April 19, 2013

Air Date: April 19, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Earth Day At 43

View the page for this story

April 22nd 1970 was the very first Earth Day. Denis Hayes, its coordinator, talks with host Steve Curwood about what Earth Day achieved in the early days, and how it might recreate that success today in the face of global challenges like climate change. (07:00)

A Pulitzer for the Climate

View the page for this story

Inside Climate News, a small online non-profit devoted to covering the changing climate, just won the most prestigious prize in journalism. Three Inside Climate reporters took home the National Reporting Pulitzer for coverage of pipeline regulation and the hazards of tar sands oil. Lisa Song, one of the winners, speaks with host Steve Curwood about the honor. ()

Carbon Neutral Capital

View the page for this story

In fall 2012, Copenhagen laid out an ambitious plan to become the world's first carbon neutral capital by 2025. There's still a long way to go, but as reporter Justin Gerdes tells host Steve Curwood, the Danish city has made great progress, with an ocean-water cooling system up and running, a bike super-highway and of course, many windmills. (06:35)

'The World’s Greenest Commercial Building"

/ Ross ReynoldsView the page for this story

Seattle public radio station KUOW reporter Ross Reynolds visits the deep green Bullitt Center along with the man who dreamed it up, Denis Hayes. As Hayes explains, the Center is a self sufficient building designed to emulate a living organism. (09:45)

Goldman Environmental Prize Winners

View the page for this story

The Goldman Environmental Prize is often called the “Green Nobel”. This year’s winners include activists from Italy, Indonesia and Colombia who made a difference in their communities. Host Steve Curwood talks with Azzam Alwash about restoring Iraq's marshes, with South African Jonathan Deal who fought to limit fracking there, and with Chicago's Kimberly Wasserman who helped shut down coal-fired powerplants. (17:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Denis Hayes, Lisa Song, Justin Gerdes, Azzam Alwash, Kimberly Wasserman, Jonathan Deal

Reporter: Ross Reynolds

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

I'm Steve Curwood. Back in 1970 some of the first Earth Day participants were quite serious, but others were rather eccentric and CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite was skeptical. Still, he told America the Earth Day activists had something important to say.

CRONKITE: The gravity of the message of Earth Day still came through. Act or die.

And nowadays Earth Day brings news of the Goldman Environmental Prize winners, including one who's working to help restore Iraq's marshes.

AZZAM: Now, you all have to understand the marsh Arabs are not tree huggers like me or you. They are restoring the marshes because it is a way of life. It's a place where sustainable development has been practiced for thousands of years before we even knew this way of life by those terms.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Earth Day At 43

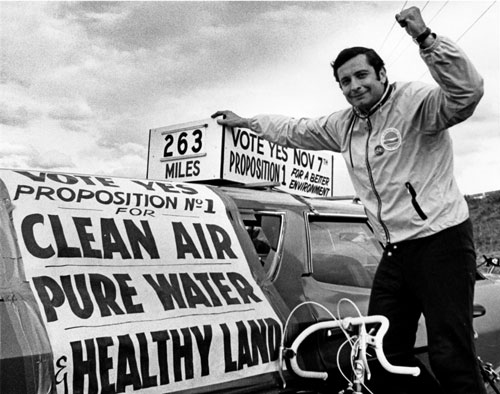

(New York Department of Environmental Conservation)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Earth Day. It began in the style of the Vietnam War protests back in 1970 as a “teach-in” about America’s - and the world’s - badly polluted air and water. And on the CBS Evening News of April 22nd, Walter Cronkite explained its significance.

CRONKITE: Good evening. A unique day in American history is ending. A day set aside for a nationwide outpouring of mankind seeking its own survival. Earth Day. A day dedicated to enlisting all the citizens of a bountiful country in a common cause of saving life from the deadly byproducts of that bounty. The fouled skies, the filthy waters, the littered earth.

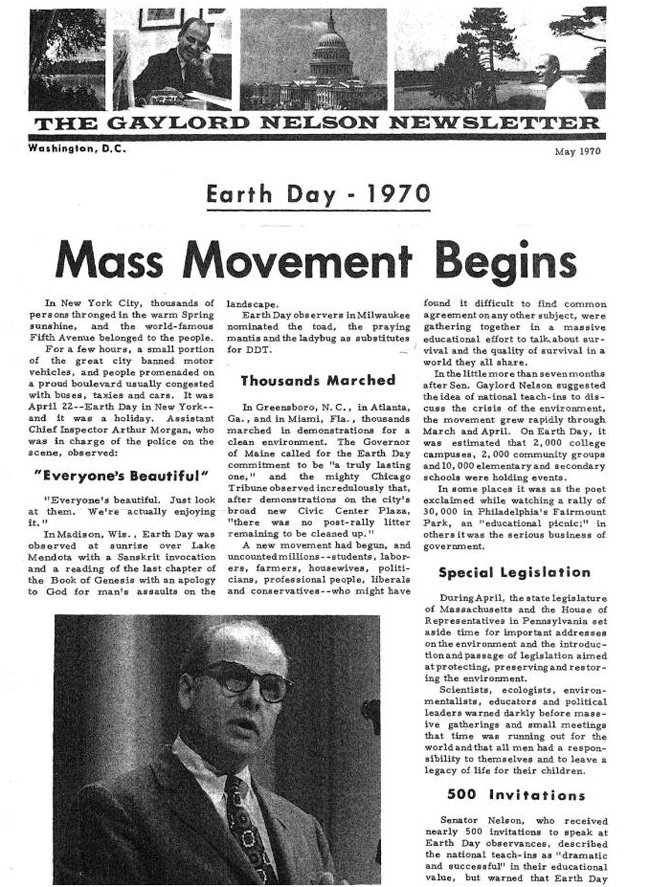

The Gaylord Nelson Newsletter caption read “Earth Day 1970- A Mass Movement Begins.” (NOAA)

CURWOOD: By some estimates, 1 in 10 Americans participated in that first Earth Day. They were mostly young and white. Some were decorous and serious while others were more whimsical and eccentric. Again, Walter Cronkite.

CRONKITE: The gravity of the message of Earth Day still came through. Act or die.

CURWOOD: Denis Hayes, the coordinator of that first Earth Day, gave a call to action at the first rally in Washington, DC.

HAYES: We are systematically destroying our land, our streams, and our seas. We foul our air, deaden our senses and pollute our bodies. That's what America's become. That's what we have to

challenge.

CURWOOD: Well, 43 years later, Denis Hayes is still going strong - and he joins me now from KUOW in Seattle to assess how Earth Day is standing up to being middle-aged. Welcome to Living on Earth, Denis.

HAYES: Steve, it's always a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: So back in 1970, you were worried about air pollution in our environment and our bodies. How did we rise to that challenge? How are we better off today? Or are we worse? the same?

HAYES: Well, we're both. We did a wonderful job with the things that are visible. And there was this period between 1970 and 1974 where we passed the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, Safe Drinking Water Act, Marine Mammal Protection Act, Endangered Species Act, Environmental Education Act and on and on. And where President Nixon felt political pressure, that he succumbed to, to set up the Environmental Protection Agency through an executive order. And all of that stuff took care of those clouds of smoke that were pouring out of our smoke stacks and the really ugly crud that was fouling our rivers. And now we are wrestling with a whole bunch of things that are much more nuanced and sophisticated, many of them things that you can't smell or taste - most of them things that you can't see. But they're every bit as dangerous and now we need to rise to this new set of challenges.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, Earth Day is the world's most widely observed secular holiday with 170 or more countries celebrating. Please give me some examples of how people celebrate Earth Day around the world.

HAYES: It's all over the place. We've had collections of more than 20,000 saffron-robed monks from Southeast Asia coming together for a massive celebration of the Earth in Thailand. We've had things in the most remote villages where Peace Corps volunteers have taken photographs of these things where they're working on environmental projects – sanitation projects and things.

CURWOOD: So, Denis, what is the focus of Earth Day today? In America, one thinks people are planting trees and picking up litter or...do you see Earth Day now as a force to take on the concerns of today such as climate change?

Demonstrators in Washington, D.C. on Earth Day 1970. (Photo: South Coast AQMD)

HAYES: What the power of Earth Day historically has been on those occasions when it really did have some enduring impacts – the most impressive of them I think being 1970 and 1990 – was to articulate a pretty strong set of values, but almost no restrictions upon how people chose to address this. So in the first one we had folks who were pounding apart automobiles with sledgehammers to protest air pollution from automobiles. We had people who were donning gas masks and marching down Fifth Avenue. In 1990, where the theme was in essence, who says you can't save the world, individual behavior is important. You can protest the Exxon Valdez, but Americans who dump their used motor oil down the storm sewer are dumping more than 12 Exxon Valdezes into our most vulnerable waterways every year. Whenever we've tried to do something that is more narrowly tailored, it has diminished in size spectacularly. So I think that its power in the future is going to be one of, once again, creating this framework and then encouraging vast amounts of creativity out in the hinterland as people chose to do what they wish.

CURWOOD: What was the inspiration that led you to become a national coordinator of the first Earth Day?

HAYES: I graduated from Stanford, went off to Harvard, and saw this piece in the New York Times about Senator Gaylord Nelson advocating the creation of a national environmental teach-in. I thought that I might be able to persuade him to let me organize Harvard, or conceivably even Cambridge, or maybe even Boston.

So I, with the arrogance of youth, flew down to Washington, DC and got a 15 minute meeting set up with the senator – and it turned into about a three hour meeting as we discussed what one might do to pull together this event. And I went back with a charter to organize Massachusetts. And two days later, I got a phone call asking me if I'd drop out of college and come and organize the United States. For people at Harvard University, it probably seems like it's not a big step to move from Harvard University to the United States. But for me, it was truly a life-changing experience.

CURWOOD: Later in the show, we're going to walk around with you at the Bullitt Center. That's the building your organization, the Bullitt Foundation, touts as the greenest building in the world today. Can you tell me, what does it look like? What would I know from the outside looking at it that it's a special building?

HAYES: From the outside, probably the dominant characteristics are a huge solar array that sticks out on all sides like a mortar board at a graduation ceremony. Remember, this is a building that in Seattle, where there isn't a lot of sunlight, generates as much energy over the course of the year from sunbeams hitting its roof as it uses. And the second really dominant characteristic are super efficient, very large, self-operable windows that are four feet by ten feet, weigh 700 pounds a piece and provide an internal atmosphere that encourages productivity, general happiness, much greater health, and makes our tenants people who want to remain in the building.

CAPTION (Photo: CREDIT)

CURWOOD: Well, we'll be back to tell more about your building later in the program. Denis Hayes is President of the Bullitt Foundation, and was national coordinator of the first Earth Day, and is chair of the Earth Day Network. Thank you so much, Denis.

HAYES: A pleasure as always, Steve.

Related links:

-

- Earth Day Network

[MUSIC: Van Morrison “Going Down To Monte Carlo” from Born to Sing: No Plan B (Blue Note Records 2012)]

A Pulitzer for the Climate

Tarred great blue heron (photo: Michigan DNR)

CURWOOD: A small online non-profit organization dedicated to covering the changing climate has won the Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, beating out the major newspapers that usually win. Elizabeth McGowan, Lisa Song and David Hasemyer, from Inside Climate News won for their coverage of an oil pipeline that carries tar sands oil from Canada. The Inside Climate team of reporters investigated the 2010 Enbridge pipeline spill in Michigan, which dumped a million gallons of that tar sands oil - also known as diluted bitumen - into the Kalamazoo River. Lisa Song, one of the winners, joins us via Skype. Lisa, we’re all pretty excited here because you were once an intern with us at Living on Earth. Congratulations!

SONG: Thank you. I'm really overwhelmed and honored and just...I haven't processed it yet.

CURWOOD: Now we spoke with you last year about the spill on the Kalamazoo River in Michigan in 2010, and you told us about the diluted bitumen that flowed into the water there. Let's take a listen to what you said then.

Lisa Song was part of the three-person team that won the National Reporting Pulitzer for Inside Climate News. She also used to be an intern at Living on Earth! (photo: Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

SONG: What spilled was not conventional crude oil. It was not the kind of oil that the EPA or the Coast Guard or any cleanup crews had experience with. It was diluted bitumen, which is different, it’s a mix of really thick crude oil called bitumen and these light hydrocarbons. It’s thick, it’s like peanut butter, which is why they have to dilute it. And what happened was the EPA went into the spill thinking it was a conventional crude oil spill. They thought everything was normal, and when this diluted bitumen spilled, it at first floated on the water. So that just reinforced the concept that it was regular crude oil. But over a period of days, the light hydrocarbons started evaporating. And after they evaporated, all you have left is the heavy bitumen, and that’s what sank into the river.

CURWOOD: Now the report that won the world was called the Dilbit Disaster. What role did you play in this?

SONG: I started out mostly reporting on the science of the oil and trying to figure out what actually happened scientifically when this diluted bitumen, or dilbit oil spills into water – what scientists know and don't know about that. Later on I started reporting more on the pipeline regulatory angle, writing about some flaws and gaps in the pipeline federal regulations. And then I also wrote a story about how most of the pipeline oil spills that happen in this country are actually detected by members of the public or people who work for the pipeline company on the ground, and only five percent were detected by the computerized leak detection systems that they have installed on these pipelines.

The burst Enbridge pipeline (photo: National Transportation Safety Board)

CURWOOD: Hmmm. The alarm systems don't work, in other words.

SONG: There are problems with them, and it's very difficult for them to detect leaks remotely.

CURWOOD: So you've changed your pronunciation – diluted bit-chu-men or diluted bye-tumen?

SONG: Um, I think I switch back and forth depending on my mood. There's multiple ways to pronounce it. I tend to use whatever I feel like that day.

CURWOOD: “Dilbit,” huh?

SONG: Yes, that's why “dilbit”; it’s easier to say.

A turtle covered in diluted bitumen, the oil from the pipeline that spilled into the Kalamazoo River in 2010. The Inside Climate Team won the Pulitzer for their coverage of this spill. (photo: Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

CURWOOD: Now the Pulitzer Prize comes at an apt time. Diluted bitumen is the same stuff that spilled when a pipeline burst in Mayflower, Arkansas on March 29. You've been covering this story as well. How are things progressing?

SONG: They're continuing with the cleanup. The company responsible for that spill, Exxon Mobil, they've just excavated the part of the pipeline that burst and they're sending it to a laboratory for metal analysis to try and determine the exact cause of the rupture. And the U.S. Department of Transportation is down there conducting an investigation of this spill. They're continuing to do air quality monitoring in the town. And there are something like 700 cleanup workers on site mopping up the oil.

CURWOOD: Well, they say the diluted bitumen has to go through at such high pressure because of its consistency. And these old pipelines just aren't prepared for it. What have you found?

SONG: Well, the interesting thing is, the age of a pipeline alone doesn't determine whether it's in good shape or not. What really matters is how well a company maintains the pipelines. So there are some brand new pipelines that are out there that are in bad shape because the companies aren't taking the adequate measures to assess the risks, and they're not maintaining it properly. And then there are ones that are really old, but if the company maintains them well, then they are perfectly safe. So I think it's a question of the maintenance of this pipeline and its regulatory history more than the age that will really matter in the end.

CURWOOD: But we don't know that yet.

SONG: We don't know that yet. This is just a general statement of what pipeline experts are saying.

CURWOOD: So, thinking about environmental news coverage, what do you think about the Pulitzer going to an online organization that's devoted to covering climate change?

SONG: Well, I think it shows that climate and environmental issues are really important to the national conversation. Whether it's the Arkansas spill or the Michigan spill, they both happen to be about “dilbit” - that's the same substance that would be going through the Keystone XL Pipeline. And that is a giant national conversation that's been going on for many years. So once the Arkansas spill happened, a lot of people started to connect the dots and Arkansas became more than a story of what happened in Mayflower, it became a part of the national debate about Keystone.

Tarred Painted Turtle (photo: Michigan DNR)

CURWOOD: Lisa Song is a reporter with InsideClimate News, and a recent Pulitzer Prize winner. Thanks again for joining us and congratulations again, Lisa.

SONG: Thank you.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News website

- The report which won the award

- Lisa Song’s profile

[MUSIC: Shuggie Otis “Black Belt Sheriff” from inspiration Information/Wings Of Love (Sony Music 2013)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...Copenhagen is on its way to become climate neutral by 2025. That's just ahead here on Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Next Collective: “Refractions In the Plastic Pulse” from Coverart (Concord Music 2013)]

Carbon Neutral Capital

Nyhavn Canal (photo: Justin Gerdes)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. They call it “wonderful Copenhagen,” and the Danish city has now determined that on a net basis it will stop adding climate changing gases to the atmosphere by 2025. The decision came in an August 2012 city council vote that orders a switch from coal to scrap wood and other sustainable forms of biomass for heat and power. And Copenhagen has also begun to cool its largest buildings using an offshore resource, cold seawater. Back in 2009, Living on Earth's Bruce Gellerman visited the seawater cooling facility as it was being developed with engineer Jan Hoge.

HOGE: So now you are really in the heart of the cooling center. This is inlet for the seawater system. Inside here you have the pipe coming in and then you have these six pumps circulating the seawater into the cooling center and back into the harbor a little bit warmer.

Copenhagen already gets much of its electricity from wind power (photo: Justin Gerdes)

Middelgrunden wind array in Copenhagen harbor (photo: Justin Gerdes)

GELLERMAN: Two pipes, each nearly a yard in diameter, buried 20 feet underground re-circulate water three-quarters of a mile from Copenhagen’s harbor. Originally built to cool off the old power plants' generators, today the system provides cold water to the new district cooling plant.

HOGE: If we didn’t have these pipes we didn’t have this project because it would be so expensive for us to put in new pipes in the ground. And although they’re more than a 100 years old, they look fantastic. We just have to reline them and now we use the seawater from the harbor to cool down our chiller units, and through the so-called free cooling. And what is free cooling? You produce cold water purely from the water in the harbor.

One of the biggest challenges will be getting rid of emissions from privately owned cars (photo: Justin Gerdes)

CURWOOD: That's engineer Jan Hoge with reporter Bruce Gellerman. Well, environmental journalist Justin Gerdes dug into Copenhagen's carbon-cutting campaign during a recent a fellowship from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs International Press Initiative, and wrote it up for Yale’s E360 online magazine. Justin Gerdes reports that the cooling plant is now providing air conditioning at little cost to the environment.

GERDES: They estimate that doing cooling in this way reduces carbon emissions by nearly 70 percent and electricity consumption by around 80 percent compared to conventional air conditioning.

CURWOOD: And the cooling is used largely for?

Jorgen Abildgaard, the City of Copenhagen official charged with implementing the 2025 carbon neutrality plan (photo: Justin Gerdes)

GERDES: For now, it's largely really big buildings, so ones where more people gather. So it's hotels, office buildings, data centers, and right now it's mostly in the city center, but they're going to be expanding the network in future years. But they don't intend to offer it to residential customers. It's actually a very elegant solution in the sense too in that they repurpose the same network of underground tunnels that they use for their district heating system. So this is basically sending chilled water to individual buildings via a network of pipes – so it's not forced air, air conditioning as we would think of it typically used in the United States.

Chillers at the sea-water district cooling plant (photo: Justin Gerdes)

CURWOOD: Of course, when you come into Copenhagen, you see all those wind turbines out there in the harbor. They seem to have a lot of electricity in Denmark. In fact, they might have a surplus. How does this figure into their plan?

GERDES: That is very much in their plans. City officials are basically acknowledging that they won't be able to eliminate carbon emissions entirely within the city boundaries by the timeline, so by the year 2025. And that's largely because of private vehicles. They need more time to convert those vehicles to alternative fuels or electricity. So they're compensating for those emissions by exporting surplus wind from wind turbines located both on and offshore. And they're planning to add 100 new wind turbines over the next dozen years to do that.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about transportation. In reading your article, you say that Copenhagen is going to build a bike superhighway.

GERDES: Yes, of course, most Americans if they have heard anything about Copenhagen, they know it's a bike city. It's one of the world's best bike cities. And they've been remarkably successful - 36 percent of trips in Copenhagen to school or work are made by bike. And for residents in Copenhagen that number is even larger, around half. But they realize they need to do even more to entice residents, and more importantly, people commuting in from the suburbs, to take bikes. And so they're investing money to build up the bike infrastructure. So they're building these so-called bike superhighways. The first of them opened in April of last year, and it connects a suburb north of Copenhagen to the city center. Basically, they're better lit, wide, smooth, bike paths that give these commuters a fast, easy, quick way to the city center and tries to entice them out of their cars.

CURWOOD: How important are efforts by cities to reduce carbon emissions?

GERDES: The effort to slow climate change is really going to be won or lost in cities. Cities are responsible for around two-thirds of both energy consumption and carbon emissions. So if we can follow the example of some of these forward-thinking cities like Copenhagen – ones that are already presenting a visionary way forward and can show best practices – I think other cities, especially ones in developing countries can learn from that example, and we can start putting a downward trajectory on emissions.

CURWOOD: How likely do you think it is that Copenhagen is going to meet this target?

GERDES: I think it is very likely. Right of center politicians in Denmark, in Copenhagen, are not climate change deniers. They support action on climate change. They only disagree perhaps on timelines and how much public money might go toward the effort. So, for example, the carbon neutrality plan that passed in Copenhagen in August of 2012, it did so with support of right-of-center politicians. Similarly last year in March, there was a national energy plan that passed in Denmark that's going to get the county off fossil fuels entirely by 2050. And it passed parliament with the votes of 171 of 179 members at near consensus, which is pretty unthinkable in the context of today's US political climate.

CURWOOD: Justin Gerdes is a freelance environmental journalist. Thank you so much for your time.

GERDES: Thank you so much. Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- E360 article

- Justin Gerdes Forbes Profile

- City of Copenhagen’s Carbon Neutrality page

[MUSIC: Bonobo “Cirrus” from The North Borders (Ninja Tune 2013)]

'The World’s Greenest Commercial Building"

The Bullitt Center solar roof under construction. (Photo: John Stamets)

CURWOOD: Earth Day, April 22, was set as the official opening day of what Mr. Earth day, Denis Hayes, calls the greenest building in the world. It’s a six-story office structure built to house the Bullitt Foundation, which Mr. Hayes heads, and other tenants they hope to attract. As workers were putting the finishing touches on the building, Ross Reynolds of member station KUOW in Seattle got Denis Hayes to take him on a tour.

HAYES: This is a building that functions like an organism - so say it has ears, it has eyes, it doesn't have a sense of smell, but it has pores that open and close automatically depending upon outside conditions. It has a sophisticated nervous system, and it has a brain. It has an alimentary canal, that's the only six-story building in the world with composting toilets. And it functions very much like the Douglas Fir forest functioned when it was here 150 years ago.

REYNOLDS: Let's go inside this building that can see and hear and is like a living being.

HAYES: And I should say that the water on the park...we're not bringing in irrigation water, this will be watered naturally. The water that falls on the building – instead of running off and down a gutter into the street and carrying hydrocarbons into a storm sewer into Puget Sound – the water will be used for all purposes inside the building. The grey water will then be filtered and infiltrated into the rain garden down in front. And again, just like that Douglas Fir forest, the water that falls on the site remains on the site.

The Bullitt Center. (Photo: John Stamets)

So we've done everything we can with the core and the shell of the building, with the tenant improvements we've put in; we've got the most efficient appliances that we can in the kitchens, but in the end, what's left is plug loads - what you as a tenant bring in and plug in as a computer, as a lighting system. And we've limited the budgets; when you come in your lease contains provisions that say this is how much energy you can use per square foot that you've leased. We've got these little kilowatt meters that you measure everything that you're currently using, and it tells you how much of a draw your computers are and your task lights are and your printer is and what have you. And you just calculate a way to stay within that budget.

REYNOLDS: Now a water budget, too, so if I'm overflushing you might be knocking on my door and telling me about it?

HAYES: Well, you'd have to overflush a whole lot, because we have composting toilets that use trivial amounts of water. A flush is about one cup.

REYNOLDS: Denis Hayes is taking some time in his very busy week as they prepare to move into their new building in Seattle to give us a tour and tell us about some of the features.

HAYES: So this will be our big education center, this partnership for urban ecology between the University of Washington and the US Green Building Council and us will operate.

REYNOLDS: And this is a lovely space. It's got floor to ceiling windows. And the ceilings here are really high, full of light, facing south. Great exposure.

The highly efficient windows of the Bullitt Center open automatically when it's hot. (Photo: John Stamets)

HAYES: And by very high we're talking in excess of 20 feet. We'll have all kinds of displays in here and things that will attract the public and we'll bring in school kids. But the real emphasis of this partnership is targeted. If you want to change radically the way things are built, there are a number of decision makers that you need to get engaged. They certainly include architects, but they tend to be wildly enthusiastic about this sort of thing anyway. Developers, a little bit less so. Bankers, deeply skeptical. Appraisers, completely bewildered.

So we're going to be having a series of programs to try to educate all of those about why it is desirable to have features from this building become commonplace. Local politicians and community leaders...I mean two dozen things in this building would have been illegal under Seattle's prescriptive codes. But as long as we can show that this building, by being truly innovative in its integrated design, would have much better performance than the code would have produced, they would give us an exemption and say OK, we'll use your performance standards instead. And we'd love to get that replicated in thousands of cities across the country.

The Bullitt Center under construction. (Photo: John Stamets)

REYNOLDS: I've got to say, I'm impressed with what you're showing me, Denis. But I'm wondering - the cutting edge can be the bleeding edge. Is this Bullitt Foundation building bulletproof or is there technology in here that is a little experimental, that you're not 100 percent sure that is going to work?

HAYES: Ah, no. There's nothing in here that we're not 100 per cent sure that is going to work. That's to say every building gets commissioned. And we've got lots of moving parts – windows that open automatically and close automatically. Shutters that come down automatically, go up automatically. There are things that are going to malfunction in the first month. We've got a first-rate team of building managers who will get them fixed. It will be shaking down but none of these are going to be permanent failures. Everything here exists someplace else. It's just not been put together in one package.

REYNOLDS: And you mention the building sees. That's one way it sees – it sees that it's time to close the shades?

HAYES: Yes. The software on this is relatively sophisticated. The building has a brain. It has a nervous system. So across the street we've got a nerve ending that's a weather station that tells you what's the temperature outside. Is the wind blowing? How fast is it blowing? What direction is it blowing from? Is it raining? And it feeds all of that information along with the internal stuff from the building...how warm is it inside? What is the carbon dioxide level? All that stuff goes down to the building's brain and it decides whether the windows should be open or closed.

REYNOLDS: Well, what else would you like to show us next?

HAYES: To make the tour efficient, why don't we show where the toilets go to? And then we'll show you the toilet itself. Right now we're installing the connections between the toilets on the sixth floor and the compost bins in the basement.

[FOOTSTEPS WALKING DOWN STAIRS]

REYNOLDS: So we're descending into the basement of the Bullitt Foundation's office building here in the final weeks of construction. Denis Hayes is giving us a tour and showing us right now where the poop goes.

HAYES: Each of the bathrooms upstairs has a cell connected through a set of pipes that sort of microflushes on a foam base that comes down here. Inside it will be some compost inserted into it to start the process and some wood chips. And it's just the way poop has been dealt with by nature for millions and millions of years, except that we do it in a somewhat accelerated fashion. There are things you can do with it in an anaerobic condition that is somewhat more sophisticated to produce natural gas, but it also tends to produce stuff that's kind of smelly and what have you. This does not. So we basically decided to turn poop into fertilizer, and the poop will go out and be used as fertilizer.

REYNOLDS: There are grates down here that will open up and is that where the finished fertilizer will come out?

HAYES: That's true. And they will have to be emptied probably once every six months.

Behind that wall of plywood is a 56,000 gallon cistern. The water that comes off of the roof goes back there. And as needed, is pulled out...it's filtered before it goes in, but then it goes into fine-grained filters when it's pulled out. You see those three blue things down at that end, they're increasingly fine. By the time you get to the third filter – the second one filters out things as small as bacteria – the third one filters out things as small as viruses. So you get really pure water coming out of the filters. And then, we put it through – just in case anything snuck past – ultraviolet so we kill any last remnants that are there.

After a year and a half of arguing with various officials, we will chlorinate it, despite the fact that this water is incredibly pure, and pump it throughout the building because there have been cases where some bad stuff has gone in through a faucet and down into the pipes in the form of what they call a biofilm. And even if you have pure water going into a place that's contaminated – it gets contaminated. Whereas if you have chlorinated water, it kills everything that would hurt you as it passes through that. And then we'll have an active charcoal filter on each of the taps so when it comes out we're taking the chlorine back out of the water before you drink it.

REYNOLDS: What delights you most about this building?

HAYES: If you were to say, what is the one thing that we take the greatest pride in, I think if you ask the average person on the street, could you generate enough power on your one-story house to meet your needs in Seattle, they would say, “No, the sun doesn't shine.” We're showing you can generate enough energy on an annual basis to meet the needs of a six-story building in Seattle. And I think that means you've got to be super-efficient in your use of energy. But I think it will be a real revelation to people – the roof of a six-story building is pretty much the same as a one-story building. We've extended ours a little bit, but it's still just a roof. And I think that's really eye- opening.

REYNOLDS: You mentioned you were going to charge market rates. When will you make your nut on your investment in this building?

HAYES: We will be cash flow positive the first year. But the rate of return on our investment in the building, through the first set of leases will be less than if it would be if we put up a standard building and charged people standard rates. And we would have spent 25 percent less on construction costs so we would have gotten appropriately larger returns. Right now, this is an unusual building. There's a large number of people who don't want to come to a building that has composting toilets and an irresistible stairway.

It's sort of self-selecting a bunch of people who do want to ride their bikes to work, and they tend to be the kinds of young people that software firms and communications firms and some engineering firms are trying to attract that are locating here. And over time, I think that...if I were to bet as soon as 20 years from now, this will be the best performing single asset in the Bullitt Foundation portfolio. And I pray that that's true because I persuaded my board to commit one-third of our total endowment to this building. But I feel a lot safer about this investment which we can see and control and walk into and take care of than I do anything we're putting into the stock market or some kind of third world derivatives.

CURWOOD: Earth Day Chairman and Bullitt Foundation President Denis Hayes speaking with Ross Reynolds of KUOW.

Related links:

-

- Bullitt Center

[MUSIC: Jimi Hendrix “Hey Gypsy Boy” from People, hell And Angels (Sony Legacy 2013)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...Earth activism's greatest prize - the Goldman Environmental award - is just ahead. Stay tuned for more at Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Youngbloods: The Dolphin” from Ride The Wind (Warner Bros Records 1971)]

Goldman Environmental Prize Winners

Azzam Alwash of Iraq in the marshes he helped restore. (Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Since 1990, every year around Earth Day the Goldman Environmental Prize winners are announced. There's one prizewinner from each of the six inhabited continents and each receives $150,000. Past winners include Nobel laureate Wangari Maathai, and all the winners are cited for their grassroots activism.

This year’s winners range from Italian zero waste activist Rossini Ercolini to Indonesian forest defender Aleta Baun to Colombian recycler Nohra Padilla. And there are three more we'll speak with in our broadcast, starting with Azzam Alwash of Iraq, who returned to his native land after 25 years in America to fight for the restoration of Mesopotamian marshlands.

ALWASH: The marshes of Southern Iraq are a magical world. They are a wetland, a waterworld, in the middle of a parched, flat desert. My memories of that place are very warm in my heart. It is a place where I went around with my father in a boat as a young boy. To my mind's eye, reeds towered above the boat, covered the sky. The water was clear, the fish darting away from the boats, and every now and then we come to a clearing, and the breeze hits your face and cools you down. You contrast that to the Iraq I came back to 25 years after I left. Death and destruction replaced this verdant place, this Eden. Where there were reeds before, there were now tumbleweeds. Where there was water, there's salt-encrusted desert. Where there was clear blue skies, it became dust-colored yellowish sky.

CURWOOD: And as I understand it, Saddam Hussein drained thousands of square kilometers of these wetlands both to punish the people who lived there and also to make it tougher for rebels who were operating from there. Do I have that right?

Azzam Alwash of Iraq (Goldman Environmental Prize)

ALWASH: Indeed. The marshes of southern Iraq are our Sherwood Forest. For eternity, the marsh Arabs went into the marshes and hid from the Sheriff of Baghdad at any given time. It's a place where the army cannot pursue you, where you know the neighborhood better than anyone else, and where you can live off nature without the need for outside resources. And so in '91, following the liberation of Kuwait, the Iraqi people went into rebellion. Saddam Hussein was afraid the rebels would be used by the west to undermine his regime. And at a time when Iraq was not allowed to sell a single drop of oil, the entire GDP of the nation went into this massive incredible project that ended up in the drying of the marshes, depriving the marshes of their source of life, of the water of the Tigris and the Euphrates.

CURWOOD: This sounds like a massive project that Saddam Hussein did, and, therefore, a massive project to undo. How did you go about restoring these marshlands? And where did the money come from to move all that earth?

ALWASH: Ah, well nature moves water. You see, all you have to do is dig a small ditch, maybe a foot wide, to the water level. And you know what, as soon as the water starts flowing, it starts washing the earth away, and the force of nature widens the breach from a one foot breach to ten feet to 20 feet depending how much water there is. Within six months of water coming back to certain places where conditions are just right, reeds begin growing, and with the water comes fish from upstream, and water buffalo comes back and the people start coming back. Now, you all have to understand the marsh Arabs are not tree huggers like me or you. They are restoring the marshes because it is a way of life. It's a place where they can make a living out of. It's about the economy. It's not about the environment. It's a place where sustainable development and sustainable living has been practiced for thousands of years before we even knew this way of life by those terms.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, there's a proposed dam in Turkey, the Ilisu Dam along the Tigris, that...well...wouldn't it cut the amount of water that these marshlands now get down to a trickle again?

Azzam Alwash of Iraq with a marsh Arab (Goldman Environmental Prize)

ALWASH: Well, commensurate with the drying of the marshes, Turkey began not only building the Ilisu Dam, but a series of huge dams, about 33 major dams that are holding the water of the Tigris and Euphrates away from the marshes. And in fact, these dams have changed the biodiversity of the marshes. The floodwater that comes in the spring as the snows of the mountain of Kurdistan start melting creates these marshes and drives the biodiversity of the marshes. These floods come in just as the reeds are returning from winter hibernation, just as the birds are migrating, just as the fish is spawning. But more importantly, these floods renewed the life of agriculture land and the grasslands around the perimeter around the marshes. And these floods, essentially made agriculture sustainable in Iraq for 7,000, 8,000 years because there's a new layer of silt and clay that gets deposited every year from these floods. And one of the negative impacts of dams is the change of the hydrological cycle of rivers.

So, forevermore, or at least while the dams exist, the biodiversity of the marshes is going to change. We are changing from a flood system to a more brackish system. And I keep on telling the Iraqi officials that I'm not worried about the future of the marshes. Reeds can live in brackish water, rice can't. And if the Iraqi government doesn't do anything to address the issue of flood irrigation not only in Iraq, but in Turkey and Syria then agriculture will die in the land where it was born.

CURWOOD: Azzam Alwash of Iraq. He's one of this year’s winners of the Goldman Environmental Prize. And now we turn to Kimberly Wasserman, who won for her community organizing that led to the shutdown of two coal fired power plants within the city limits of Chicago. Let me start by asking, how did you learn about the health effects of coal plants on people who live near them?

Kimberly Wasserman of Chicago (Goldman Environmental Prize)

WASSERMAN: I heard about it first through the door-to-door organizing I did as a community organizer with the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization. I had just had my first-born son and I was taking him with me to go door-to-door and talk with our neighbors. Over the course of the first couple of weeks we really started to see a lot of families who had children with asthma or adults with asthma or seniors who were being impacted by bronchitis and other respiratory issues. And then about two months into my work, my son had an asthma attack and in taking him to the emergency room and talking with the doctor, we learned that asthma isn't actually inherited, it's based on the environment that you lived in.

So that was really the ammunition for myself to continue to go door-to-door and really try to find out, was there really a sole source for the air quality issues in our neighborhood. And over the course about a year, we came across the coal power plant, a plant that looked very unassuming. It gave off white smoke that a lot of our young people had called “the cloud factory” and when we started to understand what the process for converting coal into electricity was and started to understand there was a lot of contamination coming out of the smoke stacks, we realized we really believed this might be the source of a lot of our problems.

Kimberly Wasserman of Chicago (Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Now, as I gather, your neighborhood, the Little Village, is largely people of Mexican descent with a number of folks who don't have the appropriate paperwork to be in the United States. I imagine they were nervous about all this organizing and attention you were bringing to the neighborhood.

WASSERMAN: Most definitely. As the Mexican mid-west capital, definitely immigration, language and income played a lot into how people participated, but I think our leadership development really hit to that because we wanted our community members to know regardless of language, regardless of immigration status, you have a fundamental right to clean air, clean land, and clean water.

We may not speak English, but we pay our taxes. We pay them every time we buy something in the store. We pay them every time we pay a mortgage on our house. And we are contributing to this society and our community. And really just empowering our community to know that this is about their rights. Reminding our politicians that we don't owe you anything, you owe us. Politicians work for us, we don't work for them. And if we can't change the way their doing things, we'll vote in a person who will.

CURWOOD: Now take me back to a point where you had some researchers come in and document just how deadly these plants were for your community, and what the reaction was to the numbers that they came up with.

WASSERMAN: About two years after we started going door-to-door, the Harvard School of Public Health released a report on the coal power plants in Illinois. When we got our hands on it and we saw, in fact, what we believed was true, that 41 people a year died in our community because of the coal power plants, over 3,000 asthma attacks a year, and over 1,500 emergency room visits a year, that was the ammunition our community needed to go to our politicians and say, “How can you sell our community out for profit? How can you sacrifice us for the sake of industry? Where did we go wrong as a community? Where did we go wrong as a nation?”

And unfortunately the reality was that 41 people dying a year did not move our politicians. They looked at it as, well, for the sake of jobs, we'll keep killing your people in your community. And it really took the education of not just our community, but all the communities in Chicago to understand that the air pollution did not stop at the boundaries of our community. It impacted us all, and we all had to hold these folks accountable.

CURWOOD: Those numbers are astonishing. I mean, if these plants were there for 40 years, and killed about 40 people a year, that's like 1,600 people died.

Kimberly Wasserman of Chicago (Goldman Environmental Prize)

WASSERMAN: Exactly. And actually they were there for about 60 years. So we're looking at about 3,000 people.

CURWOOD: What happened to those power plants? And how has your neighborhood changed as a result of your work?

WASSERMAN: As of leap day of last year, the coal power plant announced that they would be shutting down. And in September of 2012, they did. The air quality has greatly improved. We are right now working on collecting a lot of the data to understand how have the asthma rates locally been impacted? But we do know by looking at other cities – when Atlanta hosted the Olympics, the local emergency rooms actually saw an eight percent drop because the highways were shut down in downtown Atlanta to accommodate the Olympics. And so if you can have an eight percent drop just by shutting down the local highways, we can only imagine what the impact would be by shutting down two of the dirtiest coal power plants in Chicago.

CURWOOD: As part of our Earth Day coverage we are speaking with some of this year’s winners of the Goldman Environmental Prize. That was Kimberly Wasserman of Chicago. And now we go to Jonathan Deal of South Africa. He took on Shell Oil and its plans to frack for gas in South Africa’s wild and scenic dry lands known as the Karoo.

Jonathan Deal of South Africain the Karoo (Goldman Environmental Prize)

DEAL: The Karoo is a rural area, quite sparsely populated. To give people a parallel, in the United States, it looks something like Wyoming. It's a very arid area with a beautiful and rich diversity of succulents. And one of the unique things about it is that everybody that lives in it, wherever they come from and whatever their culture or creed is, has some type of historical connection with the Karoo. Their families either come from there or they've got some memory of the Karoo, and my personal love affair with the environment, it started when I wrote and published a book in 2007 called Timeless Karoo.

Jonathan Deal of South Africa (Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Tell me, what exactly have you been able to accomplish in terms of blocking the fracking in South Africa there?

DEAL: At the very least, even if it were to go ahead, we would have a very stringent set of rules and conditions, and a much more delayed and measured start to the technology than what you have seen in the United States. It has put our government into a position where they could negotiate with a company like Shell to get far more benefits for the country from any sort of revenues if it ever went ahead.

CURWOOD: You have a national moratorium on it at this point.

DEAL: The moratorium was lifted in September the 8th of last year. The Minister of Environment, who is a fairly arrogant lady, almost gave the impression that the licenses for exploration would be issued in a week or two. And here we are in April the next year. I believe it is the result of the number of formal letters we have written to the government promising them that if they issue exploration licenses under these circumstances, we will see them in court.

CURWOOD: Jonathan, what can Americans who oppose fracking in this country learn from your efforts?

DEAL: It's a two-way street. What we can learn together is to harness the power of the media. I want to leave America with the guts of a global coalition starting. And whether I'm busy in a small town in the Northern Cape of South Africa called Williston, or we're talking about an activist busy with the town of Williston in North Dakota, we need to be able to speak to a local representative and say you might think that this issue is local and you're going to getting away with sweeping it under the carpet, but I'm promising you that we're going to take it global.

CURWOOD: Now, something that's true for all of you is getting everyone on board. How hard or how easy was that for each of you? I mean, Kimberly, you had to convince folks who were undocumented to speak up. Assam, you live in a very dangerous part of the world. Of course, Jonathan, Karoo is a vast place with not a lot of people.

DEAL: Steve, it's very difficult to get people to respond to something unless they feel an immediate threat, because essentially you're asking them to sacrifice time or money, resources that are very scarce to a lot of people. Essentially, the way I had to pitch it was to tell them that we're working on the future. This is not for us, it's for future generations of unborn Africans. The effects of what's going to happen is going to come home to roost in future generations.

ALWASH: In the case of the marsh Arabs or Iraq in general, the most difficult task was to convince people that democracy works. That if you actually organize, and make sure your voice reaches decision-makers, change will come. The Iraqis that I met in 2003 had grown up under 50 years of authoritarian regimes where decisions come from the top and everybody executes without question. Then you tell them that ten of you can come up to Baghdad to tell decision-makers about the desires of the community, and the difficulty was, the first time they went, there was no action. The second time they went, there was no action. And to keep on preaching to them that in the end it will work, that was the difficult task. But now, they actually organize trips on their own. It's beautiful. They're learning the skills needed to survive in a democratic Iraq.

CURWOOD: Now it's clear your hard work paid off for all of you, but there must have been times during the process when you wanted to give up. Where were those and how did you get past those low points?

ALWASH: Yes. When your daughter calls you crying because you missed a birthday, when your wife calls you because there's a bill that she didn't know how to deal with. Yes, it's tough. There are times when you question your sanity, and what is it that you're doing. But the job is not done, and you can't leave it midway.

WASSERMAN: I think the hardest part is when you fail. When you try to have something happen, be it an ordinance or law or moratorium, or you try something that doesn't work, you can very easily decide that, “You know what, I have nothing left in me and I have nothing else to give.” But I think the hard part is getting up and wiping yourself off and standing up and saying, “You know what, I'm going to learn whatever lesson it is that I'm supposed to learn from this and I'm going to stand back up again and I'm going to keep moving forward and try to find that mustard to keep moving on. I think knowing that as much as we sacrifice with our families and as much as we sacrifice with our community, that they're looking to us to do the right thing and to keep moving forward.

CURWOOD: You've spent a number of hours, days now, with the other prize winners of the Goldman Environmental Prize. What have you learned from meeting each other?

WASSERMAN: I think I've learned that the answer is right here in front of us. And it comes from every corner of the world. The reality is that our solutions are in our voice and in our communities and we just need to keep fighting them forward.

DEAL: I've learned that there are battles around the world that many of us are not even aware of. I've met three women – the prize recipients – Kimberly, Nohra and Aleta – and the two ladies – one from Indonesia and the other one from Colombia are absolutely the bravest women I have ever met.

ALWASH: Here, here.

DEAL: For me to stand up against a giant like Shell in a well functioning democracy like South Africa is one thing. For them to take on corporate and government interests in countries like Colombia and Indonesia takes real guts.

ALWASH: I'm looking at every one of us. And my conclusion is that we're all stubborn. We do not give up. And that's what it takes I think.

CURWOOD: Azzam Alwash is an Iraqi. Jonathan Deal's a South African. Kimberly Wasserman is from the south side of Chicago. They are three of this year's six Goldman Environmental Prize winners. Thanks to all of you.

GUESTS: Thank you.

Related links:

-

-

-

- Goldman Environmental Prize

[MUSIC: Shuggie Otis “XL-30” from Inspiration Information/Wings Of Love (Sony Music 2013)]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth, what's possible if only we could store renewable energy.

BERLINGUETTE: My utopian view here is for every home in suburban America and Canada not to be connected to the grid in any way.

CURWOOD: A new way to make that dream come true...that's next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Alicia Juang, Qainat Khan, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Dana Chisholm and Noel Flatt helped with engineering this week. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. A special thanks this week to KUOW, Seattle. You can find us anytime at LOE.org. And check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield, working to produce healthy food for a healthy planet. Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from you our listeners, The Go Forward Fund and the Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth