August 14, 2015

Air Date: August 14, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Rafting Down The Unbound Elwha

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

The National Park Service has finished removing the last dams that blocked the Elwha River for over a century in Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. The river now flows freely, open once more for salmon, otters, bears and rafters. Ashley Ahearn of EarthFix takes us for a ride down the river. (04:20)

Freeing The Arteries of The Planet

View the page for this story

The Elwha River restoration project is part of a broader movement to dismantle dams and let rivers run their natural course freely. But there is still a hydroelectric boom in developing countries and as International Rivers Director Jason Rainey tells host Steve Curwood, that’s putting many of the world’s major rivers in crisis. (07:30)

Alaskan River Riches: Fly fishing and Salmon Science

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

In the summer of 2014, Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald visited Southeast Alaska to report on the salmon economy and potential threats from new mining development over the border in British Columbia. In this report, he wades into a stream near Juneau for a lesson in casting and salmon science from a fly-fisherman with a conservation ethic. Emmett FitzGerald then joins host Steve Curwood to discuss how mining projects have moved forward since his visit and how Alaskan locals are responding. (13:55)

Encountering Black Bear

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

During the salmon run, writer Mark Seth Lender kayaked along a river in British Columbia. As he watched, a large black bear stepped out upon a nearby promontory, his eyes on the fish in the river. A mother and baby bear, also hungry for salmon, make way for the massive male. (03:00)

Alaskan River Riches: A River Town in Transition

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

Wrangell, Alaska is a small, isolated town at the mouth of the mighty Stikine River. As Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald reports, Wrangell was once a timber capital, but since the saw mills shut down in the ‘90s, the small town has reinvented itself as a tourist destination and a commercial fishing hub. Since both of these industries are dependent on the Stikine, some locals worry that mining development upriver could put the town’s economy at risk. (18:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

GUESTS: Mark Hieronymus, Jason Rainey

REPORTERS: Ashley Ahearn, Emmett Fitzgerald, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Examining the state of the world’s rivers – some experts say the mega-dams that generate mega power are destroying a vital resource.

RAINEY: The state of the world's rivers is in grave peril, and there is no international institution looking squarely at the question of: what are the tipping points, how much is enough, can we dam all our rivers for the sake of hydroelectricity and still have viable societies here on Earth?

CURWOOD: Dams and what happens when you tear them down – how wild rivers running free are arteries that feed the forest and in Alaska, help drive the economy thanks to wild salmon.

HIERONYMUS: If we give these guys fresh water and a good habitat to spawn in, these fish come back year after year after year and we can keep making money on them.

CURWOOD: But locals say plans for mines upstream in Canada could threaten the fish – That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

Rafting Down The Unbound Elwha

Now that the dams are gone, rafters are enjoying the changing Elwha River. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. We have a special show today that focuses on rivers, their value and their health. By 2015, more than a thousand dams had been torn down across the US, but the largest and, at $325 million, the costliest were two massive hydropower installations on the Elwha River. The Elwha runs through the Olympic National Park in Washington state, and after a century with dams, now flows freely all the way to the sea, and allows fish to swim upstream. Over the decades biologists, conservationists and Native Americans convinced Congress that the value of the dams for electricity was far less than the value of the Chinook salmon and steelhead trout that can now once more can swim deep into the forest to spawn. Soon after the dams came down, Ashley Ahearn, from the public media collaborative EarthFix, took to the water to experience the river unbound.

AHEARN: If you were going to, say, try to raft a river while holding a microphone, Morgan Colonel is the guy you want at the helm. He’s been a river guide for ten years.

Two dams blocked Elwha River for over 100 years. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

COLONEL: Alright, gang. Who wants to get the wettest?

[PARTICIPANTS VOLUNTEERING]

AHEARN: Colonel runs Olympic Raft and Kayak. He bought the company three years ago when he heard the Elwha dams were coming out and he’s had a front row seat to watch the recovery process ever since.

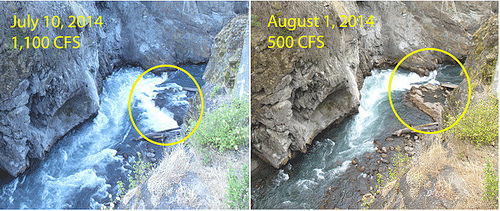

AHEARN: Colonel says the river’s changed a lot. New channels come and go as the Elwha twists back and forth across her bed, trying to find the fastest way to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

COLONEL: We’re kinda just figuring it out a little bit as we go. Brand new river to pioneer.

AHEARN: Salmon are starting to come back. This summer, state fisheries’ biologists counted more than 1,500 King salmon above the former site of the lower dam, and the otters, eagles and bears are catching on.

Un-damming of the Elwha River in Washington State (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

We head into a rougher patch of river as Colonel tells a story about the demise of one sockeye salmon at the hands of a mama otter and her pups, not too long ago.

The otters cornered the fish in a small eddy of the river but it escaped and took off downstream.

COLONEL: That otter was on it. I mean, from the word “go,” that mom headed downstream, but then five minutes later she comes back up holding the sockeye by the mouth. And that sockeye was about as big as her.

[RUSHING WATER]

AHEARN: Millions of tons of sediment have been released from above the dams, creating sandy beaches where there used to be rocky shoreline.

National Parks Services hopes to restore Elwha’s ecosystem. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

Rob Elofson joined Colonel to run the river today. He’s a member of the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe, which has been pushing for dam removal for decades. This is the first time he’s rafted the river since the dams came down. As the group paddles along, Elofson points out that the river is already looking more salmon friendly.

ELOFSON: The small sediment, sand and gravel, wasn’t here. It was just large rocks. And yeah, it’s completely different. It’s the way it’s supposed to be now.

[RUSHING WATER]

AHEARN: We round a bend and the water grows louder as it rushes into a tight curve, flashing with rolling white caps. This stretch of river is known as Ferngully, Colonel explains.

COLONEL: This is going to be our best rapid of the day. This is the fun…can be class three in higher water, probably class two plus right now.

[WATER CRASHES; PEOPLE SHRIEK]

AHEARN: We come out of Ferngully and the water slows, beautiful and clear beneath us. We’re above where the lower dam used to be, scanning the water for intrepid salmon, which have made it into this newly accessible territory to spawn. Nothing yet. We float quietly.

SCHMIDT: There’s one. I saw something shadowy.

Morgan Colonel, owner of Olympic Raft and

Kayak, on the Elwha (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

AHEARN: Kati Schmidt spots a sockeye salmon. She’s with the National Parks Conservation Association. The gleaming flash of red darts beneath us, headed upstream and into the Ferngully rapids.

SCHMIDT: Ah! Yup! Yay! Go fish go!!

AHEARN: Now that the dams are gone, that sockeye could be the mother, the grandmother, and someday the great-grandmother of countless generations of salmon to come—all free to colonize the Elwha, once again.

Since the removal of the first dam, the salmon have been coming back. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

[RAFTS TOUCH DOWN]

AHEARN: Whew, we made it.

[FEMALE LAUGHTER]

AHEARN: I’m Ashley Ahearn on the Elwha River.

CURWOOD: To see a video from Ashley’s trip down the Elwha, paddle over to our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Elwha River Restoration project from the National Parks Service.

- To measure the effects of the dam’s removal, biologists made baseline assessments of the ecosystem in 2011.

- Ashley Ahearn brought us into a hatchery in 2011 to explore another facet of this project.

- Destruction of the first dam filled the river with sediment—and the fish thrived. Hear more here.

Freeing The Arteries of The Planet

Fall along the Elwha River (Photo: NOAA, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, the long awaited dam removal on the Elwha River in Olympic National Park is part of a growing movement to restore rivers that have been hurt by hydropower development. Not only are large-scale dams tough on fish like salmon, they also disrupt other parts of the ecosystem, and can even contribute to climate change, river advocates say. Jason Rainey is the director of International Rivers and he joins us now to discuss the Elwha and the state of rivers around the world. Welcome to Living on Earth!

RAINEY: Thanks; it’s great to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: So how possible is it to restore a salmon run on a river like the Elwha?

RAINEY: Well the evidence has already come rushing back in. As soon as the dams were breached, the very next run had thousands, tens of thousands of salmon of various species moving into waters that they had not seen in 70 years, so quite remarkable and epic. You need a remnant run to recolonize, but they did so naturally and willingly in this case.

This dam on the Elwha was taken down as part of an effort to restore the natural flow of the river (Photo: Paul Cooper; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Interesting, because neither those fish or their grandparents or even their great-grandparents had ever made that run.

RAINEY: It's true, but there's something instinctual that it brought them up as far as they could go for generations and generations and generations, and once that barrier was removed, they were able to find better, more suitable spawning grounds.

CURWOOD: How common is what's happening on Elwha? Where else are dams coming down here in America?

RAINEY: Yeah, well in the United States there have been over 1,000 dams removed, a lot of them small dams on the East Coast and eastern seaboard. The Elwha dams are the largest of two that are being removed, but others have been removed in the Pacific Northwest as well and have supported a rebounding of salmon populations and another ecological benefits.

Now the Elwha River runs unimpeded. (Photo: claumoho; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What you think about the argument that we need hydropower because it's a renewable source of electricity?

RAINEY: Yeah well that's really the arena that I'm most engaged in these days at International Rivers. There's a hydropower boom happening globally that is unlike any other time before, and the pressure put on the world's rivers is great. My response to that question is that hydropower is really not a renewable resource in the most strict sense of the term—it's dirty energy in terms of what it does to polluting rivers and also polluting the climate with methane emissions, and it also fundamentally disrupts the ecological processes of rivers. And solar and wind are examples of true renewable resources that don't fundamentally alter sunlight or fundamentally change wind currents. Large hydrodams are a very different story.

CURWOOD: Talk to me more about methane and hydropower.

Thai villagers gather at the Thai Supreme Court to voice their opposition to a hydroelectric dam on the Mekong River. (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: Yeah, well, particularly in the tropics when you dam a river and flood an area, the vegetation in it begins to decompose in anoxic conditions with low oxygen. And the chemical reaction, to just put it very simply, is one that produces methane and methane can be emitted from those reservoirs. There are examples of reservoirs in the Amazon, for example, that are four, five, seven times more climate impact in their emissions than a coal power plant of similar megawatts. So these can be very major contributors to our carbon imbalance. It's estimated that dams and reservoirs account for four percent of anthropogenic carbon emissions globally, which is equivalent to all of the airline traffic globally.

CURWOOD: Now, for a number of years the World Bank said it wouldn't fund ginormous dam projects like we're seeing in developing countries. Why are they coming back on the drawing boards?

A boy holds a fish he caught on the Mekong River in Thailand. Critics say that the proposed Don Sahong Dam on the Mekong would be terrible for the fish population. (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: Yeah, that's a great question. They did back away because of a calculus and recognizing that the impacts and the voice of concern from throughout the world was too great and that they couldn't build these projects to meet their environmental and social standards, and that they're also generally not great returns on investment. What's changed is that there are many, many actors involved in hydropower building today: China, Brazil, India--a whole multitude of other development banks that are forming. And the World Bank and the leadership behind it—primarily the United States—is interested in not losing out, so it's part of a broader geopolitical game, really, that the World Bank is getting involved in hydropower development again.

CURWOOD: Now, Jason, your organization, International Rivers, recently released an online platform for looking at the health of the world's rivers. How does that work?

The Salween River in Burma is the largest undammed river in Southeast Asia, and these children want it to stay that way. (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: Yeah, State of the World's Rivers is a Google Earth based platform, and it's a spatial database, which means we've compiled a lot of information about dams. And we've focused on 50 major river basins of the world. And we've also looked at a whole range of indicators of river health if you will, factors such as water quality, biodiversity, the fragmentation of the river, and we've put this all on an interactive map-based platform that allows you to search through these 50 river basins. You can see how the various basins ranked according to one another on these various ecological health indicators.

CURWOOD: So overall, how are the world’s rivers doing?

The fast moving Baker River runs through Patagonia. “Sin Represas” means “Without Dams” in Spanish. (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: Well, the world's rivers are in grave crisis. We have over two-thirds of the world's rivers functionally impaired. They're not providing the range of services that they normally would, and we've known that for a long time. What this tool is intended to do is to start a conversation at the same level that is deserving of our climate crisis, which is that the state of the world's rivers is in grave peril, and there is no international institution, no panel of experts, looking squarely at the question of: what are the tipping points, how much is enough, can we dam all our rivers for the sake of hydroelectricity and still have viable societies here on Earth?

CURWOOD: What are we at risk of losing if the river crisis continues unabated, in your view?

Peruvian children watch the Ene River in front of their village in an area that would be flooded by Pakitzapango Dam. (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: Well, to begin with, we already know that we're losing more species in our rivers really than in any other ecosystem. The rate of species extinction is greatest in aquatic freshwater ecosystems, but beyond the animals that will never come back and the food web that they provide, we're really dealing with planetary cycles here. Rivers connect us to deltas and to coastal marine systems; they carve their way through the land and are the ribbon of life in dry and wet communities. So we really are on a grand experiment where we're seeing deltas shrinking and deltas are not just interesting ecological zones with a lot of birds. I mean, these are places where people live and are productive and can be used well, as in the case of the Mekong Delta, which provides rice for a great percentage of Southeast Asia.

Indigenous people protest the Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River in Brazil (Photo: International Rivers)

CURWOOD: Some use an analogy and call rivers the "arteries of our planet". If you were to go down that path, those arteries are getting clogged. Are we headed for some sort of metaphorical heart attack?

RAINEY: Yeah, it is a powerful metaphor. We are very much clogging the arteries of the planet, and in many cases, we're doing so under a very simple and false paradigm that says, well, you know the lungs of the planet are ailing—the climate is ailing; the atmosphere is out of balance—and the alternative right now is we'll just dam our way to some sustainable future.

Jason Rainey is the Executive Director of International Rivers (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINY: And it's really, it's an absurdity from an ecological perspective to think that that's possible and that is exactly what we're confronted in nation after nation and region after region throughout Latin America, Africa and Asia, regions that have very legitimate needs for energy access and development, but are doing so by pushing a mega-dam energy agenda. And it's - it's just a dangerous course for the planet.

CURWOOD: Jason Rainey is Executive Director of International Rivers. It's been my pleasure to speak with you.

RAINEY: Thanks so much, Steve.

Related links:

- International Rivers

- The State of the World’s Resources Map

[MUSIC: Jaco Pastorious “Continuum” from Jaco (Warner Bros 1976)]

CURWOOD: Coming up -- heading north to Alaska – in search of fish in its pristine rivers.

Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Baubles Bangles and Beads), Christian McBride (featuring Roy Hargrove), Conversations with Christian, Mack Avenue, 2011]

Alaskan River Riches: Fly fishing and Salmon Science

Mark Hieronymus fishes in a stream just outside of Juneau. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: It's an encore edition of Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Summer in Southeast Alaska is salmon season. As the days grow long, the iconic fish begin to run up rivers and streams, and the fishing economy jumps to life. Juneau isn’t the biggest fishing town in the region, but salmon are everywhere: on every restaurant menu, on T-shirts in gift shops. And in the harbor, hundreds of fishing boats constantly come and go. Just a few miles outside of the city, small commercial fishing boats cruise around the mouth of the great Taku River, netting the salmon as they head upstream. Juneau is also a popular jumping-off point for fly-fishing trips, and sport fishing is an important source of income. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald spent some time in Juneau in the summer of 2014, reporting on the fish, their importance to the people who live there – and potential threats to the salmon that drive the local economy. And a fly-fisherman with a conservation ethic gave Emmett a lesson in casting and salmon science.

FITZGERALD: It’s a blue summer day, about as warm as it gets in Southeast Alaska. Fly-fishing guide Mark Hieronymus has the morning off, but he’s more than happy to spend it at one of his favorite fishing holes—although he’s not about to let me give away the precise spot on national radio.

HIERONYMUS: You could say that we’re at a small stream very close to the mouth of Taku River in Taku inlet.

[SOUND OF TRAMPING ALONG BANKS]

FITZGERALD: In chest high waders, we tramp along the pebbled banks. Where the stream narrows, Mark wades in and we slosh across to the other side.

[SOUND OF SLOSHING WATER]

FITZGERALD: The rushing water squeezes the waders tight and cold against my legs, and I have to lean into the current to avoid toppling over.

[SOUND OF SLOSHING WATER CONTINUES]

FITZGERALD: On the other shore Mark sets up shop. He puts his pole together, ties on a feathery orange fly, and starts showing me how it’s done.

HIERONYMUS: You’re going to go like this with this rod, you’re gonna cast it back out there and you want to cast this kind of gentle, so I’ll show you this cast called a roll cast.

FITZGERALD: OK.

HIERONYMUS: If it ever tightens up, that’s a fish.

FITZGERALD: There’s so many fish in this stream that even I manage to get a few bites, but Mark’s the real master here. As the line dances back and forth above his head, he tells me about the different salmon in Southeast Alaska.

HIERONYMUS: The largest of those in terms of numbers are pink salmon. The run sizes fluctuate but this year, to give you an idea, this is going to be a poor run of pink salmon this year and they’re projecting a harvest of around 22 million with a total escapement of somewhere over 30 million.

FITZGERALD: There’s five salmon species in all. As well as the pink there’s Chum, Coho, Sockeye…

Hiking in, fishing pole in hand. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

HIERONYMUS: And then we get King Salmon too, that run in here. Those are the commercially caught fish and then we have also steelhead, which is the anadromous form, the ocean going form, of rainbow trout. That’s sort of the prized sport fish, that’s the crown jewel of most sport catches and here in Southeast Alaska we have officially about 330 streams with steelhead in them. But if you talk to folks that have fished for them for a long time they’ll tell you that that number is closer to 450 streams of steelhead in ’em.

FITZGERALD: This one?

HIERONYMUS: This one does have Steelhead but you don’t have to print that.

FITZGERALD: Mark lands his fly a few feet from the opposite bank, just above a cluster of dark shadows hanging in the water. They look like rocks to me, but Mark says they’re pink salmon, or as he calls them, humpies after the characteristic hump on back of the male. These humpies are in their final days of life, waiting for more salmon to join them upstream. When they get a quorum, they’ll spawn and die.

HIERONYMUS: These humpies have a two-year life cycle. So these fish here when they spawn, they’ll die and they enrich the stream here. And the young swim out to sea next year, next spring. Those fish will return in 2016 in the same numbers, sometimes even more.

FITZGERALD: It doesn’t take long for Mark’s fly to get some action.

HIERONYMUS: Well, this is a pink salmon. Looks like a female, and it’s a little one -- grabbed it.

[SOUNDS OF FLOPPING AND SPLASHING]

FITZGERALD: There you go.

HIERONYMUS: Yeah. It’s got a little nip on the outside of him there. There’s seals that sit out off of this--the river mouth here--and the seals’ll try to grab the fish.

FITZGERALD: Wow, look at that thing. So you think that wound there is a seal?

HIERONYMUS: Yeah that’s most likely a seal; it’s pretty fresh.

FITZGERALD: Is that going to be life-threatening to that fish?

HIERONYMUS: Well, the thing about it is this fish is on its spawning run, so its days are numbered right now, and so that wound might get infected, but that’s not going to be the cause of it dying. The cause of it dying is going to be—it’s on its spawning run; it was gonna die anyway.

A tributary in the Taku River Valley, a major salmon river that flows into the sea outside of Juneau. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: The salmon life cycle is a well-documented natural wonder. Somehow, each fish manages to find its way back from the open ocean to a little stream like this one, where it was born. Scientists think they use the earth’s magnetic field and their sense of smell to help them get back home, but it’s still a bit of a mystery.

This summer, though, the salmon cycle was disrupted on one of the biggest sockeye rivers in North America. On August 12th, a dam holding back waste water from the Mt. Polley copper and gold mine in British Columbia burst, sending over 6 billion gallons of polluted water and mine waste into the Fraser River, just as the sockeye had begun to swim upstream. Mark says that as he watched the horrific images on the news, all he could think about was the salmon.

HIERONYMUS: Once they enter fresh water on their spawning run, their time is limited. And so they have to find clean gravel and have clean water to spawn in. That’s the whole reason these fish come back. So if there’s no place for them to do it or if the habitat is compromised, then the results are, potentially, you’re missing an entire year class of fish.

FITZGERALD: Canadian officials say the Fraser River Sockeye have weathered that spill fairly well, but it’s way too early to know what the long-term impact on the population will be. The wastewater was filled with heavy metals that could linger in the rivers and lakes for years to come, and that’s bad news for the salmon.

HIERONYMUS: What people don’t think about are the effects of some of these harmful toxins to phytoplankton or in-stream invertebrates. And if you lose that food base, then you’re going to lose the fish. It’s not an “if.” If there’s nothing there for them to live on, then you lose the fish. You’re basically ripping out the bottom of the food chain and the fish follow.

FITZGERALD: Mark hopes that the Mount Polley disaster is a wake-up call about the dangers of mining in sensitive watersheds. British Columbia is in the middle of a mining boom, and several BC mines are planned along rivers that flow right into Southeast Alaska—rivers like the Unuk, the Stikine, and the Taku, near where we are right now. Mark says that if anyone doesn’t understand why these projects are a bad idea, just look at Mount Polley.

HIERONYMUS: The potential for something like that to happen, as we’ve seen, has now gone up greatly, because it has happened. And so to have it happen in a place that produces, place like, say, the Taku valley, or the Stikine valley, or the Unuk valley, that produces a substantial amount of Southeast Alaska’s fish, frankly it’s fairly horrifying.

FITZGERALD: As he talks, Mark is constantly casting, his arm rocking back and forth with a practiced finesse. He lays the line down on the water and lets the fly drift through the salmon shadows. If they don’t bite in five seconds, he yanks it out and starts again. For Mark, protecting fish is a personal economic issue. He’s had a lot of different jobs since moving to Juneau 25 years ago—seafood processor, fly designer, and today, as well as being a fly-fishing guide, he’s the Sportfish Outreach Coordinator for Trout Unlimited Alaska.

Mark is a fly-fishing guide based in Juneau. He takes tourists out on day-trips to streams like this one. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

HIERONYMUS: People, when they find out I work for Trout Unlimited, they say, is that some kind of environmentalist organization? I say, no, we’re conservationists, there’s a big difference. I want to conserve it, so I can keep killing it and keep making money off of it. But they have to be around for me to do that.

FITZGERALD: Before long, Mark’s got another fish on the line.

[SOUNDS OF SPLASHING WATER]

FITZGERALD: He pulls the salmon out of the water. It’s another female, he says.

HIERONYMUS: The thing that people don’t really realize is that, if we give these guys fresh water – clean water – and a good habitat to spawn in, the management is such that these fish come back year after year after year and we can keep making money on ’em.

FITZGERALD: Mark pulls the hook out of the lip and slides the fish back in the water. It lingers for a moment then swims off. In only a few weeks, he says, she’ll lay her eggs and die. But if the water stays clean and the habitat healthy, he’ll be back on this bank in two years, trying to catch her children.

For Living on Earth, this is Emmett FitzGerald in Juneau, Alaska.

CURWOOD: So, Emmett, it’s been – what – a year since you visited Alaska, and I want to hear how things have moved on since then. Mark Hieronymus talked about this horrendous spill at the Mt. Polley mine. How’s that river doing and how are the salmon, a year after that?

FITZGERALD: Well, it’s a little too early to tell about this summer’s run. In fact, scientists are actually more worried right now about the weather than the Mt. Polley situation. They’ve had a really hot summer – you’ve heard about these wildfires in the Pacific Northwest – and the water’s really, and the level is really low, and that's tough on salmon. But in terms of the spill itself, it’s still unclear what the overall impact will be. It could take years for those toxins to work their way up the food chain and actually start affecting the fish. But salmon advocates in Southeast are worried, because they’re actually talking about reopening the mine.

CURWOOD: Really?

FITZGERALD: Yeah, the mining company got approval to begin limited operations. They still need more permits before they get back to where they were before. But yeah, people are pretty concerned. There was an independent report that looked into the situation at Mt. Polley to determine what went wrong and make some recommendations. And many of the activists that I talked to are saying that the recommendations they made – things like not storing mining waste in watery ponds, which flood out into rivers – those sorts of recommendations aren’t being followed as the mine reopens.

CURWOOD: And, Emmett, it’s not just the Mt. Polley mine; in the piece the fisherman Mark Hieronymus mentioned a mining boom in British Columbia, huh?

King Salmon gather together to spawn. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

FITZGERALD: Yeah, British Columbia is in the process of developing a series of metal mines along the border with Southeast Alaska. And most of them are in really important salmon watersheds – rivers that flow from British Columbia over the border into Southeast Alaska. They’re mines like Shaft Creek, Galore Creek, Tulsequah Chief, Red Chris, and then the one that’s gotten the most media attention is the KSM mine – Kersel Fretz Mitchell. And that’s a massive copper and gold mine that’s being developed in the headwaters of the Unuk River, which is a big transboundary river, they call it, which flows from British Columbia into Southeast Alaska and empties out right next to Juneau, the state capital. KSM has gotten the go-ahead from BC, but it’s spinning its wheels now, more along financial lines, for financing reasons. It’s a huge, huge project – they need billions of dollars of investment, and they just don’t have that yet.

CURWOOD: So how are the people in Alaska responding to all this mining development?

FITZGERALD: Well, commercial fishermen and native Alaskans, in particular, in the area have really been up in arms about KSM and all of these other mines. They’re saying there just isn’t a strict enough environmental review in British Columbia. The waste from mining operations is called tailings, and when it comes to the surface, it can interact with the air and become acidic, and very toxic to fish. And what people in Southeast Alaska are saying is, you know, we don’t get any of the jobs, or any of the benefits from these projects, but we incur all the risk, when those tailings have the potential to wash into the rivers and flow downstream and hurt their fish populations. So they’re looking at Mt. Polley and saying, this is a perfect example of what can go wrong with these kinds of massive mining projects.

CURWOOD: So, how is the Alaskan state government and the federal government responding to these concerns?

FITZGERALD: Well, a lot of activists that I spoke with aren’t all that happy with the state response. I spoke with Kyle Mosele from the Alaska Department of Natural Resources, and he says you know, he trusts British Columbia’s regulatory processes on these things – which is not a view that’s shared by some of the fishermen I spoke with. The environmental activists have tried to get past the state and go to the federal level. They’re calling on the State Department to invoke the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty, which has been used in the past to regulate rivers that flow across national borders. But the State Department, for now at least, seems pretty reluctant to get involved. They’ve said it's more of a local issue, in their opinion. BC minister of mines Bill Bennett is coming to Alaska in late August, and he’s going to meet with state government officials about this. And activists really want them to come to a strict agreement that will deal with what happens when a spill occurs and has downstream impacts on Alaska.

CURWOOD: So have any of these mines actually opened?

FITZGERALD: Well, the one that’s furthest along is Red Chris. That’s a copper and gold mine owned by Imperial Metals, the same owner as Mt. Polley. And it’s being developed in the headwaters of the Stikine River, which is another one of these major transboundary rivers that flows into Southeast Alaska near the little town of Wrangell. And you’re going to here more about Wrangell and the Stikine later in the show. But it’s a big salmon river, not a lot of development on it now. And people in the town are very concerned about this project. The local government wrote a letter in support of the Federal Government getting involved, through the Boundary Waters Treaty. And the Native Tlingit people are also very concerned, and are also calling on the federal government to get involved. But across the border, the Tahltan First Nation in British Columbia actually reached an agreement with the owner Imperial Metals. And they’re going to be getting some of the profits and some jobs out of the deal, and partially as a result, that mine has opened up. And it’s ramping up its operations as we speak.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald. Thanks so much, Emmett!

FITZGERALD: Thank you.

Related links:

- Read more about fly-fisherman and conservationist Mark Hieronymus

- Watch a video of the Mount Polley spill

[MUSIC: Blues En Fa, Arturo Sandoval, My Passion for the Piano, Columbia 2002]

Encountering Black Bear

During the salmon run, writer Mark Seth Lender kayaked to the mouth of a river in British Columbia. As he watched, a female black bear and her cub stepped out upon a nearby promontory, her eyes on the fish in the river. Later a massive male appeared, and they made way for him. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Well, once the salmon start running up the rivers of the west, it’s not only fishermen that look to a bountiful harvest – bears do too. But as Mark Seth Lender observed at British Columbia’s McKenzie River, a plentiful supply of salmon doesn’t make bears less watchful and cautious.

Black Bear at the McKenzie River, Broughton Archipelago

© 2015 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

Here is the daybed he made; the reeds flat as a sheet for the space of 10 feet. He’s just the right size to lie in it. That head, the shoulders it slouches into, front legs like two angular granite monuments, black hair thick as a shag rug and the edges silver, shimmering. He came up the beach at a shambling pace, over mussels and hard white barnacles clinging to the rocks like glass-embedded crenellations. He crossed the estuary at the shallows, downstream from where the river pours out of the heavy woods. Then up the bank. And paused. Looking left, looking right, and along the grassy knoll and down to the promontory where he now stands. Staring. At me. Eyebrows raised in a kind of question mark. Eyes open wider than they should be. Chin lifted, a little. An expression you might take for surprise. It isn’t.

A large black bear approaches the river and pays an uncomfortable amount of attention on writer Mark Seth Lender. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Yesterday another smaller bear black as a lump of coal, was fishing for salmon, right there; paw raised, leaning way out, all his attention on the river and the motion below – until he realized he was not alone. Hungry as he may have been, he ran. Suddenly. That’s what they do. Small Bear from Big Bear. All bears from us.

Big Bear? He missed that part in Bear School…

And I am glad of the hundred meters of glass-green water between us. He kneads his claws in the sand, and never takes his eyes off me.

An salmon spawns in BC's Mackenzie River, then flops on the gravel streambed--her final resting place. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

On the rocks at my right hand, a salmon writhes. We tried to launch her again, upstream to meet her Fate. She did not have it in her. When Big Bear sees her there Fate will come to her.

Better her…

In the morning we kayak around the corner and along the promontory one last time. It rained last night and the river pushes against the flooding tide with a roar. There are tracks all over the flats. Momma Bear, her prints no bigger than the ones I might make walking on my hands. Baby Bear; here’s where he came to a stop feet planted side by side, and Momma Bear right behind him. And there, just ahead, that’s where Big Bear went. And Momma and Baby again, their paws bunched together in a clump which means they turned and left here at a run.

All these traces will wash out on the dark of the new moon tide. And of the stranded salmon? Not so much as a single, iridescent, scale.

Where momma and baby bear stopped, turned and ran. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Related links:

- Writer Mark Seth Lender

- Nimmo Bay Wilderness Resort in the Broughton Archipelago

- More on the Broughton Archipelago Provincial Park

[MUSIC: Both Sides Now, Herbie Hancock, River, Verve, 2007]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A portrait of a special community in Alaska – and its prospects if Canadian mines go forward. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth – stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provide building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Pent Up House, Chet Baker, Chet is Back, RCA Bluebird, 1990]

Alaskan River Riches: A River Town in Transition

The Stikine River (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: It's a recycled edition of Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Southeast Alaska is a patchwork of tiny coastal towns, connected only by a network of ferryboats. The ferries run 24/7 all year long, carrying backpackers, businesspeople, and high school sports teams from one town to the next. If you take the afternoon ferry heading south from Juneau, at about 5 in the morning you’ll get to Wrangell. This sleepy little fishing town is located on Wrangell Island, a few miles from the mouth of the Stikine River, and is home to just over 2,000 people. Every summer locals head out of town and travel up the Stikine to fish and hunt, and the river is the center of an emerging tourist economy. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald headed to Wrangell for this report.

Passengers sleep on the ferry that runs between Juneau and Wrangell. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Nancy Barlow, a kind-faced woman of about sixty five, first came to the little town of Wrangell on a ferryboat 16 years ago.

BARLOW: I came up on the ferry, spent a month running around the interior, and then spent another month coming back down stopping at all islands along the Inside Passage and I stopped here.

FITZGERALD: Wrangell has two harbors, 4 bars, 1 hotel (the Stikine Inn), and the only 9-hole golf course in Southeast Alaska. Nancy says it didn’t take her long to fall in love with the place.

BARLOW: The people are friendly, the dogs are friendly, [LAUGHS] and it’s just a beautiful little town.

FITZGERALD: Now Nancy’s the manager of a youth hostel based in the first Presbyterian Church. Life in Wrangell is isolated, but Nancy says that she meets people from all over the world, and has neighbors of all species.

BARLOW: When you go for a drive you have to be careful; there might be a deer crossing the road, you might see a moose, oh there’s a bear over at the airport. It’s the natural environment that people down south don’t ever get to see.

FITZGERALD: One of the most striking aspects of that environment is the Stikine, a glacier-fed river that springs up in the mountains of British Columbia and empties into the sea in a muddy delta a few miles outside of Wrangell.

HAASATH: I can recall first time I went up the river I was eight years old.

FITZGERALD: Einar Haasath is an elder in Wrangell’s Tlingit community, one of the biggest tribes in Southeast Alaska. He says when it comes to the Stikine, his grandmother taught him everything he knows.

HAASATH: I can remember my grandmother, she came to Wrangell in 1927 and the following year she met up with a couple of old friends and they took her up the river and they went after subsistence fish, and she continued to do for several years and kind of instilled in me that that’s a good practice, at least you can put food on the table.

FITZGERALD: So he follows his grandmother’s advice.

The commercial fishing dock in Wrangell (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

HAASATH: Each year I go up there and get sockeye and put that up for the winter, and do my moose hunting and I’m not successful all the time but nobody is. And then as far as berry picking and all that I gather high bush cranberry every year and bring it down. You know, it’s pretty productive.

FITZGERALD: When Einar was a kid he would take a riverboat 60 miles upstream, across the Canadian border and deep into British Columbia to a little river town called Telegraph Creek.

HAASATH: And I kind of thought, yeah this is the place to be because there was a hustle and a bustle up there, and that was the first time I ever run into a horse. Saw a horse for the first time.

FITZGERALD: In Telegraph, Einar met people from the Tahltan First Nation, a Canadian Tribe from the Upper Stikine. The Tlingits and the Tahltan shared the river and its resources for centuries. The coastal Tlingit traded what they got from the ocean, shell tools and oil from a fish called the Eulachon, to the interior Tahltan for caribou hides, moose, and snowshoes. Marge Bird, a Tlingit elder in Wrangell today, remembers the trade from when she was a little girl.

Fishing boat crew members load up their vessel. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

BIRD: The people from Telegraph would come down there and bring their smoked moose hides and their dried fish because they can dry it up there, and trade, trade our halibut and different things we could get here with what they got up there.

FITZGERALD: But Native Alaskan’s weren’t the only ones interested in the river’s bounty. Russians arrived in the late 18th century in search of fur. And they found willing trading partners in the Tlingit, who often acted as middlemen, selling them otter and beaver pelts they got from the Tahltan at a higher price. Then the Hudson Bay Company got involved in the fur trade, and by 1850 the otter and beaver populations had collapsed. But in the 1860s prospectors discovered gold, and the Cassiar and Klondike gold rushes brought waves of settlers to the Stikine and its tributary the Iskut. By the turn of the century they had established the town of Wrangell at an old Russian fort a few miles from the river. The mineral resources in the area are vast, and Angie Eldred of the Southeast Alaska Watershed Council says that gold mining continued in the 20th century.

ELDRED: In the 1980s and up to I think the late 90s there were two mines on the Iskut where they were mining gold, it was a smaller scale operation, but they were shipping a lot of the ore out on hovercrafts and by air plane and so it went through Wrangell and it provided jobs.

FITZGERALD: But larger mines could be on the way. In 2014, British Columbia completed a 750 million dollar powerline to bring cheap electricity to the Upper Stikine. With that in place, three new Canadian copper and gold mines are now in development. Angie says that people in Wrangell have supported mining in the past, but these mines are a different story.

ELDRED: Wrangell doesn’t stand to gain anything. There’s no jobs coming to Wrangell, we just stand to – you know - take on all of the risk if something were to go wrong.

This Forest Service hut is one of the only buildings for miles in the Stikine-Leconte Wilderness area. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: The new mines are Shaft Creek, Galore Creek and Red Chris.

ELDRED: And all of those mines are on tributaries of the Stikine River. So you know it’s all part of that watershed and if anything were to go wrong or there were to be a water quality impact it’s going to wash downstream and it’s going to impact all of our resources that are downstream and on this side of the border.

FITZGERALD: Angie’s not the only one concerned about the impacts of mining. Brenda Schwartz-Yeager has lived in Wrangell her whole life, and takes tourists on boat trips up the river to see the wild glacial landscape of the Lower Stikine. I met her on board her jet boat in the rain.

SCHWARTZ-YAEGER: Wrangell wouldn’t be here today or earlier if it wasn’t for the bounty of the river. The whole reason this community is here is because of the river. I mean the natives came down the river and settled this area because it was so rich and bountiful. And the reason it’s so rich and bountiful is all these nutrients in the river and all the fish.

FITZGERALD: Brenda’s family has lived in Wrangell for over a century, and they’ve always made their living from the river. Her grandmother was a trapper, and her father was a scientist who studied the Stikine.

SCHWARTZ-YAEGER: My dad was a fisheries biologist for this area, game warden, and probably one of the first Caucasian men to walk most all of the tributaries of the Stikine, looking at its massive salmon runs.

FITZGERALD: The river runs through the 450,000-acre Stikine-Leconte Wilderness—a swath of rugged mountains with old growth spruce and hemlock crawling up from the river valleys. It’s crowded with moose, lynx, grizzly bear, and one of the largest seasonal gatherings of bald eagles in North America.

SCHWARTZ-YAEGER: Wildernesses don’t really seem to work very well when they’re very small little postage stamps. In order for the ecosystem to really function, you need this vastness and the Stikine, the significance is it’s one of these vast places left in the world that’s fairly set aside and a little bit untrampled on.

FITZGERALD: Brenda says the few hardy tourists who travel the river with her won’t forget that vastness.

SCHWARTZ-YAEGER: I like to make them kind of take a breath and realize in a little bit of a way compared to all that vastness how kind of insignificant we are. Cause we’re kind of used to controlling everything all the time, changing the temperature, changing the lighting, and I think it’s a good experience for us humans to every now and then be out of control a little bit.

Shakes Lake, filled with icebergs that calved off of Shakes Glacier (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Brenda’s all booked up this weekend, so I’m heading up the river with one of her friends, Mark Galla, burly, grey bearded, and wearing a red plaid coat like a good Alaska lumberjack. Mark runs one of the only other jet boat tours up the Stikine.

GALLA: 30 minutes time out of Wrangell and you’re kind of right in the middle of a wilderness where you have great fishing, hunting, glaciers, you know, it’s kind of all here and right out our back yard.

FITZGERALD: Right now his backyard is surprisingly undeveloped, but that could soon change. In addition to mines, Mark says that hydroelectric power has long been considered on the Stikine and the Iskut. Throughout North America large rivers have been dammed for hydropower, and Mark says there aren’t many wild rivers left. But the Stikine is one of the wildest.

GALLA: Fastest free-flowing navigable river in North America. Meaning there’s no dams or obstructions along the course of its length to impede any type of flow.

FITZGERALD: It may be the fastest wild river in North America, but down here near the ocean, the Stikine runs slow and brown. It’s laden with silt dragged down by over fifty glaciers that feed into the river valley. Mark starts up the boat and warns us it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

[ENGINE MOTOR STARTS; DRIVING SOUNDS CONTINUE]

GALLA: The deep water tends to cut from outside corner to outside corners. There are a few places where those corners aren’t what they should be, which we’ve learned from the school of hard knocks. So I’m not just zigzagging and doing it all for effect, it actually has purpose. And there’s a lot of times where it looks like there’s a lot of water, and there’s really none.

FITZGERALD: From the boat the river looks narrow, but Mark says this is just one channel in a tangle of braided waterways. As warned, he jerks the jet boat all over the channel, dodging rocks and shallow spots. The muddy banks are covered with gnarled driftwood and entire trees, ripped out and dragged down here by the rapids upstream. Around a bend an island appears in our way and Mark pulls the boat to a stop.

GALLA: So this is one of the major places where the guys set their subsistence nets. It’s right around this island. There’s usually one or two of three nets dangling off this.

FITZGERALD: Mark says he come up here to hunt. Deer, bear, moose, even mountain goats.

Tlingit Elder Marge Byrd (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

GALLA: Most all the mountains that you see surrounding the whole river corridor have mountain goats in them.

FITZGERALD: He points out a cluster of them, just tiny white dots against the high green hillside. As a light rain starts to fall, Mark steers the boat down a small side stream. Around a bend our view suddenly opens up and we’re in a lake packed full of giant blue icebergs. Mark says the ice calves off of Shakes Glacier at the other side of the lake, then floats down here.

[SOUNDS OF ICEBERG LAKE]

GALLA: Everything gravitates to the outlet, so all of the ice that comes off of the glacier ultimately is going to end up at this end.

FITZGERALD: Mark wants to show off the glacier, so he tries to steer the boat across Shakes Lake through a maze of icebergs.

GALLA: Sometimes you can work through the middle, but usually one side or the other you can kind of eke your way through and every time I come here I try it.

FITZGERALD: But it doesn’t work today. The hull of our boat grinds against an iceberg, and Mark has to back out the way we came in. On the way back to town we stop at a Forest Service hut to eat lunch. It’s a tiny A-frame, the only building in a sea of trees.

GALLA: My family moved up here because of logging, timber, in 1967. So I was 7 years old when they moved up here, so I just was in between jobs at 7 [LAUGHTER] and I thought I’d go with them.

FITZGERALD: For most of the 20th century timber was the big industry in Southeast, Alaska. Timber companies signed 50-year contracts with the state to log the spruce, hemlock, and cedar of the Tongass National Forest. At the peak there were three sawmills in Wrangell, the largest employers in town. But despite large government subsidies the timber industry in Wrangell eventually went bust. Mark says it just wasn’t economical to harvest trees in such a remote location.

GALLA: You have to access the beach somewhere. Then you have to start building roads then you have to move all your equipment in to do all that, and it’s just all those expenses, tugs and barges and moving equipment, you know lower 48 or Canada, they start their trucks up and go do what they do.

FITZGERALD: It’s a familiar American story. Just like old factory towns in the rustbelt, when the sawmills in Wrangell closed their doors, people left town.

GALLA: We used to be 3000 plus people, now we’re more like 2200 or so, so we took a pretty big hit on population really, by nearly a third, when that timber stuff went away, but we seem to have adjusted. People just diversify in different directions and do different things, for us it largely was tourism.

FITZGERALD: But there aren’t many tourists. Wrangell isn’t on Southeast Alaska’s cruise ship circuit. There aren’t any gift shops and only a few places to eat. Still a small contingent of outdoorsy visitors is giving the town a new post-timber identity, and the main reason they come is the river.

Tis Peterman and Einar Haasath (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

GALLA: In fact without the river I really doubt that Wrangell would be Wrangell. You know that’s kind of the big draw for us and I think kind of what put us on the map.

FITZGERALD: Tourism may be on the rise, but the biggest industry in Wrangell is fishing. There are two seafood processing plants with hundreds of employees, and tonight the harbor is packed with boats, back in town to sell their catch and refuel.

[SOUNDS OF THE STIKINE INN BAR]

One of those boats belongs Brian Meritt, an elementary school teacher and commercial fisherman. He meets me at the bar in the Stikine Inn, wearing a faded baseball cap and a NYPD sweatshirt. Brian says he’s been fishing since he was in elementary school.

MERITT: Started fishing with Dad, just kind of escalated from there. Bought my own boat when I was 19, put my way through college with it, that sort of thing, and it’s just I’ve always had a boat, then I got a teaching job.

FITZGERALD: A lot of Brian’s students come from fishing families, and he tries to teach his classes in a way they can relate to.

MERITT: I’ve brought King Salmon in, filleted them on the table, show kids the bone structure, the spine, and we’ve talked about the skin. If I catch a grey wolf when I’m trapping I’ll bring the whole thing right into the classroom, set it on the table, and we’ll look at his paws, his teeth, anyhow we do all sorts of dingdong things, we’ll bring in an octopus, sometimes I catch those in my shrimp pots we bring in an octopus check those out, it’s whatever’s around you bring in from the outside and it’s just a neat way to go with the kids.

FITZGERALD: Brian says that he takes each of his students out on his boat at least once during the school year. He knows his methods probably wouldn’t fly in any state other than Alaska, but that doesn’t bother him.

MERITT: Teachers contact me from California and say you know I’d be fired if I did that. I said well everybody knows me I’ve done it ever since I’ve taught I’ve been teaching for 25 years but it’s just an accepted thing in Wrangell, that’s how we teach science, that’s what the kids get to do, never had a complaint, ever, that I’m aware of.

The harbor in Wrangell (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: With the school year about to start, Brian is in full fishing mode. In a couple of days he’ll be heading out for King Salmon, the most coveted of the salmon species in Alaska.

MERITT: I’ll get up at like 2:30 in the morning, take off in the dark, run for an hour, start putting my gear in the water just as it breaks daylight. You’ll fish all day till at least 9 - 9:30 whenever it starts to get dark. Usually anchored up by 11o’clock sometimes 10:30, and then 2:30 - 3 day starts again, charge back out, and you will do that day after day as long as you’re catching King Salmon. Nothing is better than that. I mean you live for that.

FITZGERALD: Brian’s fishing boat is versatile. Sometimes he uses it to set a gillnet near the mouths of rivers like the Stikine, waiting to catch salmon as they swim upstream to spawn. But more often he’s trolling out in the open ocean, dragging long lines with baited hooks behind the boat. It’s not the most efficient way to fish.

MERITT: You catch 1/20th the amount of fish trolling that you do gillnetting.

FITZGERALD: But Brian says nothing beats the thrill of trolling for King Salmon. You have to pick the right tackle, set your line at the proper depth, and fight to land the fish once they bite. Brian says it’s almost like sportfishing, except you’re making money.

MERITT: It’s the game of the mind. It’s the challenge of it, and of course King salmon are worth 70 to 100 dollars apiece, versus a Dog Salmon’s worth 6 dollars. So you’re targeting the high dollar fish.

FITZGERALD: Though Kings are the highest-dollar salmon; they’re also the scarcest. To supplement the wild stock, the State of Alaska and British Columbia release King Salmon reared in hatcheries. Alaska and BC have also set tight fishing regulations, allowing only small windows when you can fish for Kings. This Thursday is the beginning of the only King Salmon window this month.

A Tlingit totem pole in Wrangell (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

MERITT: And if it’s blowing like a dog on Thursday most guys are going to tear off shore, and try to get to the fish, and crash boom bash it’s dangerous, but you only got three days to catch these Kings in August. So anyway that’s going to be the danger factor.

FITZGERALD: Brian says that most fishermen in Wrangell understand that this kind of regulation is needed to protect the species they depend on. Environmentalism can be a dirty word in a deep red, oil-rich state like Alaska, but Brian says fisherman know a threat to salmon when they see one, and mining development in British Columbia has him worried too.

MERITT: You know, I’m not opposed to using some of those resources, but when we’re talking about a mine and something might affect a major rivershed, then all of a sudden my opinion changes greatly.

FITZGERALD: The new mines still have serious financing hurdles to clear, but Imperial Metals, the owner of the Red Chris mine, could begin operations in early 2015. Imperial also owns the Mt. Polley Mine, where a tailings dam breach in the summer of 2014 sent massive amounts of toxic mining waste into the salmon-rich Fraser River. Tis Peterman is a Tlingit activist. She says that when she saw the video of the Mt. Polley spill, she couldn’t stop thinking about something like that happening on the Stikine. She says a spill like that could wipe out her small fishing town.

PETERMAN: As one elder told us, you want fish or you want mining? You can’t have both. And the fish is the base of our culture.

FITZGERALD: Tis says that the river has the power to unite people who haven’t always been allies.

PETERMAN: And this is the first time I’ve ever seen the commercial fisherman, subsistence fisherman, tribes, all on the same page. We all can see the potential devastation this stuff can cause.

FITZGERALD: Einar Haasath, a Tlingit elder, says that with the timber industry gone, Wrangell can’t afford to put the fishing industry at risk.

Shakes Lake, filled with icebergs that calved off of Shakes Glacier (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

HAASATH: If you lost the fishing industry you wouldn’t have anything. It would be a ghost town.

FITZGERALD: But for Einar, the need to protect the Stikine, one of the last great wild rivers and the river he grew up on, goes well its economic value.

HAASATH: The river is greatly important. And I would hate to see anything happen to it. People talk about industry and that sort of thing. Well, industry comes and goes, but a river, by golly, once you destroy it, it’s gone. You can’t bring it back.

FITZGERALD: The river and its riches made Wrangell possible, and for this little town on the edge of a continent to survive and thrive, the mighty Stikine may still be the key.

For Living on Earth, this is Emmett FitzGerald in Wrangell, Alaska.

Related links:

- Read more about the city of Wrangell, Alaska

- Video of the Tahltan blockade of the Red Chris mine

- Thanks to Trout Unlimited in Southeast Alaska

[MUSIC: Flurries, Soulive, Next, BlueNote Records, 2002]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Shannon Kelleher, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Thanks this week to Trout Unlimited and Nimmo Bay Wilderness Resort in Canada. Our show was engineered by Jake Rego, with help from Noel Flatt, and Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Kendeda Fund, and Trinity University Press, publisher of Moral Ground; Ethical Action for a Planet In Peril, 80 visionaries who agree with Pope Francis, climate change is a moral issue for each of us, TUPress.org, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth