to the land. African Americans couldn’t own or lease land, their only option was punitive sharecropping.

TWITTY: All that oppression hurt us in the long run because it divorced us from the land, it divorced us from nature and through food we can reconnect with that and begin to repair those links.

SRISKANDARAJAH: That’s part of Michael Twitty’s mission, he works to bridge that gap. He’s put together the African American Heritage Seed Collection. It offers heirloom seeds to today’s gardeners.

TWITTY: To see an okra plant that you know that was growing in Mt. Vernon or Monticello, to see a kind of rice grown in the rice plantations of 17th century South Carolina- it gives you the sense of such connection. Because I always tell people- my own corny saying, but: growing history is knowing history.

SRISKANDARAJAH: And knowing history can turn your bowl of gumbo into a portal back through time. For Planet Harmony and Living on Earth, I’m Ike Sriskandarajah. Happy Juneteenth.

Related link:

Check out Michael Twitty's seed collection from the Landreth Company

[MUSIC]: Carolina Cholcolate Drops “ Peace Behind The Bridge” from Genuine Negro Jig (Nonesuch Records 2009).

YOUNG: Planet Harmony invites everyone to the environmental discussion and has special appeal for young African Americans. Log in and lend your stories, audio, and video to our site at myplanetharmony.com.

Natural Poetry

Poet Ross Gay.

We’ve occasionally been bringing you poetry inspired by the natural world – and we have more today.

GAY: My name’s Ross Gay and I think I probably started writing poems when I was in college. I was a football player and I hadn’t done much reading before I got to college, though I did read comic books, and stuff like that. But I got to college and somehow was turned on to poetry in an American literature class and poets like Amiri Baraka, especially, actually made me have a response that was so strong, they sort of articulated things that I had not yet known how to articulate, but that I had felt very strongly.

And once I’d had that experience of being able to feel something more clearly, because I had it articulate for me, I wanted to sort of do the same thing, I think. And that’s how I started writing poems.

YOUNG: Ross Gay says now he’s a basketball coach, an occasional demolition man, a painter – and a gardener.

GAY: This poem is called “Ode to the Beekeeper,” and this is a poem, actually for my partner, who keeps bees, and you know, all of this information about colony collapse disorder- you know this had been very much on a lot of people’s minds and was very much on her mind- which got her to begin keeping bees. It’s called “Ode to the Beekeeper.”

Poet Ross Gay.

Who has taken off her veil and gloves and whispers to the bees

In their own language

Inspecting the comb-thick frames

Blowing just so when one, or the other, alights on her, if she doesn’t study it first

The veins feeding the wings, the deep ochre shimmy, the singing

Just like in the dreams that brought her here in the first place

Dream of the queen, dream of the brood chamber, dream of the desiccated world, and sifting with her hands the ash

And her hands ashen when she awoke

Dream of honey in her child’s wound

Dream of bees hived in the heart and each wet chamber gone gold

Which is why, first, she put on the veil

And which is why, too, she took it off

YOUNG: As well as writing poetry, Ross Gay teaches creative writing at Indiana University at Bloomington.

Related link:

Click here for more on Ross Gay

[MUSIC]: The Crusaders “When There’s Love Around” from Southern Comfort (Verve Music 1974).

Earth Ear

Newly hatched tern and incipient sibling. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender/Salt Marsh Diary)

[TERNS]

YOUNG: We leave you this week with a phrase of terns.

[TERNS]

YOUNG: Mark Seth Lender accompanied some U.S. Fish and Wildlife scientists to Falkner Island during their annual nest count of Common Terns and the endangered Roseate Tern. Falkner is located off Guilford Connecticut in Long Island Sound, and it’s one of the terns' last safe retreats, and their angry cries send a clear message: ‘Keep Out!’

Terns of Falkner Island in Long Island Sound warn humans to stay away from their nesting grounds. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender/Salt Marsh Diary)

YOUNG: To see some of Mark’s photos of the Falkner Island terns, go to our website LOE.org.

YOUNG: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Annie Glausser, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, and Mitra Taj, with help from Sarah Calkins, and Sammy Sousa. Our interns are Amanda Martinez and Meghan Miner. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Steve Curwood is our executive producer. You can find us anytime at LOE dot org. – and check out our new Facebook page – PRI’s living on earth. I’m Jeff Young. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth hormones on their cows. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners. The Ford Foundation, The Town Creek Foundation, The Oak Foundation—supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues. And Pax World Mutual Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at Pax world dot com. Pax World for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI – Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth