October 17, 2014

Air Date: October 17, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Companies Pulling Out of Canadian Tar Sands Oil

View the page for this story

With crude prices sharply down and the future of the Keystone XL pipeline in doubt, energy companies are dubious about investing in oil from the Alberta Tar Sands. OnEarth writer Brian Palmer discusses the problems facing the industry with host Steve Curwood. (08:25)

Methane Hotspot Seen from Space

View the page for this story

Using satellite data, scientists at NASA and the University of Michigan found a spike of methane over the Four Corners region of the United States. Host Steve Curwood talks with Christian Frankenberg of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory about the unexpected finding and its likely source. (05:25)

Cap and Trade Heats Up Pennsylvania Gubernatorial Race

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

The EPA’s proposed new power plant rules mean states must cut carbon dioxide emissions sharply by 2030, but Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidates disagree on how to do it. The Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports that joining the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative would help meet these goals, but that idea faces pushback from conservatives and PA’s large coal power industry. (04:40)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells us about a scathing report about the Canadian government’s environmental shortfalls written by the Canadian government, the cash value of clean water and the invention of nylon stockings.( (04:45)

Controversial Japanese Whaling

View the page for this story

There’s a global moratorium on commercial whaling, but Japan continues to kill thousands under the guise of “research”. Host Steve Curwood discusses Japan’s motives for this continued flouting of international rules with Dr. Phillip Clapham of NOAA’s National Marine Mammal Laboratory. (07:05)

.png)

Life For A Humpback Whale

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Mark Seth Lender heads out to sea, and in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary he watches a humpback whales and her calf as they doze in the calm at the surface. (03:00)

A Man, His Clarinet and Nature’s Singers

View the page for this story

David Rothenberg teaches music and philosophy at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. And he takes his clarinet, and plays along to and with birds, bugs and whales. He talks with Steve Curwood about his music, why creatures sing, and the rare moments of interspecies harmony he’s enjoyed. (13:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Brian Palmer, Christian Frankenberg, Phillip Clapham, David Rothenberg

REPORTERS: Julie Grant, Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender,

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. As the price of oil falls, energy companies are souring on Canadian tar sands oil, and getting it to market is part of the problem.

PALMER: It costs about $25 dollars per barrel to move tar sands crude from Alberta by rail to the Gulf of Mexico. If they had a pipeline, say something like the Keystone XL pipeline, they could cut that price from $25 down to $9 dollars. That’s a huge difference.

CURWOOD: It all puts tar sands mining in doubt. Also, an unlikely musical duo - a clarinet and a whale.

[MUSIC - ROTHENBERG “WHALE MUSIC”, SOLO CLARINET AND WHALE]

ROTHENBERG: This is a kind of surprising moment where the whale showed some interest, and so at that moment you feel like, ah, maybe something's going on here. Maybe there's a sense of getting through to another species through music.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

Companies Pulling Out of Canadian Tar Sands Oil

A tar sands mining operation in Alberta (Photo: C. Campbell, Palbina Institute; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The price of oil has been plummeting, down some 25 percent since June, and as we record this show, the price per barrel is near $80 dollars. Motorists and freight haulers see this as good news, but cheap oil encourages consumption, and over the long term that’s not such good news when it comes to cutting global warming gas emissions. Still, opponents of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline to carry tar sands oil to market from Alberta, Canada are seeing a benefit from the slump in oil prices, which makes it harder to make a profit. Uncertainty over Keystone and questionable returns recently prompted the Norwegian oil giant Statoil to halt its tar sands plans. Brian Palmer, a writer for OnEarth Magazine, has been following these developments. Welcome to Living on Earth.

PALMER: Thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: Brian, tell me, why did StatOil pull out of tar sands?

PALMER: Well, there's the kind of corporate press release, and then there is a kind of a lot of reasons kind of behind it. They did specifically mention changing market conditions and limited pipeline access, and what limited pipeline access means in corporate speak is the lack of the Keystone pipeline. The Keystone XL pipeline is crucial to tar sands projects in northern Alberta becoming profitable.

Pollution from industrial development in the Tar Sands region of Alberta (Photo: Kris Krüg; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, but Keystone is still on the table. It hasn't been taken completely off the table.

PALMER: That's true, but they need to do their long-term planning. As of a couple of years ago, I think most of the energy executives thought of the Keystone pipeline as something that had been postponed for political reasons, but once we kind of got out of election season, to the extent we have a non-election season any more, it would be approved. And we would kind of move forward no matter who was is in the White House. But environmentalists have been so successful in postponing it that a lot of oil companies are now worried that it's never going to happen, and if it's never going to happen, making a long-term commitment to a tar sands project is a kind of iffy proposition.

CURWOOD: Now, we're in the middle of a precipitous decline in price of crude oil. As we're recording this, the price of crude is down $81 dollars a barrel. How does that impact the viability of tar sands oil?

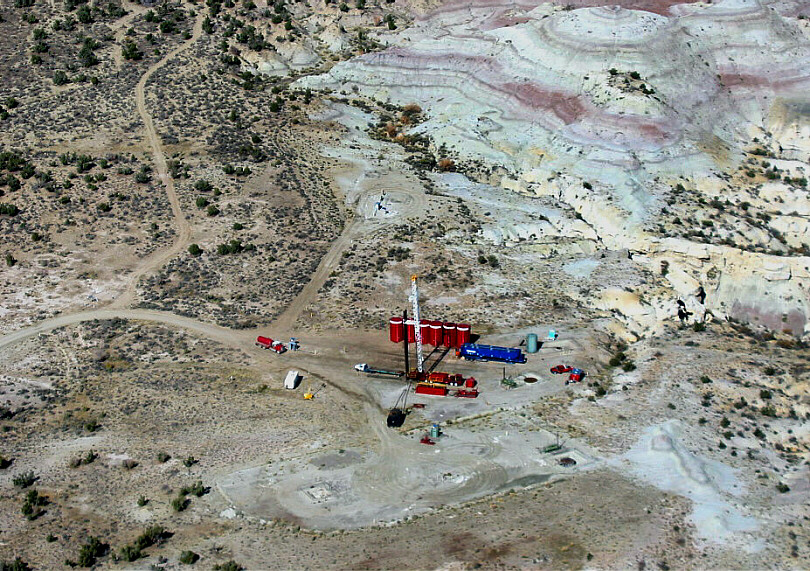

Right now, much oil from Alberta is being transported to markets by train. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

PALMER: So, to understand this you need a bit of background. Tar sands oil is a kind of a cheap low-quality version of crude oil that comes from a very specific and remote location. Extracting tar sands is nothing like drilling for oil; it's much more like mining. So you need to move huge amounts of equipment out there to get the tar sands out of the ground. You need more equipment to separate the bitumen, which is the stuff that actually makes oil, from the sand and clay that it's stuck in, and then you need even more equipment to cook that down and turn it into something that vaguely resembles crude oil. When all of that is done, you still have to get the stuff to a refinery.

There are limited places that are refining oil in North America right now. The two best places to ship crude oil from Alberta are probably the upper mid-western United States and the Gulf of Mexico, and getting it there is a challenge. As of right now, it costs about $25 dollars per barrel to move tar sands crude from Alberta by rail to the Gulf of Mexico. If they had a pipeline, say, something like the Keystone XL pipeline, they could cut that price from $25 down to $9 dollars. That’s a huge difference. Now, because tar sands, as I mentioned, is a much lower quality version of oil, of crude oil, it sells at a discount, something like $20 to $30 dollars less than conventional crude. So with conventional crude in the 80s, tar sands crude more like in the 60s, maybe even a little bit less than that. If you can only get something like $60 to $65 dollars for your barrel of oil, having to pitch in an extra $15 to $20 dollars to move it by rail right now, rather than pipeline, will turn a marginally profitable business into a completely unprofitable business and that's scaring oil producers off of tar sands projects right now.

Getting oil out of tar sands bitumen is expensive. Brian Palmer says it could be called oil mining. (Photo: Julia Kilpatrick, the Pembina Institute; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So this delay then, on the Keystone XL pipeline decision from President Obama, is essentially making the difference to the economies of this industry up in Alberta.

PALMER: Yes, and there are several factors. As you mentioned, the price of oil has dropped. The cost of labor has risen because Northern Alberta is like the kind of place that John Denver sang about - it is very, very remote. Getting people to move there costs money, and when you want to expand, you're trying to convince more and more people who are not that enthusiastic about moving there to go, you need to offer them higher and higher salaries, so labor costs are going up. So, there are a variety of factors, but there's great evidence to support the idea that the Keystone pipeline is the kind of difference between having new tar sands projects and not having new tar sands projects.

Without a major pipeline like the Keystone XL, expanding tar sands projects in Alberta is a risky venture. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: Now, there's been a debate about just how important Keystone XL pipeline is to getting tar sands oil. The folks who are opposed say it is essential. Industry says that the oil is going to get to port either way. How do you think the StatOil decision influences that debate?

PALMER: Well, so the StatOil decision is just one of many. Shell has canceled projects recently. The French energy company Total, SunCor Energy of Canada, they've all killed tar sands projects in the last year, and those cancellations have cost billions of dollars. What they're looking at is not the current state of things. They are looking into the future. There was an article in Politico quoting a lot of energy executives talking about how the delays of Keystone are sort of irrelevant, quoting a lot of numbers about how much Canadian oil is coming into the United States. But the issue is not expansion up until now. It's future expansions. So think of tar sands projects as being something like a freight train. It takes a lot of work to get one going, but once they're going, it's very hard to stop them. Once you’ve put, tens of millions, hundreds of millions of dollars into starting a tar sands mine, you're not going to shut it down because you've already put the money in.

Oil processing facilities at Fort McMurray, Alberta (Photo: Kris Krüg; CC BY 2.0)

PALMER: The problem is building new mines. If you're going to invest lots and lots of money, and you're an oil executive and you want to invest in a project that's going to take 30 years, but you have no reason to believe it's ever going to become profitable because you don't have a pipeline, that's going to scare you off, and you're going to have a hard time convincing your shareholders that's a good idea. So these other kind of alternatives: rail is a terrible kind of alternative. They want to expand another pipeline called the Alberta Clipper - that's encountering resistance. That's going nowhere. They just don't have a lot of options right now. They barely have enough to handle the tar sand oil that they have, and the idea of expanding the industry just seems like a complete nonstarter right now.

CURWOOD: So, looks like the Harper government is pushing to convert an existing gas pipeline that goes east across nearly every province in Canada to take oil from Alberta, to take that tar sands oil to refineries. What do you make of that?

PALMER: So the Energy East pipeline is sort of a Canadian version of Keystone XL, and it's getting the same reaction in Canada that Keystone XL got in the United States. Once it became a serious issue, lots of Canadian environmental groups started raising a fuss about it for good reason.

Writer Brian Palmer of OnEarth Magazine (Photo: Brian Palmer)

CURWOOD: Yeah, we saw that in Montréal Gazette reported that some 2,000 people showed up at a town of 2,000 to protest the Energy East pipeline. Doesn't seem like it's terribly popular in Québec anyway.

PALMER: That's pretty good turnout, I'd say.

CURWOOD: So how concerned are the shareholders of these major companies that these delays are going to go on forever?

PALMER: That's a good question. I think the flurry of articles we're seeing recently, talking about Keystone as no longer that important to oil companies, is an indication of worry in the boardrooms. If you own stock in an oil company that invests in tar sands and has an existing project and you see all these cancellations, you're starting to think why are we so heavily invested in tar sands when no one else wants to get into this business? And so I think what's maybe going on with a lot of these new articles and energy executives confidently talking about a new pipeline access like Energy East or Alberta Clipper or other pipelines, that what's going on is that's a message they're sending their shareholders saying, "Don't worry. There's going to be pipeline access. We're not throwing money down into a pit quite literally. This is going to work out in the end. You just have to stick with us through this and we'll make sure everything is OK.”

CURWOOD: And they're speaking the truth?

PALMER: [LAUGHS] Only time will tell. It doesn't look good right now if things continue as they are.

CURWOOD: Brian Palmer is a writer for OnEarth Magazine, a publication of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

PALMER: Brian, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

CURWOOD: Thanks for having me, Steve.

Related link:

Read Brian Palmer’s article in OnEarth magazine

[MUSIC: Caroline Cotter from “Champagne” from Il Est Juane]

Methane Hotspot Seen from Space

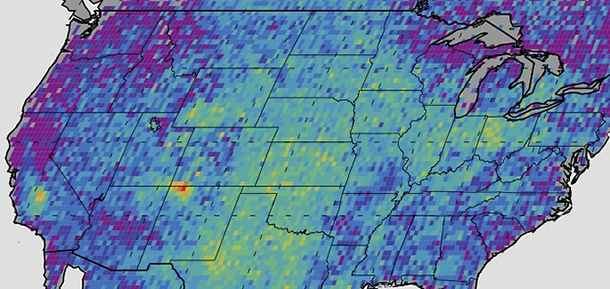

The methane hotspot in the Four Corners region is highly concentrated over a relatively small area – so it lights up much brighter than any other area in the U.S. on an image produced by the study. (Photo: NASA; CC government work)

CURWOOD: The states of Arizona, Utah, New Mexico and Colorado come together at Four Corners, and that is where NASA says there’s a huge spike in emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas, methane. NASA and University of Michigan scientists analyzed satellite data from 2003 to 2009, and a map of their results shows a bright red spot at the Four Corners, which is most likely related to coal bed methane extraction there, as it predates the boom in shale gas fracking. The satellite methane numbers are much higher than EPA estimates that rely on data from towers and airplanes. Christian Frankenberg is a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena and a co-author of the new study, which was published in Geophysical Research Letters. Christian Frankenberg, welcome to Living on Earth.

FRANKENBERG: Thank you for having me here.

CURWOOD: So, to start, how did you gather this data?

FRANKENBERG: We collected it from a European satellite called SCIAMACHY. In the paper, we looked at data from 2003 to 2009.

The San Juan Basin, in the Four Corners region, is the most productive coal bed methane basin in North America. (Photo: SkyTruth; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, what's the technology that the satellite uses to the detect methane?

FRANKENBERG: It uses a technique called absorption spectroscopy. We are recording spectra for methane around 1.6 micron spectra range, which is not in the visible any more so the human eye can't see it. SCIAMACHY records about more than 8,000 spectra points, so if you imagine your eye is basically only seeing three different colors, the satellite is recording more than 8,000 different colors, and with that fine spectra resolution we can detect basically fingerprints of atmospheric trace gases in the atmosphere. And we use these absorptions of methane to derive the methane quantities that we have in the field of view of the satellite.

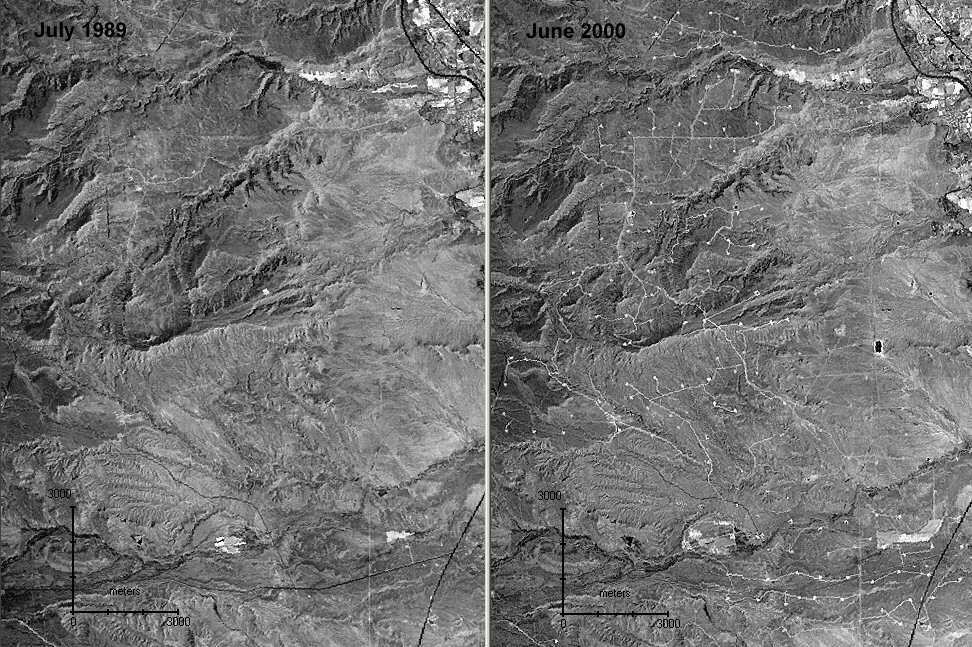

Coal bed methane production in the San Juan Basin occurs primarily in the Fruitland Formation, composed of interbedded sandstone, siltstone, shale, and coal. (Photo: SkyTruth; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: What do you suspect is the source of this methane hotspot that's observed there in the Four Corners area of the US?

FRANKENBERG: So in principle we can only observe the effect of emissions. We can't really with 100 percent certainty talk about the source itself, but this is a region where coalbed methane extraction is really big - it's one of the biggest extraction areas in the US - and this is the most likely source, I would say, right now.

CURWOOD: So your study looks at the satellite data from 2003 to 2009, but fracking, which people are very concerned about now for methane leaks has gone through a significant boom in the last few years. What does your data say since then?

FRANKENBERG: We only looked particularly at this Four Corners site, and we observed the enhancements already starting in 2003, and at the time there was no considerable fracking activity in this area. It's an established technique in the Four Corners area to extract the coalbed methane, and I think it started already in the 90s. Our main message is that we should not only focus on the new techniques like fracking, but keep the whole energy sector in view and not forget about those that already emit since a long time but they just get swept under the carpet now because all the focus is on fracking.

From 1989 to 2000, coal bed methane extraction in the Drunkards Wash field west of Price, UT increased significantly. (Photo: SkyTruth; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, the data that you observed, what percentage of methane emissions in the U.S. does this hotspot represent?

FRANKENBERG: In the paper we compared it against the US total estimate for natural gas emissions, which are around seven teragrams, and of this, the 0.59 teragrams that we observed would be almost ten percent of it.

CURWOOD: So, what's the value of locating this methane hotspot through remote sensing? How does it help us find and fix the source?

FRANKENBERG: I think one of the biggest advantages of satellite data like this is indeed in locating potential hotspots—problem areas where you might follow up with more dedicated ground-based studies to see the source afterwards. Each footprint of the SCIAMACHY satellite is about 60 by 30km so we can't really go any finer than the spatial resolution of the satellite, and this is what we are restricted with right now.

CURWOOD: Where else in the world are you seeing hotspots?

Christian Frankenberg studies remote sensing of atmospheric trace-gases at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. (Photo: NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory; CC government work)

FRANKENBERG: Oh, there are many, many others. The most prominent feature that we observe is typically the rice paddy season in Asia because it's a large emission occurring over a relatively short time period. It's focused on about two to three months of the year, and in this area there are about 30 teragrams of methane being emitted from rice patties. It's mostly the microbes that live anaerobically in the soil and then the rice plant itself is just a mediator of the emissions.

CURWOOD: So, Christian, in general, how does satellite data compare to ground monitoring? What are the advantages and disadvantages?

FRANKENBERG: The advantages are that you basically have a single instrument that measures around the globe, so all the inter-calibration issues are a little easier if you do it from space. You also have full global coverage. You might measure in regions where, be it for political reasons, be it for monetary reasons, be it for safety reasons, you can't really go there, so you cover those areas as well. On the other hand, since it is remote sensing, it will never be as accurate as in situ measurements, which are basically just measuring at the point where you do your ground-based measurements. These are very, very accurate and will always be needed, but they can't do that around the whole globe.

CURWOOD: Christian Frankenberg studies remote sensing of atmospheric gases at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. Thank you so much for your time.

FRANKENBERG: You’re welcome. Nice talking to you.

Related links:

- The study, published in Geophysical Research Letters

- Original NASA press release on the methane hotspot

- High Country News coverage of the hotspot

[MUSIC: Outkast from “My Favorite Things” from The Love Below (Arista 2003)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: politics and power plant emissions in Pennsylvania. That’s just ahead. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Outkast from “My Favorite Things” from The Love Below (Arista 2003)]

Cap and Trade Heats Up Pennsylvania Gubernatorial Race

Pennsylvania ranks fourth in the nation for coal production and third for carbon dioxide emissions. (Photo: Ed Whitaker; Flickr CC)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. For more than a decade, a group of northeastern states has conducted a cap and trade program for power plant emissions know as RGGI, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, that’s said to have saved billions of dollars and slashed millions of tons of CO2 emissions. Now, as power plant operators across America consider new rules expected from the EPA next year, states including Pennsylvania are thinking about joining RGGI. But that decision likely depends on the November election, with incumbent Republican Tom Corbett and Democratic contender Tom Wolf on opposing sides. Julie Grant of the public radio program the Allegheny Front has the story.

GRANT: Under President Obama’s clean power plan, Pennsylvania would have to cut its carbon dioxide emissions more than 30 percent by 2030. If Democratic candidate Tom Wolf is elected governor, he says he would join the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, also known as RGGI.

WOLF: I want to be part of any compact that’s trying to make our air cleaner, and I think RGGI tries to do that.

GRANT: RGGI is an agreement between nine Northeastern states to voluntarily reduce the amount of carbon dioxide coming from electricity generation, through a cap-and-trade type program. Adam Garber is with the advocacy group PennEnvironment. He says Pennsylvania could use RGGI as a way to meet the EPA mandates.

Dem. PA Governor candidate, Tom Wolf, campaigns in Pittsburgh. (Photo: J.S.Jordan/Allegheny Front)

GARBER: By joining an existing framework, it’s going to be easier for Pennsylvania to show that it’s meeting these standards.

[SOUND OF CLIMATE MARCH]

GRANT: Garber says Pennsylvanians are ready for this kind of action, as witnessed at the recent UN Climate Summit.

GARBER: I think after you see 400,000 people march in NYC, including thousands of Pennsylvanians, it’s very clear what people in the state want, which is a world not threatened by climate change, a world where we’re getting more energy from renewables like solar and wind. I think the political will and the people will is there, and it’s a question of the politics.

GRANT: RGGI was first proposed by a Republican, former New York governor George Pataki. New York, Vermont, Connecticut, and others voluntarily agreed to cap the emissions of carbon dioxide coming from the electricity sector. Any plant that generates 25 megawatts or more of electricity in RGGI states must purchase one allowance for each ton of carbon dioxide it emits. The allowances are sold in quarterly auctions. Proceeds go toward energy efficiency and clean energy programs, and to lower consumers’ energy bills in member states. But as the politics of climate change heated up, conservatives vilified cap and trade programs. In 2011, Republican New Jersey Governor and possible presidential contender Chris Christie pulled his state out of RGGI.

CHRISTIE: RGGI does nothing more than tax electricity. Tax our citizens, tax our businesses with no discernable or measurable impact upon our environment. So we will withdraw from RGGI in an orderly fashion by year’s end.

GRANT: Christie said New Jersey electricity generators were at a competitive disadvantage because Pennsylvania coal plants didn’t have to pay for RGGI’s carbon allowances. But in the three years since, environmentalists say exiting RGGI cost New Jersey $114 million dollars for clean energy projects. RGGI says proceeds in 2012, the latest available numbers, for all its members combined were expected to return more than $2 billion dollars to ratepayer bills, while offsetting 8 million tons of carbon dioxide.

Rep. PA Governor Tom Corbett, at a Labor Day rally for coal in Pittsburgh. (Photo: J.S.Jordan/Allegheny Front)

GRANT: But Governor Corbett’s Energy Executive Patrick Henderson says Pennsylvania is in a whole different ballgame. The state has many more coal-fired power plants, produces much more power, and emits more carbon dioxide than the current RGGI states.

CORBETT: Pennsylvania compared to those states is an absolute anomaly. Several of those states don’t even have a single coal-fired power plant at all.

GRANT: Pennsylvania, on the other hand, is one of the nation’s top energy producers and exporters of electricity to other states. That’s why the EPA’s plan to cut carbon emissions has Pennsylvania’s coal industry worried.

[CROWD AT COAL RALLY]

GRANT: Workers from coal plants and mines concerned about their jobs rallied in Pittsburgh last month to stop the so-called “War on Coal.” Henderson says the new federal regulations might force some coal plants to close. He says the RGGI standards are even tougher than the federal rules, and joining could overburden Pennsylvania’s coal plants. But Democrat Tom Wolf says Pennsylvania could negotiate a fair deal with RGGI.

WOLF: “It’s basically exercising leadership, yeah.”

GRANT: The proposed federal rules require each state to have a final plan in place in 2017. If they work with other states in a regional compact, like RGGI, they get an extra year to comply. I'm Julie Grant.

CURWOOD: Julie Grant reports for the public radio program the Allegheny Front. We invited Governor Corbett to explain his views on RGGI, but he declined.

Related links:

- Read more about the story on Allegheny Front’s site

- The EPA’s final rules for power plants

- President Obama’s Clean Power Plan Proposed Rule

- More on PA candidate for governor, Tom Wolf

- More on PA Governor Tom Corbett

- The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI)

- RGGI’s initial proposal

- RGGI states must purchase carbon dioxide allowances at quarterly auctions.

- Historically, conservatives have vilified cap and trade programs

- RGGI provides benefits to taxpayers and offsets carbon dioxide

- Pennsylvania is one of the nation’s top energy producers and exporters of electricity

Beyond the Headlines

River rafters in Colorado. A new report has placed the value of Colorado’s rivers at $9 billion dollars. (Photo: David Herholz; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: And now we turn to our guide to the world beyond the headlines – Peter Dykstra. He’s also the publisher of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org. He joins us now on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter, what stories did you find today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve, let’s start north of the border this week. Canada’s taken a lot of heat in recent years for the perception that it’s turned a deaf ear to environmental concerns, but their latest harsh critic is a little bit surprising.

CURWOOD: Yeah, the Canadian Government’s done an about face with climate change, what with pulling out of Kyoto. They’ve made deep cuts in scientific research and quite a bit more, but who’s their latest critic?

DYKSTRA: The Canadian Government’s latest critic would be the Canadian Government, Steve. There’s a scathing report from the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development – she doesn’t run the Environment Ministry, but serves as a watchdog – and she says that Canada’s well on its way to failing to meet its promises for fighting climate change, reducing emissions, protecting the melting Arctic, and for monitoring at its controversial tar sands projects.

CURWOOD: And earlier in the show, we reported that some corporations are pulling out of the tar sands, but an internal government spanking, too? This scathing report, does it have any teeth, or can the Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper just brush it off?

DYKSTRA: The Environment Ministry is required to respond to the scathing report. And the Commissioner who wrote said scathing report answers to Parliament, not the Prime Minister. The contents of the report might make for some debating points, but not necessarily big changes.

A Canadian protester objects to additional Canadian tar sands projects on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. (Photo: Peter Blanchard; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hmm. So, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: We have a tale of two economic analyses. Like most of the West, the snowpack and rainfall in Colorado has been a little funky for the past few years, and water’s a big deal for the state’s economy, including everyone from ranchers to rafters. Agriculture wants to take water out of the rivers; tourism wants to leave it in. And the state’s new water plan took the first step of putting an actual price tag on Colorado’s river economy, so at least they know how much money they’re fighting over, and that amount is $9 billion dollars.

CURWOOD: Hey, you’re talking literally about a lot of cash-flow.

DYKSTRA: Right, but not nearly as much as in the Chesapeake Bay. A report from the Chesapeake Bay Foundation estimates that the proposed massive cleanup plan for the Bay will cost about $5 to $6 billion dollars a year, but the cleanup could yield as much as $129 billion a year in benefits like storm protection, increased seafood production, tourism and cleaner water.

CURWOOD: That’s certainly a familiar environmental theme – if you spend money wisely, you get a big payback. Time now for us to check out the environmental calendar. What did you bring us from the history calendar this week?

DYKSTRA: Happy 75th birthday to the nylon stocking. In the early 20th century, the DuPont Company, one of the nation’s oldest makers of gunpowder, diversified into the chemical giant we know today and some of their biggest labs focused on developing synthetic fabrics. They called their big breakthrough, back in 1935, “Fabric 66” and immediately set out to deploy this secret weapon to replace silk stockings. At first they called it “Klis” – which is silk spelled backwards – then they hit upon the notion that these new stockings didn’t run as often as silk stockings, so they called the fabric “No-Run.” And that got corrupted into the word “Nylon,” and in October 1939, they rolled out their nylon stockings in every department store in DuPont’s Wilmington Delaware hometown, where eager ladies lined up around the block to buy them.

CURWOOD: Hey, Peter. You do remember that this is an environment show, and I appreciate your enthusiasm about nylon and DuPont getting a leg up, but where are we going with this?

Nylon stockings are now common in women’s clothing. (Photo: How can I recycle this; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, the world didn’t just go ape over nylon stockings, this was a high-water-mark in our embrace of manufacturing and chemistry toward a better way of life. When nylons showed up at the New York World’s Fair the next spring in 1940 and then they launched nationwide, they sold four million pairs of nylon stockings in four days, and it was on. DuPont called it “Better Living Through Chemistry.” Their rivals at Monsanto reminded us that, “Without Chemicals, Life Itself Would be Impossible.” And of course these things made life a lot better, or at least a lot easier - to grow more food, clean the house, kill mosquitoes and much, much more.

CURWOOD: But at a big environmental price.

DYKSTRA: Absolutely—a big price to rivers and air and soil, wildlife, and to our own bodies through pollution. But the notion of green chemistry is now beginning to be embraced even by companies like Dow and DuPont and Monsanto, using talents in the lab to do good without doing harm, and it brings hope that it will really bring better and cleaner living through chemistry.

CURWOOD: Hey, Peter, we’re out of time; so I guess I got to run.

DYKSTRA: Oh!

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is the publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN dot org and Daily Climate dot org. Thanks so much Peter, we’ll talk to you again soon!

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve; thanks a lot. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Canada’s report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development

- The Globe and Mail’s story on this report detailing Canada’s Environmental Shortfalls

- Colorado’s rivers are valued at $9 billion dollars

- Cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay provides large financial gains

- The history of nylons and DuPont’s green chemistry

- The Daily Climate

- Environmental Health News

Controversial Japanese Whaling

Minke Whale is the species most killed in Japanese Whaling practices. (Photo: Len2040; Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: At two hundred tons, the blue whale is the largest animal known to have inhabited the Earth, but it was hunted to near extinction back in the days of whaling. Thanks to a moratorium on whaling that began in the mid 80’s, the blues and other whales have been coming back, although very slowly. But the moratorium does allow whaling for the purposes of research, and in the name of science, the Japanese have killed thousands of whales in recent decades. Phillip Clapham directs whale research at NOAA’s National Marine Mammal Laboratory in Seattle. We called him to discuss Japan’s whaling research program.

A Humpback whale breaches. (Photo: Colin Baxter Photography)

CLAPHAM: Since the moratorium, Japan has killed a large number of whales. It claims that’s necessary research that's important for the management of whaling. Many of us believe it is simply a convenient way around the moratorium.

CURWOOD: So what exactly are the research whaling programs that Japan has? You said they've killed thousands of whales under this program.

CLAPHAM: Since 1987, they've killed more than 14,000 whales under this program, and the program actually exists in two places; in the Antarctic, and there's a parallel program in the north Pacific. There's really very little the Japanese are doing that is of direct relevance to the management of whales and even if it is, nowadays there are so many nonlethal techniques, which are as good or in many cases better than the technique of killing a whale to study it.

CURWOOD: What types of whales are being taken?

An adult and sub-adult Minke whale are dragged aboard the Nisshin Maru, a Japanese whaling vessel that is the world's only factory whaling ship. An explosive-packed harpoon reportedly caused the wound that is visible on the calf’s side.

Australian customs agents took this image in 2008, under a surveillance effort to collect evidence of indiscriminate harvesting, which is contrary to Japan's claim that they are collecting the whales for the purpose of scientific research. (Photo: Australian Customs and Border Protection Service; CC-BY-SA-3.0-au)

CLAPHAM: Primarily it's a small whale called the Minke whale, which is the smallest of the so-called large whales. There are also, in the north Pacific mostly, some other whales being taken: Sperm whales, Brutus whales, Sei whales, which are much bigger whales.

CURWOOD: Now as I understand it, the international Court of Justice recently made a finding about Japan's research whaling programs that would require Japan to stop that.

A Humpback whale and her calf. Humpback whales are one of the species taken from the Antarctic and killed for Japan’s scientific “research” under the JARPA II program. (Photo: Colin Baxter Photography)

CLAPHAM: Well, yes and no. The ICJ decision was very interesting. It happened in March this year. And Australia and actually New Zealand took Japan to the Court of Justice, and they claimed that the scientific whaling that Japan was doing was actually not for the purposes of scientific research. So what the court did was to look at a number of factors: the scale of the Japanese catch in the Antarctic, the way that they calculated the sample sizes, the number of animals they've actually killed relative to the sample size, what the timeframe and the publication record was, and how well they had coordinated with other research programs. And the courts, after looking at all this, came out and said that actually, no, it wasn't for the purposes of scientific research, and therefore Japan had violated that article, Article 8, of the Convention. So what the court then did was to say, “You [the Japanese] must basically cancel and revoke any permits for this particular program, which was in the Antarctic and not issue any more.” It didn't, however, affect the north Pacific program, and many people at the time were very optimist about this. They thought this would be a way for Japan to cancel its Antarctic whaling operation finally, and maybe it would actually extend to the north Pacific. But as we've seen in subsequent months, none of that has happened.

CURWOOD: So Japan is still in the Antarctic and in the north Pacific.

A minke whale breaches. (Photo: Martin Cathrae; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CLAPHAM: Yes, they continue the north Pacific program this summer, albeit with a somewhat smaller catch, and they've announced their intention to submit a new proposal to the Whaling Commission. And no matter what criticism they get of that proposal, they will say that it is in keeping with the ICJ judgment, and they'll go ahead and start whaling again starting in late 2015 back in the Antarctic.

CURWOOD: Why do the Japanese take so many whales and then use so little of it? I gather there's quite a bit in cold storage at this point.

CLAPHAM: Yeah it's a complicated question. So it's a question really at a couple of levels. So, the research in Japan is conducted by a sort of quasi-governmental organization called Institute of Cetacean Research in Tokyo, or ICR. And ICR is funded by government subsidies and also by the sale the meat in Japanese markets, so there is a very strong incentive to continue whaling because, essentially, if whaling stops, then that institution goes out of business. There's also the larger issue of: the Japanese regard whaling as, really, a slippery slope. If they give in on whaling, then perhaps they are going to have to give in other fisheries issues too, and fish, as you know, is a major part of Japanese culture. Japan is a huge consumer of seafood, and so I think they’re really concerned that if they give in on whaling then Bluefin tuna, or something else they depend upon, may be next.

The Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) is found in all oceans of the world and can weigh up to 70 tons and measure up to 88 feet. They may migrate to subtropical waters for mating and calving during the winter months and to the colder areas of the Arctic and Antarctic for feeding during the summer months; although recent evidence suggests that during winter fin whales may be dispersed in deep ocean waters. (Photo: Chris Buelow; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, in terms of fishing some Japanese folks say that, “Look, you need to limit the number of whales because they eat fish, and, of course, we want to have fish.” What does your research tell you?

CLAPHAM: It's really a ridiculous argument. First of all, many of the big whales don't eat fish at all. In fact, the largest biomass of the world's Baleine whales live in the southern hemisphere, and they consume primarily krill there. You know, you need to consider the size of many whale populations—today they are at a small fraction of what their levels were in pre-whaling times when commercial fish populations where considerably larger and much healthier than they are today. There's a lot of other issues in this as well. Human overfishing clearly is the cause of the precipitous decline of commercial fishstocks worldwide; it isn't really whales. And, in fact, there has been some recent studies that have suggested that, to put it bluntly, through defecation, whales contribute really invaluable nutrients in large quantities to the marine environment, and in doing so, stimulate primary production, which is that the base of the whole food chain.

A Humpback whale surfaces for a breath. As a species, their population numbers are recovering. (Photo: Colin Baxter Photography)

CURWOOD: Phil, before you go, bring us up-to-date on just how whales are doing around the planet.

Dr. Phillip Clapham is the Program Leader of NOAA’s National Marine Mammal Laboratory’s Cetacean Assessment and Ecology Program, in Seattle, Washington. (Photo: Courtesy of Phillip Clapham)

CLAPHAM: Well, it depends on which species you're talking about. Actually I'm happy to say that many whales are doing very well. In the 20th century when industrial whaling really kicked into gear, two million whales were killed in just the southern hemisphere alone, most of those in the Antarctic, and there were several hundred thousand killed in the northern hemisphere also. And we reduced populations of whales in some cases to well below 1 percent of what their original pre-whaling numbers were. There were 369,000 blue whales killed in the 20th century. Today they're probably a couple of thousand left in the Antarctic, so less than 1 percent of the original. There were actually almost three-quarters of a million Fin whales killed. But, fortunately, many of those species are coming back now; humpback whales, for example, they have come back remarkably well in most places. They're an estimated 20,000 in the north Pacific right now, probably around 10 to 15,000 in the north Atlantic, and they seem to be doing very well without human interference. They're very resilient.

CURWOOD: Phillip Clapham directs whale research for the National Marine Mammal Laboratory of NOAA in Seattle. Thank you so much, Sir.

CLAPHAM: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- International Court of Justice’s judgment regarding Japan’s JARPA II program

- Japan’s Institute of Cetacean Research’s (I.C.R.) website

- Phillip Clapham’s NOAA website

[MUSIC: LCD Soundsystem “You Wanted a Hit” from This Is Happening (DFA 2010)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: we stick with whales for a musical duet and play along with nightingales. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Miles Davis: “So What” from Kind Of Blue (Columbia 1959)]

Life For A Humpback Whale

.png)

A Humpback mother and her calf glide by off the New England coast. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Humpback whales are found in every ocean, and so is the roar of human activity. But there’s calm at the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary off Massachusetts, where writer Mark Seth Lender encountered a humpback and her calf.

The mother breaches. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

A Humpback Whale Seen Logging beside her Calf of the Year

Stellwagen Bank

© 2014 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: Wide of the planet Humpback Whale, goes, and dives, and rises up to feed rolling upon her fins, the fishes leaping amongst the black baleen in the cavern of her mouth. And when she roves, her flukes footprint the water like the heel of a giant ocean striding. And when she breaches, broad jumping high and long, the sea rumbles like kettle drums when she falls down! And when her water breaks and the life she bears is born, the tides rise higher on the distant shore.

The ragged sheets of rain weaving the spiny sea when the waves roar, the smooth cloth of the sea in calm, the ruffled blanket of the sea in steady wind, these are the weathers Whale knows, all these, and more.

The calf surfaces for a breath and dives again. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

In the grey of the deeps no color shines, sound rules over the eyes, the touch of currents is the only wind against your face, and water the only air; where cold inclines and warm subsides and water falls within water, there Humpback glides, and speaks, and listens for the voices of her kind through the unaccustomed, the invidious clamor.

She surfaces for silence and for sleep.

Effortlessly, the whales push the water past them with each stroke of their flukes. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Whale, and the baby born to her in the winter of the year doze and drift on a soft bower of water. Their eyelids droop and close. They are so still; cradled in the calm before the storm. And when they draw, and blow, their breath becomes Whale Bows, violet, crimson, sintered green. It vanishes as quickly as it blooms. And when they sound, fathoms and fathoms below, the water like fresh blue paint covers over the place where they have been. And when they race, like a miller’s wheel, head then back then tail, great currents are moved upon their way. And when they look they see you.

The Whale – Feels! The Whale – Breathes.

The young whale, born tethered to his mother by the hawser of the cord, like all of us bound to the fate of the sea...

A mother Humpback whale rolls under the waves in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

As the sea goes, so goes the Whale. As the Whale goes, so goes life, on earth.

CURWOOD: Writer Mark Seth Lender has pictures of the humpback and her calf at our website, LOE.org.

Mark Seth Lender has dedicated this essay to the memory of Stephen Kramer.

Related links:

- Provincetown's Dolphin Fleet

- Mark Seth Lender’s site

A Man, His Clarinet and Nature’s Singers

David Rothenberg is covered in cicadas as he plays along with their collective buzz. (Photo: Charles Lindsay/Courtesy David Rothenberg)

[MUSIC CLIP WITH CICADAS AND CLARINET]

CURWOOD: David Rothenberg is a philosopher and musician who likes to collaborate when he plays his clarinet, as here, in this track from his latest CD - Cicada Dream band - which features birds, bugs and whales. Now, biologists tell us that creatures sing or call or howl for a reason – to mark their territory, to warn of danger or to attract potential mates. But David Rothenberg, who is a professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, thinks that some animals sing simply for the joy of it, and that’s why he likes to play along with them. Professor Rothenberg joins us now from Cold Springs, New York. Welcome to Living on Earth.

ROTHENBERG: Thanks so much for inviting me.

CURWOOD: So growing up what was your personal interaction with nature and its sounds?

Rothenberg played with a Veery thrush and also manipulated the sound by slowing it down. (Photo: Christopher Elliot; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

ROTHENBERG: Well, I grew up in Connecticut, kind of in the suburban countryside, and I was always going outside behind my house into the meadow and by the river and listening to sounds. I was always interested in music and also natural world, and trying to figure out how to connect them.

CURWOOD: So, David, everyone hears the sounds of nature walking through the woods, but not everyone hears music like you do. One example is a little experiment you did with a Veery Thrush song. Let's play the thrush song as you would hear it in the forest.

[VEERY THRUSH SONG AT NORMAL SPEED]

CURWOOD: And then you took that song and slowed it way down.

[VEERY THRUSH SONG AT SLOW SPEED]

CURWOOD: Wow! Who would've known? What did you take away from this little experiment?

ROTHENBERG: I mean, this is one of the most surprising examples of taking a birdsong in its real speed and slowing it down, kind of into the human realm of hearing. And you hear what's already in there, and you hear what the birds are getting. And you kind of grasp how this song can mean so much to the female Veerys that hear it. You know, birds hear five times faster than we do. The Veery on its own is going [WHORLY SOUNDS], and this is kind of a somewhat familiar but strange sound you hear in the woods. To bring it into the human realm, bring the pitch down, this song is an amazing example of the music contained in that little phrase, it really sounds like a jazz trumpet phrase.

David Rothenberg plays his clarinet with a Starling. (Photo: Courtesy Cheetah Television Ltd)

[VEERY THRUSH SONG AT SLOWED DOWN]

ROTHENBERG: [SINGS JAZZ TUNE SIMILAR TO SLOWED VEERY SONG] It's got all the qualities of a good jazz phrase. It's got not only a form and structure, but a real quality of performance and emotion and verve to it somehow; like, if you were playing that it in a lesson with your teacher, they'd say, "Yeah, you got it. You’ve got it figured out."

CURWOOD: Uh-huh. You know, I always thought John Coltrane got his rifts from the Wood Thrush.

ROTHENBERG: Ah! What did he say to that? He probably did.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Now you have a new record out; it's called the "Cicada Dream Band." And there are sounds from cicadas, crickets, whales, but you also have some other musicians on this.

[MUSIC CLIP FROM RECORD]

CURWOOD: How does playing with creatures change when you're joined by other human musicians?

Cicada Dream Band’s album cover. (Photo: Charles Lindsay)

ROTHENBERG: Well, this album came out of the concerts we did when the cicadas were emerging last year, 2013, in the New York metropolitan area, and every 17 years this happens. I had heard that 17 years before, that Pauline Oliveros, the famous experimental composer had done a whole festival of cicadas; so I said, "Let's do it again." So we performed in New York City and in some other places, and in the record we ended up with Pauline playing this kind of digital accordion called a V-accordion along with Timothy Hill, who’s an overtone singer. He specializes in singing—you can sing more than one note at the same time, kind like birds and insects can do. And so we formed this group, and so we kind of based the music, you know, not so didactically like some of my other records have done, but really kind of use it as part of the mix. So we are playing live. I was playing clarinets and also computer, playing some of these sounds, and we were kind of improvising together to form music around the whole possibility that all these sounds are out there in the natural world. And what I hope in this whole process is that my own music and the music of my collaborators—human and from other species—has changed by the encounter, like it leads to something new that we couldn't do on own.

CURWOOD: You've played with different kinds of creatures: birds, whales, cicadas even. So talk about the similarities and differences of playing with those different animals.

ROTHENBERG: Well, the thing is with playing with insects then you are one sound in the midst of millions. It's very humbling to make a little noise in around you. You hear so many individuals altogether forming this kind of collective musical composition where everyone's doing their own little part and somehow it fits together. And although at first it might sound like noise; when you pay closer attention to it you realize there's a lot of organization going on there. With birds you get a sense you're connecting to an individual: an individual is doing something and you're responding to it. And of course it's one thing to take the song, slow it down, make it sound that you interact with, like in the studio or in a concert where you’re playing the recording. That's kind of easy in a way. What's more challenging and kind of daring and surprising is to do it in the wild where you don't know what's going to happen. Like last year I was out in Berlin in late spring playing with nightingales in these parks. Berlin is somehow full of nightingales and they just sing very intensely in the middle of the night.

Rothenberg plays music with many creatures including the Nightingale. (Noel Reynolds; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So how did the nightingales respond to your clarinet?

ROTHENBERG: They kind of keep jamming with you. Scientists have told us there's three ways the nightingale will respond to a sound played to it.

[NIGHTINGALE SINGING]

ROTHENBERG: They will alternate. They will let you do your sound; then they'll do something.

[NIGHTINGALE SINGING AND ALTERNATING CLARINET]

ROTHENBERG: Or they can try and compete with you and jam what you're doing. When alternating, it's a more peaceful sense of, OK, you've got your space; I've got mine. When they're kind of interrupting you constantly it's more like a competitive situation: they're trying to define their territories against yours.

[NIGHTINGALE SINGING AND COMPETING WITH CLARINET]

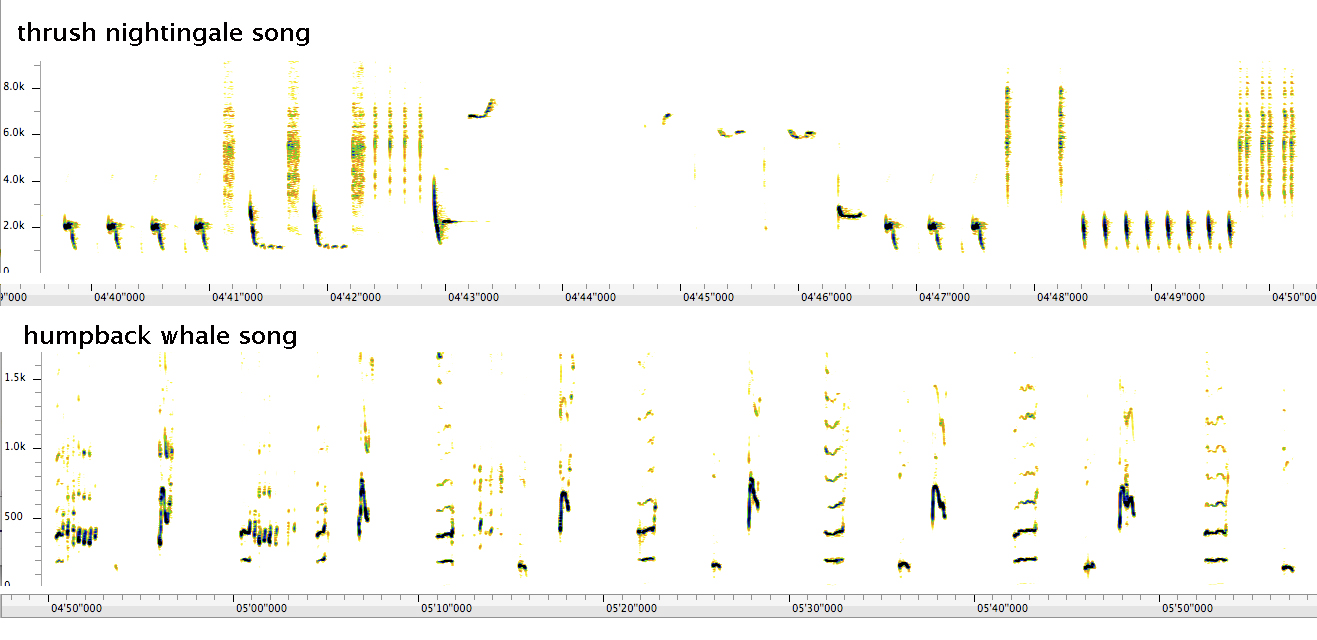

Comparison of the frequency and duration of a nightingale’s song to that of a humpback whale. (Photo: David Rothenberg)

ROTHENBERG: And then finally, the most superior, top nightingales just ignore what you do—maybe they sing, maybe they don't. They couldn't care less.

[NIGHTINGALE SINGING AND IGNORING CLARINET SONG]

ROTHENBERG: This is similar to, say, human jazz musicians—these three types of musicians you will easily meet onstage. Any jazz musician would confirm that.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Well, maybe the jammers are trying to teach you how to play the clarinet a little better.

ROTHENBERG: I'd say sometimes. You know, there's a recent scientific study written by these scientists in Berlin saying that, you know, the nightingales are either playing rhythmic clicks or whistle songs [CLICKING AND WHISTLING], but occasionally they make this sound, which the scientists describe as an "ugly" sound like [MEAH MEAH]. But I listened to it, and all the other musicians we had out there playing with nightingales—it just sounded like a cool bent blue note like a [MEAH MEAH]. And whenever it did it, everyone would smile and laugh because it sounded so cool. It was interesting: the scientists just thought it was unmusical, and all the musicians said it was very musical.

David Rothenberg, headphones on, listens to the sounds of humpback whales and plays along into a microphone. His sound is then transmitted to the whales through an underwater speaker. (Photo: Dan Sythe/Courtesy David Rothenberg)

CURWOOD: So birds like half notes, huh?

ROTHENBERG: They like blue notes like in between the major and minor, like we all do, these in between things that you can't quite define, just like the Veery song has this swinging bluesy quality: ba-da ba-da ba-da. That is surprising ending, but it's just the perfect ending. And every animal that sings is really a world in itself. They all have their own aesthetic sense, something Charles Darwin talked about. Like he wrote in "Descent of Man", birds have a natural aesthetic sense. They appreciate beauty; that's why they've evolved beautiful feathers and beautiful songs. People often forget that. It's not a very common subject to study biology—the aesthetics of evolution—but I'm happy to say more and more scientists are starting to take this more seriously.

CURWOOD: A long time ago, Beatrice Harrison went out with her cello to play with nightingales. What did you think of her music?

ROTHENBERG: Well, what’s so fascinating about that story is this is the first outdoor radio broadcast ever made; so it was a really big deal for the BBC to do this in the 1920s. And they repeated it every year up until World War II; it was a very famous and popular program. And she was confirming just what I was saying: that you can play any sound, the nightingales will join in.

CURWOOD: Let's listen to a little bit of Beatrice Harrison.

[BEATRICE HARRISON CELLO PLAYING DVORAK’S “SONGS MY MOTHER TAUGHT ME” WITH NIGHTINGALE OBBLIGATO]

ROTHENBERG: To listen to this, you really have to put yourself back in mood of the 1920s, when a sound just like that, just as scratchy, was heard as being incredibly realistic, incredibly unique, something utterly new, like a sound recording outdoors mixing humanity and nature. No one had heard anything like that before hearing this. So you just have to say, wow, listen to this; humans can reach across to nature playing a human instrument that birds respond [to] and more than that, this broadcast on shortwave was heard all over the world.

CURWOOD: David, what do you learn about nature, or at least the creature you play with when you do this?

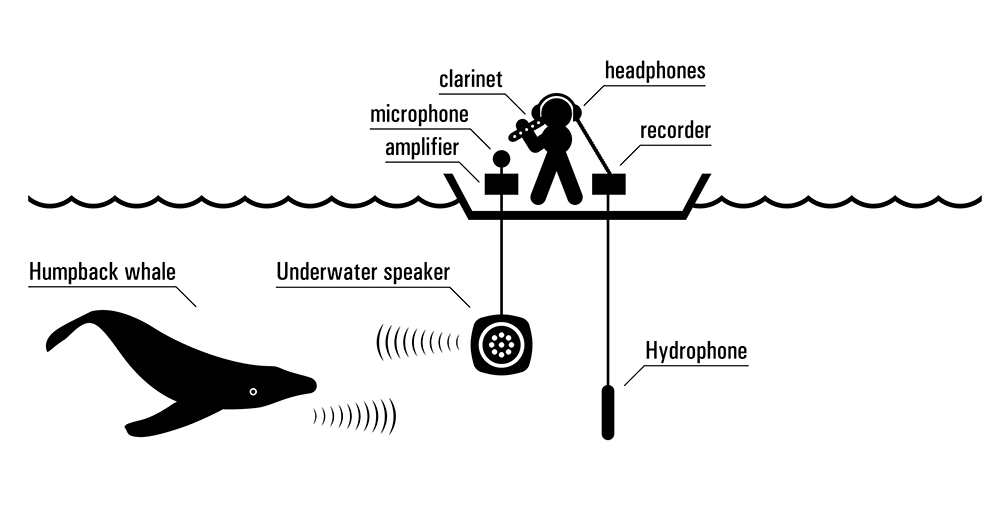

Diagram of David Rothenberg’s setup when he plays with whales underwater. (Photo: David Rothenberg and Martin Pedanik)

ROTHENBERG: You learn that there is music in nature; it's not just a human imposition. It's this aspect of evolution that Charles Darwin was well aware of, but today it's hard to find a biology textbook that admits that evolution creates a lot of weird, cool, beautiful stuff. I wrote a book called "Survival of the Beautiful" just dealing with this aspect of evolution: that evolution produces all this beauty, which is amazing, but you can't always explain it away with some practical purpose. And I think this has profound implications for how we understand nature. The way so many animals communicate is in a way much more like music than like language. They repeat the same phrases over and over and over again, so they're not just saying some specific message like, "Hey, I'm here. I'm hungry. Look at me." They need to say this with the phrases that are shaped and formed, and you find that in all kinds of animal sounds, even in these long songs of humpback whales, the complete song of which takes about 20 minutes to sing. Already in the 1970s, Katie Paine was writing that these songs have a structure, and you could say they have a sense of rhyme at the end of a long phrase. They come to the same sound. And they'll sing something different, and it'll come to the same ending – a sound like [SCREECH] at the end of a long phrase.

CURWOOD: OK, you listen to the animals, and you play along. So to what extent do they listen?

ROTHENBERG: Well, that's a good question. We can study the hearing apparatus of different animals so we know what kinds of frequencies they hear, but it's harder to know what's going on in their minds. Birds have been the most studied in this regard. You can tell what goes on inside the brain of a songbird. Certain areas light up when certain sounds are played or sung. They do respond to certain kinds of things. What's so fascinating with insects is that many of them make sounds they can't even hear. Why does that happen?

CURWOOD: And the answer is?

ROTHENBERG: We don't know. Much of this is just not known. The notion that animals are making music has been understood by humans for thousands of years. Musicians have thought about it. Scientists have thought about it, but they debate whether it's a useful way to think about nature in a scientific way. Is it just a human subjective imposition or is it a useful way to analyze that?

CURWOOD: Let’s listen to another clip now. This is from your record Whale Music. The tune is called "Never Satisfied".

Humpback whale glides by. (Photo: Courtesy Tomawak Productions)

[WHALE SOUNDS WITH CLARINET]

CURWOOD: What was it like playing with the whales? Where were you? When was it? How long did it go on?

ROTHENBERG: It's not so easy to play clarinet along with humpback whales. One reason is that they're underwater and I was sitting on a boat wearing headphones. You can't tell where the sound is underwater; there's no sense of space. It's just everywhere around. It's ether louder, nearer or quieter, further. So this whale was right under the boat. You could almost hear him without the headphones at all. And what's interesting about humpback whales is they’re always changing their song, always listening for new sounds, and it makes it interesting to play with them because sometimes, only sometimes, they respond to what I'm doing. I have to say I have done this for many hours, and most of the whales seem to ignore me, no surprise. But in this one example I showed you, you can really hear that as the clarinet plays a steady note [MIMICKS CLARINET NOTE], then the whale actually tries to go [WHALE MIMICKS NOTE]. He tries to sing in a more steady way than he usually does.

A Humpback whale breaches. (Photo: Courtesy Tomawak Productions)

[WHALE SONG WITH CLARINET]

ROTHENBERG: Whales don't usually sing horizontal steady sounds. They're usually more going [UP NOTE] or [DOWN NOTE], they go up and down like that. And so this is a kind of surprising moment where the whale showed some interest. And so, at that moment, you feel like, ah, maybe something's going on here—maybe there's a sense of getting through to another species through music.

[WHALE SONG WITH CLARINET]

CURWOOD: David Rothenberg is a musician, author and professor of Music and Philosophy at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. Thanks so much, Professor, for taking this time.

ROTHENBERG: Thanks a lot.

[WHALE SONG WITH CLARINET AND CICADAS WITH CLARINET]

Related links:

- David Rothenberg’s website

- Get the Cicada Dream Band

- David Rothenberg’s story in the New York Times about playing with whales

- Transcript of Living on Earth’s conversation with Paul Winter, a pioneer of playing music with animals

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of our team. Our show was engineered by James Curwood. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us please on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth