May 10, 2013

Air Date: May 10, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

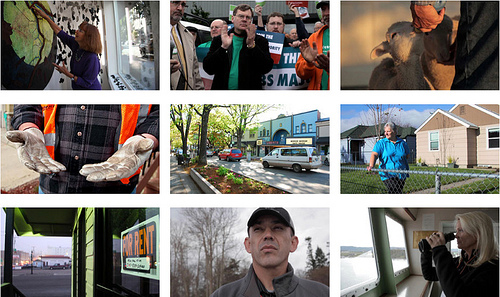

Saving Money with Environmental Regulation

View the page for this story

Critics argue that EPA regulation is costly to business and the US economy. But a new report from OMB shows that the financial benefits of environmental regulation outweigh the costs ten-fold. Harvard Professor Joe Aldy talks with host Steve Curwood about benefits of EPA rules (06:00)

Another Coal Port Bites The Dust

View the page for this story

Three of the six proposed port facilities designed to ship coal to Asia from the Pacific Northwest have been abandoned. Ashley Ahearn of the public broadcasting collaborative EarthFix talks with host Steve Curwood about the energy company Kinder Morgan’s decision to scrap its plans to build at the Port of St. Helen’s. Also, the thoughts of LJ Turner, a rancher in coal country from EarthFix's Voices of Coal Project. (07:05)

Environmental Organizations Under Pressure to Divest Fossil Fuel Investments

View the page for this story

In response to a national movement, colleges and cities around the country are moving their endowments out of fossil fuel stocks. But Dan Apfel, executive director of the Responsible Endowments Coalition tells host Steve Curwood that some big environmental organizations have yet to follow suit. (05:30)

Shale to Solar

/ Margaret KraussView the page for this story

Supporters of natural gas say it can serve as a bridge fuel to help us transition from dirty energy sources like coal to renewable power. Now some Pennsylvania farmers who allowed gas companies to drill on their land are using the lease payments to purchase solar panels. (04:30)

Painted Turtles and Climate Change

View the page for this story

Climate change is impacting various animal species around the world, but Painted turtles may face a particularly strange and formidable challenge. Steve Curwood talks turtles with Iowa State biologist Rory Telemeco. (06:35)

Alligators All Around

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Alligators are cold-blooded, but as Mark Seth Lender observed on a trip to the St. Augustine Alligator Farm and Zoological Park in Florida, they can get pretty hot, come springtime. (02:30)

Romance and Spring Harvest At Paradise Lot

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

For most gardeners, springtime means a time to sow. But for perennial gardeners spring is a time to reap. In their new book, Paradise Lot, gardeners Eric Toensmeier and Jonathan Bates tell their personal stories of finding romance and growing a food forest of perennial plants on a degraded backyard plot. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb took a trip to Holyoke, MA to see and sample their spring harvest. (12:35)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Joe Aldy, Dan Apfel, Mark Seth Lender

Reporters: Ashley Ahearn, Margaret Krauss, Bobby Bascomb

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Another proposed terminal to export coal to Asia bites the dust.The fight to build these Pacific Northwest ports pits activists against would-be rail and dock-workers - and the stakes are high.

AHEARN: This would raise US coal exports by half, again, if just one of these terminals was built. So we're not talking just about a coal skirmish in the Northwest, we're talking about questions about our national energy policy playing out right here in the Northwest.

CURWOOD: Meanwhile in shale country, some farmers with gas leases are using the cash to put solar panels on their property.

MORINVILLE: Those who have disclosed to us, I would say 70 to 80 percent have disclosed that some form of shale money went towards the purchase of the solar equipment.

CURWOOD: We'll have those stories, and some alligator love, and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

Saving Money with Environmental Regulation

Joe Aldy (photo: Harvard Kennedy School)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, This is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

On May 9th, Gina McCarthy’s nomination to head the Environmental Protection Agency was stalled in the Senate’s Environment and Public Works Committee by a GOP boycott. And while Ms. McCarthy is likely to win full Senate confirmation eventually, the EPA itself is under attack from Republicans who say the agency imposes far too many costly regulations.

So the White House is fighting back. The latest annual review from the Office of Management and Budget shows that the benefits of EPA rules far exceed their costs. Joining us is economist Joe Aldy. He's a former Obama White House staffer who now teaches at the Kennedy School at Harvard. Welcome to Living On Earth.

ALDY: Thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, Joe, first off, what is the Office of Management and Budget?

ALDY: The Office of Management and Budget is responsible for coordinating the review of regulatory policy for the administration. So they are tasked, and they’ve been tasked dating back to the Reagan administration, to work with the regulatory agencies as they develop, propose and eventually finalize regulations, and especially the major regulations - the ones that have significant economic benefits and/or cost to the US economy.

CURWOOD: Now, what’s this report that OMB puts out?

ALDY: So in their role as the coordinator of regulatory policy they conduct this annual review that they submit to Congress. As they found in their assessment of the regulatory program across the government, EPA has a significant role in regulatory policy. They have the largest share of benefits and cost in terms of the federal regulatory program, and importantly, they found that the estimated benefits are significantly larger than the estimated cost of the regulatory actions both in the past year as well as over the past 10 years of the regulatory action.

CURWOOD: Give me some of the numbers here, Joe.

ALDY: Right. So if we look back in 2012, the federal government had benefits from the regulatory program in the order of about $50 to $115 billion, and 60 to 80 percent of those benefits were from EPA regulations. And the vast majority those benefits are actually from reducing premature mortality from air pollution. The costs in the federal program last year where about $15 to $20 billion. EPA was about half of those costs. So they impose a cost on the economy but their delivering by about a factor of 10 additional benefits to the United States in terms of reducing air pollution and the associated mortality impacts from it.

CURWOOD: So, wait a sec. We’re talking about a half a trillion dollars worth of benefits from air pollution?

ALDY: If we’re looking at it over time, over the past 10 years, you're looking at something along the order of half a trillion dollars worth of benefits.

CURWOOD: Joe Aldy, why then is there so much criticism that the EPA is costing the economy?

ALDY: Well, they do impose real cost. There are costs from their actions. Those costs tend to be concentrated in specific industries. They then express concerns about costs they have to bear. The utility air toxics rule that EPA has promulgated will deliver real costs on the utility sector. There are a lot of really old coal-fired power plants that have never done anything to the control emissions of mercury and other air pollutants. They all actually have to incur significant different cost to install scrubber technology to clean up the pollution - or they’ll have to shut down. So there are real costs there.

I think that people who raise concerns about these costs, put so much more weight on those costs and very little weight on the fact that especially the elderly, children and those with bad respiratory and cardiovascular health will benefit from having longer healthier lives as a result of that regulation. So I really think it has to do at the end of the day with the concentration of the costs born by industry and how they express their concerns through the political process.

CURWOOD: So what you’re saying is that the costs, more often than not, show up on the corporate balance sheet; the benefits, more often than not, show up with individuals feeling better.

ALDY: It’s the difference between the balance sheet for a corporation, and the health of families around the country. I mean, that fundamentally is the difference between the benefits and the cost of many of the EPA’s regulations.

CURWOOD: So how does this report impact the debate over the EPA’s role?

ALDY: Well, I think it’s important to illustrate again, and we’ve seen this over the course of a number of these reports that have been issued in the past decade, that EPA’s been promulgating regulations that make us as a society better off, that deliver public health benefits - when we monetized these public health benefits - that are significantly greater than the cost we as a society bear to deliver those benefits. And that’s the whole point of government regulation. What I teach at the Kennedy school, the government should intervene in the economy and implement new regulations if they can identify a market failure - certainly pollution is a sign that the market is not working - and do so in a way that increases the net benefits to society. And that’s what this OMB report has found again, and I hope it helps to inform the debate about what constitutes thoughtful, prudent, regulatory policy in this country.

CURWOOD: I want to also ask you about Gina McCarthy? She’s the new nominee to head the EPA. If confirmed, how do you think this debate over the financial costs and benefits of regulation are going to shape her ability to do her job?

ALDY: Well, I think the important thing is, in my experience, Gina McCarthy is very pragmatic. She draws from incredible experience working at the state level, but also at EPA. In fact, if you look at the economic benefits and cost of EPA regulations that were reviewed by OMB, the vast majority of them are regulations she ushered through the process in her position as head of the air office of EPA. So I think this will continue to play an important role for her as administrator, assuming she’s confirmed, and I think her track record over the past four years demonstrates how she works on regulations to make sure they deliver the biggest bang for the buck for the American people.

CURWOOD: Joe Aldy is Faculty Chair of the Regulatory Policy Program at the Kennedy School at Harvard. Thank you so much, Joe.

ALDY: Steve, thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Joe Aldy’s faculty page at Harvard

- Read the OMB report

Another Coal Port Bites The Dust

Coal mine facilities in the Powder River Basin, Wyoming (photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: As coal use declines in the US, many coal companies are looking to export. But to get the abundant coal from Montana and Wyoming to Asia, the companies need new deep water terminals in the Pacific Northwest. And that's proving to be problematic. At first, six different terminal sites were under consideration, but that number keeps declining, and another has just dropped out. Ashley Ahearn of the public broadcasting collaborative EarthFix has been following this issue, and joins us from Seattle. Hi there, Ashley.

AHEARN: Hi, Steve.

CURWOOD: So what’s the latest?

AHEARN: The latest is that one of the four remaining export coal terminals proposed for Washington and Oregon has dropped out. This is coal that’s being moved from the Powder River basin of Wyoming and Montana, and the coal companies, as US consumption drops, are looking to get that coal to Asia. So they’re trying to get it through the Northwest by train and loading it onto terminals. This terminal, Port Westward, was located on the Columbia River, and it was the third largest of the coal terminals still on the table at 30 million tons per year.

CURWOOD: So what happened? Why did Kinder Morgan, the company that proposed building that terminal, decide to walk away from the project?

AHEARN: Well, Kinder Morgan looked at the site for a couple of years, and decided it wasn’t going to fit the parameters for the terminal they wanted to build. And another interesting thing to note here though is that Portland Gas and Electric operates natural gas power plants here, and they had raised some strong opposition with concerns about coal dust that would have come off the terminal if it were built near their facility. So there’s also local environmental opposition, alongside a very real business interest. That means a lot to the port of St. Helen’s where this terminal would have been built. When they voiced opposition, that was potentially a nail in the coffin for this proposed coal terminal. I talked to Allan Fore, the spokesperson for Kinder Morgan, about whether or not this was about coal, as a commodity in particular.

FORE: Certainly, there’s no question that there’s strong feelings about the commodity. Anytime you’re looking at siting a facility, an energy facility, a storage facility, increasing train traffic, increasing water traffic, all part of the infrastructure system to the country, there are those who aren’t going to be happy about it, and it’s part of doing business.

AHEARN: That was Allan Fore, a spokesperson for Kinder Morgan. I talked to him this week.

CURWOOD: Now, I understand that Portland Gas and Electric was concerned about that location, but what about the environmental protests that have been pretty intense out there. The governors of the states of Washington and Oregon have raised environmental questions as well.

AHEARN: You’re right, Steve. There is very strong groundswell of environmental opposition. A lot of folks out here are very concerned about increases in coal train traffic, potential coal dust escaping from the coal trains and safety issues. But there’s also right alongside very strong support. Unions are excited about the opportunity for construction jobs, the rail jobs, the terminal jobs that will come from building these facilities in the Northwest, while environmentalists say there’s not a lot of benefit to people that live in Washington state or Oregon because the coal trains will come through. It’s not our coal that’s being mined - it’s coal that’s mined in Wyoming so the royalties go to that state and we get the pass-through costs. And, Steve, there have been surveys done about public opinion around coal exports. 50 percent, according to a recent poll, support coal exports, 32 percent strongly oppose, so it’s very much a landscape that’s shifting, but by no means do the environmentalists own the field out here.

A coal train travels along Puget Sound en route to an existing coal export terminal near Vancouver, B.C. There are still three coal export terminals under consideration in Washington and Oregon to move coal from the Powder River Basin to Asia. (photo: Katie Campbell/EarthFix)

CURWOOD: And, of course, some of the environmental activists say this contributes to climate change, and we shouldn’t built anything that would help burn more coal.

AHEARN: And that is the huge elephant in the room, of course, global climate change. And coal is the single largest contributor to global CO2 emissions.

CURWOOD: So there were originally, what, six coal export terminals on the table proposed for the Pacific Northwest - now half of them are gone. What do you think is going on here?

AHEARN: Well, I think as coal companies really look through the permitting process and what goes into getting a coal terminal built here, they’re realizing this is about bang for buck. So you want to be moving as much coal as you possibly can through a facility that you’re going to be spending millions of dollars to permit. So we’re seeing the smaller ones drop out. These are the 8 million, 10 million ton per year terminals that were proposed in Washington and Oregon. Those are off the table, and the field is narrowing. There is still one small terminal proposed also for the Columbia River, but the big ones are in Washington now at Longview and near Bellingham, Washington. And these are the 48, 54 million tons of coal per year. To give you some idea, some perspective here, Steve, we export about 100, 125 million tons of coal per year. So this would raise US coal exports by half again, if just one of these terminals were built north of Seattle. So we’re not just talking about a coal skirmish in the Northwest - we're talking about questions about our national energy policy playing out right here in the Northwest.

Ashley Ahearn covers science and the environment for KUOW and EarthFix, a multimedia reporting project based in the Northwest. (photo: EarthFix)

CURWOOD: Still, the numbers have been dropping. So what do you see for the remaining proposed terminals? What are people saying?

AHEARN: Well, I think it’s still anybody’s guess at this point. The smaller terminal proposed on the Columbia River is going through the permitting process. As with the other two, they’re just starting the scoping process to see what are the environmental and potential health impacts that should be accessed in the review of these projects. So it’s early on. We’re going to be watching this for a couple of years. My hunch, though, is that the field is going to continue to narrow. We might get one of these massive terminals built. I don’t know that we’ll have all three.

CURWOOD: That’s Ashley Ahearn of EarthFix. Thank you so much, Ashley.

AHEARN: You’re welcome, Steve.

CURWOOD: As well as reporting on this issue, EarthFix has been listening in to local people who both favor and oppose the export of Powder River Basin Coal. We've been broadcasting some of those Voices of Coal. Here's another.

EarthFix's "Voices of Coal" project brings together diverse perspectives on the coal export debate in the Northwest. (photo: EarthFix)

TURNER: I'm LJ Turner. I’m a rancher here in the Powder River Basin of northeast Wyoming. We’ve lost about 6,000 acres just as a pure roll of the dice. Our leases were all over in the area where the coal mining is. It was a beautiful place to run cattle. It was some of the nicest country in the world. I miss it.

[COW MOOS]

TURNER: I hate to say it, but where the land is being coal mined it’s being destroyed. The spring holes and all of the water along the creek are fueled by these aquifers that run along the creek bed and where the coal mine down there has just completely mined across the creek doesn’t exist anymore. And so it’s gone. A lot of my friends and neighbors in this area do not believe in climate change at all, and I can’t see why people don’t. The first winter that dad was here in 1919, he said it never got above 20 below for six weeks. This last winter we had green grass in February.

[SHEEP BAAS]

TURNER: And it’s changing. It really is. I'm scared of it. I'm just scared of it.

CURWOOD: Rancher LJ Turner from the Voices of Coal project from EarthFix. There’s a link on our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Check out Earthfix’s original report

- The “Voices of Coal” project website

- Previous Living on Earth story about the coal port facilities

- Check out other perspectives from the Voices of Coal Project on LOE

[MUSIC: Andrew Bird “Near Death Experience Experience” from Break It Yourself (Mom + Pop Records 2012)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...Fighting climate change while cashing in on fossil fuel. Green group endowments come under fire from the divestment movement. That's just ahead on Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Tin Men: “Livin And Lovin On The Westbank” from Avocado Woo Woo (Tin Men Music 2013)]

Environmental Organizations Under Pressure to Divest Fossil Fuel Investments

Harvard student demonstrating for divestment from fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The movement to divest from fossil fuels is catching fire. Four universities and 10 US cities, including Seattle and San Francisco, have announced plans to divest their holdings in corporations that profit from the extraction of global warming fuels, especially oil and coal. But it appears most big environmental organizations have yet to follow suit. Groups including The Nature Conservancy, the World Wildlife Fund, and Conservation International invest part of their endowments in the very fossil fuel industries that are linked to climate change. Dan Apfel is Executive Director of the Responsible Endowments Coalition and joins us from New York. Dan Apfel, welcome to Living on Earth.

APFEL: Thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: It might come as a big surprise that some of the environmental organizations are investing in the fossil fuel industry. Can you explain how exactly does this process work?

APFEL: Well an organization like The Nature Conservancy, which has a little over a billion dollars, has an endowment and other investments that it raises from donations over time and from the growth of their investments. They typically work with an investment advisor or consultant to help them pick investments that are generally in the stock market and also in private equities which are privately held companies. And they try and make returns in order that they have more money to implement their mission in the future.

CURWOOD: How much money are we talking about here?

The World Wildlife Fund seeks to protect and preserve the world’s biodiversity, but had yet to respond to Living on Earth’s inquiries about fossil fuel divestment at the time our program was recorded. (photo: World Wildlife Fund)

APFEL: It adds up to be maybe $10 billion total.Colleges and universities have about $400 billion, and US pension funds have on the order of something like $10 trillion.

CURWOOD: How much is invested by green groups in fossil fuels?

APFEL: I don’t have an exact number, but fossil fuel stocks make up about 13 percent of the US and global equity market stock market. So probably around there, 13, 14, 15 percent of their holdings.

(photo: Conservation International.)

Conservation International had yet to respond to Living on Earth’s inquiries about fossil

fuel divestment at the time our program was recorded.

CURWOOD: Now there are some groups like The Nature Conservancy who openly accept funds from companies like BP, Chevron, and Exxon. So is investing in those same companies a different issue in your mind?

APFEL: You know, it is a little bit different because they’re taking money that has been made in the past. Investing in these companies is actually betting these companies are going to succeed in the future. All investors want their investments to perform well, but for these investments to perform well, that really means that more fossil fuels need to get burned, and that’s really inimical to the mission of the environmental organization.

CURWOOD: Now, in all likelihood, a typical person listening to this, if they have investments in a mutual fund, is, well, probably investing in fossil fuels and might not even be aware of it. How possible is it that these green groups don’t really know where their investment dollar is going?

APFEL: Organizations with large endowments, with millions of dollars, typically have an understanding of where their investment dollars are. And we really believe that once you know you have the obligation to do something - and I think most of these organizations already knew, but if they didn’t know before this divestment campaign, they definitely know now.

The Nature Conservancy was not able to provide a response by the time Living on Earth went to air. (photo: The Nature Conservancy.)

CURWOOD: So, now that they are aware, what can these organizations, or for that matter the average person for that matter, do to divest from the fossil fuel industry?

APFEL: Yes. So the first thing that anyone needs to do is, like you said, find out. I think for an individual, it’s really important to look and see what investments you have. So you want to go out and find managers that don’t invest in fossil fuels and ideally are investing in the future. So, really are investing in the solutions to climate change, to mitigate climate change. We’re actually encouraging colleges and universities to invest five percent of their endowments in solutions to climate change.

CURWOOD: What are the core arguments that endowments should divest from fossil fuels, in your view?

APFEL: There’s a few different arguments for endowments to divest from fossil fuels - and I would also say invest in climate solutions. The first is that it’s really the most powerful statement an investor can make with their money. But there’s also a financial angle. Fossil fuel companies are valued based on the amount of proven reserves they have on the ground. But we can’t actually afford to burn those reserves, because if we do, we know for a fact that the global temperature will rise more than two degrees, and that they can actually only burn 20 percent of those reserves. Either we’re going to burn those reserves and global temperatures are going to rise way more than two degrees, or we’re going to have to keep them in the ground, and that means that fossil fuel companies are overvalued.

The Sierra Club says it has divested from its fossil fuel interests and the Sierra Club Foundation is in the process of doing the same. (photo: Sierra Club.)

CURWOOD: So in other words, you’re saying, divesting in fossil fuels, in your perspective, is not only the right thing to do to help protect the planet, but also the right thing to do to protect the portfolio, which you forecast will be devalued by the regulation of carbon in the years going ahead.

APFEL: Exactly. You know what...the fossil fuel companies have to have their values decline. Therefore, their value in our portfolio has to decline if we have any chance at keeping global warming below the two degree temperature rise. It’s also an important reason for investing in climate solutions. Those are the companies that are going to be profitable if we’re making a transition to a low carbon economy.

Natural Resources Defense Council is a grassroots environmental activism group that does note directly invest in extractiveindustries, but is still reviewing its portfolio regarding any indirect fossil fuel investments, such as ETFs, index funds and private equity limited partnerships. (photo: Natural Resources Defense Council.)

CURWOOD: And I guess your view is if we don’t make the transition, everything else is academic?

APFEL: Yes. You know, what I say is if we can’t invest in our future, we really shouldn’t be investing at all.

CURWOOD: Dan Apfel is Executive Director of the Responsible Endowments Coalition. Thanks so much for taking this time with me today, Dan.

APFEL: My pleasure. Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: We contacted The Nature Conservancy, the World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International, The Sierra Club and NRDC for comment. The Sierra Club says it is divesting, and NRDC says it's reviewing all its holdings. The Nature Conservancy said they had nobody available to comment. And as we go to air, we've not heard from WWF or Conservation International.

Related links:

- The Nation: Time for Big Green to Go Fossil Free

- Responsible Endowments Coalition website

[MUSIC: Groove Collective “Melbourne Dub” from Live And Hard To Find (2013)]

Shale to Solar

Sunset at Shared Acres, land Dwayne Bauknight feels conflicted over leasing for fracking. (Photo: Margaret J. Krauss)

CURWOOD: Supporters of hydraulic fracturing - or fracking - say the increasing availability of natural gas gives the US a way to replace coal and oil and provides a bridge fuel to renewable energy sources, and a cleaner energy future. In Marcellus shale country, some farmers with gas leases are using this bridge fuel to get right into solar. From the Allegheny Front, Margaret Krauss has the story.

KRAUSS: Dwayne Bauknight drives me onto his Washington County property in a golf cart. He pulls a U-turn to park between two rows of 15-foot tall solar panels and shows me how they work.

BAUKNIGHT: When it’s producing it’ll go through all those inverters, all those yellow things,

and then come out of that straight meter right there.

Dwayne Bauknight says he installed solar arrays on his farm to do something good for the environment. (Photo: Margaret J. Krauss)

KRAUSS: Bauknight and his family signed a gas lease with Range Resources in October and used the money to install a 38.4 kilowatt solar array on their farm, Shared Acres. Seven years ago Bauknight decided to leave a job as a financial advisor and become a farmer. He says his two careers aren’t so different - now he grows food instead of money. He does a lot of the same kind of decision-making, he said, using the same math, analyzing risk. Bauknight is conflicted about drilling for environmental reasons. But for his family’s sake, weighing the risks, he couldn’t not take the money. So if he was going to lease, he figured he could use the gas money to do something good for the environment.

BAUKNIGHT: There’s different ways to sustainability, and one of the ways to sustainability is to take our fossil fuels and invest them in renewable energy. I think that’s what we’ve been lacking for a long, long time.

KRAUSS: In looking to the future, Bauknight had a new risk to factor in. The golf cart helps Bauknight get around the property because he’s still having trouble walking. Last summer, while trying to remove a tree from the property with a backhoe, it fell - on him, leaving him with a plate and eight screws in his lower back. Driving back toward his house in the golf cart, I asked Bauknight what he thinks about when he looks out at the solar panels.

BAUKNIGHT: I don’t know. Satisfaction.

KRAUSS: Just two miles down the road is another Duane. Duane Miller’s family has been farming this land for five generations. Miller has no qualms about drilling for shale gas. He sees it as a boon for farmers like him who were just getting by.

MILLER: If someone offered to give you a bunch of money, what would it mean to you? [LAUGHS] I got out of debt. I hadn’t been out of debt since I was 18 when I started farming, when I took over from my dad.

Duane Miller in front of the solar array he installed to reduce and stabilize his energy bills. (Photo: Margaret J. Krauss)

KRAUSS: Miller’s no environmentalist. He installed solar panels so he’d be free of energy bills. It also let him quit milking cows and raise beef cattle instead. It’s a lot less work, and he can still afford to farm. What farmers like these two Duanes choose to do with their gas money has been a question for Tim Kelsey, an agricultural economist at Penn State University. He’s not surprised some are taking gas money and investing it in solar.

KELSEY: The nature of farming involves kind of long-term investments.

KRAUSS: The state doesn’t keep track of how many farmers have used gas money to buy solar panels. But Joe Morinville, who owns Energy Independent Solutions, a solar company near Pittsburgh, has done some research of his own. He estimates that 25 percent of his customers are farmers and that of those number, many have turned to solar thanks to gas.

MORINVILLE: Those who have disclosed to us, I would say 70 to 80 percent have disclosed that some form of shale money went towards the purchase of the solar equipment.

KRAUSS: Solar arrays can come with a six-figure price tag. So while investing in solar might be out of reach for a typical farmer, shale money makes it possible. Back to Dwayne and Duane. Duane Miller says solar panels are a lot like a gas well. Both are domestic energy sources right there on his land.

MILLER: There’s an awful lot of energy that we’re not using in this country that’s here. It’s just a matter of harnessing it, getting the technology to use it. It’s not free energy, but it comes close.

KRAUSS: Dwayne Bauknight isn’t sure he’d sign another lease. He thinks we’re effectively roasting the planet with our use of fossil fuels like natural gas, and that drilling has to stop. So for now, he contents himself with building the bridge between fossil fuels and renewable energies, doing what he thinks is best.

BAUKNIGHT: Everybody's got to make up their own private decision. It’s between you and your farm.

KRAUSS: I’m Margaret Krauss.

CURWOOD: Margaret’s story comes to us from the Pennsylvania radio program, The Allegheny Front.

Related link:

Check out the Allegheny Front, an environmental radio program based out of Pennsylvania

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell “Disfarmer Theme” from Disfarmer (Nonesuch Records 2009)]

Painted Turtles and Climate Change

Baby painted turtles heading back to the water (photo: Rory Telemeco)

CURWOOD: Now, climate disruption affects different species in a variety of ways. And scientists at the Iowa State University have discovered that Painted turtles may be facing one of strangest threats of all; in places the population is at risk of becoming all female. Rory Telemeco is a biologist at Iowa State University. He says it has to do with how the sex of turtles is determined.

More baby painted turtles (photo: Rory Telemeco)

TELEMECO: Painted turtles, along with many other reptiles, and some fishes and a few other things, have a different form of sex determination than what we generally think of in mammals. Mammals have their genotypes, their chromosomes determine whether they are male or female. We have XYs produce males, XX produces females. However in many of these reptiles, such as these turtles, the temperature during development, during a fairly short window of about a month, during the middle third of development, determines whether or not the offspring will be male or female. Cool nests producing males and warm nests producing females.

CURWOOD: So what you’re saying is that warmer temperatures produce more females.

TELEMECO: Potentially, though there are a number of ways that turtles could potentially buffer themselves from changing climate. We know these turtles have been around for a very long time. As a group, turtles have been on earth for 200 million years. The earth's changed a lot over that period. So they have some potential to respond to environmental changes. The question is, what avenues might work, and what avenues might not.

CURWOOD: So what did you do to determine the impact that climate change could have on the Painted turtles sex ratio?

TELEMECO: Well, the primary thing we were trying to get at was we wanted to know, will nesting earlier in the year be a mechanism that could buffer these populations from climate change? We know that shifts in the onset of reproductive events, really any major event in the life of an animal - these are called phenological changes - are changing really really rapidly. That's what we typically see when we go out to try to measure how is climate change affecting organisms. We see flowers blooming earlier. We see leaves bursting earlier on trees. Birds and butterflies are migrating earlier. Frogs are singing earlier, and things like turtles and lizards are nesting earlier in the year. It’s a really common response. And this leads to the question, are these organisms buffering themselves from climate change by nesting and doing their things earlier in the year when it’s a little cooler. We really wanted to know whether or not that was going to work. And so, we looked at these turtles, we have 25 years of research on a single population of Painted turtles in the Mississippi River. We took all that information. We put it into a mathematical model, and what we actually found is that nesting earlier in the year by itself does very little good. If it’s the only thing that the turtles have at their disposal, have you, to sort of protect themselves from climate change. It would only buffer them to about a degree increase in temperature. Any more than that, it would have no buffering effect. We’d expect to see complete 100 percent female sex ratios in these populations, and potentially even really high mortality in the nests of these populations as well.

A nesting painted turtle (photo: F.J. Janzen)

CURWOOD: So you’re talking about one degree Centigrade?

TELEMECO: Yes. We’re actually expecting four or more degrees Centigrade in the midwest over the next century. This mechanism by itself really seems like it’s going to be ineffective.

CURWOOD: And why is that?

TELEMECO: Well, if you think about how temperature changes over the course of a year - it gets warmer in the spring and then levels off in the summer and gets cooler in the fall. You can think of a week in spring, temperature changes pretty rapidly, from Monday to Friday, you might have a big difference in temperature. In mid-July, from Monday to Friday, it might be pretty much exactly the same, it’s much more stable in mid-summer. So if say a female turtle, lays her eggs in the ground, at say, June 1st is the historic nesting date for our Painted turtles, she really wants that temperature to be predicting temperature throughout the nest, especially when the eggs are actually sensitive to temperature as far as determining their sex, and that generally is the middle third of development. For our turtles historically, that would be July. If they advance their nesting date, so say they’re advancing a week or two - now they’re nesting in mid-May. The nest’s temperatures are warming a lot more rapidly. While they might plant the eggs in the nest at the exact same temperature, on June 1 and May 15, because of climate change, the actual temperature the eggs experience by that middle-third of development, which is now mid-to-late June, is actually quite a bit higher than they historically were in July. What it basically means is that the females might be nesting at the exact same temperature year after year while nesting earlier, but because of this more rapid increase in temperature early spring, later in the development, the nests are actually warmer than they were before climate change, even with these barely massive shifts in female nesting behavior.

CURWOOD: Because no one has told the turtles that, “by the way, maybe your eggs are going to be a lot hotter in the middle of July, so maybe you ought to lay them even earlier.”

TELEMECO: That’s correct.

CURWOOD: What about evolution? Turtles have been around for over 200 million years surely there must be a way they can adapt.

Rory Telemeco with a Southern Alligator Lizard (photo: M.S.C. Telemeco)

TELEMECO: There are many ways turtles can evolve and adapt to a changing environment. The challenge is going to be that climate change is occurring so very rapidly. We’re expecting changes of four to eight degrees C within 100 years. And these turtles are fairly long lived. It takes them five years to be reproductive, and they can continue to survive and be reproducing every year, for another 20 to 25 years, and that rate of generation time really slows the ability of populations to evolve. It means that you would need dramatic evolutionary changes within just a few generations for them to be able to cope with the types of environmental change we’re predicting over the next century.

CURWOOD: Rory, what if anything, can we do to prevent this?

TELEMECO: Ideally, we would cut back emissions, and do all the things that numerous political activist groups have defined. We’re not going to be able to completely stop climate change, but pull it back and keep the climate from changing so much. Short of that, the things we can do to help support these organisms, or to keep them from going extinct at least, are the same things we would do under any other circumstances. But it’s going to be really difficult and sadly, I really don’t think we’re going to be able to save all of them.

CURWOOD: Rory Telemeco is a biologist at Iowa State University. Thanks for taking the time.

TELEMECO: Thank you very much for having me.

Related links:

- Rory Telemeco’s page at Iowa State

- Read the turtle research paper here

[MUSIC: Josh Roseman “Purple Turtles” from New Constellations Live In Vienna (Enja Records 2007)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...How to harvest early in the springtime - and find a wife - with a backyard city garden.

TOENSMEIER: We wanted to find some sweethearts and we felt like we’d have better luck in the city than we were in the country where we were probably more likely to run into a bear than a woman. And we wanted a place as beat up as you could because we wanted to sort of set the bar high and say, well, “if we can do it, then you can totally do it.”

CURWOOD: Some secrets of permaculture are coming up next on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Carla Bley: “Funnybird Song” from Dinner Music (Watt Works Records 1977)]

[MUSIC: Josh Roseman “Purple Turtles” from New Constellations Live In Vienna (Enja Records 2007)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...How to harvest early in the springtime - and find a wife - with a backyard city garden.

TOENSMEIER: We wanted to find some sweethearts and we felt like we’d have better luck in the city than we were in the country where we were probably more likely to run into a bear than a woman. And we wanted a place as beat up as you could because we wanted to sort of set the bar high and say, well, “if we can do it, then you can totally do it.”

CURWOOD: Some secrets of permaculture are coming up next on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Carla Bley: “Funnybird Song” from Dinner Music (Watt Works Records 1977)]

Alligators All Around

An Alligator named Saul Bellows (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. So the threat of a skewed sex ratio that climate change may bring to many turtle species would also apply to crocodiles and alligators. But as writer Mark Seth Lender found at St. Augustine Alligator Farm and Zoological Park, at least for now, passion still rises in the blood - even when that blood is cold.

Armed to the teeth (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

LENDER: Spring clings to the Spanish moss. Comes up from the swamp in sheaves of mist. It brings the nesting herons home. And raises the blood in an ancient’s bones.

Alligator swimming at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm and Zoological Park (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Big

Bull

Alligators.

Breaking out.

Wake up from the wintery mud where they sleep alone. Slide into that swamp they call home. They stretch, halfway out of the water and expand their throats like over-stuffed pockets. And all around, that water starts to dance. Like spit on a griddle. Like ants in your pants. Like boiling oil. It doesn’t have a choice - the bigger the 'gator the deeper the voice.

Alligator tail (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

But down where the dancing starts it’s only silence humans can hear. I know. I’ve ducked my head below where a person ought not to go, and listened: the only thing that greets your ears is the scrape and the rake of alligator toes. Only another 'gator knows what all that dancing means...

An alligator rests her head on another’s back (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

She hears (what you can only see) and moves on over to the alligator of her dreams. Ignited by her cold-blooded heat he burns, and bellows all the more. Her emotions bulletproof, close to the vest, but when all is said and done she leans her head upon the leather-studded back above his massive chest. Completely still. You can barely see her breathe, or him.

Alligator eye (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Possession is a two-way street when all the lovers are armed to the teeth!

(photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Mark Seth Lender is the author of Salt Marsh Diary. To see some of his photos of alligators bellowing, sidle on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s Website

- St. Augustine Alligator Farm and Zoological Park in Florida

[MUSIC: Frank Macchia “Alligators” from Animals (Caucophony Records 2004)]

Romance and Spring Harvest At Paradise Lot

Asian pears growing in Holyoke, MA (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

CURWOOD: So at this time of year an alligator's fancy turns to thoughts of love, but in much of the country, a gardener's thoughts turn to seeds and weeds and mulch. For many folks, that probably means not more than a few bedding plants and tomatoes. But for permaculture gardeners Eric Toensmeier and Jonathan Bates, spring is a time of bounty, because that’s when leafy perennial vegetables are already at their prime. Eric and Jonathan’s new book, Paradise Lot, is the true story of their experience building a perennial forest garden in a degraded back yard in gritty Holyoke, Massachusetts. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb went to chomp her way through their garden.

BASCOMB: From the street, this gray duplex doesn’t look like much. But around the back is an urban oasis. The yard is just one-tenth of an acre but produces almost all of the fruits, vegetables, and eggs two families need. Eric Toesnmeir took me on a tour of his garden.

The view from above the gardens. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

TOENSMEIER: This is the season of perennial vegetables, vegetables that come back every year and make food. So, down here is Turkish rocket. It looks a bit like a dandelion this time of year but soon it will make these wonderful broccoli rabes, like an 8 or 10 inch mustardy tasting broccoli that are absolutely delicious.

BASCOMB: Eric says what he and his gardening partner Jonathan Bates have created is a permaculture food forest.

TOENSMEIER: So we’re trying to in this area imitate the structure of a forest with trees and shrubs and herbaceous species and vines and fungi but have them be both edible for us and working together as an ecosystem.

BASCOMB: At the lowest level there’s the broccoli - and ramps, ginger and violets. Above them grows a gumi bush, one of their many Asian species. It fixes nitrogen and produces berries that taste a bit like rhubarb. Shading over them all is an American persimmon tree.

A goumi bush fixes nitrogen and provides small red fruits. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

TOENSMEIER: Permaculture is meeting human needs while improving ecosystem health.

BASCOMB: Eric says when they bought the house, the yard needed help. All it would grow was crab grass.

TOENSMEIER: We had three different kinds of terrible soil. There was sand and gravel fill and there was a compacted clay with chunks of concrete and rebar in it, and the last piece where we are now was a sandy acid soil with low levels of lead.

BASCOMB: Eric and Jonathan took one look at this barren plot of bad soil and felt inspired.

TOENSMEIER: We actually thought it was perfect. We wanted to be somewhere where the scale at which we were operating was really relevant to lots of people. So we were looking to be in the city. We wanted to find some sweethearts and we felt like we’d have better luck in the city than in the country where we were more likely to run into a bear than a woman. And we wanted a place that was as beat up as you can imagine because we wanted to set the bar high and say, “well, if we can do it then you can totally do it.“

BASCOMB: So what should we look at next?

TOENSMEIER: Oh, let’s visit the chickens then.

Chickens are an integral component to the health of Paradise Lot. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: Yeah!

[CHICKENS CLUCKING]

TOENSMEIER: So, these are our girls. We have three chickens and they’re a really important part of our backyard ecosystem. We feed them lots and lots of leaves from the garden, excess vegetation both from our own crops and weeds and they love it.

BASCOMB: Eric picks a handful of weeds and feeds them to the chickens through the fence. And he says the bulk of the chickens’ food comes from garden weeds and bugs.

TOENSMEIER: I feel like we wouldn’t really be able to do our garden well without them. It’s so important for them to take the excess biomass that’s produced in the garden and convert it into stuff we can eat directly like eggs and eventually meat, and all this fantastic material that we are standing in right now. The bedding plus manure plus weeds accumulates into a great big deep layer by the end of the year and that is beautiful compost material and they’ve sped up our fertility cycling very dramatically.

BASCOMB: Do you name your chickens?

TOENSMEIER: We don’t.

BASCOMB: Probably a good practice.

TOENSMEIER: Any animal you are going to eat you don’t want to name - unless you name it Christmas or Thanksgiving for the meal at which you will eat it.

BASCOMB: How many eggs do you get a day?

TOENSMEIER: In the summer each one lays one egg. In the winter none of them do. In the spring and fall are sort of in between. They average 220 eggs apiece per year. So, that’s quite a lot. It makes a big difference in our diet.

BASCOMB: Though the chickens are vital, there is a problem.

TOENSMEIER: It’s completely illegal to have chickens in Holyoke. We didn’t have any trouble with them initially and then at one point our previous next door neighbors over here were raided for selling drugs. While the police were here for that they called in our chickens, which is about an equivalent crime of course…three chickens and selling cocaine! So we took them away to the country for a couple weeks until the heat cooled down, and then we brought them back. What we were told if there’s another complaint we would get a $25 fine and we sort of felt like we could live with that alright.

BASCOMB: I would think too you could probably buy off the neighbors with a couple of eggs.

TOENSMEIER: And strawberries. Strawberries are the best bribe we have.

Eric says fresh, organic strawberries are the best bribe they have for neighbors. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: What else should we see now?

TOENSMEIER: Let’s go visit the bamboo grove and the best fruit production area we have in the back corner.

BASCOMB: Sounds good.

[WALKING]

BASCOMB: We walk down the wood mulch path to a corner where tall thin bamboo reeds rustle in the wind. It’s a dense grove that creates a private space in the garden. Next to is the fruit orchard.

The yard was a blank slate when they bought the house. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

TOENSMEIER: This is our Asian pear, it’s just flowering fully for the first time today. We don’t have a lot of room so it’s on a dwarfing root stock that keeps it really small. And it has three different varieties grafted on to it, an early season fruit, a mid season fruit and a late season fruit all on the same tree.

BASCOMB: They get about 150 pears a year, not too shabby for a tree just 12 feet high.

TOENSMEIER: In the same area we have blueberries and service berries, and raspberries, and hazelnuts, and grapes, and rhubarb, and perennial leeks, and elephant garlic, and strawberries so in just this tiny corner which is about 20 by 25 we have all those different plants fruiting and producing excellent food for us.

BASCOMB: Such diversity is impressive and I can’t help but compare it to my backyard garden. The only things I have growing are some pea plants and weeds. But Eric says anyone can create this kind of garden. Just start with something simple.

TOENSMEIER: I think if people are going to start with one thing it would be berries. They don’t take up a lot of space. A lot of them can handle some shade. They’re beautiful, they taste good and they’re mostly very easy to take care of. And every year you can add another bed. We didn’t do all this in one year either.

Old logs do double duty as mushroom habitat and borders for garden beds. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: The garden beds are bordered with old logs. They’re inoculated with spores to grow edible mushrooms but Eric says they also form a critical habitat.

TOENSMEIER: When you roll one over all kinds of creepy crawly things come out which are part of our decomposer ecosystem and they’re part of our pest control system as well. A lot of predacious ground beetles, for example, live under the logs and then go out and eat pests and even eat weed seeds.

BASCOMB: And the system works. In seven years they’ve never had to use pesticides of any kind in the garden. Instead they provide habitat for garden helpers like ladybugs and praying mantises. But, Eric says, it’s wasn’t just beneficial insects that he and Jonathan hoped their garden would attract.

TOENSMEIER: One of our goals for the garden was to attract mates. We felt like the birds that put shiny things in their nest to attract a mate. We planted fruit trees. It’s not like we literally thought that would be all someone was attracted to obviously, but it doesn’t hurt to distinguish you in the market place of other potential mates if there’s something unique and interesting and delicious about you and your backyard.

Eric and Marikler were married in the bamboo grove of Paradise Lot. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

Jonathan and Meg tied the knot at Paradise Lot. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: And that worked too. Next to the bamboo grove beneath a flowering mimosa tree, Eric married Marikler and Jonathan married Meg.

[WIND IN THE BAMBOO]

BASCOMB: As if on cue, Jonathan joins us between the bamboo and the greenhouse.

BATES: My name is Jonathan Bates and I’m a co-gardener here with Eric and landscape. He’s been a mentor for over 10 years now.

BASCOMB: And they’re constantly experimenting. Jonathan designed and built the greenhouse where they grow some annual vegetables and tropical plants.

BATES: We were able to overwinter a hardy avocado and it’s already grown six inches since spring started in there.

Spring time at Paradise Lot. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: You’re growing avocado in Massachusetts?

BATES: Yeah.

BASCOMB: I’ve got to see that.

BATES: We can go check it out.

BASCOMB: Great.

[WALKING]

BASCOMB: Inside the greenhouse it’s humid and much warmer. Jonathan says walking in here is like going on vacation.

BATES: Instead of spending a couple thousand dollars going to Florida with the family for a week, we invested that money in building this greenhouse and now we’re living in northern Florida. So we have things like citrus, Chilean guava, fig, hardy avocado; these are called tree collards. They get to be 11 feet tall and they are perennial - they grow them all year round.

BASCOMB: Recycled granite curbstones define a raised bed inside the greenhouse. There’s also three large tanks containing an aquaponics system with catfish and 800 gallons of water. Jonathan says the granite and the water collect heat during the day and radiate it back at night to make the greenhouse up to 10 degrees warmer.

[RUNNING WATER, PUMPS]

BASCOMB: They plan to expand the system and grow more fish for food in the future, but right now there are plenty of things ready to eat and they’re eager for me to try them. Jonathan tears out a handful of watercress.

[TEARING WATERCRESS]

BATES: It’s a little spicier now because it’s about to go to flower but we had a good three month run for the watercress.

BASCOMB: Mmm…it’s pretty bitter.

TOENSMEIER: There’s tree collards in here to eat right now but if we come outside we have garlic chives.

BATES: We can get some violet flowers for you.

[PICKING FLOWER FOLLOWED BY FAINT CHEWING SOUND]

BASCOMB: Mmm… they’re sweet.

BATES: Here’s some miner’s lettuce. We don’t have a lot of it but they’re good to eat.

BASCOMB: Oh my gosh, a carrot!

TOENSMEIER: These are real nice. These are last year’s carrots. This is Nantes which is like a sweet dessert carrot.

BASCOMB: A dessert carrot. You talk about it like it’s wine!

TOENSMEIER: We’ve sort of started to become connoisseurs of different vegetables here, which is really fun.

BATES: Do you like sorrel?

BASCOMB: I don’t know.

BATES: Let’s try it.

[CHEWING SOUND]

BATES: So, it’s lemony tart.

BASCOMB: Mmm! It’s tart! [LAUGHS]

BATES: You can tell that we don’t eat a lot of it.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I can see why! [LAUGHS]

BATES: Do you like black licorice?

BASCOMB: Sure.

BATES: This is sweet Cicily.

BASCOMB: Thank you.

BATES: Mostly we grow it for the flowers that bring beneficial insects but this is a traditional sugar substitute in Europe. And then one last thing I can show you is the water celery. It has kind of a parsley celery flavor.

BASCOMB: Thank you.

[CHEWING]

BATES: This is a very popular tropical herb in Asia, Southeast Asia, grown in the water. Here it can grow terrestrially in partial shade.

BASCOMB: That’s a pretty impressive plant.

BATES: Yeah. Did Eric show you the sea kale over here?

Sea kale is a perrenial plant that tastes like brocoli but more tender. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

[WALKING]

BATES: So, you gotta try a floret.

[FLORET CRACKING]

BATES: So, it’s a perennial kale that I think is as good as broccoli, annual broccoli.

[CHEWING]

BASCOMB: Where do you guys get these? I’ve never seen sea kale in my local nursery.

BATES: Originally sea kale was a seed we bought from a seed company way back 10 years ago. So some of these plants are 10 years old. But now if you want to get a sea kale plant you can get them from foodforestfarm.com.

BASCOMB: Is that your company?

BATES: That’s my nursery, yeah. [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: So, the garden has turned into a business for Jonathan. When they started this project they had simple goals…to walk out in the yard and get a handful of fruit each day of the summer, greens every day of the year, and find the loves of their lives. Mission accomplished on all accounts. Jonathan says he knew the garden was a success after five or six years when the plants really took root and started to produce in abundance.

BATES: There’s an explosion of life really and at that point this idea of mimicking a forest ecosystem really hit home. It’s like, we really did it.

BASCOMB: For Eric, success was being able to share the fruits of his labor and inspire others.

TOENSMEIER: Over a thousand people have come and visited the garden and a lot of them have gone home and done this. They buy plants from Jonathan or we send them home with seeds. Being in the city has been really good for building a movement.

BASCOMB: Eric and Jonathan say they might one day move out of their paradise lot to a larger piece of land in the country but for now they are happy to be here, building a grassroots movement growing anything but grass.

(Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

(Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in Holyoke, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Eric’s Blog

- Food Forest Farm

- Paradise Lot Website

[MUSIC: Space Funghi Project “Elektrik Psylocibe Experience” from Elektrik psylocibe Project (Three Sixty Records 2005)]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth...a dam project in Ethiopia threatens the river that thousands of indigenous people depend upon.

LOYELI: This river is like our cow that we milk every time and this never gets old, so the government is trying to take our cow and now we will be starving.

CURWOOD: Energy and development versus traditional life-styles - next time on Living on Earth.

[ALLIGATOR BELLOWING]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week amid the slithery and leathery critters that Mark Seth Lender observed in Florida’s St Augustine Alligator Farm and Zoological Park. As Mark explained, when bull alligators bellow, the subsonic part of their vocalization makes the water around them boil.

[ALLIGATOR ROAR]

These low frequencies carry considerable distances, a calling card to females and a warning to other males. Mark recorded the part we humans can hear, and found those sounds just as impressive.

[Earth Ear: Alligators recorded on location at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm and Zoological Park Florida, by Producer Mark Seth Lender]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Alicia Juang, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director.

Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org. And check out our Facebook page, it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield, working to produce healthy food for a healthy planet. Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from you our listeners, The Go Forward Fund and the Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth