February 19, 2016

Air Date: February 19, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Obama Calls For New Oil Tax

View the page for this story

President Obama recently called for a $10 per barrel fee for oil as part of his latest budget proposal. Such a tax is unlikely to make i make it through the current Republican-led Congress, but Oil Change International's Steve Kretzmann tells host Steve Curwood that it as well a Democratic bill to end the leasing of public lands for fossil fuel extraction sends a powerful message about the need to decarbonize economy. (07:50)

Beyond the Headlines

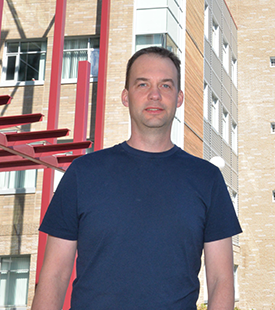

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about Aliso Canyon’s large greenhouse gas leaks and North Carolina’s odd concern over future waste from solar panels, before reflecting on the Boss Hog investigative project on North Carolina’s hog waste problem. (04:35)

Converting the Economy to Renewable Energy Without Big Batteries

View the page for this story

A new study from NOAA argues that within 15 years the U.S. could slash energy sector global warming emissions by 80%, keep consumer costs low and meet increased demand. What’s more we would not need battery storage but we’d have to build new high tech transmission lines,. Study coauthor and weather expert Alexander MacDonald tells host Steve Curwood that studying the national weather map that gave him the idea. (06:25)

Race and Reclaiming a Refuge

View the page for this story

In 1979, a group of unarmed black protesters briefly occupied Georgia’s Harris Neck National Wildlife Refuge in an effort to rebuild a community displaced decades earlier. Reporter Joseph Rose of the Oregonian magazine tells host Steve Curwood how that occupation contrasts with the recent standoff involving white ranchers in Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. (08:35)

BirdNote: The Feathers that Carry Water

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

The Feathers that Carry Water: Living in water-poor environments is a challenge for many species, but as BirdNote’s Mary McCann reports, male Sandgrouse use an ingenious method and his feathers to carry water for miles back to the nest. (01:50)

Killing Wolves in British Columbia

View the page for this story

Forest caribou populations in British Columbia are struggling, and in an effort to give them a boost the government has decided to start culling the species' primary predator—wolves. It's a controversial move, but wildlife biologist Chris Johnson tells host Steve Curwood that it's going to such drastic measures in the short term to keep these iconic species around. (06:30)

What a Wolf's Howl Says

/ Jennifer JerrettView the page for this story

When a wolf howls in Yellowstone’s snowy landscape, a howling chorus responds. But in the spring, the wolves grow quieter as they raise pups. Now researchers understand how wolf calls change with the seasons, and hope to answer the tougher question of what the howls actually mean. The park’s reporter-in-residence, Jennifer Jerrett, has the story. (02:50)

Wolves Have "Howling Dialects"

View the page for this story

Members of the wolf family howl, some like coyotes in shorter varied bursts, others like the European grey wolf in a long tonal call. Now, University of Cambridge researchers have found that different types of howls and their preference for use are identifiable as a dialects. Study author Arik Kershenbaum speaks with host Steve Curwood about the finding and how this could be used for management of wolves. (07:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Steve Kretzmann, Chris Johnson, Alexander MacDonald, Joseph Rose, Arik Kershenbaum

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann, Jennifer Jerrett

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Renewable energy could slash gobal warming emissions though wind and solar energy are seen as intermittent. But the weather map and new transmission lines could meet that concern.

MACDONALD: Weather is big. You know, you look in the weather map of the United States, you see a giant high in the west, a low that’s windy in the east, so you can kind of deduce that if you can share the power over a large area then it’s not intermittent.

CURWOOD: And it could cut power sector emissions 80 percent. Also activists sue to stop British Columbia shooting wolves from helicopters. But some scientists say it’s necessary to protect vanishing caribou herds.

JOHNSON: I think in the short term we need to look at predator removal as a valid option; the data support this. This will at least keep caribou around.

CURWOOD: Wolves and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Obama Calls For New Oil Tax

An oil tax is aimed at greening the transportation sector. (Photo: raymondclarkeimages, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

[THEME RETURN]

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. President Obama is now looking for a $10 fee on every barrel of oil. The fee would tack about 20 cents on every gallon of gasoline and pump about $32 billion a year into the federal treasury. The President wants that money to finance “21st century clean transportation,” as part of his $4.1 trillion budget plan. Election year politics mean his budget proposal and its oil fee probably won’t get very far in the Republican-led Congress. Capitol Hill Democrats are also calling for a measure that would halt more fossil fuel development in federal territory, and set in stone the President’s recent executive order blocking new coal leases on public lands. Joining us from Washington to discuss these proposals is Steve Kretzmann, Executive Director and Founder of Oil Change International.

KRETZMANN: Well, so the idea is that they would impose a $10-a-barrel tax on oil production and apparently on oil consumption, exempting that oil that is produced for export, but it would generate quite a bit of money over time. I think they’re talking in excess of $300 billion on an annual basis.

CURWOOD: Alright, so let me make sure I understand this, Steve. It's $10 a barrel fee on production so when it comes out of ground, a fee gets levied, and then there'll be another $10 a barrel fee based on what consumers take? I just need to be clear on this.

KRETZMANN: Yeah, to be quite honest the administration hasn't been clear about this. They have said exactly that, that it's on production and consumption, but they haven't been clear about the mechanics about how that would work. You know, I think the reality of this proposal is, it's kind of a messaging proposal in a way to start a conversation with the nation about what our energy future should be about, right? This thing is dead on arrival in Congress, as we heard from I don't know how many Congressional leaders the moment that it was released, but the point the administration is making here is an important one which is that our continuing addiction to oil costs us all a lot of money.

Obama’s proposed tax would only impact production and consumption of oil, not natural gas or coal. (Photo: Ken Hodge, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

The International Monetary Fund recently did a study where they looked at how much fossil fuel addiction is costing us on an annual basis and they put that number at - get ready for this - $5.3 trillion every year. And what they're doing there is they're adding up the subsidies that governments directly provide as well as the costs from climate change and local pollution and all those sorts of things, so that's a huge number. In the US if you break down the IMF numbers, the cost is about $400 billion annually for oil alone and so that actually squares pretty well with the administration's proposal. And so it's clear to me that they're trying to start a conversation about how do we deal with these costs moving forward.

CURWOOD: So what you're saying is this $32 billion is against how much in terms of subsidies that the federal government is giving to the oil business right now?

KRETZMANN: About $17 billion in direct subsidies that the government is giving the oil industry. That’s our tax dollars that are being used to support the industry on an annual basis.

CURWOOD: So the overall increase actually would be half that.

KRETZMANN: Right. It would be about half that, but what that's beginning to do is add in the costs of adapting to climate change, the costs of pollution to communities, the costs to all of our health that fossil fuels are continuing to impose. I think it's a completely reasonable number when you look at that.

CURWOOD: Steve, what would be the potential consequences of taxing oil while not taxing other carbon polluting resources? I'm thinking of coal and natural gas.

KRETZMANN: Well, it's aimed at the transport system, right, it's aimed at an electrifying transport system, so you're going to discourage oil use which doesn't have that much to do with electricity in the first place but has everything to do with transportation, right? And so to the extent that the administration is trying to move us to a 21st century energy transport system that is reliant on electricity, it makes some sense to single out oil first and foremost as something that really needs to be costed appropriately.

CURWOOD: So how hopeful are you that this could be the start of a real bipartisan conversation on building a transportation future, the White House putting down a marker, let's put a fee on a barrel of oil.

President Obama’s recent budget proposal calls for a $10 “fee” on every barrel of oil. This would be used to fund “clean transportation” initiatives. (Photo: ProgressOhio, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

KRETZMANN: I'm hopeful that more and more people in Washington are talking about it. I'm not hopeful that this budget cycle in the next year is going to be something that moves more money into clean transportation at this point, but you know to the extent that it helps to frame conversations in the election this year, to the extent that it helps to point the direction for where we need to go in the future and hopefully lays down, you know, it's standing at home plate and pointing to the fences and saying we're going there, right? Ten to 15 years from now we'll look back and we'll say, “that was a really important thing because that showed us the vision for how we want to make our energy system in the future.”

CURWOOD: So just recently I believe more than a dozen - perhaps as many as 17 - members of the House have introduced what the called the Keep it in the Ground Act. Talk to me about that briefly and where you think it's going?

KRETZMANN: This is a really important piece of legislation because climate policy for very long time has been all about how we reduce demand and how we reduce consumption and how we bring it into line with the climate imperatives. Now we're seeing an increasing number of people look at the supply side. When we know from the carbon math, from the best climate science that we have, that we already have 80 percent more fossil fuel reserves than we can burn and in a climate safe world, we know that the idea that taking more out of the ground, that finding more through new exploration is completely inconsistent with climate science and is in fact climate denial. We're just not going to be able to go on producing this oil and gas, because once you do open up new areas it becomes very challenging to shut them down. Because the way the oil industry works is to spend a lot of money up front to try to open up a new area, and then they pay back their investment over time. So if we continue to facilitate them opening up new areas we are unlocking more carbon moving forward.

CURWOOD: And this bill would prevent the United States government leasing any more land or undersea territory for the extension of fossil fuels.

KRETZMANN: That's right.

CURWOOD: Not much chance of getting it through this Congress I would say.

KRETZMANN: Not much, but again it's a marker bill.

Steve Kretzmann is the Founder of Oil Change International. (Photo: Oil Change International)

CURWOOD: Well, interesting enough, the president has already put out a temporary hold on coal leases to begin from public lands. This is getting some traction I would say.

KRETZMANN: Absolutely, it's getting some traction, because I think it's very clear from the climate movement's perspective that this is something that has to happen moving forward, right, the fact that we have all those democratic presidential candidates endorsing this point of view, the fact that we have actual bills in Congress that would support this and move this. It's not going to happen in this Congress as we talked about before, but it's likely to happen soon and the writing is very much on the wall for the industry.

CURWOOD: Steve Kretzmann is the Executive Director and founder of Oil Change International. Thanks for taking the time today, Steve.

KRETZMANN: Thanks, Steve.

Related links:

- White House fact sheet on the oil tax

- Keep It in the Ground Act of 2015

- Oil Change International

Beyond the Headlines

A natural gas storage facility of the Southern California Gas Company in Aliso Canyon. (Photo: Scott L., Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time to go beyond the headlines now. Peter Dykstra of the DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, EHN.org has been checking it all out and joins us from Conyers, Georgia. What’s noteworthy today, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. The Aliso Canyon natural gas storage facility in Southern California has been much in the news due to that massive methane leak that spewed from October until early February when it was temporarily plugged. As the methane clears and residents head back to the Porter Ranch community, there’s more news.

CURWOOD: Not more bad news, I hope?

DYKSTRA: Well, reporters from the Los Angeles News Group, that’s a chain of dailies in Southern California and inewsource, which is a journalism nonprofit, analyzed EPA data from 2014 — that’s the year before the leak — and Aliso Canyon was emitting enough CO2 and methane to equal a year’s worth of output from 43,000 cars.

CURWOOD: So we’re talking about CO2 as well as methane here?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, the methane mostly comes from leaks from the facility; the carbon dioxide is emitted from the machinery used to pump the natural gas underground in the first place. There are only two other US natural gas storage facilities that leaked more greenhouse gas in 2014: one in Texas and one in Mississippi.

CURWOOD: And, as I understand it, there are some 400 underground gas storage facilities in the US. Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, last month we talked about citizen opposition to the growing North Carolina solar industry. The residents’ concerns, among other things, were that a new solar farm might suck up all the sunlight from a nearby town.

Some North Carolina lawmakers choose to focus on the future environmental costs of solar panels. North Carolina has four commercial nuclear reactors, 42 sites on Superfund, 50 coal ash ponds roughly 3,800 industrial hogwaste storage lagoons. (Photo: Stefano Paltera/U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Wow, when the martians land, I guess, huh?

DYKSTRA: Right so we’re going to go back to North Carolina, but this time, it’s the state legislature who a few years ago famously outlawed the use of sea level rise data in coastal planning.

CURWOOD: So what are they doing this time?

DYKSTRA: Well here you go, let me set the scenario. North Carolina has four commercial nuclear reactors that store their nuclear waste on-site, 42 sites on the Superfund toxic clean-up list, 50 coal ash ponds and roughly 3,800 industrial hogwaste storage lagoons, so the legislature and the state Environment Agency have decided to focus on the menace of solar panels. The rapid growth of the solar industry in North Carolina has them concerned about disposing of the panels in the future.

CURWOOD: The menace of solar panels — how menacing are they?

DYKSTRA: Well, you know, there are some legitimate concerns that without thorough recycling processes, solar panel disposal might be an issue, but probably not for 25 years, which is the typical lifespan of a panel. There aren’t enough panels now reaching retirement age to create an economically viable recycling industry just yet but photovoltaic panels typically contain some metals, potential pollutants but they are also potential recycling bonanzas. The state environment commissioner also expressed concerns that a hurricane or a tornado could make a mess of a big solar farm.

CURWOOD: Hmm, I seem to recall that already happened with some of those big hogwaste lagoons?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, more than once and speaking of North Carolina hogwaste, I’ve got a little hog history for you.

CURWOOD: Do I have to hold my nose?

DYKSTRA: Only if you’re downwind. I’m talking about Boss Hog.

CURWOOD: You’re talking about that county commissioner from the Dukes of Hazzard show?

DYKSTRA: No, we’re still in North Carolina. That show was shot right here in Conyers, Georgia and thereabouts. Boss Hog was also the name of a great environmental reporting project by the Raleigh News and Observer, that launched 21 years ago this week. The series covered the political clout of the hog industry in North Carolina, the risks to waterways and groundwater from those thousands of hogwaste lagoons, and the human costs in health and the smell.

In February of 1995, the Raleigh News And Observer published a series of investigative stories about the hog Industry in North Carolina and how waste storage posed many sanitary hazards. (Photo: Dana McMahan, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: And what’s changed in the last 21 years?

DYKSTRA: Well the Boss Hog series helped call attention to the problem, but the industry has grown and there’s been little change in the way the waste is handled. 7 million hogs in 1995, there are 10 million today in North Carolina — that’s more hogs than people. The average size of a hog has grown a bit too. The hog industry in North Carolina employs thousands — it’s economically crucial to the eastern half of the state, so many people literally hold their noses and get to work. The Boss Hog series won a Pulitzer Prize for reporters Pat Stith, Melanie Sill, and Joby Warrick.

CURWOOD: At least they brought some bacon home to the Raleigh News and Observer.

DYKSTRA: That’s right, a little pork barrel politics story.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News that’s EHN.org and the dailyclimate.org — thanks Peter! We’ll talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve thanks a lot, talk to you again soon.

CURWOOD: There's more on these stories at our website, LOE.org. We’d also like clarify our story last week about Hampshire College going 100 percent solar. The College contacted us to say they thought we had misrepresented their environmental initiatives by not mentioning their new campus center, which they say is constructed to the greenest building standards in the world. Also, they say using 100 percent solar energy to power the school will save $340,000 a year.

Related links:

- Aliso Canyon was major pollution source before massive leak

- Solar backers try to allay NC lawmakers' fears about panel removal

- Some Environmental Costs Of Solar Panels

- Boss Hogg Investigative Project wins Pulitzer

- Rural Poor Pay For World’s Cheap Bacon

[MUSIC: Sultans Of String, “Palmas Sinfonia” on Symphony! MCK/Red River]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...a weather eye to converting the power grid to 80 percent renewables without needing more storage. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Sultans Of String, “Palmas Sinfonia” on Symphony! MCK/Red River]

Converting the Economy to Renewable Energy Without Big Batteries

High-voltage direct current transmission lines could help transfer electricity over long distances much more efficiently and make renewable energy more viable. (Photo: Chris Hunkeler, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. For folks who worry that the intermittent nature of wind and sun mean renewable energy is not ready for prime time, a team of leading weathermen has a surprising answer. They say within 15 years the US could slash 80 percent of global warming emissions from the power sector, meet increased demand and keep consumer costs low without batteries by building an efficient electric grid. That’s according to a study called NEWS, the National Electricity with Weather System. It uses weather forecasting to model renewable energy supply and demand. Meteorologist Alexander MacDonald recently retired as Director of NOAA’s Earth Systems Research Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado. He led the team and took a break from shoveling his snowy driveway to explain the concept, and what inspired him.

MACDONALD: I heard people talking about, well, renewable energy doesn't work because it's intermittent, and I remember saying, well, it's intermittent if you just have it over really small area, but weather is big. You know, you look at a weather map, you see a giant high in the west of the United States, a low that's in the east, so you can kind of deduce that if you can share the power over a large area then it's not intermittent. So I wanted to find out if that was true.

CURWOOD: So essentially the wind is always blowing some place in America. What did you set out to find out in your study?

MACDONALD: I started on this six years ago and I decided with my team that we would do a cost minimization. In other words we would say, well, we will actually allow wind and solar and other sources like natural gas and even nuclear and coal to be part of the study and we would minimize the total cost of the system with the requirement that it supplied electric energy to 250 places over the United States every hour for a year. So it was kind of a complicated -- what's called an optimization that we used.

CURWOOD: So what did you find?

The wind isn’t always blowing at the San Gorgonio Wind Park in southern California, but with an interconnected grid that spans the continental U.S., energy from breezy weather elsewhere could make up for a lull in the wind here. (Photo: Alex Ferguson, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

MACDONALD: Well, what we found is that the larger the geographic area, the more effective wind and solar can complete. And it's for the exact reason that you think. If it's a really small area, if the wind stops in part of the area it stops over most of the area. Just take the state of Kansas, if it's not blowing on one side of Kansas, it's probably not blowing on the other. However, if you take the whole 48 states you can always find places where is pretty windy, so that's essentially what the study showed us.

CURWOOD: The point that you make in your paper this really intriguing is that we can use all this renewable energy without storage and for the same amount of money. How is that possible?

MACDONALD: Well, that's a really interesting question. We really did put in every possible type of electric energy system. So we had storage as one of the things we could use. We had transmission where we can move power over a small area or we could move it over the whole country, and we basically said to this optimization, “you choose what is the best option.” What it chose was at the prices that we expect that it chooses transmitting the power across the country as the least expensive way to use the wind and solar. Now if we have a breakthrough in the future in the cost of electric storage that would just make the system that much better.

CURWOOD: Except I gather there's a bit of rub. It's not so easy these days in America to send energy from say the East Coast to the West Coast.

MACDONALD: No, you’d have to build transmission lines. This type of transmission is called a high voltage direct current transmission and can get huge amounts of electric energy a long ways, but still really within the cost envelope for the studies that we looked at.

CURWOOD: So what you're saying is if we build massive transmission lines, we could still keep the cost at pretty much what it is today and be pretty much all renewable?

MACDONALD: That's exactly what the study showed. It showed that we could have costs of electricity about what it is today, but it would reduce carbon dioxide up to 80 percent, so it's I think a pretty important result from the study.

CURWOOD: So, part of this is that you can get to 80 percent reduction of carbon emissions, but can't get to 100 without becoming very expensive, I gather.

MACDONALD: Our kind of study was saying what can we do quite rapidly, and it's like many economic things if you get to 80 percent, the price is the same as today, but if say we've got to get all the way to 100, we might double or triple the cost and we don't believe that, you know, most people could live with a double or triple cost of electric energy.

CURWOOD: OK, Sandy, I'm sitting down. How much would all of this cost?

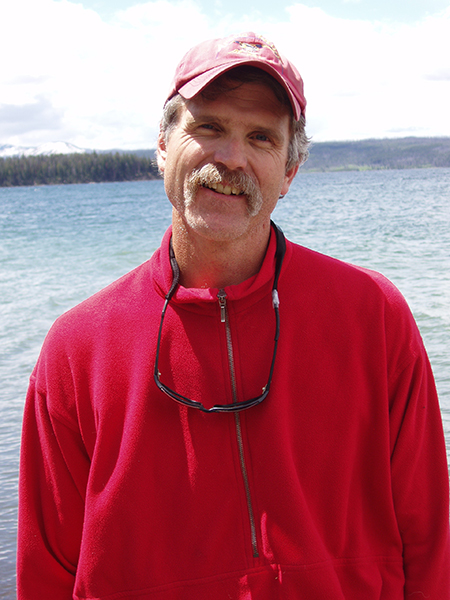

Dr. Alexander MacDonald, recently retired director of NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory, co-lead author of renewable energy study published recently in Nature Climate Change. (Photo: courtesy of NOAA)

MACDONALD: So in the pricing that we used which was from the Energy Information Agency, the whole sort of super grid for transmission was about $200 billion, and that's against the total cost of upgrading the entire system, including the wind and solar power and so on, of $2.6 trillion. It turns out that we're going to pay, and these are figures by 2030, close to $2 trillion just to replace aging coal plants and other things, so the transmission is a relatively cheap part of moving to a wind, solar and natural gas system which is the one that gives us the 80 percent reduction in CO2.

CURWOOD: Sandy, how realistic is it to build these transmission lines, these direct current transmission lines? There's a lot of opposition when someone tries to put a pipeline or a highway or anything, you know, not in my backyard.

MACDONALD: Yes, and I think people are going to have to weigh like everything else. If we want to preserve the future this shows policymakers an opportunity to do it, and it's not for free. You might have to have overland lines, you might have to pay extra money, say, add a penny per kilowatt hour to your electric bill to have underground lines, but it gives us an option to have low carbon and low-cost energy economy, and we think that's a pretty valuable possibility.

CURWOOD: Alexander McDonald recently retired as director of NOAA's Earth systems laboratory and is lead author of the team that created NEWS, the National Electricity with Weather System. Thanks a lot, Sandy.

MACDONALD: Thank you very much, Steve.

Related links:

- “Rapid, affordable energy transformation possible”

- Study in Nature Climate Change: “Future cost-competitive electricity systems and their impact on U.S. CO2 emissions”

- Direct Current Versus Alternating Current

- About Alexander MacDonald

[MUSIC: Herbie Mann et al, “Sunny” on A Man and a Woman by Bobby Hebb, Atlantic]

Race and Reclaiming a Refuge

Harris Neck National Wildlife Refuge in 2012 (Photo: Becky Skiba/USFWS, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It took the best part of six weeks for the occupation of the Malheur wildlife refuge in Oregon by armed ranchers to come to an end. But in these times that have demonstrated that law enforcement all too often uses excessive and deadly force against unarmed African Americans, some have asked whether the authorities would have been as patient with black, rather than white occupiers. As it turns out, there’s a precedent where the occupiers were black and unarmed. In an article for the Oregonian, reporter Joseph Rose tells the story of the 1979 occupation by black protesters at the Harris Neck National Wildlife Refuge in Georgia. Joe Rose joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

ROSE: Thank you. It's a pleasure.

CURWOOD: Please give us the back story of how a black community formed there in Harris Neck a number of years back. What caused them to lose the land?

ROSE: Well, after the Civil War, the white plantation owner in this predominantly overwhelmingly white county in Georgia on the coast decided to deed all the land to former slaves, and there's this rich direction going back through this cultural unique group of African Americans called the Gullah. They raised their families there. They set up, for all intents and purposes, what was a city with a vibrant economy based on fishing and on farming. There was some manufacturing there. There was even some cattle ranchers in the area. It was a very vibrant community.

CURWOOD: And what happened then?

ROSE: In World War II, the U.S. Army came in and took over the land. It was essentially a case where you have eminent domain that the army said that they had the right to do during wartime, paid the African-Americans who lived there just pennies per acre, and they were essentially forced out. There was a great controversy, because there was a lot of uninhabited land in this county in Georgia where there were no communities, no structures, that could have easily have been used by the military for air strips, which is what they wanted for training and patrols, but they were owned by white landowners who kind of wink, wink, nodded and said, “why don't you look over at Harris Neck” and that's exactly what US government did.

The former Harris Neck Army Airfield, pictured from the air in 2006. (Photo: United States Geological Survey, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: So World War II is over. What happened to the land? I gather people didn't get it back. Why not?

ROSE: Well, the US government gave it to the county. The black settlers said that they were promised by the US government that once it wasn't needed for military exercises after the war that it would be given back to the African American community that once existed there, and the landowners who had a legitimate claim to it. Instead the military gave it back to the county; the county couldn't keep up with the land, and they weren't getting a tax revenue off of it, so they agreed to give it back to the US government, which turned it into a wildlife refuge.

CURWOOD: So, I guess by 1979, folks were were pretty fed up with this and they decided to occupy it. What did the protesters hope to accomplish?

ROSE: Well, they didn't go in armed with weapons like the Bundys did here in Oregon. What they did was they went in armed, if you will, with building materials. They wanted to once again start building a community. This was not only a symbolic gesture, but it was also a stance where they felt that they had a legitimate right to this, whereas the Bundys, you know, no one thinks that they had a right to any of that land. In this case, in this community, what they wanted to do was obviously make a stance and stay there as long as they could, nonviolent protest. In the end, though, this was during the Carter Administration, the FBI went in within three days and forcefully removed all of the campers and arrested them.

CURWOOD: So who did the FBI arrest and drag out of there?

ROSE: Well, in the end there was an ultimatum given within a couple of days that if you don't leave you will be arrested. Most of the people did leave. They did not want to be arrested. They felt that they had made their point. But there were four people left over in their tents, and within less than 24 hours they were forcibly removed from those tents, and they were physically dragged into paddy wagons, they were arrested and they were sentenced to jail for trespassing.

CURWOOD: How long did they stay in jail?

ROSE: I think some of the sentences were for up to a month.

CURWOOD: And how many were black?

ROSE: All four were.

CURWOOD: So, how did the rhetoric that the media used during this protest, this 1979 protest, differ from what we've seen during the wildlife refuge occupation in Oregon?

ROSE: It seemed to be that the occupiers in Oregon, while they were roundly ridiculed and criticized, the media has taken a stance where they're trying to be as impartial as possible. If you look at the headlines back in 1979 during the Harris Neck occupation, the headlines were almost insulting. They were called “black squatters,” in fact, that they were “ejected”. There was almost like a police blotter tone to it, that these were criminals.

CURWOOD: By the way what is the status of the case that the families used to live at Harris Neck have brought into the courts? They must have tried to sue at some point, I'm sure.

ROSE: It's still active, on appeal. Several times they've tried to sue and the federal government has rejected their claims.

CURWOOD: And what's the basis of the government saying that these people aren't entitled to the land they gave up for the war effort?

Wood stork in flight at Harris Neck National Wildlife Refuge (Photo: Huhnra, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

ROSE: The government's stance is that there was never any written or legal documentation that stated that the government would give it back once it entered into a type of foreclosure by the government, for military operations.

CURWOOD: What does race have to do this story?

ROSE: You have a predominantly African American community, a very unique African-American community, that existed in a county that is predominantly white, a history of Ku Klux Klan activity and a feeling that the government ignored taking white land over taking land that was already being used, like I said, for a very vibrant seaside community that was African American. So they felt from the very beginning, there were backroom deals done that singled out a black community for takeover by the US government, and that race played a role from the origins of this.

CURWOOD: What kind of local support does the Harris Neck community have for getting their land back?

ROSE: Unfortunately, very little. Most of the support has come from historians and researchers outside of Georgia, within African American organizations who feel this was a great injustice, and within the community, like I said, this was, this is in a county that’s still predominantly white. The descendants and the survivors of Harris Neck, you know, they're on their own, unfortunately.

CURWOOD: Joe, what brought this story your attention?

ROSE: Well, I've been one of the reporters covering the occupation of the wildlife refuge here in Oregon and trying to put it into historical context. And I did some research looking at any other refuge occupations like this, and ironically there was, as I found out, there was this occupation of a wildlife refuge that involved unarmed black occupiers that was dealt with swiftly by the federal government. Of course the thing to remember is that this was before the Branch Davidians, and the federal government and the FBI especially has changed their tactics on how they approach these type of standoffs since then. So it could be argued, while some people see this as strictly as a different of races and the races involved with the occupiers, it could be argued that it was just as much about how the federal government has changed its tactics when dealing with occupiers on federal land.

CURWOOD: Joe, remind us of what happened in the Branch Davidian situation.

ROSE: Well, the Branch Davidian situation was a group of armed Seventh-day Adventists who had a compound, they were in a standoff because of weapons issues and there was also federal charges against David Koresh, who was the head of the Branch Davidians, and he refused to leave the compound. So after several days the ATF and the FBI raided the compound. It ended in bloodshed with several children and occupiers killed.

Joseph Rose is a reporter with the Oregonian. (Photo: courtesy of Joseph Rose)

CURWOOD: But that was not on federal land. They just simply were holed up on there on their own land.

ROSE: Was not. No, it involved federal charges.

CURWOOD: What do you hear in terms of the Harris Neck community saying, hey, maybe we should go back and reoccupy this?

ROSE: I haven't heard anything like that. Again, whatever they do probably would not have anything to do with an armed occupation. They've been adamant from the very beginning that if they are to get their land back that it needs to be through peaceful resistance and protest.

CURWOOD: Joseph Rose is a reporter for the Oregonian. Joseph, thanks for taking the time with me today.

ROSE: You bet. My pleasure.

Related links:

- Joseph Rose’s article: “Oregon standoff: Feds forcibly removed black occupiers from wildlife refuge in 1979”

- About the Gullah Geechee culture

- Harris Neck Wildlife Refuge

- 1979 coverage, “Harris Neck Battles U.S. Government”

- Harris Neck descendants request lease of refuge land

- About Joseph Rose

BirdNote: The Feathers that Carry Water

Burchell's Sandgrouse (Photo: Ian White, Flickr CC)

[BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: Water is vital for all life – but it’s not always available where you need it. And as Mary McCann explains in today’s BirdNote®, sometimes it’s the male of the species that takes on responsibility for the supply.

BirdNote®

Sandgrouse - Desert Watercarriers

[Lichtenstein’s Sandgrouse (3869) 01:07 and following]

Sandgrouse – pointy-tailed relatives of pigeons – live in some of the most parched environments on earth. To satisfy the thirst of newly hatched chicks, male sandgrouse bring water back to the nest by carrying it in their feathers. It sounds incredible, and for decades, scientists thought it was just a myth. But it’s not. In the cool of the desert morning, the male flies up to twenty miles to a shallow water hole, then wades in up to his belly.

[Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse (3868) 01:10 and following]

Burchell's Sandgrouse takes flight, carrying water in his feathers. (Photo: Ian White, Flickr CC)

The water is collected by “rocking.” The bird shifts its body side to side and repeatedly shakes the belly feathers in the water; fill-up can take as long as fifteen minutes. Thanks to coiled hairlike extensions on the feathers of the underparts, a sandgrouse can soak up and transport 25 milliliters of liquid. That’s close to two tablespoons.

[Lichtenstein’s Sandgrouse (3869) 02:29 and following]

Once the male has flown back across the desert with his life-giving cargo, the sandgrouse chicks crowd around him and use their bills like tiny squeegees, “milking” their father’s belly feathers for water they so desperately need.

I’m Mary McCann.

[Lichtenstein’s Sandgrouse (3869) 02:29 and following]

Written by Rick Wright

Sandgrouse chicks “milk” the adult male’s feathers for water. (Photo: Steve Garvie, Flickr CC)

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse [3868] by Myles E.W North; Lichtenstein’s Sandgrouse [3869] by Myles E.W. North.

BirdNote's theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org February 2016 Narrator: Mary McCann

http://birdnote.org/show/sandgrouse-desert-water-carriers

CURWOOD: You’ll find pictures of these ingenious watercarriers at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- More about the Sandgrouse and its ability to carry water

- Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse Pterocles exustus

- Burchell's Sandgrouse Pterocles burchelli

[MUSIC: Ladysmith Black Mambazo, “Full Rain Full Rain,” on Shaka Zulu, Warner Bros. Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the call of the wild, and the seemingly never ending battle between humans and wolves. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provide building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Peter Ostroushko With Dean Magraw, “Three Brazilian Melodies” on Duo from the playing of Jacob de Bandolim, Red House Records]

Killing Wolves in British Columbia

Caribou on the run (Photo: Libby Ehlers/UNBC)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

CURWOOD: They’re eerie, scary, full of mystery and an iconic soundtrack of wild places, including Yellowstone National Park, where these Rocky Mountain wolves were recorded. Yellowstone’s reporter in residence, Jennifer Jerrett, sent them to us.

[MORE HOWLING WOLVES]

CURWOOD: Wolves have cause to howl so mournfully, because many humans have it in for them. Ranchers in the western US say that since wolves have been restored to much of their ancestral range, there are too many of them and they kill livestock. And in the Rocky Mountains of Canada, marksmen shoot them from helicopters as part of a five-year wildlife management program in British Columbia to protect dwindling woodland caribou populations. Environmental groups are challenging the government in court, arguing that the science does not justify the killings. But caribou conservation expert Chris Johnson from Northern British Columbia University says there are few options to help caribou populations pushed to the edge of extinction.

Moose cornered by a pack of wolves, central British Columbia, Canada. (Photo: Dale Seip)

JOHNSON: Well, the primary predator of caribou is wolves, and so the data suggests there's a surely high mortality rate for adults but also young newborn caribou, and so the simplest and probably the most effective lever in trying to increase caribou populations is to reduce mortality, and the primary source of mortality is wolves.

CURWOOD: What's the state of the caribou?

JOHNSON: Caribou across Canada are a species at risk, so that's a formal definition that recognizes that in many places they receive legal conservation protections. And the caribou in this part of the province where the wolf cull’s happening, they’re currently listed as a threatened species. They were recently reassessed and there’s a recommendation to the Federal Minister of Environment that they be uplisted to endangered. So here in the central portion of the province, one evolutionarily distinct group of caribou, there's only around 270 of them left in British Columbia, maybe another 100, 150 in Alberta, so we’re talking less than 500 animals spread over a very large area.

CURWOOD: To what extent are the wolves to blame for the small numbers of Caribou — or maybe something else is going on here?

Females from the Quintette caribou herd in British Columbia (Photo: Libby Ehlers/UNBC)

JOHNSON: Well, you ask a very good question with a somewhat complex answer. The situation we have with wolves and caribou at the moment isn't a direct relationship between wolf numbers and caribou numbers. What we have on that land base as well as a number of other ungulate species, and in British Columbia and the central part of the province, it's mostly moose. So we have lots of moose, which are supporting fairly large and well dispersed wolf populations. So the wolves are really dependent on the moose, and then when a wolf finds a caribou it's also likely to kill that caribou. The caribou are incidental kills, they’re sort of just the cherry on the top of the sundae for the wolves. They don't necessarily go looking for caribou during most of the year, but if they happen to come across a caribou they’re certainly going to hunt them, it’s a very natural response for a wolf.

CURWOOD: What other pressures are on the caribou? Habitat? Forage? What's going on for them?

JOHNSON: Yeah, so there's definitely issues with this species, with woodland caribou around the impacts of industrial development. So forestry is a big player in British Columbia, in the central eastern part of the province where we have only around 270 caribou, there’s also a fairly extensive oil and gas development and coal mining as well. And so those activities do a couple of things, they force caribou into smaller areas, they reduce the amount of habitat for caribou, if we’re thinking about forage. Probably most importantly, they create what we call early successional plant types, which moose and other deer like, and there you go; now you’ve got more moose and you’ve got more caribou. So I guess it is not a simple relationship. We’ve got at least three species involved, and we have greatly modified the land and so all the things have come together to conspire against caribou.

CURWOOD: Now, some conservationists are challenging the BC government in court over this wolf cull. Why do you think they are challenging this cull?

Moose, the primary prey of wolves in central British Columbia, take advantage of early seral plant communities created by landscape disturbance associated with forestry, natural gas development and other forms of landscape change. (Photo: Chris Johnson)

JOHNSON: I think there're a lot of reasons to oppose the wolf cull. There’s been a lot of talk right across Canada about the ethics of controlling or killing one species to potentially save another. And some people feel that as conservation biologists it should be a sort of “do no harm” principle, that even if we’ve got an imperiled species like woodland caribou that doesn't justify killing wolves. So there’s a lot of emotion, there's a lot ethical and moral objections to this to this program. I certainly understand that. There's also some people that feel that maybe the government isn't upholding their end of the multipart deal and when government was looking for support for this wolf cull, they also pitched the idea of aggressive habitat conservation and potentially even restoration. And so some people are looking at the government and asking, “Where’s the habitat restoration, where’s the habitat conservation? We agreed that a wolf cull might be effective over the short-term if you promised to address some of these long-term habitat issues.” And so there's a couple different perspectives on why there may be limited support for a wolf cull.

Chris Johnson is a Professor of Ecosystem and Science Management Program at the University of Northern British Columbia. (Photo: University of Northern British Columbia)

CURWOOD: So there are, of course, a number of management options here. What do you think is the best way for us to use our resources?

JOHNSON: I feel again, thinking this from a scientific perspective that we need a multi-pronged approach. I think we need to look at the levels of industrial developments that are happening in some of these caribou range and really ask ourselves, “Do we want to conserve caribou and what are we willing to spend to do that?” And that's going to result in maybe less natural gas exploration and development, maybe fewer coal mines. Maybe fewer cut blocks. But I think in the short term we need to look at predator removal and predator control as a valid option. The data support this; this will at least keep caribou around and although it's, no one would probably argue this is a long-term strategy, it’s very expensive and it’s not palatable to the majority of the public, it does have some short-term wins relative to maintaining caribou on these landscapes.

CURWOOD: Chris Johnson is a professor in ecosystem science and management at the University north of British Columbia. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

JOHNSON: Thanks for your interest in this issue.

Related links:

- Study: Managing wolves (Canis lupus) to recover threatened woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in Alberta

- Management: Airlifting Pregnant Caribou Away From Wolves

- B.C. govt hunters keep this wolf alive so they can kill others

- Management Plan for the Grey Wolf (Canis lupus) in British Columbia

- Mountain Caribou Recovery Plan

- Chris Johnson teaches at the University of Northern British Columbia

What a Wolf's Howl Says

A wolf from Yellowstone's Druid Pack mid-howl (Photo: NPS Photo)

CURWOOD: Though wolves are under fire in British Columbia, the packs in national parks like Yellowstone give wildlife experts the chance to study many aspects of their behavior. And as Jennifer Jerrett explained, when it comes to howling wolves, scientists say there’s a time for every purpose under heaven.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

JERRETT: Researchers in the park have recently discovered that there is a seasonal cycle to those howls.

[HOWLING FADES]

JERRETT: Biologist Doug Smith is the project leader for all of the wolf research that takes place in Yellowstone National Park. He says that if you’re a wolf in Yellowstone, you still howl in the spring…

SMITH: … but you howl less, you only howl when you need to and you’re only howling to your packmates. As the summer grows old you start howling more and more, and so now you start howling to your neighbors, your enemies, and it increases through the fall and winter. That’s the seasonal cycle.

Wolf pups in spring (Photo: NPS Photo)

JERRETT: The seasonal cycle peaks in February, which tracks right along with the breeding season in Yellowstone. And there’s a lot of howling back and forth between neighboring or rival wolf packs.

SMITH: Wolves are ferociously territorial, and so they howl to others to say ‘Hey I’m here, stay out.’

JERRETT: But in the spring, when wolves start establishing den sites to raise pups, everything changes.

You never forget your first wolf in the wild. (Photo: NPS Photo)

SMITH: So what appears to be happening during the denning season is that howling for territorial purposes goes away. You stop communicating to your neighbors. So what we’ve noticed what doesn’t go away is howling to your packmates, to your family members.

JERRETT: So while there’s less howling overall in the spring and summer, the call-and-response that does go on is almost entirely within pack. Doug has been studying wolves for 35 years. He explains what might be happening.

SMITH: In the winter the pack’s all together and they travel widely, they go everywhere. When they have those pups, wham! An anchor gets thrown in, they become your ball and chain. And wolves need to carry on their business, but they also need to care for their pups. So they leave the pups at the den and they split up. Well, that presents a problem of how you coordinate activities, how do you communicate, how do you find each other. Well, you howl.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

Doug Smith is a wolf biologist and the project leader for wolf restoration program in Yellowstone National Park. (Photo: NPS Photo)

SMITH: So what’s so important about that story is that was a previously unknown story. Now enter Yellowstone.

JERRETT: The only way that the research team working in Yellowstone was able to tease apart this seasonality – more howling that tends to be territorial in the fall and winter, less howling that’s more family-focused during spring & summer -- is because when it comes to wolf research, Yellowstone’s landscape is unique. There’s a lot of open country in the park. So you can see the wolves… see what they do when they howl. And this is what provides the context for understanding howling.

CURWOOD: That’s Jennifer Jerrett from Yellowstone National Park, where she’s reporter in residence.

Related links:

- More on the wolves in Yellowstone via National Park Services

- Montana State University Library's Acoustic Atlas

- Yellowstone Association

- The Yellowstone Park Foundation

Wolves Have "Howling Dialects"

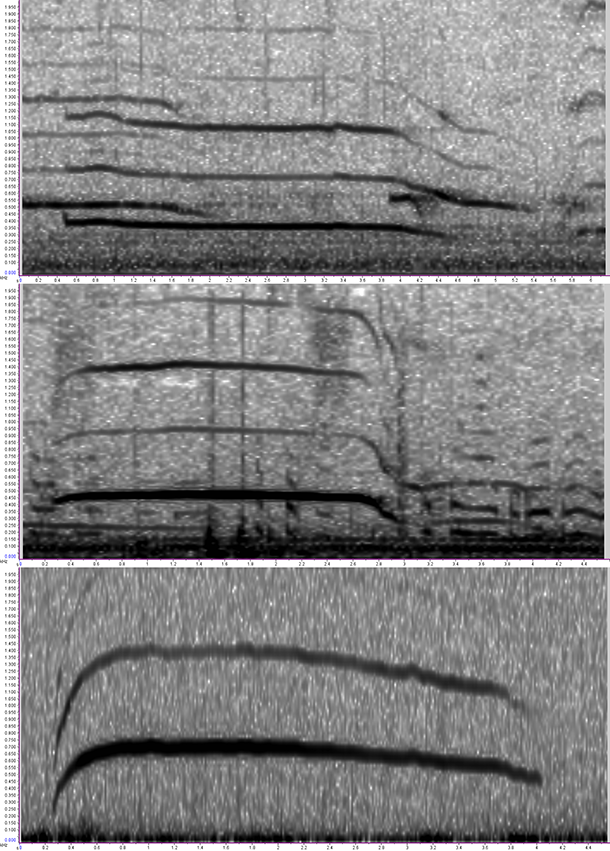

Different canid populations and subspecies use howling as a means of communication. Each group has their own preference for use of vocalizations, and Kershenbaum’s group found that these fit into one of 21 “dialects.” (Photo: Arik Kershenbaum)

CURWOOD: Now it’s not only the seasons that seem to affect the howls of wolves and their kin; apparently all the members of the dog family, the canis clan, have what we might call different “accents”. This means, for example, that Russian forest wolves don’t sound like North American timber wolves, and African wild dogs sound very little like Australian dingos. A team at Cambridge University’s Zoology Department has been analyzing the sound spectrum of howls from various members of the dog family, to identify their unique signatures. Arik Kershenbaum is lead author of their study published in Behavioural Processes, and we called him up to find out more about it. Welcome to Living on Earth!

KERSHENBAUM: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So you've been looking into wolf talk; what did you set out to find when you began this investigation?

KERSHENBAUM: So we’ve known for a while that you can detect differences in wolf howls by ear, but we did want to get away from this subjective interpretation, because of course we don't know whether the cues that we are picking up on as humans are the same cues that are being detected and interpreted by the animals themselves. So we went out to measure similarity and difference quantitively and objectively without the interference of our human perception.

From top to bottom: spectrograms of a Tibetan grey wolf howl, a Mackenzie Valley grey wolf howl and a European grey wolf howl. (Photo: Arik Kershenbaum)

CURWOOD: So what were you looking for in this research and what did you find?

KERSHENBAUM: We were looking to see whether different wolf subspecies in different wolf populations have howling behavior that is distinctly different from each other — so, whether you can tell the difference between a North American wolf and a European wolf merely by listening to their howls. We collected several thousand howls from wolf populations around the world, mostly captive animals from zoos but also some animals in the wild. We collected recordings of different subspecies of gray wolves…

[GRAY WOLVES HOWLING]

KERSHENBAUM: … red wolves, coyotes, jackals, dingoes…

[DINGOES HOWLING]

KERSHENBAUM: … and we also scanned YouTube videos of domestic dogs howling as well. So we assembled these all into a database and then put them through mathematical algorithms that extracted the details on the howls themselves, and then formed a comparison between them to measure their similarities and differences.

Northwestern wolves howling at the Wolf Conservation Trust, UK. (Photo: Beth Smith)

CURWOOD: Now this is really getting interesting, because I'm imagining that you're able to sort out a bit of geography and subspecies this way.

KERSHENBAUM: So what we found was, first of all, that the computer came back and told us that that there were twenty-one distinct types of howls. And this was across the full range of all of the wolf subspecies and other species and coyotes and jackals and dogs as well.

CURWOOD: Arik, play a couple of these wolf howls for me and tell me how you were able to quantify the differences.

Many of the howl recordings came from captive populations of wolves, domestic dogs and other canids. (Photo: Becky Barrett)

KERSHENBAUM: All right‚ well this is the howl of a Mackenzie Valley wolf, or a northwestern wolf. So this is a species that occupies the Northwest in the United States and Canada and the Rocky Mountains…

[MACKENZIE VALLEY WOLF HOWLING]

KERSHENBAUM: And to compare that this is the howl of a red wolf, which is a much smaller species from the Southeastern United States…

[RED WOLF HOWLING]

KERSHENBAUM: Well, the first thing that stands out is that the larger wolves have a much flatter, much

KERSHENBAUM: Well, the first thing that stands out is that the larger wolves have a much flatter, much more constant pitch, lower pitch. Whereas the smaller animal, the red wolf, howls in a much more warbling way, going up and down in pitch, rising and falling.

CURWOOD: Well, we can hear a difference -- but how do you quantify the difference?

Video of howling wolves at night, taken at the Howler's Inn B&B in Bozeman, Montana, using the Yukon Ranger Pro 5x42 Digital Night Vision Monocular. (Arik Kershenbaum)

KERSHENBAUM: So the way that we quantified it was to extract the frequencies of the howls as the howl progresses -- whether the frequency rises, falls, stays constant. And then we could compare every set of howls that we recorded, and that essentially gives a number to how different two frequency modulated turns are. And we then passed that to another algorithm which clusters these howls into groups that are similar to each other and different from every other howl.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the differences -- what, in your view, makes up a dialect?

KERSHENBAUM: So once we had established the twenty-one different howl types, what we did is we looked at the way those howl types were used by different populations. So some species and subspecies would make a lot of use of certain howl types and would neglect others. In addition, some species make wide use of all of the different howl types and are very varied in their repertoire. And in that sense they represent, if you like, a fingerprint for each population, for each subspecies.

CURWOOD: So, without ever seeing these animals, one could identify them.

KERSHENBAUM: Yes, given enough recordings of the animals in a particular area, you would be able to identify which subspecies they are most similar to, just from the way that they use the different howl types.

CURWOOD: What about hybrids? To what extent can you use your technique to identify distinct populations or subspecies or incidents of interbreeding?

Setting up recorders in Yellowstone to triangulate wolf howls. (Photo: Arik Kershenbaum)

KERSHENBAUM: So the entire genus of canis is a bit of a genetic mismatch; most species can interbreed with each other, so it's really more one large species than a collection of separate species. Now, when we look at reintroduction programs for the red wolf, which was driven extinct in the wild in the middle of the last century in the southeastern United States. And they found that one of the major problems with this reintroduction was that the wolves were hybridizing with coyotes that had come in after the red wolf became extinct and essentially taken over their niche. When we looked at the howling behavior of red wolves --

[RED WOLF HOWLING]

KERSHENBAUM: ... and the howling behavior of coyotes —

[COYOTE HOWLING]

KERSHENBAUM: … and also the howling behavior of the eastern timber wolf, which is a smaller subspecies of gray wolf that occupies the northeastern United States —

[EASTERN TIMBER WOLF HOWLING]

KERSHENBAUM: We found that the howl type fingerprint of the red wolf was intermediate between that of the northeastern wolf and the coyote. So there is some indication that the red wolf could have a genetic past that places it between those two species. And it could also mean that we could use some of these behavioral indicators to measure the degree of mixing of populations.

Kershenbaum found that larger wolves tend to use a low tonal howl with little variation in frequency, whereas smaller canids like the coyote use a highly-varied howls. (Photo: courtesy of Arik Kershenbaum)

CURWOOD: So you’ve established that there are these wolf dialects. Where do you go from here?

KERSHENBAUM: Well, if we can use these kinds of techniques to identify different howls in different behavioral contexts, then we may be able to use the howling to develop techniques for reducing conflict between wild predators and humans, by playing back the appropriate howls. But in this case it would be extremely important to make sure that you play back a howl that says, don’t come near here, we’re a strong and aggressive pack, and not a howl that says, come over here, we’ve found some interesting food and we’re going to eat it.

CURWOOD: Arik Kershenbaum is a research fellow at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology and lead author of the study, “Disentangling canid howls across multiple species and subspecies,” recently published in Behavioural Processes. Arik, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

KERSHENBAUM: My pleasure.

Related links:

- Wolf species have ‘howling dialects’, release from the University of Cambridge

- More on Dr Arik Kershenbaum and his work

- Canid howls: a window to cognition and cooperation

- Study: “Disentangling canid howls across multiple species and subspecies: Structure in a complex communication channel”

- Winter Wolf Song, an audio postcard from Yellowstone

[MUSIC: Adrian Legg, “St. Mary’s” (Nashville tuning) on Wine, Women, and Waltz, Relativity Records]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth: trade, travel and global warming raise the risk of diseases like the Zika virus for humans and also help spread deadly fungal diseases that threaten wildlife.

KOLBERT: We are bringing together these evolutionary lineages that have been separated for tens of millions of years, and we are getting a lot of nasty surprises.

CURWOOD: Bats, amphibians and snakes at risk. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Adrian Legg, “St. Mary’s” (Nashville tuning) on Wine, Women, and Waltz, Relativity Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Peter Boucher, Jaime Kaiser, John Duff, Amber Rodriguez and Jennifer Marquis. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE dot org. And like us, please, on our Facebook page. It’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. And Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. And from Solar city, America’s solar power provider. Solar city is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth