November 7, 2014

Air Date: November 7, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Green At the 2014 Ballot Box

/ Peter Dykstra, Helen Palmer, Emmett Fitzgerald, Naomi ArenbergView the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra assess some environmental lessons from the 2014 midterm elections, discussing the effects of money spent by green activists, its effect on the races and some of those who lost their jobs. Also, Living on Earth reporters round up the fate of energy and environmental ballot initiatives. (13:20)

Arsenic Released in Frackwater Spills

/ Reid FrazierView the page for this story

Frackwater contains many toxic elements and chemicals that contaminate groundwater if it spills. As the Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier reports that when it spills, microbes start to clean it up, but the process can release arsenic which also pollutes groundwater. (07:50)

Fingerprinting Frackwater

View the page for this story

Determining the source of water contamination in the environment is tricky, as many industrial pollutants are similar to naturally occurring chemicals. A recently developed method of “water forensics” could help determine if a frackwater spill is the culprit. Robert Jackson of Stanford University explains this new method to Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald and describes why it’s important to pinpoint the source of environmental pollutants. (06:15)

Hyundai and Kia Fined for Misreporting MPG and Greenhouse Gas Emissions

View the page for this story

The EPA and Justice Department fined Korean automakers Hyundai and Kia for under-reporting their fleets’ greenhouse gas emissions in violation of the Clean Air Act. Host Steve Curwood discusses the fines and restitution the automakers must pay with Dave Cooke, a vehicle energy analyst for the Union of Concerned Scientists. (05:30)

Restoring California’s Giant Kelp Forests

View the page for this story

California’s giant kelp forests were mostly wiped out by ecosystem imbalances, but a decades long year citizen science effort has helped restore them. Host Steve Curwood speaks with marine biologist Nancy Caruso about the fragile ecosystem, the restoration she led and California’s majestic kelp forests. (11:45)

Uprooting an Invasive Ribbon Grass on the Metolius River

/ Courtney FlattView the page for this story

Ribbon Grass growing along Oregon’s Metolius River is attractive, but the invasive plant has edged out acres of native sedges and wildflowers. EarthFix’s Courtney Flatt reports that how locals and state groups are pulling out and poisoning the weed to protect the river’s ecosystem. (03:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Robert Jackson, Dave Cooke, Nancy Caruso

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Naomi Arenberg, Helen Palmer, Emmett Fitzgerald, Reid Frazier, Courtney Flatt

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. As Capitol Hill swings Republican in the wake of the elections, we assess the influence of cash on candidates and green ballot initiatives, and the outlook for the much-stalled Keystone XL pipeline to bring Canadian tar sands oil to Gulf Coast refineries. Also, pollution detectives are fingerprinting dirty water.

JACKSON: We use the isotopic signatures and the ratios of different elements to distinguish between conventional wastewater from oil and gas wells, and the newer hydraulically fractured wells.

CURWOOD: Forensic chemistry to solve fracking water mysteries, and the back-breaking task of yanking a pretty but invasive grass from a river by hand.

SCHAY: It’s very heavy. It’s mostly water. It’s 99 percent water that you’re pulling...dragging around.

CURWOOD: Wrestling with ribbon grass and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

Green At the 2014 Ballot Box

On Tuesday November 4th, 2014, Americans around the country voted in the midterm elections. Millennial voters (under 30 years old) accounted for only 12% of the turnout. (Photo: Joe Shlabotnik; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. While many news organizations look at the recent elections in terms of blue and red — Democrat and Republican — we consider the results in terms of green—how the voting relates to environmental concerns. It turns out that in 2014 there were plenty of environmental measures on ballots across America, and we’ll have more on them in just a few minutes. But right now we turn to the Daily Climate’s Peter Dykstra for an ecological assessment of the races. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. It definitely was a clear message in this election. And after unprecedented spending by the environmental side, and unprecedentedly strong organization by environmental groups in the election campaign there’s very little to show for it from Tuesday’s election. Anybody who cares about such things already knows the headlines – the Republican Party reclaimed a majority in the Senate, Democrats lost some presumably safe Governors races, and more.

CURWOOD: Right, and all that spending you mentioned came from deep-pocketed activists like Tom Steyer. And you wrote about this in The Daily Climate before the election.

Mitch McConnell is the likely new Senate Majority Leader and a re-elected Republican Senator from Kentucky. (Photo: Official Senate portrait/US Congress)

DYKSTRA: I did, and Tom Steyer is the venture capitalist turned political force on climate and other green issues. It made for an interesting story, but it’s one that inside-the-beltway journalists consistently got wrong. There were numerous pre-election stories pairing Steyer against the much, much deeper pockets of the Koch Brothers. It created a nice narrative but a false balance, and some people fell for the line that the political power of Big Oil had finally met its match in the political power of Big Green. It’s not gonna happen any time soon, folks. The power and reach on the environmental side can’t begin to match the dough behind the anti-science, anti-regulatory, anti-environment causes. And to me, there’s one example of this that makes a far more interesting story than either the Kochs or Tom Steyer.

CURWOOD: Oh, and who’s that?

DYKSTRA: Joe Ricketts, the founder of TD Ameritrade, co-owner of the Chicago Cubs and the money behind a PAC called EndingSpending. Ricketts focused millions on Senate races much of it on Michigan, New Hampshire, and Georgia. In particular, the Michigan race ads criticized Gary Peters over the Keystone XL Pipeline. He also ran attack ads against Jeanne Shaheen in New Hampshire and Michelle Nunn in Georgia, all Democrats. Nunn lost, but Peters and Shaheen were two of the Democrats’ bright spots, so Joe Ricketts, in the fashion of his Chicago Cubs, lost two out of three.

CURWOOD: OK, Peter, but let’s stay with the Keystone pipeline for a moment. Republicans have made approval of this pipeline to carry tar sands oil from Canada to refineries along the Gulf of Mexico a top priority.

Many seats in the US Senate and House of Representatives were up for grabs in the 2014 midterm electoral race. (Photo: Rob Crawley; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Yes, and in their victory speeches this week the new Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Republican Party Chair Reince Preibus made it clear that they’ll push for Keystone even as some in the oil industry seem to be backing away from tar sands. Meanwhile, out in Nebraska where there’s a pitched battle over Keystone, one of its biggest Congressional boosters lost a close race: Lee Terry, an eight-term Republican, was surprised by a challenge from Democrat Brad Ashford.

But in reality, control of the Senate might be more symbolic than anything else, though. The Republican-controlled House the past few years has gotten obsessive over things like Obamacare, passing the same repeal bill over and over again, knowing full well that it won’t survive the Senate or a Presidential veto. The Senate may now jump into the same trench, passing symbolic bills to de-fund or maybe even abolish EPA, to build Keystone, and other environmental issues.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but, Peter, you just pointed out that Obama has that veto pen.

DYKSTRA: Yes, and the risk is that this election sends a message that the Democrats didn’t see much positive, and the increasingly environmentally-hostile Republicans didn’t see much of a downside, in taking sides on the environment. If President Obama reads those political tea leaves, the Keystone pipeline is as good as built. But if, like a lot of second-term Presidents, he wants to leave a legacy that in this case includes climate change action, he might kill the pipeline or leave it in the lap of the next President.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Come back a little later in the show and we’ll talk a few election day specifics.

DYKSTRA: OK.

Democrat Tom Udall ran for Senate reelection in New Mexico and won. His cousin, Mark Udall, ran in Colorado, but lost to Congressman Cory Gardner. The Udall family is known for supporting environmentally-friendly legislation that protects natural resources and promotes renewable energy. (Photo: US Senate)

CURWOOD: There were environmental initiatives on the ballot in some states, but not much of a pattern to the results. Maine and Michigan took on hunting. In Maine, voters said it’s ok for hunters to use bait when hunting bears, but Michigan rejected wolf hunting in a vote that’s likely to end up in court as the legislature had already approved that method of population control. Massachusetts refused to extend container deposits to bottled water, while Berkeley, California, approved a soda tax. And the question of labelling GMO ingredients was back again – Living on Earth’s Naomi Arenberg has been looking at what happened.

ARENBERG: There were two statewide referenda to require GMO labeling, each of which failed. In Colorado 66-percent weighed in against Proposition 105, as opposed to only 34 percent in favor. The vote in Oregon, though, was so close that Measure 92 was not decided until Wednesday afternoon, and then with less than 51 percent bringing it down. I might add, Steve, that both sides broke spending records for Oregon ballot measures.

CURWOOD: Interesting. So what about the other two GMO-related votes?

ARENBERG: These were countywide initiatives. Northern California’s Humboldt County has – I’m quoting, here – prohibited “the propagation, cultivation, raising, or growing of genetically modified organisms.” Farming is not the big business in Humboldt that it is in other parts of California. That said, the other successful measure WAS in an important agricultural region. Maui County in Hawaii might be best known as a tourist destination, but actually it’s an important agribusiness research center for Monsanto and Dow, and that’s for the same reason it’s a vacation spot—weather. The growing season lasts all year long, and both Dow AgroSciences and Monsanto are heavily invested in seed development there.

Tom Steyer is a venture capitalist, philanthropist and environmentalist. He donated large sums of money to environmentally-minded politicians running in the 2104 elections. (Photo: Helloaloe; Wikimedia Commons SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Naomi, you mentioned big money involved in Oregon’s close vote. What about Maui?

ARENBERG: Well, we know that GMO supporters spent nearly $8 million, or over $300 for every vote against the ban.

CURWOOD: And all that money wasn’t enough?

ARENBERG: Nuh uh, but it was very close. The ban passed by only a couple of percentage points. It seems like grassroots organizing made the difference. Residents in Maui County took to the streets, carried signs, knocked on doors, and they called friends to talk about Monsanto’s and Dow’s agricultural practices.

CURWOOD: So what exactly did the “yes” voters get?

ARENBERG: They got a temporary ban on genetically engineered crops, which stays in effect until the county council reviews safety studies, to determine the potential environmental or health threats of GMO plants. And the research is being paid for – are you ready for this Steve? – by the seed companies.

CURWOOD: Why am I not surprised? Thanks, Naomi.

Well other ballot questions took on land use and the protection of natural resources. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer has been checking up on them.

PALMER: Yes, several states had these issues on the ballot - New Jersey, Florida, North Dakota, Louisiana, Alaska. Most of the initiatives were successful. Florida’s Amendment 1, to devote a third of excise taxes to wildlife, fish, forests and the like; Louisiana’s Amendment 8 that ensures the money in the state’s Artifical Reef Fund really goes to building reefs in the Gulf; and in New Jersey, voters approved an amendment to guarantee funding to buy and preserve open space and farmland.

CURWOOD: Those also sound very green.

Massachusetts refused to extend container deposits to bottled water. Berkeley California approved a soda tax. (Photo: Nick; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

PALMER: Yes, but some environmentalists worry that the New Jersey measure could drain money from other environmental priorities, like cleaning up toxic waste sites in the Garden State. North Dakota’s Measure 5 would have devoted some oil revenue to clean water, parks and wildlife, but it was thumbs down for that. And Maine and Rhode Island passed successful bond measures for water, wetlands, and other environmental projects, and two thirds of Californians voted to devote over $7 billion to improving the golden state’s water supply and quality.

CURWOOD: Nothing like a drought to concentrate the mind, and loosen the purse strings.

PALMER: Yes, and finally Alaskans voted to give the state legislature greater veto power over mining projects in Bristol Bay. You’ll remember Steve, that’s where the controversial Pebble Mine is proposed, and critics say that threatens the Bay’s massive salmon fishery.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Helen.

PALMER: Sure.

CURWOOD: Now there were a number of bans on hydraulic fracturing for natural gas on the ballots. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald has been following those.

FITZGERALD: Yeah, the one that’s getting the most attention is Denton, Texas, where 59 percent of the electorate voted to ban fracking from the city. It’s a pretty shocking result when you consider that Denton is a solidly Republican town in the middle of the Barnett Shale formation, where fracking technology was first developed. The oil industry spent nearly $700,000 fighting the bill, but they were defeated by a grassroots campaign of locals who were tired of the noise and the fumes from over 270 natural gas wells operating within city limits. Anti-fracking activists around the country are hailing this as a victory in the heart of oil country.

Corn is a crop that agricultural companies often genetically modify. There were two, state-wide referenda to require GMO labeling in Colorado and Oregon, both of the measures failed. Two other county-wide initiatives in California passed that prohibit, “the propagation, cultivation, raising, or growing of genetically modified organisms.” And Maui, Hawai’i voted in a temporary moratorium on all genetically modified crop production until the local council is satisfied with safety testing. (Photo: Dodo-Bird; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hmmmm...now, where else was fracking voted on in this election?

FITZGERALD: Four towns in Ohio voted on fracking bans, although only one actually passed, that was Athens, Ohio. And then there was California. Earlier this year the California senate narrowly rejected a statewide moratorium on fracking, but in this election it was back on the ballot in a number of counties. San Benito and Mendocino Counties voted to ban fracking, while Santa Barbara voters gave it the go-ahead.

CURWOOD: Now, I hear there was another interesting local race in California, tell me what happened in Richmond.

FITZGERALD: Well during this campaign cycle the oil company Chevron poured $3 million dollars into local races there. A lot of that money went to ads attacking politicians who have been critical of Chevron’s refinery in Richmond. The refinery is the largest employer in the city, but many people are concerned about safety standards and the impacts on public health. A fire at the refinery in 2012 sent 15,000 Richmond residents to the hospital with respiratory problems. In their effort to elect industry-friendly candidates Chevron created its own local media outlet, the Richmond Standard, which pumped out pro-refinery stories throughout the election cycle. But in the end this elaborate and expensive strategy backfired, as the city elected a slate of progressive refinery critics, including new mayor Tom Butt.

Many ballot measures in the 2014 midterm election helped buy and preserve land and protect natural resources. Florida’s Amendment 1 devoted a third of excise taxes to wildlife, fish, forests; while Louisiana’s Amendment 8 delegates money from the state’s Artificial Reef Fund to building reefs in the Gulf. New Jersey voters approved an amendment to guarantee funding to buy and preserve open space and farmland. (Photo: Marc AuMarc; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Thanks, Emmett, and we’ll get back to you later in the program with more about fracking.

But now Peter Dykstra joins us again with more observations on the midterm elections and the environment. Peter, there was some big news for an American political/environmental dynasty last Tuesday, huh?

DYKSTRA: There was. Mark Udall lost a close re-election bid to Colorado Congressman Cory Gardner. His cousin Tom Udall won re-election to the senate in New Mexico. Their respective Dads, Mo and Stewart Udall, were environmental champions in the last half of the 20th Century, Mo as a Congressman and Presidential candidate, Stewart as Interior Secretary for Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. But Mark Udall’s defeat was one of the bigger Senate losses for the Democrats, it was far from the only one though.

CURWOOD: Hey, Peter, let’s talk a bit more about something you mentioned earlier. There doesn’t seem to have been a downside for members of Congress who are downright hostile to environmental protection.

DYKSTRA: Senator Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma, who has called climate change a “hoax,” had token opposition and won re-election by almost 40 percentage points. Lamar Smith, the Chair of the House Science Committee who calls himself a skeptic on climate change but actually he talks a pretty good denial game too, ran unopposed. Now both the Senate and House committees that deal with science, environment and climate will be chaired by folks who just can’t be bothered with science.

Alaskans voted to give the state legislature greater veto power over mining projects in Bristol Bay, where the controversial Pebble mine is proposed. Critics say that the mine threatens the Bay’s salmon fishery. (Photo: Chris Ford; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

And while some fierce environmental opponents got through without serious election opponents, even some Democrats ran their campaigns like they’d rather be photographed next to a railcar full of hydrocarbons than next to Barack Obama. Alison Lundergan Grimes tried to out-coal Mitch McConnell to score votes in pro-coal eastern Kentucky, but McConnell ended up winning easily. In Louisiana, Senator Mary Landrieu – another defender of hydrocarbons on the Democrat side - finished second and faces an uphill fight in a run-off vote next month.

CURWOOD: So, is it retrenchment all the way for environmental priorities?

DYKSTRA: Quite possibly. But a couple of numbers about this election really struck me. First, by now I’m sure we’re all already missing the flood of blood-curdling attack ads. The Center for Public Integrity calculated that the US Senate races alone spawned - get this number - 908,000 TV ad placements. And that’s just the broadcast stations, it doesn’t include cable TV. That’s a lot of money, drawn out of big spenders, courted by politicians, then distributed to campaign consultants and TV stations. It doesn’t matter what your politics are, it’s no way to run a democracy.

But here’s another one: NBC News polling said that millennial voters – voters under 30 – were only 12 percent of the turnout on Tuesday. Just two years ago, under-30 voters were 19 percent of the total. If you’re pushing environmental issues and young voters don’t show up, you’re in trouble. And what do you think the exit polling told us about climate change this week?

Hydraulic fracturing for natural gas was on the 2014 midterm ballot for many counties around the nation; Denton, Texas was one of several jurisdictions, which voted to ban it. (Photo: Daniel Foster; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: What’s that, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Nothing! There isn’t any exit polling on climate change - what are you, crazy? It’s not that important to the pollsters. Actually, the Associated Press exit polls said climate change is on many voters’ minds, but the results don’t suggest it was on their ballots.

CURWOOD: Thanks so much, Peter. Peter Dykstra is the publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much Peter, talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

Related links:

- Tom Steyer’s pro-climate action campaign funding didn’t match the Koch’s Big Oil money

- Chevron poured money into a local Richmond, California election with no payoff

- Outcomes of several climate and energy ballot initiatives from the 2014 midterm race

- Lawsuit planned after Maui County voters approve temporary GMO ban

- Texas Town's Fracking Ban Draws Legal Challenge From Energy Group

- Food votes: GMO labels rejected in Colorado and Oregon; Berkeley taxes soda

- Follow energy and environmental ballot measures by topic on Ballotpedia

[MUSIC: Marcia Salomon from “Quando O Carnaval Chegar” from Putumayo Presents Brazilian Café (Putumayo 2009)]

CURWOOD: And coming up...The biggest fine ever under the Clean Air Act – for fudging mpg [miles per gallon]. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: James Cartert from “’Round Midnight” from The Real Quietstorm (Atlantic 1995)]

Arsenic Released in Frackwater Spills

U.S. Geological Survey researcher Denise Akob holds vials filled with iron minerals. The vial on the right contains sediment from a stream contaminated with oil and gas waste, and has turned black because of bacterial reactions with the sediment. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Well, though some states and jurisdictions launched ballot measures to restrict hydraulic fracturing, there are still over a million oil and gas wells nationwide, many with new life thanks to the technique of fracking. And the huge amounts of noxious wastewater from frack wells remain a problem. One firm recently got slapped with a record fine after contaminated frack water leaked out of storage ponds in Pennsylvania. And as Reid Frazier reports, people living near the gas wells as well as scientists are asking what exactly is in all this wastewater and how is it changing the environment.

FRAZIER: Denise Akob is a microbiologist for the US Geological Survey. In a USGS lab outside of Washington, DC, she holds up a glass jar filled with water. At the bottom of the jar is what looks like sand.

AKOB: It’s got this brown color, it’s rocky, the water still really clear.

FRAZIER: The sediment is from a clean streambed. It’s been inside the bottle for 90 days. Akob holds up a second bottle. This one’s not so clear. Inside of it is sand a from a stream in West Virginia that was polluted by a leaking oil and gas wastewater impoundment.

AKOB: You actually can’t even see through the bottle.

FRAZIER: An orange goo coats the sides of the second bottle. The goo is iron oxide--rust. It’s the result of a chemical reaction between microbes in the sediment and contamination in the streambed. The experiment is part of a research project at the USGS to determine the risk posed by fracking wastewater. The oil and gas industry produces billions of gallons of this waste every year. It’s the briny liquid that comes out of a well after it’s been hydraulically fractured with millions of gallons of water. The waste is tainted with chemicals from fracking fluid, and has toxic levels of metals and salts from underground formations.

COZZARELLI: One of the main things we’re trying to do on this project is identify what the important potential pathways to the environment are.

FRAZIER: Isabelle Cozzarelli is a geochemist leading the team of USGS researchers.

COZZARELLI: So there can be accidental spills, there can be leaks or spills at waste disposal facilities.

Sediment from a stream impacted by fracking wastewater develop orange residues after 90 days, while sediment from a clean stream did not. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier)

FRAZIER: In North Dakota, a million gallons spilled from a pipeline break earlier this year and killed a swath of vegetation along its two-mile path.

Cozzarelli’s team is looking closely at one question - what happens when tiny organisms in the soil come in contact with frackwater. These bugs are like the Earth’s gut bacteria.

COZZARELLI: I guess you could call it the microbial flora, right?

FRAZIER: So they’re studying the everyday behaviors of these microorganisms.

COZZARELLI: And, so they have to do two things, right? They need food and they need to breathe.

FRAZIER: And some bacteria eat crude oil and chemicals found in oil and gas waste. So if some it spills on the ground, it’s like an all you can eat buffet for bacteria. That seems like good news right? The bugs can eat the contamination. But there is a catch. These bugs need to breathe, too. And they need to breathe more when they’re given a large new food source, like a frackwater sprill. But underground, there is very little oxygen. Cozzarelli’s group says the bacteria they study evolved to thrive in this inhospitable environment.

COZZARELLI: And if you’re a human, you die, right? [LAUGHS] But if you’re a cool microorganism you can breathe the nitrate or the iron or the sulfate. Because you’ve adapted to be able to do that.

FRAZIER: That’s right. These bacteria don’t need oxygen to breathe. They can even breathe in metals, like iron. Here’s where the problem starts though. The more food they get from a spill, the more iron they breathe. Iron minerals found in soil are a frequent host for another element - arsenic, a known human carcinogen. When a bacteria breathes that iron in, the arsenic is released, and becomes water soluble.

COZZARELLI: And you can get more arsenic released into groundwater.

FRAZIER: That's what it appears happened at an oil spill site in Minnesota. Arsenic levels in the groundwater there are 20 times above the EPA limit for drinking water, though no one is actually drinking that water. So will bacteria help or hurt groundwater quality when frackwater gets on the ground? Cozzarelli says they’re just beginning to answer these questions.

COZZARELLI: I kind of feel like we’re trying to catch up...the industry’s just gone so quick.

FRAZIER: All this science could help in states where frackwater spills occur. In Pennsylvania, oil and gas companies have drilled 8,000 wells in the Marcellus shale. And state records show that spills or leaks of fracking waste are common. The mapping website FracTracker analyzed violations records from the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. It found 53 recorded spills of fracking wastewater so far in 2014; that's more than one a week. Many of these are small, only a few gallons, but some are not.

[DIESEL TRUCKS PULLING IN]

FRAZIER: In Washington County, in southwestern Pennsylvania, trucks removed contaminated soil from a hillside that used to house a wastewater pond. The John Day impoundment was ordered closed this year after the company that owns it, Range Resources, discovered high salt levels in the soil beneath its liner. The DEP found Range had leaks at several of its waste ponds in the area. In September, the company agreed to pay a record $4.15 million fine for these discharges.

FRAZIER: Range said in a statement it was disappointed by the violations, but said safety features at its new impoundments would go above and beyond DEP requirements. The DEP’s Scott Perry said the size of the fine reflects how seriously the state is taking the issue.

PERRY: Management of wastewater from oil and gas development is, in my opinion, the most critical environmental issue associated with the activity. Perry said the state is beefing up its rules on impoundments, which could include mandating two liners below each waste pit. That’s welcome news for residents like Janice Dumont. She lives next to one of the leaky impoundments, this one in Cecil Township, just south of Pittsburgh.

At her house, contractors are putting on new siding. The upgrades came courtesy of money Dumont and her husband received from Range Resources for a gas lease on their land. But word of a potential leak at the impoundment nearby has caused her to worry about groundwater.

The John Day impoundment in Washington County, Pa. Range Resources excavated contaminated soil after it discovered a leak at the site. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier)

DUMONT: Range tested it, the DEP tested it, and there was no impact from the fracking pond.

FRAZIER: To see the leaky impoundment, all Dumont needs to take a ride on a cart.

[OUTDOORS WITH WIND BLOWING]

DUMONT: [LAUGHS] I got this for my 40th anniversary. It’s called a gator, a John Deere Gator.

[MOTOR STARTS]

FRAZIER: At the top of a steep hill, on the left, she points out the waste pit, which has been taken out of production. It’s cut into a hillside.

DUMONT: That was such beautiful farmland before...I guess it will be again...looks like a strip mine.

FRAZIER: A steep ravine separates her hill from the impoundment. She says a DEP inspector told her the ravine might act as barrier between pollution from the waste pond and her groundwater.

DUMONT: We were just fortunate, I think. We were lucky that we didn’t have any problems. Because our well water is so good. I mean it’s delicious, it’s cold, and there’s no water bills.

FRAZIER: Range Resources will keep testing the groundwater, and will remove the impoundment by next year. Dumont says she won’t miss it.

I'm Reid Frazier.

CURWOOD: Reid reports for the public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Learn more about Fracking wastewater spills on the Allegheny Front’s page

- Our story on iron-eating bacteria

- U.S. Geological Survey

- In North Dakota, a million gallons of brine spilled from a wastewater pipeline break earlier this year and killed a swath of vegetation along its 2-mile path.

- Arsenic levels in an aquifer near Bemidji, Minnesota are 20 times above the EPA limit for drinking water, thanks to microorganisms’ chemical reactions.

- In Pennsylvania, oil and gas companies have drilled more than 8,500 wells in the Marcellus shale.

- FracTracker analyzed oil and gas violations records from the DEP and found 214 recorded spills in 2014; 53 were for oil and gas wastewater.

- In September, the Range Resources company agreed to pay a record $4.15 million fine for waste pond discharges.

- Range’s statement concerning the violations and its new impoundments

- The DEP is also attempting to fine The EQT Corporation $4.5 million for leaks at a 6-million gallon wastewater impoundment in northern Pennsylvania.

- EQT is challenging the fine, calling it “exorbitant.”

Fingerprinting Frackwater

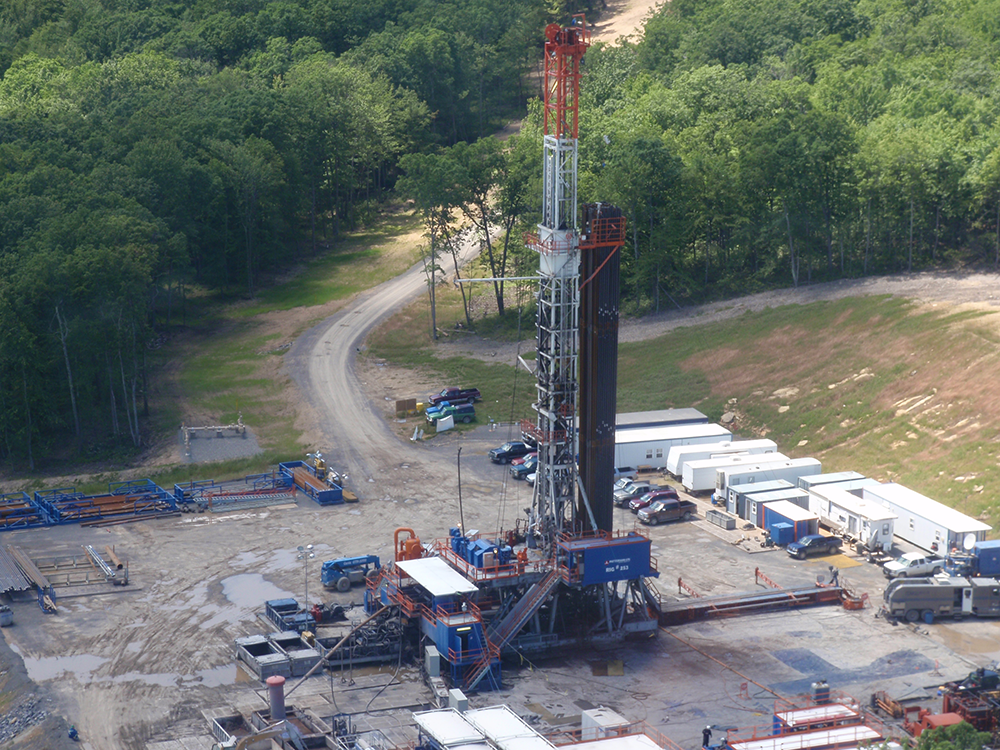

An aerial view of a wastewater pond located in the Marcellus Shale, Pennsylvania. (Photo: Prof. Robert Jackson)

CURWOOD: Now, as he was explaining, pinpointing the precise source of groundwater contamination can be tough. Many fracking chemicals are naturally occurring, or are used in other industries. But a study just published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology lays out a new forensic approach to help track down the exact source of fracking water pollution. One of the authors is Robert Jackson, who teaches at Stanford University. He explained this new technique for frackwater detecting to Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald.

FITZGERALD: So tell me about a little bit about what you’ve done, about your study, and how that's addressing some of these problems.

JACKSON: Well, for a number years now, we've been interested in tracing the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing fluids and also elements found naturally deep underground that might contaminate groundwater. That contamination could occur through a well that's made improperly or poorly, but it can also happen if wastewater leaks out into the environment. And oil and gas operations in United States generate a trillion gallons of wastewater every year. There's a lot of it.

Diagram of location of conventional and unconventional oil and gas reservoirs in ground formations. Fracking (drilling and pumping large quantities of chemical-laden water underground) helps access these reserves. Fracking fluids and water flow back to the surface carrying native chemicals and elements from the surrounding rock and clay formations. These chemicals and element ratios give each fracking wastewater source a specific analytical signature that can be used to identify it in the case of a spill. (Photo: Wyoming State Geological Survey)

FITZGERALD: So tell me a little bit about the work that you're doing, and how you're able to determine whether water has fracking fluids present in it.

JACKSON: Well, in this paper we focused on a handful of elememts. Boron, lithium, in particular, but also salts, such as chloride, and even bromide. And we're focusing on these elements because some of them are added into hydraulic fracturing fluids - boron in particular - but all these things are found naturally deep underground. When the company pumps water deep underground to extract the oil and gas, some of that water flows back to the surface. When it does it carries those elements back with them, sometimes in very high concentrations. In the Marcellus [shale region], for instance, the water that comes back out of the well might be 10 times saltier than seawater, and so if that water that is produced out of the oil and gas well leaks onto the surface, then we can use the presence of these elements and their chemical signatures, the isotopes, to identify them.

FITZGERALD: So you call boron and lithium, in particular, tracers. What you mean by tracers?

A drilling rig in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale. There are over 1.1 million active oil and gas wells in the U.S., and over a trillion tons of fracking wastewater is generated in a year. (Photo: Prof. Robert Jackson)

JACKSON: A tracer is a compound that you can use to tell different sources apart. So when I talk about a tracer I'm thinking about something that might be found in different concentrations in different sources. It might be found in one source but not the other at all, or it might have a different chemical signature like its isotopic composition. So these compounds allow us, even at very low concentrations, to identify the source in the environment. So I'll give you an example. A few years ago, in the the Monongahela River in Ohio and downstream there was this really big controversy about increases in bromine and other salts in the river water potentially impacting people's drinking water, and there was a lot of discussion about what the source of that was. Was it old coal mines, was it conventional oil and gas wells, or was it the newly hydraulic fracturing wells that were popping up all over the place in the watershed, or at least in the wastewater that was being brought to the watershed?

JACKSON: So this kind of approach allows us to disentangle, to distinguish those kinds of situations. We can separate different waste streams and tag them back to their source.

Truckers ship fracking wastewater around the country for clean-up and processing. (Photo: Prof. Robert Jackson)

FITZGERALD: So basically you're looking at the chemical, the presence, the concentration, the isotopic situation with these different compounds and indirectly you’re able to say well this possibly came through fracking chemicals rather than the way it would occur naturally.

JACKSON: That's right. These tracers and many others that we've developed and many other groups around the world have developed allow us to identify the source of contamination in the environment really well.

FITZGERALD: Why would we want to use this approach?

An aerial view of a wastewater treatment plant in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale. (Photo: Prof. Robert Jackson)

JACKSON: We want to be able to keep track of wastewater in the environment. We might want to see if a wastewater treatment facility is working properly. We might want to identify the source of a potential spill, if somebody thinks a spill has happened in their neighborhood or in their stream or river, has it actually happened and if it's happened what caused it? This allows us to go in and identify the sources of contamination in the environment and that's really important and very useful.

FITZGERALD: Professor Jackson, you called this a "forensic approach"...can you explain what you mean?

JACKSON: Well, at a crime scene, investigators will go in and and apply a forensic approach. They might gather DNA, they might gather blood types, they might gather hair, and they assemble a set of evidence to assess a probable cause, a probable weapon, even sometimes a probable person. So in science we can talk about forensics in the same way, we can gather and apply a suite of chemical analyses and then apply them to a particular situation and try to figure out what caused the problem.

FITZGERALD: You're fingerprinting fracking wastewater?

Robert Jackson is a Professor of Environmental Earth System Science at Stanford University and co-author on the study “New Tracers Identify Hydraulic Fracturing Fluids and Accidental Releases from Oil and Gas Operations” published in the Journal of Environmental Science & Technology. (Photo: Stanford University)

JACKSON: We are fingerprinting fracking wastewater. It's not the same scale of resolution as a DNA identification. It's not a one in 100 million or one and 1 billion chance. The tools are not that accurate, but they're pretty accurate.

FITZGERALD: In the end, what do you hope comes out of this research?

JACKSON: All of the research that I do in this area has a single purpose in mind. We want to improve things to make things better so we can provide some tools that companies and regulators can use to keep spills from happening, to track wastewater in the environment better and ultimately to make the entire process safer, then I think that's a good reason for doing the work. There's also a basic science component to this we're learning about what's found naturally deep underground so when I get a basic science project and a project with strong relevance today, I'm happy about that.

CURWOOD: Robert Jackson is a co-developer of the frackwater forensic fingerprint technique.

He teaches at Stanford University, and spoke with Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald.

Related links:

- Read the original study

- Duke’s press release on “New Tracers Can Identify Fracking Fluids in the Environment”

- Study co-author and Professor Robert Jackson’s Stanford University webpage

- Locate over 1.1 million active oil and gas wells, spills and wastewater injection on FracTracker

- Difficulty making frackwater clean-up profitable, our piece.

- ThinkProgress’ piece on tracking fracking waste

- Inappropriate disposal of solid, radioactive frackwaste contaminates water, our story.

[MUSIC: Kings of Convenience “Toxic Girl” from Quiet is the New Loud (Astralwerks 2001)]

Hyundai and Kia Fined for Misreporting MPG and Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Kia reported that the Soul could get 6 miles per gallon more than it actually was. Out of all the models involved, the Soul’s MPG was over-reported the most. (Photo: loubeat; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Some of South Korea’s most popular cars, like the Hyundai Accent and the Kia Soul, haven’t been getting their advertised gas mileage. And it turns out that Hyundai and its corporate sibling Kia misreported MPG ratings and greenhouse gas emissions to the EPA. Last year, the companies paid out nearly $400 million to settle a lawsuit with consumers who bought the affected vehicles. And now, the faulty reports will cost the firms another $350 million in fines, require testing upgrades and forfeited greenhouse gas credits. It’s part of a settlement with the EPA and the Justice Department for violating the Clean Air Act. The Union of Concerned Scientists gave the Hyundai and Kia fleets its top green rating of cars on the market this year, so we called up the UCS vehicle analyst Dave Cooke to learn more. Welcome to Living on Earth, Dave.

COOKE: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So what was the magnitude of Hyundai and Kia's over-reporting of their efficiency? How many cars are involved here?

On November 3rd, EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy (alongside US Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr.) announced Hyundai’s and Kia’s fines. McCarthy said, “Today’s settlement proves we don’t just talk the talk on climate action; we walk the walk. By enforcing our laws to protect our health, we also protect consumers and promote a vibrant economy.” (Photo: EPA; Flickr CC)

COOKE: It was more than half of their vehicles in the 2011 to 2013 model years, and so I think the last count was 1.2 million vehicles.

CURWOOD: And how far off the official ratings were they?

COOKE: They varied anywhere from one to six miles per gallon, depending on city or highway. It averaged somewhere in the neighborhood of two miles per gallon.

CURWOOD: I looked down the list of the various findings that needed to be adjusted, and what really caught my eye was the Kia Soul, made famous, by the way, by the Pope when he was in Korea, he rode in one - it's the tiny little car - and it looked like Kia had overstated the mileage by six miles per gallon. For a little car, that would be, I think, top of mind for somebody who is looking for vehicle, that instead of getting the 34 [miles per gallon] they were claiming on the highway it was getting more like 28.

The Hyundai Accent’s MPG rating was over reported by 2 MPG for city driving and 3 MPG on the highway. (Photo: Michael Gil; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

COOKE: Yes, I would agree. Six miles per gallon is a lot. The amount of fuel that that would correspond to annually is significant, and if you're in the compact segment obviously fuel economy is something that you're already very concerned with.

CURWOOD: And so the end of the day, what did that mean for customers?

COOKE: Well, it would mean that customers were unfortunately getting shortchanged with their vehicles. Last year the two companies settled with consumers to pay out hundred of dollars to each purchaser of their vehicle for fuel that they weren't saving.

CURWOOD: So how exactly did Hyundai and Kia - and I gather they're really the same company at the end of the day - how did they understate their emissions to the EPA?

COOKE: So they share a testing facility and the practices at that testing facility did not meet EPA standard, and that ranged from things like only submitting the best test results, as opposed to the average test results, or using the wrong tires on the vehicle and that helped improve the test fuel economy that would have been submitted to the EPA.

CURWOOD: Now, of the $350 million or so in penalties that's going to cost them, break that down for me. Who's getting that money?

New car labels like this one over-reported the efficiency of Hyundai and Kia cars’ MPG. (Photo: EPA; CC)

COOKE: Well, so also actually there's really only $100 million that's the penalty for breaking the rules. The common number of about $200 million that's thrown around, really what this is are greenhouse gas credits that they had submitted to EPA, and that EPA said, "Well these vehicles aren't actually as good as you're saying. So we are going to take those away." So that's not really a penalty, that's just accounting for the actual vehicle’s behavior in the real world. And the last of the $50 million and that $50 million is new auditing procedures at Hyundai, new testing facilities, retesting of vehicles out to 2017. So that is really just to make sure this doesn't happen again, and it was required by EPA. So really the $100 million is what it is to say “You guys broke the rule of the system needs to be fixed, and $50 million will fix it, and we're going to count your vehicles appropriately”.

CURWOOD: So Hyundai and Kia especially have build their brand on being super green. They make cars with great miles per gallon. So what does this episode, these fines, what's that going to do to their reputation with consumers, do you think?

Dave Cooke is a vehicle analyst for the Union of Concerned Scientists. (Photo: Courtesy of the Union of Concerned Scientists)

COOKE: It's hard to gauge. This first came to light in 2012. Hyundai Kia sales are doing fine. It certainly is problematic if I'm a consumer just thinking about fuel economy period. It does undermine your confidence in what the label says and I think this goes toward how consumers treat fuel economy labels generally. We found that Hyundai and Kia make the most efficient vehicles on average. At least did in 2013. That's why we named them the greenest automaker. The greatest tragedy is that if they had just appropriately represented their vehicle they wouldn't had to reimburse customers or the government and they could enjoy the fact that they've got the greenest fleet and are well on their way to meeting fuel economy and global warming emissions standards. There's a reason why Kia's announcement says they just want to move past it.

CURWOOD: Dave Cooke is a Vehicle Analyst for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much for taking the time today.

COOKE: Thanks for having me. I really appreciated it.

CURWOOD: Asked for comment, Kia says their priority is making things right for customers and Hyundai’s CEO writes that despite the problems his company “continues to lead the automotive industry in fuel efficiency.”

There are links to their statements at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- An EPA table showing all the affected vehicles and their revised MPG ratings

- The EPA’s press release about the settlement

- Kia’s website stating fuel efficiency inaccuracies

- Kia’s statement about the EPA settlement

- Hyundai’s press release about the settlement, including a statement from Hyundai USA’s president and CEO

- The EPA’s press release about the settlement

- Dave Cooke of the UCS

[MUSIC: Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis “Body and Soul” from Leapin’ on Lenox (Black & Blue 1794)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the joys of kelp...honestly! That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTWAY MUSIC: Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis “Body and Soul” from Leapin’ on Lenox (Black & Blue 1794)]

Restoring California’s Giant Kelp Forests

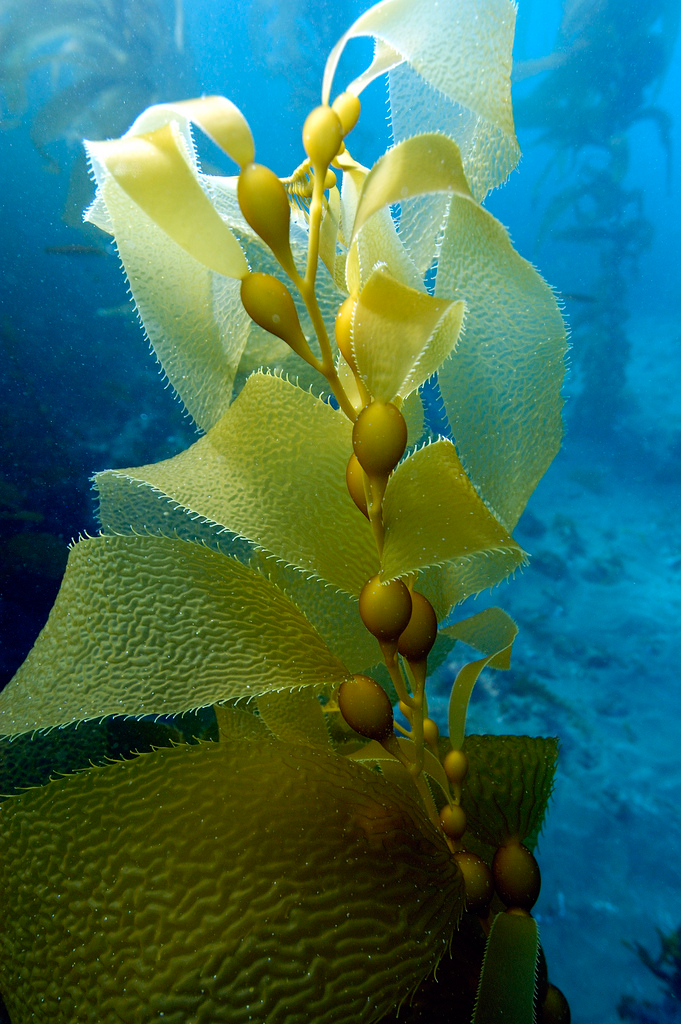

Kelp forests can grow up to 18 inches per day and prefer cold, nutrient-rich waters. (Photo: NOAA; CC government work)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. In late August this summer, huge mounds of the largest type of seaweed in our oceans, kelp, started piling up on Laguna Beach in Southern California. Tourists and would be sun-worshippers were not happy as the smelly thick brown ribbons took over the sand. Scientists estimated that hurricanes had ripped as much as 95 percent of the offshore kelp forest from the ocean floor nearby. But marine biologist Nancy Caruso says all that fly-ridden gunk on the beach is actually a sign of a healthy underwater ecosystem. Caruso is founder of the nonprofit Get Inspired!, which organizes volunteers and students to restore the kelp forests, and she joins us from Garden Grove, California. Welcome to Living on Earth.

CARUSO: Thank you very much I appreciate that.

CURWOOD: So explain to me exactly why all that kelp washing ashore is a sign, or could be a sign, of a thriving ecosystem?

CARUSO: Well, 12 years ago, myself and a group of students and volunteers all started a project to restore the kelp forests off of Orange County's coast. We've been kind of waiting as our restoration efforts appear to be successful. The real test comes when something like a hurricane or big swells coming out of the south show up and rip out all of our kelp, which is a natural occurrence, kind of like forest fires in the forest, where the forest is destroyed so to speak, but new life can start.

Kelp forests can be seen along much of the west coast of North America. Kelp are large brown algae that live in cool, relatively shallow waters close to the shore. They grow in dense groupings much like a forest on land. (Photo: NOAA’s National Ocean Service; CC BY 2.0)

So big holes have been created in the canopy of the forest and new life can grow from the bottom up, and so if we see this happen, which we're seeing right now, the kelp returns immediately after this event, then we know that our restoration efforts are successful, and after 30 years of our local ecosystem not having healthy kelp forests, we can rest assured that it's now restored and everything is back to normal again.

CURWOOD: For a moment let's talk about kelp itself. What does it look like and what is it taste like?

CARUSO: Well it looks like trees underwater, if you can imagine. Imagine being in a cathedral with stained glass windows and there's light dancing through the stained glass windows onto the floor, and that's what it looks like underwater in a kelp forest. These beautiful amber blades that the water...the sunlight, rather, dances through on the bottom of the ocean and creates beautiful light patterns. And as far as how it tastes, well, that's really up to the animal that's eating it, but for humans we actually eat it as well. Kelp contains a compound called alginate and it's used as an emulsifying and thickening agent so it binds things together and it makes things creamy and smooth. So if you ever had a diet salad dressing, for instance, if you take the fat out of it then it's not really creamy anymore, but you can add alginate back into it and that will give it the creamy texture. So we've eaten a lot in alginate in our lives, we're just not familiar with the fact that we're all intimately tied to giant kelp.

CURWOOD: How big are these giant kelp?

Get Inspired! Tour: Nancy Caruso and Pacifica High School students paddle out to evaluate the restored kelp forest. (Photo: courtesy of Nancy Caruso)

CARUSO: That's a good question. They're not called giant for nothing. So they can grow up to about 110 feet tall and they often, however, grow in water that's less than 30 feet deep. So the kelp forest grows up to the surface, then we have another 80 feet of kelp that just spreads out along the surface and creates what's called a canopy. And the canopy also provides cover for those fish that are swimming up and down our coast following the plankton, following the currents, and they can hide underneath that canopy from pelicans and other diving birds that are just waiting to eat them.

CURWOOD: So, Nancy, talk to me about how you actually restore kelp. I'm envisioning you strapping on a tank and mask and flippers and everything and going down there to plant little kelp seeds.

CARUSO: It was actually quite an effort because I had the help of 5,000 students from ages 11 to 18 as well as 250 skilled volunteer divers, and we planted this kelp in 15 different areas in Orange County. There's a spot down in Dana Point. It's the only kelp forest that was left in Orange County so we would collect the reproductive blades from those kelp plants, and I would take them into the classrooms for the students to clean them and we would actually stress them out overnight. We would leave them out of water in the refrigerator, kind covered with paper towels, and then the next morning we would put them back in the ice-cold seawater and the kelp blade would release millions of spores. They're microscopic. They're 400 times smaller than you can see, and we would get these spores to land on small little bathroom tiles, and then we would raise them in the classrooms in little nurseries that we built out of Home Depot parts and fittings, and the kids would raise them for about four months, just to the point where you can see them with your naked eye and then we would take these tiles out in the ocean.

A diver swims among giant kelp, which can grow as tall as 110 ft. (Photo: Ed Bierman, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CARUSO: After the kids learned all the ecology and biology and how the kelp disappeared, how to protect it, they became warriors for the kelp and then the volunteers would take it out into the ocean and using a rubber band really simply attach the tile to the reef. There would be thousands of kelp spores growing on each tile, and they would all outcompete each other and its root system, called the holdfast, would just grow off of the tile and attach itself to the reef, and the tile was nonleaded and unglazed so it could actually biodegrade - a rubber band is biodegradable - and there is kelp out there still that has started off from our tiles, so it's really gratifying to see that.

CURWOOD: Ah, you are the grandmother of how much kelp?

CARUSO: A whole lot!

CURWOOD: So what did the kelp forest look like before you started this restoration effort. Why did they disappear?

CARUSO: Well, it's actually a long process to collapse an ecosystem. We used to have furry little mammals living down here in Southern California called the southern sea otter, and they've been gone since the 1840s when the last otter was killed in southern California. Without the sea otter, things immediately started to go out of balance because the sea otter is kind of the top scavenger, I guess, in the oceans here and it keeps all of the animals that eat the kelp in place. So the otter disappeared and therefore the sea urchin populations got out of whack and we ended up with a lot of sea urchins on the reef and they basically mowed down the kelp forest.

So it started with the demise of the otter and then paving over the surfaces of southern California to where we don't have...or we have lots of runoff creating cloudier turbid waters off of our coast, and kelp likes sunlight. It is actually an algae so it produces food for itself through photosynthesis and it can't grow in deeper waters anymore. And the third and last straw for the demise of our kelp forests was actually the El Niño event of 1983, and that kind of like this year ripped out all of the kelp that was left in the area, however, there was so many other pressures on it, it never actually made it back.

Sea otters often tangle themselves up in kelp while they’re sleeping. Sea otters are crucial to a healthy kelp forest; they eat sea urchins and other invertebrates that feed on giant kelp. (Photo: Mike Baird; Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the responsibility that we as people have to restore kelp forests since we contributed to their decline.

CARUSO: Well, first and foremost, the number one thing that we can do is to stop runoff from going into the ocean. We don't get a lot of rain here, so every time it rains or whenever you're overwatering your lawn or washing your car, that water goes down our sidewalks, down our streets, washes over everything that's on the streets and sidewalks into the sewer system and directly into the ocean in most cases. And so trying to eliminate that runoff and the things that are on the streets and on the sidewalks that go with the water into the ocean is critically important and something that everybody can do on a daily basis.

CURWOOD: So, Nancy, I've got to tell you I spent time near Capetown, South Africa, where there's a huge kelp forest offshore, and that means that on the beach there are piles and piles of this big huge kelp and it's kind of smelly, it's got a lot of flies, people feel annoyed that they can't use that part of the beach. How do you cope with that? People come to southern California they want to, you know, go down to the beach and here you've got this stuff.

Among a few factors contributing to the decline in kelp is runoff from California’s agricultural sector. (Photo: Craig Jewell, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CARUSO: Well, kelp actually has a purpose when it washes up on the beach. It doesn't just end its life when it gets pulled off of the reef. Inside that massive wrangled tangled kelp, there're literally hundreds of animals living. So you'll see kids often going through the plant looking for starfish, crabs, lobsters and sea urchins and usually there's a chance actually for it to get washed back out again. And this is just like the process that I explained where we stressed the kelp out in the classrooms to get it to grow. We would take it out of the ocean and stress it out, keeping it moist and cool, which it does on the beaches, it's all wrapped up and stays moist and it shades itself, and then when the tide comes up again it can get washed back out into the cold water of the ocean and it'll reproduce. But also all those animals that get washed up on the beach inside the wrangled tangled kelp become a food source for shorebirds that live along our coast, and also there's a really special fish here in southern California called the Grunion, and it only spawns on our beaches not in the water but actually in the sand, and it only does it certain times during the year and it's a big event, everybody goes out to watch it, it's at night you know during certain phases of the moon, and the kelp can actually keep the sand moist on top of the eggs of these Grunion, so there's a whole ecosystem that occurs when the kelp gets washed up.

CURWOOD: What about the tourists? How does all the kelp affect the tourism?

CARUSO: Well, when you go to forest and there's leaves all over the ground, most people don't complain about that because they know that that's a natural process of leaves falling on the ground. So it's really about educating people what the kelp forest ecosystem is, and why it's important, and the whole entire cycle, not just out in the ocean and underwater, that slimy stuff that grabs my ankles when I swim over it, but it's also part of the beach, coastal ecosystem.

Nancy Caruso is a marine biologist and the founder of Get Inspired!, a program that performs kelp restoration in California. (Photo: courtesy of Nancy Caruso)

CURWOOD: And it has these tiny little crabs and periwinkles and stuff running around inside it.

CARUSO: Ummm hmmm. Exactly.

CURWOOD: So, you're so excited about kelp. When did you fall in love with kelp?

CARUSO: Well, I wanted to be a marine biologist since I was 10 years old in Virginia and ended up going to school in Florida and just by happenstance I made it out here to California and worked for a local public aquarium and that's where I really, I mean as a kid I watched Jacques Cousteau diving in the kelp forest in the Catalina Island in southern California and I often thought wow that's so cool like I wish I could go there, and when I finally ended up here I was just taken in by their majesty and their beauty.

CURWOOD: And shocked then that off of Orange County they were gone.

CARUSO: Yeah. The beautiful thing was that I was looking to do work within the community. I wanted to work with people and get people excited about doing conservation work, and then this opportunity to start up the kelp program became available to me and it was exactly what I wanted to do. I've kind of been able to become a messenger for the kelp and to give it a voice so to speak, so I'll keep an eye on it for as long as I can.

CURWOOD: Nancy Caruso is the Founder of Get Inspired! It's a nonprofit that gets Southern California residents involved in kelp forest restoration. Nancy, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

CARUSO: Thank you so very much.

Related links:

- The Get Inspired! Website and photo gallery

- Live Kelp Forest Cam at the Monterey Bay Aquarium

- What is a kelp forest?

Uprooting an Invasive Ribbon Grass on the Metolius River

Mike Crumrine adds dye to an herbicide mixture so that he can see where he applies it. Crumrine is applying herbicides to an invasive plant, ribbon grass that is choking Oregon's Metolius River. (Photo: Courtesy of Maret Pajutee)

CURWOOD: Now, from restoring a plant associated with water...to ripping one out! You’ve probably seen ribbon grass. It’s a pretty, leafy plant, and Better Homes and Gardens calls the variegated kind “a perfect plant for adding a dose of color anywhere you don't want to maintain; it's a fast-spreading variety perfect for covering slopes.” But “perfect for covering slopes” makes it something of an invasive nuisance in the Northwest, where it’s choking one of Oregon’s most pristine waterways. Courtney Flatt from the public media collaborative EarthFix has the story.

An island covered in ribbon grass. (Photo: Courtesy of Maret Pajutee)

FLATT: Looking at the banks of the Metolius River in central Oregon, nothing really seems wrong. But train your eye a little, and you start noticing large patches, even entire islands, covered in thin, green grass. Merit Pajutee’s a forest service ecologist.

PAJUTEE: Aldo Leopold said that living with an ecological consciousness is like living in a world of wounds.

FLATT: The wound on the Metolius River is ribbon grass. Its bunches of leaves have squeezed out native sedges and wildflowers. As the wildflowers disappeared, the number of pollinating insects dropped. Pajutee says rumor has it ribbon grass came to Oregon in the 50s, when someone planted the pretty grass in a flowerbed. Then, like most invasive plants, it kept growing.

The same island after treatment. Friends of the Metolius covered the island with a black tarp, hoping that less sunlight would kill the ribbon grass. They left the tarp on for three years. It killed the ribbon grass, but also killed other plants on the island. (Photo: Courtesy of Maret Pajutee)

PAJUTEE: And I think the reason it has done so well here is the character of the Metolius, and its spring-fed nature. It really found the perfect home, where it can spread.

FLATT: Ribbon grass is found throughout the Northwest. It’s relatively contained, but here on the Metolius it’s growing like crazy.

The Metolius is a wild and scenic river. It’s home to Oregon’s healthiest bull trout population and recovering salmon sockeye runs. One of the big concerns is that ribbon grass doesn’t provide a lot of cover for fish to hide in the winter. That’s why this year the Oregon legislature listed ribbon grass as an official noxious weed.

One organization trying to get rid of the ribbon grass is the Friends of the Metolius. For years the conservation group tried several tactics. They tried throwing black tarps over the grass. That didn’t work as well. Then they hand picked it. Pete Schay is with the Friends of the Metolius. He says handpicking the weeds was backbreaking labor.

SCHAY: It’s very heavy. It’s mostly water. It’s 99 percent water that you’re pulling - dragging around.

Crews filled a truck bed with ribbon grass they hand picked. (Photo: Courtesy of Maret Pajutee)

FLATT: Crews filled an entire pickup truck with weeds. They took the ribbon grass to a gravel pit and covered it with a tarp to kill it. A couple years later, the ribbon grass started growing back.

Now, they’re trying herbicides. Mike Crumrine is with the Oregon Department of Agriculture. He wades through the frigid waters.

CRUMRINE: Wiping the herbicide on with, in essence, a sponge. Rubbing the plant, every bit of the plant that you can get to that’s above water level, is the target goal.

FLATT: There’s a small window every fall when Crumrine can apply the herbicide.

Mike Crumrine applies herbicide to yellow iris, another invasive plant on the Metolius River. (Photo: Courtesy of Maret Pajutee)

REPORTER: So do you think you’ll ever be able to knock it all out?

CRUMRINE: Eventually, yes, I have some great hope. Looking at what we’re looking at right here, right now, I would estimate we’re looking at a 90 percent reduction.

FLATT: Water quality tests have shown the herbicides haven’t hurt fish or other species in the river. And the herbicides are working. There are finally a few places where native plants have started to come back.

I’m Courtney Flatt in Sisters, Oregon.

CURWOOD: Courtney reports for the public media collaborative Earthfix.

Related link:

Read more about ribbon grass and management of the species on EarthFix.

[MUSIC: Hall and Oats “I Can't Go for That (No Can Do)” from Private Eyes (RCA 1981)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of our team. Our show was engineered by James Curwood. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth