July 4, 2014

Air Date: July 4, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Fight To Save the Elephants

View the page for this story

Elephant poaching and illegal ivory trafficking have skyrocketed in the last decade. Just last year, poachers killed more than 20,000 elephant in Africa. But as Leigh Henry of the World Wildlife Fund explains to host Steve Curwood, there is strong international action planned to crack down on the illegal ivory trade. (06:30)

WildLeaks

View the page for this story

WildLeaks, loosely modelled on WikiLeaks, is an organization and unique online platform to collect anonymous tips about wildlife poaching, trade and illegal deforestation. WildLeaks Founder, Andrea Crosta, tells host Steve Curwood how they use this information to fight wildlife crime and prosecute the people involved. (05:55)

At Home With Humba, the Mountain Gorilla

/ Karen LoweView the page for this story

Led by park rangers, journalist Karen Lowe heads into Virunga National Park in the Congo in search of Humba, leader of a troop of endangered mountain gorillas. Charcoal traders, oil drilling and rebels exploit the region, and threaten the gorillas, their habitat and the rangers’ lives. But as Karen explains to host Steve Curwood, there is good news, as the oil company conducting testing has promised to suspend activities in the park, and money is flowing in to support ecotourism. (19:45)

Science Note—Loss of Large Grazing Mammals Alters African Savannas

/ Lauren HinkelView the page for this story

In this Note on Emerging Science, Lauren Hinkel reports on an experiment in Kenya grasslands, where researchers discovered a dramatic shift in ecosystem species when large, native herbivores were removed. This suggests better ways to manage the competition between domestic cattle, people and wildlife. (02:10)

A Window On Eternity

View the page for this story

Pulitzer Prize winning author and Harvard biologist, E.O. Wilson, talks to Steve Curwood about his new book A Window on Eternity. Wilson describes Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park and its many unique and extraordinary species and how biologists were able to reintroduce large mammals like hippos and buffalo after they were wiped out in a series of armed conflicts. (12:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Leigh Henry, Andrea Crosta, E.O. Wilson

REPORTERS: Lauren Hinkel, Karen Lowe

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Conversation with endangered mountain gorillas, as they struggle to hold their own in the unsettled Congo, even in National Parks.

MBRUMBRWE: Before reaching the gorilla you have just to give the signs [grunt] just to communicate with the gorilla so that it can just remember that this guy is my friend; it's not the enemy.

CURWOOD: Tourists love them, but the locals can be murderous. Also conversation with one of the towering figures of evolutionary biology, E.O. Wilson, about his passion for restoring a park in Mozambique, and some quirky African ants.

WILSON: The army passes on through, and it's caught, massacred, and it's carrying off as food every cockroach, every lizard, every kind of spider. Anything it finds in the house, it cleans out.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies–innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

The Fight To Save the Elephants

An elephant in Tsavo East National Park, where Satao spent much of his time and was killed by poachers. (Photo: Donald Macauley; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Increased demand for ivory has fuelled a sharp increase in ivory smuggling and elephant poaching in the last decade. The price of raw, uncarved ivory has risen from a little under $1,000 dollars to $1,500 dollars a pound today, and the number of elephants being killed in Africa has skyrocketed. Some countries are cracking down on the illegal ivory trade, but Leigh Henry, the Senior Policy Advisor of Wildlife Conservation and Advocacy for the World Wildlife Fund in Washington, says there is still work to do. She joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

HENRY: Thanks so much. Happy to be here.

CURWOOD: The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, it’s called CITES for short, has just released a report estimating that poachers killed 20,000 African elephants in 2013. Leigh, can you put that number in context for us and explain what it means for the African elephant population?

HENRY: Sure. It's obviously a huge number, and that number means that we’re losing more elephants every year than that population can reproduce. So it means that we are in the midst of a poaching crisis, and we need to take strong steps to make sure that that poaching crisis is brought to an end.

CURWOOD: Ivory has been considered valuable for a long, long time so elephants have always been a target for poachers. Once elephants were put off-limits back in the '80s, it seemed that poaching died down. Why has it come back was such a vengeance, do you think?

HENRY: So there a couple of reasons, I think. The consumer markets like China and Thailand have more disposable income and more wealth than they did back in the 1980s, and higher prices are now being sought for ivory products. That means that the profit to be made from the illegal ivory trade is much higher and the risks are very minimal. So now we’re seeing international criminal gangs coming in and poaching and conducting the illegal trade. They have resources like helicopters and night vision goggles. They have veterinary tranquilizers they're using to put down the animals which is much simpler to use than bullets, and they have access to trafficking networks that also traffic in drugs and arms and other commodities. And they know how to shift those routes when needed; when enforcement is increased in one port, they simply shift to another port. So it's a really difficult nut to crack.

CURWOOD: What countries are key to this poaching and ivory trafficking problem?

HENRY: So all of the African elephant range states are being hit. There are hot pockets like central Africa where we’re seeing forest elephants which are in the greatest peril, but it's rampant—it’s all across the continent. The other piece that we need to look at are the consumer states that are driving the demand, and those are mainly countries in Asia, but also include the United States and some European countries as well. And what we're trying to focus on more and more is that the burden should not be borne only by the countries in Africa where these elephants live, but that there's a responsibility of the countries where the ivory is being consumed to step up and do their part.

CURWOOD: You say that central Africa is a particular problem. Why there?

HENRY: I think when you look at the issues there with government instability and insurgencies that that's part of the problem. When you don't have stable governments and resources being put in good governance you see you porous borders and insurgent groups and poachers coming into those countries, and the elephants are easy pickings. It has to be a constant effort and a constant presence to protect these elephants because where they’re not protected, the profits are so high the poachers are going to find a way to get in there and get those elephants.

CURWOOD: What's being done overall to crackdown on the illegal ivory trade around the world, and particularly, what about here in the US?

HENRY: So we’ve seen a lot of very high-level political progress and political will built up on this issue over the last year or so. We’ve seen that with President Obama’s Executive Order and the resulting national strategy on wildlife trafficking in the US that’s asking all US government agencies to coordinate to fight this battle against wildlife trafficking. We’ve seen the London conference held by the UK government in partnership with the royal family that brought governments together to sign on to a declaration to take the steps needed to fight wildlife crime, and we also saw great results at the last CITES meeting in Bangkok last March where some of the worst offending countries in illegal ivory trade were held to account—they were given the threat of compliance measures or sanctions if progress wasn’t made. We need to be willing to hold them to account, and that hasn't happened the way it should, and that's what we're hoping we will see the week of July 7th when the CITES standing committee comes together to meet and to review progress against these elephant ivory action plans that we saw come out of the last CITES meeting in March in Bangkok.

Illegal ivory disguised as African artifacts. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service seized these pieces in 2011. (Photo: USFWS; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: What about the penalties for trafficking in ivory?

HENRY: We’re seeing a little bit of an increase, but this is a huge part of the problem. So one of the things that WWF and our partners and the US government have all been working on over the past few years is ensuring that those penalties are increased, and that wildlife trafficking is viewed as a serious crime with commensurate penalties. So, four years and up of prison sentences and high fines so that the poachers and the traffickers find that the risks outweigh the benefits.

CURWOOD: Now I know you're based in Washington, but I know you've also spent a fair bit of time out in the field with elephants. What is there about elephants in your view makes them being targeted by poachers such a tragedy?

HENRY: They're amazing animals, and I think the part that really gets me is they have amazing family bonds and family ties. So when you go in and take one elephant away it's not unnoticed by that group. They hurt and feel the same way we do, and they have a key role to play in their ecosystem. There are also negative impacts on communities and economies especially in countries like Kenya where there is such a huge, huge tourism industry that's dependent on these animals, and then we look at the rangers as well who are trying to protect these animals and they often don't have any of the weapons or technology to defend themselves that they should. And we’re seeing rangers killed when they're trying to protect these animals, so I think it's really important for people not just to think about elephants, but to think about the broad-brush negative impacts of the poaching as well.

CURWOOD: Leigh Henry is Senior Policy Advisor of Wildlife Conservation and Advocacy for the World Wildlife Fund in Washington, D.C. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Leigh.

HENRY: Thank you so much. I really appreciate it.

Related links:

- The CITES report, including how CITES estimates the number of elephants killed by poachers

- Read about Satao’s death

- The World Wildlife Fund

WildLeaks

Poachers’ camp with elephant tusk bounty (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: Well, one problem with deterring poaching is a lack of reliable information, but a new watchdog is on the beat—called WildLeaks. It’s a WikiLeaks-style of website, created by a group called the Elephant Action League, and it is the first secure online platform that allows whistleblowers and the public to post information anonymously about illegal poaching.

Andrea Crosta is the Executive Director of the Elephant Action League and Founder of WildLeaks. He joins us today. Welcome to Living on Earth.

CROSTA: My pleasure.

CURWOOD: What exactly is WildLeaks?

WildLeaks Logo (Photo: WildLeaks.org)

CROSTA: WildLeaks is a platform, but also a methodology and a group of people focused on the collection of confidential information about wildlife and forest crimes, and to facilitate the identification, arrest and prosecution of anybody—criminals, traffickers, businessmen, corrupt government officials--behind wildlife crime.

CURWOOD: How do you plan to do this?

CROSTA: We have a network of people—organizations, professionals, experts—around the world that are really helping us. And of course we are developing also relations with law enforcement because at the end of the day, if you want these people, you know, behind bars you need the judicial system that prosecutes these people. Or you decide to go with the media, and so you basically shame them; that’s the second option we have.

CURWOOD: So as far as you can tell, how big is wildlife crime and the illegal forest removal?

Seized ivory slated for destruction (Photo: Gavin Shire/ USFWS)

CROSTA: Well, it depends. If you put wildlife and forestry crime together, we’re talking about billions of dollars of an illegal market. It’s one of the largest illegal markets on the planet after drugs and weapons and human trafficking. At the same time, unlike, for example drugs, it’s a very low-risk dirty business because if they get you with a load of drugs—of cocaine, of heroin—in most of the countries you go to jail for a long time. In some other countries, you also get executed. If they find you with a rhino horn, and a rhino horn can fetch up to $250,000 dollars for just up to one horn in Asia, well, in most countries, you get a slap on the wrist. So you can imagine it’s the perfect business for criminals that exploit other people to do the dirty job.

CURWOOD: Now, what's the inspiration for WildLeaks?

CROSTA: You know, I’ve been dealing with conservation for more than twenty years, but also I've been involved as a security consultant to law enforcement. And I realized that there's a lot of people out there with a lot of information about wildlife crime, they just don't know what to do with this information. So I wanted to create something to fill the gap between people with information and people that can do something with information.

Andrea Crosta, Founder and Project Leader of WildLeaks (Photo: WildLeaks.org)

CURWOOD: So let's say that I observed somebody poaching an elephant someplace. How would I get to WildLeaks?

CROSTA: So WildLeaks has an online platform, WildLeaks.org. Through this platform, you access to a very secure part of our website, and over there you can submit in total anonymity, not just your message, but you can also upload all kinds of files: videos, pictures, documents, PDFs, whatever you have. You can also write to us through our contact form, which is encrypted. And WildLeaks is not just a passive receiver; we have teams in the field, so people contact WildLeaks also personally. So there are people that have information, so you meet them. So in this way you slowly build a relation with potential whistleblowers, potential sources, in the hope that they would provide critical information which we can seriously act on the important people behind wildlife crime.

Poachers sell elephant legs for furniture (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: So there’s billions of dollars at stake in illegal trade in wildlife, which means your organization’s going to be a target for people who do that. How you guard against them hacking your website to a) maybe find out who's giving information and b) try to put you out of business?

CROSTA: Right. Well, first of all, we’re not the only ones who fight this battle; we are many. We, of course, take a lot of precautions to protect our data, for example, the server of WildLeaks is a very secure server. We don’t have permanent personnel in target countries like Africa or Asia because the moment you have people there, they become a liability. So, these are general precautions that we take in order to protect our data and our people. Of course, there is always the risk of a cyberattack—we’ve actually been attacked a couple of days ago—but we are very well protected. The maximum they can get is to have our website down for a few hours, and then we’re up again.

Animal heads left after poaching (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: What kind of tips have you received so far; I gather you began operating in February?

CROSTA: Exactly, we are just four months old. Actually we got dozens and dozens of tips and leaks and different kinds of information that were accessed. All-in-all we came up with twenty-four leaks that our assessment group assessed as good and reliable. We are about to investigate on three of them already. And the topics that we receive varies a lot, but we got quite a bit about ivory trafficking, not just in Africa but also in Asia, which is the destination of ivory. And we also got information about the illegal logging in Central Africa, illegal logging in Russia, illegal fishing in the States, poaching in the United States, trafficking of chimps in Liberia. So we are very happy with the reaction of the public. It looks like we kind of fill a gap.

CURWOOD: Andrea Crosta is the Project Leader and Founder of WildLeaks and Executive Director of its partner organization, the Elephant Action League. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

CROSTA: My pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Visit WildLeaks’ website

- Elephant Action League and WildLeaks partner to curtail wildlife crime

- Read more about wildlife crime here

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell “Boubacar” from The Intercontinentals (Nonesuch Records 2003)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: tenuous times for mountain gorillas in the war-torn Congo. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: George Benson: “Breezin” from Breezin (Warner Bros 1976)]

At Home With Humba, the Mountain Gorilla

The silverback, Humba, is relaxed yet imposing around people. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Almost a century ago, in a vast expanse of Central Africa known as the Belgian Congo, King Albert I of Belgium decreed the continent's first national park to protect key-habitat for our biggest and most impressive relative, the mountain gorilla. The park still survives. Today it's known as Virunga National Park, in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC, but a series of wars and rebellions since independence in 1960 have killed more than five-million people, and protecting almost everything there has been a challenge. There are still gorillas, but they are in deep trouble. Reporter Karen Lowe recently traveled to Virunga where one of the park rangers, Innocent Mbrumbrwe, led her deep into the forest in search of gorillas.

Makawamwe, a blackback in the Humba family living in the Mikeno sector of the Virunga National Park, watches over the family as visitors approach. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

MBRUMBRWE: I can say it’s because I love them. Every time when I'm with these animals I feel very good to be with these gorillas because they are like humans.

CURWOOD: Here's Karen's report.

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

LOWE: When trekking through Virunga National park, your senses are always on overdrive. You don’t want to miss anything. Virunga has rainforests and volcanoes. Its savannah wildlife rivals the Serengeti. The source of the Nile is here. It has the largest lava lake on Earth, and glaciers. There are at least one-thousand species of animals, including some odd ones, like the Okapi. It looks like a cross between a zebra and a giraffe. Or the recently-discovered Lesula monkey with a human-looking, professorial face.

Ranger Innocent Mbruwamwe looks for signs that the Humba troop in the forest. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

But the marquee draw—the reason most people come—is the mountain gorilla, the world’s largest primate. The species is on the critically endangered list. There are only eight-hundred and eighty in the world and a quarter of them live here.

MBRUMBRWE: Are you ready? Put the mask on.

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

LOWE: Right now, I’m following Innocent Mbrumbrwe.

[WALKING IN THE BRUSH AND HACKING AT THE FOLIAGE]

We’re looking for one gorilla in particular: Humba, a silverback with about 20 family members. Innocent’s a 38 year-old ranger and an expert on mountain gorillas. He runs the park’s southern sector. We’re flanked by two other rangers with machetes and AK-47s, just in case we encounter hostile rebels and charcoal traders.

MBRUMBRWE: Every time you have to be together.

LOWE: Nearly one-hundred and fifty rangers have been killed since this country descended into war almost twenty years ago. Just before I arrived, one ranger was killed and two were injured.

After Innocent spent years acclimating the gorillas to human presence, Humba, the silverback, is quite at ease with visitors. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

The gorillas are deep in the forest, and to get to them, you have to hack your way in.

[SOUNDS OF HACKING WITH MACHETES]

LOWE: Vegetation is so thick that visibility is only a few feet. But honestly, at the moment, I’m not really concerned with gorillas, or even armed rebels; I’m worried about the giant Congo spiders with six-foot leg spans. I carefully place my foot exactly where Innocent has just lifted his. But vines wrap around my ankles, and I become a sweaty mess trying to keep up with Innocent.

Reporter Karen Lowe returning from the visit to the gorillas. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

MBRUMBRWE: Come on.

LOWE: He patiently waits for me to pull myself together. He’s cool. Not even a crease in his uniform. Innocent is formal in the field, but when he sits and talks about his relationship with the gorillas, he softens.

MBRUMBRWE: I can say it’s because I love them. Every time when I'm with these animals I feel very good to be with these gorillas because they are like humans.

Looking after her baby (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

LOWE: He also offers some tips on gorilla etiquette.

MBRUMBRWE: Before reaching the gorilla you have just to give the signs—meaning, you were just understanding what I was doing [GRUNT] just to communicate with the gorillas, so that it can remember that this guy’s my friend; it's not the enemy.

These are different signs, but some signs are just showing that we are friends. But the other ones are telling to the gorilla, “Please don’t approach me.” For example, this one, “hahmmm.” And another one, it’s like “haaummm.” I am not the enemy. But I just want to play, but not play. Even in the family, they communicate with each other by signs.

LOWE: Innocent spent years learning how to communicate with the gorillas and getting Humba acclimated to humans. Sometimes it got dicey.

MBRUMBRWE: At the beginning, it was very, very aggressive; you know that it’s a wild one. So coming every day, trying to give signs. And you’d see that the silverback is coming; he’s charging; he’s crying. Every individual is beating his chest; he’s coming toward you. Then you say, “Oh my God, what I am going to do?” Now, he is changing; now he’s very quiet, very calm.

LOWE: As we move through the rainforest looking for signs of Humba, Innocent occasionally grunts to announce our presence. He points out some flattened branches. That’s where Humba’s family slept overnight.

MBRUMBRWE: Another female which passed the night here—because the hair it is not white-ish. It’s black.

LOWE: We walk on, and he plucks some gorilla fur from a branch and shows it to me. Then he points down. No explanation needed—gorilla dung. Then we come to one of Humba’s sentinels.

MBRUMBRWE: It is not the chief of the family, but it’s one of their members, Nakamwe.

A female watches over her baby. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

LOWE: They greet each other with the formality of two generals. Standing about ten feet apart, [GRUNTS] they grunt and acknowledge one another respectfully. Innocent negotiates our passage.

[GRUNTS]

The gorilla turns and leads us to his family. We adjust our face masks that we were given to make sure we don’t spread any diseases to the gorillas.

As we get closer to Humba’s troop, a few gorillas beat their chests. They’re showing off for the tourists. And then, there’s Humba. He makes me feel very, very small. Mountain gorillas can weigh nearly five-hundred pounds. Their outstretched arms can measure seven feet across, and fully-grown male can be ten-times stronger than a man. Humba is completely unfazed by us.

He sits on the ground with his back to us and pulls down branches the size of saplings to eat the leaves. At one point, Humba lies on his back and crosses one knee over the other, arms behind his head: total alpha pose.

Humba’s troop and Innocent clearly are at ease with each other. Humba’s name means “peaceful.” Rather than face a fight with another silverback, he’d rather move his brood a safe distance away. I feel safe and move closer to the gorillas, which annoys Innocent a bit. He’s spotted some blood on leaves, which means there’s been some fighting before we came. There are two silverbacks in the group—possibly trouble there. There are about two dozen females, though you don’t see them all at once. But everywhere you turn, if you look closely into the brush, you will see eyes peering back at you.

Curious baby gorillas edge closer to visitors. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

[COUGHING]

LOWE: I cough a few times and each time I do, one of the gorillas does too. They’re mimicking me. Juveniles roll around in play—a ball of fur and feet. A baby grabs for my camera, but Innocent gently shoos him away with branches. Then Humba walks in my direction. I hold my breath as the giant silverback moves past me just a few yards away. You can see the power ripple across his back and shoulders. After about an hour, Innocent tells us we have to leave.

[FOOTSTEPS]

LOWE: As I walk away, I look back at gorillas peacefully eating and playing, and I wonder: Can this last? They face a lot of problems. Potentially the biggest one isn’t even visible yet. The Congolese government granted a London-based oil company rights to explore for oil in an area that would cover about half of the park. The oil company called SOCO is finishing seismic testing in a nearby lake. It’s uncertain what will happen once they’re done. I want to talk to the park warden about this.

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

LOWE: So, the next day I walk over to Mikeno Lodge at Virunga Park headquarters. The Director is Emmanuel de Merode. He’s a primatologist by training and a Belgian prince by birth, though he never mentions that. He’s dressed in a green uniform with a rolled up beret pinned to his shoulder.

A close-up of Humba eating leaves and vines (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

On the day we talk, he’s optimistic about turning the park into an economic engine. He says tourism and agricultural projects, like coffee and cocoa plantations, could generate as many forty-thousand jobs. They’re also building hydroelectric power plants that could generate enough electricity to cover park expenses for the next eighty to one-hundred years. De Merode says if oil is to come, there needs to be enforceable regulations and resources in place because of the potential risks.

DE MERODE: The risks, of course are, have to do with an accident. There isn’t a single oil field on Earth where there hasn’t been an accident. To say there won’t be an accident in Congo is ambitious, I’d say.

The other issue of course is all the spin-off effects of an activity like that, that need to be managed very, very carefully. In economic thinking, they talk about "le mal Hollandais", the Dutch disease. It’s a term that’s used for, when you have a region like this, and suddenly a massive influx of activity tied to a single industry which is oil, it kills off a lot of other activities around it because it just swamps it.

LOWE: And then there are the direct threats inside the park to the gorillas. He recalled the night in July 2007, before he became a park warden, when he and Innocent heard gunshots in the bush.

DE MERODE: So, the next morning we went out and walked through the rain for several hours and eventually came upon a terrible scene, which was the massacre of the Ruwenga group of gorillas. And basically, we found four bodies of the mountain gorillas, and they’d been killed. The fifth one was found several days later. They’d all been shot at very short, close range. One of them had been shot and doused in petrol and set alight. It was a very brutal, very vicious killing.

LOWE: De Merode says the massacre was the work of charcoal traders. They’d been cutting down trees for fuel at an alarming rate. The Congo’s charcoal trade is worth millions. That’s a lot of money here, where the average annual income is $120 dollars a year, and the militias are getting a cut. Park rangers were getting in the way of business.

DE MERODE: The rangers really are on the front line trying to prevent the forests from being destroyed, in particular the gorillas’ habitat. So by killing all the gorillas, these militias were betting on the fact that it would discourage the rangers and stop them from protecting the forest, so that they could access it and make money. It was a very, very violent scene. It was extremely brutal. And for Innocent, it was all the more terrible because that was his lifetime’s work, and it was also his father’s lifetime’s work. His father died protecting those gorillas.

LOWE: At the time of the massacre, de Merode was working with a conservation group and Innocent was leading the rangers. Corrupt officials were blaming him for the attack.

Spent shells collected by rangers from fighting in the bush with rebel groups and charcoal traders. The shells are kept at a patrol station only a 45-minute walk to the Humba troop. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

DE MERODE: And he actually went to prison for it. They were trumped up charges. They accused him of resisting arrest. And they tried to turn things against him, and they tried to blame him for killing of the gorillas—of negligence, of not protecting them adequately. And so, he was arrested and quite badly beaten when he was in prison. We were able to get him out after a few days, and eventually we able to demand an inquiry into the whole thing. And the real people responsible were eventually arrested.

[WALKING WITH BIRDS CHIRPING IN DISTANCE]

LOWE: After that incident, the Congolese government wanted someone who was not caught up in local rivalries to run the park. That meant bringing in an outsider; they offered it to Emmanuel. That was an interesting choice, given that Belgium ruthlessly exploited the Congo when it was a colony. Emmanuel became the only foreign national to have judicial powers in the Congo. His first mission was to find out what was happening with the gorillas. But rebel fighting made it too dangerous to go in. Ultimately, he brokered a deal with all the warring parties to let the rangers back into the gorilla sector.

Conservation Rangers from an Anti-Poaching unit work with locals to evacuate the bodies of four Mountain Gorillas killed in mysterious circumstances in Virunga National Park, Eastern Congo. (Photo: Dawai Ding; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

DE MERODE: We had been away for a very long time because of the war. We crossed the front line and went up into the hills, into the forest, right up into the mountains, and finally saw the Humba group, which we hadn’t seen for fifteen months. And they immediately went to him. So, Humba himself, the silverback, immediately went right up to Innocent, walking past me and the others, and straight to him. So there is no doubt in my mind that he has a very unique relationship with the gorillas.

LOWE: That kind of relationship between the rangers and the gorillas is key for tourism, and if Emmanuel just had to contend with poachers and rebels, his seven-hundred rangers might be able to hold the line. But the prospects for oil in the DRC have dramatically ratcheted up tensions over the past few years. In addition to the shootings, there have been recent death threats against conservation activists. Emmanuel and his rangers took huge personal risks. Innocent has not only buried his father and his brother, but now one of his sons has told him that he, too, wants to be a ranger.

Another view of the spend shells collected by the rangers in Virunga National Park (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

Asked if it’s worth it, Emmanuel is unequivocal.

DE MERODE: That’s not a question you can ask yourself. If you start to ask yourself that question, then it becomes an impossible situation, you know. We have to do our job. It’s just the decision we made when we decided to become rangers.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

LOWE: When we walk back down the mountain out of the park, we stop at the ranger’s post. It’s hard not to notice the spent rocket and mortar shells heaped in a pile on the ground from past combat over the Congo’s riches. One of the great potentials in that conflict is the robust biodiversity of Virunga National Park, and that includes the mountain gorillas.

From the Democratic Republic of Congo, I’m Karen Lowe.

CURWOOD: Karen's trip to Virunga National Park was supported by the International Women in Media Foundation, and she's still on the line with us now. Karen, it sounds like things are pretty tense on the ground there in the Democratic Republic of Congo. What exactly is going on?

LOWE: Right now there is a sense of euphoria among the park rangers and conservationists because SOCO oil has agreed to suspend exploring in the Virunga National Park or any UNESCO World Heritage site around the globe. It is a victory for conservationists, a big one, at least for now. But SOCO will finish what it set out to do—seismic testing for oil on Lake Edward. It is one of East Africa's great lakes and it supports about eighty-thousand people. What this agreement means is after the seismic testing is done, any actual drilling must be done with UNESCO’s blessing.

But this victory came at great cost, and we have to remember SOCO's activities have only been suspended. We still don’t know how things will play out in the long run, and the DRC government still hasn’t said what it will do.

Humba casually nibbles on vines and leaves. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

CURWOOD: What about the conservationists? What kinds of concessions have they made, and how did things change so quickly?

LOWE: As part of the deal, the World Wildlife Fund, which lobbied mightily against SOCO, has agreed to drop its demand for a probe of SOCO. The oil company's publicly traded, and the WWF had alleged SOCO had breached global corporate responsibility standards. It took a long time to get to this point, and there's been a lot of violence over the park. But the thing that probably forced SOCO’s hand was the shooting of Park Director, Emmanuel de Merode.

CURWOOD: What he got shot?

LOWE: Yeah, he was hit four times as he was driving through the park, and he was only five-hundred meters from a military post. He’s okay now. He was treated in Nairobi, and he’s back in the park. But SOCO has condemned the shooting and denied any responsibility for it. De Merode was shot just a few hours after he had delivered to the Congolese prosecutor the results of a three-year investigation. That probe was approved by the Congolese court in 2010. The document contained allegations of intimidation and bribery carried out by those who wanted to open the park to oil exploration and drilling. The investigation is a separate matter from the World Wildlife Fund allegations; so, all of this doesn't just go away.

CURWOOD: What are some of the specific allegations that were in the report delivered by de Merode to the prosecutor?

Baby gorillas keep a curious watch on human visitors. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

LOWE: Basically, that elements of the Congolese government and military, who favored drilling, allegedly used bribery, torture and death threats against activists and park staff. Those threats go back for years and had been getting progressively more violent. The report also says that park authorities found that a SOCO oil representative paid a senior park official several thousand dollars to support SOCO activities. And then that park official later threatened to fire rangers who didn’t go along with the oil development plan. There were also instances of torture. There were some pretty horrific elements too. When the head of the park’s central sector resisted pressure to open the park to oil interests, he and his brother were badly tortured; then their captors paraded the park official through his neighborhood and snuffed out burning cigarettes on his head—a not too subtle message to others.

CURWOOD: What role did international attention play?

LOWE: There was tremendous international pressure applied. The showdown got widespread media coverage, especially after a movie "Virunga" was released. The producers managed to catch on tape some of the shady dealings, and recently Human Rights Watch called on Belgium to investigate the attack on de Merode, who is one of its own nationals.

The Human Rights group also asked the U.K. to investigate—under the UK Bribery Act—whether any of the alleged acts of corruption and bribery might have led to attacks on rangers and activists. If there are violations, SOCO and its officials could face criminal prosecution.

CURWOOD: It seems pretty clear that someone wanted de Merode dead. Who do you think?

LOWE: Yeah, there are a number of parties aside from SOCO who wanted oil drilling to happen, including elements of the military and rebel groups. They always profit from resource extraction in the Congo, and they're not so worried about what’s legal. So they just might have just seen de Merode as someone who’s getting in the way of business.

Most of the time, Humba leads a relaxed life with his family. They spend hours eating, preening and playing. (Photo: Evelyn Iritani)

CURWOOD: So what does de Merode do now?

LOWE: For de Merode, Virunga National Park is a UNESCO World Heritage site, and he’s determined to protect it. He’s driven by what he sees as a perfectly achievable ambition: get the park functioning as a tourism and agricultural enterprise, and a lot more people will benefit from that than they will from oil. And he's got proof right next door: Rwanda endured a horrific genocide fifteen years ago, and it’s pretty much recovered. And a big part of its economy is tourism. It makes about $430 million dollars a year—mostly from tourists who want to see gorillas. So de Merode figures the DRC can do this too, especially since Virunga has more natural attractions.

CURWOOD: So what kind of help is he getting pushing ahead with this?

LOWE: For one thing, the philanthropist Howard Buffet is a huge supporter. He’s an avid environmentalist, and he's also the son of multi-billionaire, Warren Buffet. He’s poured $20 million dollars into hiring park rangers, and getting the lodge ready for luxury tourism and he’s also developing hydroelectric power. The idea there is that if people get electricity they’ll be less likely to burn the forest for charcoal. When I asked Howard Buffet how long he can keep supporting de Merode’s efforts, here’s what he told me.

BUFFET: This is one of those things where there is no second chance. There is no “Well, if it doesn’t work, we’ll go to Plan B.” There is no Plan B; so, you can’t let them do this.

Mountain Gorilla in Virunga National Park (Photo: LuAnne Cadd/ Wikimedia Commons 3.0)

CURWOOD: One last question Karen: How’s Humba doing?

LOWE: Oh, Humba. He suffered a setback. The other silverback in his group challenged his dominance, and as we know, Humba doesn’t like to fight. So that must have been hard on him. Somehow he’s making do with six of the troops’ sixteen females though.

CURWOOD: That's Karen Lowe, just back from the DRC with a tale of its gorillas, the people trying to look after them and the threats still facing them.

Related links:

- Visit the tourism site of Virunga National Park

- Read more about Virunga National Park, DRC

- World Wildlife Fund—Virunga under threat

- Read about and listen to more of Karen Lowe’s work

[MUSIC: Diblo Dibala (Featuring Loketo) “Kelele” from Super Soukous (Shanachie Records 2006)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: lessons from the African savanna. That's ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Michael Pluznick: “Mozambique” from Rhythm Harvest (Narada Equinox Records 2005)]

Science Note—Loss of Large Grazing Mammals Alters African Savannas

Large herbivores, including elephants and giraffes, live on the Kenyan savannas (Photo: Jay Aremac; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Just ahead, E.O. Wilson, one of the most celebrated evolutionary biologists is helping Mozambiqans recreate their park. But first this note on Emerging Science from Lauren Hinkel.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Cattle on a Kenyan ranch (Photo: Luca Esposti; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

HINKEL: When the elephant’s away, the mice will play—at least that’s what researchers from Bard College and UC Davis found in the Kenyan grasslands.

African savannas are among the most productive ecosystems on earth—home to abundant wildlife from large grazing mammals like giraffes and elephants, to small species like mice and snakes. But ranchers also covet the grasslands for cattle, and domestic herds are increasingly displacing native species.

The researchers designed a long-term experiment on Kenya’s Laikipia plateau to assess how the removal of large, native herbivores affected the savanna ecosystem.

Grazing Grevy’s Zebra (Photo: Kevin Walsh; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

They set up eighteen plots of land enclosed by electric fences at varied heights, which allowed different combinations of cattle and wildlife to interact. For over 15 years, the researchers tracked all the wildlife on each plot, from zebras and insects to the savanna’s only species of tree—the whistling thorn.

The northern pouched mouse (Saccostomus mearnsi) is the dominant small mammal in the savanna habitat of central Kenya, where the Kenya Long-term Exclosure Experiment is located. These mice represented 85% of the small mammals captured over 11 years. (Photo: Felicia Keesing)

They saw a profound ecosystem shift on the plots that lacked large grazing mammals, and consequently grew longer grass. Most notably, a rodent called the pouched mouse thrived, and brought with it parasites and predators: fleas, ticks and venomous snakes. The researchers speculated that these creatures would bite more people and animals, increasing medical problems and disease in the region. Also, the growing mouse population voraciously consumed whistling thorn seedlings. This impacted the whole ecosystem, as the trees provided food and shade for herbivores, hiding places for predators and fuel for people.

Though the loss of large grazing mammals caused unexpected consequences, researchers are optimistic that now they understand the effects, careful land management of the savannas can strike a balance so that both cattle and wildlife can have their grass and eat it too.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Lauren Hinkel.

Related links:

- Read more about the Kenya Long-term Enclosure Experiment (KLEE)

- Read the study in BioScience

- Another KLEE study: Africa's poison 'apple' provides common ground for saving elephants, raising livestock

A Window On Eternity

Elephant in tall grasses (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Michael Paredes)

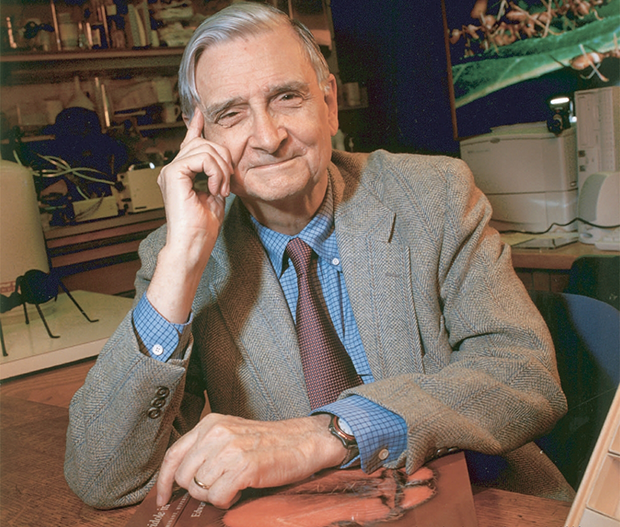

CURWOOD: Pulitzer Prize winning author and Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson is perhaps best-known for his detailed work on ants. But Professor Wilson recently traveled to Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique to study wildlife on a much larger scale—elephants, baboons, buffalo—as the park rebuilds from the loss of almost all of its large animals during armed conflicts. His new book detailing this experience is called A Window on Eternity, A Biologist's Walk Through Gorongosa National Park. Professor Wilson stopped by our studio to talk about the park.

Elephants (Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)

WILSON: The main vegetation of Gorongosa Park is savanna and seasonal dry forest. It is an environment in which humanity evolved. Every species of organism that is mobile—that is, moves around—has a favored habitat, and I believe the same thing is true of human beings—that we have an ideal habitat. And that habitat would be the one in which our species evolved, and if that's true it helps to explain why the African savanna, exemplified so marvelously by Gorongosa, has inspired poets, novelists, all kinds of people to say essentially the same thing: “I felt at home here. I felt good. I really like this place.” They saw this part of Africa, particularly around the great African drift, as something special, emotionally.

The savanna of Gorongosa National Park (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Piotr Naskrecki)

CURWOOD: At Gorongosa, the war there in Mozambique between the government and the RENAMO, supported by the apartheid of South Africa, meant that virtually all the large, the megafauna—the big animals: hippos, elephants, lions—I think in your book you say everything down to about ten kilograms; twenty, twenty-two pounds was pretty much eaten. But now today a lot of animals have returned. What's there now, and how are they able to make this return?

E. O. Wilson (Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)

WILSON: Yes, a few species did survive in small numbers, maybe a dozen or so elephants. There were a couple of Cape buffalo and so on, and Greg Carr, who’s been masterminding the re-building of the game, the big animals, got animals for breeding purposes, and released them from the surrounding countries. And so we are in the process of building up a healthy lion population; as they say, what a wonderful thing to hear the roar of these returning lions around you in the dark, in the evening. And every other species except for a few that are just too dicey to get back in right away, including the cheetah, is being returned.

During Mozambique’s series of wars almost all large animals, such as hippos, were eradicated from Gorongosa National Park. (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Steve Le Vourch)

CURWOOD: Let’s talk for a moment about the elephants in the park. There’s a small population there and some of them must have been there during the Civil War as well. Biologists speculate that they're living with something akin to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Could you tell me about that—what you saw, what you heard?

The elephants of Gorongosa Park suffered from something akin to PTSD following the years of conflict in Mozambique. (Photo: Gorongosa National Park)

WILSON: Yeah. They’re the most aggressive elephants in Africa, and the reason appears evident that a few young elephants witnessed the slaughter, brutal slaughter, of their brothers, sisters, their parents and so on. These young elephants that had the trauma survived, as matriarchs today, and they visibly are agitated by the approach of people. They are much shyer than elephants elsewhere, and they’re much more likely to charge if you get them in any kind of a situation where they appear trapped. But there're easing up now. One of the leading authorities on elephant biology and behavior, Joyce Poole and her brother Bob Poole, they went out and over long period of time, simply parked near browsing elephants and did nothing—just sat there talking quietly. Gradually the elephants calmed down. They “habituated,” is a word we use in animal behavior, to the two humans. And the result is, they’re much more peaceful, but you're advised not to go out alone, stand in front of a matriarch and wave a big flag or something.

E. O. Wilson examines an orb weaver spider web. (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Bob Poole)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Now part of your reason for traveling to Gorongosa National Park is to catalog its diversity, particularly the diversity of insects, spiders living in specific areas within the park today, and you call part of that effort, a bio-blitz. Please tell me about a bio-blitz and what you found.

A lion from Gorongosa National Park (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Michael Dos Santos)

WILSON: Well, a bio-blitz really—I conducted the first one in Gorongosa—and the idea is bringing people into the study of biodiversity, and it's especially effective with school kids—to invite everyone in, to join in a search for all organisms, and make a complete census. And included among all the invitees, of course, are all the experts that might or might not be in the area to assist in this. And it’s sort of a combination treasure hurt, serious natural history search, and just community activity, which is wonderful. We are just beginning to find out what’s in that park. In a model, for example, the great Smoky Mountain National Park, one of the few parks in the world that is striving for complete census of its biodiversity, have yielded eighteen-thousand species of organisms, with an estimate of as many as sixty-thousand present. In a tropical, extremely rich environment like Gorongosa, I think we're eventually going to find into the hundreds of thousands of species of organisms in that one park. And it’s then we can come fully to understand how these ecosystems work. Here then is an area for pioneering in a major part of biology.

A local researcher observes Matabele ants. (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Piotr Naskrecki)

CURWOOD: Now your expertise and some of your fame, of course, could be attributed to the studies that you’ve done on ants. In your book, A Window on Eternity, you talk about the Matabele ants and what they do to termites. Could you describe that for me please?

WILSON: Oh, yes. Everywhere you go in the park, you're likely to find an army of Matabele ants crossing the trail. Big black heavily-armored warrior ants moving in a group of anywhere from maybe fifty or a hundred to over a thousand. They are moving in a way I have never encountered in any other social insects, ants, termites or whatever, as a solid group—all of them close to the fellow ants around it and all moving in the same—as one body of ants charging along. You see them crossing the road, and it’s part of the wildlife spectacles of Gorongosa because the local people have a custom, superstition: do not cross or ride over a Matabele column; it’s bad luck. The column is on its way. They've been aroused in their nest by scouts.

Ants (Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)

Scout Matabeles can be seen out wandering the ground, the countryside out as much as a hundred yards, and when a scout finds a termite nest or opening into one that allows an army to come, to break in, it runs straight back to the nest. And by means of some communication we do not know, arouses the warrior ants, the adults, and out they come in a solid body marching together, behind the scout ant. They arrive at the termite nest, and they just crash through the entrance. And the termite mound—termite nest, I should say—responds by sending down, or in that direction, large numbers of soldier termites. So what ensues in the mounds and all around the entrance is open battle between the Matabele and the termites, which are smaller, they’re armed, but their soldiers are smaller. And the Matabele ants always win. The termite soldiers are always killed. And as the battle subsides, each Matabele worker gathers up as many dead soldiers or termites as it can and almost by signal, the entire group, each one carrying a bunch of dead soldiers in its mandible, marches in the same formation back. And at the nest, they eat the termite soldiers. That’s what the Matabele feed on—they’re specialists. In other words, they go to war in order to collect dead soldiers of the enemy for dinner.

An image from E.O. Wilson’s book, A Window on Eternity (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Piotr Naskrecki)

CURWOOD: Interesting way to live and eat. Tell me about the ants that would clean your house.

WILSON: Driver ants which is what you’re referring to.

CURWOOD: Yes.

WILSON: They have swarms of up into the millions because each colony can have over twenty-million workers, always under orders of the single queen. People have known for millennia that when these Driver ants arrive at your house, get out of their way and let them go into the house, and just go away and have a cold drink somewhere. After a few hours, the army passes on through, and it's caught, massacred, carrying all this food, every cockroach, every lizard, every kind of spider or anything it finds in the house, it cleans out. And as the army of Driver ants recedes in the distance, why, you can return home—a home that’s been perfectly cleaned for you.

[LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: What are the take-home lessons from your time at Gorongosa?

E. O. Wilson is a biologist and author. (Photo: Wikipedia Commons)

WILSON: There are a number of take-home lessons in Gorongosa. We have in Gorongosa, as we do in parks elsewhere around the world preserved at least to an important degree, these immensely complicated ecosystems. And they evolved over three-and-a-half billion years, overall globally, three-and-a-half billion years to what they are today. And we’re not going to find out how they work any more quickly than we’re going to find out exactly how the human mind works. So we should regard this as a major area for future biological research and not just an interesting place to visit. We should plan land-use globally that includes substantial parts of the world set aside for the rest of life, and allow it to continue indefinite time, eternity if you will, on its own like a parallel universe as we learn more and more about it.

CURWOOD: E.O. Wilson’s new book is called, A Window on Eternity, A Biologist's Walk Through Gorongosa National Park. Professor Wilson, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WILSON: It’s been a privilege.

Related links:

- More on E.O. Wilson’s book, A Window on Eternity

- E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation

[MUSIC: Hugh Masakela “Happy Mama” from Live At The Market Theater (Shear Sound Music 2006)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, Abi Nighthill, Jennifer Marquis and Olivia Powers all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page—it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment—supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth