December 14, 2012

Air Date: December 14, 2012

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Farm Bill and the Fiscal Cliff

View the page for this story

Congress and the White House are scrambling to find savings big enough to avert the broad cuts mandated by Congress, known as the Fiscal Cliff. Substantial savings could possibly come from the Farm Bill, as both House and Senate Agriculture Committees have proposed legislation that they claim would save billions. But critics on the left and right say it would cost more than it would save. Host Steve Curwood talks about the Farm Bill with Scott Faber, Vice President of Government Affairs for the Environmental Working Group. (06:00)

Machine Tenderized Beef

View the page for this story

To make cheaper cuts of beef less tough, processors mechanically tenderize it with small needles or blades. Sarah Klein from the Center for Science in the Public Interest worries that the practice can insert dangerous pathogens like E-coli into the interior of the meat. But Auburn University professor of meat science, Christy Bratcher tells host Steve Curwood that mechanically tenderized beef is safe as long as it is cooked to appropriate temperatures. (08:30)

Turtle Rescue / Emmett FitzGerald

View the page for this story

Every fall, hundreds of hypothermic sea turtles wash up on Cape Cod beaches, caught by tides, winds and cold water. This year more turtles have been stranded then ever before, though scientists aren’t sure why. But thanks to volunteers at the Massachusetts Audubon society and the New England Aquarium, many threatened turtles will be rescued, rehabilitated, and released. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald reports. (08:00)

Oil Spills in Nigeria

View the page for this story

The West African country of Nigeria is one of the top oil producing countries in the world. Reuters reporter Tim Cocks tells host Steve Curwood that oil theft and lack of enforcement of environmental laws have resulted in ongoing oil pollution and frequent spills, including a recent spill by Exxon Mobil that is 20 miles long and affecting fishing. (06:30)

BirdNote ® Spruce Grouse

View the page for this story

A chicken-like bird living in the boreal forest south of the arctic, the Spruce Grouse, survives the cold winter by eating nothing but pine needles. Michael Stein reports. (02:00)

Birthright

View the page for this story

Though many people now live in an urban environment, Dr. Stephen Kellert says it’s essential to human wellbeing to make sure we still incorporate nature into our everyday lives. Steve Curwood talks with Stephen Kellert, Professor Emeritus of Social Ecology and a Senior Research Scholar at the Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, about his new book, Birthright. (10:30)

The Place Where You Live

View the page for this story

Writer Linda Hasselstrom lives and writes on the South Dakota Prarie. It's a beautiful place that commands deep respect when the winter cold and snow arrive. (04:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Scott Faber, Sarah Klein, Christy Bratcher, Tim Cocks, Stephen Kellert

REPORTERS: Emmett FitzGerald, Michael Stein, Linda Hasselstorm

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. As Washington teeters on the brink of draconian cuts, some suggest that the massive Farm Bill, that covers forests, food, farms and conservation should be folded into legislation to fix the fiscal cliff – but others say not so fast:

FABER: It sort of boggles the mind that we would put a bill that would commit the government to spending a trillion dollars into another piece of legislation that's ostensibly designed to right the nation's finances - but that's exactly what some are proposing.

CURWOOD: Also – saving critically endangered turtles who get caught in the cold of Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

LECASSE: To our knowledge this phenomenon of a mass stranding of hypothermic sea turtles on an annual basis, this is the only place in the world that we know it happens at this scale.

CURWOOD: We'll have these stories and a visit to the place where you live this week, on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[THEME]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm.

The Farm Bill and the Fiscal Cliff

House Committee on Agriculture. (Photo: http://agriculture.house.gov)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. As Washington squares off over the budget impasse known as the fiscal cliff, a compromise may involve the Farm Bill. Both the House and Senate Committees on Agriculture have proposed measures to slash billions. But a deal to bring the Farm Bill as a rider to a last minute tax and spend package has drawn sharp criticism from left and right.

The conservative Heritage Foundation calls farm subsidies “the nation’s largest corporate welfare program”, and similar warnings come from Scott Faber of the progressive Environmental Working Group.

FABER: The Farm Bill is a trillion dollar bill that not only provides subsidies to farmers, but also provides conservation payments to farmers that are offering to help save the environment. It helps feed the hungry, it invests in research, renewable energy, it will cost more than the Affordable Care Act over 10 years. There is no one piece of legislation that will have a bigger impact on what we eat and how it’s grown.

Scott Faber, Vice President of Government Affairs for the Environmental Working Group. (Photo: EWG)

CURWOOD: The Farm Bill legislation appears to be a bipartisan process this year. There’s a proposal from the Senate committee on agriculture, one from the House. Let’s talk about them - first, what’s in the House measure?

FABER: Well, the House measure is just one of the worst pieces of farm and food legislation in decades. It cuts food stamps dramatically, it cuts funding for environmental programs, and it uses those savings to give the most successful farm businesses a huge raise at a time when farmers are enjoying record income and seeing the value of their land reach levels that many of them never could have imagined.

CURWOOD: Now, at what point is the House bill? Is this something that the whole House has considered and brought forward? Ready to deal with the Senate? Or does it have some more work to be done?

FABER: No, the House bill, the bill produced by the Agriculture Committee has not reached the House floor, in part because the leadership of the House was not confident that it could get the votes to pass. It’s really incredibly important that a bill produced by this particular committee reaches the floor because the House Agriculture Committee, probably not surprisingly, is dominated by representatives from districts that collect the lion's share of farm subsidies.

Farm. (Photo: bigstockphoto.com)

And fortunately, the authors of the bill would very much like to bypass floor debate. It kind of boggles the mind that we’d put a bill to commit the government to spending a trillion dollars into another piece of legislation that’s ostensibly designed to right the nation’s finances, but that’s exactly what some are proposing.

CURWOOD: What’s in the Senate Farm Bill, as proposed by chairman Debbie Stabanow from Michigan?

Chicken Farm. (Photo: bigstockphoto.com)

FABER: The Senate bill is much better than the House bill. The bill does not cut food stamps nearly as much as the House, the bill does not cut subsidies nearly as much. But many of the reforms that would ultimately be included in the final bill would only come from a full-fledged debate on the floor of the House where members are not beholden to only the representatives of the most successful farmers.

CURWOOD: Now, the House bill, under the leadership of Chairman Frank Lucas of Oklahoma, says it would save $35 billion dollars. The Senate measure, I gather, would save $23 billion dollars. What are these savings coming from?

Frank D. Lucas, Republican Representative from Oklahoma and Chairman of the House Committee on Agriculture. (Photo: http://agriculture.house.gov/)

FABER: Well, unfortunately almost half of the savings in the House bill come from cutting food stamps or from what’s now called the Supplemental Nutrition and Food Program, or SNAP, at a time when hungry families are really struggling. The savings that are predicted are really an illusion because of the ways they’ve designed the new subsidy programs. In particular what they’ve done is they’ve included some price guarantees for the major commodity crops like corn, soy beans, wheat, cotton, rice and so on, that may not appear to cost much according to the Congressional budget office, but could cost the taxpayers tens of billions, even hundreds of billions of dollars, over the next ten years if the price of these major commodities fall, even modestly.

So there’s quite a lot of budget gimmickry associated with those savings. The long-term costs, the real costs to tax payers of the House bill will be far greater than CBO estimates.

Debbie Stabenow, Democratic Senator from Michigan, Chairwoman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry. (Photo: http://www.ag.senate.gov)

CURWOOD: The Congressional Budget Office. So, I understand that both measures include cutting conservation programs.

FABER: Both measures cut conservation programs, which is very disappointing. Just in the last four years, we’ve seen more than 23 million acres of wetlands and grasslands plowed up to produce corn and other crops. That’s an area the size of Indiana. What’s more, there’s new studies out that say about 80 thousand miles of rivers and streams are still too polluted to meet the basic goals of the Clean Water Act. And in most cases, agriculture runoff is the primary culprit. So, to cut those programs, the only safety net we have for the environment, is really disappointing in light of what’s going on, on the landscape.

CURWOOD: What’s in either version of this farm legislation that will help farmers cope with the extent of the drought that we have now in this country?

FABER: There’s already in place, through what’s called government subsidized crop insurance, an incredibly generous program that allows farmers not only to insure against losses and yields, but against losses in business revenue. And so in places like Iowa and Illinois and Indiana, Nebraska, where we’ve seen this terrible drought, the vast majority of farmers, more than 80 percent, in some cases more than 90 percent, have purchased government subsidized insurance. And by and large, farmers who grow major commodities have an incredibly generous system of protection.

CURWOOD: Now, some people would say the Environmental Working Group, where you’re Vice President of Government Affairs, is a progressive or a liberal organization… in your view, what are the conservative objections to these farm bills as proposed?

FABER: We’ve worked with many groups from the right including the Heritage Foundation, American Enterprise Institute, Americans for Prosperity, terrific fiscal leaders who, like the Environmental Working Group, believe that there are significantly more savings to be found if we really reform farm subsidy programs. Especially in light of the fact that the household income of a real farm, a large commercial farm, is well above $200,000 dollars a year. Now, these are the sorts of people who shouldn’t be getting subsidies; these are the sorts of people who should perhaps be the subject of some some tax increases.

CURWOOD: Scott Faber is Vice President of Government Affairs for the Environmental Working Group in Washington. Thank you so much, Scott.

FABER: Thank you!

Related links:

- Information on the new farm bill proposed by the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry

- Information on the new farm bill proposed by the House Committee on Agriculture

- The Heritage Foundation info on the Farm Bill

- The Environmental Working group’s info on agriculture

- “No Secret Farm Bill in Fiscal Cliff Deal.” Press Release from the Environmental Working Group

- More about Scott Faber

Machine Tenderized Beef

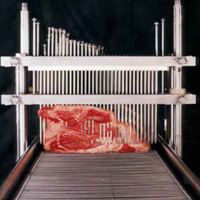

Some research suggests that up to 90% of beef sold in the US has been mechanically tenderized. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: By the way, dairy and meat farmers get little or no federal subsidies… and drought can make for a tough beef market. And talking of tough - the Kansas City Star recently investigated mechanically tenderized beef. A year-long probe of the practice found it's pervasive throughout the American beef market.

And while it may improve the texture, mechanical tenderizing can create a hidden host for life-threatening pathogens. Sarah Klein is a Senior Food Safety Attorney at Center for Science in the Public Interest.

KLEIN: You know, many of us think of tenderizing as something you used to do in your kitchen with a mallet, but the process that they have now is not at all like that. We’re talking about hundreds if not thousands of tiny little needles or blades, very very small, making a bunch of teeny tiny little incisions into the meat. It’s supposed to make it a little more tender, as the name suggests. Meat today is a little more tougher because of the way we’re raising cattle.

The life-cycle has been compressed and we’re giving animals growth promotants so that we can pack more meat on them in a shorter period of time. And the theory is that that makes the meat tougher in the end. So, the beef industry has found a way to tenderize the meat rather than changing the raising practice.

CURWOOD: Why is mechanically tenderized beef more dangerous than beef not tenderized in a mechanical fashion?

KLEIN: Typically, the pathogens that we’re concerned about with beef… they exist on the hide of the animal, they come in the form of manure, and they’re transferred to the interior of the animal during processing. Sometimes the bacteria become aerosolized or bits of the manure will fly onto the carcass. Those things get trimmed off into steaks. And if you left that steak alone when you cooked it, you’d almost always sear off that contamination even if you left the interior of that steak rare or medium rare.

But once you use those needles or blades, and you push the pathogens that are on the exterior of the animal down inside the meat, now you’ve basically turned your steak into a bit of ground beef, and that means that you’d have to cook it thoroughly in order to ensure that the pathogens that are now inside the meat get cooked out.

CURWOOD: What are the pathogens that you’re concerned about here?

KLEIN: We’re primarily concerned about E.coli. These are pathogens that don’t cause generally a mild gastrointestinal illness, the kind of thing, you know, where you stay home for a couple of days with diarrhea, these are serious, serious food borne illness that can result in everything from kidney failure, long term consequences like arthritis, or even paralysis or death.

CURWOOD: How many people do you think come down with these afflictions from eating beef in the United States in a given year?

A typical blade tenderizer like this breaks down muscle fibers and connective tissues. (American Meat Institute)

KLEIN: It’s hard to know exactly because the way that we report foodborne illness to the Centers for Disease Control means that all we know is kind of just the tip of the tip of the iceberg. What we do know is 48 million Americans are getting sick from foodborne illness every year. 3,000 American are dying every year. It’s hard to know exactly how many are those are attributed to beef, but we know that the number is not insignificant.

CURWOOD: So, there I am now, I’m looking at my organically-fed, grass-fed beef. Am I running the risk of… if I were to bite into that… of having it been mechanically tenderized?

KLEIN: Yes. I think it’s important for consumers to know that organic and grass-fed are judgments of humane treatment. They’re judgments of the antibiotic use that has gone into the production of that animal. They are not themselves indicators of any greater safety protection from acute illness.

CURWOOD: Please give me an estimate of how much of beef consumed in the US has been mechanically tenderized, and where a consumer might be most likely to run into it.

KLEIN: Unfortunately it’s difficult to know how widespread this process is. Some estimated it could be as much as 90 percent of the intact product that’s sold in the US, is not intact, that it to say that it’s been tenderized or blade tenderized in some way. I think it’s fair to say that any time a consumer is eating steak – whether they’re eating it in a restaurant, in a cafeteria, in a hotel, or in their own kitchen where they purchased a piece of meat from the grocery store, it is highly possible that that meat has been needle tenderized. Because there’s no labeling, there’s really no way for a consumer to know.

CURWOOD: So, as I understand it now in this conversation, you’re saying that the vast majority of beef in this country has been mechanically tenderized but the US Department of Agriculture doesn’t require that beef producers label it as such, why is that?

KLEIN: USDA is actually now considering labeling. I think the Agency has finally come to recognize that this is a gaping loophole in food safety. An organization that works with the retail sector, that is with restaurants and grocery stores, has also asked for the labeling, so that their members can comply with rules that require them to cook ground beef products differently than steak products.

CURWOOD: So the vegetarian folks don’t have to worry about this, but what about those who do want to consume beef. What should be done, in your opinion, to make beef more safe for them?

KLEIN: The most important thing for consumers to do is to practice defensive eating. And that is make sure that you’re handling your meats carefully to avoid cross contamination, if your raw meats are carrying pathogens you want to make sure that those don’t spread around your kitchen.

So, we don’t use the same cutting board for meats that we’re then going to use for raw produce items, and most importantly, cook your meat thoroughly using a meat thermometer. Check to make sure that it’s reached the correct internal temperature. It’s far better to adjust your palate to a more well-done meat then it is to suffer from a serious foodborne illness.

CURWOOD: Sarah Klein is a Senior Food Safety Attorney at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, in Washington. Thank you Sarah!

KLEIN: Thank you.

CURWOOD: We called up the American Meat Institute for their response to the Kansas City Star articles. They referred us to Christy Bratcher, an assistant professor of Meat Science at Auburn University in Alabama. Christy Bratcher, Welcome to Living on Earth.

BRATCHER: Hello.

CURWOOD: Now, can you estimate for me, just how much of the beef produced in the US has been mechanically tenderized?

BRATCHER: I don’t think I could put a percentage on that number. Typically a product that is going to go to restaurant that is a select or lower grade, is tenderized if it’s a steak cut.

CURWOOD: When it comes to beef, at the top is prime, and then there’s choice, and then there is select, before you get to the utility grades.

BRATCHER: Correct.

CURWOOD: How much of the select beef do you think there is proportionally in the US? Is this more than half, do you think, or three quarters?

BRATCHER: I would say maybe around half. We want to guarantee a tender beef product, and by doing this mechanical tenderization process to a select or lower grade, we can guarantee a tender product.

CURWOOD: How safe is the process of mechanical tenderization? There’ve been questions raised that it promotes the spread of E. coli if the meat isn’t properly cooked.

BRATCHER: You know, I don’t consider it a large problem at all. Obviously there have been recalls and serious illness of concern associated with mechanically tenderized beef. But those are very unfortunately incidences that happen on a very low incident occurrence. Those people have gotten sick and it has, you know, affected the rest of their lives or unfortunately people have lost small children to them, and those are horrible events that have happened. However, if we are cooking our beef to a safe temperature, you shouldn’t have problems with bacterial growth.

CURWOOD: Now, the Kansas City Star has published a series of articles that have looked into the beef industry. And they raised a number of concerns about mechanically tenderized beef – they say look, this creates a perfect host for E. coli and they pointed to cases where people had gotten sick. The Kansas City Star - overreacting in your view?

BRATCHER: You know, I believe that they are overreacting. I think they’re also doing a good job of trying to educate consumers, but I also think that they need to look a little bit deeper and get some scientific information before going out and trying to scare the general population about practices that are very safe within the meat industry and that has had a lot of research done to prove that they are safe.

CURWOOD: Cristy Bratcher is Assistant Professor of Meat Science at Auburn University in Alabama, thank you so much.

BRATCHER: Thank you for your time.

[MUSIC: Van Morrison “Pagan Heart” from Born To Sing: No Plan B (Blue Note Records 2012).]

CURWOOD: Just ahead – playing the good Samaritan to endangered turtles. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ravi Shankar – George Harrison: “Festivity & Joy” from Collaborations (Rhino Records 2010).(R.I.P. Ravi Shankar 04/04/1920 – 12/11/2012).]

Turtle Rescue

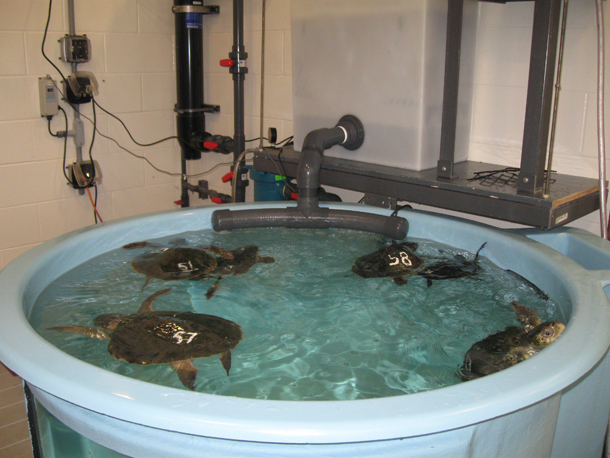

Tanks filled with turtles at the New England Aquarium’s Animal Care Center (photo: New England Aquarium)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Swimming season in New England ended weeks ago as it's just too cold. But the chilly water of late fall brings some special guests inside the arm of Cape Cod. Every November, sea turtles caught in the cold begin washing up on shore.

LECASSE: The north side of Cape Cod is formed like a big bucket. Turtles, when they get the instinct to swim south in the early autumn, that instinct is blocked by all this land.

CURWOOD: That’s Tony LeCasse of the New England Aquarium. For the past twenty years, the aquarium has been partnering with the Audubon Society to rescue turtles who become too cold and get stranded on the beach. This year, there are more of these hypothermic turtles than ever in need of help. Living on Earth's Emmett FitzGerald has our story.

[BEACH SOUNDS]

FITZGERALD: Each year in November, dozens of volunteers pull on hats, zip up their parkas, and tramp the beaches of Cape Cod from Sandwich to Truro. They head out just after high tide, sometimes in the dark, following the wrackline, where seaweed marks the water’s highest point. These hardy beachcombers are looking for turtles.

LACH: We are watching for that familiar sea turtle shape, about the size of a dinner plate, but with flippers.

FITZGERALD: Michael Lach and his nine-year-old son Skyler have been volunteering with the Massachusetts Audubon Society for four years now.

Volunteer Skyler Lach, age 5, handing hypothermic turtles on the beach in Cape Cod in 2008 (Photo: Michael Lach)

LACH: We asked if we could volunteer for their sea turtle rescue program and we were assigned to this very beach, Linnell Landing Beach, the next day. And what happened the next day? Who found the first turtle?

SKYLER LACH :I did!

LACH: You did that’s right.

SKYLER LACH: I was really excited when we found that first one.

FITZGERALD: They comb the beach in the evening, after Skyler gets out of school. When they spot a turtle, they set it above the tide line for the Audubon staff to collect.

SKYLER LACH: You try to find a marking, so that Audubon can see it better.

LACH: Something that really stands out on the beach so that when Audubon comes down to the beach to find and pick it up - they can locate it easily.

FITZGERALD: This year there have been more stranded turtles than ever before, but Skyler has only found a couple, and he's looking to add to his total.

SKYLER LACH: The most we’ve found in one year is six and we’re trying to beat that record. We’ve still got five more numbers to go because we’ve already found two. If we added our last three years up I’d say that’s about 14.

[BEACH SOUNDS CONTINUE]

FITZGERALD: Bundled up and armed with flashlights, Skyler and his dad head off into the night.

SKYLER LACH: Do you think we’re going to find any today?

LACH: I don’t know, we still have quite a bit of beach to walk.

SKYLER LACH: I think we have a pretty good chance of finding one because the NW wind, that’s the best wind for it, but the wrackline is a bit thin.

FITZGERALD: Massachusetts Audubon delivers all of the turtles that volunteers find to the New England Aquarium’s Animal Care Center in Quincy, Massachusetts.

[SOUND OF TRAIN]

FITZGERALD: The Animal Care Center is in an old brick building along the Quincy wharf. Freight trains wind between abandoned warehouses with smashed windows, and the smell of the sea is thick. Tony Lecasse let me into the Center.

[DOOR SOUND]

FITZGERALD: Inside the cavernous room are massive circular tanks like above-ground swimming pools. They are filled with threatened sea turtles—spotted Greens, large Loggerheads, and the most endangered sea turtle in the world, the Kemp’s Ridley.

Numbered turtles swim in a small tank at the Animal Care Center in Quincy (Photo: Michael Lach)

LECASSE: The predominate species and the most important one is these little Kemp’s Ridleys. They are everywhere from dinner plate size to serving platter size. The juvenile sea turtles are a charcoal black with a white serrated edge and they sort of have a heart-shaped shell.

FITZGERALD: As I peer over the edge of the tank, a turtle comes up for air.

[BREATH NOISE]

FITZGERALD: Tony says, don't get too close!

LECASSE: They’re cute little guys but you still gotta be careful with them. These guys primarily eat crabs, so if you stuck your finger in there, you might require some good stitches.

FITZGERALD: Every day, the Audubon Society delivers batches of turtles to the center in Quincy.

LECASSE: We had three days last week where we had more than 20 turtles come in at a time. To give you an idea of how unusual that is, sea turtle hospitals in Florida might see 20 sea turtles in a season.

FITZGERALD: This hospital can hold about 100 turtles at a time. If they get more than that, they have to offload them to other facilities up and down the East Coast. The center recently sent 35 turtles to Florida in a Coastguard plane.

A stunned loggerhead turtle being loaded into a plane bound for Georgia (Photo: New England Aquarium)

Tony says that scientists at the aquarium aren’t sure why so many turtles have stranded this year. It could be good news: the total population of turtles is recovering, and the number of hypothermic turtles is rising along with it. But climate change could be playing a role as well. Tony thinks that warm water temperatures last year might have confused the turtles, delaying their normal migration.

LECASSE: In 2011, we had water temperatures that were five and six degrees above normal for a good part of the year. And so the normal environmental cuing didn’t happen because the water was warm, and they probably thought they had more time.

FITZGERALD: When the turtles arrive at Quincy, they’re usually in pretty bad shape. They have often been floating in the bay for months, and have used up all of their fat reserves.

LECASSE: Normally there should be big rolls of fat like you’d see on a twelve month old baby coming off the thighs. But what will happen is that you will literally see a skinny leg with sort of draped skin over it, and that just indicates how dehydrated and how emaciated a lot of these turtles are.

FITZGERALD: First the hospital staff treat each turtle for hypothermia and dehydration. Unlike warm-blooded animals, these reptiles need to be rewarmed gradually, about five degrees a day, to prevent infections. Once a turtle is back on its flippers, it can be moved into one of the big tanks with the others. The staff paint a number on the back of every turtle’s shell with white nail polish, so they can keep track of each individual. One of the biggest challenges can be feeding.

CARLA: My job right now is to focus on number 28, he’s not eating.

FITZGERALD: Carla is a volunteer at the turtle hospital. She’s dangling a piece of herring in front of a small turtle with a white number 28 scrawled on its shell. Despite her efforts, 28 isn’t interested in the food.

CARLA: What we’re doing for 28 is we’re actually tube feeding him, which we don’t like to do, it’s stressful for the animal. So that’s why I need to work on him for at least a half an hour.

FITZGERALD:Feeding the turtles is an exact science, and the staff carefully monitor each individual’s food intake.

CARLA:We feed them squid and herring, and everything is weighed so we know exactly how much they’re eating.

FITZGERALD: Recent arrivals often struggle to eat solid food, and as Carla tries to coax these reluctant newcomers, healthier veterans sometimes get in the way.

CARLA:See number 55 he’s obviously hungry. So you’re trying to feed number 93 but…yes number 55 is hungry but I bet he’s already reached his capacity.

Head veterinarian Charles Ennis treats a loggerhead at the turtle hospital in Quincy (Photo: New England Aquarium)

FITZGERALD: Turtle rehabilitation takes a long time. Best-case scenario, a turtle will be out of the center in a couple of months, but some will require nearly a year of treatment. When the turtles are healthy, the aquarium transports them to warmer waters to be released.

LECASSE: If the turtle is ready to go in early January or February, we’ll arrange for the turtle to be flown down to Florida or Southern Georgia to be released down there. If the turtle is ready in March or April, we’ll bring that turtle down to the Carolinas. If they’re ready in the summer time we’ll release them off of the Cape or off of Martha’s Vineyard.

FITZGERALD: The New England Aquarium and Wellfleet Audubon have been rescuing turtles for twenty years now, and they’re proud of their record.

Stunned loggerheads being transported from Cape Cod to Quincy (Photo: Michael Lach)

Stunned loggerheads being transported from Cape Cod to Quincy (Photo: Michael Lach)

LECASSE: If a turtle arrives alive here, it has a 90% chance of surviving and being released.

FITZGERALD: That’s thanks to biologists, veterinarians, and hundreds of committed volunteers, young and old. In the past twenty years, they have rescued, rehabilitated and released over a thousand sea turtles. For these critically endangered creatures, every effort counts. For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett FitzGerald.

CURWOOD: And thanks to Naomi Arenberg who helped report this story.

Related links:

- New England Aquarium: Marine Animal Rescue Team Blog

- Massachusetts Audubon info about sea turtles and their rescue

- New England Aquarium: Marine Animal Rescue Program

[MUSIC: Ravi Shankar – George Harrison “Love-Dance Ecstacy” from Collaborations (Rhino Records 2010).]

Oil Spills in Nigeria

Puddles of oil and water near the Rukpokwu-Rumueke oil pipeline. (Amnesty International)

CURWOOD: Nigeria produces roughly two million barrels of oil every day and is one of the largest exporters in the world. Yet the enforcement of environmental laws is lax in this West African nation, and oil spills are rife, though seldom reported. But a recent huge spill from an ExxonMobil facility is getting attention.

It has devastated fishing and apparently spread oil across perhaps 20 miles of water off shore from the Niger Delta. Tim Cocks, the chief correspondent for Reuters in Nigeria, joins us via Skype. He says the Exxon subsidiary in Nigeria has admitted responsibility and is working to clean up the mess.

COCKS: Exxon says that they are doing their very best to contain it. The last we know from them was sort of late last month when they said that, ‘we are using dispersants to try to contain it’ – they are doing their best to try to clean it up – and that the cause of the spill is still being investigated.

CURWOOD: Now there was a similar spill from an Exxon facility back in August… how does this one compare to the August spill?

COCKS: I’m actually a little on the spot here because we’ve had so many oil spills that you do start to forget which one is which and which one was bigger than which. Also, usually there isn’t very much information about the spill, the only way to find out is to go down there and see how far it’s spread.

This photo of a hand dipped in oil in Ikarama Bayelsa, Nigeria was taken eight months after an oil spill. (Amnesty International)

And even then it’s hard to get a very accurate picture because so much oil has been spilt, particularly on the onshore Niger Delta over the years, but you might get to a place where locals say this is the spill from the Exxon or Shell, and it’s impossible to tell whether that’s from that spill, or one that happened earlier.

We’re talking about something that happens very, very frequently. So whether this spill is worse than anything we’ve had for awhile, I really don’t know. I don’t think anyone knows exactly how many barrels were actually spilt in this.

CURWOOD: Now, why are these big spills so frequent there in Nigeria? Am I right to assume that the penalties for a spill in Nigeria don’t compare to the penalties for a spill, say, here in the United States?

COCKS: There are definitely penalties for oil spills. The issue is that they’re not generally enforced. There’s definitely this perception that the Nigerian government either can’t or won’t enforce any kind of punitive measures against the oil companies for spills. What this really does show is that the oil companies are not following best practice in Nigeria the way they would have to somewhere like the Gulf of Mexico, somewhere that if you spill oil like BP just discovered, it’s a whole load of trouble for you.

The main argument that the oil companies have for continuation oil spills on a regular basis is that it’s not really their fault, it’s the fault of oil thieves who hack into pipelines so that they can steal the oil and either refine it at the local market or sell it on ships going to be refined elsewhere or outside of the country.

Just to give you an idea of just how much oil is being stolen, the finance ministry came up with an estimate recently, is that something like a fifth of Nigeria’s oil is lost to theft. Putting it in context, that’s 400,000 barrels a day of oil being stolen. It is a major problem and it certainly is a major contributor to the spills.

CURWOOD: If 400,000 barrels of oil are being stolen everyday, that’s not exactly a mom and pop business, there must be enterprises that are dealing in this!

COCKS: It is a multi-billion dollar business. There’s complicity at all levels according to experts in this field. Complicity between the security forces and the oil thieves, between some local politicians, and possibly some politicians at the federal level, and between some international criminal networks because the vast majority of this oil isn’t refined local, or sold locally, it’s sold abroad.

The main networks have it refined in Singapore, which makes sense because it’s a major refining center – I think it’s the largest refining center in the world - and in the Balkans where you have criminal networks better known for things like trafficking sex workers and selling cigarettes. So, it is a huge international criminal enterprise.

CURWOOD: Have you seen an oil spill yourself there?

COCKS: Yes, I made a visit down to the Ogoniland region which is one of the worst affected by oil spills. Ogoniland is where Nigeria first discovered oil and where it first started pumping oil, more than 50 years ago. There were two major spills by Shell, which is the leading operator in Nigeria, I think around 2008. And Shell accepted responsibility for those spills – they didn’t try and say that it was oil thieves or anything.

The places that I saw, and we went out on a boat quite a long way… you could just see dead mangroves for miles around. These kind of blackened husks of mangrove trees, oil was absolutely everywhere, and we’re talking several years after the spill! And so whether it was just 4,000 barrels that Shell says was spilt, or whether it was more like what Amnesty International suggests, several hundred thousand barrels, it clearly had a very damaging impact. You know, there were fishermen out in the water and they’d come back with the few little fish that they had were covered in this rainbow covering of oil, clearly really struggling to make ends meet with the waters so thoroughly poisoned by this oil.

CURWOOD: How’s the wildlife faring with all of this oil?

COCKS: Well, the Niger Delta is a majorly important hub for wildlife. It’s a huge expanse of mangrove swamps and creeks, rainforest. When I was down there I could see herons and other birds like that water treading through what was effectively an oil slick. So, in terms of what the oil has done to the wildlife in the region, I’m not sure. I’m not even sure if anyone has done a comprehensive study.

CURWOOD: How has civil society in Nigeria responding to this epidemic of oil spills? Of course, famously, Ken Saro-Wiwa, speaking in protest about this, was ultimately executed for his efforts.

COCKS: The Ogoniland communities are still very much trying to keep that activism from that time alive. Of course, the problem is that they feel that no one is really listening to them.

CURWOOD: The statistics would say that Nigeria is one of the top 20 oil producing countries on the planet; what does that mean in terms of money for the people of Nigeria and for the Nigerian government?

COCKS: For the Nigerian government, it means that a huge cash register goes off everyday. Huge amounts of petro dollars pour into their treasury. What does it mean for the people? I think most Nigerians would say that it hasn’t meant very much except everything’s now very very expensive. Oil has been with Nigeria for many decades and most people don’t feel that they’ve really benefited from it. Most people feel that it’s going into the government coffers and lining people’s pockets.

CURWOOD: Tim Cocks is the Chief Correspondent for Reuters, based in Nigeria. Thanks so much, Tim!

COCKS: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Asked for comment, ExxonMobil's managing director for its Nigerian operations, Mark Ward, sent us an email assuring us that: "Mobil Producing Nigeria is committed to a speedy and comprehensive cleanup. Our oil spill response plans have been quickly implemented in line with this objective.”

Related link:

Reuters report on the ExxonMobil oil spill in Nigeria

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE® THEME]

BirdNote ® Spruce Grouse

A female Spruce Grouse. (Photo: © Todd and Conni Katke)

CURWOOD: Well, it's that time of year when the smell of fresh pine and spruce fills the air of many homes. And the conifers that get adorned for Christmas come from a stock of evergreens that makes it possible for one tough bird to survive. Here's Michael Stein with today's Birdnote®.

[WINTER WIND]

STEIN: In the boreal forest – the broad expanse of forest lying south of the Arctic – winter temperatures routinely drop to 30 below zero. [Chill, winter wind] Birds that spend the winter in this harsh domain of spruce, pine, and other conifers rely on remarkable adaptations in order to survive. The Spruce Grouse is one such bird. Most Spruce Grouse – rotund, chicken-like birds that weigh about a pound – remain here all year.

[SPRUCE GROUSE CLUCKING CALLS]

A Spruce Grouse on the ground. (Photo: © Todd and Conni Katke)

STEIN: In the snow-free summer, they forage on the ground, eating fresh greenery, insects, and berries. But in the snowy winter, the grouse live up in the trees, eating nothing but conifer needles. Lots and lots of needles.

[SPRUCE GROUSE CLUCKING CALLS]

STEIN: Simple enough, right? Just keep eating. But conifer needles are both low in protein, and tough to digest because they’re heavy in cellulose. To meet the energy demands of winter on needles alone, Spruce Grouse – this may seem hard to believe – grow a bigger digestive system. Their ventriculus – or gizzard – which grinds food, may enlarge by 75%. So remember the hardy Spruce Grouse this holiday season.

[SPRUCE GROUSE CLUCKING CALLS]

(Photo: © Todd and Connie Katke)

STEIN: As you stand back to admire a Christmas tree, somewhere in the northern forest a grouse is nibbling away at such a tree – one needle at a time. I’m Michael Stein.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Spruce Grouse [2389] recorded by H. Lumsden. Ambient created from Boreal Chickadee [77204] recorded by C.A. Marantz.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2012 Tune In to Nature.org December 2012 Narrator: Michael Stein

CURWOOD: There are some pictures of chubby Spruce Grouse over at our website - LOE dot org.

Related link:

BirdNote

[MUSIC: Tony Williams “Emergency” from Emergency (Polydor Records/Verve Music group 1969)(Happy Birthday Anthony Tillmon Williams 12/12/1945 – 02/27/1997).]

CURWOOD: Coming up… for humanity, it's as vital as breathing - or eating - or light. We need the natural world for our health. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The Kendida Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet. And Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Omar Sosa: “So All Freddie” from Eggun (OTA Records 2012).]

Birthright

(Photo: Stephen Kellert)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. With all our laptops, smartphones, and televisions, it’s sometimes hard to find time to get outside and enjoy nature. But according to Stephen Kellert, since we evolved with nature, connecting to it is essential for human wellbeing.

Stephen Kellert’s new book, Birthright. (Photo: Jennifer Doerr)

Stephen Kellert is a Professor Emeritus of Social Ecology at Yale University. Along with the eminent biologist E.O. Wilson, Professor Kellert champions the concept of biophilia, the notion that responses to nature are embedded in our genes. So a fear of dogs, and spiders and snakes is innate, as is the comfort of a garden and the wonder we feel at a beautiful sunset. In his new book, “Birthright," Professor Kellert outlines why nature is a must for humans.

KELLERT: Well really it’s fundamentally about our humanity. It’s in our own self-interest and it contributes in so many ways to our health and well-being. Many of our basic tendencies is our ability to reason, our ability to emotionally connect, to avoid things that are harmful to us, and in many other ways we’re deeply contingent on our relationship to the non-human environment.

And we are actually a biological animal, to the extent that we disconnect or separate ourselves from that non-human environment, we do so at the diminishment or impoverishment of our physical and mental health. Increasingly, where we spend most of our time – we spend 90 percent of our time now indoors and 82 percent of us in the United States at least live in an urban area. So, that doesn’t eliminate our need to affiliate with the natural world for our own self-interest, but it certainly makes it much more challenging. And we need to think hard about how we design and develop our built environment, especially our urban environment such that our experience in nature can be an integral part of our everyday lives.

(Photo: Stephen Kellert)

CURWOOD: How important is it that people form a connection to nature in their childhood?

KELLERT: The most important period for learning is childhood, and many of our basic characteristics – whether it be our capacity to emotionally bond with others, to intellectually develop – many of these abilities are nurtured and fostered by our relationship to the non-human environment in many, many ways that we barely recognize.

Even though most children are not specifically taught different kinds of trees and what’s the difference between a robin or a seagull or a duck, or under what conditions does it rain and what conditions does it snow… weather… they nonetheless assimilate these connections that foster and nurture children’s physical and mental development.

CURWOOD: So, what does that mean for someone who was raised with a lot of concrete?

KELLERT: Even if somebody lives in an urban area, they still experience weather, they still see trees, they see grass, they see birds. Then representationally and symbolically through pictures, computers, television, and books. I’m not suggesting that they can’t be improved and children are increasingly disconnected from nature, which is a problem, but nonetheless there are ample opportunities for children in urban areas to experience nature in ways that are deeply meaningful to them in a developmental sense.

CURWOOD: Now, employing the thinking of biophilia and what you say it teaches us, what should we change about our healthcare system?

KELLERT: Well, there is increasing data that demonstrates that the experience of nature can have a therapeutic affect on people. Certainly people who are in healthcare situations, who are ill, have recovered faster, have required less potent painkillers when nature is brought into the heathcare environment, whether it be healing gardens and fountains, pictorial representation and more natural lighting, more natural materials, and so there are ways in which we can incorporate nature in these health care settings. And that has happened in a few healthcare settings, and it’s happening more as the data demonstrate that it actually improves treatment and recovery.

(Photo: Stephen Kellert)

CURWOOD: Biophilia can help save money for healthcare?

KELLERT: It can! I’ll give you a very trivial example… this emergency room was a windowless environment, it had white walls, very sparse furnishings and there was a great deal of aggressive and acting-out behavior between people waiting in the emergency room setting, as well as people waiting there and staff. And they redesigned it at a relatively modest cost, it was still the same windowless environment, but they had a mural of a savannah-like environment, they brought in plants and materials and furnishings and they found a dramatic decrease in aggressive and acting-out behavior, and that this in a sense contributed to the bottom line of that operational facility because of the decline in conflict and stress that occurred in that environment.

CURWOOD: You have a chapter in your book called Aversion- and that prompts me to ask - how is fear a part of biophilia?

KELLERT: Obviously as we evolved for much of our history, we lived as a primate that wasn’t particularly strong or fast, we were quite vulnerable and if we didn’t have an aversion to some things in the natural world, we’d be in trouble. But, even today, you know that continues to be the case, if we lack fear, we get ourselves in trouble such as building in floodplains, or earthquake-prone areas, below sea-level, we’re vulnerable to more hurricanes which is a more recent example.

But fear can also be very positive. Awe is a quality that is defined as fear meeting with reverence, so fear can be an aspect of having respect and appreciation for a power that’s greater than ourselves.

CURWOOD: Perhaps you can tell us about your encounter with wolves.

KELLERT: I will. And, just to set the stage… I wanted the book to be accessible to a broader audience than just scientists and professionals, so I have throughout the book about 20 interludes, which are just stories about myself or about other people which try to bring these abstractions to life. And this was a story I had about an experience with wolves in the wild. I was involved in a research project. I was with Fred Harrington who is a world expert on the wolf howl.

(Photo: Stephen Kellert)

'Fred and I departed close to midnight, driving for perhaps an hour, down old logging roads through dark, thick, and overhanging evergreen forest. We finally arrived at a heavily wooded area where Fred had successfully called wolves before. Fred would periodically play wolf howls then long intervals of silence would follow, as he and I listened intently. Then unexpectedly from what seemed like a long distance away, I heard a sound so faint that initially I thought it was my imagination. Fred’s affirmative nod confirmed that it was a wolf calling in response to the recording. Fred then played the recording more frequently and turned the volume higher. This time the responses became more audible and frequent.

Then a wolf howl suddenly rose without warning from not far away. Then another wolf howled, answered quickly by others. It was clear that the wolves had encircled us, although they remained hidden in the dark woods. The calls were so loud and startling that my reaction was spontaneous and visceral; what had been moments earlier an intellectual engagement had suddenly become deeply anxious, and discomforting. I was at the edge of panic, acutely aware of my total exposure.

I could not see or smell as well as wolves, and the animals produced a strength and predatory prowess that reduced me, at least in my mind to little more than edible meat. I was hardly comforted by reminding myself the wolves rarely, if ever, attack people. We cautiously backed toward the vehicle leaving the equipment. To my immense relief, we finally reached the safety of the truck. I peered back at the lengthening shadows of the new dawn and thought I could see a large wolf. I imagined a fiery glow in his or her eyes – one of curiosity, or perhaps one of hungry disappointment.'

CURWOOD: So, how did this feel?

KELLERT: I was confused by it because on the one hand I was embarrassed by my fear, my terror, of this animal, and on the other hand I realized that something very deep and meaningful had occurred – I had come to appreciate and respect this animal in a way that I had never known before because I experienced it under its own terms, and I recognized its extraordinary power, and prowess, and its magnificence.

Stephen Kellert, Professor Emeritus of Social Ecology and a Senior Research Scholar at the Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

CURWOOD: In your book, Birthright, you write that spiritualism forms a fundamental part of biophilia and human well-being. One person here looking at this said: What hope do atheists have looking at that?

KELLERT: We all have a deep and abiding interest in finding meaning and purpose in our lives. I think that we all want to believe that we’re more than a meaningless speck of dust at a random moment in time. And I think that by having a sense of deep affiliation and connection to the world beyond ourselves in the world gives us a sense of relationship, of feeling of meaningful connection.

CURWOOD: Why did you call your book Birthright?

KELLERT: The notion of Birthright is that we have a right by nature of our birth to affiliate with nature, it’s an inherent tendency. But this is not a hard-wired instinct, this is something that depends upon learning and experience in order to become function. And so it is a birthright that needs to be earned. That was the notion of birthright, it also reflected a beautiful quote, it was written by a fellow named Henry Beston and he wrote: 'Nature is a part of our humanity, and without some awareness and experience of that divine mystery, man ceases to be man. When the Pleiades (which is a constellation) and the wind and the grass are no longer a part of the human spirit, no longer a part of flesh and bone, man becomes, as it were, a cosmic outlaw. Having neither the completeness nor the integrity of the animal, nor the birthright of our true humanity.'

CURWOOD: Stephen Kellert is author of the new book, Birthright, and Professor Emeritus of Social Ecology and Senior Research Scholar at the Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Thank you so much, Professor Keller.

[WOLF CALLS]

KELLERT: Thank you, Steve, I appreciate the opportunity.

Related links:

- More about Birthright

- More about Stephen Kellert

[MUSIC: Paul Winter “Wolf Song” from Common Grounds (A&M Records 1977).]

The Place Where You Live

The prairie of South Dakota (Photo: Bri Weldon)

CURWOOD: This week we revisit "The Place Where You Live" - with another in the Living on Earth/Orion Magazine series. For more than a decade, Orion has called on its readers to put their memories of home on a map and submit essays on its website.

And now, we’re giving those reflections a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe & The Magentic Zeroes “Home” from Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes (Rough Trade Records 2009)]

CURWOOD: Home, home on the range may be the place where the deer and the antelope play - but increasingly it also where people want to live - which can be frustrating to long-time residents.

Writer Linda Hasselstrom on the hillside near her ranch. (Photo: Jerry Ellerman)

Writer Linda Hasselstrom on the hillside near her ranch. (Photo: Jerry Ellerman)

HASSELSTORM: My name is Linda Hasselstorm and I’m from Hermosa, South Dakota. I live on a ranch five miles south of that town and Hermosa is a once very small ranching community that has sprouted large numbers of subdivisions in the past 20 years. Many of the new residents feel that they need to have large so-called security lights that glare in all directions and tend to keep away the wildlife that they have moved out here to enjoy. You can tell the old ranches because they are dark at night.

CURWOOD: Still, the prairie is Linda's home - and at this time of year, she says it deserves special respect.

HASSELSTORM: One of the things about living in South Dakota is that things can change so quickly. We know winter is coming and we prepare for it. And some of us can smell it when it’s about to snow, but it can happen any time. We have to be ready, particularly ranchers because the cattle depend on us. And so, we have to be ready for anything at any time.

Blizzard. Pink sunrise. Snow hisses through the buffalo grass. I can barely see the road a half mile away. The highway patrol advises motorists to stay home. Four SUVs creep away from new houses where cattle and deer grazed a year ago.

The thermometer reads zero. The wind chill factor is thirty degrees below zero. My house moans with each wind gust. Snow ghosts dance on the rims of old drifts.

Twelve whitetail deer lie among the windbreak’s junipers. Porcupines doze in cracks in the limestone cliffs, digesting dried buffaloberries. A great horned owl hugs the trunk of a pine. One set of black horns shows on the southern horizon, telling me eleven pronghorn are gathered there. One head is always up, one set of eyes always watching.

The cattle lie along the dry streambed below the house. Backs to the north, they chew their cud and bat their icy eyelashes.

On this South Dakota winter day, the animals, aware of every shift in the wind, are living comfortable, normal lives. When the moon rises and the wind falls at dark, they will move out of shelter to search for food.

North of here, two trucks have jackknifed and a hundred vehicles skidded and swerved into a mangled mess. Emergency personnel will spend hours untangling the jumble.

The snow piles around tawny grass. Under the sod, roots wait for the moisture that will trickle downward with snowmelt. Only the humans fret and fume against the nature of this weather, against the nature of this place.

CURWOOD: Author Linda Hasselstrom lives in Hermosa, South Dakota. She writes about ranching and the environment and hosts writing retreats. Tell us about “The Place Where You Live.” To find out about the Living on Earth – Orion Magazine series and how to post your essay – go to our website LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Tell us about The Place Where You Live. Directions for posting are on the Orion Magazine website. Some of the essays will be chosen for broadcast on Living on Earth.

- Information on Linda Hasselstrom’s Windbreak House Writing Retreats

[MUSIC: Omar Sosa: “Alejet” from Eggun (OTA Records 2012).]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Annie Sneed, James Curwood, Meghan Miner, and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at just eat organic dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners. The Go Forward Fund and Pax World Mutual and Exchange Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at Pax World dot com. Pax World, for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

Newsletter

Living on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth