July 23, 2010

Air Date: July 23, 2010

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Dispersant Discussion

View the page for this story

Nearly 2 million gallons of chemical dispersants have been applied to the Gulf of Mexico in the wake of the BP oil leak. Host Jeff Young reports that many of the country's leading marine scientists have signed a consensus statement against the use of dispersants on that scale. (08:30)

Oil in the Air

View the page for this story

The oil in the Gulf isn’t just damaging the ocean. It’s also compromising the air. The EPA has been widely monitoring air quality along the Gulf coast since the spill began, but a local advocacy group, the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, says it’s not enough. Host Jeff Young talks with Anne Rolfes, director of the Bucket Brigade, about what she thinks the EPA is missing. (03:30)

Green Camp

/ Sean PowersView the page for this story

Camps these days offer more than just swimming, volleyball, and archery. At an environmentally themed Camp in Savoy, Illinois, 5-9 year olds learn about green issues, including the Deepwater Horizon oil blowout. Sean Powers reports. (04:45)

NOAA Signed Off on Gulf Drilling Plans

/ Mitra TajView the page for this story

The agency charged with protecting key marine species approved offshore drilling plans for the Gulf of Mexico, including the BP well that has gushed out the biggest oil spill in U.S. history. Living on Earth's Mitra Taj reports that NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, failed to use its Endangered Species Act authority to prevent or prepare for the spill now threatening marine mammals and turtles in the Gulf. (06:45)

Drilling Down on Fracking

View the page for this story

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a process used to extract natural gas from shale deposits deep within the earth. Natural gas could help the U.S. meet its CO2 emissions-reductions goals, but many environmental problems, including water pollution have been associated with extracting this resource. Host Jeff Young talks with Christopher Flavin from the WorldWatch Institute about how regulating the natural gas industry could make this process more environmentally friendly. (06:40)

Remembering a Nobel Climate Scientist

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

Stephen Schneider, one of the world’s foremost climate scientists, died suddenly earlier this month. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood recalls Schneider’s many contributions to climate research and public policy. (03:40)

Beetle Ranching

/ Emma JacobsView the page for this story

Purple loosestrife is a beautiful but invasive wetland plant that spreads quickly and pushes out native species. A tiny beetle has been found to attack purple loosestrife. Emma Jacobs reports that volunteers are more than willing to help propagate the predator. (05:20)

Recipe for Raising Chickens

View the page for this story

With urban chicken farming gaining popularity, a 36-page illustrated booklet from 1975 is becoming an increasingly popular guide. Nancy Rekow recorded the long life and chicken raising lessons of Minnie Rose Lovgreen, and shares her experiences and memories with host Jeff Young. (07:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Jeff Young

GUESTS: Bob Shipp, Susan Shaw, Sylvia Earle, Mark Bushman, Anne Rolfes, Ernie Moniz,

REPORTERS: Sean Powers, Mitra Taj, Steve Curwood, Emma Jacobs.

EARTH EAR: Jeff Rice.

[THEME]

YOUNG: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. Some two million gallons of chemical dispersants went into the Gulf of Mexico’s oily waters. Now some deep thinkers in marine science say that weapon against the spill has done more harm than good.

SHIPP: I think almost all of us in the marine sciences area who study the ecosystem are in agreement that the use of dispersants is a terrible choice.

YOUNG: We explore how dispersed oil affects the Gulf’s food chain. And kids at a green summer camp tackle the oil crisis

KID: There's far enough oil on land. We don't need the oil in the ocean. I don't think we need more oil at all. It's like stealing from the sea life's home.

YOUNG: Wisdom out of the mouths of babes -- also we remember a global warming warrior--climate scientist Stephen Schneider. Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000).]

Dispersant Discussion

A plane sprays dispersants over the leaking oil in the Gulf of Mexico. (NWFBlogs)

YOUNG: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios in Somerville MA this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. Well, since late April some 1.8 million gallons of chemical dispersants were sprayed on the Gulf of Mexico’s oiled surface or injected deep into the plume escaping BP’s Macondo well.

Now toxicologists and marine scientists are calling for an end to wide use of chemical dispersants and the start of more focused research into the harm dispersants may have caused.

SHAW: It’s a controversial thing, the use of dispersants, because the ecosystem down there is so toxic this will be a legacy for decades to come. Not months, not years… decades.

Marine toxicologist Susan Shaw authored the consensus statement opposing the use of chemical dispersants in the Gulf of Mexico.

SHIPP: I think almost all of us in the marine science area who study the ecosystem are in agreement that the use of dispersants is a terrible choice.

YOUNG: That was Marine Sciences Professor Bob Shipp, and toxicologist Susan Shaw. They’re among scientists circulating a petition opposing chemical dispersants. Oceanographer Sylvia Earle was the first to sign on.

Earle is a pioneering figure in ocean science. She’s explorer-in-residence at National Geographic, and in the early 90’s she was chief scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. NOAA is one of the federal agencies that allowed the broad use of dispersants in the Gulf crisis. Sylvia Earle says that was a mistake.

EARLE: The role of dispersants is exactly what the name suggests: that is to break the oil up into small pieces and spread it widely. When applied at the surface, it means that the oil sinks, it is no longer a problem for those who are trying to clean up the oil, becomes a problem, though, for the oceans…looks as though it’s gone- it’s not gone- it just becomes a part of the ocean system.

A black tip shark swims through oil in the Gulf of Mexico. (NWFBlogs)

The real goal should be to get the oil out of ocean rather than to keep it in the ocean. And, the second thing is, in small pieces it becomes available and touches many more creatures in the water column than it does if it’s just floating on the surface.

YOUNG: Sylvia Earle’s name adds some heft to the scientists’ petition. It was written by Susan Shaw, a toxicologist who directs the Marine Environment Research Institute in Maine. Shaw dove into this issue—literally. She swam in the Gulf’s dispersed oil to gather samples. She found the combination of dispersant and oil is more toxic than either material alone.

SHAW: The dispersant acts like a delivery system for oil in the water. And oil contains hundreds of compounds that are toxic to every organ in the body and many are carcinogens. So if you have the dispersants making that oil more easily moving into cells and organs of the body, you have a much more toxic oil than just crude oil alone.

A plane sprays dispersants over the leaking oil in the Gulf of Mexico. (NWFBlogs)

YOUNG: Other scientists are documenting the early effects of that combination Shaw describes. Marine Sciences professor Bob Shipp of the University of South Alabama is measuring the organisms at the base of the Gulf’s food chain.

SHIPP: Take for example, an anchovy. An anchovy swims through the water with its mouth open, filtering food with its gill filaments. If it has to swim through a mass of water that has oil in it, those oil droplets will collect on the gill filaments and the anchovy will die. Now the anchovy, as well as many other species, is the major link between plankton and the higher members in the food web.

The same thing happens with the plankton, many of the little plankton organisms, almost microscopic, filter feed. And when they filter the oil it’s going to kill them. So most of us feel like using dispersants and putting oil in the water column is absolutely the worse thing that could happen.

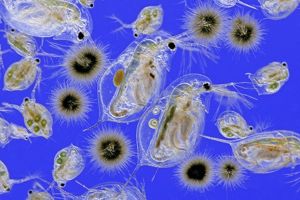

Plankton are the tiny microscopic organisms that make up the base of the ocean food web. Scientists are concerned that these filter feeders are eating oil and will bioaccumulate in higher sea life. (Wellcome Images)

YOUNG: Bob Shipp at the University of South Alabama. The main dispersant used, COREXIT, is made by the Illinois-based company Nalco. Nalco spokesperson Mike Bushman says Corexit has approval from the Environmental Protection Agency.

BUSHMAN: Our product is safe. It biodegrades very rapidly. It does what it’s intended to do which is to break the oil into droplets where it can biodegrade more rapidly in the water column. We have provided that service and made available whatever we have been requested to provide.

YOUNG: Nalco was criticized for not providing information, especially about COREXIT ingredients. Bushman says that information is now available. But, when a Senate subcommittee asked Nalco executives to testify at a July 15th hearing on dispersants, they declined. That left government officials like EPA administrator Lisa Jackson to take the heat. Jackson told the panel that this is the most dispersants that have ever been used on a U.S. oil spill.

JACKSON: BP had gotten up to 70,000 gallons of chemicals used in one single day. That was an alarming number.

YOUNG: In late May EPA told BP to scale back its use of dispersants and to switch to products less toxic than COREXIT. But subcommittee chair, Maryland Democrat Barbara Mikulski, reminded Jackson that BP largely ignored EPA’s demand for weeks. And Senator Mikulski took Jackson to task.

MIKULSKI: Often we’re told, “Don’t worry honey. We’ll take care of you and it won’t hurt.” We only then find out that what we thought was a good product turns out to have vile consequences. I don’t want dispersants to be the agent orange of this oil spill.

JACKSON: Madame chairman we are in a situation with no perfect solution.

YOUNG: Again, EPA’s Lisa Jackson.

JACKSON: Because there are scientific unknowns we had to make decisions that are a series of trade-offs. At the time we were risking that which we’ve all seen on TV, which is large amounts of oil at the surface, which got by the skimmers and got by the burners and would end up in the marshes where they do the most damage, and in the shallows. That trade off isn’t easy.

YOUNG: Jackson says EPA continues to test the toxicity of COREXIT. Marine scientist Bob Shipp was also scheduled to testify at that Senate hearing. But he broke his foot and couldn’t travel. Had he been there, Professor Shipp might have picked a bit of a fight with Administrator Jackson. He says EPA’s testing misses the point.

Dr. Bob Shipp chair of the marine science department at the University of South Alabama. (Photo: Bob Shipp)

SHIPP: I think there is a red herring here with this talk of toxins, you know, whether the dispersants are toxic or not. They’re toxic but that’s not the main concern. The main concern is they are putting them and oil in the water column and that’s lethal to much of the life that lives there.

YOUNG: This is the major tool that BP and government agencies have been relying on.

SHIPP: Yes, [laughs] that’s right. What’s the purpose of it? It’s to hide it. Out of sight, out of mind. And it makes no sense at all. If you use dispersants on a limited spill on the surface that’s ok. But this spill is so massive that the justification, you know, that if we use dispersants it won’t get to the marshes…that’s not true. So, the use of dispersants is just totally unjustified.

YOUNG: Part of the petition Professor Shipp and other scientists are signing says, “The use of dispersants does not represent a science-based, quantifiable “tradeoff” but rather amounts to a large-scale experiment on the Gulf of Mexico. Oceanographer Sylvia Earle says the lack of solid science about dispersants should have led decision makers to be more cautious about their use.

EARLE: The precautionary principle would seem to be the wise course of action rather than, ‘let’s just do it and then see what happens.’

Dr. Sylvia Earle is a National Geographic Explorer in Residence and the 2009 TED Prize Winner. (National Geographic)

YOUNG: The Obama administration has made a strong point that it will make policy based on science. Does this seem to you like a decision based in science?

EARLE: The policies that are in effect are based on previous experience. That led those at the time to think that this was, perhaps the best course of action to protect beaches and marshes. And, from the coast’s standpoint the place where most of the people are, you have helped solve the problem.

But if you think like an ocean, which is how I tend to think, you’ve caused a greater problem. It is frustrating to see the consequences of what is happening and the inability to do what seems like the right thing to do sometimes. But perhaps the effects of what has happened now will cause a re-thinking of these policies.

YOUNG: Pretty painful way to learn a lesson.

EARLE: Very painful. But, let’s hope we do learn. The greatest tragedy would be if we have lived through this experience for the last three months and failed to change our ways as a consequence of it.

YOUNG: You can hear more of our interview with Sylvia Earle and read the scientists’ consensus statement on dispersants at our website LOE dot ORG.

Related links:

- Dr. Sylvia Earle’s home page

- Click here to read the scientist’s consensus statement on the use of dispersants.

- Bob Shipp’s home page

- Susan Shaw is Director of the Marine Environment Research Institute

- Click here to hear an extended interview with Dr. Sylvia Earle

Oil in the Air

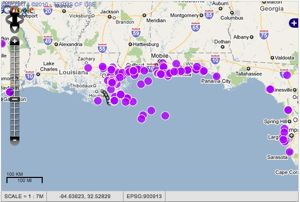

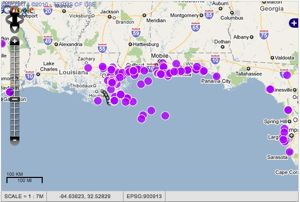

Oil Spill Crisis Map. (Image: Louisiana Bucket Brigade)

YOUNG: It’s not just the water that has people worried on the Gulf coast. Air quality data recently released by the government show high levels of some hydrocarbons downwind of the blown-out well. EPA has been monitoring air quality along the Gulf coast widely, but an advocacy group, the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, analyzed the EPA data, and found some shortcomings. Anne Rolfes directs the Louisiana Bucket Brigade.

ROLFES: What we found is that there are tremendous gaps in the EPA samplings. While the EPA does have a monitoring network, there are a lot of problems in this area including terrible odors, and health complaints that are not being accounted for by those monitors.

YOUNG: What do we know from the monitoring we have about the level of chemical exposure that people might be suffering?

ROLFES: The EPA data show hydrogen sulfide to be an area of concern, there have also been repeated benzene readings when they have gone out and sampled for it.

(Photo: United States Coast Guard)

YOUNG: And benzene, that’s a carcinogen, isn’t it?

ROLFES: Yeah benzene is known to cause leukemia; it’s a class A carcinogen. Now we’re not saying that everybody who’s exposed is going to get cancer tomorrow, but we are raising a flag about ongoing prolonged exposure in the Gulf Coast.

YOUNG: So, how do you know that there are gaps in what EPA is telling you? What do you have to point at and say, “Hey you’re missing things here!”

ROLFES: We have created an oil spill crisis map which is a very simple way for an ordinary person to report that they smelled something terrible, that maybe their head hurt, or their child got asthma when the child has never had asthma before.

These reports show up on a map and they’re either orange dots or blue dots, and we can pair the location of those dots with the location of the EPA monitors. And what we’re finding out is that there are very few dots that represent EPA monitors.

Oil Spill Crisis Map. (Image: Louisiana Bucket Brigade)

Whereas there are hundreds of dots that represent health and odor complaints, and a lot of those complaints are not in areas where EPA has monitors. They cannot be everywhere at one time, and so we think that the best thing to do is to arm ordinary community members with the tools that we need to go out and take samples for ourselves.

YOUNG: So you want EPA to what, hire on local folks to do some of the air monitoring?

ROLFES: There is a whole class of people here who are out of work: fishermen, shrimpers, oystermen, anybody who had anything to do with the seafood industry. And they are also the perfect people to now going forward monitor the environment. If you think about it who knows the marshes and the bayous better than anybody.

We’re just living down here, we’re guinea pigs in a living laboratory. And all we’re saying here is, improve the data collection so that we can get a little bit more knowledge for this laboratory of ours.

YOUNG: Anne Rolfes with the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, thank you very much.

ROLFES: Thanks a lot, Jeff. We appreciate y'alls interest.

Related links:

- Visit the Louisiana Bucket Brigade website

- Take a closer look at the Oil Spill Crisis Map

- Read the Louisiana Bucket Brigade’s report

[MUSIC: Trombone Shorty “Quiet As It’s Kept from Backatown (Verve 2010).]

YOUNG: Just ahead, what the booming natural gas supply might mean for our climate and water. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Bad Plus: “Human Behavior” from The bad Plus 3 Pak (EP) (Sony Music 2001).]

Green Camp

A simulation of the Gulf spill; children try to collect vegetable oil from water.

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young. The oil may no longer be pouring out of BP’s well, but the oil disaster reaches far beyond the shorelines of the Gulf States. Reporter Sean Powers visited a green camp in Savoy, Illinois where a group of kids learned about the spill and how it’s affecting their lives.

GIBSON: Can you explain what’s going on?

KID: Animals are dying because of the oil spill.

POWERS: Well inland from where the Deepwater Horizon oilrig burst into flames, a group of five-to-nine year olds share what they know about the disaster with their camp counselors. They talk about everything from the explosion that triggered the spill to the oil-soaked pelicans.

KID: I can’t imagine all those little sea creatures dying…

POWERS: The kids sit in a circle as Holly Gibson, one of the camp leaders, shows photos of animals drenched in oil, and maps of the oil’s reach along the Gulf.

Straws stand in for booms to corral the oil: it’s not very effective.(Photo: Sean Powers)

HOLLY GIBSON: Notice it’s already down by the tip of Florida, it’s all the way up here by Louisiana, and Mississippi, and Alabama.

KID: The tip of the Florida? Oh man.

HOLLY GIBSON: It has covered a lot of the Gulf of Mexico by now.

KID: Is it ever going to come to our town?

HOLLY GIBSON: No, it won’t come up into Illinois.

KID: It won’t come up to Illinois because we’re right in the middle. There are no oceans near Illinois.

POWERS: But that hasn’t stopped this group from worrying about the oil. The kids are about to witness a simulation of the spill. Genny Gibson directs Green Camp, and she watches on as another camp leader fills a large rectangular tank of water with vegetable oil. Bubbles start to form.

[BUBBLING]

(Photo: Sean Powers)

KID: It’s very thick.

GENNY GIBSON: Are those spots getting bigger?

KIDS: Yeah, that means it’s spreading...it’s spreading…it’s spreading.

POWERS: The kids try to rescue small paper fish from below the surface by separating the oil from the water using cotton balls and buoys made out of strings and straws.

[SFX FISH]

KID: Fish! Fish! Fish!

JULIE GIBSON: Oh, you got a fish?

KID: I scooped it up out of the water.

POWERS: One camp counselor sprinkles cornstarch to solidify the “polluted” water. The kids then scoop it up with the makeshift buoys, but that’s becoming an even greater challenge.

[SFX]

KID: Because when we try to bring it up, it immediately dissolves into liquid, so we can’t bring it up.

GENNY GIBSON: Then it’s easier to pump up the water, and then extract it out.

KID: Ewww, it’s getting dirtier. There’s still some oil down there.

POWERS: After the experiment, the kids write in their journals about what they learned. Most of them, like nine-year-old Rachel Silvey, reflect on the wildlife strewn across shores and covered in blackened crude oil.

A simulation of the Gulf spill; children try to collect vegetable oil from water. (Photo: Sean Powers)

[SFX]

SILVEY: What I saw on the news was that we had like a mom and a baby crab and a dad. The dad was caught in a rope, and the baby and the mom were trying to escape, which they did. But the father died because the oil was coming closer, closer, and closer any minute. He got trapped in the net, and he just died. Pretty sad.

POWERS: Kids relate situations like environmental disasters to their own experiences, says Diane Levin. Levin teaches at Wheelock College in Boston, and helps educators talk about traumatic events with children.

LEVIN: When we talk to them, it’s really important to not just assume we can explain it all to them, and they’ll understand it because they do bring their understandings of families to it, or their understanding of when they get dirty what happens so they then relate what they’ve heard to themselves and it can lead to fears and worries.

POWERS: Levin says children should see both sides of the story: images of animals covered in oil and animals being cleaned up. But she also says it can be very helpful for kids to try to find solutions to fix the problem. Lucas Wood and Mira Schweitzer, both seven, are doing just that…

[DRILLING]

WOOD: I think we shouldn’t take oil from the sea. We should only take it from the land. We don’t need the oil in the ocean.

SCHWEITZER: I don’t think we need more oil at all.

WOOD: It’s like stealing from the sea life’s home….

SCHWEITZER: It actually is pretty much stealing.

WOOD: Although they don’t need it, it can kill them.

POWERS: Some of the other ideas floating around at the camp range from using a giant hammer to plug the well, to sucking up the oil with a giant vacuum, to building a wall that would capture the oil.

Sure, some of these ideas might seem far-fetched, but this group says it’s better than nothing. Experts, like Diane Levin, say children should know it’s a grownup’s responsibility to fix the spill, but kids can benefit from thinking about what they can do closer to home to take care of the environment.

For Living on Earth, I’m Sean Powers in Savoy, Illinois.

YOUNG: To see a video of the oil spill simulation, visit our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- To see a video of Green Camp’s oil spill simulation, click here:

- Diane Levin’s website

- How to Talk With Kids About the Gulf Oil Spill (National Wildlife Federation)

- Talking with Kids About News (PBS Parents)

NOAA Signed Off on Gulf Drilling Plans

A NOAA veterinarian cleans an oiled Kemp's Ridley turtle. Most of the more than 700 sea turtles found dead since the spill are endangered Kemp's ridley turtles. In 2007, NOAA estimated 60 endangered and threatened turtles could be affected in the event of a major oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. (Photo: NOAA/GADNR)

YOUNG: The federal government is looking into what went wrong in the Gulf, including what the government did wrong. Administration officials say they’ve already addressed one problem area—the obscure Interior Department office called the Minerals Management Service.

MMS, as it was known, was notorious for ethical violations and lax oversight of offshore drilling. That office is being restructured and renamed. But critics say that’s not the only government agency that needs to change. Living on Earth’s Mitra Taj takes a look at NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and its role in offshore drilling.

TAJ: Since the Deepwater Horizon explosion, NOAA, the only federal agency charged with protecting struggling sea species, has swung into crisis mode—it’s tracking oiled and dead animals, and advising actions to soften the blow to key species: sperm whales, gulf sturgeon, sea turtles (many now swimming in an ocean of oil). But three years ago NOAA helped open the door to the country’s biggest oil spill by signing off on the government’s offshore drilling plan for the Gulf of Mexico.

Brendan Cummings is senior attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity, an environmental group suing NOAA and others in the wake of BP’s accident. He says NOAA failed its mission:

CUMMINGS: They’re charged with being advocates for wildlife, and figuring out what wildlife needs, particularly endangered species, and making sure other federal agencies as well as industrial entities such as BP comply with the law and carry out their activities, if at all, in a manner consistent with protecting these species. And, instead they just say go right ahead, looks good to us, we can’t possibly foresee a problem here.

A NOAA veterinarian carries a dead endangered sea turtle to an examining table for an autopsy. (Courtesy of NOAA)

TAJ: In its 2007 biological opinion on the country’s five-year offshore drilling plan for the Gulf of Mexico, NOAA wrote that oil and gas leases would be unlikely to jeopardize threatened and endangered species, or harm critical habitat.

Nine months after NOAA’s approval, the government sold BP the right to drill the Macondo well. NOAA officials declined to comment on the record, but those familiar with NOAA describe an agency restricted by bureaucratic obstacles and budget woes from enforcing the full extent of its environmental laws.

Keith Rizzardi is an attorney who writes a blog about the Endangered Species Act.

RIZZARDI: In this case I think NOAA did a fairly good job of trying to identify potential problems, but in the context of this disaster what stood out was no effort to address an oil spill of this magnitude.

It was the glaring weakness—call it Monday morning quarterbacking if you will, but that’s what didn’t get thought about here.

TAJ: In its 2007 opinion, NOAA described a worst-case spill scenario dwarfed by the current crisis. About 300 times the amount of oil NOAA thought could spill into the Gulf over a 40-year period has gushed out in three months.

NOAA’s modest spill estimate came courtesy of MMS, the agency found so susceptible to industry influence that the Department of Interior recently tore it into three pieces. Kyla Bennett, a former EPA official and whistleblower, says NOAA never should have trusted MMS’s assumptions.

BENNETT: I think it’s very scary to have the resource agencies like NOAA or Fish and Wildlife Service or EPA rely on information from agencies like MMS who in turn are usually relying on information provided by the applicants.

MMS employees were, in certain cases, rewarded for issuing leases. They are bean counters. Their job is to get those leases and permits out, not to stop them.

TAJ: And Bennett says fixing that problem could be expensive.

BENNETT: The reason that the federal agencies like NOAA rely on information provided by other agencies like MMS is because they don’t have the resources within their own agency to do an independent comprehensive review.

TAJ: Last year, NOAA itself raised concerns about the accuracy of MMS’s oil spill predictions. In September, NOAA administrator Jane Lubchenco warned that the agency wasn’t using best available data and was generally underestimating spill sizes. But NOAA didn’t change its opinion on offshore leases in the Gulf of Mexico, or demand to review specific projects going forward.

Again, Brendan Cummings with the Center for Biological Diversity:

CUMMINGS: You know, they do the big picture analysis—broad brush, pretty superficial, overly optimistic, and we would argue flawed. Then at each subsequent step, NOAA either does nothing or they just point back and say, ‘yes we already looked at it, no need for new analysis.’

And, my experience with NOAA is that when their role is purely advisory, and therefore can be ignored, they actually take good strong positions, but when they’re playing the role of enforcer, NOAA is afraid to actually ever say no.

TAJ: But Endangered Species Act expert Keith Rizzardi says it’s not so much a character flaw NOAA suffers from, as a semantic obstacle laid out in federal code. Over the years the courts have decided the Endangered Species Act should apply only when an event is “reasonably certain to occur.”

RIZZARDI: And, the conclusion here was that Deepwater Horizon was not reasonably certain to occur. But unfortunately—it did.

TAJ: Rizzardi says amending the Endangered Species Act to include less likely disastrous events could have meant a better backup plan for the Gulf: relief wells drilled, an already-constructed “top hat” container, skimming vessels ready for deployment, and information on how to best use chemical dispersants.

While the Obama administration is deconstructing MMS, it hasn’t said anything about beefing up NOAA’s role as an environmental check on offshore drilling. But Rizzardi says the topic will probably resurface as the search for oil and gas reaches further and deeper into marine habitat.

RIZZARDI: I think the tension we’re facing is a tough one because on the one hand you’re thinking about the existence of these species, you know, whether or not our kids are going to go see turtles and whether some undiscovered deep sea coral will ever be found and become the cure to some unknown disease. And on the other hand you have at stake our ability to explore for oil and our reliance on foreign oil and our domestic economy, and we need to find ways to reconcile these tensions and achieve our economic goals while adequately protecting our environmental needs.

TAJ: Concerns about striking the right balance recently stopped natural gas exploration in Alaska’s Chukchi Sea, after a federal judge determined not enough was known about how the lease might harm wildlife there.

For Living on Earth, I’m Mitra Taj in Washington.

Related links:

- Click here for NOAA's 2007 biological opinion on oil and gas drilling in the Gulf of Mexico.

- Read NOAA's 2009 recommendations for MMS.

- Click here to read Keith Rizzardi's ESA blawg.

- Read about the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services' role in approving of MMS oil and gas leases.

- Click here to learn about Gulf marine life affected since the spill.

- Learn more about NOAA's response to the oil spill.

[MUSIC: Greyboy All Stars “Genevieve (Quantic Remix)” from Soul Mosaic (Ubiquity Records 2004).]

Drilling Down on Fracking

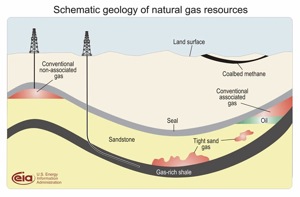

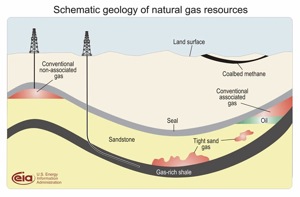

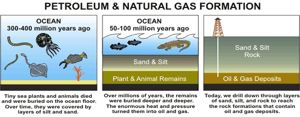

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, has made natural gas from the shale layer a feasible natural gas resource. (Photo: U.S. Energy Information Administration)

YOUNG: Natural gas is a hot topic. A spate of high profile reports and a series of public hearings this month explore the pros and cons of this booming energy source. The Environmental Protection Agency is getting public input as it considers regulation for what’s commonly called “fracking.”

Hydraulic fracturing releases natural gas from deep in the earth by injecting water and chemicals into layers of shale. As EPA is hearing, fracking is also creating problems. Colorado resident Tracy Dahl held a vial of murky water as he spoke at the hearing in Denver. He blames a gas fracking operation for damaging his drinking well.

DAHL: We are forced to travel 80 miles to obtain potable water. To have fought so long and hard to protect our water resources and in the end to have to see them impacted regardless, has been most frustrating experience of my life.

YOUNG: Wyoming rancher John Fenton said his water is also contaminated.

FENTON: I don’t have a problem with production of oil, or natural gas or any of our other natural resources, but it shouldn't come at the expense and the degradation of the things we truly can not live without: our air, our water, and our health. The monetary gains, the jobs are nice, but we have to look after health and basic human needs of everyone on this planet. [Applause].

YOUNG: Stories like that got an even broader audience with the surprise success of a documentary film called Gasland.

[GASLAND TRAILER “Sometimes it bubbles and hisses when it comes out.”]

YOUNG: In one scene, tap water from a well apparently tainted by drilling, catches fire.

[SOUND of flames then “whoah, Jesus Christ!”]

YOUNG: A similar exploding tapwater story has become legendary in Pennsylvania, where fracking is a front burner issue. The gas-rich Marcellus shale formation stretches from West Virginia north to upstate New York. A recent industry report estimates that gas could be worth two trillion dollars. MIT also studied the prospects for natural gas. MIT energy initiative director, Ernie Moniz, says part of its appeal is that it’s less carbon intensive than other fossil fuels.

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, has made natural gas from the shale layer a feasible natural gas resource. (Photo: U.S. Energy Information Administration)

MONIZ: Gas really is a bridge to a low carbon future.

YOUNG: So on the one hand, a cleaner, abundant fuel; on the other, a threat to clean water. WorldWatch Institute director Christopher Flavin’s analysis finds the supply of natural gas coming on line is a game changer for U.S. energy policy. Mr. Flavin says that allows us to think of gas as a long-term replacement for oil and coal.

FLAVIN: If you replace an existing coal fired power plant with a new natural gas plant, you get about a two-thirds reduction in the carbon dioxide emissions. And, since we get close to half of our total electricity from coal currently, you could envision shifting a large fraction of our electricity generating capacity and thereby getting a big reduction to emissions.

Natural gas also produces a lot less of the more conventional pollutants that cause various kinds of lung damage and other human health problems, so across the whole range of environmental indicators, gas is superior to coal on almost every score.

And, the exciting thing about natural gas is it would also facilitate the development of the renewable resources. Things like solar and wind power are intermittent by nature and you need to have a back-up capacity and ideally a low-carbon back up. Renewables and natural gas really fit together very well in that way. I would argue that the combination of gas and renewables could allow us to replace most, if not all, of our coal fired electricity over the next 20 years.

YOUNG: So you’re pointing to some really big potential benefits here. But, most of what we hear are environmental downsides. People are really upset about fracking. Is there a bit of a split here within environmentalism?

The formation of natural gas. (Photo: U.S. Energy Information Administration)

FLAVIN: Well there’s been this tremendous boom in shale gas development. And that rapid development of the industry has meant many areas where there is not a solid regulatory structure in place, and I think also cases where the industry itself, many of the companies, have not developed solid environmental practices.

This sort of “gold rush” type of boom mentality has meant that there are practices being employed that are in fact leading to various kinds of environmental problems including the contamination of water supplies, unexpected blowouts of wells, air pollution, and just disruption from turning what had been relatively pristine rural areas into semi-industrial zones.

One of the things the industry has been fighting for that I think really is not justified is that they have fought any requirement that they disclose the chemicals that are put into the water. And it simply is something that needs to be done. And certainly any chemicals that are found to be toxic or potential carcinogens should simply not be allowed to include in those hydro-fracturing fluids.

YOUNG: There’s a lot at stake here for the vested interests in the electric utility area. What’s the response from the coal lobby to this potential for serious, large-scale switching over to another fuel?

FLAVIN: Well, behind the scenes the coal industry has been working very hard to really stop the development of natural gas generation in its tracks. Arguing that the supplies are really not as large as what other analysts say, arguing that this is just really not a secure way to provide electricity.

And really this sort of effort by the coal industry is doing enormous environmental damage because coal is not only responsible for a very large fraction of our greenhouse gas emissions, it’s really replacing that coal is one of the simplest, cheapest things we could do in terms of reducing the impact on the climate.

But coal is also responsible for a whole range of ecological and health problems. So I think those environmentalists that are quick to condemn natural gas should really think very closely about the alternatives and perhaps think about joining a coalition of both environmental and clean energy groups that are working to ensure that gas is developed in the most responsible way, that it can actually play a productive role in a clean energy future.

YOUNG: Worldwatch Institute president, Christopher Flavin. Thank you very much.

FLAVIN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Click here to read the MIT report, “The Future of Natural Gas”

- Click here to read the WorldWatch Institute report, “The Role of Natural Gas in a Low-Carbon Energy Economy”

- Click here to learn about upcoming EPA hearings concerning fracking

- The EPA’s hydraulic fracturing page

[MUSIC: Hot Tuna “Belly Shadow” from Hot Tuna (BMG 1996).]

YOUNG: Coming up, the courageous life of a lady who wrote about chickens. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Booker T And The MG’s: “One Who Loves You” from Green Onions (Atlantic records 2004 reissue).]

Remembering a Nobel Climate Scientist

Stephen Schneider. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young. It was a tough week for advocates of action on climate change. Senate Majority leader Harry Reid announced that Democrats will not attempt to pass a climate bill this session—the votes simply aren’t there for even a watered down cap on carbon emissions. That news came just days after climate science lost a champion. Stanford Professor Stephen Schneider died suddenly July 19th at age 65. Professor Schneider was on the cutting edge of climate change science and policy for some four decades, first as a biologist and then as an eloquent public campaigner for action. LOE’s Steve Curwood has this remembrance.

CURWOOD: I first saw Stephen Schneider in action in 1997. Delegates from around the world had gathered in Germany to prepare for the upcoming Kyoto climate summit. The audience sat in rapt attention, as Professor Schneider delivered a riveting call-to-action, riffing from scientific fact to data set to policy analysis. He punctuated his speech with a laugh that slide easily into a smile- and then, without missing a beat- he turned serious--- demanding we focus on the profound implications of scientific studies.

Stephen Schneider. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

“Change our ways”, he warned, “before climate changes our ways in ways we will not like.” It was a passionate, virtuoso performance worthy of the Van Cliburn of climate change. Stephen Schneider’s perspective was philosophical and global and yet it was in his home state of California where he had perhaps his greatest impact. In his quest to save us from ourselves, one small step at a time---he helped persuade state officials to require more efficient refrigerators. Speaking to Living on Earth in 2005 Professor Schneider referred to the controversy over oil drilling in the Arctic Wildlife Refuge as he recalled the experience:

SCHNEIDER: Back in the '70s, in the energy crisis, California passed a rule fought and screamed at by the electric appliance industry requiring more than a factor of two, improvement in the efficiency of refrigerators. They said it would be too expensive and everybody's refrigerator would be too small. None of that happened. In fact the feds adopted those rules a few years later and the amount of the electricity that’s saved is so amazing that despite the Vice President telling us that energy efficiency is a moral virtue and doesn't do anything really and you need supply like ANWR, we have already saved just from refrigerators alone, from the initial California rules that went national, two ANWRs in energy, so there's a lot we can do.

Watch Schneider’s “Waking up to climate change” video

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZDSWpJeQ6Ns

(Embed code:

CURWOOD: Stephen Schneider did a lot. Trained as a biologist, he received a MacArthur “genius” award, shared the Nobel Peace Prize with other UN climate researchers and Al Gore, and published more than 450 scientific papers. Among his books: Science as a Contact Sport- he never shied from controversy- and The Patient from Hell in which he confronts his struggle with a rare form of cancer and global climate change. “In both cases”, he wrote, “there’s no room to be wrong.” In a recent interview he said, “I really trust this generation of kids to make a difference. I know we can invent our way out of some of the problem. What we have to do is convince the bulk of the public……My fear is that it's going to take a hurricane to take out Miami or fires in the West before they finally wake up. I just hope, said climate scientist Stephen Schneider, that it's milder crises sooner, and not more extreme events later.” He may be gone, but we’re listening Stephen Schneider… we’re listening.

Related link:

Stephen Schneider’s website

[MUSIC]: Van Cliburn/Kiril Kondrashin “Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto 1/Mvmt III” from Tchaikovsky Piano Conerto 1/Rachmaninoff Concerto 2 (RCA Red Seal 1987).

Beetle Ranching

Purple loosestrife in bloom. (Photo: NepRWA)

These Beetle nurseries are part of the purple loosestrife biocontrol project. Beetles breed on the covered Loosestrife plants and are later released into the wild. (Photo: NepRWA)

YOUNG: Asian Long-horned beetles, mountain pine beetles, emerald ash borer beetles – the names alone of these destructive, tree-chomping insects cause nature lovers to shudder. But some beetles might improve our landscape. Producer Emma Jacobs visited a group of Massachusetts volunteers who are raising beetles. It’s part of the effort to control a notorious invasive plant, purple loosestrife.

JACOBS: Purple loosestrife has beautiful purple flowers, but in most places in the US, it’s not a welcome sight. Once loosestrife gets into a wetland, it takes over, edging out native plants like cattails.

Volunteers at the office of the Neponset River Watershed Association help divide thousands of Galerucella beetles into small containers for distribution to Beetle ranchers. (Photo: Thomas Palmer)

ROCKLEN: We’re walking through a meadow. ...

JACOBS: On a warm afternoon, Carly Rocklen heads down a slope of thick grass to a low-lying depression filled with plants. In waist-high fishing boots, she wades through water about a food and a half deep towards the center of the wet meadow.

ROCKLEN: When we first started, this was basically all pink with flowers. So look all the way back, and you can see the purple loosestrife extends towards the treeline.

[SFX: Going through grass & bird noises]

JACOBS: Rocklen is a conservationist with the Naponset River Watershed Association South of Boston. Massachusetts is one of 49 states whose wetlands have been consumed by loosestrife. The plant invades some 300,000 acres in the U.S. each year. That’s just under the size of greater Los Angeles. Scientists have been hard at work developing tools to combat the fast-spreading invasive.

Reporter Emma Jacobs (left) and conservationist Carly Rocklen at the Neponset River Watershed Association office.(NepRWA)

ROCKLEN It’s far easier to see a variety of plants now than it was several years ago when most of what we were seeing was purple loosestrife.

[SFX: Ambi moving through grass/water.]

ROCKLEN: Ok, so this is interesting.

JACOBS: Rocklen waves me over to a thick, knee high stalk to see evidence of the secret weapon in her fight to bring the loosestrife down.

ROCKLEN: Here’s the purple loosestrife plant. You can see that it’s been fed upon by the galerucella beetles by all the holes in the plant. And you can see that there are galerucella eggs right here.

Beetle Rancher Niels Krejci found these eggs on the Purple loosestrife plants he is raising as part of a Purple loosestrife biocontrol / wetland restoration project in the Neponset River Watershed. (Photo: Niels Krejci)

JACOBS: Galarucella beetles come from Europe where the plant also came from in the 1800s. Scientists discovered that galerucella beetles eat only loosestrife and they were approved as a control organism in the U.S. in the early 1990’s. Beetles have since been released in about 35 states. Georgeanne Keer is a project manger for the Massachusetts State Division of Ecological Restoration. She says the introduction was necessary because, in the U.S., purple loosestrife has no natural predators.

KEER: It’s here and there is nothing in our environment that’s controlling it. And so we needed to find something that would actually keep it in check so that the other species can regain the competitive edge.

JACOBS: Keer oversees the release of Galerucella beetles in Massachusetts. The insects have been sought after by conservation groups around the country since their introduction.

KEER: There’s a high competition for beetles so again, the need to identify another source and so ranching or rearing, albeit a quirky term, became an option or another resource or tool.

Poking air holes so the beetles can breathe.

(NepRWA)

[SFX: Ambi office noise, copier, chatter]

JACOBS: In a small office kitchen, a group of women meet to divide up Carly Rocklen’s small purchased supply of beetles, which arrived overnight FedEx from New Jersey. These volunteer ranchers will raise thousands of beetles to release in Boston-area treatment sites over the season. One of the volunteers taps a pitcher to knock beetles into plastic cups.

JACOBS: The beetles are about 3 MM long and translucent. The insects have been refrigerated, which slows them down, but as they warm up, they start to take off.

Purple loosestrife in bloom. (Photo: NepRWA)

ANDERSON: Wait! Put him in here. Oh! Too late, he flew away.

[SFX: Fade in tapping, counting noises]

JACOBS: This is Janet Anderson’s second year raising beetles.

ANDERSON: I remember walking around as a girl with my mother in wetlands and seeing marsh marigolds and cardinal flower and things you just don’t ever see now. It was enormously frustrating that there was nothing we could do about it. And when we heard about this project it was just a no brainer to get involved.

[SFX: passing car]

JACOBS: A few weeks later I drove to Anderson’s home, where she and her daughter, Elizabeth, tend their beetles. The two show me a blue plastic pool of plants at the end of the driveway.

E. ANDERSON: This was actually my brother’s wading pool. It’s filled with a half dozen potted purple loosestrife stalks wrapped in mosquito nets.

J. ANDERSON Inside the netting are 12 to 15 beetles that we released in each plant. And the idea is to have the beetles mate and lay eggs and reproduce so that we have thousands by the end of the summer.

[SFX: Walking through marsh noises]

JACOBS: We walk to a marsh beside their home. They say there’s less loosestrife here. It could be because of beetles released last year.

ANDERSON: This right here is a clump of blue flag, which is a wild iris. If you look at these little brown tips these were all flowers a week or two ago. In the past the loosestrife shaded it so much that it was not able to bloom. So it’s nice to see that the native plants are already doing better.

JACOBS: Janet and Elizabeth Anderson and the other Boston-area ranchers, will soon release their beetles. The bugs will overwinter and be joined by additional beetles released next summer.

[SFX: Outdoor noise fade out underneath:]

JACOBS: For LOE, I’m Emma Jacobs.

Related links:

- The Neponset River Watershed Association

- Purple Loosestrife info – USDA site

[SFX: Birds, outdoor ambi]

[MUSIC]: Los Cincos “Dance Of The Japanese Beetle Bug” from Experimental Procedures in High Fidelity (Sympathy For The Record Industry Records).

Recipe for Raising Chickens

Mrs. Lovgreen dictated her life story and secrets on raising chickens to Nancy Rekow, our interview guest. (Photo: Nancy Rekow, NW Trillium Press)

YOUNG: Backyard chicken ranching is enjoying a revival as more people want more fresh, local food. And that’s bringing fresh attention to a 36-page, 35-year-old booklet from Bainbridge Island, Washington. It’s called “Recipe for Raising Chickens”. It was compiled by Nancy Rekow, who recorded the life and lessons of her neighbor, Minnie Rose Lovgreen. Lovgreen had nearly 80-years of experience raising chickens – and an amazing life story that Rekow details in a new book called, “Far As I Can Remember”. Nancy Rekow, thank you for making time for us today.

REKOW: My pleasure.

YOUNG: Where did the idea come from for this book?

REKOW: Well, partly from me and partly from Minnie Rose Lovgreen. She had always wanted to write a book about how to raise chickens. She was an expert, people were always phoning her for advice. And then in 1975 when she was 86 years old she was diagnosed with cancer. So I took my tape recorder into the hospital and said “Ok Minnie Rose, now we’re going to start your book.” We continued on because we had fun doing all that and I tape recorded her whole life story.

A girl with chicks from the National Archives, circa 1970’s. (Photo: flickr, Creative Commons).

YOUNG: Well, give me some examples of what it is Minnie rose knew about raising chickens that other people didn’t.

REKOW: Well, she knew secrets and she had probably raised chickens for 80 years or so and she always had her ears open and eyes open and studied everything around her. So she observed things about the chickens that nobody else knew. I can read you a little section here from page 7 of the book.

“If you peek at a setting hen she says quark, quark, quark in a deep ugly voice to say, ‘don’t bother me.’ She’s very protective when she’s setting. The person should wear gloves to reach in there because the hen will peck. Her beak is like a hard little fish hook….”

“The day before her babies hatch she doesn’t go off the nest at all. She stays right on it. Say about the 18th day, the baby chick is picking at the shell, trying to make a hole to get out. It peeps, and her mother puts her head under and talks to it, even in the shell. She says, in a deep tone, quirk, quirk, quirk. As much as saying hush, everything will be alright.”

YOUNG: It sounds to me like she had a naturalist’s eye for details that were important.

REKOW: Absolutely and of course she loved nature. She knew all sorts of secret things about chickens and other animals and farms, and she’d run a dairy farm for 30 years. But also she knew all sorts of things about flowers and gardening.

Minnie Rose Lovgreen lived and raised chickens on this dairy farm on Bainbridge Island in Washington State, until her death in 1975. (Photo: Nancy Rekow, NW Trillium Press)

YOUNG: And so you were visiting her with a tape recorder in the hospital…

REKOW: Yes.

YOUNG: Let’s hear a bit of that tape. This is her explaining how you can get more chickens by sneaking a few chicks in under a roosting hen.

LOVGREEN: If we buy more chickens to put under her, she can cover more chickens because her wingspan spreads out and she can get. And she can even cover 6 more than she could hatch out. That’s an economical way to build up your flock quicker.

YOUNG: So it was a lot of practical advice like that that she’s passing on to you, but while you’re talking to her… she’s on her deathbed.

REKOW: Right.

YOUNG: What were those conversations like?

Mrs. Lovgreen dictated her life story and secrets on raising chickens to Nancy Rekow, our interview guest. (Photo: Nancy Rekow, NW Trillium Press)

REKOW: When I first went into the hospital they had drugged her because they were testing. So her voice was a little faint. But as you listen to the tapes, the voice gets stronger and she was having a great time telling these stories. She knew she’d be sharing all her chicken raising advice with many people, although of course she didn’t know that, well by this time it was 24,000 books sold. But she knew her advice really worked. She loved connecting with people, she loved story telling. And she had her own language. She’d grown up in England and didn’t have very much education but picked up all these story-telling skills along the way.

YOUNG: And you also learned about her really remarkable life.

REKOW: Oh, absolutely.

YOUNG: I mean the fact that she made it across the Atlantic in the first place is pretty astounding.

REKOW: Uh, yes…. because she and her brother, who decided to come to Canada to, as she said, “go ahead better,” they purchased tickets on the Titanic. And then when they got to the docks the Titanic’s sailing was delayed for two weeks. She said, let’s go down and to the docks and see if there’s another ship leaving sooner. And there was, and they turned in their Titanic tickets and came on the other ship. And that’s a great gift because we end up with these 2 wonderful books and of course she ended up with a whole life.

YOUNG: A fateful decision right there.

REKOW: Right.

YOUNG: And here’s another excerpt from the tape recordings where she’s explaining how they ended up with a dairy farm. And, basically, she took charge of that situation. Here’s how she described that:

LOVGREEN: We told the old gentleman that we wanted to rent his dairy, Mr. Steiger. We wanted to rent his dairy and he said, you were here yesterday and you changed your minds. He said, I don’t think you’ve got enough backbone.

REKOW: [laughing] That was the right thing to say to you!

LOVGREEN: He said, “I don’t think you’ve got enough backbone” and I said, “Well I’m renting it this time.” He said, “You’re renting it?” I said, “Yes I’m renting it. And here’s the deposit.”

REKOW: And that’s a wonderful example of her spirit. Of course by that time she was, what 30 or something, and had had years of experience in solving problems and in inventing creative ways out of situations or into situations. And she had her mind made up that they could have a dairy farm.

YOUNG: And she seems pretty headstrong, and in a way, kind of ahead of her time, as a woman making decisions and taking action.

REKOW: Absolutely, all her life she’d been like that. She was a problem-solver, and yet not in a nasty way, not in an obnoxious, bossy sort of way, although she was rather bossy sometimes, but she explored and thought about it and thought her way through to solutions.

YOUNG: Did Minnie Rose live to see the book?

Minnie Rose Lovgreen’s book: “Recipe for Raising Chickens,” has sold over 24,000 copies since 1975, and is it’s 3rd edition. (Photo: Nancy Rekow, NW Trillium Press)

REKOW: Oh yes, she did get to see the chicken book published. So she had the great joy of knowing that her chicken raising advice was reaching thousands of people. People ask me, would Minnie Rose have been astonished that her book is still selling? And I always say, well she would have been very pleased and proud. But the thing is, she knew her advice really worked! [laughs] And so the whole thing has been a miracle and we never know in life when we meet somebody or things come together and we never know at the time what’s going to come out of that.

YOUNG: Well, you know, to me that is kind of the take away lesson from the book and hearing you talk about how this came about is…this happened because you took an interest in your neighbor and bothered to really listen to her.

REKOW: That’s really true, and yes we follow what intrigues us and if we’re fortunate amazing things happen.

YOUNG: Nancy Rekow, who helped make Minnie Rose Lovgreen recipe for raising chickens possible, thank you very much.

REKOW: Thank you very much, and now when you decide to raise chickens you’ll be all set!

Related link:

Read more about Minnie Rose Lovgreen's “Recipe for Raising Chickens"

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth hormones on their cows. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners. The Ford Foundation, The Town Creek Foundation, The Oak Foundation—supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues. And Pax World Mutual Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at Pax world dot com. Pax World for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI – Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth