March 4, 2011

Air Date: March 4, 2011

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Can REDD Work for the Amazon?

View the page for this story

Extreme drought has turned the Amazon rainforest into a source of carbon dioxide for two of the last five years. Brian Murray, director of Economic Analysis at the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, talks to host Bruce Gellerman about what drought in the Amazon might mean for the future of REDD, the United Nations mechanism designed to Reduce Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation. (06:20)

Curing Mosquitoes of Malaria

View the page for this story

Organizations around the world have been trying to battle malaria with insecticides. But evolution has taken its course, and now many mosquitoes are building a resistance to these efforts. Host Bruce Gellerman talks with Raymond St. Leger, an entomologist at the University of Maryland, about his new research that uses a transgenic fungus to attack the malaria parasite inside of the mosquito, before it has a chance to bite a human. (06:20)

The Future of Biofuels and the Weather

/ Lisa RaffenspergerView the page for this story

The call for energy independence – and a federal mandate to increase use of renewable fuels - has farmers and scientists looking to new biofuel crops like switchgrass. But these new crops need water and they also may affect the water cycle. IEEE Spectrum’s Lisa Raffensperger reports on a team at Iowa State University that is studying computer models to see how biofuels may change the agricultural landscape and the weather. (05:35)

Science Note/Sting to the Heart

/ Jessica Ilyse KurnView the page for this story

New research suggests that venom from the Central American bark scorpion can be used in heart bypass surgery to prevent graft failure. Jessica Ilyse Smith reports. (01:30)

The Rx for Healthy Kids

View the page for this story

The National Environmental Education Foundation’s Children and Nature Initiative has the prescription for healthier kids—a breath of fresh air. Doctors from New Jersey to California are encouraging kids to get back out into nature by connecting them with programs at local nature reserves, where they can reconnect with their inner wild child—literally. Host Bruce Gellerman talks to one of NEEF’s “Nature Champions,†Dr. Charles Owyang. (05:20)

Sea Otters at Bay

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Sea otters may be adorable creatures, but not everyone loves them. Fishermen often blame the sea otter for continuing declines in shellfish. Salt Marsh Diary author Mark Seth Lender watched otters at the Elkhorn Slough in Monterey, California. He writes that they are both playful and have a unique and vital niche in nature. (03:35)

The Language of Landscape

/ Donna SeamanView the page for this story

Living on Earth continues its series exploring features of the American landscape, based on the book Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape, edited by Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney. In this installment, writer Donna Seaman explains the term "slough." (01:50)

Generation Hot

View the page for this story

Scientists predict that the next fifty years will bring pretty serious climate change. While it’s difficult to imagine our world that far in the future, author Mark Hertsgaard, in his new book, Hot, perceives those threats as dangers to the well-being of his young daughter. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood speaks with him about focusing the power of parents towards climate-action. (08:40)

Botanical Books

/ Laurie SandersView the page for this story

The technological revolution has led to a big change in how books are published – and read. But this isn’t the first time the nature of books has changed. In fact, looking back some five hundred years ago, books about plants and herbs underwent a revolution. Producer Laurie Sanders visited Smith College’s Rare Book Room to dig into botanical literature. (06:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bruce Gellerman,

GUESTS: Brian Murray, Raymond St. Leger, Charles Owyang, Mark Hertsgaard

REPORTERS: Lisa Raffensperger, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Mark Seth Lender, Donna Seaman, Laurie Sanders

[THEME]

GELLERMAN: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth. I’m Bruce Gellerman.

[AMAZON RAINFOREST SOUNDS]

GELLERMAN: A financial scheme to save the Amazon from chainsaws is expensive but it’s a walk in the park compared to saving it from drought – that may be impossible. And scientists discover a novel way to kill a deadly parasite.

ST. LEGER: Now the scorpine toxin is from the imperial scorpion. A great big scorpion, a huge scorpion, in fact, which has got a rather placid personality, plays well with children.

GELLERMAN: And could save millions of kids from malaria. Also leafing through old botany books and toasting their wisdom.

SANDERS: He said, “The many virtues of hops do manifestly argue the wholesomeness of beer above ale. For the hops rather make it a physical drink to keep the body in health rather than an ordinary drink for the quenching of our thirst.â€

GELLERMAN: Old books - and beer. These stories and more – just ahead on Living on Earth, stick around!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, and Stonyfield Farm.

[THEME]

Can REDD Work for the Amazon?

Historically, deforestation in the Amazon was attributed to slash and burn agriculture for raising soy or cattle. Increasingly, the forest is being degraded by drought, which stresses and kills trees. (Photo: Lou Gold)

GELLERMAN: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I'm Bruce Gellerman.

[RAINFOREST NOISES, AKAKI BIRDS CALLING]

GELLERMAN: The Amazon is by far the world’s largest rainforest. In this remote corner of the forest, high overhead in the canopy, Akaki birds warn of intruders as our footsteps crunch dead leaves on the forest floor.

The vast Amazon is more than a rainforest--it's also a giant carbon storage system. Scientists call it a carbon sink. Rainforests, like the Amazon, absorb billions of tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and sink, or store, the climate changing gas in the standing trees. And that’s where the UN plan known as REDD comes in. Advocates say REDD is the fastest, cheapest way to save the forest from chainsaws and stall global warming.

The REDD scheme is simple. Make the carbon stored in the trees worth money, so farmers and timber companies have an economic incentive not to cut them down. Brian Murray, Director of Economic Analysis at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, thinks REDD can work.

MURRAY: The idea here is to change the economics because in many parts of the world, it’s more economic to knock the tree down than it is to leave it standing. Deforestation and degradation are one of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the world. This occurs primarily in the tropical countries.

Brian Murray is Director of Economic Analysis at the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University. (Duke University)

So, different policies, from international policies to national policies throughout the world, have tried to develop financing mechanisms for REDD that pay these countries to reduce their emissions below some baseline level. And the idea here is when they reduce these emissions below some baseline level, they’re helping solve the climate change problem and they’re receiving compensation for it.

GELLERMAN: Potentially, rainforest REDD could be worth a lot of green: a hundred billion dollars a year or more. Nations with rainforests would put a value on the carbon in their trees, and then countries or companies that want to offset their fossil fuel emissions could buy REDD credits.

The scheme could work as long as there's a forest to save. But we're losing the Amazon rainforest. Two devastating droughts in the past five years have turned it from a giant carbon sink to a huge source of climate changing gas. So what happens now to the REDD financial scheme as the forest dries and dies? Again, here’s Duke University professor Brian Murray:

MURRAY: Well, that is the question. Just like many investments in the world, you can think of it as a big investment, and sometimes those investments, pardon the pun, go up in flames. And the issue is, what have you done to protect yourself against that?

Under the REDD scheme to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from deforestation and degradation, polluting countries will pay rainforest nations to stop cutting down their trees. (Photo: Leo F. Freitas)

When these countries get paid for these emission reductions, they’re often translated into credits that others can use to offset their emissions. And if those credits are sold into the market, and somebody has used it and said, ‘I’ve offset my emissions because I’ve saved these forests in the Amazon,’ then, you know, then a deal has been done. The problem is then if you come in later and those forests end up back in the atmosphere again because of fire, that original deal doesn’t look like such a good deal. So how are you going to cover that?

Well, one way to do it would be to have something like insurance mechanisms set aside to say, ‘Oh okay, well we issued a hundred million tons to this Amazonian country for reducing its emissions, but it turns out that 50 million tons ended up back in the atmosphere.’ Then you need to have some provision to, essentially, cancel out those 50 tons from the crediting mechanism.

GELLERMAN: But let’s take a real-world example. In 2005, you had this drought in the Amazon, then in 2010 you have a worse drought. These are the droughts that aren’t supposed to happen but once in a hundred years! Combined, they emitted more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than the United States and China produce combined. If I was a country, or somebody paying to keep the carbon locked in that forest, I’d be out!

MURRAY: In a way, it’s like many other insurable events. We have hundred year floods that occur twice in a decade as well, and it creates problems. And so, what the insurance industry does is they try to spread the risks across a lot of different areas and a lot of different types of risks, so that they can handle these big risks. If these risks turn out to be too frequent and too large, then yes, the mechanism may not be able to handle them, and another type of approach is going to be necessary to help save these forests.

GELLERMAN: Let’s say you have insurance against the economic loss, but you still lose the overall carbon in the trees, which was, after all, the goal. I mean no amount of insurance is going to make up that carbon.

MURRAY: Well, one way of looking at it is: So if this is all part of credits that are trading in the market, and if your main concern is that by crediting a reduction in deforestation emissions in the Amazon, you’ve allowed somebody else in the world to increase their emissions, say from a power plant.

I mean that’s how these carbon markets work. Then what you want do is, what you’re trying to recover is to say, ‘Okay no, you can’t emit from that power plant, or if you emitted from that power plant, and used these credits from deforestation to allow you to emit from that power plant, you have to go out and get other allowances to replace those, so that you’re still in compliance.’ Now I should add to that, without this market, without this mechanism for REDD, this is still a problem - right?

Historically, deforestation in the Amazon was attributed to slash and burn agriculture for raising soy or cattle. Increasingly, the forest is being degraded by drought, which stresses and kills trees. (Photo: Lou Gold)

Because this carbon does end up in the atmosphere regardless of whether it was paid for or not. So we have an economic situation we’re trying to address through making sure that we replace those credits in the market, but we have a real potential environmental disaster at work here, which is to say, that these forests that used to be absorbing carbon dioxide are now introducing them to the atmosphere.

GELLERMAN: Under a REDD scheme, would Brazil be obligated to replace the trees that died in the drought?

MURRAY: That is an open question. The international mechanism that’s being proposed says that there must be safeguards against reversals. When you pay someone to reduce their emissions, but then those emissions go back up a few years later as a result of these influences, that’s considered a reversal. The mechanism has to find a way to deal with these reversals, or else those who have developed it, in the international community, realize that this problem could undermine the entire integrity of the system.

GELLERMAN: Brian Murray is Director of Economic Analysis at the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University. Professor Murray, thanks a lot.

MURRAY: Thanks for having me, Bruce.

GELLERMAN: To hear more Living On Earth stories about REDD, visit our website, L-O-E dot O-R-G.

Related links:

- UN REDD

- Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions

- Click here to hear previous LOE REDD coverage

[MUSIC: George Clinton “Lickety Split†from plush Funk (Montreux Sounds 2005).]

Curing Mosquitoes of Malaria

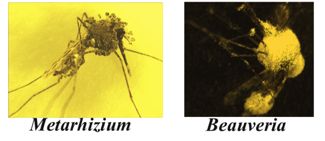

A mosquito infected by the insect pathogenic fungus. (Raymond St. Leger)

GELLERMAN: Malaria is an insidious disease. It destroys lives and undermines the development of poor nations. Mosquitoes carrying a parasite that causes malaria infect nearly a half a billion people a year, mostly in the tropics. Annually more than a million people die from malaria. Most are children.

Mosquito nets and pesticides help, but at best, the battle against malaria is at a standoff. Now scientists have developed a new way of destroying the parasite that causes the disease, and joining me is the researcher who led the effort. Professor Raymond St. Leger is an entomologist at the University of Maryland. Professor, welcome to Living on Earth.

ST. LEGER: Thank you very much.

GELLERMAN: As I understand it, you’re using a genetically modified fungus to kill the malaria parasite. Which fungus, and how does it work?

Dr. Raymond J St. Leger used scorpin, a toxin found in the Imperial Scorpion’s venom, to cure mosquitoes of malaria. (Raymond St. Leger)

ST. LEGER: Yes, we are. It’s a fungus called Metarhizium anisopliae, and it infects insects through their skin. And, what we’ve done is we’ve taken a gene encoding a human antibody, and we also tried a gene encoding an anti-malarial toxin, and we put those genes inside the fungus. And so now we’ve got a fungus that acts like a contact insecticide.

It lands on the insect’s skin, penetrates into the blood of the insect, and then will produce human antibody against the malaria, and basically cure the mosquito of malaria within a couple of days of infection.

GELLRMAN: But you didn’t want to kill the mosquito, you want to kill the parasite that carries the malaria. Why wouldn’t you want to kill the mosquito?

ST. LEGER: Well, we can kill the mosquito. We can engineer the fungus to express insecticidal toxins from a spider, and they’ll kill a mosquito in a couple of days. But the problem we might have then is, the likelihood is that the insects will evolve resistance to the fungus as well. So we wanted to change the strategy: target the malaria inside the mosquito.

Mosquitoes infected by two different insect pathogenic fungi. (Raymond St. Leger)

GELLERMAN: Now you’re genetically modifying the fungus with a scorpion toxin. How’d you come up with that?

ST. LEGER: Ah, well, that’s scorpine as it’s called - it’s a toxin which has been studied for a few years now by different groups. And, it’s quite interesting - it’s an antimicrobial toxin, and it was shown to be effective against plasmodium a couple of years back. Now the scorpine toxin is from the Imperial Scorpion, a great big scorpion, a huge scorpion in fact, which has got a rather placid personality, plays well with children.

GELLERMAN: And I guess saves their lives.

ST. LEGER: Yes, this scorpine toxin could actually save lives, just by putting it in the right place. And the fungus is our tool and utensil for doing that. It’s the delivery system.

GELLERMAN: So how do you get the fungus into the mosquito?

ST. LEGER: The fungus can be applied like any chemical could be: You could spray it or you could put it on a cloth in the house, you could put it on bed nets, you could even paint it on walls. And if the mosquito contacts the fungus, the fungal spores, they germinate and they know to penetrate into the skin, they’re programmed to do that.

GELLERMAN: How effective, Professor, are these genetically modified fungi?

ST. LEGER: With mosquitoes, which have very

advanced malarial infections indeed you know - 11 days after they’ve taken an infected blood meal, when they’re full of malaria – we can infect them at that stage with this fungi, and within a couple of days, we will have reduced the amount of malaria parasites by something like 98 percent.

What that means is that 75 percent of the mosquitoes will have no malaria parasites at all, and the remaining 25 percent of the mosquitoes will have very few. And that’s just a couple of days after infecting with the fungus.

GELLERMAN: How about the cost? The expense - is it very expensive to do this?

ST. LEGER: No, it shouldn’t be, because they already use a related fungus for locust control. It’s mass produced in Africa, it’s mass produced in China and Australia, and basically it’s about as expensive as chemical insecticide.

GELLERMAN: And safe? I mean, you’ve got this genetically modified fungus… is it safe in the environment?

ST. LEGER: Well the wild-type fungus, the original fungus, is very safe. It’s been used for a long time, and it’s hard to see any tangible risk from what we’re doing. Because we’ve taken a gene, which is specific - the antibody gene - is specific for human malaria. It doesn’t even recognize mouse malaria, or chicken malaria, so it’s totally specific for human malaria.

And it doesn’t affect the insect in any way; it doesn’t affect anything else but human malaria. And it’s got an on-off switch, the promoter, which means that this gene would only be made in insect blood - it wouldn’t be made anywhere else the fungus happened to be.

GELLERMAN: So, can you use this genetic technology to kill other insect-borne diseases?

ST. LEGER: The fungus we’re using is quite specific to mosquitoes and their relations. But there are other fungi which will attack ticks, for example – say the ticks which carry lyme disease. And we have already a fungus which attacks tsetse fly, which carries trypanosomes - the sleeping sickness.

And there are antibodies already to the lyme disease and to sleeping sickness, trypanosomes, so we’re currently engineering these different specific strains to produce those antibodies in other toxins to see if it will work. If it works against malaria, then it should also work against these other pathogens.

Scorpine, which is anti-malarial, is also known to be effective against the dengue virus, and that virus kills 350 thousand people a year.

GELLERMAN: So does this mean we can finally defeat malaria?

ST. LEGER: No, we don’t think there is any particular silver bullet that is going to take out malaria. You’re going to have to use a range of different procedures. The fungus could be used along with chemical insecticides, for example, and the fungus could help prevent resistance developing to the insecticide.

New treatments for malaria, like vaccinations and so on, because malaria is present in so many different countries in so many different habitats and situations, there’s going to be no one single cure-all. But we think that our transgenic fungi could make a real, significant, substantial impact, should improve people’s lives, should save lives in sub-tropical Africa, where we hope to do the first field trials.

A mosquito infected by the insect pathogenic fungus. (Raymond St. Leger)

GELLERMAN: When will you do those field studies?

ST. LEGER: We should hope to do the initial studies under very, sort of, contained conditions within the next couple of years. There’s no real precedent for this sort of work, so we’re being cautious, and we’re making sure that everyone involved – all the people we call stakeholders, the people in the neighborhood and so on – are going to be onboard and know exactly what we intend to do.

GELLERMAN: Raymond St. Leger is a professor of entomology at the University of Maryland. His study ‘Development of Transgenic Fungi that Killed Human Malaria Parasites in Mosquitoes’ is in the latest edition of Science Magazine. For a link, go over to our website, loe.org. Professor, thanks a lot, I really appreciate it.

ST. LEGER: Thank you, it was very nice speaking with you.

Related link:

Read an article about this new study

[MUSIC: Meshell Ndegeocello “Die Young†from Devil’s Halo (Mercer Street Records 2009).]

GELLERMAN: Just ahead - a prescription for obese kids: a heavy dose of nature. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

[CUT-AWAY MUSIC: Pat Metheny “Every Summer Night†from Letter From Home (Geffen Records 1989).]

The Future of Biofuels and the Weather

Farmer John Sellers grows switchgrass in southern Iowa. (Photo: Lisa Raffensperger)

GELLERMAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bruce Gellerman. As oil prices soar, the call for energy independence is growing loud. And the nation’s farmers are getting the message: They’re eager to grow biofuels to fill gas tanks and meet the goal. The debate over biofuels is typically about using farmland for food or fuel.

But there are questions about a more fundamental farm issue: water.

All those bioenergy crops could affect what's called the water cycle and possibly the weather. In Ames, Iowa, engineers are modeling the future of biofuels to get some answers. Lisa Raffensperger of the IEEE Spectrum, National Science Foundation program "The Water-Energy Crunch: A Powerful Puzzle," has our report.

[MOUSE CLICKS, COMPUTER SOUNDS]

RAFFENSPERGER: In a tiny windowless office on the Iowa State University campus, engineer Brian Gelder pulls up a map of the U.S. on his computer screen. It’s a vision of the future.

GELDER: In the high plains, especially in parts of Oklahoma and Kansas, we’re projecting fractions of the county that may reach up to about 45% of the county will be switchgrass in 2022.

RAFFENSPERGER: Nationwide, that adds up to an area about the size of Missouri newly planted in switchgrass. Behind the change is a law that requires 36 billion gallons of renewable fuel to be blended into our gasoline by the year 2022. Switchgrass is one of the most promising of the biofuel crops.

ANEX: So if we're going to make biofuels, it's not a little marginal change in the landscape. We're going to make a big change.

Rob Anex, an associate professor at Iowa State University, is part of a team looking at how biofuel crops may change the weather. (Photo: Lisa Raffensperger)

RAFFENSPERGER: That’s Rob Anex, also at Iowa State. His team is creating computer models to predict what this big change may mean for the weather. How do plants affect the weather? Well, when plants breathe out oxygen, it’s saturated with water. That’s called transpiration. Switchgrass will grow larger than corn on the same amount of land, but it’ll also suck more water from the soil and transpire more water. That water will go into the atmosphere, and come down as rain somewhere else.

[WIND AND BLOWING GRASS]

RAFFENSPERGER: It’s sunset in rural southern Iowa, and a spring storm is moving in. The switchgrass, dry beige stems about waist high, bends over nearly flat in the wind. This is what large swaths of Oklahoma and Kansas will soon look like if the models are correct.

[FOOTSTEPS ON THE GRASS]

RAFFENSPERGER: This field belongs to farmer John Sellers. He’s a sort of switchgrass guru.

SELLERS: That’s the beauty of these native grasses. They hide all of the nutrients in this plant in the root all winter long.

Farmer John Sellers grows switchgrass in southern Iowa. (Photo: Lisa Raffensperger)

RAFFENSPERGER: Switchgrass has many beauties, actually. It’s native, not a food crop, and can grow on marginal land. It’s also highly productive. Near where Sellers lives, an average acre of land produces 4.7 tons of corn, but could produce 5 and a half tons of switchgrass, which could someday mean a lot more ethanol produced.

But it’ll also mean a lot more water. Back at Iowa State University, Rob Anex explains the correlation.

ANEX: There's a nice linear relationship there, that if you want more biomass, you're going to transpire more water.

RAFFENSPERGER: For instance, that bonus growth of switchgrass in southern Iowa - each acre will transpire about 30,000 additional gallons of water into the atmosphere. To see how changing crops could affect the water cycle, the Iowa State team ran a test of their weather model. Chris Anderson is a climate scientist working on the project.

ANDERSON: We extracted one day in 1980 from it, and that day was February 26th in 1980.

Climate scientist Chris Anderson of Iowa State uses computer models to see how crops like switchgrass affect the water cycle. (Photo: Lisa Raffensperger)

RAFFENSPERGER: And on that day, they asked a simple question: what if almost all of Kansas, Oklahoma, and the Texas panhandle had been growing switchgrass? How would the summer of 1980 have turned out? Anderson points to a blotch of blue covering western Kansas and Oklahoma.

ANDERSON: And you can see it's drawing from this soil moisture level and reducing the amount of soil moisture down there. In this case, it reduced it by about 5 percent.

RAFFENSPERGER: And on a different map, rainfall. There’s a band of yellow and red from Iowa to Michigan.

ANDERSON: So the crop is putting more moisture in the air. It's going downwind and it's creating more storms.

RAFFENSPERGER: The team is currently running models of an alternate past - how weather would have looked over 25 years if switchgrass had covered as much land as it’s projected to in 2022. They expect to see more rainfall downwind of the switchgrass. They also expect more intense rains, the kind that cause erosion and flash flooding. So, should we be worried? When you ask Rob Anex, he pauses.

ANEX: It all depends on how we decide to make biofuels. And the reason that I'm hedging and saying it that way is that there's lots of different ways to grow biomass.

RAFFENSPERGER: Using agricultural waste like corn leaves and stalks won’t require more cropland or water. And some places have enough water for new crops. Anex hopes policymakers carefully consider the larger picture of biofuels and the water cycle, because it’s a complicated one.

ANEX: What we do on the landscape, how we use our land, affects the weather, but it affects the weather in other places.

RAFFENSPERGER: As homesteaders in the American West once said, ‘Rain follows the plow.’ Though now we’re learning it may follow from a longer distance than they ever realized. For Living on Earth, I’m Lisa Raffensperger.

GELLERMAN: Lisa’s story is part of the IEEE Spectrum, National Science Foundation program "The Water-Energy Crunch: A Powerful Puzzle."

Related links:

- IEEE Spectrum's Engineers of the New Millennium: The Water-Energy Crunch: A Power Puzzle

- Rob Anex, Assoc. Professor, Iowa State University

- Chris Anderson, Scientist, Climate Science Program, Iowa State University

- EPA's 2011 Renewable Fuel Standards

[MUSIC: Jefferson Airplane “Things Are Better In The East (Marty’s Acoustic Demo)†from After Bathing At Baxter’s (BMG Heritage 2003).]

Science Note/Sting to the Heart

A Bark Scorpion. (Photo: Wikipedia Creative Commons)

GELLERMAN: Coming up – getting in shape doing what comes naturally. But first, this week’s Note on Emerging Science from Jessica Ilyse Smith.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

SMITH: Scorpion stings can be life-threatening. But new research suggests that venom from the Central American Bark Scorpion may save lives by reducing heart bypass failure.

During bypass surgery, a vein is grafted into the heart. Sometimes, the body’s healing response kicks in and creates new cell growth in the vein. This growth can restrict blood flow and is the most common cause of graft failure. To prevent this, researchers have turned to an ingredient in the Bark Scorpion’s venom: margatoxin.

A Bark Scorpion. (Photo: Wikipedia Creative Commons)

Scientists believe margatoxin is 100 times better than any other known compound at preventing bypass grafts from failing. Just a few molecules of the toxin obstruct the movement of calcium ions, which carry messages between cells. Stopping these messages can prevent unwanted cells from growing.

The new medication containing margatoxin is unlikely to take the form of a pill or a shot, but may be sprayed onto the vein before surgery. Scientists aren’t yet sure of the treatment’s long-term success. But we do know there’s more to this Bark Scorpion’s sting than we once thought. That’s this week’s note on emerging science, I’m Jessica Ilyse Smith.

The Rx for Healthy Kids

Dr. Charles Owyang.

GELLERMAN: What do you do with kids who think the great outdoors ain’t so great? Seems there are a lot of them and all that couch time is taking its toll: A third of the population under 20 is overweight or obese. That puts these kids at risk for diabetes, heart disease, and asthma. In fact, this could be the first generation of children with a lower life expectancy than their parents.

Dr. Charles Owyang says what kids need is a healthy dose of nature, and he has just the prescription. Dr. Owyang is a pediatrician in the San Francisco Bay Area, and he's training other physicians in writing prescriptions for nature as part of the National Environmental Education Foundation’s Children & Nature Initiative. Dr. Owyang, welcome to Living on Earth.

OWYANG: Thank you!

GELLERMAN: You guys aren't kidding around – you really are talking about writing prescriptions to get outside for kids!

OWYANG: Yes, we sure are. It’s a phenomenal way to really get kids back out to nature, and it seems like, you know, it’s something that we can really get traction on and kids and families are responding.

GELLERMAN: But is this really necessary? You know, I mean it’s kind of a sad statement – when I was a kid, you wouldn’t have to tell a kid to go out and play.

OWYANG: Yeah, these days, you know, there’s just more barriers sometimes to getting kids outside. Part of it is, perhaps, some of the social media and the internet, and other things also include that some communities are getting more and more built up, and sometimes it’s hard to just go down the block to the neighborhood park, or where there’s trees, and go out and play.

And, it’s something that parents actually have to think about a little bit more, especially with their busy schedules. And writing that prescription for nature gives them something to take out of the office that reminds them to get back out and to play. And, you know, most people, when they actually experience it, they just are amazed at how wonderful it is to actually take a walk out by the Bay, or out in a nature reserve and see egrets and pelicans and birds, and smell the fresh air. It’s just a world apart.

Dr. Charles Owyang.

GELLERMAN: But for a kid who’s playing Kill Zone 3, you know, the video game, do they ever look up at you and say, ‘Yeah, right doc.’

OWYANG: (Laughs). You know, sometimes they do. But we’ve been very fortunate that this program is so excellent that it has a lot of visual handouts that actually entice the child a little bit more. And I show them the different programs: Every weekend there are just multiple programs that they can go to, like photographing nature, learning how to identify birds on the bay, doing GPS scavenger hunts for different treasures at the nature reserve…so, they’re actually a lot of fun.

And I show them some of the rewards that they can earn, like binoculars, a children’s plushy woodpecker toy, a tote bag…the kids actually think, ‘Wow, this might be kinda cool.’

GELLERMAN: But it’s a little bit like McDonalds giving out toys so people buy their burgers, and I’m just wondering: Isn’t nature enough?

OWYANG: You know, I guess, just seeing something tangible, like a set of binoculars, like, ‘Wow! I earned that!’ is sometimes the icing on the cake. And it’s interesting that they found in another study that the kids that are out in nature, for every hour that they’re out, they probably have an extra 27 minutes of fairly vigorous exercise. Even though you’re not telling them, ‘Go and run a mile’ or ‘Go and play basketball,’ they end up just being kids.

Beyond that, there’s even mental health benefits where they’ve found that there’s been studies that show that ADD and ADHD symptoms can be reduced and that the nature, and being outdoors and being near green areas, can really decrease impulsivity, and also increase your attention span.

GELLERMAN: I wonder if virtual nature works as well. I was in the gym the other day and they have a new indoor bike. And it has a video screen, and you’re actually biking in the scene.

OWYANG: Your hunch is correct…that seeing nature on a screen has helped too. So, there have been some studies where they have put people on a treadmill and made them exercise, and they showed them green scenes, where they were in a rural, pleasant environment - and they found that there was a significant improvement in the positive effect of their moods, so it does definitely help mood and blood pressure.

GELLERMAN: So, Dr. Owyang, I gotta ask you: Do you practice what you prescribe?

OWYANG: Oh my goodness, absolutely. For me, I didn’t grow up in a place where I was always allowed to go out and run around in nature, and as I raise my own two children – I have a five-year-old and a one-and-a-half-year-old – and as I bring them out to the Bay, or to the different tide pools, or to see the giant sequoias, I notice that the kids are so much less whiny, I find I’m in a better mood, I find the kids eat so much better. So, it’s really terrific to see that in my own children and in myself.

GELLERMAN: Thanks so very much, I really appreciate it, Dr. Owyang.

OWYANG: My pleasure, my pleasure!

GELLERMAN: Pediatrician Charles Owyang writes prescriptions for nature in his Bay Area office at Kaiser Permanente.

Related links:

- Children and Nature Initiative

- CDC Childhood Obesity Facts

[MUSIC: Brian Blade: “Nature’s Law†from Mama Rosa (Verve music Group 2009)]

Sea Otters at Bay

Otter Pauses. (Photo: Salt Marsh Diary ©)

GELLERMAN: Well, just down the road from where Dr. Owyang hangs his shingle is the Elkhorn Slough. The nature reserve is a jewel of the California coastline are one of the top biodiversity hotspots in the world and home to a large population of playful sea otters.

A female sea otter eats a clam. (Photo: Salt Marsh Diary ©)

But for fisherman in the area, the otters are anything but fun and games. The furry food competitors can eat a quarter of their weight in shellfish a day. Though, as writer Mark Seth Lender sees it, what otters remove from the sea they more than make up by what they give back.

LENDER: Sea Otter, floating flat on his back, feet straight out at a slightly knock-kneed angle, paws folded on his chest like Charlie Chaplin at his silent best. Rafting together with all the others, he lazes into the hazy morning shift, in sixes and eights, fours and fives and a dozen. Then buoyant as butter, all drift apart. Sea Otter, that fur bundle, soft and wet and lumpy as a bag of spuds.

(Photo: Salt Marsh Diary ©)

As the warmth of the morning paints the bay, otters rub their eyes awake and begin their ablutions. Old boys dignified of demeanor, widely mustachioed under the nose like the off-white foam of an oversized cappuccino. Subadults, a sophomore class not yet mature enough to sport mustaches of their own. Semi-delinquent juveniles, rambunctious, rough-wrestling the peace and quiet into turbulent foam. No one seems to mind - it is not discipline but clean that is Otter’s credo.

Paws scrub and brush with great dexterity. Even behind the ears and in them, legs and backs and bellies, and under the chin. Arms and elbows, noses and the webbing between the toes. Formidable teeth are flossed bright by fingers brushing like toothbrushes. From the back of the neck to those broad hind feet chewed in the mouth like mukluk leather, not a centimeter is neglected.

In water hovering near 40 degrees, even with the thickest coat known to Nature, after a few hours an otter starts to freeze. The need to maintain body heat fuels an otter’s hunger, and throughout the day drives him to dive in forests of green kelp and golden water, there to wrest his dinner from the bottom of the sea.

Sea Otter bobs to the surface with his breakfast. With the most ancient of tools - the anvil stone balanced on his belly and the hammer of his arms - he will part any shellfish from its flesh. Each otter is a specialist, some preferring crabs, others eating only sea urchins. Many take only sea clams, broad as a hat brim, quickly cracked open, chewed and swallowed, then down again for more.

Kelp, the source of all this richness owes its life to Sea Otter. Without him, urchins multiply unrestrained, consuming everything, ruling again where they have not ruled in four hundred million years. Even the kelp disappears, forcing evolution back from where it came. If the otter dies out, the past becomes the present - a time and place in which humanity played no part, transformed into a future you don’t want to know.

[SEA OTTERS CALLING]

GELLERMAN: Mark Seth Lender’s new book Salt Marsh Diary, a collection of his wildlife essays will soon be published by St. Martin’s Press. To see Mark’s photos and video of sea otters at Elkhorn Slough, surf over to our website loe dot org.

Related links:

- Back Story: Listen to a short interview with Mark Seth Lender about his trip to Elkhorn Slough in California to see Sea Otters.

- Sea Otter Studies at USGS Western Ecological Research Center

- Salt Marsh Diary

The Language of Landscape

Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape, edited by Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney. (Courtesy of Trinity University Press)

GELLERMAN: By the way - if you're wondering what a "slough†(spelled S-L-O-U-G-H) is, we have a definition for you.

[Daniel Lanois “ O Marie†from Acadie (Red Floor Records 2008).]

The definition comes from the book “Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape,†edited by Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney. Writer Donna Seaman has this explanation of the term "slough."

SEAMEN: Slough. A slough - or a “sloe†- is a narrow stretch of sluggish water in a river channel inlet or pond. A slough can also be a marsh, swamp, bayou or any soft, muddy or waterlogged ground. The great, flat city of Chicago is built on filled sloughs or swampy bottomland. Slough is also a verb, meaning to mire in a slough or swamp. And to be sloughed can mean lost in a swamp.

Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape, edited by Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney. (Courtesy of Trinity University Press)

Used as slang - to “slough in†or “slough up†is to arrest or imprison, to be inhibited or bogged down. 19th century travelers reported horses sinking up to their necks in sloughs that look no deeper than a puddle. Prairies, especially those radiating from the Mississippi, are, or were, riddled with sloughs; and sloughs run along the St. Paul, Pacific and Sioux City Railroad tracks, and other elevated rights-of-way, providing ideal homes for muskrats.

GELLERMAN: Writer Donna Seaman calls "the beautiful Hudson Valley in New York State" her home ground. Her definition of slough came from the book “Home Ground,†edited by Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney.

Related link:

The Home Ground Project

[MUSIC: Vitamin Piano Series: “The End Of The World†from The Piano tribute To the Cure: Lovesong (Vitamin Records 2005).]

GELLERMAN: Just ahead - when your kids ask, ‘What did you do about global warming?’- how are you going to answer? Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for the environmental health desk at Living on Earth comes from the Cedar Tree Foundation. Support also comes from the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund for coverage of population and the environment. And, from Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is Living on Earth on PRI – Public Radio International.

Generation Hot

Mark Hertsgaard with his daughter, Chiara, a member of what he calls, “generation hot.†(Photograph by Francesca Vietor, Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

GELLERMAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bruce Gellerman. Being a parent these days is tough. There's a lot to worry about: Will my kids get jobs, can we afford their education? And now: How will climate change affect their future? Until journalist Mark Hertsgaard became a dad, he didn’t take this global issue personally. Now he does.

His new book, "Hot: Living Through the Next Fifty Years on Earth," tells the story of a new father's attempt to come to terms with his fears and his hopes for the future. Mark Hertsgaard talked about his book with Living on Earth's Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: Now you've been covering the climate beat for…well, as long as I’ve known you - at least 20 years, if not more.

HERTSGAARD: Yeah, I had been covering it for 15 years by the time she was born, so now it’s up to 20.

CURWOOD: And so, how did the story of climate change change when you became a father?

Mark Hertsgaard and the Climate Cranks from Mark Hertsgaard on Vimeo.

HERTSGAARD: Well the irony is that the birth of my daughter coincided with a major paradigm shift in the climate story, in the climate problem. What changed, sometime around the turn of the century, was that global warming triggered outright climate change, and it did so a hundred years sooner than scientists expected. And so that huge shift in the problem – the fact that now we’re locked into a significant amount of climate change, even if we do everything right – that is a major paradigm shift, and it happened to coincide with the birth of my daughter.

CURWOOD: So, when your daughter is old enough to understand, how will you explain climate change to her?

HERTSGAARD: Well luckily, I haven’t had to cross that bridge yet; it’s obviously a question I think about a lot. She is not quite six. She has a good grasp of general ecological principles already and the importance of not cutting down trees, for example, and keeping our water fresh, and our air clean and safe. And she understands that much about global warming and climate change, even at this age.

But, eventually, I hope that I’ll be able to talk to her in a child-appropriate, age-appropriate version of what I’ve written in this book, “Hot,†which is, on the one hand, being honest about the science and the science is pretty dark, but at the same time being equally honest about the many reasons for hope.

CURWOOD: Mark, let’s talk about what gives you hope here. And perhaps we could start with an example from your part of the world, the west coast of the U.S., King County there in Washington.

HERTSGAARD: You’re right Steve, I focused on solutions in this book. One of the most exciting solutions that I came across, certainly here within the borders of the United States, takes place in Seattle, King County, Washington. And it’s due to an amazing political leader there named Ron Sims, who served three terms as the chief executive officer of King County, which includes the headquarters of such massive firms as Microsoft and Starbucks and Amazon - Boeing has a large operation there. So a very business-friendly place, but also a place that is going to be powerfully impacted by climate change.

So what has Ron Sims done there at King County? He had all of his staff, all 13,000 people who work there have been told: ‘Ask the climate question.’ And what that means is to think out to the year 2050, ask climate scientists, ‘What will be the climate conditions facing the Pacific Northwest?’ And then, work backwards from that knowledge to today to figure out what we need to prepare for that. And so, for example, I visited a place called Green River, south of Seattle, where a levee breech there would cost the local economy 46 million dollars a day in lost supplies and services.

And by making that economic argument, Ron Sims was able to convince people that we need to strengthen these levees. And perhaps the most astonishing thing about this – I went to see some of these repairs – is that Ron Sims raised taxes in order to strengthen these levees. Not only did he raise taxes, but he got re-elected after he did it. Now in much of America that will seem pretty bizarre that a politician actually got away with raising taxes.

And yet, the reason that he was able to do that was that he explained to the local business people and the local townships and the local governments that if we don’t strengthen these levees, we’re going to have here what we saw in New Orleans, a local economy absolutely devastated by extreme weather.

CURWOOD: Now it’s not just politicians who make tough decisions and get the consent of the government to work on adaptation. As an example you cite in your book folks in West Africa make some… well they have some wonderful, low-tech sustainable farming practices there. Perhaps you could tell us.

HERTSGAARD: To me, that was the single most hopeful story in this entire book Steve. Here you’ve got some of the poorest people on the planet – illiterate farmers in Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, who are, even though they don’t know the term climate change, they have been adapting to it. And what they’ve been doing is so simple and ingenious – they are allowing trees to grow as they sprout, amidst their fields of millet and sorghum.

And, the reason it works is that when you’ve got little bushes and trees in your fields, they provide shade, which lowers the temperature and helps the plants to grow, but more importantly - the scientists told me - are the root systems that go down into the earth. Those trees’ roots systems go down into the earth - they ventilate the soil. That means that when there is rainfall, that the rain soaks into the earth rather then flashing off into creeks and disappearing.

And, literally, the underground water tables have been rising in these areas. We’re seeing doubling and even tripling of the crop yields, and by far the most gratifying result, we’re seeing that child malnutrition rates in these areas are plummeting. It’s really such a remarkable success story. And to me, for those of us living in the United States, it shows that if some of the poorest people can do that much to adapt in those kinds of extreme circumstances, surely the rest of us can do our share.

CURWOOD: Now throughout this book, you ask yourself, where will your daughter Chiara be able to best survive in the next 50 years. How much do you think about that question and what do you have for an answer for it?

HERTSGAARD: Oh, I think about that question a lot. I got started a little late, as a father, so it is very possible that when she is of an age to decide for herself where she will live, that I might not be there to advise her. And so, actually at the end of the book, I write her a letter that she will be able to open on her 15th birthday in the year 2020, and hopefully she’ll be reading the book then and look at the various places I’ve thought about where she might live.

But, I’ve also been a dad long enough to know, as I’m sure you do too, Steve, that what dad says is not always what child does, and she will probably decide for herself where to live. And I say that the one piece of advice in the letter that I write to her: Try to find a place that has a secure water supply, that has a functioning government, and above all, our best hope going forward is going to be tightly knit communities of people who work together, and I trust that my daughter will make a very good choice when that time comes.

Mark Hertsgaard with his daughter, Chiara, a member of what he calls, “generation hot.†(Photograph by Francesca Vietor, Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

CURWOOD: You know, as a dad myself, there is great power in what you put forth - how much do you think this dad force can be channeled to wake up folks who continue to be in denial.

HERTSGAARD: So, I’m hoping that this book will, in fact, help both dads and moms, and grandparents, and uncles and aunts, and all of us who have young people in our lives who we love, to say, ‘We aren’t really doing what we can on this problem.’ All of us who are conscientious parents, we think about giving our kids proper food and protecting them from bullies and when they scrape their knee, we gather them into our arms and comfort them. Well, climate change threatens far, far worse damages than any of that. Fighting climate change is now part of the parent’s job description.

CURWOOD: Hey Mark, before you go, could you read a bit of what you wrote to your daughter?

HERTSGAARD: Yeah, I write her a letter and I say at the end: ‘At this point, my precious, beautiful daughter, all that’s clear is that our civilization is entering a storm. There is no way around it, we have to go through it. We have to be brave, resourceful, and never give up. I would give my life to see you safe on the other side. With more love than I can say, Daddy.’

[MUSIC: Omar Sosa “Innocence†from Calma (OTA Records 2011).]

GELLERMAN: That’s journalist Mark Hertsgaard reading a letter to his daughter Chiara from his new book, "Hot: Living Through the Next Fifty Years on Earth.†He spoke with Living on Earth's Steve Curwood.

Related link:

Find out more about Mark Hertsgaard and his work at

Botanical Books

(Photo: Laurie Sanders)

GELLERMAN: This year spring will have officially sprung at precisely 7:21 pm eastern daylight time, on March the 20th. It's the equinox. And all things being equal, in the northern hemisphere, it's a time for gardeners to green thumb through catalogues and dream of plots to plant the season. Nothing new under the sun there, for it was back in the 15th century that the first botanical books were printed and began sowing inspiration. Producer Laurie Sanders digs back into their roots.

SANDERS: There are hundreds of books on the market about plants: identification guides, gardening manuals, wild plant medicinal handbooks. Here at Smith College, in the Rare Book Room, you can get a glimpse at how today’s plant books evolved by studying their predecessors.

[CASE OPENING]

SANDERS: The college’s collection includes some of the world’s earliest botanical books, known in their day as herbals.

[KEY OPENING AND DOOR SOUND]

ANTONETTI: In this case, we have the early printed books, books printed before 1500.

SANDERS: Martin Antonetti is the director of the Rare Book Room at Smith College.

ANTONETTI: Now we’re looking for the herbal by Leonard Fuchs. Here it is. It is big and heavy.

[BOOK SOUND]

SANDERS: In a few minutes, Antonetti and his colleague, John Burk, a professor of botany here at Smith, have pulled out half a dozen botanical books. Burk says these few books tell the story of how botanical illustration and literature changed and developed over a 1,500-year period. He picks up the oldest one, which was printed in 1454.

BURK: The printing press was invented in 1450, I believe, so this is one of the books from the first 50 years of printing. It has taken what were medieval drawings and transcribed these on to woodcuts and then used them to illustrate text here. It’s interesting as I just look through here, this is a drawing of a lily for example, and I think, you know, knowing a lily, you know, you can pretty much see what that is.

SANDERS: The drawings are very simple, almost cartoonish. Antonetti says that’s because in the 1500s, scholars were still relying on ancient texts as authorities. In the case of this particular book, the text was first written in 50 AD by an herbalist named Dioscorides. Antonetti says the original work never left circulation, but was hand-copied until the printing press was invented.

ANTONETTI: That explains why the illustrations are so schematic because they have been copied over and over and over again for those 1400 years. And over time, all of the detail, whatever there was in Dioscorides’ original pictures, has been stripped out. But this is the last period in which this occurs. Soon after that, everything changes.

SANDERS: The period we now know as the Renaissance was beginning. Art, culture, and science were transformed. And people who were writing herbals began to study the natural world firsthand, relying on close, personal observation rather than copying the work of somebody else.

The impact of those changes is obvious in the next book - the Brunfels herbal. It was printed in 1531, and Burk says it changed botanical illustration forever. In fact, it’s still a measure against which today’s botanical illustrations are compared.

ANTONETTI: These are real plants drawn from nature. Somebody has dug up the plant, and they have dug them up because you can see the roots. And what they actually do is make a watercolor painting of this and then transcribe that to the woodcut. And just look at this borage plant, which has actually the little hairs on the leaf of the borage. And he depicts this extremely well.

SANDERS: Aside from the extraordinary detail in the Brunfels herbal, the illustrations also, for the first time, show different stages of the plant’s life. There are flowers and fruits in the same drawing, sometimes even with dead or dying leaves. And during the next two decades, there are other important changes.

[FLIPPING OF PAGES]

SANDERS: The next herbal Burk leafs through includes similarly detailed plant illustrations, but now some of the drawings have been accurately colored - handpainted by professional watercolor artists. And the herbalist, Leonard Fuchs, included plants from the New World.

ANTONETTI: The Fuchs herbal is the first in which we start seeing plants that have actually come into cultivation since 1492 - plants that have been brought to Europe and have begun to spread. This is famous because it has the first drawings of Zea mays, what we call corn.

SANDERS: During the 16th century, interest in herbals and in fact all aspects of science flourished. Authors wrote not in Latin but in their native languages. In 1597 the first herbal in English was published. Each plant had a section called “virtues,†which described what could be done with the root or the flower, or what happened if you boiled it or ate the seeds.

SANDERS: Burk says the herbal by John Gerard was hugely influential.

[FLIPPING PAGES]

BURK: I’m just off the top of my head looking at hops. And he said, “the many virtues of hops do manifestly argue the wholesomeness of beer above ale. For the hops rather make it a physical drink to keep the body in health rather than an ordinary drink for the quenching of our thirst.†Rather nice ideas here.

SANDERS: Among those relying on the Gerard herbal were members of the Jamestown colony, and later the Puritans who settled in New England. But by the end of the 1700s, the age of the great herbals was over. Plant books were no longer huge compendiums, but focused on specific topics: plants and medicine, plant taxonomy, agriculture. Antonetti says there were also whole new fields of interest that developed.

ANTONETTI: After the age of the great herbal, you have the development of another genre of book dealing with plants, with flowers in particular, called floreography, which is what we call the language of flowers: illustrations of flowers and then descriptions of their emotional meanings. So if I were to give you a petunia, what would I really be saying to you? (Laughs.)

SANDERS: Considering a gift of petunias can mean anger or resentment, I’m glad he held off. For Living on Earth, I’m Laurie Sanders.

GELLERMAN: For a slide show of illustrations from Smith College's rare botanical books and herbals - dig a path to our web site loe dot org.

Related link:

Smith College Mortimer Rare Book Room

GELLERMAN: On the next Living on Earth – discovering new worlds within worlds when you get down and dirty with lichen.

PRINGLE: So when you look at a lichen, when you’re walking by, it’s not just an individual - it’s an entire ecosystem, sort of like a tropical rainforest in miniature, just maybe the size of the palm of your hand.

GELLERMAN: Close encounters…of the fungus kind, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: The Crusaders “Ballad For Joe (Louis) from Southern Comfort (Verve Music Group 1974).]

GELLERMAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, Mitra Taj, and Jeff Young, with help from Sarah Calkins, Sammy Sousa, Nora Doyle-Burr and Honah Liles. Our interns are Sean Faulk and Wynn Tucker. We had engineering help this week from Dana Chisholm. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE dot org - and while you're online, check out our sister program, Planet Harmony. Planet Harmony welcomes all and pays special attention to stories affecting communities of color. Log on and join the discussion at my planet harmony dot com. And don’t forget to check out our LOE facebook page. It’s PRI’s Living on Earth. Steve Curwood is our executive producer. I'm Bruce Gellerman. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science

Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield Farm, organic

yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth

hormones on their cows. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from

you, our listeners, The Ford Foundation, The Town Creek Foundation, The Oak

Foundation supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues. And Pax

World Mutual Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors

into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at pax world dot com.

Pax world, for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI – Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth