November 29, 2013

Air Date: November 29, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

REDD Agreement Reached in Warsaw

View the page for this story

This year’s UN climate negotiations in Warsaw featured a hunger strike and a walk out. But Tropical Forest expert Steve Schwartzman tells host Steve Curwood that in the final hour the delegates emerged with a concrete plan to limit emissions from deforestation. (05:30)

Just 90 Firms Have Tipped the Climate

View the page for this story

A recent study published in the journal Climactic Change found that the number of state and investor-owned operations responsible for the human impact on global warming may be smaller then you might think. The research shows that just 90 entities produced the majority of fossil fuel-related greenhouse gas emissions since the industrial revolution. (06:50)

Beyond the Headlines

View the page for this story

In our weekly segment, Beyond the Headlines, host Steve Curwood checks in with Peter Dykstra of the Daily Climate and Environmental Health News. This week we hear about climate scientists being offered free legal advice to deal with potential attacks on their research. (04:40)

Modern Gleaning Helps the Hungry

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Gleaning is an ancient tradition. In the Torah and Old Testament farmers are instructed to leave some food in their fields for the poor to collect. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports that modern volunteer gleaners can go to farmers’ fields at the end of the season to harvest the last of the bounty and then deliver the produce to food pantries for the food insecure. (10:00)

Bird Note ®: Atlantic Puffin

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Atlantic Puffins disappeared from Maine’s Muscongus Bay for more than 100 years when researchers reintroduced six chicks. They were expected to return to the spot where they fledged but scientists found they needed a little coaxing from an unexpected source- puffin decoys. Mary McCann reports. (02:00)

How Dogs Love Us

View the page for this story

Using brain scans from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Greg Berns attempted to discover if dogs really do love us. He joins our host Steve Curwood to discuss his recent discovers and insights into the relationship between canine and human. (13:15)

Small Matters

/ Ari DanielView the page for this story

Reporter Ari Daniel takes a look at how various organisms, from birds to water molecules, align themselves in seemingly random ways. (05:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Steve Schwartzman, Richard Heede, Peter Dykstra, Gregory Berns,

Reporters: Bobby Bascomb, Mary McCann, Ari Daniel,

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. New analysis calculates that just 90 companies have created nearly two-thirds of all human-generated greenhouse gases since the industrial revolution.

HEEDE: You can fit the presidents of these entities onto two greyhound busses. We have to get their help in solving the problem, as opposed to just being passive and profitable bystanders to continued climate destabilization.

CURWOOD: Also, a trip to a community farm to help glean the last of the fall harvest to give to hungry people.

NAVARRO: I love the gleaners. OK, they come and bring the fresh vegetables from their garden, and I give them out here in the pantry to the community and everybody loves it. It’s real food from Mother Earth, from loving hands that planted it, and it’s going to fall real good in the stomach.

[LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: We'll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

REDD Agreement Reached in Warsaw

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood. One bright outcome from the recent UN Climate negotiations in Warsaw is final agreement on the rules to reduce emissions from the destruction and degradation of forests, known as REDD. The loss of tropical forests is a major part of human-induced global warming, and since 2007 negotiators have been hammering out a way to address the problem. Now there is what’s called the Warsaw Framework for REDD, and the next task is to work out broad funding. Here to tell us more is Steve Schwartzman, the Tropical Forest Director for the Environmental Defense Fund.

SCHWARTZMAN: Well, I think what the international climate negotiation needs most of all is the kind of thing that happened in Warsaw around forests. This is a case where poorer developing countries and emerging economies and richer developed countries agreed on concrete steps that are going to allow them to achieve emissions reductions in a way that works for everybody. That gets over this interminable back and forth about who goes first and who’s responsible, and it finds us a win-win solution that allows the world to move forward on an important aspect of fighting climate change.

CURWOOD: So remind us, exactly how does REDD work? What’s the basic concept here?

Deforestation in Borneo (photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

SCHWARTZMAN: The basic concept is that a tropical forest, country or a state, or a province that can reduce its overall deforestation below historical levels should be able to be compensated, either by public sector donors, by other countries, or eventually by carbon markets for making those reductions.

CURWOOD: So what exactly was decided in Warsaw when it comes to REDD?

SCHWARTZMAN: Well, the parties to the international climate negotiation decided on basic technical principles for countries to be able to be compensated for reducing their deforestation. So they decided what countries need to do to show that they’re monitoring and measuring and verifying their forests, their forest carbon stocks, and the emissions from those, and how to set reference levels, which is the basis for getting results-based compensation. They also agreed that results-based compensation is going to be calibrated in carbon. That’s really good because it means that when there’s robust enough carbon market to be able to accommodate reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, this will fit right in.

CURWOOD: How new is this?

SCHWARTZMAN: The principle has been around for a long time. There’s never been a real agreement on overarching guiding principles for what countries need to do in terms of monitoring and measurement and setting reference levels to allow this to go forward. Now there is.

Steve Schwartzman (photo: Environmental Defense Fund)

CURWOOD: How big of a deal is this in terms of emissions, do you think?

SCHWARTZMAN: Well, overall, land use change, including tropical deforestation and agriculture, account for about 30 percent of all the emissions annually. Just deforestation is probably around half of that. So that’s on the order of the emissions from all of the trains and cars and buses and trucks and airplanes in the world. So it’s right after burning fossil fuels as a source, so it’s a big deal.

CURWOOD: Now, where is the funding for this going to come from?

SCHWARTZMAN: Well, there’s already about $700 million a year that’s been approved by different donor governments to fund this kind of approach. I think ultimately we’re going to see carbon markets investing even more than that going forward.

CURWOOD: And where exactly does the money go? I know that some people are concerned that the local people who traditionally rely on forests for their livelihood aren’t really seeing the financial benefits from REDD, might not really see them.

SCHWARTZMAN: Well, since REDD is really only starting in a couple of places, nobody is really seeing the financial benefits yet. Ultimately, for this to work, landowners who have rights to deforest that they’re willing to forgo in exchange for compensation, as well as forest communities, like indigenous peoples who have always protected the forests, and governments who are doing a good responsible job of taking care of the forests, the states, all need to benefit.

CURWOOD: So what do you see as the challenges now for REDD as it goes forward from here?

SCHWARTZMAN: I think it is still a major challenge that so far there is no single compliance of regulated market that actually accepts credit for reducing deforestation. It’s very important that governments like Norway, Germany, UK and the US have committed public sector funding for these things, but we’ve seen in the past that counting on public sector funding over time for a large scale payment for ecosystem services program is typically pretty dicey.

CURWOOD: So, in other words, you’re looking for the private sector to get in here.

SCHWARTZMAN: Yes, ultimately here we need really serious private sector involvement to make REDD work.

CURWOOD: Steve Schwartzman is the Director of Tropical Forests Program at the Environmental Defense Fund. Thanks for taking the time today, Steve.

SCHWARTZMAN: Thank you, Steve.

Related link:

Check out Steve Schwartzman’s page at the Environmental Defense Fund

Just 90 Firms Have Tipped the Climate

Oil rigs in Los Angeles in 1896. The study looked at emissions all the way back to the 19th century (photo: unknown, public domain)

CURWOOD: As the recent UN negotiations remind us, solving the climate crisis has become a massive undertaking involving the whole world. But a new study shows that most of the global warming emissions that led to the present situation come from just 90 enterprises. Rick Heede of the Climate Accountability Institute in Colorado led a team that compiled the data that reveals just which entities supplied fossil fuels from the start of the Industrial Revolution to the present. He joins me now on the line. Welcome to Living on Earth.

HEEDE: It's my pleasure to be with you, Steve.

Standard Oil refinery in 1896 (photo: author unknown, public domain)

CURWOOD: So why did you do this project? What got you started with this research?

HEEDE: Well, because we wanted to, in a sense, trace most of humanity’s emissions of carbon dioxide and methane that come from industrial sources, such as fossil fuel consumption, back to the extracting entities that had started the whole process. So we looked at a threshold of eight million tons of carbon per year in a recent year for the major entities: oil, gas and coal producers, as well as cement producers, and looked back over their historical self-reported production so we could base it on their own reported data.

CURWOOD: Now all this research looks like it involved a massive amount of work. How were you able to do all of this?

HEEDE: Steve, I have colleagues at various universities: at Cambridge, at the British Library in London, in Sydney, in Johannesburg, Berkeley, to look at collections of annual reports housed in business libraries. Unfortunately, most of them aren’t catalogued so we had to go in person to dusty stacks and find the old reports for most of these investor-owned companies going back to the early 1900s, sometimes even earlier than that.

Gas flaring from a rig (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Tell me about your process and what it was like, and how did you account for emissions from the 1800s?

HEEDE: So we take their produced fuels, reported either in annual reports or in company histories and other sources, and we know how much carbon is in oil and gas fairly accurately. We also wanted to track how much carbon was in the coals, because that varies by heating value and coal rank, so we documented this as carefully as possible...what kind of fuel, where it was produced, so we can track the carbon from the fuels produced into what was actually combusted by consumers. And for that, we also had to deduct for non-energy uses of fossil fuels, particularly petroleum, that goes into petrochemicals and lubricants and wax because we wanted to deduct for the carbons stored in long lived products and just focus on tracing the emissions in the atmosphere back to the fuels produced.

CURWOOD: So after all this review, what exactly did you find?

Gas flaring from a rig (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

HEEDE: We found that for these 90 entities that we call carbon majors, 81 of which are investor or state owned corporations, that they have produced 63 percent of all the carbon emitted to the atmosphere since 1751, and we traced each fuel to each company.

CURWOOD: So how was that distributed throughout these 90 entities?

HEEDE: They were fairly evenly divided between the nine government-run industries; in Poland for example, in the coal industry, coal produced in China, so there you have nation-states in nine cases, former Soviet Union, for example, and we also have 31 state-owned oil and gas companies like Saudi Aramco and Pemex, and 50 investor owned companies such as Shell and BP and Eni and Total that we all know about.

CURWOOD: So who were the largest polluters?

HEEDE: The largest investor-owned and state-owned companies are Chevron and Exxon Mobil, followed by Gazprom and Saudi Aramco and Shell and BP, roughly in that order.

CURWOOD: And together they account for what percentage of overall emissions, would you say?

HEEDE: Well, if we take the top ten, they’re responsible for about 13 percent together. If we take all the investor-owned companies, they’re responsible for 22 percent of global emissions since 1751, and the largest of that is Chevron, and they’re at 3.5 percent.

CURWOOD: How many of these companies are still operating today?

HEEDE: Nearly all of them. We did trace some of the emissions back to companies whose assets upon dissolution, like British Coal, we weren’t able to trace to existing companies, but almost all of these companies are still in existence, in part because we tried to include mergers and acquisitions by the existing companies. So Chevron, for example, has merged with Texaco in the early 2000s. Texaco and Chevron absorbed Getty Oil and Gulf Oil, etcetera, so we tried to include previous companies that were merged or absorbed.

CURWOOD: What do you make of this finding? It seems like an awfully small number.

HEEDE: You can fit the directors and presidents of these entities onto two Greyhound busses. It’s a small number and it highlights that they’re just a few dozen individuals on boards of corporations that can make different choices in dealing with solving the climate. I think they can have a vast positive influence on how we deal with climate change. We have to seize the opportunity now to get their help in solving the problem as opposed to just being passive and profitable bystanders to continued climate destabilization. And I think shareholders will all notice which of these companies become leaders in the climate change arena and which become laggards, and we can choose between the two more wisely.

CURWOOD: In the end, what do you hope comes out of your research?

HEEDE: That we focus more attention on how to deal with existing proven reserves. We have three times as much in proven reserves as the atmosphere can afford to absorb to protect climate stability. And of course, international climate negotiations have a very positive role to play here, but so do producers who have the ear of politicians, as well as of their shareholders, and can influence how resources are produced and distributed and used. And we have a dataset now of 90 entities, what kind of fuels and emissions are traceable to them year by year, so it will be a useful way to devise a metric on how to reduce emissions in the future. Maybe there’s some obligation by the 90 carbon majors to reduce their emissions over time in concordance with their historic emissions in the past.

CURWOOD: Rick Heede is the Co-Director of the Climate Accountability Institute. Thanks for joining us, Rick.

HEEDE: Thanks. It was my pleasure, Steve.

Related links:

- Read Richard Heede’s paper here

- Check out this video visualization of emissions in 2010

- The Guardian’s visualization of the data

[MUSIC: Nguyen Le’ “Are You Experienced” from Purple: Celebrating Jimi Hendrix (ACT Music 2003) Happy Birthday Jimi 11/27/1942 – 09/18/1970)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...why some scientists might need lawyers. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chico Hamilton: “A Trip” from The Dealer (Verve Music Group 1966) (R.I.P. Chico Hamilton 09/20/1921 – 11/26/2013)]

Beyond the Headlines

Climate scientist Michael Mann filed deformation lawsuits after his e-mails were stolen and taken out of context by climate change deniers.(Photo: Michael Mann)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Time now, to check in with Peter Dykstra, publisher of the Daily Climate and Environmental Health News, for a few items from beyond the headlines. He joins us on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi there, Steve. We’re taking a look this week at climate science and when it collides with politics it can get ugly and it can get surreal. First, we’ll look at something that’s going on in North Carolina. The state last year, the state legislature, took a very bold step regarding sea level rise - they outlawed it.

CURWOOD: They outlawed it? It sounds like King Canute, the old Danish king commanding that the seas roll back.

DYKSTRA: Something like that, or parting the seas. The North Carolina Legislature has very broad and sweeping powers apparently, but in June of last year they voted to block the use of sea level rise data in coastal planning. That does a favor for coastal developers in keeping those sea level rise statistics out of the way in building in coastal towns and along the barrier beach. And of course, North Carolina’s got some beautiful beaches.

CURWOOD: Indeed.

DYKSTRA: This month, something else happened, the Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh , which is funded by the state, and run by state employees, rejected a documentary on sea level rise that some scientists and activists had hoped to show there.

Peter Dykstra is publisher of the Daily Climate and Environmental Health News. (Peter Dykstra)

CURWOOD: Ah ha, so are we looking at the makings of yet another science-versus-politics train wreck here?

DYKSTRA: Well, the museum director says there was no political interference, there was no pressure. The documentary, which is called Shored Up, has generally received good reviews – it’s run in theaters, it’s run in other museums, it’s being shown elsewhere in North Carolina in fact. But those activists and scientists are a little upset, and they say that they’re very surprised to see that sea level rise does not make the grade as a scientific issue for the state’s premier science museum.

CURWOOD: And speaking of scientists, out on the West Coast is one of the world’s great annual science meetings that’s coming up, and you’re going to tell us there’s something new and a little bit startling in it this year?

DYKSTRA: Well, every year in early December in San Francisco, there’s the spectacle of tens of thousands of earth and atmospheric scientists in their annual migration to the American Geophysical Union conference, probably about 20,000 people, maybe a little bit more that, will be there this year, and for the first time, there’s going to be some setup for scientists to get free legal advice.

CURWOOD: Peter, why would scientists need lawyers?

DYKSTRA: Most scientists don’t need a lawyer and hopefully they never will, but with climate science that’s just no longer the case. They’ve been sucked into a political vortex, they get accused of being money grubbing con-men when they go for grants to do their science, sometimes those accusations come from political operatives who make a lot more money than most climate scientists do. The scientists get their documents subpoenaed by the thousands - that’s a new form of harassment - and then there’s the case of Michael Mann. Mike’s a climate scientist who was on the receiving end of some absolutely unhinged accusations, and he’s turned them into a defamation lawsuit that’s working its way through the courts right now.

CURWOOD: Now Professor Mike Mann’s name also came up in another one of the most famous, or should I say, infamous science and politics meltdowns.

DYKSTRA: Four years ago this month the whole scientific community, particularly climate scientists, were knocked for a loop. Thousands of climate scientists’ emails were hacked, or maybe just stolen. This all took place at the University of East Anglia in Britain. Some of Mike Mann’s correspondence and emails were among them. And then somehow those emails, somehow, someway, found their way into the hands of climate skeptics and deniers - they turned them into a political attack. They made a big deal out of a few poorly chosen phrases and catty remarks. Yup, climate scientists can get catty on the web, just like the rest of us. All of this happened just before the Copenhagen climate conference. The scientists didn’t handle the response very well, but ultimately, there were multiple investigations and inquiries into all of this, and all of those inquiries concluded that climate scientists weren’t the venal and corrupt enterprise that climate deniers would have us believe.

CURWOOD: So I think stealing those emails is criminal. What happened to the people that did that?

DYKSTRA: The police treated it like a criminal case, they treated it like a theft. They never found the perpetrators, and it turned into a sort of a climate science crime story - and you thought all this science was dull.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is publisher of the Daily Climate and Environmental Health News. Thanks so much, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thanks, Steve. Talk to you soon.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News

- The Daily Climate

- Contact Peter Dykstra on Twitter

[MUSIC: Keith Jarrett “V1” from No End (ECM Records 2013)]

Modern Gleaning Helps the Hungry

Gleaning volunteers pick lettuce at Waltham Fields Community Farm. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Much of North America is now settling into the cold, dark time of year. Thanksgiving celebrated the bounty of the harvest, and the farmers’ markets have just about all shut down. But that doesn’t always mean that farmer’s fields are empty - in fact, a lot of perfectly good food often remains. Now thanks to the age-old but newly popular custom of gleaning, some of the fresh food that would otherwise be wasted is getting to some of the people who need it most. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb prepared this report, starting in a farm west of Boston.

CRAWFORD: Thanks guys for coming out today, we’re at Waltham Fields Community Farm. We are going to harvest some lettuce and maybe some collard greens as well.

Gleaning coordinator, Matt Crawford, demonstrates the best way to harvest lettuce. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Matt Crawford welcomes a group of five volunteers in the parking lot of a small farm, 10 miles west of Boston. They’ve come to glean - to collect the last of this year’s greens to donate to a food pantry produce that would otherwise go to waste.

[WALKING ON GRAVEL]

BASCOMB: Matt leads the gleaners out to the long furrowed fields. Most of them are empty now, rows of soil waiting for the spring planting. But four rows at the end are covered in a long white gauzy sheet.

Waltham Fields Community Farm. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[FABRIC PULLING SOUND]

BASCOMB: Matt pulls back the fabric to reveal perfect heads of red and green leaf lettuce. In the summer they would easily fetch two or three dollars apiece at the farmers’ market.

CRAWFORD: I’m sure most of you have harvested lettuce before, but I’ll show you the best way to do it. Carefully grab it, pull it back, tilt away from ground, from the earth. Cut it right at the base so leave any roots in ground. Prune off any dirty or dead looking leaves, anything that’s yellow, and we’ll put it right in the bag.

(Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BELL: There’s stuff besides lettuce. We’re just going for the lettuce?

CRAWFORD: Just the lettuce, yeah. All this other stuff is weeds, which are actually edible but we’re not going to eat them.

BASCOMB: Volunteer Bruce Bell gets to work at the top of the row, crouching down to cut the lettuce with a small sharp knife.

BELL: This is a beautiful one, a few dead leaves, some dirt, but more or less a beautiful head of lettuce. I’m a gardener also and I wish I could do things as good as this. I’m out here to admire everything that’s so beautiful even at this late season.

(Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[SOUNDS OF HARVESTING LETTUCE]

BELL: A few dead leaves here, brush them off and in we go.

BASCOMB (on tape): So, why do you do it? Why do you like coming out here?

Farmer Zana Porter (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BELL: I like the exercise, I like the fresh air. I like the connection it makes to other people that everyone should eat as well as I do and I eat pretty well and this is one way to help that along. You can see how much, I wouldn’t call it waste, but so much in the food chain that could go to waste if we weren’t doing this.

PORTER: I think the farmers have big hearts and don’t want to see food go to waste.

BASCOMB: Zana Porter is one of the farmers at Waltham Fields Community Farm. Porter says by this time of year they no longer have a market for the produce left in the fields.

Volunteers collect 576 pounds of lettuce into plastic bags. (Bobby Bascomb)

PORTER: At the end of the season we reach a point where our staff levels drop off, we’ve met the demands of our CSA and if it’s been a good season we still have food in the field that needs to go somewhere. So we call on the gleaners to come get the last of what’s out in the field so it doesn’t go to waste.

BASCOMB: This community farm is run as a non-profit and giving back to the community is part of their mission. But Porter says there are also practical reasons for getting as much as possible out of the fields.

The Food for Free van delivers recovered food to food pantries across Cambridge. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

PORTER: Sometimes it’s really important to clean out your fields. It’s important to get anything that might carry disease through the winter out of your fields. There’s a lot of insects that over- winter in certain crops. And if you leave that crop to rot there, that pest can over-winter, it’s going to be there again in the spring. I think there’s probably some motivation in that as well.

BASCOMB: Gleaning is an ancient tradition. It’s referred to in the Torah and the Bible. Leviticus chapter 19 instructs, “When you reap the harvest of your land, do not reap to the very edges of your field or gather the gleanings of your harvest. Do not go over your vineyard a second time or pick up the grapes that have fallen. Leave them for the poor and the alien.”

The food pantry in the basement of the Food for Free basement. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

Gleaning continued into the 19th century as a social safety net throughout much of Europe. Today there are gleaning organizations across much of Europe and the US. Duck Caldwell is Executive Director of the Boston Area Gleaners.

CALDWELL: This year we we’re going to recover over 70,000 pounds. That equals close to, when you convert it to four ounce servings, that’s 300,000 servings of fruit and vegetable.

BASCOMB: Caldwell says they pick at least 30 varieties of produce, all kinds of greens, eggplant, peaches, carrots, apples, turnips, squash… anything you might find in a farmers’ market can be gleaned when there’s a good harvest.

CALDWELL: We’re going to serve about 25 farms this year with our gleaning. There are well over 1,000 in this area. So the potential is huge. We’re doing a good job meeting the demand we’re getting currently from farmers, but the demand on the side where people actually need this food, there’s much more there, so there’s a lot of work to be done.

BASCOMB: After three hours of work the volunteers picked 576 pounds of lettuce. They pack the harvest into banana boxes and load them into a van for delivery. Roughly half of what’s gleaned goes to the non-profit, Food for Free, which distributes to 86 food banks from its headquarters in Cambridge. Sasha Purpura is the Executive Director.

PURPURA: Food for Free is an organization that essentially captures food that would otherwise go to waste, perfectly good healthy food, and distributes it into the emergency food system where it can reach those in need.

BASCOMB: Food for Free staff makes daily rounds to local grocery stores to collect good food that would be thrown away at the end of the day, but she says what the gleaners supply is special.

PURPURA: By far the gleaners’ food is without question the absolute best food we can get. It's the freshest, it’s local. The people who are receiving it love fresh vegetables as much as anybody else does.

BASCOMB: Purpura says it is relatively rare for food pantries to have access to fresh, local produce.

PURPURA: A lot of food pantries can get food from food banks but it’s typically shelf stable canned stuff. It’s very hard for small food pantries to carry produce because they don’t necessarily have the storage for it. They need it on the day that the pantry is opening, it’s volunteer run. And because the gleaners and Food for Free can deliver day of, it really allows them to offer more than canned sodium enhanced stuff.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: In the basement of the Food for Free office is a food pantry that serves hungry people in Cambridge. Sasha leads the way and introduces me to Aida Navarro, the food pantry manager.

PURPURA: Hi Aida.

AIDA: Hi, sweetheart. Are you the radio girl?

BASCOMB: I am. What gave it away? [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: Aida has a kind face and an affectionate manner.

NAVARRO: I love the gleaners. OK, they come and bring the fresh vegetables from their garden, and I give them out here in the pantry to the community and everybody loves it.

BASCOMB (on tape): Why do you think they love it?

NAVARRO: Because it’s real food from Mother Earth from loving hands that planted it and it’s going to fall real good in the stomach. [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: Freddy, the pantry’s food manager, stands amid boxes of produce and offers them to a small frail, elderly woman named Anne.

FREDDY: We have potatoes, onions, collard greens.

ANNE: Greens?

FREDDY: You want collard greens?

ANNE: Yeah. And lettuce? You have lettuce?

FREDDY: We have a spring mix or we have this….

ANNE: Spring mix. Terrific!

FREDDY: Green pepper?

ANNE: Sure. It’s very good things.

BASCOMB: Do you like the fresh produce, ma’am?

ANNE: Absolutely, it’s the best.

BASCOMB: Why is that?

ANNE: Well, it’s very expensive. It’s something hard to get. So, I like it very much.

FREDDY: Eggplant?

ANNE: Sure.

BASCOMB: What kind of things do you typically get this time of year?

ANNE: Anything green. It’s beautiful. What they do is so important for us. I get things I couldn’t afford. I get a lot of greens. It fills in spots I would otherwise neglect. And it’s a little gift. It makes people happy.

BASCOMB: Visitors to the food pantry are young and old, black, white, Hispanic, Asian and everything in between. Aida greats a familiar face.

AIDA: Come on, baby! We know.

BASCOMB: Rudolph West is a tall 63-year-old, missing most of his teeth, wearing an oversized trench coat. He says he’s never heard of the gleaners, but loves the idea.

WEST: I think it’s a beautiful thing. It’s charitable, someone’s taking the initiative to try to do something for others.

BASCOMB: West lives at the Y and says he doesn’t have access to cooking facilities so he can’t use the vegetables but he’s touched by the thought of the gleaners collecting food for the less fortunate.

WEST: It’s very helpful, and it’s good to be charitable, you know. Pay your tithes, that’s my motto. I’m a very religious person, which is a personal bond, but I hold things dearly in my heart and I shed tears over stuff like that. It shows how you can show piety like Jesus had. He was humble and submissive. That’s a good trait, a good characteristic, I like that.

BASCOMB: So a charitable tradition that dates back to before the time of Jesus is alive and well here in Massachusetts thanks to generous farmers and volunteers.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb at the Food for Free pantry in Cambridge.

Related links:

- Food for Free

- Boston Area Gleaners

[BIRD NOTE THEME]

Bird Note ®: Atlantic Puffin

An Atlantic Puffin coming in for a landing. (© Steve Garvie)

CURWOOD: Of all sea-birds, one of the most charming and funny must be the puffin, with its black and white plumage and its amazing bright beak. But Atlantic puffins had disappeared from some of their traditional range, until an enterprising scientist who loved the birds had an idea.

Here's Mary McCann with BirdNote®.

[WAVES BREAKING ON SHORE]

(Photo: Nature)

MCCANN: They had been gone from the island for a hundred years. But in 1973 Dr. Stephen Kress reintroduced six Atlantic Puffin chicks to Eastern Egg Rock, an island in Maine’s Muscongus Bay. He nurtured them by leaving fish in their underground burrows. A few weeks later, the birds fledged, departing at night for the open sea. Knowing puffins return to the spot where they fledge, he and his team waited. For four years, no puffins returned. Here’s Dr. Kress:

KRESS: So in 1977, I began trying to think more like a puffin. And I began to try to imagine what it must be like for a puffin that would head off to sea, come back, and find no other puffins at the island. And of course there hadn’t been any other puffins for 100 years, so what would this puffin think? Would it even take a chance about coming ashore? And I began to realize that normally a young puffin coming home would find other puffins. It would be attracted to them…perhaps interact with them, and become comfortable at that location. And I was concerned that maybe some of my puffins were coming back but not coming ashore, and that’s when I decided that I would try to put out some decoys.

An Atlantic Puffin (© Petur Gauti)

MCCANN: The decoys worked. Now the island, with much continuing work by Dr. Kress and Project Puffin, is home to more than 100 nesting pairs.

I’m Mary McCann

[CALLS OF ATLANTIC PUFFIN ADULT AND THE PIPING OF YOUNG]

CURWOOD: There are photos at our website, LOE.org.

[Interview by Todd & Chris Peterson

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Call (groan) of Atlantic Puffin adult with piping of young [62361] recorded in nest burrow by W.W.H. Gunn.

Wave action feature is Nature Essentials SFX #21 recorded by Gordon Hempton of QuietPlanet.com. Ambient waves recorded by C. Peterson at Hog Island, Maine.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2013 Tune In to Nature.org November 2013 Narrator: Mary McCann]

Related link:

Bird Note

[MUSIC: Rory Gallagher “I Can’t Believe It’s True” from Rory Gallagher (Eagle Rock Entertainment 2010 Reissue)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...searching for proof that the dog you love, really loves you back. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Cannonball Adderley: “Country Preacher” from Phenix (Fantasy Records 1975) Happy Birthday Nat Adderley (11/25/1931 – 01/02/2000)]

How Dogs Love Us

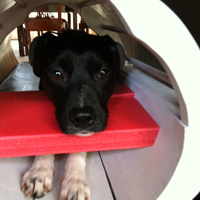

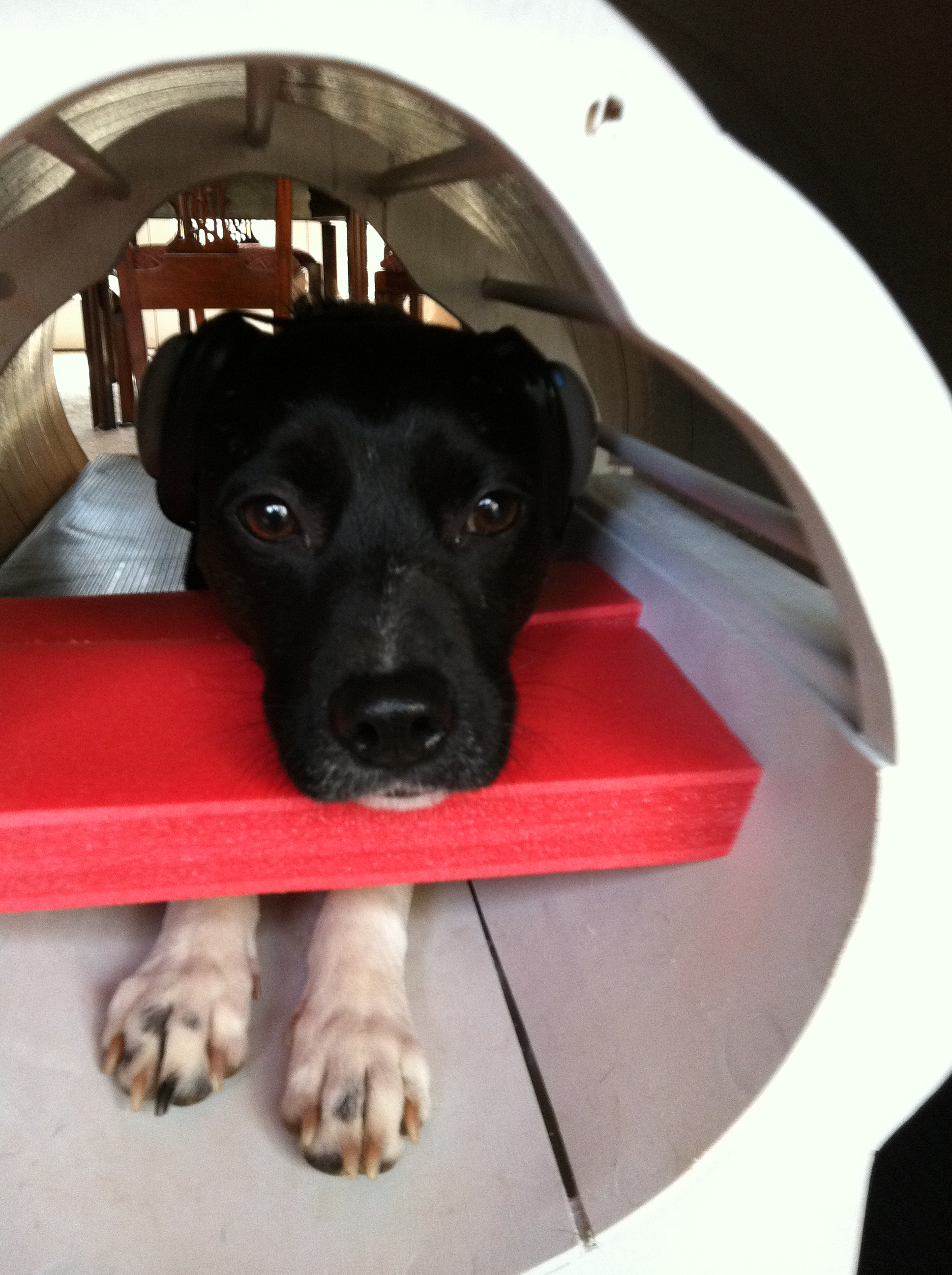

Callie, one of the first dogs to have their brain waves captured, waits in the MRI machine. (Greg Berns)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Most people who have a dog are sure their dog loves them—why else would their pooch seem so sad when they leave and be so tail-bangingly happy when they return? Now a researcher is using MRI brain scans to offer scientific proof that dogs indeed have emotions similar to those of humans. Professor Gregory Berns, a professor of neuro-economics at Emory University, recently wrote a book called How Dogs Love Us: A Neuroscientist and His Adopted Dog Decode the Canine Brain. Professor Berns joins me now from Atlanta, Georgia, but before we talk about dogs and their emotions, tell me, what exactly is a neuro-economist?

BERNS: A neuro-economist is someone, like me, who uses neuroscience technology to understand human decision-making.

-Bryan-Meltz.jpg)

Professor Gregory Berns is the leader of the team working to examine the canine brain. (Greg Berns)

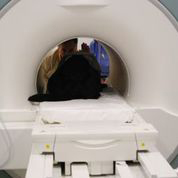

CURWOOD: How did you come up with the idea to study the canine brain using an MRI machine?

BERNS: Funny story - well, funny and sad story, I guess. It was a couple of years ago after one of my favorite dogs passed away - it was a pug, named Newton, and he lived to the ripe old age of almost 15 - and it was kind of remarkable after 15 years with such a dog you become pretty attached to them, and I think it got me wondering what Newton had been thinking all those years, and whether he had anything like the feelings that I had for him. Could we actually use the technology I had been using in humans and train it on the canine brain to try to understand how a dog’s mind works.

CURWOOD: So tell me, how are dog brains and human brains different?

BERNS: When you look at them, at first glance, there are some very obvious differences, and in fact, you don’t need an MRI to know that a dog’s brain is quite a bit smaller than a human brain. But in the world of neuroscience, brain size is not necessarily everything. So once you take size out of the equation, then the thing you notice is that the dog brain has a very large part of its brain devoted to smell, and we call it the olfactory bulb, and it’s kind of this projection that comes out in front of the brain that kind of sits above the nose of the dog.

Tigger, a Boston terrier, poses with brain scans. (Greg Berns)

Rosey, a Doberman, trains with owner Marci Soran with a mock version of an MRI. (Greg Berns)

Greg Berns works with one of the canines to examine response to hand signals. (Greg Berns)

Caylin, a sheep dog, trains in preparation for the sniff experiment. (Greg Berns)

A series of images of the canine brain. (Greg Berns)

Callie practices in preparation for the MRI machine. (Greg Berns)

Caylin gives Greg Berns a big kiss. (Greg Berns)

Pearl, a golden retriever, gives vet tech Rebeccah Hunter a big kiss. (Greg Berns)

Greg Berns gives Friday, a yellow lab, a big hug. (Greg Berns)

Now, humans have kind of tiny olfactory bulbs, in fact, you have to look really hard to find them on an MRI, but in a dog, it’s probably about 10 percent of the brain. Now that says what’s different, but there’s also a lot that’s in common. In fact, all mammalian brains have many structures in common, and when you look at certain parts of the brain like the brain stem, and parts of the brain called the limbic system, and the basal ganglia, these are pretty much common to all mammals and many non-mammals as well. And so that exists in a dog, just like humans.

CURWOOD: So now, this part of the brain is called the caudate region, and it’s common to dogs and to people.

BERNS: It’s common to dogs, people, monkeys, chimps, rats, every mammal has this part of the brain, and it basically serves a fundamental function of being a living, breathing animal, which is that you have to know what’s good and what’s bad, and approach those things that are good, and run away from those things that are not good. So in humans, when we do these experiments, you know, when we show people things like money, or they get money or food that they like, and you can ask them what they’re feeling, what kind of emotions are associated with that, almost always, it’s some kind of positive emotion.

CURWOOD: And, of course, you point to a basic problem - people tell you they like these things, but dogs, at least my dog, doesn’t really talk that precisely.

BERNS: Exactly, and that’s the whole reason we’re doing the fMRI on dogs. So the idea of the project then, is that by training the dogs to go in the scanner and holding still enough to do this, if we can show them things that they like that are similar, then we can use their brain activation as a kind of way to bridge between the dog and the human world.

CURWOOD: So tell me about the dogs in this experiment. You had your dog, Callie, and another dog, McKenzie. What were they like?

BERNS: So Callie is kind of terrier mix and the other dog, the initial two dogs, the other one was a border collie named McKenzie.

CURWOOD: So explain the two experiments that were used in this project for me?

BERNS: The original experiment was just to prove a concept because nobody thought this would work. So our first experiment was to prove that we could do this, and that we could get interpretable data from the dog’s brain. For that experiment, we trained the dogs on two hand signals, so one hand signal meant, you’re going to get a piece of hot dog, and another signal meant no hot dog. We purposely picked something that was easy that had a high chance of success, and because we knew about the caudate nucleus in humans, we also knew to look there in the dog brain. So the theory was that if the dogs were understanding hand signals, we should see activity in this part of the brain to the hand signal that means they’re going to get food.

CURWOOD: So these had to be really stinky hot dogs, right?

BERNS: Well, it’s funny you should bring that up because actually the earliest version of this experiment we did was, we actually had peas, like the vegetable, a pea and a hot dog because we thought, “well obviously the dogs are going to like the hot dogs more than peas”, and that experiment actually didn’t work. There was no difference in brain activity between peas and hot dogs, and we then realized after we did it that, the dogs actually didn’t care that much what they were eating - they just liked to eat the food.

CURWOOD: Professor, talk to us a little bit about the sniff experiment, how dogs tease out the difference between their owners and others, and other dogs for that matter.

BERNS: Sure, so one of our later experiments is getting away from hand signals and getting closer to what we think the dog’s primary sense is, which is smell. So one of the things we’ve done is present smells to the dogs while they’re in the scanner, and in the initial experiment we presented five smells - presented the scent of a familiar human in the household, a familiar dog in the household, and then we had unfamiliar people, unfamiliar dogs, and then we actually presented the dog’s own scent to them while they were in the scanner. So what we’ve seen now, and we’ve done this in 12 dogs, is that, again the same part of the brain, the caudate nucleus, seems to react exclusively in this experiment, to the scent of a familiar human, and that’s pretty remarkable because the scent of a human was obtained not from the person who is actually handling the dog in the scanner, but from someone else in the household. So that means that the dogs recognize that scent, and they have some memory for that person who’s not there physically, that are distant in time and space, and that it seems to be associated with a positive...we call it a positive emotional response.

CURWOOD: So, Professor, summarize for me the results you obtained and the work you describe in the book here.

BERNS: We’re kind of left with two big results, I would say, so the first is that we can demonstrate this positive response, first for hand signals, meaning hot dogs, but more importantly, with regards to smells, that it also transfers to the smell of people that the dog lives with. And this is important because kind of going into that we didn’t know whether the dog’s primary bond, if you will, in a household full of dogs and people would be with people or their fellow canine companions. You know, every other species out there bonds pretty much exclusively with what we call kind specifics, members of the same species. And now we’re seeing right here, with the brain data, that dogs seem, well at least dogs in our study seem, more bonded with the people in the household than the other dogs. This, to me, is incredibly important because it shows social flexibility of dogs in their ability to kind of bond to people, first and foremost.

CURWOOD: Professor, how does your dog project clarify the human-canine relationship, do you think?

BERNS: Well, we’re trying to understand the dog-human relationship from the dog’s perspective, and specifically, we are looking at brain responses in the dog, as the dog is interacting with a human. This is quite remarkable because now that we’ve done our initial experiments and proven that we can get quality data, now we’re doing much more sophisticated experiments and questions. So, for example, currently, right now, we’re trying to understand how the dog’s brain responds to these hand signals, whether it’s given by the owner, whether it’s given by a stranger, or even whether these signals are given by a computer. We’re already beginning to see differences in response of the caudate nucleus as well as other brain regions depending on who’s giving the signal.

CURWOOD: Professor, when the owner showed the hot dog sign versus the stranger showing the hot dog sign, what was the difference?

BERNS: So this is brand new work, so this is kind of just rolling right off the scanner this week. It varies by the dog. So some of our dogs seem to have essentially have caudate responses primarily, if not exclusively, to when the owner gives a signal, and not to when a stranger does. Then other dogs, I guess you could say are a little bit more promiscuous about it and don’t seem to care as much about which human gives the signal, although most all of them seem to have stronger responses when the human gives the signal than when a computer does.

CURWOOD: Your project also focused on attempting to discover if canines have what’s known as theory of mind. First, tell us what’s theory of mind, then tell us if you think dogs have this and what would be its value?

BERNS: Sure. So theory of mind is this idea...it’s thought about mostly in regards to humans. So theory of mind is what we would call mentalizing. So far only humans have been definitively identified as having that. Now it’s very controversial whether other species have this capacity. What this would mean is that dogs have some representation not just of what their humans are doing, but also what their humans are thinking or feeling.

CURWOOD: So what implications do you think there are ethically, and say, even legally, to your work discovering how the canine brain works?

BERNS: There are all sorts of implications, not just legally, but also just practically. So on the practical level, we’re trying to understand, in fact, we’re finding out, you know, for example, why certain dogs are better matched to certain people. And this is incredibly important for training, it’s important for developing service dogs, working dogs, and how they interact with humans, it’s important for understanding behavioral problems that occur in dogs which separation anxiety is one of the biggest problems that dog owners face. But on the legal plane, it’s incredibly complicated. So I’ve argued that because we’re finding brain responses that look very similar to human brain responses so much so that we can begin to infer that the dogs are experiencing emotions in many ways like we do, but this argues for treating them something more than property.

CURWOOD: Let’s go back to the question of dog rights for the moment here. Well, so, what about dog rights? At one point as you’re telling the story, you say you decide the dogs would have to volunteer, that they would have to make it clear that they were participating voluntarily in all of this.

BERNS: So we wanted the dogs to do this of their own free will. When I say of their own free will, what that means is, the dogs are not sedated, they’re not restrained in any way, so that means that they have to walk into the scanner and lay down completely on their own, and by doing so, that means that they want to be there. So we came up with this principle of self-determination, which was borrowed from the human research literature. One of the ones which is most sacred in a human is if you volunteer to be in an experiment, you have the right to withdraw from the experiment. We decided that we were going to implement that for the dogs as well.

CURWOOD: By the way, how could the study of the canine brain also help human health?

BERNS: Well, if you accept what I’m saying, that there are many commonalities between the dog brain and the human brain, both the structure and the function, you also immediately realize that they experience many of the same problems that humans do, and I’m speaking specifically emotionally. So one of the things we’ve noticed with regards primarily to anxiety, studying separation anxiety in dogs may very well teach us other anxiety disorders in humans.

CURWOOD: Gregory Berns, is a professor of neuro-economics at Emory University in Atlanta. His new book is called How Dogs Love Us: A Neuroscientist and His Adopted Dog Decode the Canine Brain. Thanks so much, Professor, for taking this time.

BERNS: My pleasure.

CURWOOD: And if you want to see some video of his experiments, please go to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- How Dogs Love Us

- Videos of Dr. Berns’s experiments

[MUSIC: Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band “Tubas In The Moonlight” from Tadpoles (Parlophone Records 1969)]

Small Matters

A flock of birds demonstrate complex patterns in the sky. (Federal Highway Administration)

CURWOOD: Well, the question of how dogs think and feel isn't the only deep mystery being investigated at Emory University. Ari Daniel reports in this latest installment of our Small Matters series, scientists there are also probing the profound mysteries of how patterns and structures form and evolve.

DANIEL: It’s a perfect day here.

[LEAVES CRUNCHING]

Jay Goodwin walks over to a bench to sit down. And he can’t help but be reminded about a day just like this one, five years ago, in western Michigan where he used to live.

GOODWIN: I was outside – I think I was going for a walk, just to kind of clear my head a little bit. I turned a corner, and I saw this flock of birds and they took off into the sky and they started to form a shape – sort of an amorphous shape. And it was one that was dynamic, and it was changing – but it had a boundary to it, like looking at a blob of oil in water.

DANIEL: It stopped Goodwin in his tracks. Several hundred birds pulsing and dipping and soaring to an invisible beat in the sky.

GOODWIN: It wasn’t clear what they were responding to – there weren’t any predator birds in the sky. And you never got the sense that there was anything that was directing it from within. There was no leader bird that they were all following. But just watching it was, well, it was beautiful.

DANIEL: Goodwin realized he had no way of predicting the flock’s behavior by simply taking lots of individual birds flapping their wings, and adding them up. Rather, it was something that emerged once all these birds threw themselves together. And it’s this notion of emergence – how really complex patterns and properties can arise from combining somewhat simple units – that now defines how Goodwin thinks about his real work. Chemistry.

[SOUND OF DOOR UNLOCKING]

Goodwin heads into his lab at Emory University. He’s a chemist here. And since seeing that flock, he’s come to appreciate how molecules are a lot like birds. That is – you get to know how the individuals behave and parade on their own, but then you put them together, and often something new and astonishing emerges.

GOODWIN: We always want to allow some room for serendipity – and allowing the molecules themselves to show us what they’re capable of doing.

DANIEL: Let’s take an example; a glass of water.

GOODWIN: Water molecules in the liquid form are tumbling past each other, and they see each other very dynamically, very quickly, and they move on.

DANIEL: Now cool that water down. The movement of the water molecules begins to slow, and they spend more time kind of looking at each other.

GOODWIN: And they begin to align with each other, and become solid. And they grab more water molecules out of solution as they slow down, and that process begins to propagate and to grow until the whole thing is one big lattice of solid ice.

DANIEL: And the thing about ice – it floats on water. We take that for granted, but most solids sink to the bottom of their liquid form because they’re more dense. Not water, it floats – which is crucial for life.

GOODWIN: Underneath ice in a lake or an ocean or the Arctic is liquid water. That’s one of the unique features of water. That’s an emergent property.

DANIEL: Emergent, because it’s just what happens when you throw a bunch of water molecules together, and cool them down.

Now, Goodwin doesn’t study water. He’s curious about other things, like how, in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, a single misshapen protein can trigger neighboring proteins to buckle and warp, until a tangled plaque has emerged, like an errant bird reshaping its entire flock. Goodwin also studies what might have happened on the Earth a few billion years ago – trying to learn the rules of how simple molecules might have assembled to lead to the emergence of life. Emergence, it turns out, is everywhere.

GOLDBART: There’s no particular reason why emergence should be a property that happens at the scale of atoms and molecules, but not at the scale of - let’s say viruses, or even galaxies for that matter.

DANIEL: Paul Goldbart is a physicist at Georgia Tech who studies how the building blocks of matter interact to form the very small, the very big, and everything in between. He says it’s like watching a dance – knowing that the whole isn’t just greater than the sum of the parts – it’s wondrously different.

GOLDBART: We marvel at the way matter organizes. Not only do we get to see beauty and organization and patterns, but also they’re useful to better society and provide services and materials that make our lives safer and more vibrant.

[SOUND OF GLASS FLASKS BUMPING TOGETHER]

DANIEL: Back in the lab, this is exactly what Jay Goodwin is doing. Harnessing the idea of emergence, by putting molecules together and watching what happens, by creating room for his chemistry to surprise him – and then, turning those insights to use.

GOODWIN: To understanding disease and how to solve disease, and how to develop new therapeutics, how to create new materials that could be intelligent, that could respond to their environments in different ways – could be self-healing, could capture solar energy for instance.

DANIEL: Goodwin’s aim has become one of taking advantage of the rules that determine how molecules behave. Rules that are somewhat mysterious, and can emerge when you take the time to appreciate that they’re there.

For Living on Earth, I'm Ari Daniel.

CURWOOD: Our series, Small Matters, is produced by the Center for Chemical Evolution, with support from the National Science Foundation and NASA.

Related link:

Small Matters

[MUSIC: Jimi Hendrix “Villanova Junction Blues” from People, Hell & Angels (Columbia Legacy Records 2013)]

URWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, all kinds of people take on the challenge of climbing to the highest point in each state.

BURKE: We’ve had the youngest person to reach a highpoint, Natalie Smith is 11 days old and that was the state of Pennsylvania. Dave Johnson has done all 50 state highpoints in the winter. That is quite an accomplishment.

CURWOOD: A day out with the Highpointers. Next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Kathryn Rodway, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director.

Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page, it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Wen Stevenson, Bill McKibben, Mark Hertsgaard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth