October 10, 2014

Air Date: October 10, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

In Hotter (Sea) Water

View the page for this story

As the climate warms, scientists are increasingly concerned about where the atmosphere’s heat has gone. Host Steve Curwood discusses new measurements in a study that has found estimates of ocean warming off by more than 25 percent, with Dr. Paul Durack of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Harvard Prof. James McCarthy, tells Steve Curwood that while this answers some questions, there are still mysteries in the deep ocean. (06:20)

Mercury in Coal Dust Poses Wetland Threat

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

With recent proposals to bring coal by rail through the Pacific Northwest for export to Asia, some scientists worry that coal dust containing mercury might contaminate Washington’s wetlands, threatening wildlife. Reporter Ashley Ahearn treks through marshes and muck near railways with USGS scientists as they look for coal’s potential impacts on wetland ecosystems. (04:55)

China's Energy Efficiency Program Still Promotes Global Warming

View the page for this story

Despite China’s improved energy efficiency in recent years, economics professor Dabo Guan tells host Steve Curwood that rapid growth has led to an overall increase in CO2 emissions. (05:00)

China's Great Frack Forward

View the page for this story

Facing an unprecedented air pollution crisis caused largely by coal, China is looking to its massive natural gas reserves for cleaner burning energy. But as Mother Jones reporter James West tells host Steve Curwood, fracking is bringing new environmental problems to rural Chinese communities. (10:30)

China's Online Environmental Activism

/ Allison GrinerView the page for this story

Fighting for clean air and water, China’s environmental activists are turning to social media to mobilize support. Allison Griner reports from Beijing. (06:25)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about stolen beaches, and the impact of the NAFTA trade agreement two decades later.( (04:30)

Years of Living Dangerously

View the page for this story

Hollywood Director James Cameron won a 2014 non-fiction EMMY for the TV documentary, Years of Living Dangerously that he produced. With celebrity hosts, the series covered the globe and laid out the gravity of climate change. The series is now released on DVD and Cameron discussed the show and its message with host Steve Curwood. (09:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Paul Durack, James McCarthy, Dabo Guan, James West, James Cameron

REPORTERS: Ashley Ahearn, Allison Griner, Peter Dykstra

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living On Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. New data tell us climate change has warmed the upper ocean more than we thought, but there’s a lot we still don’t know.

MCCARTHY: The big mystery that still remains is: what’s happening even deeper than 2,000 meters. Some people say, you know, we know more about the surface of the moon than we do the deep ocean. We know more about Mars than we do parts of the deep ocean.

CURWOOD: Also, the award-winning documentary series “Years of Living Dangerously” used celebrity reporters like Harrison Ford, who confronted an official about illegal logging.

FORD: We were in Tesso Nilo.

HASAN: Mmmm, Tesso Nilo. [LAUGHS] OK.

FORD: National park. It's not funny.

HASAN: Yeah.

FORD: Only 18 percent of it remains. There are new, illegal roads. Forests cut, trees lying on the ground. It's heartbreaking to see it.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living On Earth comes from United Technologies innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

In Hotter (Sea) Water

The NOAA ship Ka'imimoana was used to launch Argo floats into the ocean. (Photo NOAA; CC Government)

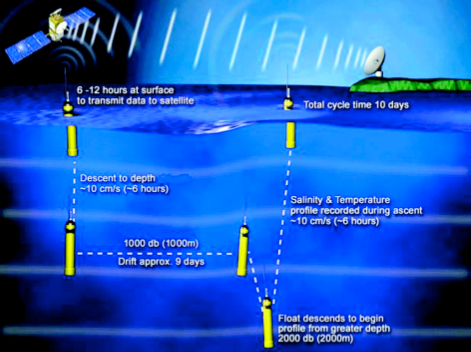

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Science tells us that burning lots of fossil fuel and cutting down lots of trees is warming the Earth, but just how fast and where all the added heat is going has been unclear, though the oceans seem most likely. Now new research based on temperature readings taken over the past decade of the upper half of the seas, is bringing more clarity - and concern. It’s based on the international program called Argo that by 2004 had deployed some 3,500 robotic buoys measuring sea temperatures down to 6,000 feet. Dr. Paul Durack and his colleagues at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory compared the new Argo data with ocean models and satellite readings of the ocean surface.

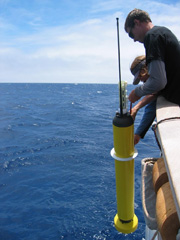

Scientists deploy an Argo float off of the side of a NOAA research vessel. (Photo NOAA; CC Government)

DURACK: So, what we actually did was we’re basically revisiting estimates of temperature changes in the ocean. And what we found was that there’s an underestimate of how the oceans are warming by a factor of 25 percent or more due to poor sampling of the southern hemisphere that this study has uncovered. So, it’s really not a small adjustment when we consider this analysis with the measurements of ocean warming.

CURWOOD: Some suggest these data indicate the earth is warming at the faster end of current estimates, but as Professor James McCarthy, a Harvard oceanographer points out, there’s still a lot to learn.

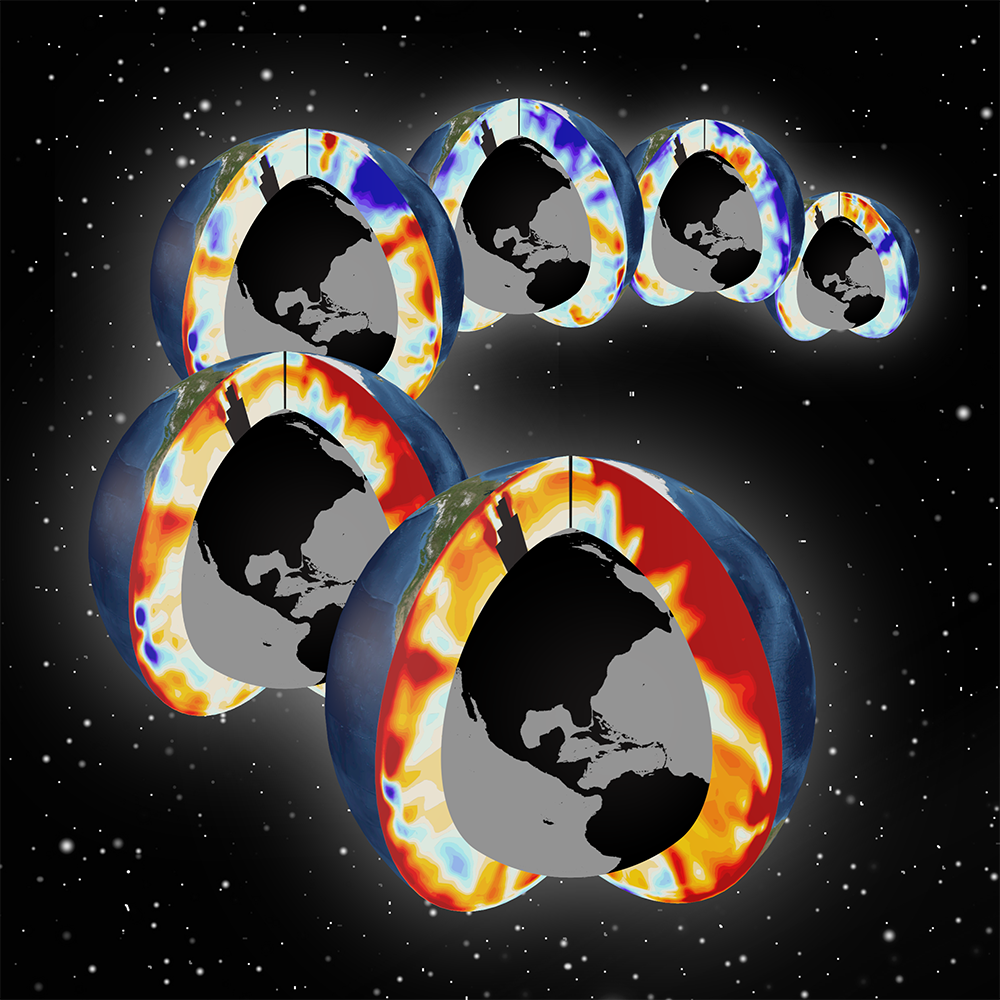

Pacific and Atlantic meridional sections showing upper-ocean warming for the past 6 decades, 1955-2011. (Photo: Timo Bremer/LLNL)

MCCARTHY: So, we talk a great deal about how much the surface of the Earth or the surface of the ocean is warming, and that’s what people look at when they look at a trend—the ups and downs from year to year—but over the last few decades now that we’ve had really good data from the deep ocean, we’ve seen that most of the warming that’s occurring is not in those surface measurements, it’s in the interior of the ocean. So 93 percent - is the best estimate - of the amount of warming that the Earth has experienced with the greenhouse gases we’ve added is in the deep ocean. So when we look at the surface signal of up one year, down the next year, up the next year, down...we’re looking at a very, very small part, and that’s why it’s important to look at these trends in the deep ocean.

MCCARTHY: And what this particular study shows is that in one area of the ocean, the South Pacific—so the Pacific Ocean’s the largest ocean. It covers a little over 40 percent, and more than half of that is south of the Equator. The South Pacific is a region that we have very, very sparse data. This paper uses a variety of approaches to now see whether or not our historic estimates of the heat content of that part of the deep ocean - and here I’m saying deep, but we’re talking about only to 2,000 meters, so 6,000 feet - that’s only half of the depth of that ocean, but we now have data for that upper half of vast areas of the ocean that before were poorly, poorly quantified.

A float mission composed of drifting at a shallow pressure level and then sinking to a deeper pressure level for profiling to the surface. (Photo: NOAA)

CURWOOD: Over the years, the computer models of the Earth’s climate have consistently underestimated the rate of change, how fast again the terrestrial area might be warming. To what extent does this new data make computer modeling more accurate?

MCCARTHY: Well, it makes the modeling, not necessarily more accurate, but it helps us understand where the various components are, that is, where they are in terms of contributing to the warming, and helps us understand what in the past had been talked about, imbalances or the missing heat. So the big mystery that still remains is: what’s happening even deeper than 2,000 meters, 6,000 feet, in other words, the other half of the deep ocean. And this is an area where now the data are really sparse. Some people say, you know, we know more about the surface of the moon than we do the deep ocean. We know more about Mars than we do parts of the deep ocean.

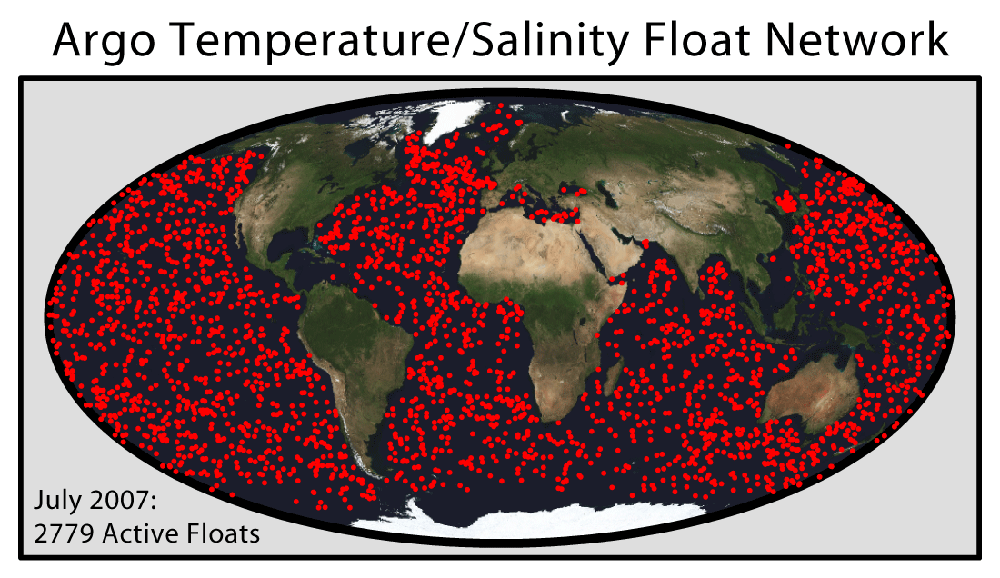

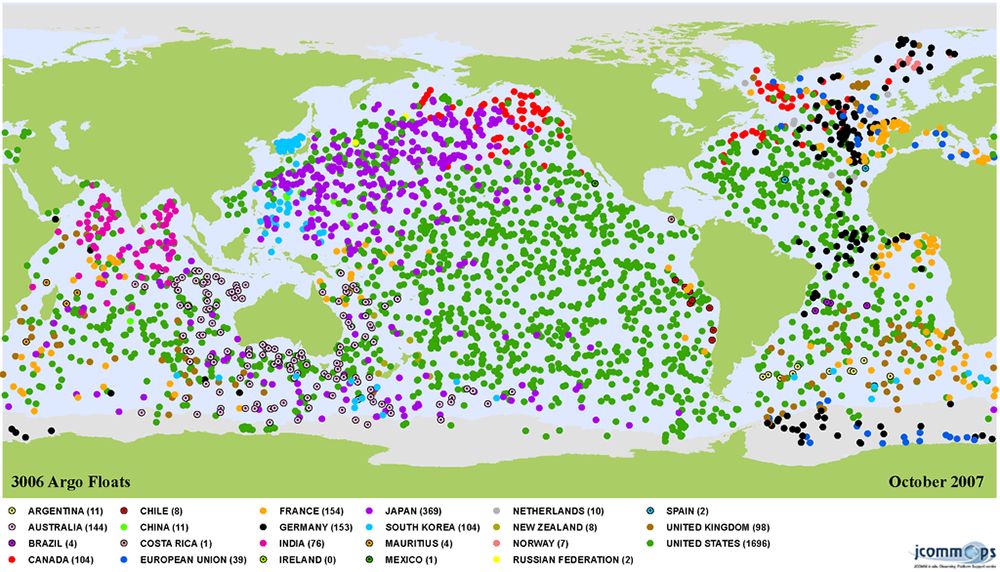

This map shows the distribution of the Argo float network, an internationally managed system of ~3000 free-floating temperature and salinity sensors deployed throughout the oceans. These sensors communicate via satellite, drift on ocean currents, and have the ability to submerge to a depth of ~2 km to create vertical profiles. (Photo: Dr. Robert A. Rohde; Wikimedia Commons)

MCCARTHY: So it’s a frustration for ocean scientists that the resources just haven’t been there to understand what’s happening in the deep ocean. So we have a really good data for the upper 2,000 meters, with the Argo array that had global coverage beginning a little over a decade ago, so they’re 3,500 of these floats, over two dozen nations participating in this really, very successful oceanographic effort. So when people begin to make calculations now about what’s happening in the deep ocean, without observations, we don’t have a really good way to reconcile or to confirm or refute some of those calculations.

CURWOOD: There was an article, recent article in Nature that said that we ought to ditch this two-degrees centigrade warming goal for the Earth for policy. What sense does that argument make to you?

Argo Float Network spans the globes oceans, but the majority of the buoys are in the Northern Hemisphere (Photo: Mathieu Belbeoch; CC-BY-SA-3.0)

MCCARTHY: It’s a very thoughtful critique by a couple of people who are very experienced in this area: Charlie Kennel and David Victor. And when they say we ought to ditch the two-degree, I think they’re saying two things: one is that we’re not doing a very good job in attaining that goal. It’s such a vague process that, having agreed to that, how we’re actually going to do it. And their argument is: “We’re not really making progress so we ought to be realistic about that.”

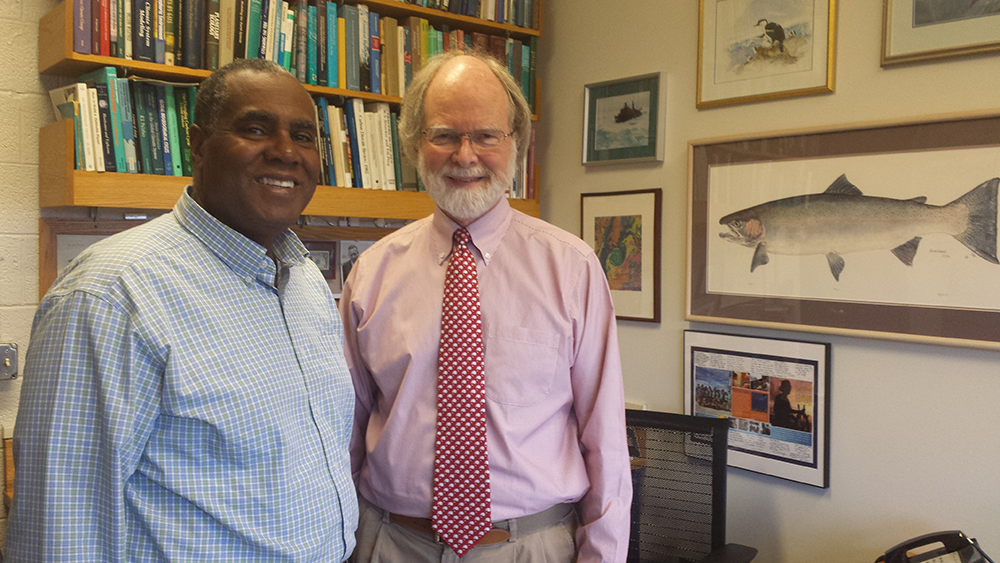

Host Steve Curwood with Harvard Professor of Biological Oceanography, James J. McCarthy, as he explains the Expendable Bathy Thermograph (XBT). These were deployed around the globe, but primarily in the Northern Hemisphere beginning in 1970. (Photo: Lauren Hinkel)

MCCARTHY: But they also point that the debate about whether these recent trends in surface temperatures indicate the Earth is not warming as rapidly as we thought or not—that’s a really poor indicator, that two degrees—and they think it would be better to develop some sort of composite index that would look at other vital signs, if you wish, of the planetary climate system such as the deep ocean, how rapidly is it warming, such as the loss of arctic ice. So I think there’s a lot of value to that argument, and I think partly it’s a wake up call. But if you look at those deep ocean numbers, it’s a very real thing. So I think it’s something we really need to think about.

Professor James J. McCarthy describes how the Expendable Bathy Thermograph drops a weighted sinker that records temperature data and transmits it. The copper wire snaps at a depth of about 700 feet and the torpedo-shaped part drops to the ocean floor. (Photo: Lauren Hinkel)

CURWOOD: James J. McCarthy is a Marine Scientist at Harvard University. Thanks so much, Professor.

MCCARTHY: Thank you, Steve.

Host Steve Curwood with Prof. James McCarthy in his Harvard office. (Photo: Lauren Hinkel)

Related links:

- Read Paul Durack and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s study “Quantifying underestimates of long-term upper-ocean warming"

- NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory published a complementary paper in Nature Climate Change: "Deep-ocean contribution to sea level and energy budget not detectable over the past decade"

- Photos and graphics from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory “Quantifying Underestimates of Long-term Upper-Ocean Warming”

- Watch a short video on how the Argo floats work

- Learn about the Argo ocean floats array Project

- More about the Expendable Bathy Thermographs (XBT) probes that were deployed prior to the Argo Project

- Paul Durack’s biography

- Professor James J. McCarthy’s site

Mercury in Coal Dust Poses Wetland Threat

Scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey gather samples near coal train tracks in the Columbia Gorge near Washougal, Washington. Little research has been done on how coal interacts with the environment. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

CURWOOD: Of course, coal is a big driver of the warming of the world and its oceans, and while we are using less of it here in the U.S. these days, we still plan to export more coal to Asia. That means transporting it by trains, as we’ve done for decades, but there’s very little research on the effects coal has on the environment when it escapes from coal hoppers bumping along the rails. With two large coal export terminals proposed for Washington State, a federal agency is hoping to add good science to the debate over the risks of coal train dust. From the public media collaborative EarthFix, Ashley Ahearn has our story.

AHEARN: This is the sound of wetland science.

[SLIDING, SPLASHING INTO WATER]

BLACK: I’m pulling a two-person inflatable kayak that I suspect weighs about 80 pounds by itself, and then there’s gear in it. And I’m old. [LAUGHS]

Scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey head into the marshes of the Steigerwald Wildlife Refuge near Washougal, Washington to learn how coal dust from trains might impact the environment. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

AHEARN: Bob Black is the lead researcher on a new study being done by the U.S. Geological Survey. The USGS is wading into the controversy over coal trains and coal terminals in the Northwest.

AHEARN: Black and his team are gathering samples from this stretch of marsh, sandwiched between the Columbia and train tracks, just across the river from Portland.

[TRAIN SQUEALING SOUNDS]

AHEARN: An orange BNSF engine squeals by a little more than 1,000 yards from the scientists as they prepare fish traps and other sampling gear.

AHEARN: Right now only one or two coal trains come through here per day, but if the proposed coal terminals are built in Longview and near Bellingham, Washington, that number could rise to more than 20 trains per day.

[SCIENTISTS TALKING, GEAR]

AHEARN: Black acknowledges that this is a tricky issue, but he says his job is to check all personal opinion at the door and just get down to the science.

BLACK: We have to be as unbiased as we possibly can be. So I understand people’s concern, but our role here is to try and see if the science supports those concerns or not.

[SWISH OF WATER]

AHEARN: Coal contains mercury, arsenic and other metals, but scientists don’t know whether those contaminants are easily released from the coal when it gets into the environment. So this team is gathering samples at two sites here – one closer to the tracks, and the other farther away. They’re looking for potential signs of coal pollution in the food chain – from fish to dragonfly larvae.

Right now, roughly one coal train per day travels along the Columbia River and north through Seattle to service a Canadian coal terminal, but that number could jump to more than 20 trains per day if terminals are built near Longview and Bellingham, WA. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

AHEARN: Collin Eagles-Smith looks pretty comfortable thigh-deep in thick, black mud. He’s an ecologist with the USGS, and an expert dragonfly larvae trapper.

EAGLES-SMITH: You can see it trying to bite me.

AHEARN: He holds one up to inspect before putting it into a plastic baggy to take back to the lab. It looks like something straight out of the Alien movies.

EAGLES-SMITH: These guys cling on to plant matter, and they kind of lie in wait. And then when a food item comes by, it kind of jumps out with its arms and grabs them.

AHEARN: Dragonfly larvae are voracious predators, and they live in the muck for several years before turning into adults. That means they have a lot of time to accumulate mercury, and then potentially transmit it up the food chain to the frogs, birds and fish that eat them.

[NET SOUNDS IN WATER]

Collin Eagles-Smith hunts for dragonfly larvae at Stiegerwald

Lake National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

AHEARN: Wetlands can be stinky places. Eagles-Smith says that rotten egg smell we associate with mucky spots like this one, is a sign that tiny organisms are doing their duty, breaking down organic material. And they might do the same thing for coal - releasing the mercury from the coal, into the food chain.

EAGLES-SMITH: I like to think of it as activating the mercury, and it makes it more biologically active, more toxic.

AHEARN: But the scientists don’t know for sure if that’s happening here. The USGS will detect any mercury in the dragonfly, fish and muck samples they gather today. Then they can examine the mercury’s isotopic fingerprint to try to figure out where the mercury came from.

AHEARN: It’s no easy task. Mercury can travel in air pollution for thousands of miles. Some research has traced mercury pollution in the U.S. to coal that was burned in Asia. But scientists want to know if coal trains that pass through wetlands like this one might serve as a sort of direct deposit of mercury pollution.

[BLACK TALKING]

AHEARN: Bob Black pauses between casting fish traps into the shallow water.

BLACK: There are multiple locations through the Northwest where tracks are near water, so it should be a concern, something to consider in more than in just a few locations.

AHEARN: Black says The USGS hopes to have results within the next six months. They’ll be sharing their findings with the state and federal agencies that are studying the environmental impacts of the two proposed coal terminals in the Northwest. I’m Ashley Ahearn in Washougal, Washington.

CURWOOD: Ashley reports for the public media collaborative, EarthFix.

Related links:

- Read more about coal dust’s impacts on wetlands in the pacific Northwest on EarthFix

- Hear more of Ashley Ahearn’s work on EarthFix

[MUSIC: Led Zeppelin from “Since I’ve Been Loving You” from II (Atlantic Records 1969)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: with its cities darkened by choking air pollution from coal, China turns to fracking for natural gas. We’ll have that story just ahead. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Brad Mehldau from “Exit Music (For A Film)” from Songs: Art of the Trio (Volume 3) (Warner Bros.1998)]

China's Energy Efficiency Program Still Promotes Global Warming

Beijing’s smog (Photo: Kevin Dooley; CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. China is the largest CO2 polluter on the planet, just ahead of the United States. And now the world’s most populous nation is pledging to cut the carbon intensity of its economy nearly in half by the end of the decade, by becoming more energy efficient. But Dabo Guan, an economist with the University of East Anglia says rapid growth in China means carbon emissions will still keep rising. Professor Guan joins us now from Harbin, China. Welcome to Living on Earth.

GUAN: Thank you. Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: So, in recent years, China’s been working hard to improve its energy efficiency, particularly its carbon efficiency. How successful has China been at this?

GUAN: Yes, China has made substantial achievements in reducing carbon intensities, but there are problems, of course, in terms of how or the way they’re reducing carbon intensity.

CURWOOD: And those problems are?

GUAN: Because the carbon intensity is not an absolute measure, it’s a relative measure, basically it’s CO2 divided by GDP, so essentially there’s two ways to reduce this figure. One way is to reduce CO2; the other way is to enlarge GDP. Reducing CO2 requires lots of technology improvements, and the technology spillovers, transfers, etc. It’s quite a relatively long and expensive way to do that. Most of the provinces in China, they actually adopt the second way, which is enlarge GDP to reduce carbon intensity. The way they do that, for example, they used to have a small, inefficient coal power plant. They closed down that and replaced it with a large, modern one. In that way, they achieved the efficiency improvements quite significantly, but on the other hand, it benefits local GDP.

Chinese coal workers (Photo: Bert van Dijk; CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let me see if I understand the problem. What you’re saying: If there’s a small, dirty inefficient coal plant, and it’s replaced by a much larger, but efficient coal plant that has much more carbon than the original small one, that that gets counted as a plus, under the math of looking at carbon intensity when in fact we're actually raising emissions.

GUAN: Exactly. During 2002 to 2009, Chinese sectors in terms of technology efficiency, they improved 10 percent, but the size of the electricity sectors increased about 10 times, so the overall economic carbon intensity has become, is largely offset by such carbon-intensive production.

CURWOOD: I gather that a lot of these big facilities were put up in accordance with lending from the provincial banks who very much like to do these big coal-fired power plants, which they see as surefire investment.

Despite efforts to reduce their carbon intensity, Chinese coal production has skyrocketed in recent years. (Photo: Plazak; CC 3.0)

GUAN: Yes.

CURWOOD: To what extent is the national government able to change the approach of those banks that’s investing in these huge coal-fired power plants and steel plants and such?

GUAN: Yes, the key reason for the regional governments, pushing the local banks to lend money to the developers to build those heavy industries, is because when you build that you actually create GDP, and the GDP, when they do the performance assessment through the individuals in terms of Chinese officials, GDP has just always come as the priority—always as the first criteria for measure, whether you are suitable to a promotion or not.

CURWOOD: So if I'm hearing you correctly, the demand for products isn't doing this as much as the concern by local officials that they hit the numbers for GDP growth.

Economics Professor Dabo Guan (Photo: University of East Anglia)

GUAN: Exactly.

CURWOOD: So unless this changes, carbon emissions are just going to keep going up and up and up.

GUAN: Well, China is the largest carbon emitter in the world. But to China, the concern is more air pollution and water pollution. You've probably heard that air quality issues in China this is so serious now. When you're dealing with air pollution, it actually creates a co-benefit for CO2 reduction. So therefore, I will say, China can make more effort, or could make some extra commitments other than carbon intensities, trying to have an absolute cap in some of the advanced regions and cities.

CURWOOD: Dabo Guan, is Professor of Economics at the University of East Anglia. He joined us on the line from Harbin, that’s in Yunnan, China. Thank you so much, Professor.

GUAN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Dabo Guan teaches at the University of East Anglia

- Read more about Professor Guan’s paper here

China's Great Frack Forward

Transporting coal down the Yangtze River in China. (Photo: BigStockPhoto)

CURWOOD: Well, as Dabo Guan says, air pollution in many Chinese cities is a public health crisis, with dangerous smog and particulates way beyond safe levels. The Chinese government has begun moving power plants away from population centers, and making massive investments in solar and wind power. And now, as co-authors Jaeah Lee and James West detail in the current issue of Mother Jones Magazine, China has put a lot of cleaner-burning natural gas in its five-year plan, and is looking to the U.S. for fracking technology. James West joined us on a line from his office in San Francisco.

WEST: China's getting involved in fracking by firstly, this kind of top-down approach. In their latest national plans, they have an aggressive goal to create a certain amount of shale gas by a certain year, by 2020. It's a really big goal, it's twice the rate of the way the U.S. first started their industry, so it's fast. They're really pushing for this to happen.

CURWOOD: I take it the attraction for China for shale gas is that when you burn it, it doesn't spit out the particulates that you got from coal.

Air pollution above the forbidden city, Beijing (Photo: bafac; Flickr 2.0)

WEST: That's exactly right. We saw coal plants in the dozens spewing out these particulate matters, the main cause of smog across China. Fracking causes far less of that, and so that is a huge appeal to the Chinese government right now. It could potentially have an enormous source of cleaner fuel, not just for this particulate matter that causes smog, but also for greenhouse gases. As we know, there's an ongoing debate about the level of greenhouse gases that fracking itself produces, and whether or not methane, which is a byproduct of the fracking process and can leak out of the pipes in the fracking process itself—that's a very potent greenhouse gas. And there's an ongoing debate about how potent and whether or not it's worse or better than CO2 emissions from coal burning. But at this point, the Chinese government is putting all its cards on the table and going, "We're going to play them all at once," and certainly this is one of them in the hopes that their huge reserves of it will potentially prove to be much cleaner than coal.

CURWOOD: And just how big are China's shale gas reserves?

WEST: They're bigger than in the U.S. They are the biggest in the world. They have two major shale gas basins in China, one is in the Sichuan province, which is, I guess famous in the rest of the world for its spicy food and its pandas…

CURWOOD: Indeed.

WEST: ...and also in the vast Northwest region of China, which is home to the Uighur minority. And they haven't begun fracking there so much because there’s quite a lot of political instability in that area and not a lot of water. So they're really focusing on the Sichuan basin. It's a remote farming providence, very poor, very rural, full of villages that have largely remained untouched by China's very rapid modernization.

CURWOOD: Now, hydraulic fracturing to get shale gas, to get natural gas, is super high tech—a lot of fancy equipment the United States was developed to make all that possible. How are the Chinese doing with the technological challenge here, and what role are U.S. companies playing in helping the Chinese extract natural gas through fracking?

U.S. natural gas companies have been meeting with Chinese officials and sharing fracking technology and expertise with China. (Photo: James West)

WEST: This part of the story is actually quite eye opening, I think, personally. We had exclusive access to this conference where we saw top-level Chinese officials interact with U.S. counterparts from the State Department, from trade, from commerce, these people who had providing entrées to the CEOs of Halliburton and Chevron and Exxon to really hammer out these deals between frackers in China and frackers in the U.S. They are talent-sharing, skills-sharing, performing the function, not only of providing money, but also expertise—and that's the thing that China so desperately needs. They don't know how to do it and are asking the U.S. to help. The shale reserves in China are deeper and more complex than the ones that provided the boom here in the United States. And so there's a few tricky things to iron out, and so, that expertise, they're counting on it, and the U.S. is giving it in spades.

CURWOOD: Now the power plant emissions regulations that the Obama administration is rolling out really favor natural gas here in the U.S. To what extent do you think that the administration, the White House, is trying to promote this industry at home and abroad?

A Chinese construction worker (Photo: James West)

WEST: Yeah, I think we've begun to see evidence that, particularly under the Hillary Clinton State Department, that this is something that the United States is directly exporting to foreign governments at this point. We saw the then U.S. Ambassador, Gary Locke, directly talking about the U.S. efforts to spread that technology around the world in particular to China in this case. So yeah, you're absolutely right. This is something that they have almost branded as U.S. know-how. The way we heard it described is, what's good for America in terms of business is also good for China in terms of learning, but also that an energy independent China is a secure China—one that stays within its borders potentially. One that doesn't have to look into the South China Sea, doesn't have to be a kind of aggressive geopolitical force in Southeast Asia. The way it was described to us is, that's a good thing for the United States as well.

CURWOOD: Now China has a water supply problem, a substantial water supply problem, so when you frack for natural gas you need water. How are they dealing with that?

James West, setting up his camera in China (Photo: Mimi Wong)

WEST: At the moment, there seems to be enough water in Sichuan province where we were, for the scale there right now. It's quite a fertile area. It feeds the Yangtze River basin. But really the main worry is not necessarily where the water is coming from in Sichuan, it's where the wastewater is going. We saw this fracking wastewater site that was 100 feet, maybe less, from a tributary of the Yangtze River, and you can imagine during a downpour all of that water going straight into the Yangtze River. And so you began to see this kind of capsule of a bigger problem. If they were to expand rapidly, which is their plan, then is this what we're going to see across the Yangtze River basin? And you can anticipate that's going to be a major headache for the entire area if they do get on top of it right now.

CURWOOD: What folks in Sichuan are concerned about water issues?

WEST: Yeah, we spoke to a number of people that were explicitly concerned about the water quality after the frackers had come in. Most all of them said that mysterious stuff started to come up in their water. And not only that, but their groundwater had begun to become depleted after the fracking industries had come in. We spoke to one woman who said that ever since they came in, set up the well, and left, they have no ground water whatsoever. They had to start carrying in water from a neighboring village.

CURWOOD: We have some audio of this woman talking about these water issues. What's her name Daijong Fu.

WEST: This is Daijong Fu. She's a local in Sichuan that we met outside of a gas well, and she says that the groundwater just hasn't been the same since the frackers left.

CURWOOD: Let's take a listen.

FU: [speaking in a Chinese dialect and translated] We can't even use the water to cook rice anymore. Now when the kids come back from the city, they bring us bottled water. We have to use boiled mineral water mixed with powdered milk to feed the kids. No water. So nothing we can do. People from the well site came often. They even brought boxes specifically to take water samples for testing, but there's been no results.

Dai Zhongfu, a woman from Sichuan Province, says her water has been contaminated by fracking. (Photo: James West)

CURWOOD: James, the other day, it seems like China is really in a bind here. We've got serious public health problems related to the particulates from firing coal, but fracking for natural gas is raising questions around water quality. It seems like they're between a rock and a hard place here.

WEST: Yeah, and you know this is what really scrambles everyone's ideas about how potentially easy progressing to renewable technologies could be in the west, or climate action in general in the west. I think when you go to China, it's such an environmental emergency, 70 percent of their energy comes from coal. They're the biggest consumer, the biggest producer of coal. And so, what do they do? It's a different algorithm to work through than what goes on here in the west. You can feel one way about fracking here, but I think you kind of have to feel a different way in China, and my personal opinion from reporting there is that I didn't really come away with a sense of, they should or they shouldn't, really. Are the U.S. companies playing an important role in making it the safest it could possibly be? Yes, but we know that in the states where they can take a shortcut they likely do. So in a country where everything is a shortcut, could it be a potential race to the bottom, you know? And I guess we don't have answers to that. We are sort of mapping out this sort of vibrantly new field of industry there. The locals don't know what's going to happen; the people doing it don't know what's going to happen. But all we know is that China has to do something and do it fast in order to prevent a bigger crisis from happening. And you know, the world is waiting to see. China is the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world, so we should be encouraged by their actions to embrace cleaner technology; we should also be vigilant about how they do it. And that was, I guess, my main take-out from the trip: be vigilant, keep watching, be confident but also be very wary.

CURWOOD: James West is a writer for Mother Jones and a producer for Climate Desk. Thanks for taking the time with us today, James.

WEST: My pleasure. Anytime.

Related links:

- Check out the original story here. Produced by Jaeah Lee and James West

- Read more from James West at Mother Jones

China's Online Environmental Activism

Environmental activist Zhu Qing (Photo: Allison Griner)

CURWOOD: Student-led protests have recently clogged the streets of Hong Kong, demanding that China live up to its “one nation, two systems” pledge, and allow more democracy in the former British territory. As we record this, the authorities haven’t cracked down on these demonstrations, as they typically do on the mainland of the People’s Republic. But on the mainland, environmental protests often receive more lenient treatment, and despite censorship, eco-activists have become adept at using social media to organize their activities. Reporter Allison Griner has our story from the streets of Beijing.

GRINER: Lu Tianyi weaves her way through Beijing’s bustling South Railway Station. She’s trying to catch a morning train to another metropolis, Tianjin, where she’ll meet a colleague she rarely ever sees in person. Lu is part of an environmental movement that’s increasingly being organized online, despite the threat of censorship by the Chinese government.

[TYPING ON KEYBOARD]

Reporter Allison Griner in front of an aqueduct in France. (Photo: Courtesy of Allison Griner)

GRINER: China has the world’s largest number of Internet users—and that’s with only 44 percent of China’s citizens online. Even Chinese social media dwarfs its counterparts overseas. The Chinese Twitter, Sina Weibo, tallies up to 281 million active users. The actual Twitter only racks up 232 million.

[ERHU MUSIC PLAYING]

GRINER: The Chinese environmental movement is trying to use all that online people power to its advantage. Lu works for one of China’s most influential online voices, a journalist-turned-cyberspace entrepreneur named Deng Fei. Over his lifetime, Deng has witnessed drastic changes to China's environment even in his own hometown.

DENG: [Deng speaking, translated] My hometown is a delicate town beside Dongting Lake in Hunan province. Back then the water was relatively clean, but that's changed with the population grown and urbanization. The last time I went back to see the river in my hometown, it was very dirty. That's because of people who live by the river directly discharge human excrement into the river.

GRINER: A former investigative reporter, Deng decided to find out more about China's water pollution. During the 2013 Lunar New Year, Deng posted a simple question on Weibo: How is the river in your hometown? His online followers responded with dozens of photos and stories about pollution being poured into their local waterways.

Woman on the street in Beijing (Photo: Allison Griner)

GRINER: This ability to speak out about the pollution, is something relatively new to the Chinese people, Deng says. And it's all thanks to social media.

DENG: [Deng speaking, translated] You might say that Weibo has been God's best gift to the Chinese people. For the first time ever, our freedom of speech has been expanded so much that all Chinese people have the right to speak freely. Basically, it’s pushing forward a new era.

[SUBWAY SOUNDS]

GRINER: As we roll into Tianjin, we meet one of Deng’s partners in the campaign against water pollution. His name is Zhu Qing, and he's a 22-year-old representative from the environmental NGO Green Collar. He’s standing on the wind-swept shores of two stagnant, brown canals that flow into one Tianjin's main rivers.

[ZHU SPEAKING]

GRINER: China’s rivers are divided into five categories, says Zhu. Level one rivers are the best. They’re so clean you can drink from them, but level five rivers? Well, they’re the worst. Their water is so toxic that you can’t even use it to water plants.

ZHU: This kind of river is the fifth level. This kind of pollution is too serious because it makes the underground water polluted, so the people get cancer.

Lu Tianyi on a train (Photo: Allison Griner)

GRINER: That’s right, cancer. It was only in 2013 that the Chinese government finally admitted its water pollution had gotten so bad that it was causing cancer in some rural villages. The Chinese government maintains a firm grip on its public image; that's why social media platforms like Weibo are monitored and censored. So I asked Zhu: Is it scary to use Weibo for activism?

ZHU: It’s not too scary for me. [LAUGHS]

GRINER: Zhu has heard of environmentalists being beaten up, but he feels protected by social media and the public outrage it can mobilize. And he also says that social media is helping to connect environmentalists with government officials, whom they otherwise couldn't have a dialogue with.

ZHU: Because of our social media, the government said, “Okay, we need to talk, and we need to take action.” They want to talk with you, and so this is the most accomplishment made by the social media.

A river in Tianjin, China (Photo: Allison Griner)

GRINER: Social media is also connecting young environmental groups like the one Zhu belongs to, to donors and entrepreneurs like Deng Fei. With the money brought in by social media campaigns, Zhu's NGO can finally rent space to organize and plan more outreach efforts.

ZHU: People can get together to get some new ideas about how to solve these kinds of problems, and at the same time, the government will feel pressure and so they will take actions.

[TRAFFIC]

GRINER: As we leave Zhu and the polluted waterway, Lu Tianyi, Deng Fei’s representative on our trip, muses about her dreams for China's environment.

[LU SPEAKING CHINESE]

GRINER: She works with Deng in hopes that the next generation won’t be plagued by cancerous water or smoggy skies. No, she’s looking forward to a cleaner environment in China’s future. And she tells us, she’s confident that the bonds of social media are the first step for change.

GRINER: For Living on Earth, this is Allison Griner

[BEIJING STREET MUSIC]

CURWOOD: The International Reporting Program at the University of British Columbia supported Allison’s work. She recorded the music on the erhu on the streets of Beijing.

Related link:

Allison Griner’s website

CURWOOD: Coming up: Years of Living Dangerously with Hollywood producer and director James Cameron. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from United Technologies a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC building and industrial systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with Brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Björk: “Frosti” from Vespertine (One Little Indian 2001)]

Beyond the Headlines

Beach erosion is a consequence of the worldwide building boom. Sand is required to make concrete, and its mining is happening faster than beaches can naturally be replenished. (Photo: Sarah Kim; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Time now to catch up with Peter Dykstra. He’s the publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. He’s on the line from Conyers Georgia. Hey, Peter, what did you turn up beyond the headlines today?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. Y’know, we’ve talked here in the past about the sand wars associated with the boom in fracking. Since you need silica for the fracking process, places like Wisconsin and South Dakota, and Texas have seen their own boom in sand mining, but elsewhere in the world, there’s something of a sand crime wave going on.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, I mean, sand has got to be one of the most cheap, common resources out there. What makes it valuable enough to cause a sand crime wave?

DYKSTRA: In places like China and Brazil and India, there’s an unprecedented building boom. That building boom needs an unprecedented amount of concrete, and to make concrete, you need lots and lots of sand. The UN Environment Programme says we’re using 40 billion tons of sand and gravel every year, most of it for concrete, and sand is just as subject to simple economic laws as anything else. Demand goes up, the price goes up, and then people steal beaches.

CURWOOD: Whoa, and when they do, it’s not like we’re replacing those 40 billion tons of sand and gravel we’re taking.

DYKSTRA: Right, the German Magazine Der Spiegel covered this in depth. They reported on a situation in the Cape Verde Islands, where the beach sand is disappearing one bucket at a time. In one sadly ironic case, there was a town there, once protected by a wide beach, and now prone to high-tide floods. So, of course, they built a seawall.

CURWOOD: Out of concrete, I presume, Peter? Like they’re doing elsewhere because of rising sea levels?

DYKSTRA: Correct. So, let’s move off the sand-crime beat and on to some good news.

Chicago’s fleet of 600 garbage trucks now includes 20 electric trucks. (Photo: Arvell Dorsey Jr.; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Oh, good. Be my guest.

DYKSTRA: The garbage trucks that haul our household environmental messes away also leave a few environmental problems behind. Traditionally, garbage trucks are diesel trucks, belching smoke. Sometimes not doing much better than a mile per gallon of fuel, and making a tremendous racket that, depending on your garbage route, might be outside your door at four in the morning. But Chicago’s city fleet of garbage trucks is getting a little quieter with emissions-free, almost noiseless electric trucks.

CURWOOD: Silent, smoke-free trash pickup? How is this going to work?

DYKSTRA: Some have been in use elsewhere, but these would be the first electric garbage trucks in North America. Chicago’s conversion is only partial, initially 20 of their 600 trucks, and the electric ones cost more to buy, but it’s hoped they’ll save fuel and maintenance costs in the long run.

CURWOOD: Well, perhaps with some turbines we could have wind-powered garbage trucks in the Windy City, huh? OK, Peter, take us back through the annals of environmental history now. What’s on the calendar this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, if this is the age of government by soundbites, 22 years ago this week, we heard a soundbite for the ages and it came from H. Ross Perot, maverick businessman and really the most successful third-party Presidential candidate this country has seen in recent years. In a Presidential debate, Perot predicted that NAFTA, the free-trade agreement between Mexico, the U.S. and Canada, would result in – and here’s my best Ross Perot imitation – “A giant sucking sound.” That was his way of saying that free trade would pull American jobs to low-wage workplaces in Mexico.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)’s encouraged industrial-scale farming in Mexico, which ended up displacing small farmers. (Photo: CJ Buckwalter; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: And critics also said it would hurt environmental enforcement. How does it all look 22 years later, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Not so good. A report by nonprofit groups in Canada, Mexico, and the US, released earlier this year for the 20th anniversary of NAFTA taking effect, said the treaty is every bit the environmental disaster that was predicted. The agreement helped enable Canada’s single-minded pursuit of tar sands oil and the resulting Keystone pipeline controversy in the U.S., and in Mexico, NAFTA’s helped build huge mining projects and industrial-scale, pesticide-intensive farming.

CURWOOD: Well, so that’s the environmental side, but with other trade agreements taking hold around the world, how did NAFTA help in terms of economics?

DYKSTRA: NAFTA’s net economic impact has helped the bottom lines of Canada and Mexico, but at the expense of the U.S. The Census Bureau says the U.S. ran a $54 billion dollar trade deficit with Mexico, $31 billion with Canada last year. Communities throughout the so-called Rust Belt of the U.S. continue to lose jobs and struggle and wither, and here’s one of the oddest unintended consequences of NAFTA: All those industrial-scale farms in Mexico? They displaced small farmers, and many of those small farmers went north looking for work. And they became part of what is often called America’s immigration crisis. How’s that for full circle?

CURWOOD: Well, you got me scratching my head, Peter. Peter Dykstra is publisher of Environmental Health News – that’s EHN.org – and TheDailyClimate.org. Thanks so much, Peter. Talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: Thank you, Steve. We'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Fracking drives demand for sand

- Sand crime wave

- North America's first electric garbage trucks

- NAFTA: 20 Years of Costs to Communities and the Environment

- Trade in Goods with Mexico

- Trade in Goods with Canada

Years of Living Dangerously

Executive Producer James Cameron. (Photo: The Years Project/SHOWTIME)

[SOUNDTRACK TO TV SERIES, YEARS OF LIVING DANGEROUSLY]

CURWOOD: The cable TV series “Years of Living Dangerously,” won a 2014 Emmy for outstanding nonfiction. It’s a high-profile, highly-produced and highly-praised investigation into the impacts of climate change worldwide, hosted by respected journalists such as Leslie Stahl, and Tom Friedman, and celebrity correspondents that include actors Harrison Ford, Don Cheadle and Matt Damon. James Cameron is an executive producer; he’s perhaps better known for blockbuster films such as Titanic and Avatar. This series first aired on Showtime – a premium cable channel, which limited its audience. Now though, it’s out on DVD, and iTunes, and James Cameron joins us by phone from Los Angeles. Welcome to Living on Earth.

CAMERON: Hey, Steve, thanks for having me on.

CURWOOD: So tell us about when climate change became an important issue for you?

CAMERON: I think pretty much as soon as I first started reading about it, going back 15, 20 years, and just the kind of growing awareness that there were all these growing environmental problems and climate change was one of them. And it began to emerge, I think, as the preeminent one that affected all the other systems and, you know, all of the other aspects of the ocean, the terrestrial ecosystems and then it came into a kind of preeminent focus for me. This would've been, I don't know, five, six, seven years ago.

CURWOOD: So, let's turn to the production of the “Years of Living Dangerously”. Tell me, how does using celebrities as the correspondents in this series help communicate better, than say using someone boring like a no-name journalist?

A palm oil plantation in Indonesia. The palm oil industry in Indonesia is closley linked to deforestation. (Photo: Achmad Rabin Taim; Flickr CC)

CAMERON: [LAUGHS] Well, we wanted to reach beyond just preaching to the choir. Documentaries in general, and certainly anything on the environment, tend to not be very effective in getting out there to people who may be skeptical or disinterested. Obviously the climate crisis affects us all across all political boundaries, and so we want to reach everybody, which is a lofty goal and one that’s probably not really attainable. But we thought how can we, what kind of hooks can we use to make good compelling television and also to get people to watch it. And so, the idea of incorporating, you know, Hollywood celebrities and other music celebrities and so on, sports, into this was brought to me by Joel Bach and David Gelber, the originators of the series, and I was skeptical at first. I thought, you know, people shouldn't listen to celebrities; you know, their lines are written down for them. But Joel and David said, “No, no, we’re not going to put them in as talking heads, as supposed experts, because they’re not climate experts. Let's have them be concerned citizens—curious and wanting answers and with the kind of compassion that actors can get to in dealing with human issues. And so let's have them roll their sleeves up and go out there into the field and then see what's happening to people right now,” and I thought OK that makes sense.

CURWOOD: What were you surprised to learn or see when you were making this series?

CAMERON: Well, I wasn’t surprised by the horror of what’s happening out there because I knew the facts going into it. I was surprised at how effective our celebrity journalists were at getting great stories out of people on the ground out there, you know, such as the minister in Indonesia when Harrison Ford confronted him.

Actor Harrison Ford meets with the president of Indonesia, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. (Photo: The Years Project/SHOWTIME)

[TV SERIES CLIP OF FORD AND HASAN]

FORD: Finally, I’m meeting the forestry minister. I have a lot of questions. We were in Tesso Nilo.

HASAN: Mmmm, Tesso Nilo. [LAUGHS] OK.

FORD: National park. It's not funny.

HASAN: Yeah.

FORD: It's not funny.

FORD: Only 18 percent of it remains. We saw it: There are new roads, new illegal roads. Forests cut. Trees lying on the ground, burnt where they fell. It's devastating. It’s heartbreaking to see it.

CAMERON: You know, it’s pretty strong television, and the thing that I think that Joel and David did deliver was good investigative journalism and really strong compelling TV.

CURWOOD: So Jim, what other places do you think a celebrity really made a difference in what you were able to get in terms of a response?

CAMERON: I think in every segment. I think in every segment they make a difference both in the viewer’s level of interest and the number of people that show up. And I think they made a difference in situ in the dialogues that they were having. Some other journalists might not have gotten that interview with that minister in Indonesia, and I think we should stress here because we've been talking celebrity, celebrity, celebrity, we also had Tom Friedman and Leslie Stahl and Mark Bittman and Chris Hayes and other solid journalists as well. This wasn't all just celebrity TV, but I think, you know in terms of the effectiveness of the show, when you’ve got Don Cheadle tearing up hearing the story of the people that he is talking to and you feel his compassion for them, it can't help but evoke compassion on the part of the viewer.

Actor Don Cheadle sits on the front porch of Nelly Montez, a resident of Plainview, Texas who lost her job at a Cargill meatpacking factory. The cattle industry was hit hard by prolonged drought in Texas. (Photo: The Years Project/SHOWTIME)

CURWOOD: Let’s play a bit of Don Cheadle here.

[CHEADLE CLIP FROM YEARS OF LIVING DANGEROUSLY]

CHEADLE: In a lot of the country something like a drought is seen as an Act of God or part of an natural cycle. But where I live in Los Angeles, it seems like any kind of extreme weather gets blamed on climate change. Sometimes it feels like we live in two different countries. I want to know what the truth is about this drought, and if it’s possible for these two sides to talk to each other. So, I'm heading to Texas to find out.

CAMERON: And I think that's what this is all about. Climate change is going to affect everybody on the planet, but it's going to affect a lot of poor people, a lot of farmers, a lot of people are going to have their lives hit a lot harder than people who are sheltered in urban environments. And I think that part of what people need to do to really confront this challenge is to open up and be compassionate for the people that are going to be on the frontlines of this crisis in the future.

CURWOOD: How does your awareness of the climate emergency, that so many environmental changes that threaten us now—how does that affect your work and the craft of making films? What do you do, for example, to reduce the carbon footprint of the kind work you do?

CAMERON: Well, I’m making three sequels to Avatar right now, which any individual one of them is a mega-production and we’re doing three of them together as one big production, and we’re operating out of a studio in Manhattan Beach here in Los Angeles. And we took the sound stages and we put 1 megawatt solar power-generating station essentially on the roof, so we will be net carbon-neutral in all of our production activities here in terms of power consumption, so we've took the initiative to essentially generate our own power. And, you know, we'll run a very green set and that sort of thing; so that’s the kind of thing that you can do to take a stand as a businessperson. And I try to live my life as green as I possibly can. My food carbon footprint is very low because I live on a 100 percent plant-based diet. I think you have to lead by example, you know, you can't just be spouting off and I think that's where celebrities really trip themselves up is when they spout off about a problem then they go live a profligate life.

Don Cheadle speaking with Prof. Katharine Hayhoe and Rev. Andrew Farley at their kitchen table. Prof. Hayhoe is an Evangelical Christian and an associate professor at Texas Tech University and, together with Rev. Farley works to bridge the gap between faith and science when it comes to climate change. (Photo: The Years Project/SHOWTIME)

CURWOOD: Sun-powered 3-D film, huh? [LAUGHS]

CAMERON: Yup. We’re solar-powered.

CURWOOD: So what are you thinking about in terms of putting say, a Cli-Fi movie in your future?

CAMERON: [LAUGHS] I don’t even know what that is. What did you call it?

CURWOOD: A Cli-Fi. You know, climate fiction movie.

CAMERON: Oh, Cli-Fi! Yeah, sure! Well, I mean, the Avatar sequels are about essentially the future of humanity and the future of life on Pandora and how those two are co-mingled, so you know, what's happening on the Earth 150 years from now is very much part of that story. And of course, climate dominates that, climate and resource depletion and so on; so that'll be part of it.

CURWOOD: Jim Cameron is one of the Executive Producers of “Years of Living Dangerously”. Jim, thanks so much for taking time with us today.

CAMERON: I appreciate it.

Related links:

- Where to watch ‘Years of Living Dangerously’

- A WWF report on deforestation in Tesso Nilo National Park

- James Cameron’s IMDB profile

[MUSIC: The Stranglers “Golden Brown” from La Folie (Liberty 1981)]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, a surprising musical duo - a clarinet and a whale.

[CLARINET AND WHALE SOUNDS]

ROTHENBERG: This is a kind of surprising moment where the whale showed some interest. So at that moment you feel like ah, maybe something's going on here. Maybe there's a sense of getting through to another species through music.

CURWOOD: Getting in tune with an interspecies jam. That's next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Sharif “Shiraz” from Putumayo Presents Sahara Lounge (Putumayo 2004)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of our team. Our show was engineered by James Curwood with help from Karlyn Daigle. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and please like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet. And Gildmann Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth