October 30, 2015

Air Date: October 30, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Better Office Air Makes For Better Thinking

View the page for this story

Architects have long focused on ways to seal buildings up and make them more energy efficient, but new research demonstrates that good ventilation can be important for our cognitive abilities. Steve Curwood speaks with Harvard School of Public Health professor Joe Allen about the new study that documents the details and with John Mandyck of United Technologies about how the findings could influence the future of building design. (12:35)

Building a Sanctuary for Endangered Bats

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

Bats around the country are struggling to cope with the invasive European fungus White Nose syndrome. But writer Don Mitchell is trying to help by turning his farm into a sanctuary for the endangered bats that live on his property. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald reports from the Champlain Valley of Vermont. (10:50)

Greening Death

View the page for this story

Each year, five million people die in the US. About half of them choose conventional burial and half choose cremation for their body, both methods that consume resources and pollute the air and earth. Now there’s a greener alternative on the horizon, the Urban Death Project. Katrina Spade, founder and executive director, explains Urban Death Project and tells host Steve Curwood how this environmentally-consciousness choice can bring meaning to death. (06:45)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about some scary studies: one warns that some major cities will soon be hot as hell, and another cautions that processed meat is a carcinogen, and red meat is a suspected carcinogen. Then, we look athe efforts by some states to send the EPA’s new Clean Air Rules to the grave; and we take a look back on a humpback whale’s rise to fame thirty years ago. (03:40)

The Living and Dead in Good Company

View the page for this story

Massachusetts’ Mount Auburn Cemetery is renowned as the final resting place for American luminaries including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Fannie Farmer, and Charles Sumner. But as America’s first garden cemetery, it’s also a brief home for migrating birds every spring and fall. John Harrison and Kim Nagy, co-authors of the book Dead in Good Company: A Celebration of Mount Auburn Cemetery walk through the cemetery with host Steve Curwood and observe the wildlife and visit the deceased. (14:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: John Mandyck, Joe Allen, Katrina Spade, John Harrison

REPORTERS: Emmett FitzGerald, Peter Dykstra,

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. New research suggests that if we improve indoor air quality we could dramatically boost workers’ ability to think and make decisions.

ALLEN: There's a positive story here. It’s that there are things we can do right now in most spaces that will reduce the chemical concentration that we're exposed to, and increase the amount of outdoor air coming in, and we think this will lead to better cognitive performance based on the results of this study.

CURWOOD: What we should do to help creativity and focus. Also, how a farmer scared of bats reshaped his land to give them sanctuary.

MITCHELL: They looked like a tiny Icarus, like a little tiny human being with wings. And I could look into their eyes and they could look into my eyes and I realized then that I had crossed some kind of a mental bridge and that now these were creatures I cared about.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

[THEME]

Better Office Air Makes For Better Thinking

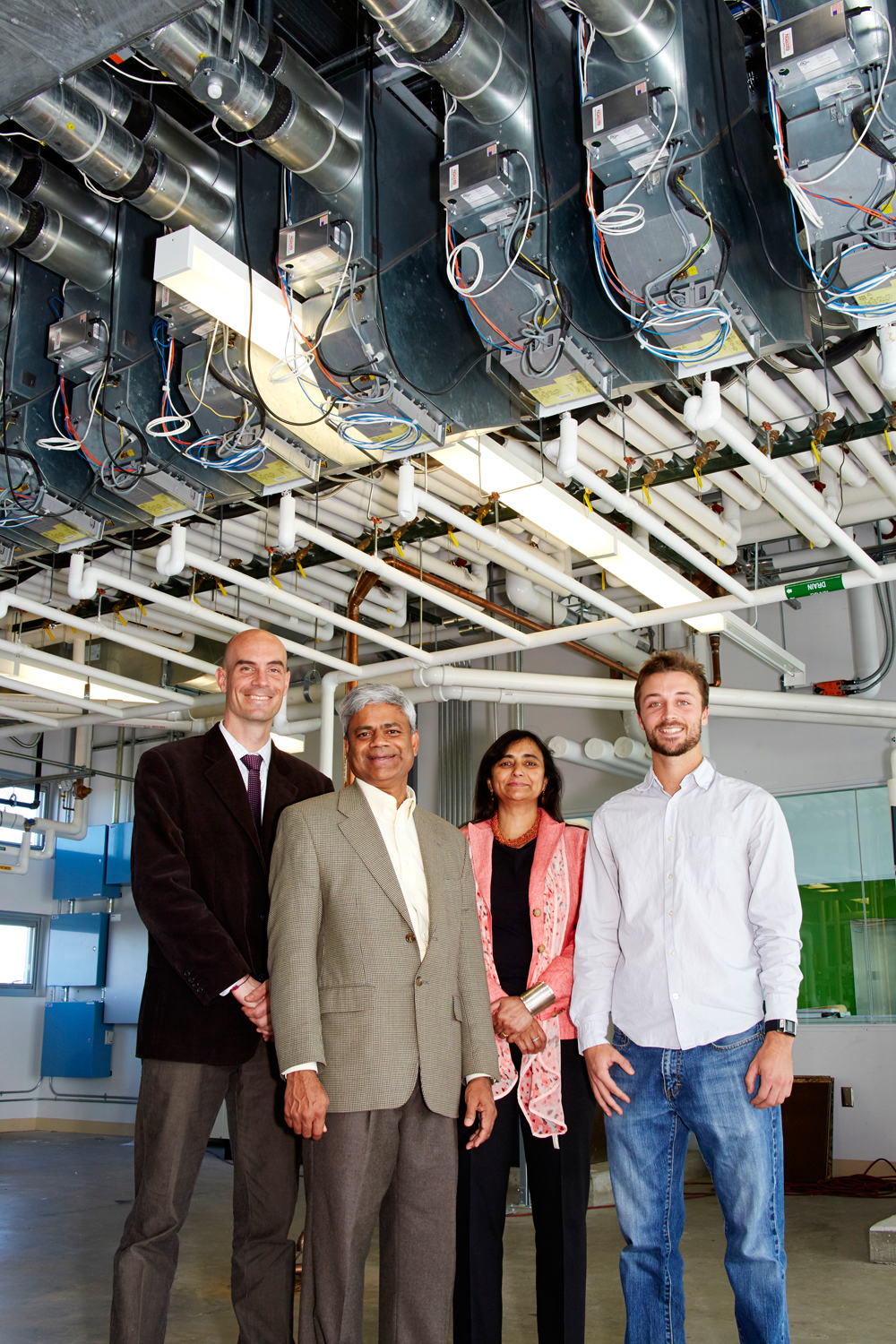

Twenty-four professionals participated in the six-day COGfx Study. Each conducted their normal work activities within a laboratory-setting that simulated conditions found in conventional and green buildings, as well as green buildings with enhanced ventilation. (Photo: United Technologies)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Think air quality and you’re likely to consider outdoor air, full of diesel fumes and smoke and dust. But most of us spend 90 percent of our time inside. Now ground-breaking research by a team from Harvard, Syracuse University and SUNY Upstate finds that dramatically improving indoor air quality can more than double the reasoning scores of workers. Chemicals found in paints, furniture and flooring, so-called volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, are the main problems. And common office concentrations of carbon dioxide also modestly reduce cognitive functioning. The lead author of the study, published in Environmental Health Perspectives is Joe Allen of Harvard’s Center for Global Health and the Environment. Welcome to Living on Earth, Professor Allen.

ALLEN: It's a pleasure to be here. Thanks.

CURWOOD: Your study looks at the impact of indoor air quality on cognitive functioning, so tell me about the study. How did you do this?

ALLEN: We set up in the Syracuse Center of Excellence. They have a simulated office environment, and we enrolled what we called knowledge workers, people who work in office environments. We enrolled them to come to the Syracuse Center of Excellence and do their normal work routine in this office. From the floor below, we were able to manipulate the indoor environmental conditions in their workspace unbeknownst to them. At the end of each day, we administered a cognitive performance test, and the analysts are also blinded to the conditions that were testing that day, so that way it's a double-blinded study, it's a controlled environment, and we were able to manipulate one variable at a time to tease out the effect of that variable on the cognitive performance scores of people in that space.

CURWOOD: Now, how did you measure the cognitive impacts?

ALLEN: So we measured cognitive performance with a great tool called the simulated management strategy tool, and it's a neat tool because it tests real world decision-making performance. I think it's best if I give you an example. So, in one of the scenarios, the participants are asked to play a game, and they are essentially the mayor of a city, and in that role they are prompted with things that happen throughout the day and they have to respond to these prompts throughout the day, and they have a wide axis to a wide range of information, and we watch how they plan, strategize and what decisions they ultimately make in response to the information coming at them.

The research team responsible for the study (From left) Principal Investigator Joseph G. Allen, DSc, MPH, Assistant Professor of Exposure Assessment Science, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Co-investigator Suresh Santanam, ScD, PE and Associate Professor of Biomedical and Chemical Engineering, Syracuse University; Co-investigator Usha Satish, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, SUNY Upstate Medical University; and Project Manager Piers MacNaughton, MS, doctoral candidate, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (Photo: United Technologies)

It's really similar to how we all operate every day. You're sitting at your desk, you have access to unlimited information with the Internet, your phone rings, you have text messages coming in, you're answering e-mails, the boss comes in, a crisis happens, and we want to simulate this with this tool to test how people respond under this real-world scenario of dealing with information, figuring out how to use information, are they optimized, how they do in a crisis and importantly, how do you recover after a crisis, are you done for the day or do you go back to your nice strategic planning in taking actions based on the prompts are coming in.

CURWOOD: So what did you find? How did people perform these cognitive tests based on their exposure to changes in air quality?

ALLEN: Yeah, we found some quite striking results. We found a doubling of cognitive performance scores for people who spent time in the optimized green building environment compared to those same people when they were in the conventional office building, an indoor environment designed to simulate the conventional office building. And three domains, three cognitive functioning domains in particular had the strongest scores. These were crisis response, strategy, and information usage. And these three cognitive function domains are most closely tied to productivity.

CURWOOD: Those numbers are huge. That's a big disparity. How surprised were you by those findings?

ALLEN: To be quite honest, we were shocked. We think this is a big deal, that the findings are strong, the magnitude of the effect is quite large and the really nice thing about the studies is that we weren't testing anything exotic. We didn't introduce chemicals into the environment that you don't typically encounter. We didn't introduce ventilation rates that are impossible to obtain. The idea was to simulate office environments that can easily be obtained. So these are chemicals that we are commonly exposed to, these are outdoor ventilation rates we can obtain in most buildings. So this is what's shocking is that you see this big effect - the magnitude is big, and the effort it takes to reach that wasn't that much.

CURWOOD: Joe, how does all this indoor air pollution affect us physiologically? How do you get from the chemical to cognitive impairment?

ALLEN: Well, this is a great question and it's currently unknown, so there's no answer right now, but we hope and we know - there are people working on this and we're starting to work on it too - is the next question is why is this happening, or how is it happening...so physiologically, mechanistically what's happening that's causing this decrement or in some cases improvement in cognitive performance functioning. So we think that the next six to 12 months we'll start seeing a lot of researchers attacking that question.

CURWOOD: So let's be specific about these chemicals. What's the impact of the Volatile Organic Compounds, the VOCs?

The study was designed to determine the independent and combined effect of volatile organic compounds, ventilation and CO2 on workers’ cognitive function. These factors were controlled by a machine room located directly below the workspace. (Photo: United Technologies)

ALLEN: So VOCs...I mean, we're exposed to VOCs every day in just about every environment we're in, and we know they cause things like eye irritation or upper respiratory irritation, some of them are carcinogens, so we know these compounds can be irritants, and now we're learning that they can also impact cognitive function.

CURWOOD: Now, what about carbon dioxide?

ALLEN: Yeah this is very interesting. So, the second part of our study we looked at the impact of carbon dioxide on cognitive function, independent of ventilation - outdoor carbon dioxide concentrations are typically around 400 parts per million right now. Indoors, we routinely see carbon dioxide between 800 and 1,200 parts per million, but it's not uncommon to see carbon dioxide as high as 1,500 parts per million or even up to 3,000 parts per million. So we found in our study is that when people were in an environment with low-carbon dioxide concentrations and they were moved to a level of about 950 parts per million, a level we find in most indoor spaces, we see a 15 percent decrease in cognitive performance scores for the people in that space, and when they move to an environment with 1,400 parts per million, we saw 50 percent lower cognitive performance scores when they were in that environment.

CURWOOD: So, a huge impact.

ALLEN: Yeah, very big. I mean this is new for our field. Carbon dioxide, we measure it all the time when we're doing studies of buildings and health because it's a good indicator of how well the space is ventilated. But now we’re starting to see that maybe carbon dioxide isn't just this useful tool as a proxy for ventilation and other things that are building up in our environment. It might actually be a direct pollutant, a primary pollutant.

CURWOOD: So you say that there's this is decrease in cognitive functioning when you have poor air quality or even conventional office air quality compared to greener air quality. How do you translate that into dollars and cents, let's say, for a company looking at its workers?

ALLEN: Yeah, I'll tell you about our next paper that we publish that should be out in the next month or two because we thought this was a really important question to ask is how can we take the data we have now on cognitive performance and turn it into dollars because we know that research informs practice, and what a lot of these practitioners want to hear is how is it going to impact my bottom line. So we looked at the energy penalty, or the energy cost for increasing outer air ventilation to the levels we did in the study where we found a benefit of cognitive performance and we find that it's on the order of $30 per person per year to double your outdoor air ventilation rate. Then we used the same information from our study and look at the cognitive performance improvements normalized to what we find in the general population and we estimate that the benefits to productivity are on the order of $6,000 per person per year.

CURWOOD: So what do you hope comes out of this study?

ALLEN: We designed the study specifically to look at what building factors could be improved that would lead to benefits to cognitive performance of people in that space, and there's a positive story here is that there are things we can do right now in most spaces that will reduce the chemical concentration that we're exposed to and can increase the amount of air coming in, and we think this will lead to better cognitive performance based on the results of the study.

CURWOOD: You know, when you do a home energy audit, they come and they do this pressure test to see how much leakage you have, and the less leakage you have the more efficient the home is. To what extent is this a zero sum game if you improve indoor air quality, you have less energy efficiency?

ALLEN: Yeah, Steve, I think it's a false choice we've been given over the past 30 years where there has been a trade-off traditionally between energy efficiency and human health, and that can't be the way we move forward. And we know that you can make decisions now in how buildings are designed and how your ventilation system is performing and the choices in the products you make can be used to optimize indoor environmental quality while optimizing energy performance and cost.

CURWOOD: Joe Allen is an Assistant Professor of Exposure Assessment Science at the Harvard T.H. Chan school of Public Health. Thank you so much.

ALLEN: My pleasure. Thank you.

CURWOOD: For an industrial perspective on the implications of this Harvard-led research we turn now to John Mandyck, chief sustainability officer for the United Technologies Corporation. UTC is the world’s largest provider of building technologies, and the key underwriter of the study, but was not involved in the data collection, analysis, interpretation, or drafting of the peer-reviewed paper. John Mandyck says these findings may revolutionize the way we think about buildings.

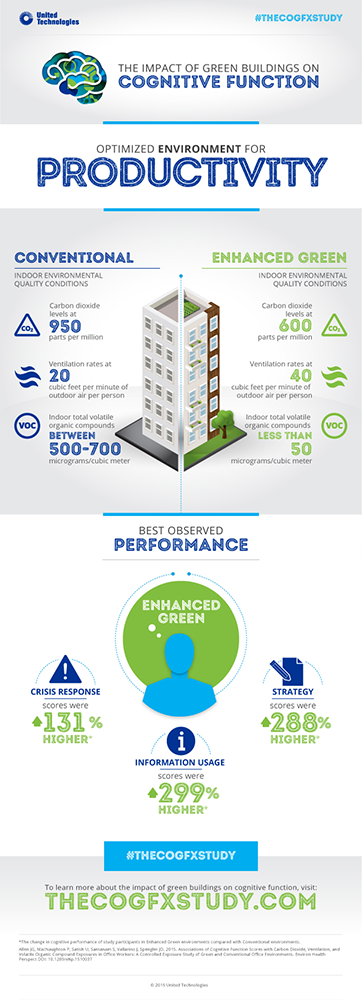

Infographic of the results (Photo: United Technologies)

MANDYCK: The study that Harvard and its research partners has done has the potential to change everything for how we think about buildings. We have to have the laboratory basis of the analysis to set the baseline. Now with that baseline which is a very, very strong baseline and the correlation of green buildings and cognitive impact, we're now going to test that baseline in 10 buildings around the country.

CURWOOD: How might this“change everything”to use your words?

MANDYCK: I think this can change everything because better thinking and better buildings means buildings can become competitive assets for companies. It's a way that companies can differentiate themselves to get a competitive advantage. Think about this: the research that Harvard and its study partners have found is that with optimized indoor environmental quality, test scores over nine cognitive domains doubled. That really means better thinking in better buildings, and I think what's most important here is that productivity often comes with a learning curve. In this case, all people have to do is breathe because the intelligence is in the air with the optimal and readily achievable conditions that Harvard and its study partners found in this research.

CURWOOD: Now, for years, people sold building energy efficiency on the basis of payback because you could see the math, you put in so much insulation you save so much in terms of using fossil fuel, and you could see the money going right to the bottom line. How does this study, how does this research, help you sell better quality with a measurable payback?

MANDYCK: Well the basis for the research is to accelerate the green building movement overall. As you pointed out, energy has been a very important value mechanism in ways that we approach green buildings, that if we build green buildings they save energy, they save water and you receive a natural pay back from that. We've done very well with that type of analysis. Last year, the green building market for the commercial sector in the United States reached about 47 percent. So we've come very, very far, but the interesting thing here if you look at the true cost of operating a building, just one percent is energy. Ninety percent of the true operating cost of a building are the salaries and the benefits of the people inside the building. Green buildings can improve thinking, can improve productivity, can improve health. Buildings can become human resource tools now. Buildings can become ways that we can find competitive advantages simply by optimizing the indoor environmental quality.

CURWOOD: John Mandyck is the Chief Sustainability Officer of United Technologies. And by the way, UTC is also a supporter of Living on Earth. There are more details at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Study: The Impact of Green Buildings on Cognitive Function

- More about the study and its implications from United Technologies

[MUSIC: J.S. Bach, “Air On a G String,” from Orchestral Suite No.3 in D, transcribed and performed by Xuefei Yang, live in WGBH Fraser Studio, 2012.]

CURWOOD: Just ahead... death and regeneration. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gently Drowning by Beat Frequency. Public domain video footage from archive.org 2008]

Building a Sanctuary for Endangered Bats

Indiana bat (Photo: Adam Mann/USFWS)

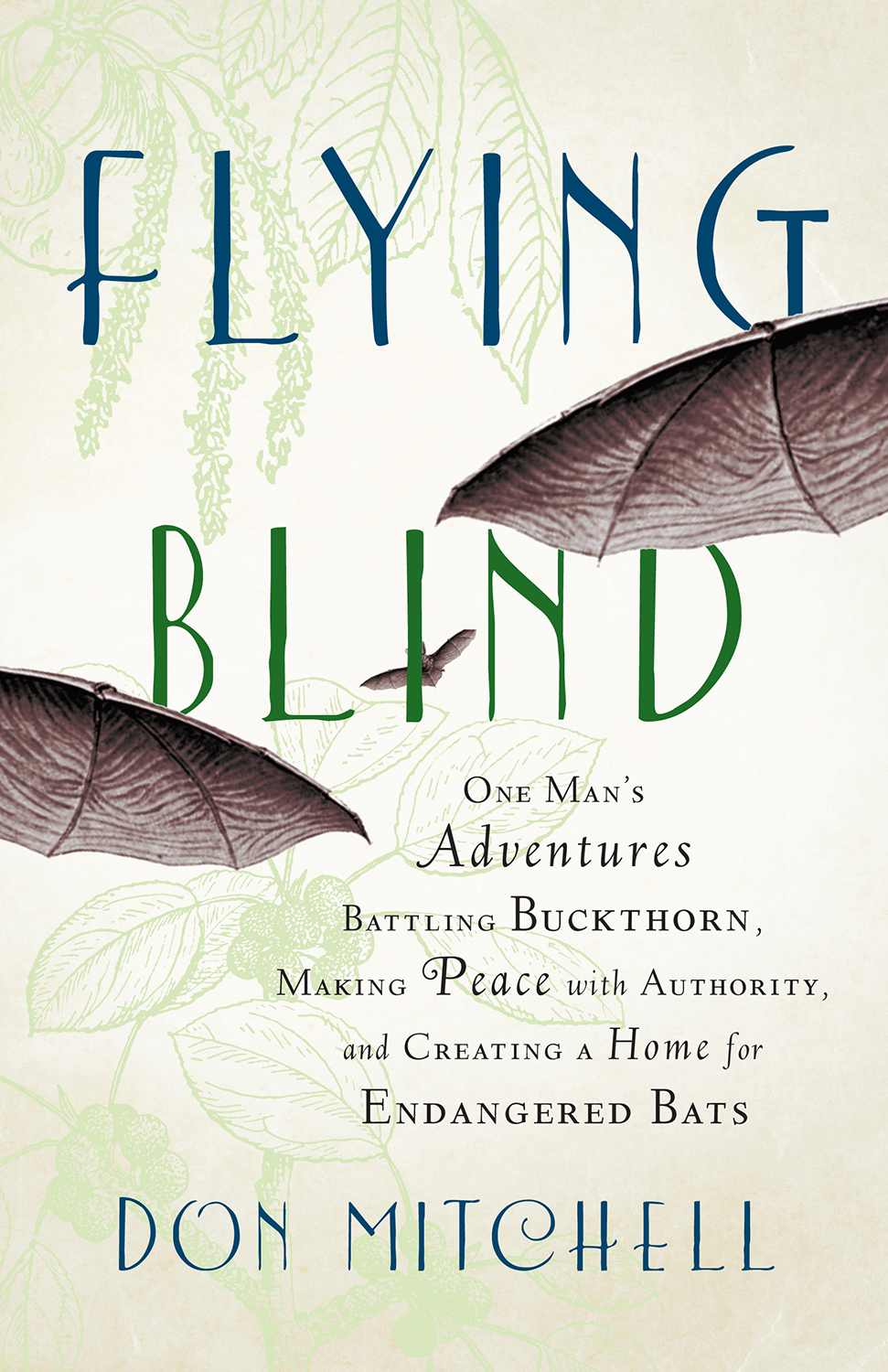

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Halloween sees the end of Bat Week – a nice fit for these spooky, and sometimes blood-sucking creatures. But in North America and Europe, these scary night-fliers eat huge amounts of harmful insects instead. North American bat numbers have plummeted in recent years though, due to a fungal disease called White Nose syndrome. So conservationists are doing all they can to help keep bats around. Don Mitchell is a writer and Vermont farmer whose memoir Flying Blind, documents his efforts to turn Treleven Farm into an endangered bat sanctuary. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald has the story.

FITZGERALD: Don Mitchell hasn’t always loved bats. Quite the opposite actually.

MITCHELL: I knew I disliked bats around 1975 when we found one in our bedroom flapping about our heads at night. And my instinctive reaction was one of fear.

Walking through the bat territories with Don Mitchell and Scott Darling (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: But one day, a man named Scott Darling from Fish and Wildlife showed up at Treleven Farm, and told Don that he had endangered Indiana bats living on the property. Don wasn’t particularly concerned about their wellbeing at first, but he saw an opportunity to lower his tax rate.

MITCHELL: I learned that I could create a forest management plan to put the farm into a tax abatement program, by foregrounding the fact that we had habitat for an endangered species.

FITZGERALD: Then he discovered that with a small amount of state funding he could actually enhance the habitat for bats, and increase his chances of getting the tax break.

MITCHELL: So my reasons for getting involved were entirely self-interested, selfish from the beginning. And I guess I became a believer.

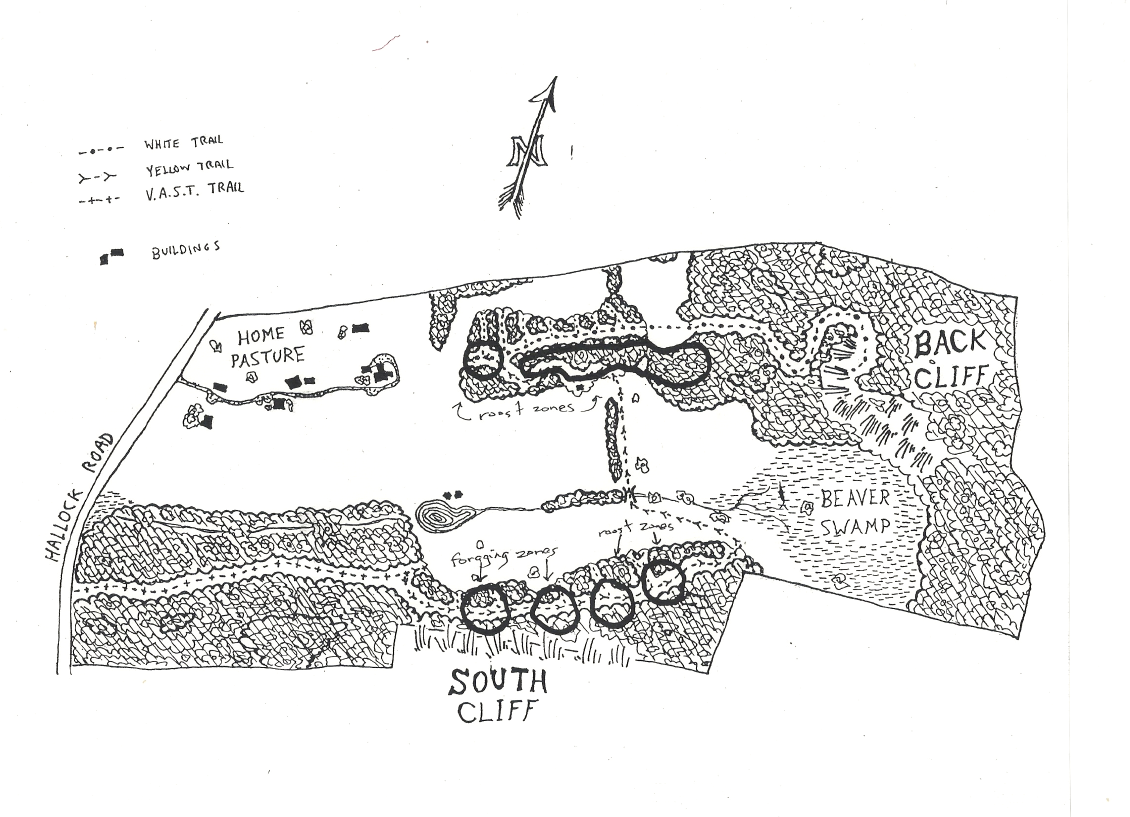

FITZGERALD: Don set about transforming five acres of field and forest on his farm in the Champlain Valley into sanctuary for Indiana bats. And Scott Darling gave him advice.

DARLING: We suggested to Don that he focus on roosting habitat, as well as try to provide some improved foraging habitat, so there would be areas where these bats could forage in somewhat of an open understory but still within a forest canopy.

Left to right: Don Mitchell’s daughter-in-law Susannah McCandless, Scott Darling, and Don Mitchell (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: It was an ambitious, sometimes backbreaking project, and Don is proud to show off his renovated bat territories to Scott and me.

[SOUNDS OF WALKING]

FITZGERALD: First we come to the roosting zone. Indiana bats are about two inches long and covered in chestnut colored fur. They usually sleep upside down in dead and dying trees, but Scott says that in Vermont they also like a species called the shagbark hickory.

DARLING: And they have these bark features, this almost peeling bark, that to an Indiana bat looks like a dead, and dying tree, and they can tuck themselves right under the bark and be very warm during the day, sleep protected from rain, and still be able to readily fly on out and forage at night.

FITZGERALD: Don had lots of shagbark hickories on the property, and as part of the management plan they submitted to the state, Scott recommended that he try to promote the growth of shagbarks in particular roosting zones. But to meet the state’s requirements, first Don had to eradicate all of the invasive species in the plot, plants like garlic mustard and buckthorn.

MITCHELL: These invasives they have the most amazing strategies, the garlic mustard will actually put what amounts to a poison in the soil that inhibits other plants from growing there, so it tends to colonize the forest floor. The buckthorn produces a seed, a berry that birds love to eat, and its cathartic so the birds get diarrhea when they eat it and poop out the seeds far and wide.

FITZGERALD: Clearing all these plants was a grueling process, but when Don had finished, the state gave him permission to “release” the shagbark hickories.

MITCHELL: To release them means to remove, to take down some of the forest canopy that surrounds them, to optimize their use by bats.

Shagbark hickories are great roosting habitats for endangered Indiana bats. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Judging by Scott’s reaction today, Don did a pretty good job.

DARLING: Oh wow, I don’t know – yeah you know what the problem is, there’s too many to choose from now. Look at that! Some of these trees, their bark is a little different, see this one look at that piece, its like woahhhh you could put 20 bats in there!

FITZGERALD: So kind of the shaggier the better?

DARLING: Yeah the shaggier the better. Wowww that is beautiful.

FITZGERALD: Scott is excited to see good habitat like this. Bats in Vermont have been dying out en masse due to the invasive European fungal disease, White Nose syndrome.

DARLING: The hyphae from the fungus actually invade into the skin tissue, particularly near the wings, and begin to eat away at the tissue.

FITZGERALD: The fungus thrives in damp caves and mines where bats spend the winter, and began affecting hibernating bats about seven years ago.

DARLING: And eventually most of these bats would flee from the cave or mine, literally in the middle of January when no bat could survive outside, and they were dying across the landscape when White Nose syndrome first hit.

Scott and Don at the edge of the pond (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: White Nose was first discovered in a cave in New York in 2007. It showed up in Vermont in January of 2008.

DARLING: And what’s amazing is by 2010 we estimate we’d lost about 90 percent of our little brown bats and 90 percent of our Northern Long-eared bats, all in that two to three year window.

FITZGERALD: It’s a catastrophic decline. Since then Vermont’s Indiana and little brown bat populations have begun to stabilize, while long-eared bats continue to struggle with White-nose. Darling says the goal at this point is to keep the much-diminished bat populations afloat until either scientists can find a cure to white-nose, or the bats develop a natural resistance.

DARLING: We want to really minimize any other forms of mortality on our bat population, we know that they are being exposed to this disease. We’re really working to try to maintain again a good supply of dead and dying trees, good foraging habitat, good clean supplies of water, those are all going to be important in keeping that foundation of that population going. You know once you’ve lost it, there’s no going back.

FITZGERALD: Shall we keep walking?

[WALKING]

FITZGERALD: We cross through a meadow to a forest on the other side of the farm.

Entering the bat zones (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

MITCHELL: So now Scott can tell we’re entering the foraging zone. Which means that every tree less than seven inches in diameter at breast height was removed, to give the bats an easier time cruising around catching insects at night. We call this the all-night diner.

FITZGERALD: Bats tend to forage around the edge of the woods, which is dangerous because they’re exposed to predators like owls. But in here, they have enough room to cruise around and hunt for bugs under the safety of the forest canopy. This was Scott’s idea, but Don made it happen.

MITCHELL: Isn’t this beautiful. Oh my God, yeah. There’s so much more wildlife in here small birds and mammals and stuff.

DARLING: But here’s this case where these bats can forage in here really relatively easily, and still be under forest cover. This is really, from what we know about Indiana bats, from what I’ve observed about Indiana bats foraging, these are the conditions that are going to make it right.

FITZGERALD: Don says the key to this project is providing everything a bat needs in a relatively small amount of space.

Don Mitchell next to a shagbark hickory (Photo: Ethan Mitchell, Chelsea Green)

MITCHELL: Imagine for us if your home was in Middlebury and you had to go to Burlington to eat and you had to go to Montpelier for a drink of water, life would not be so simple. So trying to optimize habitat involves placing all the things that a creature needs in a reasonably constricted zone.

[WALKING]

FITZGERALD: As we walk back to the farmhouse Scott says he couldn’t be happier with how things are looking.

DARLING: We’ve actually increased habitat for a bat, and when you do that you increase its reproduction, its survival rates you do all these other things that affect populations positively.

FITZGERALD: Scott says it’s hard to be optimistic about the future of bats in the face of a disease as devastating as White Nose syndrome, but landowners like Don give him hope.

DARLING: People caring for the land and caring for a species of bats and making a difference. White Nose syndrome is the battle for bats, and this is one way that not just biologists but landowners can fight back as well.

FITZGERALD: Scientists still don’t know what the final impact of White-nose will be on the overall ecosystem. Bats are the primary nighttime predator for insects in Vermont, and losing 90% of them is bound to have ripple effects.

Hand-drawn map of the bat habitat (Photo: Don and Ethan Mitchell)

DARLING: My argument has always been that the wise person just doesn’t take away that one element, the bats there, and assume that everything will stay intact. So it’s just keeping all the pieces that’s really important. And this disease, this invasive disease, that has really affected one of those pieces, may well have implications we just know about.

FITZGERALD: Don Mitchell is doing his part to keep that piece around. He worked this land for decades without giving any thought to the bats that shared it with him. Then they became the focus of countless hours pulling buckthorn to make way for shagbark hickories. But he isn’t sure what the fruits of all that labor will be.

MITCHELL: One of the reasons the book is titled Flying Blind is because I think when we set out to tamper with the ecosystem for one narrowly defined goal or another, we often don’t have a keen sense of vision for what where we’re going or what we’re doing, and our goals change almost every generation, so we should do this with humility.

Flying Blind (Photo: Chelsea Green)

FITZGERALD: No matter what happens, Don says his opinion of bats has certainly changed. A few years ago he had the chance to hold a couple that Scott had trapped at night.

MITCHELL: They looked like a tiny Icarus, like a tiny little human being with wings. And I could look into their eyes and they could look into my eyes and some kind of transaction like ‘we’re both mammals here’ was taking place. I realized then that I had crossed some kind of a mental bridge, that now these were creatures that I cared about.

FITZGERALD: For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett FitzGerald in the Champlain Valley of Vermont.

CURWOOD: Don Mitchell’s memoir is called Flying Blind. There’s more at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Treleven Farm

- Don Mitchell’s book Flying Blind from Chelsea Green

- More about White Nose syndrome from the National Wildlife Health Center

[MUSIC: The Twilight Zone Theme/ La quatrième dimension,” written by Bernard Herrmann/Marius Constant, performed by TV Philharmonic Orchestra.]

Greening Death

The Urban Death Project proposes that, after a ceremony, families lay the deceased in a field of woodchips. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

CURWOOD: For thousands of years our ancestors have been laying the dead to rest and not much has changed. The departed were usually laid in the earth or on a funeral pyre. Those are still the most common methods today. But a new paradigm is on offer.

SPADE: The Urban Death Project is an alternative to cremation and burial that uses the process of composting to turn us into soil.

CURWOOD: Katrina Spade is founder and director of the Urban Death Project. The concept came to her when she was doing a master’s degree in architecture and started to think about mortality – and what happens next.

SPADE: I started looking into the options that we have available in this culture, and for the most part, it's conventional burial with embalming in casket and grave liner or cremation. But in researching it I found that it does, of course, burn fossil fuels and all the cremations in the US are the equivalent of 70,000 cars driving the road for a year. You know, it is a significant source of pollution, but I think we're importantly it doesn't hold particular meaning or relevance for me and I think for lots of people in our culture we choose it because it's kind of the best option there is, and so being in architecture school I thought maybe I could set out to design another option that would be meaningful for more people.

Compost from the Urban Death Project would be used for gardens on the premises, in local parks, and families could take some and spread it in a place special to them or the deceased. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

CURWOOD: So what does your design look like and how does it incorporate elements of meaningfulness and environment consciousness?

SPADE: Well, the Urban Death Project is a proposed type of programming for our cities and to me the reason that composting oneself is meaningful is due to the fact that rather than destroying the nutrients in our body after we've died that we've been kind of collecting over the years that we've been living on this earth, we're able to be productive one final time and use those nutrients to grow new life. So the meaning for me is very much in the process itself.

CURWOOD: So if someone were to decide this is how they want their remains handled, what's the process you would use here?

SPADE: Well, let me back up a little bit because when I was in graduate school thinking about my impending mortality, I stumbled upon research done into livestock mortality composting. So there's been a bunch of agricultural institutions including Cornell and Washington State University, and what they find is that if you lie a high carbon material down, about two feet of wood chips for example, or wood chips and sawdust sometimes, put the animal on top and lay another two feet of the same high carbon material over the top the animal in about 3 to 6 months, the animal has completely composted, including the bones. So you're creating the environment, so that the microbes and beneficial bacteria can do their job. So that environment includes the right ratio of carbon and nitrogen. It also includes oxygen and moisture.

Each year, millions of resources go into caring for our dead in the US. The Urban Death Project plans to cut that number significantly. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

CURWOOD: So now, it's one thing to do this with a cow. People would be a different situation because you can't pile this bit of carboniferous material on top of the departed Flossy in the back 40 there. People tend to be more formal. What are you suggesting people do?

SPADE: So, as an architecture student my job was to take this research into livestock composting and redesign it for the human experience. So, what I've designed are buildings inside of which there is a three-story core where the composting process takes place, and around the core is a series of ramps. The living carry the dead up to the top of the core. There is an individual ceremony and a memorial service that occurs and then bodies are stacked vertically in this core and they're separated by about 10 feet of wood chips. In the second stage of the process after the bodies have turned to a coarse compost will have a screening and a sorting, for example, golden teeth or titanium hips, and with gravity and the settling and decomposition of the material, they actually travel downwards in the core and then the coarse compost will be refined and finished and cured. So it's very much still a natural process and I've tried to keep it as simple as possible. One of the most amazing things to me is the fact that families by doing this are actually beginning the transformation of their deceased from human to soil and to me that's quite beautiful.

Using this composting renewal system, Spade’s group estimates that it will take 4-6 weeks for a body to fully compost. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

CURWOOD: Katrina, in your process, when the composting is done, how are relatives going know which of the soil that’s been created is really Aunt Martha?

SPADE: At this point, there is no individual output. So that's a decision that I made early on in part because we're all part of a greater ecosystem, and so I just don't feel that it's necessary for us to have our individual person’s soil.

In Spade’s design, the living will carry the dead up 3 stories using ramps that wrap around the composting core. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

CURWOOD: How long does your process take?

SPADE: Well one of the things that we're figuring hearing out with our partners at Western Carolina University is exactly how long it will take for a human to decompose, and so were estimating right now about 4 to 6 weeks, but we still figuring out the details.

CURWOOD: Since we just can't compost a body anywhere, what legal or design issues do you think still need to be worked out?

SPADE: How you can treat a body after death is regulated on the state level. So, most states allow conventional burial, cremation, sometimes natural burial and often donation to science. What it's about is adding the method of composting to that list on a state-by-state level, but down the road if you really want to know what I envision is that death care would be part of our healthcare continuum, it would be free and available to all people, and that it would be municipally run. These places would be public spaces in our cities much like our library system or library branch.

CURWOOD: How do you think our views about ecologically conscious burial might influence the acceptance of human composting?

Urban Death Project founder and executive director Katrina Spade (in green) consults with scientists and planners to design each building and site. (Photo: the Urban Death Project)

SPADE: I think that the time is very right for this project. I've gotten such amazing support for it. I think that from an environmental perspective people are realizing that they don't want their last gesture to be polluting or wasteful. I guess I want to say also that it's really more about finding something that's meaningful, so if cremation is meaningful to you, by all means, it's a great choice because we pollute all the time during our daily lives. It would be really hypocritical of me to say you shouldn't do this one last little bit of pollution just because you died. I think the same thing is true for conventional burial, but the truth is that for so, so many neither of those options really resonates.

CURWOOD: Katrina Spade is the Founder and Executive Director of the Urban Death Project in Seattle. Thank you so much, Katrina.

SPADE: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- The Urban Death Project

- More about the process, possible stigmas and the possible involvement of religion or spirituality

- Kickstarter: the Urban Death Project: Laying Our Loved Ones to Rest

- How to Die Green

- Promessa Organic AB: composting corpuses but in a different way

- Green Burial Council

- How to Be Eco-Friendly When You're Dead

[MUSIC: London Symphony Orchestra, Geoffrey Simon conductor, The Planets Op32 V11 Neptune the Mystic, Holst G, The Planets, Capriole 1991]

CURWOOD: Coming up...birds, wildlife, artistic inspiration – the joys of the first US garden cemetery. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: When the Saints Go Marching In, American Gospel hymn, performed by the Rebirth Brass Band on Do Whatcha Wanna, Mardi Gras Records, 1997.]

Beyond the Headlines

The World Health Organization warns that sausages and other processed meats are carcinogenic. (Photo: Alpha, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. In a moment, a walk through a living cemetery. But first we’ll dive beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra of the DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News. He’s on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter. Boo!

DYKSTRA: Happy Halloween, Steve.

CURWOOD: Well, So what’s in your goodie bag this week?

DYKSTRA: Let’s frighten the children with the flurry of peer-reviewed studies out recently. First, a little national-security-based climate research from MIT and Loyola Marymount University in the journal Nature Climate Change. Within decades, temperature increases in the Middle East could make major cities, including the holy city of Mecca, virtually unlivable, and the region potentially more unstable.

CURWOOD: Now that’s some scary stuff; have you got any more like that?

DYKSTRA: Two more. Economists from Stanford and Cal Berkeley published in the journal Nature on links they see between rising temperatures and damaged economies. Their study says climate change will also exacerbate the gaps between the world’s rich and poor nations and people. And finally from our house of academic horrors, the World Health Organization released a much-anticipated report in which they say that red meats are a probable carcinogen and processed meats are as certain a carcinogen as tobacco. But as is often the case with reports like this one, there’s some pushback on the level of cancer risk, and just exactly how much delicious bacon you’d need to eat to face such a risk.

The Obama Administration’s Clean Power Plan rules target energy produced by burning coal, a major source of air pollution in the U.S. (Photo: Cathy, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: And you can find links to these studies, and some pushback, and all our news on our website, LOE.org. So what’s next?

DYKSTRA: Last Friday, President Obama and the EPA published their new Clean Air Rules, and they’re being met with shrieks of horror from energy-reliant states, and a few states that maybe just don’t like President Obama and the EPA all that much. A total of twenty-seven states filed suit to block the new regs, and New Jersey became the 27th, as Governor Christie wanted to help with the legal roadblock. But some legal experts see the litigation as a sort of government Mischief Night, with little chance of sidelining the Clean Air Rules. As if to underscore that point, many of the twenty-seven litigious states are already making plans to comply with the very rules they’re fighting in court.

CURWOOD: Hmmm. Now every week, we take a trip back through environmental history. What’s on the calendar this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, a couple of weeks ago we talked about one of the great human interest whale stories of our time, the three gray whales trapped in the Arctic ice off Alaska. But this week is the 13th anniversary of another great whale story. Remember Humphrey, the Humpback Whale?

CURWOOD: Of course! Humphrey swam into San Francisco Bay and then all the way up the Sacramento River before turning around.

DYKSTRA: And in the process, became a rock star with a blowhole, all for making a few wrong turns. Humphrey first garnered attention after swimming under the Golden Gate bridge, then after checking out San Francisco Bay, he turned up the Sacramento River, into increasingly fresher, shallower water – no place for a forty-ton marine mammal. Media hovered, crowds gathered, and marine mammal rescuers banged pipes and tried everything to steer Humphrey back to the sea until finally, 67 miles inland, Humphrey turned around, leaving a media frenzy and a couple of children’s books in his wake.

CURWOOD: And as we often ask of vanished celebrities, where is he now?

DYKSTRA: Well, Humphrey returned in 1990, beaching himself in San Francisco Bay, and he had to be rescued off a mudflat by the Coast Guard, but he wasn’t spotted again after 1991. They can identify individual humpback whales by the markings on their tail flukes and flippers, but I have a theory on how they knew Humphrey was a male.

A plaque in Rio Vista, CA commemorates the visit of Humphrey the Humpback Whale to the Sacramento River in 1985. (Photo: Orin Zebest, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Oh? What’s that?

DYKSTRA: Well, a guy would be totally incapable of stopping to ask directions, right? Not peer-reviewed, but I think it’s pretty obvious.

CURWOOD: I should have seen that one coming! Peter Dykstra is with EHN dot org - that’s Environmental Health News - and the DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter! We’ll talk soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot, we’ll talk to you soon.

Related links:

- Persian Gulf may be too hot for human survival by 2090. Here’s what this means for your city.

- Study finds the warmer it gets, the more world economy hurts

- World Health Organization: Red and processed meats have a strong link to cancer

- Beefing With the World Health Organization’s Cancer Warnings

- States sue to block EPA’s pollution rule—even as some try to comply

- Humphrey, the Humpback Whale

[MUSIC: The Ballad of Gilligan’s Isle, written by Sherwood Schwartz and George Wyle, performed by The Hit Co. on The Instrumental TV Theme Collection, Vol. 2, Planet Music (publisher)]

The Living and Dead in Good Company

Leaves fall around headstones in Mount Auburn Cemetery. (Photo: Maureen Gilreath, Flickr CC BY-2.0)

CURWOOD: You might have trouble unraveling the common thread that links cookbook author Fannie Farmer, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner, but all three of these nineteenth century luminaries lie peacefully – we trust - in America’s first garden cemetery. And a new book, "Dead in Good Company,”celebrates not only the stories of these famous people, but also the wildlife that Mount Auburn cemetery is now famous for. On a crisp autumn day, I headed through cemetery’s wrought-iron gates to take a walk with the book’s creators, including co-editor John Harrison.

[BIRDSONG]

HARRISON: The idea was for this to be a gardens cemetery, when it was created in 1831 by Jacob Bigelow, and you can see from the hills and valleys, the bodies of water, it is very much different than any ordinary cemetery. In fact, growing up, every now and then, someone would mention, "Have you been to Mount Auburn cemetery" and I'd say, "Gee no I haven't" and in my mind I would say“a cemetery is a cemetery." But I did finally come here and that changed my life.

Spring arrives at Halcyon Lake, Mount Auburn Cemetery (Photo: Friends of Mount Auburn, Flickr public domain)

CURWOOD: So we're here in the cemetery and around your neck you have the strap of binoculars, which reminds me, I first really heard about this place as a birding spot.

HARRISON: Oh it is. It's a bird sanctuary and wildlife sanctuary in addition to birds, other wildlife also.

CURWOOD: So, why is it so popular with birders?

HARRISON: Well, first of all of, this is on the migration path, and if you come here in May it's like a carnival here. There are hundreds of people running around with binoculars, with cameras, looking up because these are birds you only see once a year coming up from the south. Birding is the kind of thing that once you get into, it gets under you skin.

Washington Tower in Mount Auburn Cemetery located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Architects Dr. Jacob Bigelow and Gridley J. F. Bryant constructed the building in 1852-54. (Photo: Daderot, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: The birders who are listening to us are going to say,“so what do you have on your list from being at Mount Auburn cemetery?”

HARRISON: On the list, just for instance how unusual this can be, one of the very best birds that you see at the spring migration is the Cape May Warbler. It's spectacular and all of my life here I'd be lucky to see one way up in a tree for a couple of seconds. This year they just happened to land, a bunch of them, because they fly all night and when the sun comes up, the first green place they see, they all descend. And they landed and spent several days here on Cedar Avenue, which is just unbelievable. There must have been 100, 150 people. For three days you could just look over your head and see three, four, five, six Cape May Warblers coming down to within three, four feet of you. Indigo Bunting is another special bird. They were visible this year. Then the regular, well, call them the usual suspects; the Magnolia warblers, the Vireos, Black-throated Green Warblers, Black-throated Blue, Chestnut-sided Warblers, and some years are slower than others, but this year was off the charts. It was just spectacular. People were out of their minds.

A red-tailed hawk—nicknamed “Lucy” by John Harrison—carries a spruce branch to her nest in Mount Auburn Cemetery, and her species inspired one of Harrison’s essays. (Photo: John Harrison)

CURWOOD: And what about the raptors?

HARRISON: Well we have a resident pair of Red-tailed Hawks. They're my favorite species since the beginning. This year they had two chicks. Just last week I happened to be here and the two siblings were chasing each other around. It was just beautiful. So they're always here. They're a regular part of the scene.

CURWOOD: So that's how they keep the squirrels down here, huh?

HARRISON: Yeah, that's exactly right. That's their favorite dish. Yep. I've been watching and you will see one swoop down on an unsuspecting squirrel and that's it.

Mount Auburn Cemetery is a popular stopover spot for migrating birds, including the Canada warbler. (Photo: Kim Nagy)

CURWOOD: So how big is this place and how many people are buried here?

HARRISON: I'd say 175 acres. There's about 100,000 people buried here.

CURWOOD: And there's some pretty famous people buried here, right?

HARRISON: Yes. Yes, indeed. Quite a few famous people. Jacob Bigelow, one of the founders of the cemeteries here and Bigelow chapel is named after him. Charles Bullfinch, the architect. Buckminster Fuller, Bucky Fuller's here. Curt Gowdy, the sportscaster of the Boston Red Sox. Winslow Homer. Bernard Malamud, the author, he's at Willow Pond. And I stumbled upon his grave myself. I didn't know that until I stumbled upon it. He's one of my favorites so I was glad to find that. Arthur Schlesinger Jr.'s here. BF Skinner. Henry Cabot Lodge. Edwin Booth, John Wilkes Booth's brother, he's here. There are senators, mayors, congressmen, judges, and I can't even keep up with all them. We're mostly...Kim and I...we're here for the wildlife.

CURWOOD: And Kim, of course, is your...

HARRISON: Co-editor.

CURWOOD: Co-editor. And both of you wrote some essays for this.

HARRISON: Yes, we each wrote an essay. Mine about Red-tailed hawks, and Kim specifically about the Great Horned Owl pair that appeared her first time here. It was that year 2011 when the Great Horned Owls had two owlets and we got to see up close and personal the lifecycle of this fantastic species.

CURWOOD: So, Kim Nagy, you are the co-author of this book, "Dead in Good Company: A Celebration of Mount Auburn Cemetery,”and you wrote about owls. Why?

The cemetery’s Washington Tower provides a 360-degree view of Boston and its surroundings. (Photo: Bill Damon, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

NAGY: Well, I likened the experience of the owls with an experience I was having with my mother who had moved here and had dementia and it was a tough time. What I found most interesting was that in watching the owlets grow, they were learning how to build a roadmap for their new life, and I was learning how to build a new roadmap for my current situation.

CURWOOD: So here you are in a cemetery building new life.

NAGY: Well, as Mount Auburn cemetery was created to change people's idea of death and burial and dying in 1831, with our book we wanted to show that this is not just a cemetery but it's a place of life, regeneration, regrowth, rebirth. And so to chronicle the lives of the owlets, we knew everything about them: their parents, we named them, and their first flight and everything else, we thought it was very apt.

A great horned owl. (Photo: Kim Nagy)

CURWOOD: So, hey, John so what do you mean by your book titled, "Dead in Good Company." Whose company is that?

HARRISON: Oh, all the souls that are buried here. All the spirits that are buried here. In fact, in preparing the book, Kim and I felt along the way because of all the challenges that we were able to meet and overcome that there's a spirit of Mount Auburn - that's what we called it.

CURWOOD: Can I ask you, is this place haunted?

HARRISON: If it's haunted, it's haunted in a good way. It's haunted by helpful spirits.

CURWOOD: Have you been here at night?

HARRISON: I was here one night after 11. Joe Martinez, one of our essayists who wrote about the spotted salamanders in the dell and the vernal pool, I was invited to come watch that develop. The night I was here you could shine a flashlight in the vernal pool and she these beautiful spotted yellow salamanders, and it is very different at night. It's a whole different experience.

CURWOOD: Spooky?

HARRISON: Not spooky. Just serene, but different, because it's dark. But it was beautiful.

Kim Nagy tells Steve Curwood about her favorite place in Mount Auburn Cemetery, the Consecration Dell where she watched owlets grow up. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

CURWOOD: What about the owls? [HOOTS]

HARRISON: Well, occasionally we would hear them at dusk. The security guards are here all night, are here through out the night, they often hear them and see them flying around. So there's more activity because they're nocturnal.

CURWOOD: So Charles Sumner, the famous Massachusetts senator, during the approach to the Civil War, is buried here, and let's walk over to his gravesite.

HARRISON: Sure.

[WALKING AND FOOTSTEPS]

HARRISON: There's a Red-tailed hawk, our guardian, flying over. It must be really great to be a Red-tailed hawk on a day like this.

CURWOOD: Indeed. So who knew 175 acres of beautiful gardens would become this key wildlife sanctuary for greater Boston?

HARRISON: Yeah, really, really in the center of the city. It's really amazing, but it's because of all the attention to detail. And all of trees, I mean, there are certain bird species like certain trees and certain berry trees and crabapple trees and there's something for all of them so when they do land here they stay for a while until they have enough energy to move on.

CURWOOD: So where are we now?

HARRISON: We're at the grave of Charles Sumner and William Martin whose essay, "The Actor and the Hawk", is the first in our book, is going to tell us a little about Charles Sumner.

CURWOOD: OK, Bill, what's the story you have for us?

MARTIN: Well, of course, you know that Sumner was one of the leading abolitionist voice in United States Senate in the run up to the Civil War, got himself caned on the floor of the United States Senate as a result of the speech that he gave calling out the senator from South Carolina and some people think that led to the war itself. He came home, he recovered, and after Lincoln was elected, Sumner became, you could say, the sharpest abolitionist thorn in Lincoln's side. On July 4, 1862, Sumner went to the White House to talk to Lincoln. He said to Lincoln that day,“Mr. President, on Independence Day it is time to give the American people a great gift, the gift of emancipation.”The war was not going well, Sumner understood that a new moral imperative had to be added if the north was to win the war, and Lincoln said to Sumner that day, "Senator, if I free the slaves, three more states will go out of the union, and half my officers will resign.”He was trying to walk a very fine line between men like Sumner who was speaking powerful moral truths to him and people on the other side of the political aisle in the north who were just trying to hold the union together "and we'll take care of that that slave issue later on." Lincoln told Sumner that day“emancipation is a thunderbolt that will keep.”He didn't tell Sumner however that he was already writing the Emancipation Proclamation, but the story gives you an idea of the moral voice that Sumner was and the fact that while Lincoln was a politician and couldn't say out right, "I hear you. I hear you," he heard him.

CURWOOD: How has the Mount Auburn cemetery inspired you and your work? You've written, what, ten books now?

MARTIN: A place like this for me because I write historical fiction, is probably more alive than it is to most people because the stories, like the one that I just told you about Charles Sumner, end up being dramatized in my novels, and so it's always a thrill to come where those people have their last resting place.

CURWOOD: Bill, you have an essay along these lines, it's in this book. Could you please read from your essay that opens this book?

Essayist Bill Martin walks with Steve Curwood to the grave of Charles Sumner. (Photo: John Harrison)

MARTIN: Sure.“Stories are everywhere in Mount Auburn cemetery. Beneath every marker and atop every monument, everyone who lies here lived as a character in his own drama. Some performed grand deeds others only dreamed them, but the moments they lived were as vivid, as colorful, as hot or cold as joyous or terrifying as any that we live now.”

CURWOOD: So, what's your favorite spot in the cemetery. John?

MARTIN: Let's see; my favorite spot is Weeping Beech at the RH White mausoleum, not too far from here because that's where I studied my first Red-tailed hawk, Lucy, which I wrote about my essay. It's always number one on my checklist when I'm here.

CURWOOD: And Kim Nagy, what's your favorite spot in Mount Auburn cemetery?

MARTIN: My favorite place in the cemetery is where the owls were in the dell. I think it's a great mysterious place. It's very beautiful and that's where the owls flew around right above the vernal pool.

CURWOOD: Bill, your favorite spot in Mount Auburn cemetery?

John Harrison talks with Steve Curwood at Mount Auburn Cemetery. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

MARTIN: My favorite spot in Mount Auburn cemetery is the top of the Washington tower from which you can get yourself a 360° view the hills of Massachusetts and Boston and the Charles River and Cambridge and all of the places that in so many ways form the landscape of my imagination, and one day we were here, my wife and I with John, on the top of the Washington tower and we were surrounded by young hawks all of them testing their wings, [HAWKS CALLING] and they were riding the updrafts all around us up there on the top of the tower, sweeping, screeching. And as I saw them doing this, I have to say I was thinking about the whole cycle of nature and something in Keats’ old Nightingale, and the quote that jumped to mind was,“Thou was not born for death immortal bird, No hungry generations tread thee down. [SOUND OF NIGHTINGALE SINGING] The voice I hear this passing night was heard in ancient days by emperor and clown.”The whole idea, of course, that we're down here on the ground amidst these magnificent monuments and yet nature's cycle continues and continues in the great circle of those hawks swooping around that tower.

CURWOOD: Bill Martin is the New York Times best-selling author of 10 novels and an award-winning PBS documentary and more. John Harrison is a book distributor and an avid photographer. He and Kim Nagy are co-editors of "Dead in Good Company: A Celebration of Mount Auburn Cemetery". John, Bill and Kim, thank you so much for taking the time today.

MARTIN: Thank you, it's been a pleasure.

HARRISON: And likewise, we appreciate that you allowed us to do this.

NAGY: Thanks so much, Steve.

Related links:

- Mount Auburn cemetery

- The world’s first garden cemetery, Pere Lachaise

- “Landscape Architecture and the ‘Rural’ Cemetery Movement”

- Dead in Good Company: A Celebration of Mount Auburn Cemetery

- Mount Auburn Cemetery is a Mass Audubon Important Bird Area

- The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner

- Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale”

[MUSIC: George Shearing,“Lullaby Of Birdland,” Youtube, 1987]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation and brought to you from the campus of the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, and Jennifer Marquis. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and John Jessoe. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Kendeda Fund and Trinity University Press, publisher of "Moral Ground: Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril". Eighty visionaries who agree with Pope Francis climate change is a moral issue for each of us. tupress.org. And Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth