September 17, 2010

Air Date: September 17, 2010

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Inspectors give the Low Down on Food Safety

View the page for this story

Recent recalls have put a spotlight on the agencies that are in charge of our food safety: the FDA and the USDA. Host Jeff Young talks with Francesca Grifo, director of the Scientific Integrity Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Her organization surveyed employees in these two agencies and found some revealing information about our food system. (06:30)

Mid-turmoil on Climate

View the page for this story

Primary upset victories have brought a wave of conservative candidates dismissive of climate change a step closer to Congress. Some are skeptical of climate change science while others attack the proposed policy solutions. Host Jeff Young talks with Washington correspondent Mitra Taj about what the changing political climate could mean for efforts to curb carbon pollution next legislative session. (05:30)

Future Food: Frankenfish

View the page for this story

American consumers eat genetically engineered plants, like corn and soybeans, and soon, we could also be eating genetically modified animals. Ron Stotish, director of AquaBounty, tells host Jeff Young about the development of his company’s engineered salmon. Stotish also describes the FDA’s approval process and discusses the issue of mandatory labeling. (06:45)

Fishy Tale

/ Paul GreenbergView the page for this story

The Food and Drug Administration is poised to make a decision about whether to allow genetically modified salmon in the marketplace. Paul Greenberg, author of the new book "Four Fish," says it's one of many decisions the government has to make about the future of salmon that will have a huge effect on our environment and our last wild food. (03:00)

The Search For Missing Frogs

View the page for this story

Roughly a third of all amphibians are at risk of extinction. Scientists don't know what species still exist and which need better protection. Over the next year and a half, a team of researchers will travel to 20 different countries in search of frog species that haven't been seen for at least a decade. Conservation International herpetologist Robin Moore tells host Jeff Young about some of the unusual species of missing frogs. (08:15)

Courageous Sailing

/ Amie NinhView the page for this story

At the Boston nonprofit Courageous Sailing, urban kids spend their days learning in a classroom on the sea. For more than two decades, the organization has strived to turn a historically elite, white sport into an activity that transcends both race and class. Planet Harmony’s Amie Ninh reports. (06:15)

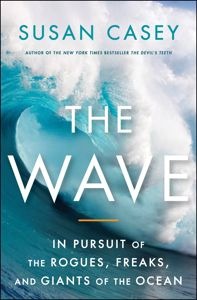

The Wave

View the page for this story

Giant waves are both fearsome and awesome. Author Susan Casey speaks with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood about her new book, “The Wave: In Pursuit of the Rogues, Freaks, and Giants of the Ocean”. The book follows big wave surfers, mariners and scientists who have encountered huge waves and have lived to tell the tale. (08:55)

BirdNote ® - Shorebirds on the Wing

View the page for this story

At this time of year, millions of shorebirds, including sandpipers and plovers, are migrating south for the winter. And, as this BirdNote ® explains, some of these frequent fliers travel great distances to escape the cold. (01:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Jeff Young, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Francesca Grifo, Ron Stotish, Paul Greenberg, Robin Moore, Susan Casey

REPORTERS: Mitra Taj, Amie Ninh

[THEME]

YOUNG: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

YOUNG: I’m Jeff Young. America’s food safety system comes under fire—from some of the people inside it. A survey of food inspectors finds political and corporate influence undermining food safety.

GRIFO: What we had were 330 respondents telling us that public health had been harmed by businesses withholding food safety information from agency investigators.

YOUNG: Also, the Food and Drug Administration considers approving the first food from a genetically modified animal. We learn more about transgenic salmon.

STOTISH: A single copy of the growth hormone gene from the Chinook salmon has been inserted into this Atlantic salmon genome. That extra copy basically confers the ability to grow more rapidly in that first year of life.

YOUNG: But critics want to stop what they call Frankenfish! Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth! Stick around.

Inspectors give the Low Down on Food Safety

USDA inspection of swine carcasses. (USDA.gov/Wikimedia Commons)

YOUNG: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. The recent massive recall of tainted eggs put food safety back on the front burner, and put some heat on Congress to consider a Food Safety bill that passed the house but languishes in the Senate.

A recent survey from the Union of Concerned Scientists added new voices to the debate: federal food safety workers. The UCS asked some seven thousand inspectors and scientists in the Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration how they rate the job they do. Francesca Grifo of the UCS says the survey found a lot of concern about political and corporate influence.

GRIFO: They told us a lot of things, but I think the big picture piece was that, you know, we have a food safety system that is trying to do the right thing, and we have a lot of really good people out there trying. But, we also have a system where special interests and political interferences- it’s just too easy for them to inhibit the ability of these agencies to protect our food.

Francesca Grifo, Senior Scientist and Director of the Scientific Integrity Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. (Photo: Union of Concerned Scientists)

YOUNG: Give me some specifics. What did your survey tell you about what workers at FDA and USDA think about political interference?

GRIFO: Well, we had 507 respondents tell us that they had personally experienced one or more incidents of political interference. Now, that’s not heard about, read about, thought about, that’s personally experienced. And that’s a very big number.

YOUNG: Well, what are we talking about when we say political interference? What might have happened there?

GRIFO: Many different things, but we’re talking about purposefully excluding or altering technical information or conclusions in an agency scientific document. It might also include experiencing selective or incomplete use of data- in other words- another word for this is cherry picking. So, going through and picking out the data that actually gives you the regulatory outcome that you’re after. Now what we’re talking about when we talk about political inference is not so much what the role of the science is in the decision making, but what happens to that science along the way as it goes from the scientists to the regulator or decision maker.

YOUNG: You also asked about the role of corporate influence. What did they tell you about that?

GRIFO: They told us a lot. We’re looking at big businesses withholding food safety information from agency investigators. Now, what does that mean? That means that when an inspector has a question about a piece of food, they go back to industry and say ‘hey, can you tell us where this came from? Can you tell us about the distribution network? Can you tell us any number of different things?” That in fact, instead of saying ‘wow, let us just open up these records so that we can get to this and make sure that the public is safe,’ in fact what we have were 330 respondents telling us that public health had been harmed by businesses withholding food safety information from agency investigators.

YOUNG: And what sort of time frame are we talking about here? Are these people talking about incidents from many years past or here recently?

GRIFO: We had both. We specifically wanted to tease that out because we were very interested in whether or not a change in administration had, in fact, changed the situation at these agencies. We did do a survey at FDA in 2006 and we are seeing incremental improvements. But, certainly, as long as we have 507 respondents personally experiencing one or more incidents of political interference, and that is within the past year, we still have a fairly big issue out there to tangle with.

YOUNG: I guess you also put in a share-your-thoughts section here. Give us a flavor of what the respondents had to say there.

GRIFO: They really came back to us with a lot, a lot of rich information. And, one of the ones that I really like is from a USDA employee who said ‘First of all, remove food safety inspection service from USDA. It’s like having the fox in charge of the hen house.

Any action we try to take has to pass industry scrutiny and the impact on the bottom line: inspectors in the field lose every time because the bureaucrats at district level and above will not support any action that goes against the wishes of the industry.’ I mean, that’s a hard position to be in, to be that employee who’s on the line and trying to get attention and interest for that.

YOUNG: What happens when one of these workers within the system speaks out and tries to correct the things they see going wrong?

GRIFO: You know, there are multiple whistle-blowers. I mean, that’s what we call somebody who really sees something wrong and tries to bring it to people’s attention. One who we’ve had particularly moving conversations with is a gentleman named Dean Wyatt who was a USDA veterinarian who oversaw federal slaughterhouse inspectors. He was not able to speak out about things he was seeing on the line about problems and issues that had direct relationships to people’s safety.

USDA inspection of swine carcasses. (USDA.gov/Wikimedia Commons)

YOUNG: So, based on what you’re hearing from the people who work in this system, in this survey, what political reforms would make our food safety system better?

GRIFO: You know, I think having the eyes and ears that are there on a daily basis able to speak out about it is critical. So, that’s whistle-blower protections. It’s also that the scientists looking at this need to be able to publish. And, you know, people like you need to be able to call them on the phone, talk to them, and have them not fear retaliation for speaking out. Right now it’s very difficult for them to do that. They’re the eyes and ears inside. We need to have a way for them to get that information outside.

YOUNG: How does what you’ve learned in the survey here pertain to the legislation that is pending on Capitol Hill in the Senate?

GRIFO: There are four major reforms in that legislation. One is, more authority for mandates for the food recalls, more resources to protect food safety. Right now, you know, those are a part of the bill. We need to make sure that we have more inspections and that we have inspections more often. Right now, those are part of the bill. We need to make sure that we really look at requiring food production facilities to conduct science-based hazard analysis. Right now, those are in these bills. So, we hope those pieces stay in those bills and we end up with a really strong piece of legislation that will allow Americans to get the protections they expect and deserve.

YOUNG: Francesca Grifo with the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks very much!

GRIFO: Thank you, take care.

Mid-turmoil on Climate

How green could the 112th Congress be? Primary results suggest dimming political interest in tackling climate change.

YOUNG: Latest reports from Capitol Hill say Oklahoma Republican Senator Tom Coburn has blocked the food safety bill. That essentially kills its chances at least until Congress returns after Election Day. Well, the rocky economy and the rise of the Tea Party are driving mid-term election campaigns. The primaries brought some stunning upsets and a lot of candidates who oppose action on climate change. Living on Earth’s Washington correspondent Mitra Taj joins us to talk about what the elections might mean for federal action to cap greenhouse gases. Hello, Mitra…

TAJ: Hi Jeff.

YOUNG: So Mitra, what’s the takeaway from the primary season when it comes to climate change?

TAJ: Well, I think we saw candidates very critical of legislative action on climate change win their party’s nomination. We saw that when Republican primary voters in Nevada and Alaska chose Tea Party supported candidates who had expressed doubts about the threat of climate change. And we saw it recently in Delaware in the Republican race for Senate when Christine O’Donnell beat nine-term Congressman Mike Castle.

YOUNG: Mike Castle, among just eight Republicans in the House to vote for the cap and trade climate bill there…How did that play out in the campaign for Senate in Delaware?

TAJ: So O’Donnell really seized his ‘yes’ vote as an opportunity. She repeatedly attacked cap and trade and Castle’s support of it. And made very clear how she would have voted.

O’DONNELL: I believe cap and trade is one of the most destructive pieces of legislation in American history. That will push us much more toward socialism than ever before, if not, be the final nail in the coffin that makes America a socialist society.

TAJ: Now, the Democrat she faces in the general election, Chris Koons, says he’s in favor of a cap and trade solution to climate change. Which is interesting because, you know, cap and trade really emerged as a Republican policy tool under the first Bush administration-- a sort of market-based alternative to traditional environmental regulation. But if you look at the crop of Republicans running for office this year, it’s hard to find any who’ve expressed support for it.

YOUNG: Is it just cap and trade that they’re against?

TAJ: Actually several of these Republican candidates have gone a step further and are actually questioning the science of climate change, not just the policy proposals to solve it.

YOUNG: So, I noticed Christine O’Donnell and a lot of the Republican candidates have signed on to something that’s called the ‘no climate tax pledge.’ What’s that all about?

TAJ: That’s a pledge to taxpayers that says basically ‘I’ll oppose any climate change legislation that increases government revenues.’ And, so far, some six hundred politicians have signed onto the pledge. And the group behind it, Americans for Prosperity, is funded by David and Charles Koch, two brothers who run a big petrochemical conglomerate called Koch Industries. And, they’ve been very active in supporting the Tea Party movement and also in funding opposition to environmental regulations. The green group Greenpeace reports that Koch has spent fifty million dollars to help kill regulations on green house gasses. And, Koch industry’s response is that it’s just promoting economic and intellectual freedom and not opposing any particular piece of legislation.

YOUNG: So, what are we seeing happening on the Democrat’s side when it comes to climate change so far in the elections?

Coal supporters rallied Congress to oppose regulations to curb carbon pollution. (Photo: FACES of Coal)

TAJ: Many Democrats who face serious challenges from Republicans are pretty cautious about voicing public support for climate action, especially those from states with strong ties to fossil fuels. Just recent a few showed up at a coal rally on Capitol Hill organized by a pro-industry group that flew in coal supporters from Appalachia.

[RALLY NOISES: Be proud to be a coal miner. Stand up for coal mining. Whose jobs? Our jobs! Whose coal? Our coal! Whose children…?]

TAJ: And at the rally a number of prominent lawmakers climbed on stage to profess their love for coal. Including West Virginia governor Joe Mansion, the Democrat running against John Lacey for the Senate seat left open when Robert Bird passed away. And, Masion’s trying really hard to out-coal his opponent, as you can hear here:

MANSION: President Obama is wrong on cap and trade. Lisa Jackson is wrong with the EPA attacking the energy that fuels America.

YOUNG: Well, it sounds like governor Mansion there is going after EPA for using their authority under the Clean Air Act to try to regulate greenhouse gasses.

TAJ: Ever since climate legislation got stuck in the Senate, the EPA’s authority to act has been the central climate change battle. Legislators from both sides of the isle have been trying to keep the agency from writing new rules that would curb emission from power plants and refineries. So, this could be really what’s at stake in the new Congress.

Mike Castle, one of Congress' few Republican supporters of climate change legislation, recently lost the Delaware primary election to a fierce opponent of cap-and-trade. (U.S. House of Representatives)

YOUNG: Mitra, the Tea Party upsets have really been the big story so far out of the primary elections. What have we learned about the Tea Party when it comes to the environment-- where they stand on the environment and what this movement might mean for the environment?

TAJ: It’s still really unclear. They’ve been really hard to pin down on a lot of issues, including the environment. I think we tend to think that they’re not too interested in environmental protection, but a poll from earlier this summer found that actually more Tea Party supporters favor comprehensive climate change legislation than oppose it. So they’re far from being a monolith ideologically.

YOUNG: And the big question, of course, what does this new political climate mean for action on climate change?

TAJ: Well, I guess we’ll have to see what happens in the general elections. A lot of analysts think that the really conservative candidates like Christine O’Donnell could end up delivering even more votes to Democrats, so that in turn, could mean more votes for addressing climate change. But, I think, given the kind of rhetoric that survived the primaries, it might be really hard for politicians, especially Republicans, to conclude that climate action is the popular thing to do right now.

YOUNG: Mitra Taj is Living on Earth’s Washington correspondent. Thanks, Mitra!

TAJ: Thank you Jeff.

[MUSIC: Jamiroquai “Main Vein” from A Funk Odyssey (Sony Music 2001)]

YOUNG: In a moment, genetically modified fish – is it Frankenfood or a practical answer to the planet’s protein appetite? Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[MUSIC: The Rhythm Section: “Waiting For The Sun” from The Best Of Cookin (Ubiquity Records 2000)]

Future Food: Frankenfish

An AquaBounty salmon in the background and a traditional salmon in the foreground. (Photo: AquaBounty)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. The Food and Drug Administration is considering approval of the first genetically modified animal for human consumption. It’s a fish— a farm raised Atlantic salmon carrying a gene and gene marker from two other fish species. The Massachusetts-based company Aquabounty says food from its fish is no different than food from other Atlantic salmon. The FDA’s initial findings seem to agree with the company, which calls the new fish the AquAdvantage Salmon.

Some environmental and fisheries groups have other names for it: They call it “Frankenfish” and “mutant” in a campaign to block FDA approval. These groups say the fish could have profound unintended effects on wild fish and could open the regulatory doors to approval for other genetically altered animals. Ron Stotish is Aquabounty’s president and CEO. He came by our studio to answer those criticisms and to tell us just what his company’s new fish is.

STOTISH: Well this is an Atlantic Salmon first and foremost and, what has been done is a single copy of the growth hormone gene from the Chinook salmon has been inserted into this Atlantic salmon genome. So, it has the normal resident Atlantic salmon growth hormone and it also has this extra copy. That extra copy basically confers the rapid growth phenotype, or the ability to grow more rapidly in that first year of life.

A drawing of an Atlantic Salmon in the wild. (Drawing: Timothy Knepp)

YOUNG: How much faster?

STOTISH: The most easily measured, or the most easily described endpoint is that it will reach market weight in about half the time.

YOUNG: And, it’s more tolerant to cold? Do I understand that correctly?

STOTISH: No, not really. The confusion on that was because the promoter, if you will, the on-off switch for the gene, is from a cold-water fish called the Ocean Pout. That is simply a regulatory element and simply allows the gene to be transcribed into the protein the growth hormone.

YOUNG: Now, why do we need a genetically altered salmon?

STOTISH: Well, the fish was originally developed as a faster growing production tool for the salmon industry. However, as we developed the technology we realized that this technology could be adapted to allow other production systems- it could be land based- that have the potential to reduce transportation costs, reduce the carbon footprint of transportation of large quantities of salmon. And, basically be a sustainable method of production of a safe and readily available seafood product.

YOUNG: Because this is land-based aquaculture that you want this to be applied to, what does that mean for our long-term view of how we’re going to produce our fish?

STOTISH: Well, if you consider the trout industry, for instance, trout are already produced in primarily land-based contained systems. The systems used for AquaAdvantage fish would not be remarkably different from those in principle, perhaps more sophisticated. So, what does it mean? It means if you were able to grow salmon economically in land-based systems, closer to population centers, you could probably create jobs in the Unites States, you could probably grow seafood closer to population centers.

And the net result would be a reduction of transportation costs, a reduction of the carbon footprint, and perhaps most importantly, a safe and sustainable high quality seafood product, closer to the population centers where consumption occurs.

YOUNG: That’s a good argument for land-based aquaculture, but why is that an argument for a genetically modified fish?

STOTISH: Because salmon, particularly in their first year of life, grow very slowly. The benefit of a more rapidly-growing fish which is slightly more efficient, reducing the cycle times, and reducing the time required to maturation, significantly alters those economics, making this a safe and sustainable alternative.

YOUNG: So, as a consumer, would I know if you get approval, that I’m buying a genetically modified animal?

STOTISH: Under the current US labeling policy and laws, the use of a label for a material that is not materially different, or not different in any significant aspect is not necessary. And, in fact, might be false and misleading. So…

YOUNG: How would it be false and misleading?

STOTISH: Well, you’re indicating perhaps a difference that isn’t there. If it is equivalent to the traditional food, there is no material difference. Then, there really isn’t any basis for a label. A label for instance, for mode of production. We don’t label other commodities for different modes of production.

YOUNG: Well, sure we do. We have farm-raised versus wild-caught, for example.

STOTISH: Well, you can, and that’s voluntary labeling, and voluntary labeling is still legal under the law. But, I think what you’re referring to is special labeling, required labeling, indicating that this is, for instance, produced using a transgenic technology. But, the difficulty in required labeling and segregation of the product, we think would probably be an adequate barrier that it would kill the product and never give it a chance to even be tested.

YOUNG: What do you make of the opposition to approval of your product? This coalition of some thirty groups, some environmental groups, some groups that represent fishermen… What do you make of their opposition which is primarily around environmental concerns, that if your fish gets out there it might cause problems?

STOTISH: Many of the concerns that are being raised out there today ignore the information that’s already out there in the public domain in terms of the sterility of the fish, the mono-sex female nature of the fish, and the fact that there’s redundant biological, physical containment for these fish. So, any salmon producer who produces the egg, must have their facility inspected by the FDA, prior to being able to receive those eggs, and a part of that inspection will also include the preparation of an environmental assessment.

There are people who are opposed because they see this production paradigm as a possible commercial threat to their product. So, the opposition comes in many forms, much of it in misunderstanding, much of it, also, vehemently opposed to new technology, and particularly, technologies that may be based in genetic modifications.

The genetically modified AquaAdvantage salmon (background) dwarfs an Atlantic salmon of the same age. (Photo: AquaBounty)

YOUNG: Because this could be the first, does that put an extra burden on you or on this decision making process? Because, in all likelihood, there are other companies with other genetically modified animals that would likely follow in your footsteps, finsteps, whatever it might be here?

STOTISH: (Laughs.) Of course it does. There’s always a challenge with being a pioneer, there’s a significant burden that goes along with it. It would be stating the obvious that we’ve attracted the attention of everyone who is opposed to this technology for whatever reason, and have become sort of a lightning rod for the technology.

YOUNG: So, what’s your hunch? Is this going to be, pretty soon, a common product?

STOTISH: Well, if you read the reviews and the decisions from the review group, you would hope that this product will be approved and will be entered into commerce.

YOUNG: And, how is it? Have you tried it?

STOTISH: It’s wonderful! It’s exactly the same as a high quality Atlantic salmon.

YOUNG: Ron Stotish with Aquabounty, thanks for coming by.

STOTISH: Thank you very much.

YOUNG: Aquabounty is also seeking approval to sell their genetically modified salmon in other countries. There’s a lot more on this at our website L-O-E dot ORG. and share your thoughts at our Facebook page; it’s PRI’s Living on Earth.

Related links:

- Visit AquaBounty’s website

- Read a Washington Post article about the FDA considering the approval of genetically modified salmon for human consumption

Fishy Tale

.jpg)

Paul Greenberg with a wild Alaskan King Salmon. (Photo: Jon Rowley)

YOUNG: Well, obviously Ron Stotish has his own fish to fry in this case. But whether or not consumers find the whole idea of genetic modification palatable is a whole other kettle of fish. Paul Greenburg wrote the new book “Four Fish,” which tells the story of salmon, tuna, bass and cod, and our reliance on them as food. He has something else on his plate.

GREENBERG: So, Uncle Sam walks into a fish restaurant, takes off his star-spangled hat, and asks the waiter what’s on special.

“Uh, today we have a genetically-modified Atlantic salmon, spliced with Pacific salmon growth gene and modulated by a regulator protein from an Ocean Pout.”

"Uh, ok, anything else?"

“Not much, I’m afraid, just a wild Sockeye from the pristine unpolluted waters of Bristol Bay, Alaska. What’ll it be?”

If you were in Uncle Sam’s seat, you’d surely chose the wild salmon over the modified one, but our government, forever at odds with itself when it comes to figuring out the puzzle of the American seafood supply, is leaning towards the transgenic. At this very moment, the US Food and Drug Administration is close to approving an engineered Atlantic salmon that grows twice as fast as an unmodified fish. If North America’s existing salmon farms all switch to growing modified animals, we could have about a quarter billion more pounds of salmon in the market every year.

Sounds good on the surface, but seen in the larger context of American fisheries, it doesn’t make much sense. While the government seeks to boost farmed salmon supplies through transgenics, it is simultaneously letting wild salmon go to pot. At the headwaters of Bristol Bay, Alaska, the spawning grounds of perhaps the most productive wild salmon runs left on earth, the international mining giant, Anglo American plans to construct pebble mine. The largest open pit copper and gold mine in the US. Mines of this nature are notoriously bad for fish. Just this summer, a copper mine failure in China’s Ting River killed millions of fish. A similar disaster in the Bristol Bay fishery could mean the destruction of around a quarter of a billion pounds of fish.

Paul Greenberg with a wild Alaskan King Salmon. (Photo: Jon Rowley)

Precariously, about the same amount of salmon that Aquabounty hopes to produce with its transgenic fish. US Environmental Protection Agency has the power to stop Pebble Mine through the Clean Water Act, but has so far failed to act. More transgenic fish, less wild fish. You have to scratch your head at a government that’s planning that kind of seafood menu for it’s citizens. Instead of endorsing a risky experiment in genetic salmon modification, wouldn’t it be better if our leaders protected wild salmon habitat? In the end, we’d have just as much fish on our plates, and a safer environment to boot. Personally, I’d hate to go into a restaurant and have a transgenic fish be the only salmon option on the menu. If that ends up being the case, I might just order the chicken.

YOUNG: Paul Greenberg is the author of Four Fish: The Future of the Last Wild Food.

Related links:

- 2010 Bristol Bay Sockeye Salmon Forecast

- World Salmon Production and Consumption from WWF report "The Great Salmon Run"

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck & new Grass Revival “Jalmon With Salmon” from Deviation (Rounder Records 1984)]

The Search For Missing Frogs

The Mesopotamian Beaked Toad hasn’t been seen since 1914. Scientists only have this artist’s rendition to go on. (© Paula Andrea Romero Ardila)

YOUNG: You may have heard about a newly discovered species of frog called a micro frog. It’s about the size of a pea. It was discovered living inside pitcher plants in Borneo by a team of scientists searching the world for lost amphibians. Over the next year and a half they’ll travel to 20 countries in search of more than 40 species no one has seen in more than a decade. Robin Moore is one of the Conservation International herpetologists getting ready for one of these rugged trips.

MOORE: My first expedition will be to Colombia in the mountains, very remote forests, we’ll probably be hiking for about five hours to get to the localities that we need to get to. We’re going to be searching for four species, the most interesting species to me, I think, is the Mesopotamia Beaked Toad, and it hasn’t been seen since 1914. All we have is an artist’s rendition of the species. If we do find this, we’ll be able to capture the first photos of this, the first video. To me, it’s going to be an exciting search!

YOUNG: How do you even know where to look? I mean, if all you have to go on is an artist’s drawing from 95 years ago?

MOORE: Yeah, it’s a tricky one. We also believe that this toad doesn’t need water to breed. So, it probably lays eggs, which hatch directly into toadlets. So, that also makes it tricky because we can’t rely it being in or around water. So basically, it could be anywhere in the forest. And, it’s designed to look like a leaf; it’s designed to be camouflaged and to hide. So, the fact it hasn’t been seen for 96 years definitely suggests that it’s good at not being found.

YOUNG: (Laughs.)

MOORE: We’re going to try and thwart it.

YOUNG: Well, lets say that you get lucky, and you do find one of these, well, then what?

MOORE: The next step if we do find one of these is to determine whether the species is doing ok, whether it’s threatened, whether the habitat its in needs protection, and also to highlight the species as a flagship species for conservation.

YOUNG: And, we have a recording, I think, of one of the frogs that you’re going to be looking for. This is the sharp-snouted day frog. Let’s listen to a bit of that.

Atelopus sorianoi. (Photo: © Enrique La Marca)

[SHARP-SNOUTED DAY FROG SOUNDS]

MOORE: This is a species from Northeast Australia, from Queensland. Since 1994, only three individuals have ever been seen, and the last one was spotted around 1997. It’s believed to have possibly gone extinct as a result of a disease, which has been spreading around the world, and has really impacted a lot of amphibians. And, it lives in a region, which has been affected by this fungus, which is why we think it could have succumbed. But, you know, you just never know.

YOUNG: How is that fungus spreading?

MOORE: The mechanism by which it’s spreading is largely a mystery. There’s some theories that it originated in Africa. The earliest known record is from an African frog, the African Clawed Frog, which is actually, used to be used for pregnancy testing in people. So it was transported around the world, which would have been one way that it spread. In other instances, it shows up in places where we don’t really know how it got there. You know, maybe it traveled there on the leg of a bird, or an insect. There’s so many ways that it could enter an area that we’re still getting a grasp on exactly how this fungus works, how it moves. At the same time, it’s absent from some areas where we would expect it to occur. Madagascar seems to be free from the fungus.

YOUNG: You know, just looking down the list of some of the animals here, the names alone are so evocative. The Venezuelan Skunk Frog, Schneider’s Banana Frog, Gastric Brooding Frog…. Where do these names come from?

MOORE: The common name is usually a local name that’s been given to the frog depending on appearance or behavior. The Gastric Brooding Frog is one of the most interesting ones. What they do is when they lay their eggs, the female actually takes the eggs, ingests them into her stomach. She turns off her digestive juices, and the eggs develop into tadpoles and actually develop all the way into small froglets in the stomach. And then she gives birth to fully formed frogs out of her mouth.

The Sharp Snouted Day Frog hasn’t been seen in its native Australia since the late 1990’s. (Conservation International)

YOUNG: That’s amazing!

MOORE: This to me, would be a phenomenal finding. It hasn’t been seen since the mid ‘80s and with its disappearance really went the opportunity to do research into what exactly is happening here with the brooding. There have been suggestions that we could have learned a lot about mechanisms for turning off the digestive juices that could have helped us control things like stomach ulcers.

YOUNG: Well I guess that points to the larger question about…why do this? I mean, why go to the jungles of Colombia and these far flung places, which can’t be easy, why is this important?

MOORE: Yeah, it’s a good question. Yeah, it’s certainly not easy. Hearing back from some of our search teams who have already started going into the field about land, mudslides and heavy rains. You’re really up against the elements when you’re out there, and it’s not easy. I think that this important because we’ve known for a while that amphibians are not doing well. We know that a third are threatened with extinction, and there are many species that we suspect have gone extinct.

And, I think, to loose a third of an entire class that’s around 2,000 species, would have devastating consequences. Amphibians play a number of vital roles. First of all they feed on insects, such as crop pests and disease vectors, so mosquitoes, which carry malaria. And they also, play a very important role in cycling nutrients. They form a link between the aquatic and terrestrial environments. So, if you remove an amphibian from the system, it’s also like losing two species because very often you’re removing the tadpoles which are regulating the nutrients in streams. They’re keeping the streams clean, they’re eating the algae.

And you’re also removing the adults, which are feeding on the invertebrates, the insects in the forest, and helping recycle leaves back into the system. So if you remove amphibians, we really don’t know what the cascading impacts will be. And personally, I don’t really want to find out the hard way. Because, once we lose these, we can’t bring them back.

YOUNG: Here we are watching this mass extinction most of us are aware of this, I think, to some degree…and yet, not doing much about it, for the most part. Kind of reminds me of the old song about putting a frog in a pot of water and slowly raising the heat.

The Mesopotamian Beaked Toad hasn’t been seen since 1914. Scientists only have this artist’s rendition to go on. (© Paula Andrea Romero Ardila)

MOORE: It’s hard sometimes for people to really relate to something that’s so removed from their everyday life. And, I think, one of the things that we wanted to achieve with this campaign is to engage people. You know, I know the list is depressing, when you think these haven’t been seen for along time. But we’re hoping that by finding some of these, that we’ll also have some good news stories that will allow us to show that there is still hope. There is still a lot out there worth saving and I think tapping into that sense of exploration and discovery is something that we need to do to really help to connect people with the world around us.

YOUNG: Robin Moore is a herpetologist and amphibians’ conservation officer for Conservation International. Thank you very much!

MOORE: Thank you!

YOUNG: And, hey- if you happen to find the Mesopotamian Beaked Toad, you’ll let us know, right?

MOORE: I will do, I will do. I hope we can report some good news.

Frog Talk- Conservation International scientists talk about why they like frogs.

Related link:

Conservation International Search for Lost Frogs

[MUSIC: Sonny Boy Williamson “Fattening Frogs For Snakes” from The Animals With Sonny Boy Williamson (Charly Records 2009)]

YOUNG: Just ahead, the upper crust sport of sailing finds some new fans--inner city kids. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

[MUSIC: Will Bernard: “Party Hats” from Party Hats (Palmetto Records 2007)]

Courageous Sailing

Kids at Camp Harbor View play a racing game on the waters. (Photo: Amie Ninh)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. Sailing has never been what you’d call a democratic sport. It conjures images of wealthy yacht clubs, blazers and topsiders. But a Boston nonprofit called Courageous Sailing wants to make sailors out of inner city kids-- and help them reconnect with the outdoors and learn to value the sea. For more than two decades, the organization has worked to turn the historically elite, white sport into an activity that transcends race and class. Planet Harmony’s Amie Ninh reports from Boston’s Charlestown Navy Yard.

[BOAT SOUNDS]

WOMAN: Ready to tack?

KIDS: Ready!

NINH: It’s a fairly windy day and that means conditions are just right for sailing. Kids, thrilled to be out on a 20-foot sailboat, tug on ropes to control which direction they’re heading.

WOMAN: Where do you want to go first? The Mystic or the Basin?

NINH: Here at Courageous Sailing Center, kids from all over the city get to experience what it’s like to be out on a boat.

GABRIELA: It’s kind of a once in a lifetime experience to just be out here in a boat all day. The experience is really good because I would have never done this because I just don’t live near water really.

NINH: 9-year-old Gabriela from the South End isn’t the only young sailor who may not realize the sea is actually in her backyard. More than 1,000 low-income Boston kids get the opportunity to sail for free through the organization. Kate Henderson directs the youth program and wants kids to reconnect to the city’s maritime past.

HENDERSON: And that’s what we try to do here, is to not only get them to try this sport, which is so foreign to them culturally a lot of the time, but also gets them exposed to an environment that unfortunately has become very foreign to them but is also very important for them to, I think, appreciate and interact with.

NINH: Henderson says diversity is one of the program’s strengths. More than half of the kids are African American or Latino.

HENDERSON: It’s interesting to hear that these kids learn from each other that though people may seem different on the surface, we’re all just people deep down. It really opens them up to new experiences, new people and making friendships with people unlike themselves. It makes them more open-minded.

NINH: Worlds apart from the bustling Charlestown Navy Yard are the scenic Boston Harbor Islands. The sailing program expanded three years ago to include kids at a summer day camp on one of the islands.

HENDERSON: One of the biggest, most challenging groups we’ve worked with is probably this group out at Camp Harbor View where literally kids felt like this was a white man’s sport and that going out on boats was just this silly, frivolous, you know, thing.

NINH: Camp Harbor View serves kids from at-risk neighborhoods and is run by the City of Boston and the Boys and Girls Club. Jennifer Toscano-Seibert directs this site.

TOSCANO-SEIBERT: This summer we’ve really seen a lot more Latino campers and a lot more campers of African American descent. It’s really exciting for us. There’s no reason the harbor should not be accessible to everyone who lives in Boston.

NINH: With sailing often come life lessons, at least that’s what 13-year-old Kristin from Dorchester found.

A youth helper from Save the Harbor/Save the Bay shows a camper how to determine acidity using pH paper. (Photo: Amie Ninh)

KRISTIN: I decided to do sailing because it’s something I’ve never tried before, and I was curious about it. I’ve learned that, don’t give up until you try one thing because when I first started sailing was kind of hard but now I get it. It’s tons of fun. I love learning how to steer the boat.

NINH: Now, sailing has become routine for the kids who go out on the boats each day at camp. But 14-year-old Terrell from Dorchester remembers his first outing.

TERRELL: Well, my first year here, I went sailing and the sailing instructor tipped the boat and I got, very, very scared, like everything was just falling down this way. So then I started to cry because I was very scared. I thought the boat was going to tip over. So I had to go back in the motorboat and wait at the dock.

NINH: What a difference three years make.

TERRELL: I’m used to the tipping, and it’s not so scary anymore. And I hope to sail to many places.

NINH: The lessons also include a concern for the marine environment, where kids even perform experiments.

[VOICES OF KIDS DOING WATER QUALITY TESTING]

NINH: The kids dip a strip of pH paper in the water, just one of the hands-on activities offered through a collaboration between Courageous and a local environmental organization Save the Harbor/Save the Bay. It’s called the Green Boat, and in this floating classroom kids get to do things like tow for plankton, measure water transparency and even cleanup the harbor. Here’s Gabriela, again.

GABRIELA: Sometimes I see people throwing trash in the harbor, and I sometimes ask them to stop. I never really realized how much trash we use and how bad the environment is if we throw trash in the harbor all day.

NINH: Youth Director Kate Henderson says kids often become environmental stewards after they enter the program.

HENDERSON: You get it all the time. What we’re teaching these kids is not only to enjoy the outdoors and Boston Harbor but also to become advocates for the harbor so we have so many kids who have gone into the fields of marine biology and environmental science, which is really great to see that these kids really want to give back.

Kids from Camp Harbor View race their sailboats. (Photo: Amie Ninh)

NINH: Aboard the Green Boat are youth helpers from Save the Harbor/Save the Bay like 16-year-old Mark Rose from Dorchester.

ROSE: To be honest, I really didn’t know most of these places existed until now, like all the islands, the Boston Harbor Islands, the Courageous Sailing Centers. All of this is so new to me.

NINH: Mark now says his goal is to get friends and family from his community to explore the harbor as well.

MARK: The kids here are the ones who actually taught me how to sail. I’ve never been on a sailboat my whole entire life before I started working. People around my community, they don’t really get out. I want to make it possible for them to come out here anytime they want. I definitely want to come back next year. You have the time of your life.

NINH: And for Mark and the other kids, the limited view of the world around them now stretches far beyond their horizons. For Planet Harmony and Living on Earth, I’m Amie Ninh.

[BOAT NOISES]

YOUNG: Amie reports for our sister program, Planet Harmony, which welcomes all and pays special attention to stories affecting communities of color. Log on and join the discussion at My Planet Harmony dot com.

Related links:

- Courageous Sailing

- Camp Harbor View

- Save the Harbor/Save the Bay

The Wave

Read about huge waves in Susan Casey’s book published by Knopf Doubleday.

YOUNG: Now with luck, none of the kids sailing in Boston Harbor will ever encounter a truly massive wave. Monster waves that gobble up ships leaving no trace nor survivors are the stuff of myth and legend – and Hollywood, think “Poseidon Adventure”. But better instruments and satellite tracking have shown that huge freak waves are not really that uncommon. Susan Casey, who wrote about great white sharks in her book “The Devil’s Teeth”, has a new book about great blue waves. It’s called “The Wave: in Pursuit of the Rogues, Freaks and Giants of the Ocean”. She told Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood that even today, an ocean going ship is engulfed by a mammoth wave every two weeks.

CASEY: Those ships are hitting rogue waves in storm conditions, you know, waves that can be three and even four times bigger than the seas around them, so if you’ve got 50 foot seas, you can easily get a 100 or a 125 foot rogue wave. And, scientists really had to reckon with the fact that these waves do exist.

CURWOOD: In your book, Susan Casey, you tell the story of a scientific ship in the UK that documented these giant waves. Could you tell us that story now please?

CASEY: Yes, the RRS Discovery. I read about this and I had to read the article twice to believe what I was reading- was a group of scientists from Britian and Scotland who were out in the North Atlantic and they were hit by about 48 hours worth of 60,70,80,90 and even 100 foot waves. And, they were trapped out there in these waves, and almost didn’t survive them.

And, what was great, not so much for them, but for everyone else, was that the ship had all kinds of state-of-the-art scientific instruments on it, so it was perfectly equipped to capture every measurement of what the ocean was doing. And, what they found out and eventually published a paper about was that the models, the meteorological models and the wave models, had not predicted these waves, that they shouldn’t have been there, and that in fact, the kinds of really extreme and really freakish seas that had been sort of seen as sailors’ tall tales, really did exist. There was direct proof there.

CURWOOD: So what’s a really big wave?

CASEY: Well, in the book, I talk about a wave that happened in 1958 in a very spooky area of the Alaskan coast that was 1,740 feet tall. That’s a big wave! (laughs)

CURWOOD: Wait a second, that’s the empire state building!

CASEY: I think plus some. That is the biggest wave that has been measured accurately. And the reason they were able to know exactly how big that wave was, was geologists were later able to go in and measure where the trees stop. It’s like a razor came along and just shaved them all off. And when they were up there, looking into that, they found out that this had happened quite regularly in this bay.

CURWOOD: Now this is all related to landslides and earthquakes, that sort of thing?

CASEY: Yes, and in the book, I talk about several different types of giant waves. In that case it was kind of a localized tsunami. The most dramatic waves that we have here on Earth are caused by big landslides either on the land that then fall into the water, or below the sea and cause tsunamis. And, they can be provoked by earthquakes, they can be provoked by a volcanic island collapsing, but those are the really dramatic ones. Those are the ones that re-write the maps.

CURWOOD: Now, one thing that you mention in your book is that the average height of ocean waves seems to be increasing. Why is that? And, should we be worried about it?

CASEY: Well, I think that ocean has always been a very powerful and volatile place. And, that the increase that seems to be happening in waves has to do with a number of different effects. One of them is, are these over-arching climate patterns, and these are really very poorly understood things because we haven’t had the ability to measure, you know, long-time climate patterns because we haven’t been doing it for very long, and we haven’t even been around for very long when you think of geological time. So, that, the increased wind that comes from a warmer ocean and potentially stormier environment, just caused by climate change…So, I don’t know about worried, but aware, certainly.

CURWOOD: So, lets talk about climate change and big waves. You list several things in your book that could change wave patterns. For one thing you say that climate change could increase the frequency of earthquakes. How’s that?

CASEY: This is what happens: when glaciers melt, they tend to change distribution of weight. It’s either more or less weight on the land or on the seabed, and it’s a pretty dramatic amount, like if the sea goes up even a small bit in terms of sea level, that adds up to so much weight and that then weighs the tectonic plates and various fault lines differently. They call it isostatic rebound.

And, what they suspect is that at the end of the last ice age, when the glaciers were sort of pouring into the ocean and parallels with what we’ve got now with rapidly shrinking glaciers, there was a flurry of earthquake and volcanic activity. You know, when things are moving around, when there’s sediment or earthquakes moving around below the water, or even on land and falling into the water, that can equate to a tsunami.

CURWOOD: So, how likely is it that science is going to be able to predict big waves, or should we just, you know, chalk ‘em up to the unpredictable nature of nature?

CASEY: Well, I think nature is always going to defy our attempts to completely dissect it in any sort of rational, logical way, because chaos and random events are really a part of its complexity. But there are some very, very smart people trying to make better climate models and better wave models. And, to better understand how we can be in harmony with these potentially destructive or, certainly incredibly powerful forces, and that work just goes on continuously.

And, when you have something like the tsunami of 2004 and a tragedy like that or, the sort of amazing power that was witnessed as the storm surge came over the levees in Hurricane Katrina, I think it shows how important this is going to be for us to understand this in such a way that we can live with it.

CURWOOD: Part of your book you devote to a search for, I guess a surfing holy grail, what, to ride a hundred foot wave?

CASEY: Yes.

CURWOOD: Why would someone want to ride a hundred foot wave? It sounds like a death wish to me!

CASEY: I would definitely agree with you. I wanted to find out. I saw a 20-foot wave years ago and had never forgotten how terrified I was when I saw it. And somebody was riding it and I didn’t understand how he could survive it. And then, a few years later, they started tow surfing and I saw pictures of some of the characters in my book riding 60 and 70-foot waves, and I was absolutely riveted. I couldn’t understand how people didn’t die every time they went out.

CURWOOD: You need to explain tow surfing.

CASEY: Tow surfing was invented in 1995 as a means to ride bigger and bigger waves. Waves that are bigger than, say, 30 or 40 feet, are not possible for us to paddle into. They’re just moving too fast. I described it in the book as trying to catch the subway by crawling. You’re just not going to get it, it’s just going to go thundering past you. So, the biggest most interesting waves for some of the surfers were in the, what they call the, un-ridden realm.

And they, eventually, through a sort of painful trial and error, figured out that they could use jet skis to pull a partner onto the crest of the wave. And, it could be theoretically, it could be any size wave, it could be a 100-foot wave, but they were doing it with 60 and 70-foot waves with success.

CURWOOD: This sounds absolutely nuts! A jet ski is not the easiest thing in the world to handle, now you’re going to have this 60-feet above… You know, there’s a big hole at the end of that wave!

CASEY: Well and not to mention that water is, you know, 800-times denser than air, so when it comes crashing down on your head it does some damage. And, as I said, it was a very painful trial and error process.

Read about huge waves in Susan Casey’s book published by Knopf Doubleday.

CURWOOD: How many people get killed doing this?

CASEY: Well, every so often someone will get killed or injured very badly. I think what happens a lot more often is they get scared to the point where they never want to do it again. I asked a lot of them to describe to me what it feels like to be held down by a wave that big, and I think it’s a truly fearsome experience. Some of them, the best surfers that I encountered and interviewed, said, you know, they had instances where they really, as one surfer put it, saw the Mandalla. And they didn’t want to go back out, right back out there and do this think they loved. It took years to feel like they were in control again.

CURWOOD: In other words, they thought they were about to die. They were drowning.

CASEY: Yeah, and most of them do have that experience.

CURWOOD: And you feel fine going out to sea knowing that these waves are out there?

CASEY: I definitely would, it’s just, I think that you always have to have your wits about you and you have to know that these waves are out there. And, I also think the last thing that I would want people to do is read this book and think ‘I’m more scared of the ocean.’ I mean, I feel as though part of my purpose in writing it was so we could understand more this great force that’s so much a part of the planet that we live on, and if we understand it more then maybe we can respect it a little bit more. Because, one of the things that seems so counterproductive is to treat the ocean like it’s this other thing over there and we can dump stuff into it and we don’t have to worry. But what I’d like to do is shed more light on what’s going on in the darkest heart of the ocean.

CURWOOD: Susan Casey’s new book is called “The Wave: In Pursuit of the Rogues, Freaks and Giants of the Ocean.” Thank you so much, Susan.

CASEY: Thank you!

Related link:

Watch a Youtube interview with Susan Casey & surfer Laird Hamilton.

BirdNote ® - Shorebirds on the Wing

Black-bellied Plovers. (Photo: Tom Grey ©)

[BIRD NOTE THEME]

YOUNG: And now, we take a birds’ eye view of shorebird migration, in this installment of our new occasional series, BirdNote ®.

[THE CALLS OF HUDSONIAN GODWITS AND BLACK-BELLIED PLOVERS]

CORRADO: In September, all across North America, the southward migration of shorebirds reaches its peak. Millions of shorebirds, the sandpipers and plovers that grace our shorelines, are on the move. And many birders now flock to the mudflats to watch the annual pilgrimage. Most shorebirds nest in high northern latitudes such as the Arctic tundra. Where are these migrants bound? Well, a surprising number fly all the way to South America. Hudsonian Godwits…

[THE CALLS OF HUDSONIAN GODWITS]

Black-bellied Plovers on the wing. (Photo: Tom Grey ©)

CORRADO: …which hatch their young near Hudson Bay and in extreme northwest Canada, winter in southeastern South America – some as far south as Tierra del Fuego.

[CALLS OF HUDSONIAN GODWITS]

CORRADO: Lovely American Golden-Plovers fly similar distances…

[CALLS OF AMERICAN GOLDEN PLOVERS]

CORRADO: Some log nearly 20,000 miles in their annual circuit from the Argentine Pampas to the Arctic and back.

[THE CALLS OF AMERICAN-GOLDEN PLOVERS]

CORRADO: The beautiful Black-bellied Plover…

[CALLS OF BLACK-BELLIED PLOVER]

CORRADO: Which also nests in the far north, has a very different migratory strategy.

[CALLS OF BLACK-BELLIED PLOVER]

Black-bellied Plover. (Photo: Tom Grey ©)

CORRADO: Wintering primarily on coastal beaches and mudflats, Black-bellied Plovers spread themselves out for the colder months all the way from the Canadian border to central South America.

[BLACK BELLIED PLOVER CALLS]

YOUNG: That’s Frank Corrado for BirdNote ®. For photos and more information, go to our website L-O-E dot org.

Related links:

- BirdNote ® “Shorebirds Migrate South” was written by Bob Sundstrom.

- Bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Hudsonian Godwit calls recorded by G.A. Keller and W.W.H. Gunn. Black-bellied Plover calls recorded by R.C. Stein. American Golden-Plover recorded by G. Vyn.

YOUNG: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, and Mitra Taj, with help from Sarah Calkins, and Sammy Sousa. Our interns are Nora Doyle-Burr and Honah Liles. We had engineering help this week form Dana Chisholm. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Steve Curwood is our executive producer. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org. And check out our Facebook page, it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth hormones on their cows. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners. The Ford Foundation, The Town Creek Foundation, The Oak Foundation—supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues. And Pax World Mutual Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at Pax world dot com. Pax World for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI – Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth