October 24, 2014

Air Date: October 24, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Cancer Risks from Mountain Top Removal Coal Mining

View the page for this story

Coal miners in Appalachia commonly practice mountaintop removal, blasting off hilltops to reach coal, and sending dust into the air that pollutes nearby communities. Host Steve Curwood spoke with Dr. Michael Hendryx, a Professor of Applied Science at Indiana University, about his group’s study that links the dust to increased lung cancer risks. (06:40)

Lead In Licorice

/ Rafael JohnsView the page for this story

Most worries about kids and candy concern tooth decay, but research shown some black licorice is contaminated with the neurotoxin, lead. Youth Radio’s Rafael Johns reports on the lead’s origin and efforts to make consumers sweet on licorice again. (04:25)

Carbon Capture and Recycling

View the page for this story

Companies are finding ways to turn industry-generated waste CO2 into a profitable business. Acting Assistant Secretary of Energy Christopher Smith tells host Steve Curwood why the DOE is investing in such ventures, including Skyonic’s, which October 21 started recycling CO2 from a San Antonio, Texas cement plant into chemicals such as baking soda and bleach that can be sold at a profit. (05:55)

It’s Tough To Turn Frack Water into Profits

/ Reid FrazierView the page for this story

Oil and gas fracking produces huge volumes of dirty, difficult to handle wastewater. Now businesses are developing technologies to clean it up. But Reid Frazier of the Allegheny Front reports profits can be elusive. (07:30)

Recycling E-Waste

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Discarded electronics are one of the fastest growing waste streams in the world, and a new survey from Best Buy found that only about 40% of people in the United State recycle old computers, TVs and phones, even though Best Buy and Staples are among companies that will take it for free. Most of the e-waste ends up in landfills, but as John Shegerian, CEO of Electronic Recyclers International tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer, it can be recycled safely and responsibly. (06:00)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood discuss the passing of a famous environmental whistleblower and remember a deadly smog attack in Donora, Pennsylvania. (05:10)

All-There-Is in Ten Hundred Words

View the page for this story

Roberto Trotta, an astrophysicist at Imperial College, London has written a new book, The Edge of the Sky, that describes the cosmos in the one thousand most common words in the English language. He tells host Steve Curwood about the challenges of describing All You Need to Know About the All-There-Is, and how non-scientific words can make science accessible to all. (12:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Michael Hendryx, Christopher Smith, John Shegerian, Roberto Trotta

REPORTERS: Reid Frazier, Rafael Johns, Peter Dykstra, Helen Palmer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. University scientists working in West Virginia report that mountaintop removal coal mining is not only bad for the environment, but also carries the risk of cancer for area residents.

HENDRYX: We found that dust that we collected from residential communities close to mountaintop removal mining sites caused changes in human lung cells that are indicative of cancer development and progression.

CURWOOD: Also, the universe explained using only the thousand most common words.

TROTTA: Science, of course, is sometimes a very intellectual activity but equally it’s important to remember that it's a human activity and as such is full of passion and creativity, and the aim of the book is to bring some of that back into the story and to speak to people’s hearts, not to their minds, only.

CURWOOD: The cosmos and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

Cancer Risks from Mountain Top Removal Coal Mining

Overburden dust from mountaintop removal coal mining is expelled into the air and carried on the wind for miles. Nearby communities exposed to this dust experience more health problems than those not exposed. (Photo: Bo Webb)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Mountain top removal is a controversial and highly mechanized method of reaching coal seams in Appalachia. Miners blast the top layers of rock and earth off ridge lines and dump the debris – called overburden – into valleys below. Now researchers have discovered this mining method is not merely destructive to the environment, but also creates dust that can promote lung cancer. Their study is published in the Environmental Science and Technology Journal and Dr. Michael Hendryx, of Indiana University, Bloomington, is one of the authors. He joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

HENDRYX: Thank you. Good to be here.

CURWOOD: So in your study, what did you find?

HENDRYX: We found that dust that we collected from residential communities close to mountaintop removal mining sites caused changes in human lung cells that are indicative of cancer development and progression. When we also exposed cells to dust from controlled communities farther away from mining we did not find those changes.

CURWOOD: And you're saying the most dangerous part, at least in terms of getting cancerous changes in lungs, has to do more with the rock that the coal is embedded in than the coal itself?

HENDRYX: That's true. It seems to be mostly what's called the overburden, the rock and soil above the coal, that's released during the excavation. It's released through the use of explosives and the use of large excavation equipment that raises dust levels in the nearby communities that can cause these types of health problems.

Components of overburden dust can cause irreversible lung damage and cancer when inhaled. (Photo: Bo Webb)

CURWOOD: And what are the ingredients from that overburden that gets into the dust that you think is related to cancer?

HENDRYX: It seems to be a complex mixture. We found elevated levels of silica on a pretty consistent basis. We've also seen elevations in levels of molybdenum and aluminum and also some compounds that are indicative of perhaps particles from the coal itself.

CURWOOD: So just how are such particles related to cancer in people?

HENDRYX: The particles, when they're inhaled, can cause a variety of changes to the body's response to try to, to deal with that foreign agent. Some of those are not specific to the chemical itself, but others, types of chemicals or elements such as silica and molybdenum can be particularly tumor promoting, so the mechanisms by which that happens are not totally understood, but it involves a variety of changes to cells in response to these foreign agents.

CURWOOD: How close are the households at increased risk of cancer to mountaintop removal?

Appalachian residents, retired coal miners and supporters march and rally at the White House, opposing mountaintop removal. (Photo: Rich Clement/ Rainforest Action Network; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

HENDRYX: In this study, we collected the dust samples within a mile of an active mountaintop removal mining site. In other studies that we've done we found evidence for elevations in particulate matter in the air within two or three miles. We don't know exactly what the progression would be as you move away from the mining, but I suspect that most of the effects are probably within five to 10 miles of active mining.

CURWOOD: Now, how important are your results, Professor? There's been concern that mountaintop removal might be related to cancer, might be associated with it, but what does this study do?

HENDRYX: This study is an important new development in my view because the previous studies by and large were epidemiological types of studies that looked at correlations between where people lived and their health status. So we've been able to document a number of occasions that there's higher cancer incidence and mortality including lung cancer for people that live near these sites. But until this study, we didn't have direct evidence linking the environmental conditions in these communities to actual biological changes in human lung cells. So this is an important new development in the research line.

Dust filters. The top left is an unused filter and top right is a control—particles collected from a non-mining area. The bottom four filters collected dust from various mountaintop removal (MTR) mining areas. Dust from these MTR mining areas contains silica, molybdenum, aluminum and other minerals that, when inhaled, cause irreversible cancerous changes to lungs. (Photo: Dr. Michael Hendryx)

CURWOOD: So how many people are afflicted by lung cancer in these regions close to mountaintop removal, compared to people living further away?

HENDRYX: We have done studies that estimate the people that live in the mountaintop mining regions might experience an additional 60,000 or so cases of cancer - that's total cancer not just lung cancer - but the extent of the lung cancer would be a sizable percentage of that.

CURWOOD: And, of course, people are going to say a lot of people in Appalachia smoke. How did you handle that?

HENDRYX: In the epidemiological studies that we've done we've shown that the lung cancer risks are greater even when we control for the effects of smoking. So it's not just a smoking effect, and in this most recent study, we exposed human lung cells to this dust, and it was only the dust collected from the mining communities that caused the cancer changes in the cells.

CURWOOD: Dr. Hendryx, who's most at risk in these communities of developing lung cancer?

HENDRYX: People who are at greater risk of developing lung cancer specifically are probably relatively older, and the risk of it is concentrated if you engage in other risks. So smoking, for example, it's probably a greater risk than exposure to the dust itself. People who maybe have other types of health conditions may be more vulnerable to pollution exposures as well.

CURWOOD: What kind of risks do very young people, babies, infants, young children, run from this?

Dr. Michael Hendryx is a Professor of Applied Health Sciences with Indiana University Bloomington’s School of Public Health. (Photo: Indiana University)

HENDRYX: We've done a couple of studies that have looked at health risks for children or for infants. We've found most disturbingly that the rates of birth defects are higher for mothers who lived in mountaintop mining areas during the time that they were pregnant compared to mothers who did not, again, controlling for other risks. We've also found that children that live in the mining communities are more likely to perform poorly in school which is an indication of poor cognitive development. So it's possible that children who are exposed to these environmental conditions are also suffering.

CURWOOD: So what do your findings mean now for the future of mountaintop removal, this part of the coal industry, in terms of health safety?

HENDRYX: In my opinion, we have enough evidence from this study and from others on both the public health impacts and the environmental impacts that this form of mining should be discontinued. It's environmentally irresponsible and it's a danger to public health.

CURWOOD: Michael Hendryx is a professor of Applied Health Science at Indiana University. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

HENDRYX: Thank you. Good to be here.

Related links:

- Read the study in Environmental Science and Technology linking Mountaintop coal mining to increased risk of lung cancer.

- Living on Earth spoke with Dr. Hendryx in 2012 about measuring mining’s toll on health

- Our story on Living Next to Coal—how residents of coal mining towns are more prone to lung, heart and kidney disease.

- Listen to our story on how coal dust might threaten wetlands

- Dr. Michael Hendryx is a Professor of Applied Health Science at Indiana University Bloomington

- New York Times article on OSHA’s rules for Silica Dust Exposure

- Silicosis and lowering your exposure to silica particles in dust

Lead In Licorice

The Center for Environmental Health sued candy makers and retailers for unacceptable levels of lead contamination in black licorice. (Photo: Rafael Johns)

CURWOOD: Well, it’s almost Halloween, and the kids will be out trick or treating for candy. And while you might worry about their teeth, there’s another more potent risk. Traces of the powerful neurotoxin lead can be found in some candy. This isn’t a new problem. Ten years ago we reported on lead in chili-flavored sweets imported from Mexico. That problem was solved, but the California Department of Public Health has found lead in some candies made in the US. Youth Radio’s Rafael Johns has the story.

[JELLY BELLY FACTORY TOUR]

[MUSIC: “Pure Imagination” from Willy Wonka]

JOHNS: The Jelly Belly Headquarters in Vacaville, California is kinda like Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory. There’s candy everywhere.

TOUR GUIDE: Good Afternoon everyone, on behalf of Herm Roller, our chairman of the Bean, I’d like to welcome you to the Jelly Belly candy company.

JOHNS: The place smells like a mixture of citrus, strawberries, and pure sugar.

TOUR GUIDE: Our top three flavors are very cherry, butter popcorn and black licorice.

JOHNS: So, very cherry, butter popcorn and black licorice. But black licorice in particular may not be as sweet as it sounds. Earlier this year, Jelly Belly, and other candy manufacturers like Trader Joe’s and Panda got a notice of violation. The non-profit Center for Environmental Health found these companies’ black licorice tested positive for lead. Jelly Belly declined to comment. The Center for Environmental Health isn’t releasing its test results.

Black licorice twists. (Photo: Melissa Venable; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

COX: Nobody should have to be a toxicologist just to buy candy right?

JOHNS: But Caroline Cox is. She’s also the Research Director at the Center for Environmental Health.

COX: Lead is what I like to call a stunningly toxic metal.

JOHNS: A metal that can affect the developing brain. Obviously how much of an effect depends on how contaminated the candy is, and what other sources of lead kids are exposed to. Cox says cumulative exposure to lead can cause problems in school.

COX: They’re going to get lower grades, they’re going to have more behavior problems. And that damage to the brain is essentially permanent.

JOHNS: The Food and Drug Administration recommends a maximum of 0.1 parts per million lead in candy. That sounds tiny. But even a tiny amount could make you sick. If lead is our problem as consumers, it’s also a big problem for the candy industry. Laura Shumow is the director of Scientific and Regulatory affairs at the National Confectioners Association, the Candy Lobby, with its 600 member companies.

Molasses is one of the main ingredients in traditional black licorice and is occasionally tainted with lead. Sometimes this lead is the result of pollutants in the soil or agricultural products like pesticide, which can contaminate the sugar cane. (Photo: Rafael Johns)

SHUMOW: It absolutely is something that companies are aware of, and it has allowed our member companies to investigate their own processes and their own supply chain, and understand the sourcing of these ingredients and how the risk of lead, they have as low of levels as possible.

JOHNS: Ten years ago one of the ingredients that came under fire was lead-tainted chili powder on spicy Mexican sweets. Now the culprit is the lead in molasses, which is one of the main ingredients in traditional black licorice. Sometimes this lead is the result of pollutants in the soil or agricultural products like pesticide, which can contaminate the sugar cane grown around the world, that is then used to make molasses. And once that lead gets in, it’s hard to get out. Again, here’s the Candy Lobby’s Laura Shumow.

SHUMOW: There aren't very many mitigation techniques to take lead out of an ingredient once it has been exposed, so in order to ensure that the food supply has very safe levels, what manufacturers need to do is to monitor their ingredients and to test the ingredients and that those levels are meeting regulatory standards.

Rafael Johns is a reporter with Youth Radio in California. (Photo: Ike Sriskandarajah/ Youth Radio)

JOHNS: The government currently doesn’t require companies to test all their ingredients before putting them into candy. The Center for Environmental Health finalized a settlement at the end of October, but many of the retailers and candy makers named in the suit have already agreed to pay fines and bring down lead levels in all the licorice candies they sell to below .035 parts per million by December.

[MUSIC: “Pure Imagination”]

JOHNS: One small step towards a…[SINGING] world of less contamination [to the tune of Pure Imagination from Willy Wonka].

For Living on Earth, I’m Rafael Johns.

CURWOOD: Rafael reports for Youth Radio. This story was edited by Ike Sriskandarajah.

[MUSIC: “Pure Imagination”]

Related links:

- In 2012, the candy company, Red Vines, recalled their black licorice for lead contamination.

- This year the California Department of Public Health found candies that tested positive for lead.

- Earlier this year, Jelly Belly, and other candy manufacturers like Trader Joe’s and Panda got a notice of violation for lead in licorice candies.

- The Center for Environmental Health

- The Center for Environmental Health expects sued retailers and candy makers for lead in candy. They expect a settlement by the end of the month—candy makers will pay fines and bring down lead contamination to acceptable levels by December.

- Our story on lead-contamination in Mexican chili-flavored candy

- Rafael Johns reports with Youth Radio in California

CURWOOD: Coming up: there’s a new game in town, carbon capture and recycle. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC:

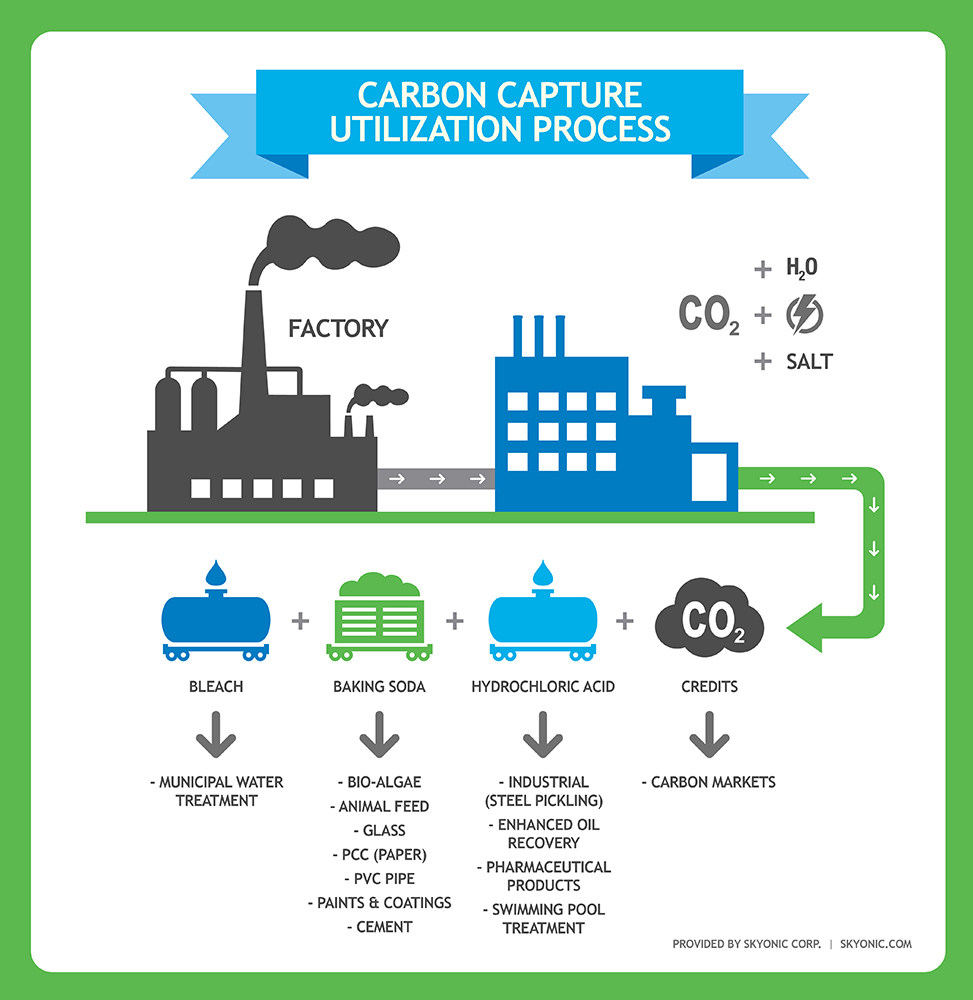

Carbon Capture and Recycling

A cement plant, like this one in Cupertino, CA, might one day contribute carbon dioxide to companies like Skyonic for profitable recycling. (Photo: Jitze Couperus; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. A Texas company has launched one of the first commercial operations to capture CO2 and recycle it into commodities, including baking soda. The Skyonic Corporation flipped the switch at a cement plant in San Antonio on October 21, and in a year expects to capture some 75,000 tons of global warming CO2, and turn it into industrial liquids and solids to sell at a profit. Skyonic says its process can also be used to recycle carbon from power plants. The US Department of Energy invested $28 million in the venture, and its acting assistant secretary, Christopher Smith, told me why.

SMITH: Over the last few years, we’ve committed over $6 billion to put in place real world projects that are taking CO2 that otherwise would be going into the atmosphere and capturing it and putting it to beneficial use, so that helps offset the cost of capturing the CO2 in the first place. So we see that as sort of a win-win.

CURWOOD: What is unique about what Skyonic is doing?

SMITH: Well, Skyonic is a plant that's using direct mineralization of emitted flue gases which is different from many of the other projects that we have separating CO2, compressing it, and then using it for other sources. So instead of having CO2 in a gaseous or in a compressed liquid form, you can actually turn it into a mineralized form that can be used in sodium bicarbonate or other usual products that didn't have some some salable value.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, Skyonic's process turns out sodium bicarbonate, baking soda, I guess, I used to brush my teeth with it sometimes; then sodium carbonate itself, hydrochloric acid, and then, what, it can make sodium hypochlorite, otherwise known as bleach?

Graphic of Skyonic’s carbon capture and utilization process. (Photo: Courtesy of Skyonic)

SMITH: Yeah, and bleach. So those are all...those are the four main products that would come out of this plant.

CURWOOD: How much sodium bicarbonate will this plant produce, and how does that compare to the demand for sodium bicarbonate here in United States?

SMITH: Well, in the grand scheme of things, sodium bicarbonate is not going to be a large enough market to alleviate the issues throughout all the CO2 we have to capture, but this is an important first step—to commercialize some processes, to take some things that we know in the laboratory, deploy them out in the field and have the result of actually reducing the amount of CO2 that's going up into the environment.

CURWOOD: So as I understand it, you could also use all this bicarbonate to make limestone, which of course is an ingredient in cement.

SMITH: Indeed. It can be used for limestone, it could be used for road material. So one of the things that's really interesting about these processes is that as you find ways to create new sources of material like sodium carbonate, and you do have new sources of sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate, you will subsequently find new uses for it.

Skyonic Projects Director, Norm Christensen, leads a tour of Board Members and VIP guests at Capitol SkyMine's Grand Opening on October 21st. (Photo: Courtesy of Skyonic)

CURWOOD: Now that Skyonic has its first commercial facility up and running, what do you think that means for other businesses who are trying to make money by capturing and recycling carbon?

SMITH: Well, that's a really important question, and that's I think an opportunity to talk of one of our other really important projects we have that’s called Petronova. It's a coal-fired power plant just south of Houston. In this case it's simply a retrofit of the existing coal-fired power plant. They're compressing the CO2, they're putting into a pipeline and they’re transporting it to a depleted oil field and using that CO2 to produce additional barrels of oil.

CURWOOD: But, Chris, it sounds a bit ironic, if you capture CO2 to get more fossil fuel. Doesn't that keep adding to the climate problem?

SMITH: Well, I mean, here's the way you should think about that. If you have more oil that's available domestically, that doesn't mean that the economy is going to be using more oil. What that means is you're going to be importing fewer barrels of oil from other countries. You're doing a lot of really useful things. You're importing less oil, which means you're not bringing it from distant sources. You're creating opportunities right here in United States including jobs and economic development. You're increasing our balance of trade. The CO2 is being sequestered. You're producing a barrel of oil that never would've been produced otherwise, but you're not increasing demand.

CURWOOD: Now, how do you think that President Obama's proposed power plant rules affect this kind of business?

SMITH: Well this is going to be creating a new market for these type of projects. It's going to be a new incentive for companies to innovate, to move forward to reduce the cost of capture, and indeed, in the case of a project like Skyonic that we're talking about today, find new beneficial uses for that CO2.

Christopher Smith is the Acting Assistant Secretary for the Department of Energy’s fossil energy program. (Photo: Courtesy of the Department of Energy)

CURWOOD: Supporting projects like this...what's the risk that the funds are getting diverted from alternative energy?

SMITH: Well, there's still a tremendous interest in all of the research and development that we're doing with the Department of Energy: wind, solar, enhanced geothermal, nuclear, but we also have to think about the energy sources of today because not only here domestically in the United States, but also around the world there's a lot of coal that's being burned, a lot of coal that's being used, and we have to deal with that, so we have to come up with smart solutions and you have to invest in a lot of different areas because science being what it is, you don't know where it's going to take you. Every time that we have a success like this, every time we're able to take something from the lab-scale and deploy it out the field, it's important because were taking an idea and turning it into a reality.

CURWOOD: One more question before you go...right now in the American economy there's not really a price for carbon, at least on a national basis. To what extent are businesses like Skyonic going to be viable without a price for carbon?

SMITH: Well, I mean that's actually a really good question. Over time, we're going to need a price on carbon in order to capture CO2 at the scale that one would need in order to confront the challenges of climate change, but for now it's really important that we move forward on these utilization projects like Skyonic, like Petronova in which you can take the CO2 and get some positive beneficial use out of it that helps cover the cost of capturing the CO2 in the first place.

CURWOOD: Christopher Smith is Acting Assistant Secretary of Energy. Thank you so much for taking the time today.

SMITH: Hey, thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Skyonic’s website

- Petra Nova’s enhanced oil recovery

- Read more about companies recycling CO2

- The Department of Energy’s Office of Fossil Energy

It’s Tough To Turn Frack Water into Profits

Mike Broeker, COO of Epiphany Solar Water Systems, at his company's facility in Pittsburgh. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier)

CURWOOD: Hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas produces a huge amount of dirty water, and it has to be disposed of, often down an injection well. But a number of businesses are working on technology to clean it up. As the Allegheny Front's Reid Frazier reports, that's a big challenge.

FRAZIER: Inside a big industrial building not far from downtown Pittsburgh, Mike Broeker shows off what he hopes is the next big thing in cleaning up the fracking industry.

BROEKER: We have three 8-foot diameter satellite dishes. These are the most common satellite dishes in the world typically used for radio communications.

FRAZIER: You might say these are no ordinary satellite dishes, but that’s the thing. These are totally ordinary satellite dishes. What Broeker’s company puts on the surface of these dishes. Now, that’s the “not so ordinary” thing going on here.

BROEKER: You can see it here. This has a covering on it, but this is a kind of a vinyl type material that does have some flexibility to it that allows you to get about 95 percent reflectivity.

FRAZIER: That reflectivity is crucial. The company is called Epiphany Solar Water Systems. It uses solar energy to distill clean water. The company was started a few years ago to clean up drinking water in the developing world. But then something else came along.

BROEKER: And then came the Marcellus shale opportunity.

FRAZIER: Each well that’s fracked in the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania produces about a million gallons of dirty water, and you can’t just flush this down the drain. Fracking companies are re-using a lot of this for other frack jobs, or they’re sending it to deep injection wells, often in Ohio. But injection comes with its own problems, like earthquakes. So cleaning the water up could make financial and environmental sense.

FRAZIER: Epiphany re-worked its technology to deal with this fracking waste water. Epiphany’s system uses those satellite dishes and converts them into intense solar heat collectors. Through a series of pipes, it heats up the dirty frack water in a contraption the size of a dorm fridge.

BROEKER: It’s what’s called a mechanical vapor recompression crystallizer.

FRAZIER: It’s basically a still, the same contraption bootleggers use to make moonshine.

BROEKER: The same concept. It is distillation.

REID: They make whiskey but you guys make…

MIKE BROEKER: ...pure water.

Satellite dish panels covered by highly reflective material will collect heat to evaporate water out of oil and gas wastewater. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier)

FRAZIER: Broeker hopes the company’s contraption will be deployed on well pads throughout the Marcellus shale and other places. It’s already got three in the field with different gas companies, though he can’t say which ones. The system is designed to clean up produced water, that’s the water that flows out of a well continuously along with gas and other liquids after it’s been put into production. That water has been sitting underground for hundreds of millions of years, and that makes for a headache to clean up.

BROEKER: You’ve got water that has a tremendous amount of salt in it, about 18 percent salt, by example the ocean has about three to four percent salt.

FRAZIER: Salt destroys equipment, so Epiphany has had to use materials that won’t corrode. The salt also presents a challenge to other technologies Epiphany is competing with. Reverse Osmosis for instance uses a membrane, essentially a filter, to strain the salt out of seawater. To get the water through the membrane, you have to apply pressure to it, but the saltier the water, the more pressure you need.

MAUTER: the issue is that with flowback water and produced water, the salinity is so high you have to push very, very hard, and that risks rupturing the membrane.

FRAZIER: Meagan Mauter is an engineer at Carnegie Mellon University. Mauter’s team has created a special membrane that will allow water vapor to go through it, but no liquids. Dirty water stays back, clean vapor travels through.

[LAB DEMONSTRATION]

MAUTER: Ah, there it goes.

FRAZIER: In her lab at Carnegie Mellon, Mauter shows how the system works.

MAUTER: There is now water coming out of this reservoir, coming in here, across the membrane, and then discharging back there.

FRAZIER: Salty water is heated up and piped to a tiny membrane, a small white semi-circle of plastic cloth. On the other side of the membrane there’s cold water, so through simple condensation, clean water flows out of the system. The key though is getting the membrane just right, Mauter says.

Meagan Mauter, of Carnegie Mellon University, with a high-tech membrane she's developing to take salts out of oil and gas wastewater. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier)

MAUTER: So this particular sample is a millipore membrane. It’s very similar to the polymer that is used to make Gore-Tex.

FRAZIER: Mauter says she’s a long way from having a product that can be commercialized. But if there is ever a machine that can clean up frack water cheaply, some think it will have no shortage of buyers.

FRAZIER: The research firm Lux found the market for waste water treatment from oil and gas is about $1 billion right now, and it could grow to $9 billion by the next decade. But not everyone thinks that these new technologies will ever make money. Brent Giles studies the water market for Lux. He says a lot of startups got into the market thinking they could solve the frack water problem.

GILES: A lot of the start-ups that we see in produced water, in flowback water, are fairly naive, and they’ve got a solution and as soon as they started seeing frack water issues show up in the New York Times and newspapers like that, they kind of did a 180 and decided that they were going to become experts in the oil and gas space, and that hasn’t worked out for a lot of them.

FRAZIER: Why hasn’t it worked out ? Well, Giles says, it’s the water.

GILES: In the Marcellus, most of these technologies, these more advanced technologies have utterly failed to treat the water. It’s such low quality water that the technologies crash and burn when they try to treat it.

FRAZIER: In contrast, companies that use more low-tech solutions, like prepping the wastewater to be re-used in future frack jobs have been much more successful. Part of the problem is that the type and quantity of water produced in oil and gas wells changes over the lifetime of a well. There’s a lot of water that comes out during fracking. After the well is fracked, the well goes into production. During that period, the water that comes out of the well gradually gets saltier and saltier over time. Also there’s a lot less of it than when it’s getting fracked. So creating a technology to treat all those scenarios is difficult. Giles says it’s just cheaper and easier to reuse that frack water or inject it underground.

GILES: Well, we’ve seen a lot of people try, and we’ve seen a lot of people just not meet the numbers the oil and gas people are asking for.

FRAZIER: Broeker of Epiphany Solar Water says his company is already meeting the price point the industry wants. And others say those prices are subject to change. Annie Lane is with the research firm Battelle. Lane is working on a reverse osmosis system that uses multiple membranes.

LANE: The industry’s very interested in potential changes in policy and regulations.

FRAZIER: Lane says she’s getting more interest from oil and gas companies in technologies like hers that can deal with this dirty water.

LANE: They see continued use of injection wells actually as being threatened due to possible changes in policy so they’re interested in identifying alternatives.

FRAZIER: She thinks one day the water will be more valuable cleaned up and above ground, than pumped down a hole. I’m Reid Frazier.

CURWOOD: Reid’s story comes to us from the public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Read more about this story on Allegheny Front’s page

- Epiphany Solar Water Systems

- FracTracker

- Wastewater injection into the ground can cause earthquakes.

- Research estimates oil and gas wastewater management is a $1 billion industry, and could grow to $9 billion by next decade.

- Oil and gas wastewater comes in two basic types—flowback and produced water.

- Meagan Mauter is a chemical engineer at Carnegie Mellon University.

- Epiphany Solar Water has already received a $500,000 investment from Consol Energy.

- Research firm Battelle is working on a reverse osmosis system that uses multiple membranes.

Recycling E-Waste

80% of e-waste in the United States ends up in landfills overseas (Photo: Curtis Palmer; Flickr CC2.0)

CURWOOD: Many of us have clunky old TVs, or obsolete computer clutter. And despite good intentions, chances are when we finally get rid of it, we won’t recycle it, according a survey by Best Buy. And e-waste in the dump can leach toxins into the environment. So some companies including Staples and Best Buy subsidize electronics recycling and take e-waste for free. To find out more, we called up John Shegerian, CEO and Co-Founder of Electronic Recyclers International. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Tell me, first of all, there’s this recent survey from Best Buy which noted that only a third of people, just over a third, actually manage to recycle any of their electronics, though about two-thirds really want to. What gets in the way of actually recycling this old electronic junk?

SHEGERIAN: Well, what gets in the way of most people recycling is apathy, or lack of accessibility or knowledge. But once people know how to recycle, where to recycle, most people want to do the right thing. And recycling rates therefore are rising. Best Buy has seen their volumes go up year after year with their great recycling program, which they pioneered in about 2007. And so, to me, it's very encouraging that retailers like them have created a new recycling paradigm making it accessible for the public at large and they've led on that and others have followed.

PALMER: Yes, I believe Staples as well takes recycling...I don't know who else does.

Guiyu, China is one of the biggest e-waste dumps in the world. Villagers dismantle electronics often in unsafe conditions in search of precious metals (Photo: Bert van Dijk; Flickr CC 2.0)

SHEGERIAN: Well, you're right. Staples and Best Buy are the platinum standard because not only do they take old electronics back, but they also have announced publicly that they only allow responsible recyclers who are certified to touch those electronics, and that's a very, very important point.

PALMER: So when you say you recycle everything, what kinds of things come out, I mean, is there value to be had from these old electronics so that you can actually realize?

SHEGERIAN: Well, there's value to be had, yes. Everything gets commoditized, so you break down electronics into plastics, glass, and metals, and all that material gets sent off to smelters for a new life. The glass costs us money to dispose of, the metals and the plastics we sell.

PALMER: So give me a ballpark figure for what you would actually charge someone for a ton of e-waste.

SHEGERIAN: Twenty-five to thirty-five cents a pound is very typical ballpark figure.

PALMER: So, tell me of a little bit about the irresponsible people. How does it actually come about that actually e-waste ends up going to iresponsible recyclers?

SHEGERIAN: OK. So, if you work for the government or you work for a big corporation, they say, "Hey listen. Your job is to save us money. Your job is to do more with less resources." So now they have a choice. "Hmmm, this one recycler who came in and he quoted me twenty-five cents a pound, I have 100,000 pounds to get rid of - wow - that's going to cost me a lot of money. But there's another recycler down the street, ABC recycling, they said they’d come pick up the stuff for free and just take it off. I'll just call up ABC Recycling." And ABC Recycling comes, picks up the material, and they sell this material to the highest bidder.

Chinese women sort through piles of computer parts (Photo: baselactionnetwork; Flickr CC 2.0)

SHEGERIAN: Back in the early part of 2001, 2002, 2003, the highest bidders typically were the people who wanted to mine the gold, the silver, the precious metals out of the electronics. So they would bring that electronic then, they'd buy it and bring it over to some part of China or some part of India or Africa. They don't have the right tools so they would burn the plastic of the carcass off of it so that would throw a toxic and poisonous gas into the air and then little children typically would be co-opted into the process of doing acid washes to gain the precious metals out of these electronics. Well, first of all there's human rights violations being done by co-opting children into this, and then people would get injured using these acid washes.

SHEGERIAN: That story still continues, but that story has taken on even a darker turn. Now, the highest bidders, in many cases, are people who have adverse interests to our homeland security in the United States who just want to buy the electronics from the government and from large corporations just to pull out the hard drives and reverse engineer the information and then they just dump the carcasses into rivers, lakes, the ocean or the desert. So that's what's happening with still approximately 80 percent of the electronics that we are using in this country are still being shipped off shores and one of those two options are happening to it right now.

John Shegerian is the CEO of Electronic Recyclers International. (Photo: Electronic Recyclers International)

PALMER: But what you do to make sure that, say, my computer when I bring it in - that I have absolutely no idea how to do anything with the hard drive of - what would you do to make sure that none of my data is going to be harvested by anyone, anywhere?

SHEGERIAN: Well it's a great question, and the bottom line is: we've built the world's largest shredders. So your hard drive would go into our shredders for ultimate destruction and then the metals that come out of that would go directly to our smelters.

PALMER: What of the various electronics are the hardest to recycle?

SHEGERIAN: Right now, the hardest things to recycle are tablets because they're built so seamlessly. You know, they're very airtight and built so perfectly they're the hardest today to recycle. They're still recyclable, but they're typically the hardest.

PALMER: So the things that we like about them, their sleek design is exactly what makes them really difficult to recycle?

PALMER: You got it. That's exactly correct.

CURWOOD: John Shegerian is CEO and Co-Founder of Electronic Recyclers International. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- Best Buy’s recycling program

- Staples Recycling Program

- Electronic Recyclers International

CURWOOD: Coming up: using very few words to explain very big ideas. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

[MUSIC: ]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: ]

Beyond the Headlines

Climate change whistleblower, Rick Piltz (Photo: Climate Science Watch)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Off now to Conyers Georgia, to check in with Peter Dykstra, publisher of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org. So, Peter, what’s shaking beyond the headlines today?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve, this past week there were a couple of stories that caught our eye about climate change and political mischief. We learned of the death of Rick Piltz, who was something of a hero in the climate science community for blowing the whistle nine years ago on the Bush Administration’s interference with a US climate science report.

CURWOOD: Yeah, tell us a little more about Rick Piltz. He has an interesting history.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, Rick was a Senior Associate in the Administration’s Global Change Research Program, the White House office that keeps an eye on climate change, from midway in the Clinton Administration to 2005 during the George W. Bush Administration. That year, he quit in protest after learning that a climate science report had been edited and altered to downplay climate change impacts and overplay scientific doubts about how the climate is changing.

CURWOOD: Yeah and as I recall, he became a classic government whistleblower.

DYKSTRA: If there were a government whistleblowers’ Hall of Fame, he’d be in. Rick Piltz turned where a lot of government whistleblowers do, to a group called the Government Accountability Project. Together they took copies of hand-written changes to the science documents to the New York Times, who published them and ignited a little firestorm. Phil Cooney, who had worked his way from being a petroleum industry lobbyist to being Bush’s Chief of Staff at the Council on Environmental Quality, was at the center of the firestorm. Cooney resigned his government job and soon after was hired into ExxonMobil as a lobbyist, where he remains to this day. Rick Piltz went on to run a group and a website called Climate Science Watch, and last year in a video, he said it’s a nonpartisan thing, and here's his quote: “It’s not just one administration. They all need a watchdog.”

CURWOOD: So Rick Piltz fought political interference in science, but you said there’s another story about the same kind of stuff?

The mills of Donora, Pennsylvania, 1910 (Photo: Library of Congress)

DYKSTRA: Yeah and that's going on right now. Two Congressional committees are going after an environmental group for the apparently unfathomable act of communicating with the Environmental Protection Agency. The Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the best-known environmental advocacy groups in the country, stands accused of – er - advocating for the environment. Congressman Darrell Issa, who runs the House Oversight Committee, has taken time from his Benghazi hearings to demand all of NRDC’s correspondence with the EPA over that agency’s rulemaking to limit carbon emissions. He’s joined in this effort by David Vitter, the ranking Republican member of the Senate’s Environment Committee. Both NRDC and EPA say everything’s above board, but the legislators smell a scandal, and when you watch it all unfold, you wish there were more people like Rick Piltz to stand up for science and smart policymaking.

CURWOOD: Well, it does take a lot of courage to be a whistleblower.

DYKSTRA: And it seems courage is in short supply to buck the tide on energy and environment issues, especially during this mid-term election year. Climate change is front and center in only a few election races, like the open US Senate seat in Michigan. The best of the worst is possibly the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology, where, according to Scientific American Magazine, just five of its 22 majority-party members are on record as affirming that climate change is real. That’s the science committee, Steve! And the current line to duck any discussion of climate change is to say “I am not a scientist.” But some of the same folks who beg off any discussion about climate change because they’re not scientists are very, very eager to tell us what to do about Ebola or health care.

CURWOOD: Only in America! Hey listen, can you take us back in the environmental time machine. What’s on the calendar from this week?

DYKSTRA: 66 years ago this week, a weather inversion trapped the industrial town of Donora, Pennsylvania inside a cloud of smog, largely from the town’s zinc smelter and nearby steel mills. 20 people died within hours, an estimated 6,000 people were sickened, as the smoke hung in the air for days.

Downtown Donora today (Photo: Joseph A; Flickr CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yeah, and that was one of the early, most important events in America’s coming to grips with its own air pollution problem.

DYKSTRA: Right and painfully so, not just the health repercussions from pollution, but the town of Donora lost over 5,000 jobs in the next decade as the culprits in the smog disaster, the zinc smelter and steel mills, closed down. Much of the steel industry eventually migrated to places like China, where they’re just now coming to grips with their own Donora-Style disasters.

CURWOOD: Indeed.

DYKSTRA: But one more thought about Donora. Two well-known names from very different fields grew up in Donora around this time. Devra Lee Davis is a toxicologist and environmental health specialist. She was a two year-old at the time of the Donora disaster. And, in a very different field, it was usually left field, was Donora native Stan Musial. By 1948, he was well on his way to becoming one of the greatest baseball players of the 20th century, but Musial’s father, Lukasz Musial, took ill and later died as a result of the Donora Smog Disaster.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Peter.

DYKSTRA: OK. Steve, thanks a lot and we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read the original New York Times story about the Rick Piltz whistleblowing incident

- Andy Revkin remembers Rick Piltz in the New York Times

- Rick Piltz started the organization Climate Science Watch

- Read more about the Donora, Pennsylvania smog incident

- Read more about Republican accusations about the NRDC and the EPA from The Hill

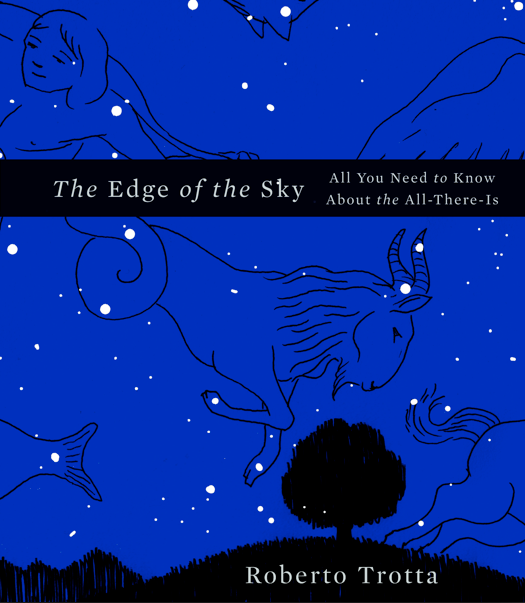

All-There-Is in Ten Hundred Words

CURWOOD: And now, a new book that aims beyond the sky. We’re talking about the universe and cosmology, which most of us at best find confusing. "The Edge of the Sky" by Roberto Trotta aims to simplify and clarify. The book explains the universe in the 1,000 most-used words, or rather, the “all-there is” and “ten-hundred”, since “universe” and “thousand” aren’t on that list. Roberto Trotta studies dark matter and what he calls the “dark push” and the early “all-there-is” at Imperial College in London and joins us. We’re happy to have you on Living on our Home-world, Roberto.

TROTTA: Thank you, Steve. Great to be here.

CURWOOD: What inspired you to use only the 1,000 most common English words to tell the story of the cosmos?

The Edge of the Sky describes our universe (the “All-There-Is”) using only the ten hundred of the most common words in the English language. Since the words “milky” and “way” aren't on the list, author Roberto Trotta refers to our galaxy – or “Star-Crowd” – as the “White Road.” (Photo: ESO/S. Brunier; Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0)

TROTTA: For a decade, I had been looking for new ways of connecting people with cosmology, the study of the universe, and the mystery, and the great sense of wonder that the universe inspires. Then one day something interesting happened to me. I stumbled on an XKCD cartoon - that's a web-based comic series. It was a picture of the Saturn 5 moon rocket, but it was labeled only using the most common 1,000 words in English. So instead of calling it, Saturn 5 moon rocket, it was called the Up-Goer 5 because it's something that goes up, it's a rocket, rocket is not one of the words. So I thought, actually, perhaps, here is a language, here is a format that can be used to get rid of all the jargon that scientists sometimes use to talk about the science, and talk about entire universe, that’s to say the all-there-is, in simple language that anybody can understand.

CURWOOD: So please share with us some of the most surprising words that are on the list, and some other ones that aren't.

Since the words “milky” and “way” are not among the 1,000 most common English words, Trotta used the phrase “White Road” to refer to our home galaxy. (Photo: Steve Jurvetson; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

TROTTA: Well, it was very surprising to me in fact to go to the list and see that fairly common words, like energy, for example, is not on the list. So I couldn't use energy, I couldn't use moon, I couldn't use science, or scientist, or physics, gravity. So all these words that certainly I would have wanted to be able to use to talk about all-there-is...were not on the list. So I had to come up with this new language, this new way of talking about those notions. There were other words that I could make good use of. Thankfully, star was on the list, and so I could talk about planets, which is a word that I couldn't use, as being the "crazy stars" because they go around in a back-and-forth fashion apparently in the sky, so they're like crazy stars. Particle was not one of the words on the list. Television was one of the words. I did use "television" in the book, but it wasn't one of the ones that I necessarily wanted to use.

CURWOOD: So, Roberto, what did you find most difficult to explain using these 1,000 words in the English language.

Trotta used scientific theories, such as those from Albert Einstein, to describe the cosmos. (Photo: Oren Jack Turner; Wikimedia Commons/public domain)

TROTTA: At the beginning, everything was difficult because it was very hard to come up with metaphorical, pictorial images that would explain those sometimes abstract and hard concepts: dark matter, dark energy, the big bang itself, the destiny of the universe...in simple language. But then, little by little, this new voice started to emerge from the format itself, and it grew on me, and things became simpler because I started getting the language, getting the new format, until I got to the point where I wanted to talk about the very early universe, that’s to say the very first fraction of a fraction of a fraction of a second after the big bang, which by the way is not called the big bang because bang is not one of the words. And so, at that point it was very hard because I couldn't use big bang, I couldn't use fraction, to say fraction of a second, I couldn't use particle, I couldn't use energy, all of these important words weren't available. I couldn't use fog. Why would fog be important? well, because the early universe is some kind of high-energy fog. But in the expression, high-energy fog, I didn't have energy and I didn't have fog.

CURWOOD: So what did you choose?

TROTTA: So in the end, I chose a more metaphorical representation of things, and so particles, of which the early universe is full of, became drops. And in particular, I'm talking about the various kinds of drops, that is to say, the kind of particles that inhabited the early universe as if they were characters in a story, and so we meet the simple drops and the very simple drops and the heavy drops and dark matter drops. There's the drop of Mr. Higgs, there are mirror drops. So there's all sorts of characters that populate the story. And it becomes a little bit like a scientific fairy tale if you like.

The “IceCube” Neutrino Observatory, which Trotta depicts as “a huge eye . . . inside the ice, in a cold place near the bottom of our Home-World,” that tries to observe signs of “dark matter drops.” (Photo: Amble, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Now, of course, you're an astrophysicist and you use all kinds of complicated language in your business. How might you now see the universe in a different light having gone through this exercise?

TROTTA: Definitely. Definitely. Writing this book really gave me a new pair of eyes, and a refreshingly different novel look on the universe itself. It forced me to really think about those concepts in a new way. One of the aims of my book was to bring back creativity and passion into science. Science, of course, is a very intellectual sometimes activity, but equally it's important to remember that it's a human activity and as such is full of passion and creativity and the aim of the book is to bring some of that back into the story, and to speak to people's hearts, not to their minds only.

CURWOOD: Who do you want to read this book? Who do you have in mind?

TROTTA: I like to think of the "Edge of the Sky" as a book for children of all ages.

The Large Hadron Collider – or “Big Ring” – accelerates protons to produce new types of particles, which may include dark matter. (Photo: NASA; CC government work)

CURWOOD: Why is it important for you to make science accessible to everyone?

TROTTA: There are many reasons, but let me just talk about two. Science is an expensive business and most of our scientific research, at a fundamental level, the kind of science that I do is paid for by taxpayers' money, and so it's only fair and part of the job of a scientist should be about to spend our time, as professional scientists, some of our time talking to the public and engaging in conversation about why do we need to do this, what are the objectives of the work, why do we need to spend money, taxpayers' money, to do it. But also, another reason for me to talk about science with the general public is that science is a great cultural activity. Science in a way, is akin to the arts. Why do we make great art, why do we enjoy going to museums and experiencing art? Because it makes our lives better, more fuller, more worth living in a sense, and everybody should be able to participate. This is too important a quest to be left to the professional scientist.

CURWOOD: Now, typically when you step into a laboratory, you don't see a lot of women, but in your book, the scientist here is a woman. Why?

Palomar Observatory is anthropomorphized as a character in the book, called “Big-Seer.” (Photo: NASA; CC government work)

TROTTA: Precisely for this reason. Unfortunately women are under-presented in science, certainly in my field, and so I hope by this and other means to help breaking this stereotype that all scientists are middle-aged, old men in white coats with long white beards and a bald patch on their heads. And we need more women in science and if by presenting a scientist as a female character I can help inspire some young girls to be interested in science and to pursue a career in science, then that would be a fantastic result for me.

CURWOOD: Summarize for me in your words, in those 1000 words, what we do need to know about the universe, what you call the all-there-is.

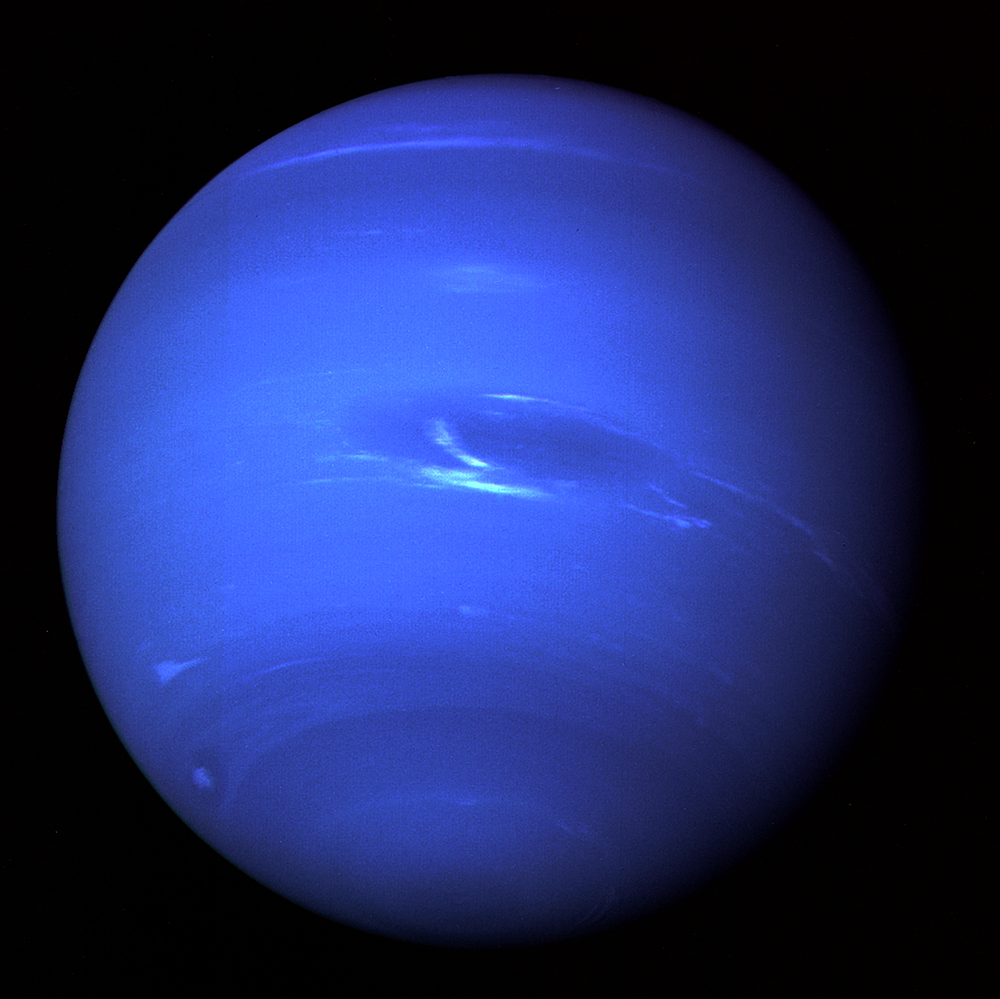

When Trotta tells the history of the planets or “Crazy Stars,” he cannot use the name “Neptune”, instead he writes that it was named after the “Water-God.” (Photo: NASA; CC government work)

TROTTA: There are many things that are still not understood about the all-there-is. For example, the big why questions that certain people are asking nowadays are, What is dark matter made of? What is the dark push made of that is making the all-there-is gro faster and faster with time? And we have learned there is 20 times more dark matter than dark push in the all-there-is than there is normal matter, and we don't understand it. Most of the all-there-is is unknown, and we really don't know what it is made of. So those are the biggest questions that certain people like myself are asking today and we hope to find out answers that will help us understand our place in the all-there-is.

CURWOOD: Roberto, chapter 8 of your book ends with a profound statement about the ever-increasing expansion of the universe the all-there-is. Please read that passage for us.

TROTTA: You can't stop the dark push. All of the star crowds will fly away from us faster and faster, until at some point, far away in time, we won't be able to see them anymore. They will be too far away for the light to reach us. Stars will die, and the star crowds will turn off. The all-there-is will become even bigger and almost totally empty. Nothing will be left but dark silence.

CURWOOD: So, how ultimately terrifying is this idea that the universe will eventually become dark silence?

“Moon” is not one of the ten hundred most common English words; in The Edge of the Sky, our “Home-World’s” satellite becomes “Sun’s Sister.” (Photo: Stephen Rahn; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

TROTTA: It is terrifying intellectually, but not as much as the prospect of...the many threats that are closer to home and closer to us in time: climate change, epidemics, all sorts of threats that are threatening us as humans in a more direct and more timely fashion. But certainly if we think about the great grand scheme of things, and the great picture of the cosmos that emerges, thinking of a universe that's going to be empty and dark, is pretty scary.

CURWOOD: By the way, Roberto, in your book, you touch on the multiverse theory. Talk a little bit about that for me now and how we could try to understand that.

TROTTA: The multiverse theory is something very speculative. We have no idea whether any of this really exists out there, but in the book, I talk about it in very simple language. I talk about a room full of coins, a table where we find 400 coins, that are all showing heads. And so if you were to walk into such a room, you'd certainly think that somebody's been there before you and has put down all the 400 coins heads up just like that, and you wouldn't imagine for a second that they've all been thrown up and just landed at random, all heads up. And yet, the universe we happen to live in is as improbable as getting 400 heads out of 400 coins all at once, which is a tiny tiny probability. It's almost zero.

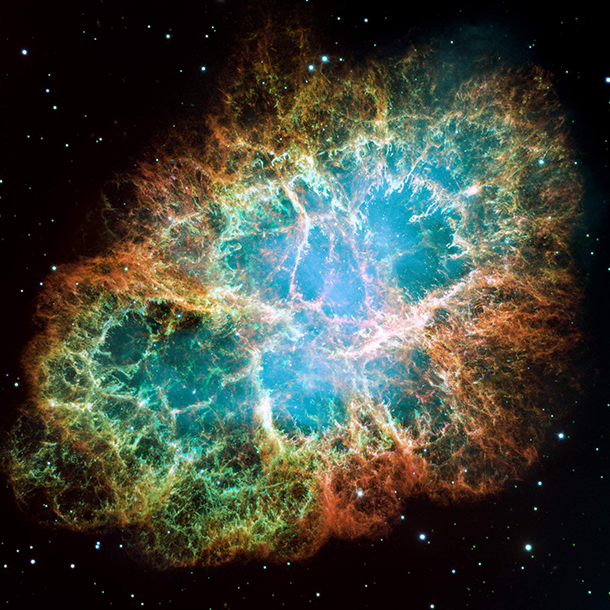

In Trotta’s book, the term supernovae is translated to “Dying Stars.” (Photo: NASA; CC government work)

TROTTA: And so the big question is: "Why is our universe specifically strange. Why is it so improbable?" And perhaps the idea is that the dark push, the mystery of the dark push has something to do with it, and a tentative explanation that some scientists are beginning to give is that perhaps it's a question of just having many many rooms having many many flips of the 400 coins and sooner or later you end up with one room that has all of the 400 coins in it showing heads up, just like that, just by the laws of chance, it’s only a question of having enough rooms, and that's to say, having enough universes in the multiverse, a collection of many many many different universes, and we will live in one that's just right for us, one that's very improbable, but that happened just by chance.

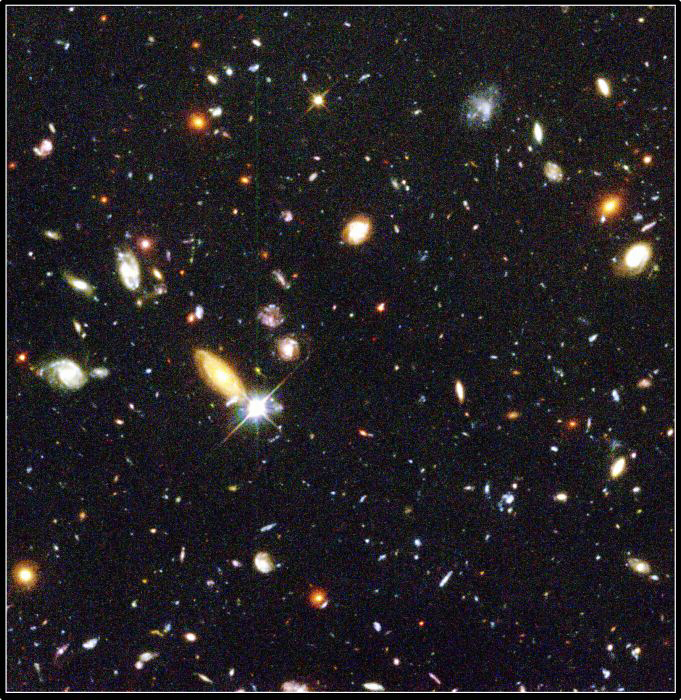

“Star-Crowds,” or galaxies, typically contain about a hundred billion stars, lots of gas, and even more dark matter, Trotta writes in his book. (Photo: NASA; CC government work)

CURWOOD: Some people listening to us will say, well, either this all came from a cosmic roll of the dice or a flip of a coin, as you say, or maybe there's God involved. What do you say?

TROTTA: Well, certainly, that's...there will always be this question, science, even with the tentative explanation of the multi-verse is ultimately silent about the meaning of physics, the meaning of the universe and the meaning of facts. And so the meaning of all our scientific discoveries is the ultimate fundamental meaning of reality, and the Why are we here? questions are questions that science cannot methodologically answer, so it remains for each individual to find meaning and a sense of direction in their lives in any way that's meaningful to them.

Roberto Trotta is an astrophysicist at Imperial College London. (Photo: Courtesy of Roberto Trotta)

CURWOOD: Before you go, your favorite star?

TROTTA: My favorite star hasn't been discovered yet. It's probably a dark star in a dark nebula made of dark matter.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Roberto Trotta studies dark matter, dark energy, and the early universe as an astrophysicist at Imperial College in London. Professor Trotta, thanks so much for your time today.

TROTTA: Thank you, Steve. Great pleasure talking to you.

Related links:

- The 1,000 most common words in the English language

- The original xkcd.com “Up Goer Five” webcomic explaining a space shuttle in 1,000 words

- Edit text for the 1,000 most common words in the English language

[MUSIC: ]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of the team. Our show was engineered by James Curwood with help from Karlyn Daigle. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us please on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth