September 13, 2013

Air Date: September 13, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

EPA Scraps Chemical Safety Rules

View the page for this story

Blocked for years by the White House Office of Management and Budget, two chemical safety rules have been dropped altogether by the EPA. Environmental Defense Fund’s Richard Denison tells host Steve Curwood why this is bad news for public health. (06:45)

Shrinking Natural Gas Royalties

View the page for this story

Farmers struggling to make a living from their land have welcomed gas companies that want to drill for natural gas on their property. Yet all too often royalty payments don't measure up to the promises. Reporter Abrahm Lustgarten of ProPublica tells host Steve Curwood about his investigation. (06:45)

Cooling with CO2

View the page for this story

Most refrigeration relies on a potent group of greenhouse gasses called HFCs. But John Mandyck of United Technologies tells host Steve Curwood that his company has developed a new technology that can cool shipping containers using C02 directly from the atmosphere. (07:05)

Sustainable Shrimp Farming

/ Naomi ArenbergView the page for this story

The United States imports over a billion pounds of shrimp annually. Most of it arrives frozen from environmentally destructive tropical farms. Now U.S. shrimp farmers are using environmentally friendly techniques to produce a fresh, delicious product with a much gentler environmental footprint. Living on Earth’s Naomi Arenberg reports. (11:45)

Tapir Scientist

View the page for this story

Sy Montgomery spends her life exploring the world of animals and writing about her adventures. She tells host Steve Curwood about her latest book, chronicling an expedition with a scientist trying to save South America's largest mammal, the endangered tapir. (11:30)

Hummingbirds in the Canyon

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Many varieties of hummingbirds gather to feed in Arizona's Madera Canyon. Writer Mark Seth Lender found they tolerated his presence - but were intolerant of other hummingbirds. (02:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Richard Denison, Abrahm Lustgarten, John Mandyck, Sy Montgomery

Reporters: Naomi Arenberg, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Years of White House delay on rules to label potentially hazardous chemicals puts consumers at risk.

DENISON: This kind of uncontrolled experiment we have been running for the last several decades of exposing people to more and more chemicals without requiring evidence that those chemicals are safe is likely to be having a significant impact on our health.

CURWOOD: Also, raising shrimp far from the ocean.

TRAN: See how nice they are? About to jump…Look at that…Whoa!

[LAUGHTER]

ARENBERG: Where’d he go?

TRAN: Very jumpy, very active.

CURWOOD: New methods of raising healthy sustainable US shrimp.

TRAN: Very beautiful type of animal, and we can do this 365 days per year, regardless of weather.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

EPA Scraps Chemical Safety Rules

PBA can be found in many common household products, including the lining of some food cans (photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Certain synthetic chemicals can mimic hormones and disrupt human health and development, but the Obama Administration is now blocking rules that would label such chemicals and require public notification of the results of any research on their health effects. The EPA proposed the rules years ago, but it has now decided to withdraw them after they were bottled up in the White House Office of Management and Budgets, or OMB.

The Senate Judiciary Committee has been investigating what it calls the “human cost of regulatory paralysis,” and scientists at the Environmental Defense Fund and other NGOs are urging the Senate committee to probe why these rules were dropped. Richard Denison of the Environmental Defense Fund explained the significance of the rule regarding hormone mimicking chemicals.

DENISON: So this was a pretty simple rule that would simply have had EPA identify publicly several chemicals to be officially deemed chemicals of concern based on a finding that these chemicals may present a risk to human health and or the environment. And they proposed to list bisphenol A, some phthalates that are used as plastic additives and in cosmetics and other products, and some brominated flame retardants used in furniture foam and computer casings and the like.

CURWOOD: Well, what is the current scientific thinking about bisphenol A and phthalates and those flame retardants? What are the dangers?

Richard Denison (photo: Environmental Defense Fund)

DENISON: So each of those chemicals is increasingly of concern because of evidence that even fairly small doses of these chemicals can interfere with our normal functioning of the systems in our body that keep us healthy. These chemicals act by manner that are similar to the way in which hormones act in our bodies, and they can actually interfere with the normal development of our reproductive system, our neurological system, our immune system and so forth. The developing fetus and infants and very young children are particularly susceptible to those effects. This is all new science, and there’s a lot of research that still needs to be done, but I think it’s a major warning sign that the evidence that the evidence those chemicals are safe is likely to having a significant aggregate impact on our health.

CURWOOD: Tell me about the other rule. I understand it would compel companies to divulge more about the ingredients in their chemicals, if I have that right?

DENISON: That’s close. What this rule would have done is to require that if a company submitted a health and safety study on a new chemical to EPA, that study would have to be made public, and the identity of that chemical that was the subject of the study would also have to be made public. There’s a tension between company’s legitimate interest in protecting the identity of the chemicals that they’re developing before those chemicals get on the market, and the competing interest of the public and workers and consumers to have a right to know about the health and environmental impacts of chemicals they might be exposed to. I think that made this rule controversial, and it ended up in limbo for two years - excuse me, almost four years - in the review process at the White House, and ended up being one the two rules that EPA withdrew last week.

CURWOOD: Now, this isn’t an unique situation: a number of rules have been held up by the White House regarding the EPA.

DENISON: That’s right, Steve. These two rules being withdrawn are indicative of a much broader systematic delay by the White House in reviewing rules that EPA is developing under clear statutory authority. So the dispute here is not whether or not EPA has the authority to issue rules; the dispute is over the ability of a White House office to interfere with the normal rulemaking process that EPA would otherwise have to follow.

Many of these proposals that are languishing at OMB, or have been under review far longer than the executive order that gave OMB this power allow are simply proposals that have yet to be even vetted through the public comment process that is the norm to be used with every rule that gets developed. That ought to be the way the process works instead of a small office buried within the White House behind closed doors simply sitting on these rules and refusing to clear them so that they can be proposed for public comment. That’s a very non-transparent and I think non-democratic process and yet it’s become a routine practice especially with EPA rules governing chemical safety.

CURWOOD: Why do you think the Obama administration, an administration that pledged to have transparency in these agencies, is backing down on this type of rulemaking?

DENISON: Well, it’s baffling. It’s a very good question, Steve. I do think in general there’s been lots of pressure coming from Congress to scale back regulations, and I think in some ways probably some of this response by the White House has been a political one.

The tragedy here though is these are not examples of heavy command and control regulation. In fact, the power of EPA’s using this authority to simply tell the market these are chemicals of concern, and we expect that if you’re going to continue to want to use them or produce them, you need to be providing the information necessary for us to determine that those uses are safe, that would have sent a very good signal to the market that, in fact, there’s growing concern about these chemicals, and that it should be the onus of those who want to continue to use them to demonstrate their safety rather than consumers in the public bearing the burden should they prove to be unsafe.

CURWOOD: Richard Denison is a senior scientist with the Environmental Defense Fund in Washington. Thanks for joining us today.

DENISON: I'm so happy to have been here, Steve. Thanks so much.

Related links:

- Richard Denison’s page at the Environmental Defense Fund

- Read the Richard Denison’s blog post on the EPA’s decision

- Read the letter that Richard Denison and others wrote to the Senate Judiciary Committee

[MUSIC: Steve Gadd “Who Knows Blues” from Gadditude (BFM Jazz 2013)]

Shrinking Natural Gas Royalties

Natural gas drilling on Pennsylvania farmland (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: The practice of hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” for natural gas has generated an energy bonanza for the US, and for some landowners it has also generated a lot of cash in the form of royalties.

But fracking has also caused a lot of controversy and now the investigative reporting group ProPublica has found that some landowners are waking up to an unpleasant surprise, as they find their royalty payments are suddenly being slashed.

Abrahm Lustgarten has been looking into a number of these cases, including that of Pennsylvania farmer Don Feusner.

LUSTGARTEN: Don has a farm on the northern edge of Pennsylvania right near the New York border. He has a couple hundred acres, and he had farmed that land with dairy cattle for a number of years and has had much of the same difficulty making a living from farming as many other farmers in the United States. And so when the landmen for the gas companies came knocking on his door inviting him to allow him to drill on his land and promising him huge rewards to do so, he agreed. They drilled two wells on his property, and they struck payday. Two of the most prosperous wells in the area were on his property, and they started producing millions of cubic feet of natural gas.

CURWOOD: So what did this mean for him financially?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, it should have meant that he was set for life, and the first couple of checks that he received after that production began were pretty good. He was looking at anywhere between $6,000 and $10,000 a month in income from his share of those wells. He’s entitled to get about 12 and a half percent of the value of the gas that’s produced on his property. But then in the early part of 2013, his checks began to dramatically decrease. The company, Chesapeake Energy, was deducting expenses from his payments, and those expenses began to increase until they amounted to just about 90% of the income being produced from his well.

Fracking well (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: So walk me through the numbers here, Abrahm. Let’s say that $100 worth of gas comes off of Don Feusner’s land. What was he expecting to get paid, and what is he now getting paid?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, speaking in rough numbers, his contract would have entitled him to about $12.50 out of that $100 of income. Instead, he’s getting about $1.25 for that unit of gas - about 90 percent less than he expected when he signed his contract.

CURWOOD: So where is the rest of his money going?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, that’s really the big mystery. Chesapeake Energy tells Don Feusner that the deductions for expenses out of his paycheck go towards what they call “gathering”. Gathering is the process the natural gas industry uses to take the gas produced from the well head and transport it to some point of sale, some big pipeline off at a port or somewhere else like that. But they won’t really specify anything more than that. They won’t tell him how those gathering expenses break down, for what length of pipeline or how the numbers add up. And so he really is left being forced to take their word for it.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, Chesapeake is partners with Statoil, the Norwegian company on Mr. Feusner’s land. How much does Statoil give him for their, say, $100 share of gas that they take off his land?

LUSTGARTEN: From Statoil, Don Feusner gets his full $12.50, his full share of the gas there produced. Statoil did not interpret Don Feusner’s contract the same way that Chesapeake Energy did, and essentially told me they don’t believe that they’re entitled to withhold the expenses the way Chesapeake is.

CURWOOD: How common is this type of underpayment that Mr. Feusner’s getting from Chesapeake?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, anecdotally, it appears to be extremely common. Virtually, anybody I asked, from landowners to experts who work for landowner advocacy groups or accounting firms across the country tell me basically that this happens all the time. One executive at a major banking institution estimated about 70% of American landowners are severely underpaid for the oil and gas that are produced on their property.

CURWOOD: So Don Feusner saw his monthly check go from $6,000 to $10,000 down to $1,000 from Chesapeake. What kind of impact has it had on him?

Abrahm Lustgarten

LUSTGARTEN: Well, he can’t retire, which is what he initially hoped to do when he got out of dairy farming. And he basically says that the income he’s receiving today from drilling more or less compensates him for the inconvenience - the trucks, the machinery on his land, the pipeline running through his land. He’s certainly making a little bit of money still, but not enough that he feels like it clearly has been beneficial to him and his family.

CURWOOD: So what kind of recourse does he have here?

LUSTGARTEN: He’s very limited. Like a lot of Pennsylvania landowners, his lease stipulates that he cannot sue Chesapeake Energy. He’s required to go through arbitration. He’s right now talking with lawyers to see what his options may be. If he can find, or his lawyers can find, a number of people who have the exact same lease as him, then he may be able to go into arbitration with a group. But long story short, it’s a very uphill battle. He should expect to spend tens of thousands of dollars just to begin this argument, and he has a very good chance of losing if he does.

CURWOOD: So what’s he going to do now?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, he sounds disappointed and resigned to his current situation. And that’s more or less what he says others in his community are thinking and saying at this point in time as well. So this is a large swath of northern Pennsylvania where people expected really a huge economic boost across the region, and while there’s certainly some money flowing in, and there are individuals who are making a lot of money, the general consensus at this point seems to be that they will not ever see the kind of money that they expected or hoped for.

CURWOOD: Abrahm, before you go, tell me, how has your reporting influenced what you think about the fracking debate in the US?

LUSTGARTEN: Certainly, there’s environmental issues that come up when we talk about drilling that I’ve reported extensively on that have opened my eyes to the extent of environmental ramifications and change that can be brought by the drilling process. You know, throughout that debate over the environmental implications of drilling, the balancing side of the scale was always supposed to be the economic boost that drilling would bring. So perhaps a trade-off - some environmental problems in exchange for, you know, economic stimulus that’s really needed in a lot of these rural and somewhat impoverished parts of the country.

This investigation, this discovery that landowners are so underpaid - I honestly found quite surprising. I mean it really undermines a lot of the argument for how small people, if you will, for how average American citizens will benefit from oil and gas drilling. And so I think there’s a real mismatch in terms of the average landowner, what they expect when a landman shows up at their door and promises them millions of dollars for drilling, and what actually happens when those landowners go toe-to-toe with some of the biggest companies in the world.

CURWOOD: Abrahm Lustgarten is an environmental reporter with ProPublica. Thanks so much.

LUSTGARTEN: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Despite repeated requests before we went to air, Chesapeake Energy had not responded to our request for comment.

Related links:

- Read Abrahm Lustgarten’s ProPublica article

- Abrahm Lustgarten’s page

[MUSIC: The Brooklyn Funk Essentials “By And Bye” from In The Buzzbag (Doublemoon Records 1998)]

CURWOOD: Coming up --the green side of CO2 for environmentally friendly cooling. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Steve Cropper: “Opus De Soul” from Jammed Together (Stax Records 1969)]

Cooling with CO2

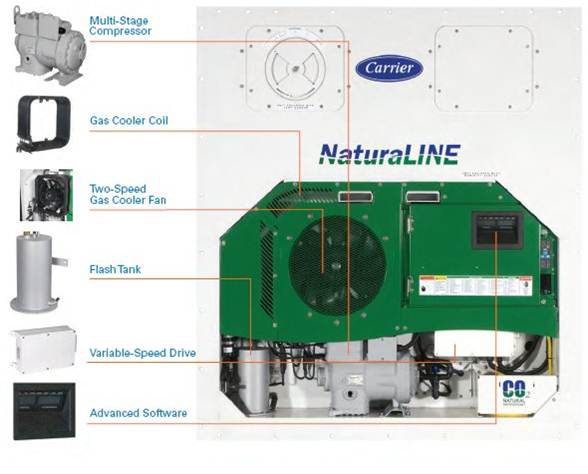

Shipping containers with UTC’s new cooling technology (photo: United Technologies)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

First Dupont’s Freon cooled things down - until it was discovered that chlorofluorocarbons or CFC’s make holes in the ozone layer that protects the earth from damaging ultraviolet radiation.

In the 1980s came the Montreal protocol that banned CFCs, and industry replaced them with hydrofluorocarbons or HFC’s. HFC’s are ozone friendly, but it turns out they are also powerful greenhouse gases - up to twenty thousand times more potent than CO2.

So in June, China and the US agreed to phase down HFCs, and since then, 33 more nations and the EU have joined in. The Carrier division of United Technologies was ready to meet the challenge, with plain old carbon dioxide. John Mandyck is UT's Chief Sustainability Officer.

Diagram of the cooling technology (photo: United Technologies)

MANDYCK: We've developed and pioneered a new refrigerant for marine container applications, these are ship-board containers that cool produce, cool food, cool computers. And the technology that we’ve pioneered is actually taking CO2 itself and using it as a refrigerant.

What we do is we take recycled CO2, CO2 that's been pulled out of the air, and as we know CO2 is a problem for climate change. But we’re actually repurposing it and turning a problem into a solution, by operating it under high-pressure and turning it into a gas that provides cooling, and it's actually proven to be a very effective technology for marine container applications.

CURWOOD: Well, how much greener is using CO2 for cooling rather than HFCs, the hydrofluorocarbons?

MANDYCK: Well, in the case of marine containers, we’re able to reduce the carbon footprint by 35 percent. So that's a meaningful reduction that comes in two forms: A, we've been able to match the best in class energy efficiency using CO2 which has been a technical challenge here to now, and then B, we’re replacing a higher global warming refrigerant, as you've mentioned, with one which is much lower on the global warming scale.

CURWOOD: So the coolant itself and your process is net-zero when it comes to the climate right? You’re taking it out of the air, and if it were to escape it would be back into the air.

MANDYCK: That's exactly right.

CURWOOD: But there's the energy involved in this process.

MANDYCK: Yes.

John Mandyck with Living on Earth host, Steve Curwood (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: Let’s do some basic science here. How do you cool something using energy?

MANDYCK: Well you use energy typically to operate a compressor. The compressor compresses gas, and when you compress the gas it releases the cooling effect. So that's where the energy comes in is in operating the compressor to cool the gas. In this case you have to operate the compressor in a different capacity because of the gas pressure, and we've been able to manage that process in a breakthrough technology which is the world's first in this application.

CURWOOD: How long have you been doing this?

MANDYCK: Well, CO2 as a refrigerant actually goes back to the late 1800s. It fell out of grace because of these technical difficulties that weren’t able to be solved at that time, and so the industry moved into the chemical refrigerants as we know them today because they were safe, they were reliable, they were stable. What we've come to find out over years though is they have other side effects that we want to now manage. So we’ve gone back to where we were to re-examine CO2, and with more modern technology we’ve been able to achieve this breakthrough.

CURWOOD: Well, let's talk about this history of coolants. We found back in the 1980s that freon was poking a hole in the Ozone layer, as well as being a greenhouse gas...

MANDYCK: Exactly.

CURWOOD: And the Montréal Protocol was put together by nations to eliminate that. And so people have been making greener cooling technologies ever since the Montréal Protocol came together. Tell us a bit more about what prompted your company to get engaged with this?

MANDYCK: Well, we’ve been following the Montreal protocol since its inception, and we’ve been the first to introduce non-ozone depleting technologies across the spectrum. So we know refrigerants very well, and it was really the Montréal Protocol that prompted us to say, ‘Can we find a better solution? Can we push environmental technologies as far as they can go so that we can provide a customer benefit, an end user benefit, but also see if we can minimize our impact on the environment?’ So we started that with the elimination of the CFCs, as you mention, which were known as freon at the time, and we’ve steadily found ways to move the needle and to effect a transition that makes sense. This is a natural evolution of that phase with the introduction of our CO2 technology in the marine container business.

CURWOOD: If all the companies that use refrigerated shipping were to switch to your product, what will be the effect on the carbon cycle for the planet?

John Mandyck with Living on Earth host, Steve Curwood (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

MANDYCK: The shipping industry overall, the International Maritime Organization tells us, will account for about 18 percent of the world's greenhouse gas emissions in 2015. That's up from 3% percent in 2007, so this is an area where we have a growing base of greenhouse gas emissions. On any given day there are 175,000 carrier marine container units operating on the oceans, and those units carry 6 billion dollars worth of goods, and the number one marine container transporter good is the banana. So when people enjoy their bananas in the morning, it’s actually coming to you most likely through a marine container and hopefully in the future will be coming to you in a marine container that is 35 percent less from a carbon footprint standpoint.

CURWOOD: What other applications are there for this technology?

MANDYCK: Well, CO2 is very good at making things very cold, and so it's an excellent refrigerant to freeze foods, or to keep food at a colder temperature at 30°, 40°. It can be mastered and operated very well, very efficiently at those levels, and so in 2005 we debuted CO2 in commercial refrigeration, which is supermarket refrigeration, again a great application. We’ve now taken the technology to marine containers and we’re exploring it in truck trailer refrigeration applications as well. CO2 does not work so well to make people comfortable, so if you want to keep a building operating at the 70° to 72° range, you need more energy to use CO2. So what we found is where it works well or where it doesn't work well, and that helps to inform our product development process.

CURWOOD: Step back for a moment. What lesson should business...should industry on a broad scale take from what you've been able to do here with CO2 using it as refrigerant? There are a lot of complaints that addressing climate change will cost a lot of money.

MANDYCK: The lesson is that technology can solve many of the world's environmental issues that we are facing today. In this case we’ve found a way to use technology, to use innovation, to address the greenhouse gas problem using a greenhouse gas itself. Not all applications lead to that, but technology is the key for us to manage our environmental issues in the future.

CURWOOD: JohnMandyck is Chief Sustainability Officer for United Technologies. Thanks for coming in, John.

MANDYCK: Thank you.

Related links:

- Read about UTC’s C02 cooling technology

- More about UTC Sustainability chief John Mandyck

[MUSIC: Fred Katz “Vintage 57” from Katz And His Jammers (Stardust records 2013 reissue) R.I.P. Fred Katz 2/25/1919 – 9/7/2013]

Sustainable Shrimp Farming

A four-month old Pacific white shrimp. (photo: Naomi Arenberg)

CURWOOD: Back in June I talked with Oceana director Andy Sharpless about his new book called The Perfect Protein, which is all about sustainable seafood. America’s favorite seafood, he said should be off-limits:

SHARPLESS: …and I’m sorry to say, you’ve got to swear off shrimp.

CURWOOD: Shrimp?

SHARPLESS: Yeah, it’s bad news, I’m sorry. There’s no way to get a shrimp and feel good about what you’re doing for the future.

CURWOOD: Virtually all the shrimp we eat is problematic - it's mostly imported frozen from Asia, and raised in environmentally damaging conditions. But now indoor shrimp farmers could turn shrimp into a “perfect protein,” delicious and sustainable. Naomi Arenberg reports from Stoughton, Massachusetts.

ARENBERG: Sky 8 Shrimp Farm is 30 miles from the ocean, and it’s easy to miss. It lies at the end of a rutted road through an industrial park, past a few 18-wheelers, in a brick building. There’s no business sign, just a small, round decal on the side door depicting a shrimp.

[WATER NOISES, SHRIMP SPLASHING]

Jimmy Devine covers Tank 4 to keep the temperature at 85-degrees. (photo: Naomi Arenberg)

But past that door, behind a floor-to-ceiling plastic curtain, the clatter of water pumps, heaters, and fans takes over. There, in a half-dozen round tanks, six-feet high and 12-feet across, live several thousand Pacific White Shrimp.

TRAN: See how nice they are? Look at that…He’s about to jump..Whoa!

[LAUGHTER]

ARENBERG: Where’d he go?

TRAN: He’s right here.

ARENBERG: Poor, little shrimp!

TRAN: Very jumpy, very active.

ARENBERG: James Tran has nurtured this jumpy crop for four months, since they arrived as microscopic larvae. Now they’re a few inches long and strong enough to jump out of the net, bounce off my face, and onto the concrete floor, still wiggling. Tran gently scoops up the renegade and hands it to me.

James Tran shows off his four-month-old Pacific white shrimp (Latin: vannamei) (photo: Naomi Arenberg)

TRAN: There you go.

ARENBERG: It’s like a piece of stained glass. You can practically see through him.

TRAN: Very beautiful type of animal, and we can do this 365 days per year, regardless of weather. If you growing shrimp out in the sun, it’s really hard to control temperature, but within the controlled environment like this warehouse I always set my temperature at 85-degree.

ARENBERG: The farm is Tran’s brainchild, and it was all built by his partner, contractor Jimmy Devine.

James Tran holds up a beaker of shrimp larvae, just two weeks old. (Naomi Arenberg)

DEVINE: There’s zero coastline impact. There’s no discharge.

ARENBERG: Jimmy says that’s another benefit of an indoor operation.

DEVINE: All we do is take the water from the ocean and bring it here. And then after three years we sample the water to make sure it has the proper minerals and solid things that are in there and then continue to use it. So, it’s very environmentally friendly.

ARENBERG: Before we head out of the noisy tank room, James and Jimmy drape a sheet of heavy plastic over the tank. Then they dim the lights.

[PLASTIC CURTAIN RUSTLING]

ARENBERG: You seem very loving toward your shrimp. Do you feel as though you’re putting them to sleep, saying, “Good night?”

DEVINE: You should meet Tone, the other guy that’s not here right now. He takes care of ‘em like they’re his baby. When we put ’em to market, we’re gonna have to ask Tone to go outside while we bring ’em to the store. Yes, he loves them..If he was allowed to swim in the tank with them, I guess he’d get in.

[LAUGHTER]

ARENBERG: Tone, the caretaker, is from Laos, James Tran's from Viet Nam, their consultant is in the Netherlands. Jimmy Devine and the marketing specialist are from the Boston area. Tran’s international team has created something unique in New England, the region’s first shrimp farm. Permitting took several months as state officials had to find their way through an entirely new process. Now the Sky 8 facility’s complete. In the office Tran explains how he maintains his water quality.

Just inside Sky 8 there's a shrine, typical of East Asian businesses. (photo: Naomi Arenberg)

DEVINE: The idea of this project is we using recirculating aquaculture system. It’s a biofloc system. Biofloc, it just a bacteria. It’s also a protein for the shrimp. It does two things. It’s a protein, but it is a bacteria to consume the solid of the shrimp.

ARENBERG: Experts from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration describe biofloc as a community of microscopic organisms, that can include bacteria, algae, crustaceans, and nematodes, and that form a colony. The colony takes in nutrients from the water and turns them into protein and fat which the shrimp eat, along with an occasional pellet of shrimp feed. In turn, the biofloc community consumes the shrimp waste. This symbiotic relationship keeps the water clean and cuts the cost of feed. Tran says the system also provides a bonus perk for the farmer.

TRAN: Probably one year later we will empty it, and, using that flocs, using that waste, you can use that for plant fertilizer. Yeah, I can sell that too. [LAUGHS]

ARENBERG: Tran’s brother is a shrimp farmer back in Vietnam. A couple of years ago Tran, who’s an electrical engineer, was researching equipment for his brother. The more James read about Southeast Asian aquaculture, which is based outdoors, the more interested he got in improving it.

TRAN: I will not suggest to the American people to eat shrimp from import because it’s too dangerous. They use antibiotic, they use chemical. They can raise the shrimp to reach market size, 20, 21, 22 gram, within two months. Mine takes how many months?

ARENBERG: His take much longer - five to six months.

TRAN: Because I don’t use any antibiotic or anything like that. It’s just 100 percent natural.

ARENBERG: And shrimp farmers’ dependence on chemical additives is not restricted to East Asia. Darryl Felder is a crustacean researcher at the University of Louisiana. He says commercial shrimp farming standards globally are low.

FELDER: This is certainly not organic gardening. This is a very technologically intense application of pesticides in order to favor the harvesting of shrimp.

ARENBERG: And Professor Felder says that outdoor shrimp farms alter the environment significantly.

FELDER: The most common, traditional ones and the ones that are propagate the most rapidly to this day are those that utilize coastal, low-lying lands near shore, and often they have been covered with mangroves, and they are tidally floodable. The entrepreneurs that step in to build the shrimp farms will clear the mangroves, and they’ll dig shallow ponds, and then they will stock those ponds with juvenile shrimp that they’ve purchased from a hatchery, they have ’em flown in, and then they’ll feed them over a period of time, using foods that consist often heavily of fishmeal.

ARENBERG: Removing the coastal mangroves destroys both a natural nursery for young fish and crustaceans and protections from storms and coastal erosion. And that’s not all…

FELDER: The effluent from those ponds is having very negative impacts on natural estuaries that may have previously sustained artisanal fisheries for local, indigenous populations. What everyone has hoped for is to get away from that, and to get to something that is a little more self-contained, that recycles the water and yet that produces a very good product.

ARENBERG: That’s just what Tran and Devine are trying to do in New England. As well as building a closed system with no discharge, they’re tackling the feed issue. Traditional fishmeal pellets are made primarily from small fish that never grow up to be harvested for people to eat. The Sky 8 partners are working on their own food formula, which will save on fishmeal and money. Their commitment to environmental responsibility already is paying off, with a number of area restaurants serving Sky 8 shrimp.

COOPER: My name is Eric Cooper. I am the chef at 10 Tables in Provincetown, Massachusetts. We basically run a very seasonal menu with a strong focus on using local produce.

ARENBERG: 10 Tables is an upscale restaurant with locations in metropolitan Boston as well as this one, at the outer tip of Cape Cod. Chef Eric says that his customers have commented on the Massachusetts-raised shrimp he serves.

COOPER: The reaction generally has been very positive. They love the flavor, and a lot of people have commented on how excited they are to be getting shrimp that are, you know, farmed in Stoughton - it’s kind of a funny idea, Stoughton is land-locked, you know?

The only sign on Sky 8 Shrimp Farm's door is a depiction of a shrimp. (photo: Naomi Arenberg)

ARENBERG: A funny idea, perhaps, but the fact that these shrimp are so fresh and local affects affects their taste as well as their environmental footprint.

COOPER: These shrimp are very, very soft and delicate in texture. The flavor is very, very clean. It’s just this magnificent, sweet, pure shrimp flavor, and they are beautiful, like almost translucently clear. Nobody thinks of fish coming from farms, everybody assumes it’s wild-caught, and that’s not something we can do for much longer. I guess, as a chef, it’s something that I try to focus on, I like to make sure that the seafood we’re using is something that we’re not going to be eating the last of.

Chef Eric Cooper in the garden at Ten Tables in Provincetown. (photo: Naomi Arenberg)

ARENBERG: Eric Cooper is part of a movement among chefs who want fresh, local seafood. James Tran says that both Whole Foods Market and East Coast-based Legal Sea Foods asked for exclusive rights to the Sky 8 product, but he turned them down. He feels there’s more quality control with his shrimp in the hands of an individual chef who values the eating experience of his clients, rather than in the vault of a large food operation, even a well-respected one. And now this new farm is gaining wider notice. Barton Seaver is a renowned chef and author, whose work focuses on sustainable ingredients. He has a long and impressive title.

SEAVER: Director of the Healthy and Sustainable Food Program at the Center for Health and Global Environments at Harvard University’s School of Public Health.

ARENBERG: Seaver holds up sky 8 as a model for shrimp farming.

SEAVER: It is mimicking natural systems in ways that are smart, intuitive, and based on ingenuity, and, I think, really represents a great step forward. They’re not just farming shrimp; they’re farming a host of cultures and bacteria and shrimp that act in concert to bring both good economy and good, delicious products to market.

ARENBERG: He says, while biofloc shrimp are more expensive than their tropical cousins that come in frozen, the superior flavor and environmental profile of these fresh shrimp have value.

SEAVER: I think that we need to alter our definition of ‘affordable’ because we spend less on food than any other developed nation in the world. And I think when we broaden the definition of ‘affordable,’ when we broaden the definition of ‘sustainable,’ to ask, ‘What is that we’re trying to sustain?’…Well, the answer is ourselves, our community, our lives, our reality. And so I think that what Sky 8 is doing is very much in line with these principles, in that they’re creating huge value beyond the calories, you know, that we can count with every meal.

ARENBERG: Sky 8 owner James Tran is counting on consumers to recognize that value as well as the potential for broader impact on the economy. He says that the United States outsources billions of dollars every year on imported shrimp.

[SFX SKY 8’S TANK ROOM]

TRAN: My goal and my hope is to build not just only here but other state, because I wanna create job for American people, bring it back here. It’s ridiculous, when we live in one of the world most advanced in technology, and we cannot raise shrimp? Come on, that’s not right. Therefore, I make a determination to push this business as far as I could.

ARENBERG: It’s too early to know exactly how far this business could go. But if his vision becomes reality, then in a few years the menu in your neighborhood restaurant could feature locally grown, sustainable shrimp.

For Living on Earth, I’m Naomi Arenberg in Stoughton, Massachusetts.

CURWOOD: There’s more at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Sky 8 Shrimp Farm in Stoughton, MA

- Marvesta Shrimp Farm in Maryland is another “green” operation.

- Mike Rust, a researcher at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Northeast Fisheries Science Center, provided information for this story.

- Yoram Avnimelech, an environmental engineer at Technion Institute, provided information for this story.

- Information about Barton Seaver’s work

- Information about Darryl Felder’s research

- Ten Tables Restaurants

[MUSIC: Mr. Scruff “Shrimp” from Shrimp EP (Ninja Tune 2002)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...they're primitive, they look like pigs, or ant-eaters -- but they're actually relatives of horses. Chasing tapirs is next on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Trombone Shorty “Vieux Carre” from Say That To Say This (Verve Records 2013)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for the coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Tapir Scientist

Felippe bolts for freedom. (photo: Sy Montgomery)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

We can count on writer Sy Montgomery to bring us funny and fascinating stories of her animal encounters in just about every corner of the globe. Over the years she’s swum with pink dolphins in the Amazon, stalked snow leopards in Mongolia and hugged a giant Pacific octopus - when she wasn’t at home with her 750 pound pet pig, Christopher Hogwood. And recently I caught up with her to hear about her expedition with photographer Nic Bishop to the vast wetlands of Brazil called the Pantanal. Sy was there to chronicle the work of Patti Medici, a scientist who is trying to save South America’s largest mammal, the tapir.

MONTGOMERY: There’s several different species of tapirs but the one that I was writing about is the most common tapir. They look like something prehistoric, and they are, because they have not changed in five million years when we had mastodons running around North America. These guys, they look a little bit like an elephant because they have a trunk - a flexible trunk - although it’s shorter. They look a little bit like a rhino. They are related to horses, and they whinny like horses. But unlike horses, they don’t have hooves. They have toes, and they have different numbers of toes on their front and back feet. They are beautiful; they are stunning, and they’re a keystone species for some of the most endangered habitats in the world, including Brazil’s Pantanal - it’s the largest wetland - and in Southeast Asia as well.

CURWOOD: So this is in South America, the Pantanal, this is a vast grassland.

Leticia and her first calf, Cali. All species of tapirs—even the black and white Malayan tapir—have spots and stripes as babies. (photo: Sy Montgomery)

MONTGOMERY: Right. They call it the Everglades on steroids. [LAUGHS] It’s an amazing, amazing place. And the numbers of birds and reptiles that you see...it’s just a great place to be, full of the voices of strange birds, giant rodents - the world’s largest rodent, the capybara; there’s all kinds of wonderful snakes and caymans, but the birds I think are one of the most astonishing things.

CURWOOD: So tapirs, they’re really important to the ecosystem...why?

MONTGOMERY: Well, one reason is that they love to eat fruit, and they eat some of the fruits that nobody else does. Then they conveniently plant the seeds of those fruits because they eat the seeds along with the pulp. So they eat in one place and they poop in another, and often they’ll go uphill, which a seed would never otherwise do. So they act as gardeners in the forest, and for this reason, they are thought to be super, super important in the ecosystems where they live. But the problem was, until Patti Medici got started studying these, no one knew anything about these mammals, even though they’re the largest mammal in South America, and so crucial to the ecosystems.

CURWOOD: So tell me about this team of scientists led by Patti Medici that you followed around?

MONTGOMERY: Patti Medici was the head of the team. She’s Brazilian, and she started out studying primates, but she felt they were well-studied, and she wanted to go into something new. And she thought, tapirs are just so important, no one knows anything about them. She was going to try to do what no one else succeed in doing before, and study them in each of the habitats where they occur. She goes out about once a month during the dry season in the Pantanal to study them. And for the expedition that Nic Bishop, the photographer I work with, and I joined, there were several other people. It was a multinational, multilingual group.

With radio telemetry and binoculars, Jośe and Pati search for one of the collared tapirs. (photo: Sy Montgomery)

CURWOOD: Sy, now, when you go out on these expeditions, they always turn into a bit of a mystery. There’s a hunt, and you try to find these creatures. These tapirs, they’re big, you say, they’re 400 pounds, but they’re shy, hard to find.

MONTGOMERY: Yes, they’re very shy and hard to find, and they can be extremely quiet, believe it or not, sneaking around on their toes in the forest, or in the grassland. And what we needed to do to study them was to get radio collars on them, and you can’t just walk up to a tapir and ask it to do that. What you usually have to do is to dart them, and there’s two ways to do this. You can entice them into a box trap, which Patti was trying to do - we set up box traps all over her study area. But she also wanted to dart some of them without sending them into a box trap because you don’t want to just get and study the tapirs who are not afraid of box traps.

CURWOOD: Take me through a typical day for a tapir researcher.

MONTGOMERY: Oh boy, none of our days were very typical. A lot of our days were frustrating because when you’re working in the field it’s not like in the laboratory. In the laboratory it’s all about control, but in the field, it’s all about surprise.

We realized that tapirs were going to be hard to find, but we didn’t realize how hard they were going to be to dart, and even when they were in the traps, we were having trouble with the darting working out. We didn’t know why, but several tapirs just wouldn’t go down when we darted them. And we would give them a little more of medicine, and then they wouldn’t go to sleep. Well, you wouldn’t want to give them so much that they’re actually ill. So we had to let some of those guys go.

Other days, we had so many tapirs in the traps that we were afraid we wouldn’t get to them all. It got to be over 90 degrees by 9 o’clock in the morning when were working, and you don’t want to keep a tapir in a trap too long - that’s dangerous.

Other things that happened that were kind of scary and dramatic was we really wanted to be able to get one that wasn’t in the trap because you’re getting somebody that does a different behavior, and Gabriel, our main darter, was working very, very hard at this, but the tapirs always seemed to get away from us.

.jpg)

The team collars a new, healthy tapir. (photo: Sy Montgomery)

Well, the one he got, when it was starting to go sleep, it started going toward water. They’re fantastic swimmers, but you don’t want to send someone to water when they’ve been darted with tranquilizer. And so the whole team ended up getting out and trying to herd this darted tapir away from the water - a 400 pound animal who’s generally very gentle, but they can kill you quite easily if they want to. And if they’re not in their right mind, who knew what would happen. I was so impressed with the bravery of the whole team, because what was most important to them was that they weren’t going to hurt a tapir, and they wanted to prevent him from lying down in the water and drowning, which was successful.

CURWOOD: So looking in your book, you ran into a lot of tapirs out there. What kinds of things did you do with them?

MONTGOMERY: Well, in some cases, we were meeting up with some of Patti’s old friends. Some of them were already collared. She had collared quite a few, but the collars fall off. And also it’s just good to check in with your tapir from time to time.

Others, we knew from seeing their images on camera traps, cameras that are latched to a tree or post, and they snap pictures of all these tapirs as they come and go to areas. And you get to know, oh my gosh, this one has had a baby, and oh goodness, this male is hanging out with this female...I wonder if they’re mating, and this male is following that male...I wonder if they’re chasing him away, and we were following some of them with radio telemetry too. So we got to know, over a dozen tapirs, and their history from these little glimpses that we got of them.

Patricia Medici, the chief field scientist followed in the book, started research on tapirs after first studying primates. (photo: Sy Montgomery)

CURWOOD: So in the end, how did these researchers fare? How successful do you think they were in getting the data they wanted?

MONTGOMERY: Patti said that even though we had a really rocky start and some scary moments, scary that we weren’t going to get a tapir, scary that a tapir was going to get hurt, scary that we almost stepped on a really venomous snake, still this was the most successful campaign ever in terms of getting tons of data. We collected tapir poop, which is extremely important, tapir ticks, also very important, tons, thousands of camera trap photos, we put collars on tapirs who’d never been collared before, we microchipped one of them, and we met up with some of her old friends. So it was an incredible whirlwind two weeks.

CURWOOD: OK. Dangerous snakes you mentioned.

MONTGOMERY: Oh yeah. [LAUGHS] Oh gosh.

CURWOOD: How dangerous was this snake?

MONTGOMERY: This was a snake whose bite is described as dying by inches. It was a Fer-de- lance, they are one of the world’s most venomous snakes, and we were out in the middle of nowhere, the Pantanal. And one of our first nights there, we were out walking in the moonlight looking for tapirs, hadn’t found any. We were jet-lagged, we were tired, and since we just got there, we didn’t want to use up our flashlight batteries so we were walking by moonlight, not using our flashlights. We were walking through an area where there had been lots of cows. There were these round cow pats, and we were so tired we were kicking the cow pats, but one of the cow pats wasn’t a cow pat. It was a coiled Fer-de-lance.

CURWOOD: Oooh my! How close?

MONTGOMERY: We were extremely close. We could have kicked it. The only reason we didn’t, and then, of course, would have had every right to bite us, was the photographer for this book, Nic Bishop, had just done a book on snakes, and his head was in snake mode, and we so nearly stepped on this snake. But it was thrilling to see it.

CURWOOD: You’ve written more than a dozen books. They’re pretty much always about animals. Why?

MONTGOMERY: Well, most of animate creation isn’t humans. I like humans, I married one, and some of my best friends are humans, but some of my best friends are not humans. And there’s lots of people writing about humans. I think there’s been a dangerous disconnect between us and the rest of animate creation. So that’s why I write about those who Farley Mowat calls ‘the others’.

And also, it’s because you can learn so much from someone who’s different from you. Animals, they share a lot of the same emotions that we have I believe neurotransmitters are highly conserved across taxa which means they have the same brain chemistry that we do. A clam that’s being opened will show the same neurotransmitters in its bloodstream - we don’t call their bloodstream blood - that a person having a heart attack does. They’re panicking.

So they have a lot of the same emotions, but they have all kinds of other abilities, you know, octopus can taste with all of their skin, crickets can hear with their knees, a dog can smell someone that passed by a week, two weeks, a month ago. They have all these great abilities. Birds can see infrared light. So animals have always been my teachers, my mentors. And there’s that great Buddhist saying, ‘when the student is ready, the teacher will appear.’ The teachers that have appeared to me have had four legs or six or eight or none, or fur or scales.

CURWOOD: Sy, you usually have a picture of yourself in your books, but there’s a Sy Montgomery, but it doesn’t look a whole lot like you in this book.

MONTGOMERY: No, and I’m hoping this is what comes up when people do Google images for Sy Montgomery. There’s a much more glamorous Sy Montgomery out there. It’s a beautiful, fat, sleek, gorgeous female tapir that was named after me after I had left.

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery’s latest book is called The Tapir Scientist: Saving South America’s Largest Mammal.

CURWOOD: Thanks so much, Sy.

MONTGOMERY: Oh, what a pleasure to see you again.

CURWOOD: There are pictures and more at our website, LOE.org

Related links:

- Video of Patricia Medici lecture in 2011

- More about Patricia Medici’s tapir research

- More about Sy Montgomery

- The Tapir Scientist : Saving South America's Largest Mammal

[MUSIC: Zuco 103/Various Artists “ from Six Degrees Of Brazil (Six Degrees Records 2006)]

Hummingbirds in the Canyon

Hummingbird conflict (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Madera Canyon, Arizona is a famous spot to see a great variety of hummingbirds - if you know where to look. Guided by local expert Bill Forbes, Mark Seth Lender found the elusive hummers and discovered the birds were remarkably tolerant of humans and remarkably intolerant of each other.

LENDER: Like a bee with a buzz with a twist like a top with a sweep with a lunge with a LOUD then stops, right there: Hovering; (Covering); Defending a ground that is Flower that is Food that is Air.

His beak is a lance, his wings are a shout: Beware! Of me! Hummingbird!

Anna's Hummingbird female feeding on cactus flower (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

All of an ounce of anger charges, headlong - chases everyone away. Even the females of his kind. Sometimes, in a rage he will drive her down to the dust and leave her spent, and fluttering. Aerodynamics sets the only limit. His right has no respite, has no bounds. Darts and dives and chitters. Intolerance is his nature; his nature, in a crowd? Never calm.

Broad-billed Hummingbird, male, Acrobatic flight (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Herons and Egrets with great piercing bills; falcons with talons that crush; the terrible saw-toothed beaks of sea birds; the raking feet and spurs of the great birds of the ground – all of them strive against their own but almost always at a distance. They pretend. Noh drama of no-touch. Balinese shadow-play. And when the curtain falls? All grievances are over, and done with.

Broad-billed Hummingbird female vertical flight (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

For Hummingbird, the size of a leaf, the density of a folded pocket-handkerchief the stage is a World and the World is War. Black-chin puffs up the tiny feathers that give him his name into electric purple defiance. Broad-bill, all sapphire and emerald brilliant (even his body glares). Broad-tail, so fierce, brings up the rear - 3grams, no fear.

Black-chinned Hummingbird female backpeddling (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Only Magnificent Hummingbird ignores the worrying by all these others - by weight, and size, and the rumbling spread of his wings. His starlight-turquoise throat glittering in the leafy morning light; he alone owns peace.

Magnificent Hummingbird male feeding (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

So there it is: size matters. I am reminded of that barroom adage (a barroom adage on the wing): Big guy knock you down, but little guy will cut you!

[MUSIC: Carlos Enrique “Hummingbird” from Impressions (Carlos Enrique Music 2008)]

CURWOOD: And using a Phototrap, a special triggering device made by Bill Forbes, Mark was able to capture some extraordinary photos of hummingbirds.

To see them, and find out how you can get one for your own wall at home, buzz over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Visit Bill Forbes’ website

- Watch this video Mark took of a Broad-Billed Hummingbird getting nectar

- Want a copy of hummingbird pictures? Send an email to Living on Earth's Gabriela Romanow and she'll tell you how. gromanow@loe.org

CURWOOD: Next week on Living on Earth, the threats facing endangered Asian snow leopards include the Chinese medicine trade.

MAN: Their bones are very very valuable on the black markets across the region; a single snow leopard could bring $10,000 just for its bones.

CURWOOD: But now the leopards have new allies - Buddhist monks - that's next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. We say a fond farewell today to interns Poncie Rutsch and Erin Weeks.Thank you both for your skill, good ideas and hard work – good luck! Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of Red Tomato, supplier of righteous fruits and vegetables from northeast family farms. www.redtomato.org. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth