November 1, 2013

Air Date: November 1, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

West Coast Action Plan on Climate and Energy

View the page for this story

The US states of California, Oregon, Washington and the Canadian province of British Columbia have signed a pact to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by putting a price on carbon. British Columbia's Environment Minister Mary Polak discusses the agreement and how a carbon tax is working in the province with host Steve Curwood. (08:15)

Jerry Brown and the West Coast Action Plan

View the page for this story

The Golden State already has a cap and trade system to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Governor Jerry Brown tells host Steve Curwood that by joining up with neighboring states and British Columbia, California hopes to encourage the rest of the country to put a price on carbon. (06:20)

Power Shift - Massachusetts Teams Up With 7 States to Boost Electric Cars

View the page for this story

Massachusetts and seven other states, including California and New York, have agreed to work together to increase the number of electric vehicles on roads. Massachusetts Environmental Protection Minister Ken Kimmel says the Bay State will use several strategies, from better charging stations to free parking, to reach these ambitious targets. (06:50)

Gulf of Mexico Ocean Health Update

View the page for this story

Three years after the BP oil disaster fouled the Gulf of Mexico, scientists are still analyzing the effects on the ecosystems. David Levin (luh-VINN) reports that mathematics and computers are vital tools, as well as field work (06:50)

Jim's Bees

View the page for this story

Though we're putting the clocks back and it's growing colder and darker, writer Mark Seth Lender recalls the warmth, sweetness and menace of a recent visit to a bee-keeper. (03:25)

Sharks and Coral - Science Note

View the page for this story

Researchers in Australia have discovered that declining shark populations correlate directly with failing communities of coral. Andrew Keys reports in this note on emerging science. (01:40)

South Pacific Climate Refugee Goes to Court

View the page for this story

Sea level rise could soon make many of small Pacific island nations uninhabitable. Georgetown University Professor Susan Martin tells host Steve Curwood that a man from Kiribati is challenging the international immigration system by seeking refugee status in New Zealand on account of climate change. (07:25)

Beyond the Headlines

View the page for this story

Peter Dykstra, publisher of Environmental Health News and the Daily Climate, discusses some recent environmental stories that didn’t make US headlines with host Steve Curwood, including salt water fouling aquifers in Bangladesh and rare earth mining in Greenland. (04:30)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Mary Polak, Jerry Brown, Ken Kimmel, Susan Martin

REPORTERS: David Levin, Andrew Keys, Mark Seth Lender, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

Regional pacts in North America to cut global warming emissions; a price on carbon; widespread subsidies to support electric vehicles. They're all happening, but not at the federal level.

KIMMELL: I think one of the lessons of environmental politics over the last number of years is that the states are way ahead of the federal government, and we're seeing again an interest in the states leading the way as sort of laboratories of democracy.

CURWOOD: Also, analyzing the bottom of the food chain in the Gulf of Mexico three years after the BP oil disaster to help prepare for future spills.

LENES: We're interested in the bacteria, we’re interested in algae, we're interested in the zooplankton, which are the little guys that eat the algae. So we want to see what is the baseline, and then, when you add oil, how that would impact the algae and the zooplankton.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

West Coast Action Plan on Climate and Energy

Pacific Coast leaders sign action plan on climate and energy. From left to right: British Columbia Environment Minister Mary Polak, Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber, Washington Governor Jay Inslee, and California Governor Jerry Brown. (Photo: Office of Governor Brown)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

President Obama says he wants to do more about climate protection, but Congress is not on board, so states continue to act on their own. And now two major regional climate compacts have been signed, and one even includes a Canadian province. Eight states have banded together to create a common infrastructure for electric cars, and we’ll have more on that later. But first we turn to a deal struck by California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia to coordinate climate policies and put a price on carbon emissions.

The governors of Washington and Oregon have pledged to get laws passed in their states to make burning carbon more expensive. California already has a cap and trade program; British Columbia has a carbon tax. That tax is working well, according to Environment Minister Mary Polak, and she says it’ll work even better as part of this new Pacific Coast Action Plan on Climate and Energy.

Mary Polak is the Minister of Environment for the province of British Columbia. (Mary Polak)

POLAK: For us in British Columbia, we're certainly in a leadership role around the world with respect to action on climate change, but we are a very small population. We’re 4.5 million people, thereabout, so very quickly you can see that when we stack ourselves up against the world, we don’t have a tremendous impact.

By creating this jurisdictional grouping on the west coast of North America, we certainly have a greater potential for influence on world climate change policy, but also we have the opportunity to work together to build things such as a robust clean energy sector, a clean tech sector, and those are kinds of things that work very well when we join our jurisdiction geographically, and we believe that from that, we have the potential to grow and influence even more jurisdictions around in North America and indeed around the world.

CURWOOD: So a big part of this Pacific Coast Action Plan is to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by putting a price on carbon throughout the region, making it more expensive to pollute. How’s that going to work for each of these states, and of course, BC, where you already have a flat tax on carbon pollution?

The Pacific Coast Action Plan on Climate and Energy is comprised of California, Oregon, Washington, and the Canadian province British Columbia. (photo: google maps)

POLAK: Yes, we’ve had a carbon tax, and it’s revenue neutral. We’ve had that in place since 2008. Other regions will do so according to how it fits for their local area. That’s fine with us. Our concern has always been that if we remain the only jurisdiction nearby that had a price on carbon, then that potentially had a negative impact on our business competitiveness. Obviously, we think our model is the best, but we’re pleased with any action that is taken by the other governments, no matter what form, to put a price on carbon and therefore level the playing field.

CURWOOD: Briefly, what has your experience been with the tax? How expensive is it?

POLAK: Well, so our tax currently amounts to $30 per ton. It didn’t start at $30, it started at $10. We gradually increased it over time. Ours is revenue-neutral though, so it means that for every penny in carbon tax that we take in as government, the Minister of Finance is required to put that back out in the equivalent amount of tax reduction, so various ones such as income tax, corporate taxes, small business taxes, and specific taxes geared towards northern and remote residents who have to pay more and have fewer chances to reduce their emissions and reduce their consumption in terms of heating and things like that.

So revenue-neutral...our experience has been that since 2008 our province has bucked the trend in Canada. In fact, our GDP has grown at a faster rate than the Canadian average at the same time, our consumption of fossil fuels has reduced significantly across every fuel type. So it’s easy to do that when your economy’s not growing, but to have your economy grow, and at the same time, reduce your reliance on fossil fuels is not an easy task.

CURWOOD: Can you give me a number on how much reduction?

POLAK: About 15 percent.

CURWOOD: What’s the plan to encourage more use of alternative energy in BC?

POLAK: That’s an important question because when you deal with what is essentially a cultural shift, it’s not just going to be one measure such as a price on carbon that’s going to achieve that. So we have a whole range of initiatives, all the way from incentives for clean energy vehicles to incentives for industry to reduce emissions, and for individuals to reduce emissions. We also, of course, through our purchase of carbon offsets, also contribute to innovative clean energy businesses within British Columbia. Our carbon offset purchases are all required to be within British Columbia, so all of this cycles through and then contributes back into improving our emissions profile in our local jurisdiction.

CURWOOD: Now, right next door to British Columbia is Alberta, home of the Athabasca tar sands. How are you folks getting along?

POLAK: Well, our Premier has been making tremendous inroads with respect to helping Alberta understand our perspective. There certainly is a different culture in Alberta versus British Columbia around petroleum and how we operate with that. But I have to say, fundamentally, there isn’t a large disagreement. Both jurisdictions believe very strongly that we can achieve leadership on climate change while at the same time balancing our need for economic growth to be able to benefit our citizens, earn the revenues that it takes to afford things like health care, education, and other important social benefits. So I don’t think we really start out that far apart.

Of course the highlight right now is the discussions we’re having around the pipeline potential from Alberta to the west coast in order to reach those Asian markets. But those are legitimate discussions to have, and I don’t think they should be viewed as British Columbia and Alberta in an argument more than they should be viewed as British Columbia and Alberta trying to find a solution to the balance you have to strike.

CURWOOD: How are you hoping that the Pacific Coast Action Plan might affect the rest of the United States and Canada?

POLAK: So for politicians to take action on climate change, it’s a risky proposition. They are complex topics to communicate, and often they are difficult in terms of public policy because you’re asking people to take a sacrifice now for a benefit that won’t accrue to them for very many years. It’s not an easy thing for a politician to sell. And as we’ve experienced in British Columbia, having now won two majority elections with our climate policy front and center, our carbon tax front and center, it makes it a lot more palatable for politicians to lead on climate change when they see an example that has actually worked where we can say, “Look. we’ve had the positive benefit we wanted. It hasn’t damaged our economy, and by the way, we actually got re-elected on this basis.” So, every time we can show that an experience has been successful, that gives greater capacity for politicians to move on these issues and to lead on these matters.

CURWOOD: Now, California and the providence of Quebec recently announced an agreement on their cap and trade programs - they both have them. How might Quebec be brought into the Pacific Coast Action Plan?

POLAK: Well, of course, there is the Western Climate Initiative. That’s something that British Columbia is also a part of. These things are evolving over time, and as policy positions on climate change grow and evolve and mature, we’re going to see movement in different areas. I think not only is there potential to bring Quebec into the fold on agreements like this, but we also know from Governor Jerry Brown that California’s been making significant inroads into bringing China, provinces in China, into accords such as this. So there’s tremendous potential.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you for taking the time with me today. Mark Polak is the Environment Minister for the province of British Columbia.

POLAK: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- About BC Environment Minister Mary Polak

- Read the Pacific Coast Climate and Energy Action Plan here

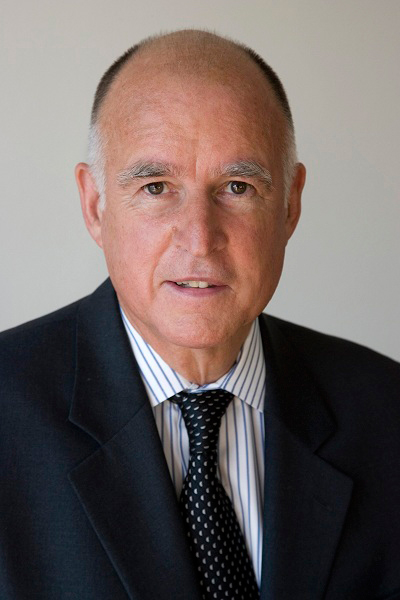

Jerry Brown and the West Coast Action Plan

The states and provinces of the Pacific Northwest share a similar geography and now a goal to put a price on carbon. (bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: With more than 38 million people, California is the biggest and richest member of the Pacific Coast Climate and Energy Compact, and the most advanced of the American states in terms of climate protection laws. So we called up its governor, Jerry Brown, to ask just what his goals are for the deal.

BROWN: The goal here is to reach beyond the border of California and join with the states of Oregon, Washington, and the province of British Columbia and deal with this problem of climate change, global warming and greenhouse gases. This problem is very unique in the sense that no one place, no one state, or even one country can solve it. It takes a lot. It takes everybody ultimately. But in the beginning, we want to spread to as many other states working together to figure out how to reduce climate change.

California governor Jerry Brown (Office of Governor Jerry Brown)

CURWOOD: The big part of your plan is to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by putting a price on carbon. California has cap and trade. British Columbia has a tax on carbon, but what about the other states? How are they going to deal with this?

BROWN: Well, through regulation, for example, by requiring more efficient buildings, by requiring more efficient appliances, different land use rules so people don’t drive as much, encouraging electric cars, encouraging more efficient water use that cuts down on the need for power. There’s many, many things you can do, and, ultimately, of course, putting a price on carbon is essential, but that will take time, and we’re taking the first steps, and we hope over the months and years ahead, we’re going to get to the point where we do all the things we need to.

CURWOOD: Now part of the argument we hear on a national level is, putting a price on carbon is going to hurt business. How do you explain? How do you respond to that?

BROWN: Well, putting a price on something - everything’s got a price. Oil companies raise the price, they lower the price, sometimes putting as much as 50 cents a gallon in the space of 10 months. But we have a problem that carbon going into the atmosphere is trapping heat, which is changing radically and irreversibly the climate on which we all depend. Therefore, we have to reduce carbon emissions, and you do that by laws, by regulations, and by putting a burden on it, called a tax or a price or a fee.

CURWOOD: Why not wait on the federal government to do this?

BROWN: Well, the federal government is currently dysfunctional and paralyzed, and this is an existential threat to humanity. It’s real, and I know there are some deniers out there, many people in the oil business of course, because they’re contributing to the problem in a major, major way. So we have to do what we can where we are. California is 12 percent of the country, and we’re going to start pushing and we’re joining now with other states. We have a memorandum of understanding with various provinces in China. I’ve reached out to different states in Mexico. We can’t wait.

CURWOOD: So how do you bring China into something with California as well?

BROWN: Well, China is involved. The President of China came to California last year. I spent almost an hour with him discussing this very issue. So China is far more active than the United States. They’re the world’s foremost producer of wind machines and solar installations, solar collectors...they’re moving ahead. Now they’re also burning lots of coal, and that’s bad. But in many ways, it’s going to take China and various progressive states in the western hemisphere to join together with Germany and countries in Europe, and that’s the way I think we’re going to turn this thing around.

CURWOOD: So I take it that you expect the Pacific Coast Action Plan is going to affect America, the world, and you’re leading by example here.

BROWN: Exactly. Now, when you put it that way it sounds grandiose. But first of all, there’s no other way forward. It’s either stagnation, give up, or take the lead, and as governor of California, I’m following my predecessors in asserting an important role for the state in curbing pollution, in innovating in so many different ways. So yes, we have a long long way to go. I mean the carbon build up is enormous, it’s constant, tremendous momentum. But California’s a big state. China is suffering from such pollution that, in their effort to combat that, they will develop at the same time technologies and practices that will curb greenhouse gases. So there’s plenty of hope, but it’s not coming from Washington. It’s coming from California, it’s coming from these states that signed up, and British Columbia and China, and there’s Merkel over there in Germany. There’s a lot of positives in the midst of this utter mindless resistance which is so difficult to overcome.

CURWOOD: Before you go, Governor, how do you feel about all this? When you wake up in the morning and think about all your priorities, how do you feel about this one?

BROWN: Well, after I get a cup of coffee...

CURWOOD: Yeah. [LAUGHS]

BROWN:...I feel better.

CURWOOD: OK.

BROWN: There is a feeling aspect to this. But it’s also a matter of assessing where are we in the world, and where are we today in 2013 in the great sweep of history. And we’re on a precipice; if not understood and reacted to will irreversibly degrade the future prospects for everyone, and not just those living in America, and I don’t think that has to be the future. So you ask me how I feel. Well, I feel I’ve got the energy and I’ve got the imagination and intensity to do a lot, having been granted the governorship of California at least for the next year, so I’m making use of the time available to move in another direction against the arrayed powers of fossil fuel companies, mindless politicians and just cynical propagandists, and I believe I see a path forward.

CURWOOD: Jerry Brown is Governor of California. Thanks so much, Governor.

BROWN: OK. Thank you.

Related links:

- Read the Pacific Coast Climate and Energy Action Plan here

- About California Governor Jerry Brown

[MUSIC: Thiefs “Sans Titre (huile sur toile) from Thiefs (Melanine Harmonique recordings 2013)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...taking a look at another pact among the states to fight climate change and perhaps strengthen the power grid at the same time. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Frank Wess: “Low Life” from Jazz For Playboys (Savoy Records 1992 reissue)]

Power Shift - Massachusetts Teams Up With 7 States to Boost Electric Cars

One of the challenges for EVs is building a network of charging stations that will help potential users get over their fear of running out of power. (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. This week, another in our series Power Shift, about the transition to low carbon energy in the Bay State.

[POWER SHIFT THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Massachusetts recently teamed up with seven other states to promote the use of electric cars, by developing compatible systems of charging stations and financial incentives. The deal also calls for the states to help the public sector incorporate EVs into their fleets. Electric car sales have been increasing, but the numbers are still tiny. So to get EV's into the mainstream faster than the federal fuel standard rules require, California, Connecticut, Maryland, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island and Vermont are joining Massachusetts in this effort. Ken Kimmel is the commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection.

Massachusetts Environmental Protection Commissioner Ken Kimmell says his next car is going to be an EV, and he wants to be part of a crowd. (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

KIMMEL: I think one of the lessons of environmental politics of the last number of years is that the states are way ahead of the federal government, and we’ve seen that, for example, in the regional greenhouse gas emission cap and trading where eight or nine states have cut emissions from power plants by about 50 percent, from 2005 to 2020, and we’re seeing again an interest in states leading the way as sort of laboratories of democracy. And I think that when states do this, they create a critical mass, and a tipping point where change is possible, where it gets made at the federal level or simply because of a percentage of the economy that we encompass, the auto manufacturers will comply with our demands because there’s so many of us and it will ultimately give them a signal that they should do on a national level. So that’s why these states all got together to do this, because there’s strength in numbers.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the numbers involved here.

KIMMEL: Sure. So among the eight states that we’re talking about, we’d estimate that there are, right now, about under 100,000 EVs out there on the road. That needs to ramp up to 3.3 million vehicles by 2025. In Massachusetts, similarly we have we estimate about 2,000 zero emission vehicles on the road right now, that needs to ramp up to 300,000 by 2025.

CURWOOD: So, you’re talking about a big increase. What will be the climate impact of that do you think?

KIMMEL: It’ll be dramatic. We wlll gain very significant reductions in our emissions from the transportation sector, and it’s hard to calculate it and give you the exact number, but it will make a big difference, and it also aligns very well with the President’s Executive Order, or agreement that was signed with the auto manufacturers, to raise mileage standards from about 25 miles per gallon where they are now, to over 50 by 2025. The electric vehicles will be a key element of that larger national goal.

An electric vehicle charging (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: So how does Massachusetts do its part?

KIMMEL: So there’s a lot of things that we are doing and need to continue to do. One is to deal with the fact that, currently, although this will change, the upfront cost of an electric vehicle is considered higher than the conventional car, and although you get a payback over the course of the vehicle because you’re saving a lot of money on fuel costs, for some consumers that’s an issue. There is a federal tax credit that addresses that, and we’re also looking, as we committed to do with the other states at other financial incentives that we can do to make cars more attractive.

CURWOOD: For instance?

KIMMEL: You know, potentially, differentials in sales tax based on people who buy EVs, grants and loan programs. One program that we just started which is very attractive is we’re giving a subsidy to municipalities who buy electric vehicles, and we’re paying a good part of the cost differential between the electric vehicle and the conventional one to encourage munis to buy these cars.

We’re going to do the same thing for public universities, and we’re also throwing in funding for charging stations. And the concept is that if you go to city hall, you’re going to see electric vehicles parked there with a charging station. You’re going to see that these work and people use them and will help to make them more attractive. The other thing that we can do, and we’ve agreed to do as part of the MOU is to look at some non-monetary benefits. So, for example, the possibility of electric vehicles being able to ride in high occupancy vehicle lanes, reserved parking or free parking for vehicles.

CURWOOD: Free parking?

KIMMEL: Free or reduced rate parking. That’s definitely one of the tools.

CURWOOD: Now what about the question of road signs and charging networks to get some compatibility here?

KIMMEL: I think that’s key. I think this needs a lot of branding and easy visibility for consumers. We need to overcome the thing, the phenomenon called range anxiety and the fears people have that if they’re taking a trip there won’t be a network of charging stations, and they’ll get stranded. So a really thoughtful network of charging stations with signage, with Smartphone apps that tell you where to go to get the car charged is going to be critical, and that is clearly one of the things that we’re going to work on collectively to overcome.

CURWOOD: To what extent is this consortium of states going to look at using electric car batteries to buffer the grid? There’s been research done, particularly at the University of Delaware that shows that if the grid has access to car batteries, at times it can really reduce costs for the grid and actually the car owners can get payments.

KIMMEL: I think that is really one of the most exciting ideas, to think about electric vehicles in the context of smart grids, and the idea that you could charge up your vehicle late at night when the price of electricity is very very low and get a benefit that way, and then if there are certain peak periods where there’s problems with the grid as a whole, this whole network of cars could send energy back into the grid when it’s most needed. This would be great for the consumers. It would again provide a significant financial advantage to them but also it could be massive energy storage network that could help us deal with those occasional reliability problems and blackouts. Syncing up the grid with electric vehicles and thinking about electric vehicles not just as transportation mechanisms but potentially stores of energy for the whole network is a great idea.

CURWOOD: So overall, what do you see as the future for electric vehicles in your state, Massachusetts?

KIMMEL: I think the future’s bright. I think we’re really well poised to take advantage of this, we have a good mix of government policies that will drive it. We have people who are receptive to electric vehicles. We certainly have firms that are engaged in battery research and the underlying science so there will be economic benefits to Massachusetts if these technologies take off, and I think it’s a matter of patient, persistent education and outreach, and creating the infrastructure to allow people to take advantage of these new technologies. So I think the future’s quite bright.

CURWOOD: Ken Kimmel is the Commissioner of the Department of Environmental Protection in Massachusetts. Thank you, Sir.

KIMMEL: Thank you very much. It was my pleasure.

Related links:

- Read the EV Memorandum of Understanding

- Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection

[MUSIC: Lou Reed “Sweet Jane” from Rock And Roll Animal (RCA Records 1974) R.I.P. Lou Reed 03/03/1942 – 10/27/2013)]

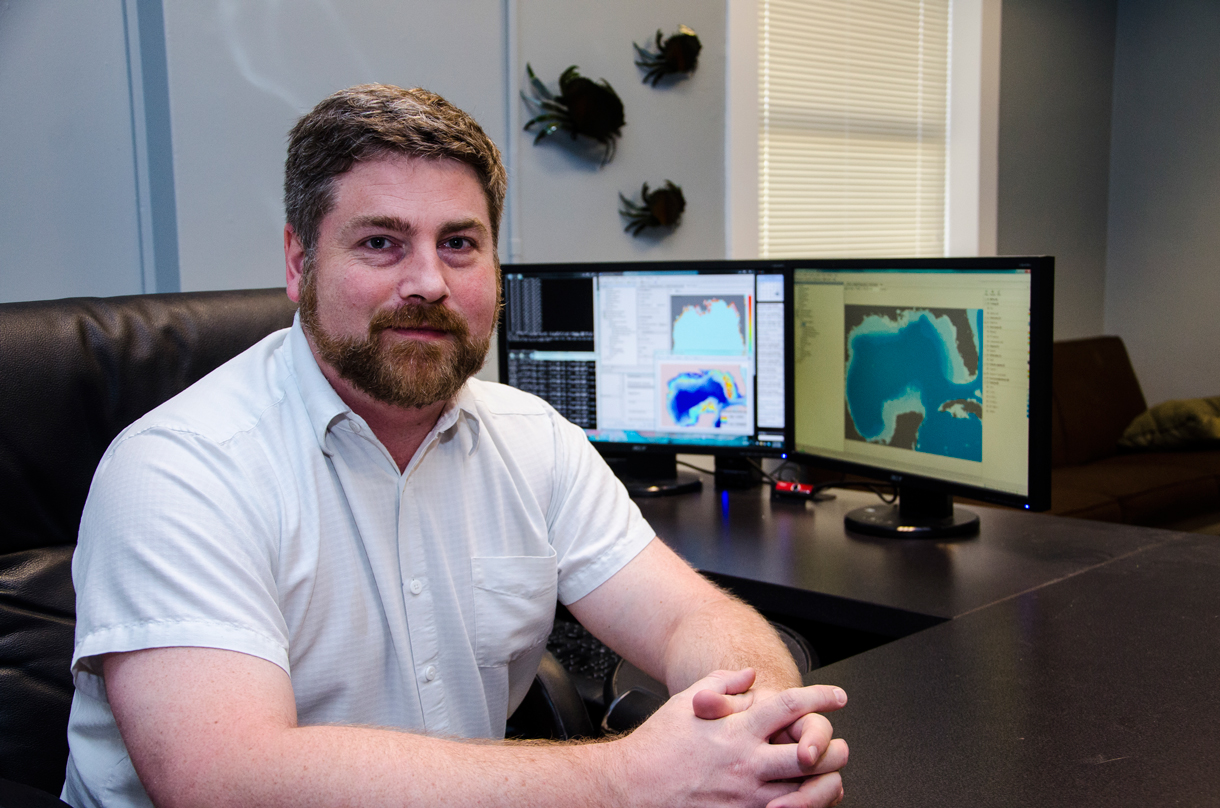

Gulf of Mexico Ocean Health Update

PhD student Michelle Masi from the University of South Florida displays some of the data she's gathered on fish stomach contents. By examining the last meal of fish brought in by other researchers, she's helping provide valuable information on who's eating who in the Gulf of Mexico—a necessary step for creating an ecosystem model. (photo: David Levin)

CURWOOD: Testimony in the multibillion dollar civil damage trial of the 2010 BP Gulf Oil spill recently wrapped up, and US District Judge Carl Barbier is now taking written post-trial briefs before the final penalty phase. That will determine exactly how much BP and its drilling partners must pay in damages under the Clean Water Act.

At the same time scientists continue to assess how the ecosystems of the Gulf are functioning, how they're recovering, and how they might best be protected from another spill. This is an enormous task for researchers. Some are biologists, but there's also a vital role for mathematicians and computer specialists at the Center for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of the Gulf Ecosystem, or C-IMAGE, as reporter David Levin discovered.

LEVIN: It’s been more than three years since the Deepwater Horizon spill hit the Gulf of Mexico, dumping more than 5 million barrels of oil into the ocean. Since then, researchers have been unraveling the impact it’s had on the Gulf as a whole, how the oil moved in the water, how that oil degraded, and how it affected marine animals along the way. But every spill is different, and studying one doesn’t guarantee that scientists can tell how the next one will play out. According to Jason Lenes, predicting that involves serious math.

LENES: You don't truly understand something unless you can describe it mathematically. What we try to do is use math to describe ecosystems and biology.

LEVIN: Lenes is a researcher at the University of South Florida. He’s one of a small group of people using complex equations to build a computer model of the Gulf - a kind of digital reproduction of the entire Gulf ecosystem.

Inside that virtual world, they’ll be able simulate future oil spills, and anticipate how they’ll affect fish and other organisms. But getting the model to work – well, that’s the hard part.

LENES: It's such a large picture, and there's so many questions, in terms of just the ecology itself, let alone the physics. It’s so much information.

Ecological Modeler Jason Lenes studies the fate of tiny creatures in the Gulf of Mexico, like plankton and algae. Based on data collected in the field, he's creating a detailed computer model of their life cycle. (photo: Courtesy Aimee Blodgett / USF)

LEVIN: First, the scientists need data on all the key species in the Gulf, from tiny plankton to huge whales. They have to know roughly how many are out there, where they live, how often they reproduce, how quickly they grow, and most importantly, what they eat. Without understanding the food chain, or who eats who, it’s almost impossible to build an ecosystem model.

AINSWORTH: If you want to make predictions about predators, about fisheries, about recovery time, that information on the food web is really not negotiable.

LEVIN: Cameron Ainsworth works with the modeling team at USF, and he’s trying to simulate the life cycle of fish in the Gulf. He says getting data on what they eat is actually pretty tricky. Most of the fish studies in the Gulf focus on commercial species, like red snapper or grouper, and there’s a lot less information on species fishermen can’t sell.

AINSWORTH: There’s no end to the holes. [Laughs] You know, just the nature of ecosystem modeling is that you’re bound to run into data deficiencies. And, you know, in a lot of cases those can’t be swept under the rug. Sometimes, he says, his team has to fill in the missing data themselves, by studying fish collected by other researchers.

AINSWORTH: What my laboratory did in particular was just survey the gut contents of fish. So we would take fish, bring it into the lab and then dissect it, and try to determine what the species has been eating…

Oceanographer Cameron Ainsworth from the University of South Florida. On the screen behind Ainsworth is Atlantis, a computer model that will ultimately offer a complete simulation of the Gulf of Mexico's Ecosystem. (photo: Courtesy Aimee Blodgett / USF)

LEVIN: For a group that works with computers most of the time, being elbow-deep in fish guts is kind of unusual. But it’s something that Michelle Masi does all the time. She’s Ainsworth’s PhD student. When the fish come in, she spends hours cutting open their stomachs and recording what’s inside.

MASI: So you'd look in there for anything that looks like it might be a little prey item. A claw perhaps, or some bones or scales. If there are scales in there, you know that it's eating fish.

LEVIN: But looking for scales and claws inside fish bellies can only tell you so much about who’s eating who. To build an accurate model of the Gulf ecosystem, you also have to factor in the tiny stuff, like plankton and bacteria. That's where Jason Lenes comes in.

LENES: The stuff that we're trying to model are at the base of the food chain. We're interested in the bacteria, we’re interested in algae, we're interested in the zooplankton, which are the little guys that eat the algae. So we want to see what is the baseline, what is the standard that goes on in the Gulf, and then when you add oil, how that would impact the algae and the zooplankton.

LEVIN: It’s a big job. For every one fish in the Gulf, there are huge numbers of those little critters. And they’re growing, reproducing, and being eaten every minute of every day, so the population can change dramatically in a short time. To keep track of that many organisms, the model Lenes is creating needs some heavy computer power.

Running a computer model of an entire ecosystem involves millions of calculations, and terabytes of data. In order to process that much information, the USF team turns to this high-powered computing center, which uses huge racks of processors to crunch numbers around the clock. (photo: Courtesy Brian Lindblom)

[FOOTSTEPS IN HALLWAY, DOOR OPENS]

SMITH: Hi, Dave,

LEVIN: Hey, nice to meet you.

SMITH: Good to meet you. So we're going up to the third floor where the data center is at...

LEVIN: Brian Smith oversees the University of South Florida's research computing center, the place where Lenes runs his models. He leads me into a squat brick office building, through a maze of cubicles, to a glass security door.

[SWIPE CARD BEEPS, DOOR OPENS, WHOOSH OF FAN]

LEVIN: Inside is the heart of the system. It’s a huge white room filled with racks of powerful computers. The fan noise is deafening.

SMITH: It's high performance computing. Lots of processors, lots of memory, very fast network. So we can actually take one simulation and run it on all these machines simultaneously in order to harness all of their power.

LEVIN: Even with all that computing power, the millions of calculations that Jason Lenes needs for his model can still take up to a week to run. And that’s just his latest version, which covers only a small fraction of the Gulf.

At the moment, he’s working on expanding and perfecting the model. Next, he plans to combine it with Ainsworth’s fish model, and together, they’ll create a simulation of life in the Gulf that covers everything—from the tiniest microbe to the biggest whale.

AINSWORTH: Yeah, that’s our hope.

LEVIN: Again, Cameron Ainsworth. He says that once the full ecosystem model is up and running, it’ll be incredibly useful for studying future spills, and testing how they might affect marine life.

AINSWORTH: For a given level of oil concentration, how do we expect fish to be impacted? What’s the impact on growth, on longevity, on their ability to reproduce and things like that. So I think what we hope to get is a little bit of a better perspective on what to do in the case of the next oil spill which is surely coming.

LEVIN: In other words, with more than eight thousand oil wells in the Gulf, it’s only a matter of time until another disaster. In the past, scientists have had to react to those spills after they happen, but using these models, they might be able to predict how they’ll play out ahead of time. They’ll know which fishing grounds should close first, which species will be hardest hit, and ultimately, what the impact will be on people in the Gulf.

For Living on Earth, I’m David Levin in Tampa, FL.

CURWOOD: David's story comes to us from Mind Open Media. To learn more, dive into our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- USF College of Marine Science homepage

- Center for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of the Gulf Ecosystem (C-IMAGE)

- USF Fisheries and Ecosystems Ecology Lab (Cameron Ainsworth's Lab)

- Collaboration for Prediction of Red Tides (Jason Lenes' Lab)

- USF Research Computing Center

[MUSIC: Monty Alexander “Three Little Birds” from Concrete Jungle: The Music Of Bob Marley (Telarc Records 2006) Congratulations Boston Red Sox!]

Jim's Bees

Workers with queen bee (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: When it comes to be time to change the time, and push the hands of the clock back, it's a harbinger of longer nights, and for those of us in northern hemisphere, of the wintry weather to come. But even as the days grow short and cold, writer Mark Seth Lender recalls a memory of summer warmth and risky sweetness.

LENDER: Jim Clinton is a large man, raw hands, sunburned brow, and he walks with the gait of gantry crane as he lumbers across that field over there. White boxes line the furrowed rows. They hold his heart: And the beat of ten thousand wings unfolds.

Workers with a queen bee (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

“Bend low,” he says, “you can smell a healthy hive.”

Mark Seth Lender inhales the scent of a healthy hive (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

I lean down, inches from the open combs, close my eyes and inhale through my nose. The smell is soft, spiced, mildly sweet; but the thing that compels is that idling purr that can turn on a dime to an angry roar - the sound of the sound of a hard demise.

Workers with queen bee (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The venom of bees breaks down the cells. The heart will race. The pressure falls. Blood thins beyond tolerance; breathing quickens, then drops to a trough. You will try to run, the mind confused you run the wrong way. And panicked stumble in your pain. Eyelids. Wrists. Fingers, both hands. The cheeks, oh yes and into the hair and beneath the clothes and if you scream? The tongue. Like a cobra’s hood they rise, a black strike in the warm of summer air… You lie on the ground, and die, right there.

All this they can, yet they do not. They are calm. An enormous orchestra tuning its strings, and a chatter like shaken seeds in an empty gourd as the gatherers tell of the pollen they’ve found. Where it lies. How far. While the workers come and go and antennae touch like fingertips and the small red tongues dart and kiss.

But now Jim Clinton opens the lid of another hive, “they’re angry” he says. “You better stand clear.”

And I do, but not near fast enough.

Thap!

Bee hits the side of my head the blow as hard as a finger snap then another and again now the nape of my neck and I know what they mean:

ARE YOU DEAF? MOVE BACK! MOVE BACK!

-2.jpg)

Jim Clinton smoking angry bees (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

So I do.

They pursue – 40 yards, no further - and mad as they are, not one stings…

It’s winter now. The bees are few, and small. The hum is gone. And the hive makes its sleeping sound: dry leaves scattered on hardened ground.

CURWOOD: Mark Seth Lender is the author of Salt Marsh Dairy: A Year on the Connecticut coast. For some photos of the beehives, buzz on over to our website, LOE.org.

[MUSIC: Marc Johnson/Eliane Elias “Foujita” from Swept Away (ECM Records 2012)]

CURWOOD: Coming up, what to do with a man about to be without a country thanks to climate change. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Frank Wess: “Low Life” from Jazz For Playboys (Savoy Records 1992 reissue)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Sharks and Coral - Science Note

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. In a minute, the rich and diverse coral islands and atolls of the Pacific Ocean are a haven for myriad species, but they may not last to protect all the people who call them home. First here's Andrew Keys with this week's note on emerging science, which also deals with coral.

KEYS: Coral reefs are under threat from climate change and ocean acidification, and now new research suggests that their future may rest in the jaws of some of their largest inhabitants. Scientists have discovered that fewer sharks correlate directly with failing communities of coral.

Shark populations are in steep decline worldwide, mainly due to demand for their fins. Scientists consider sharks a keystone species in the food web of coral reefs—that means if sharks are removed, the reef ecosystem could collapse.

Now researchers in Australia have found that overfishing of reef sharks has a cascade effect. Without the sharks, mid-level predators like snapper increase. Snapper, in turn, eat smaller fish that eat algae, and since algae compete with coral for reef real estate, fewer algae eaters mean less room for coral, and make it difficult for damaged reefs to recover.

But the scientists report some good news as well. Individual sharks stake out specific territory on reefs. So protecting sharks, even within limited areas, could go a long way toward protecting and rebuilding reefs.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Andrew Keys.

Related link:

Overfishing of Sharks Is Harming Coral Reefs, Study Suggests (Science Daily)

South Pacific Climate Refugee Goes to Court

Flooding in Bangladesh (photo: U.S. Marine Corps/Staff Sgt. Julius Hawkins)

CURWOOD: Recently a man from the Pacific Island nation of Kiribati made history. Ione Teitiota became the first person to ask a court to grant refugee status on the basis of climate change. He told the High Court in New Zealand that his family would suffer serious harm if they were forced to return to their low-lying homeland, as sea level rise is projected make life there untenable. Susan Martin is director of the Center for International Migration at Georgetown University. Professor Martin says the Teitiota case raises key ethical and legal issues about how the global community should deal with people forced to flee their homes in the face of climate disruption.

Flag of Kiribati

MARTIN: What he's arguing is that because of climate change he is the recipient of passive persecution and will be harmed if he returns home, because climate change is posing very severe dangers and damages on the population of his island.

CURWOOD: Now how unique is his claim?

MARTIN: Well, I think it’s quite unique, and I think it’s a stretch. Refugee policy is designed around protecting people where people have been persecuted or have a fear of future persecution because of their race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. The whole concept came about after Nazi Europe as a way of responding in the future to cases where people might face very very severe harm as a result of a protected characteristic such as religion or race as that was the case in Germany. The concept of passive persecution because of changes in the climate is a long distance from that original concept which pretty much still governs the asylum policies in most countries.

CURWOOD: Of course, at the end of the day, though, if the seas keep rising, as they’re projected to, Kirabati won’t be there. He surely will be a refugee, and he surely, if he went home, he’d be in danger.

MARTIN: Well, I think that the problem, even with that construct, is that people on the islands will not be endangered because of their race, religion, nationality, etc. He does raise though in the case, and the case raises a very very serious problem that still needs to be addressed, and that’s what do we do as a world to protect those who are going to be harmed as a result of climate change. And there will be people, not just those on the islands in the Pacific who will not be able to remain and live decent lives because of the impacts of climate change. Right now there are no policies to address that.

CURWOOD: So what do you expect the New Zealand court to do with his application at this point?

Increased flooding in Bangladesh due to climate change could make the country unlivable for millions of people (photo: Raiyan Kamal)

MARTIN: Well, I expect that they’ll likely reject it, that it doesn’t meet the refugee definition. I expect that there will probably be some passages in the decision that calls out for political and policy changes to address the situation that he’s in. I think what we need is a parallel legal regime that will provide assistance and protection to people who are losing their habitats, their livelihoods and potentially their lives as a result of climate change. So not to change the refugee definition but to have a second set of policies that are more specifically geared towards the situation of climate change.

CURWOOD: Where else might we see migration issues like this in the near future do you think, Professor?

MARTIN: Well I think we’re going to see it all over the world. I think there’s a number of different ways in which climate change may affect movements of people. Rising sea levels is probably the most talked about right now because it has the prospect of entire countries disappearing. The place that I think a lot of people are really worried about is Bangladesh. It’s a very crowded country. It’s a very poor country, and it will be seeing a lot of different effects of climate change, some of it already seen in the form of more frequent storms and more intense storms, but also year to year flooding. I think we’ll also see a number of places in which climate change will lead to more frequent and more intense droughts. There’ll be areas where it’s very unlikely that people will be able to continue to farm unless there are major advances in terms of drought-resistant seeds and other new farming techniques.

CURWOOD: Professor Martin, how well set is the international refugee system to deal with the question of climate right now?

MARTIN: It’s struggling. We have an established system for dealing with people displaced from conflict, but a very new, pretty fragile system for addressing people who are leaving as a result of environmental change, manmade disasters such as nuclear accidents, anything that creates dangerous situations for people, but doesn’t fit the refugee definition.

CURWOOD: When might this turn kind of cranky? I mean, one could see that someone could approach a country and say, “Look, your country sent all this carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, you’re part of the problem here. You need to give me a home.”

MARTIN: Well, we’re already seeing some of that rhetoric, and I think it’s understandable that the countries that are going to be suffering the most are not the countries that have caused the emissions for the most part. I think it’s now being much more diverted into saying that there needs to be financial support for adaptation and continued commitment to mitigating the impacts of climate change, and so I think that the governments of the countries that are the most effected are looking for the help of the international community, and the wealthier countries that have produced the impacts of climate change to help them to be able to help their own populations. I think that the next step along the way will be looking at how migration can be part of that adaptation strategy. We’ve tended to look at migration as a problem, something to be avoided, but in fact, migration has always been one of the principal ways that people adapt to the changing environment, and so we have to start to think about the positive ways in which migration can be a solution for thousands of people who may otherwise may not be able to fare very well as a result of climate change.

CURWOOD: Professor Susan Martin is Director of the Center for International Migration at Georgetown University. Thanks for taking the time.

MARTIN: You're welcome, I enjoyed it.

Related links:

- Susan Martin’s page at Georgetown

- Climate office of the Kiribati government

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell “A Beautiful View” from Big Sur (Okeh Jazz 2013)]

Beyond the Headlines

Salt water intrusion could harm agriculture and drinking water along the coast of Bangladesh (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: And now we turn to Peter Dykstra, publisher of the Daily Climate and Environmental Health News, for a new feature on Living on Earth that notes a few stories from beyond the headlines. Every day Peter and his crew comb the internet for stories of environmental change from around the planet, everything from the weird and wacky to little-noticed ones that we should watch out for as they emerge over time. He’s on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter!

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve!

CURWOOD: So what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: We’re going to go to two different parts of the world and we start in the tropics. EHN picked up a story this past week that might not seem like a whole lot right now, but we think it’s going to be a big deal for the world in the years to come. It’s from the capital city of Bangladesh, Dhaka, and the English language paper there, the Dhaka Tribune. They reported that salt water intrusion is becoming what they call, what scientists call, an alarming problem along the coast of Bangladesh.

CURWOOD: OK. So how does salt water get into fresh water?

DYKSTRA: The farmers and cities in the very densely populated country of Bangladesh depend in large part on groundwater in aquifers, drilling wells to water farms and to provide drinking water. There’s been so much pressure on the wells nearest the surface that water’s drawn out of them and salt water is essentially sucked in, and when you have sea level rise, that makes that whole problem worse. Eventually, the scientists say, there will be a huge problem along the coast of Bangladesh involving tens of millions of people in farms and cities with salt water intrusion making some of their drinking sources completely off limits, and that may be the good news.

CURWOOD: You’re calling that good news?

DYKSTRA: Relatively speaking, because the bad news is that Bangladesh’s other primary source of water is melting glaciers from the Himalayas, and the glaciers are definitely melting, but they’re melting a little bit too fast. If the glacier water goes away, and the coastal aquifers are put off limits and polluted by salt water intrusion, then you have a nation of 150 million very thirsty, very hungry, potentially very angry people, and that’s why a lot of folks are looking at water issues and climate change issues as global security issues.

CURWOOD: OK. Now where else are you going to take us on the globe?

Greenland is increasingly the site of rare-earth mining (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

DYKSTRA: We’re going to go to a very different place up in the Artic up in the cold weather, where the parliament of Greenland by one vote just decided to open up mining for uranium and for what are called ‘rare earths’, some of the strategic metals that are used in everything from windmill blades to electronics to the phone and recording equipment we’re speaking to each other right now. The reason that that mining industry is opening up in Greenland - they’ve known for a long time there’s a lot of money and a lot of minerals beneath the surface of Greenland - but the surface of Greenland has been beneath a lot of ice. The ice is leaving. The minerals are exposed. Multinationals, particularly from China and Australia, are looking to come in. It will change Greenland. It will enrich some people there. It will change the lives of just about everyone there, and this is all happening because that land-based ice in Greenland is melting and contributing to sea level rise which will also, as the Artic melts, the sea-based ice opens up, and shipping those minerals out will also become easier.

CURWOOD: And of course, the land ice melting raises sea levels…

DYKSTRA: Which brings us back to Bangladesh and a lot of low-lying places that are going to be imperiled by sea level rise.

CURWOOD: Hey, Peter, anything else before you go?

DYKSTRA: We’re just looking at sort of an ironic and sad twist...just about everyone knows this is the one year anniversary of superstorm Sandy and all the destruction that it caused in New Jersey and New York. But 24 years ago this month, the governor of New Jersey, back in 1989, Thomas Kean, a Republican, issued a very stark warning in an executive order about climate change and said that the coast of the New Jersey area, the Jersey shore, needs to be ready for severe storms and hurricanes that are going to be worsened as climate change becomes a reality. This is 24 years ago from a governor, a Republican governor. He may be eligible for what I like to call the Nobel prize in “I told you so”, and the problem is very few people listened, and if they had listened, the damage from Sandy a year ago might have been a little bit less.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra, Environmental Health News and the Daily Climate. Thanks! We’ll talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: Thank you.

[MUSIC: Steve Cropper “Help me Somebody” from Dedicated- A Salute to the 5 Royals (Stax Records 2011)]

CURWOOD: Next week on Living on Earth...trying to leap the hurdles that stand in the way of going solar in leafy Massachusetts.

MAN: I spent many hours, many days making sure that it would be suitable for solar. What I didn't take into account was that trees grow.

CURWOOD: But trees aren't the only obstacles. There can be red tape as well. That's next time on Living on Earth.

Related link:

Peter Dykstra is the head editor of the Environmental Health News and the Daily Climate

EARTH EAR WILD SANCTUARY -- WHALES WOLVES AND EAGLES OF GLACIER BAY

[SOUNDTRACK: Earth Ear: Bernie Krause Whales, Wolves, & Eagles of Glacier Bay from Wild Sanctuary: An Adventure in Sound (North Sound Records 1994)]

[WHALE SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week at the sea in Alaska's Glacier Bay…

[WHALE SOUNDS]

Hump-back whales are feeding and calling…

[WHALE SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: And nearby a harbor porpoise chimes in…

[PORPOISE CALLS]

As well as a pod of orcas…

[WHALE SOUNDS]

And the rumble of a huge chunk of ice breaking off a glacier and causing large waves….

[WAVE SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Bernie Krauss recorded this soundscape for his CD, Wild Sanctuary, Whales, Wolves and Eagles of Glacier Bay.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Andrew Keys, Helen Palmer, Kathryn Rodway, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Gwen Stevenson, Bill McKibben, Mark Hertsgaard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth