February 26, 2016

Air Date: February 26, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

El Niño Brings Hunger Emergency

View the page for this story

Drought associated with El Niño is hammering subsistence farmers in Asia, Latin America and much of Africa, and creating a hunger emergency for 60 million people. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Nahuel Arenas of Oxfam America about the unfolding humanitarian crisis. (07:30)

Drought and African Wildlife

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

This year's El Niño that’s causing extreme droughts in parts of the world is causing skyrocketing food prices in southern Africa. But nature has also used drought through the ages to adjust the balances among prey and predators. Bobby Bascomb reports from Johannesburg, South Africa. . (05:00)

U.S. Climate-Changing Emissions Drastically Underestimated

View the page for this story

Measuring the emissions of the powerful climate-changing gas methane emissions is difficult, as it escapes from wetlands and landfills as well as from oil and gas drilling and pipelines around the world. Now, a team of scientists using satellite data with ground observations has found a better way to calculate its presence. Daniel Jacob, Harvard professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Environmental Engineering, tells host Steve Curwood their recent study suggests much more methane is escaping than estimates had calculated, and the US could be responsible for up to 60 percent of the extra. (06:50)

Proposed Rules to Curb Methane Leaks

View the page for this story

Federal and state agencies have proposed rules to limit methane leaks in oil and gas infrastructure. Vermont Law School professor Pat Parenteau and host Steve Curwood discuss the importance of tackling the methane leak problem and the regulatory proposals for doing so. (08:10)

BirdNote: Early Bird Gets the Nesting Site

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Competition for nesting sites is fierce as migrating birds return north for the summer months, but as BirdNote’s Michael Stein reports, clever bluebirds and the tree swallows beat the rush—staking their claim before others have a chance. (02:00)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about unexpected health effects linked to breathing Beijing’s dirty air and how exposure to a toxin in the sea ruined this year’s Dungeness crab season. It also poisoned California’s seabirds years ago, inspiring a famous Alfred Hitchcock film. Traveling back in environmental politics, they consider how ignorance related to environmental contamination of food contributed to the Salem witchhunt. (03:45)

Fungal Diseases Surge, Threatening Species Around the World

View the page for this story

From the chytrid fungus in frogs to white-nose syndrome in bats, fungal diseases have been wreaking havoc on many animal species around the world. Writer Elizabeth Kolbert authored an article about the global surge in these diseases in Yale’s magazine E-360. She discusses the causes and possible actions to protect animals in the future with host Steve Curwood. (09:10)

Microbes Fight Fungal Disease in Frogs

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Fighting the fungal diseases that have killed millions of frogs and other amphibians is a top priority, and new research suggests natural soil bacteria might provide protection. UMass Boston biology professor Doug Woodhams tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer how they work. (02:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Nahuel Arenas, Daniel Jacob, Pat Parenteau, Elizabeth Kolbert, Doug Woodhams

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Michael Stein, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Hunger is stalking parts of Asia, Central America and Africa as a powerful El Niño boosted by climate change parches subsistence farmers. And some city dwellers are also in trouble.

ARENAS: Malawi, Zimbabwe, and South Africa, the harvests have been really, really hard hit, prices of foods are increasing by 50 to 100 percent, so it makes it really difficult for poor families to access food.

CURWOOD: But when it comes to Africa’s wildlife, the drought paints a mixed picture.

SMIT: So, some species will be disadvantaged for example hippo, buffalo, warthog, and water buck. And then there are other species that are actually favored by drought conditions. Think about your predators and your scavengers, because there’s so much more food available.

CURWOOD: And it could improve the health of some species. That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

[THEME RETURN]

El Niño Brings Hunger Emergency

An Ethiopian child waits to collect water from an Oxfam tank. (Photo: Abbie Trayler-Smith/Oxfam)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The worst drought in decades is hitting much of Africa, Central America and Asia, thanks to one of the strongest El Niños ever recorded, and that means more than 60 million people are facing severe hunger.

And while El Niño has kept rain away from areas such as the Horn of Africa that are regularly short of water, it has pummeled other regions with storms, including the typhoon that recently ravaged Fiji.

Scientists now know the regions where the arrival of El Niño means drought won’t be far behind, and for months international humanitarian groups have been raising the alarm about the crisis. But there is still a shortfall in cash to deal with it. Nahuel Arenas, Director of the Humanitarian Response Department of Oxfam America, joins us. Welcome to Living on Earth, Nahuel.

ARENAS: Thank you.

Fatuma Hersi with two of her children. She has lost all but 7 of her 300 sheep and goats since the drought began. (Photo: Abiy Getahun/Oxfam)

CURWOOD: So, what are we seeing in terms of drought across Africa right now?

ARENAS: So, what we are observing is really a concerning situation. It is a combination of drought exacerbated by the El Niño phenomenon which really creates a huge humanitarian crisis.

CURWOOD: Now, you say El Niño is involved. What does El Niño do for these droughts?

ARENAS: So, El Niño is a natural phenomenon, it happens every seven or eight years. What happens is that temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean become warmer than normal. That releases heat into the atmosphere and produces changes in rain patterns, in wind patterns, and also in ocean currents. So, in terms of its consequences, it has exacerbated weather events like droughts or floods. So, in places like Ethiopia, we are observing one of the hardest droughts in the last 50 years. This is really made worse by this El Niño phenomenon.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, though, with the link between El Niño and these droughts, there's an ability to predict that there's going to be trouble down the road. What happened this time in terms of predicting the drought in Ethiopia, and how has it helped handling the humanitarian crisis?

Gile Gedid, an Ethiopian herdsman, has lost 27 cattle since the drought began. (Photo: Abiy Getahun/Oxfam)

ARENAS: Yes, the capacity of governments and also humanitarian agencies to relieve these kinds of situations has really improved over the years, however, Ethiopia is still a country with 80 percent of its population depending on agriculture, and most of that is really dominated by small scale farming. Which means that farming is the means of survival for many people, and that leaves them vulnerable to climatic events like this one.

CURWOOD: How bad is it in Ethiopia right now?

ARENAS: Well, according to the Ethiopian government who has really been leading the response to this crisis, over 10 million people are in need of humanitarian aid, and this is in addition to the almost eight million that are already being supported by the government's existing emergency system.

CURWOOD: Ten million people need aid? How soon?

ARENAS: Well, right now, if we are not able to act now, these numbers will increase over the next months. This is a trend we are observing also in other places in eastern and Horn of Africa as well in southern Africa, where overall in the world according to the UN agencies, over 60 million people will be affected by El Niño.

CURWOOD: So, Ethiopia's a hotspot. Where else? Southern Africa?

ARENAS: Well, places like Malawi, Zimbabwe, South Africa — harvests have been really, really hard hit. Prices of food are increasing by 50 to 100 percent. So it makes it really difficult for poor families to access food.

CURWOOD: And you also say there's also trouble in Latin America.

Amina Hassen and Shukri Ige try to get water from a well dug by villagers. (Photo: Abiy Getahun/Oxfam)

ARENAS: Yes, we are talking about Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua mostly. This drought in Central America we have been working, helping families to access food and water for the last 12 months, but the next months are really the ones that will make people suffer the most.

CURWOOD: So, how soon are we going to see pictures of starving babies, the horrible face of hunger that we saw a generation ago when things were really bad in the Horn of Africa.

ARENAS: Well, malnutrition is already a problem, particularly in places like Ethiopia. It's already a reality. The Ethiopian government has been very strong in leading the response. They have put around $200 million dollars to respond to this emergency, but the estimation is that to properly respond to the needs, we need $1.4 billion in Ethiopia only. So, we are hoping the international community is able to support countries like Ethiopia.

CURWOOD: To what extent is the United States government stepping up here to help?

ARENAS: The US is a leader in the world. We are hoping that they can do more and support governments around the world dealing with this crisis, but also humanitarian agencies. Also, for example, our funding tariff to assist 800,000 people is $25 million dollars, of which we have only been able to raise near $8 million, so I think we really need to be conscious of the current challenge and to step up and to double our efforts to respond appropriately before it is too late.

CURWOOD: So, how do you deal with this, Nahuel? What are some of the best practices that you folks in the humanitarian aid business employ when you run into situations like this?

An Ethiopian woman with her goats (Photo: Abiy Getahun/Oxfam)

ARENAS: The humanitarian system really is overstretched. As you know, the crisis in Syria, the refugee crisis, right now we have a historic record in the number of displaced people in the world, over 60 million people. What we are doing in places like Ethiopia is really ensuring that the poorest families have access to safe water, access to food, keeping their livestock alive. Let's take an example of a poor pastoralist family in Ethiopia. They may survive a couple of hundred of sheep or goats and some camels, and what we are seeing on the ground right now is that these same families may possess now 10 goats or sheep and one camel. So, it's really hard for these poor families to recover. So, these are the kind of families that we are trying to help.

CURWOOD: So, what's your outlook on this with global warming? Some would say we're going to see a lot more of this.

ARENAS: Yes, research suggests that climate change can be doubling the quantity of super El Niños like this one. So, although climate change does not create this situation, the El Niño situation, it does reinforce the patterns which is a deadly combination. Both El Niño reinforces climate change and climate change reinforces the El Niño. So, we might be observing a new normal here, and that's what the challenge ahead is.

CURWOOD: So, as someone who works for an international aid organization, where does climate disruption rank in terms of the humanitarian threats that people are facing around the world right now?

Nahuel Arenas (Photo: Oxfam America)

ARENAS: Well, it's something that we need to think of not only in the short term in terms of humanitarian response, we need to be looking at this in the long run. And that means different strategies to help communities with climate change adaption, so it's imperative that we tackle this now. What we've seen in Paris in terms of commitments to climate action, it's great, it's really a landmark step. Over 190 countries committed to climate action, but what we need is further commitments to ensure there is sufficient climate adaptation finance for vulnerable communities to adapt to increasingly unpredictable and extreme weather events like this one.

CURWOOD: Nahuel Arenas is Director of the Humanitarian Response Department of Oxfam America. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

ARENAS: Thanks, Steve.

Related links:

- Oxfam report on the Ethiopian drought

- Impacts of El Niño around the world

- Help Oxfam provide aide to people coping with El Niño

- World Food Program on Ethiopian Drought

Drought and African Wildlife

Waterholes are drying up, and cattle are finding brittle yellow stalks where green grass once was. So far, tens of thousands of cattle have died due to the drought. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: The deep drought is painful for people across the whole of southern Africa. But as reporter Bobby Bascomb found, the picture is more complex for the continent’s iconic wildlife.

[SFX AMBIANCE SOUNDS, MUSIC]

BASCOMB: It’s a scorching hot day at the Fourways Farmer’s market in Johannesburg, South Africa. Market goers take refuge in the shade of big leafy trees and sip on icy drinks from mason jars.

Local farmer Clint Halkett-Siddel stands behind his stall of organic vegetables. He says locals should be able to count on rain this afternoon to cool things off.

HALKETT-SIDDEL: In Johannesburg we’re used to it being four o’clock everyday of the week we get an afternoon thunderstorm. That has changed dramatically over the years.

BASCOMB: This year South Africa is experiencing its worst drought since 1910, when they began keeping records. Halkett-Siddel says the lack of rain is making it difficult for him to farm, and what food he can grow will be more expensive for consumers.

HELKETT-SKIDDEL: We are lucky to have a nice aqueduct under our property and we use borehole water for our irrigation, but it obviously means that we’ve got more labor intensive production happening. Pushes up the cost of the produce that we are able to produce because we have to employ staff to water the grounds every day, instead of relying on the natural rain.

South Africa normally exports corn, but drought conditions mean that they’ll need to import it from as far away as South America. Corn supplies are even worse in Zimbabwe and Mozambique. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: The drought has been particularly severe in the agricultural heartland of the country. Normally South Africa exports corn, but this year they will have to import it, from as far away as South America. And currency devaluation is making imports particularly expensive. Already the staple food here, a cornmeal called pap, has gone up in price by roughly 50 percent.

Other countries in the region are even worse off. In Mozambique the price of corn has nearly doubled and in Zimbabwe, where crops are failing and tens of thousands of cattle have already died, the government has declared a state of disaster.

Roughly 14 million people in Southern Africa don’t have reliable access to affordable food – they’re what David Orr of the World Food Program in Johannesburg calls food insecure.

In Fourways Farmer’s market in Johannesburg, South Africa, farmer Clint Halkett-Siddel sells organic vegetables. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

ORR: Vulnerable people are experiencing issues with being able to feed themselves and their families. We hear of families who are reducing the number of meals, cutting meals, often selling their prized livestock to earn some money.

BASCOMB: Orr expects even more people will be struggling with food security in Zimbabwe once the full effects of the drought are felt in April – the month when the year’s crops are normally harvested.

ORR: They’re talking about the harvest in at least one province, three-quarters of the crop, being a write off.

BASCOMB: A drought like this that’s so devastating for farmers and people struggling to feed themselves also affects wildlife. Waterholes are drying up, and instead of succulent green grass animals are finding brittle yellow stalks. But the drought can actually be good for wildlife in the long run. That’s according to Isak Smit, a scientist with the South African National Park Service.

SMIT: We’ve got sympathy with agriculture and local communities. A lot of human beings’ welfare and livelihoods are severely affected by these droughts. However, in these natural systems like national parks, we realize that droughts are actually a natural and important event that’s been happening over millennia.

Some predators like lions can benefit from drought conditions, which cause many prey species to die, providing a banquet of sorts for larger animals. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Smit says a drought is nature’s way of resetting the ecosystem. And for wildlife, there will be winners and losers.

SMIT: So, some species will be disadvantaged — for example, hippo, buffalo, warthog, and water buck. And then there are other species that are actually favored by drought conditions. Think about your predators and scavengers, because there’s so much more food available, and the animal’s conditions are lowered so it’s easier to catch prey. One should also see there are some really fat lions walking around and that the wild dogs are having big litter sizes.

BASCOMB: But of course, the ecosystem can only support a limited number of predators, so those many wild dogs and fat lions will ultimately face more competition to catch a reduced number of prey animals. But Smit says increased mortality is actually good for the species.

SMIT: During drought some of the weaker and the diseased animals are the first to die. So, the animals that are the fittest and have got the best genetic material actually then form the basis of your population after the drought.

BASCOMB: So survival of the fittest individuals now will make the species as a whole more equipped to survive drought again in the future.

Smit says some animals have already died from lack of food and water, and rivers and watering holes that are low now will be even more depleted in July and August when the normal dry season arrives.

So, the worst of this drought is still to come, for wildlife and people alike.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Related links:

- The state of corn shortages in Zimbabwe

- South Africa to ease some GM crop rules to avert food crisis

- Grain Millers Oppose South African Corn-Import Tariff Review

- Worst South Africa Drought in Memory Cuts 2016 Corn Crop 25%

- David Orr of the World Food Programme

- Dr Izak PJ Smit of South African National Parks

[MUSIC: David Jacobs-Strain, “Earthquake,” Ocean or a Teardrop (Northern Blues 2004)]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...the US is now responsible for a massive increase in emissions of the powerful global warming gas methane – without strong plans to control it. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Jacobs-Strain, “Earthquake,” Ocean or a Teardrop (Northern Blues 2004)]

U.S. Climate-Changing Emissions Drastically Underestimated

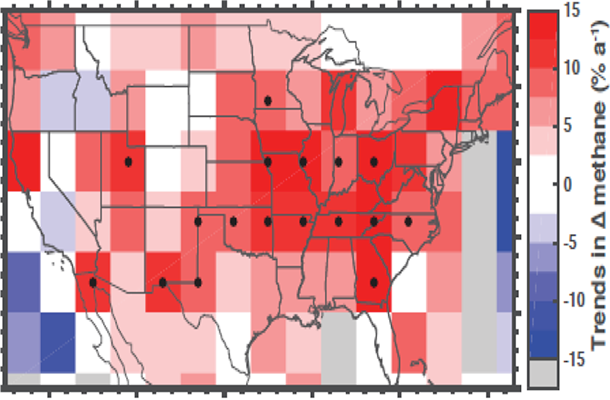

Rising methane emissions across midwestern US (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Jacob)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. When the global warming gas methane is first emitted, it’s roughly 90 times as powerful as carbon dioxide, and there’s more than twice as much of it in the atmosphere now than there was before the start of the industrial revolution.

There are many sources – wetlands, agriculture, landfills, and of course, oil and gas production — and the recent massive natural gas leak near Los Angeles drew attention to the environmental impact of methane.

Now a new study from Harvard University, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, documents a spike in global methane emissions to levels far higher than previous federal estimates.

The study claims the United States may be to blame for up to 60 percent of the global growth in human-caused methane emissions. For an explanation we turn to lead author Daniel Jacob, professor of atmospheric chemistry and environmental engineering at Harvard University.

JACOB: So, we tried to look from the satellite data at fingerprints of where methane could be increasing, and we found the large increase over the past decade of emissions of methane in the US, of about 30 percent — which, if you consider what it would contribute to the global increase of methane, would amount to 30 to 60 percent of the global rise in methane.

CURWOOD: You say "fingerprint of methane". What are you talking about?

JACOB: We’re trying to figure out where methane is being emitted, and where the increase in methane is coming from. And so the way you figure this out is by looking at the areas around the Earth where methane is increasing faster than average. And this is what led us to the US.

CURWOOD: So, methane molecules don't have any particular identity. They're all carbon atoms surrounded by four hydrogens. There's not a particular kind of methane that you're able to identify with a fingerprint methane.

JACOB: You're absolutely right. Methane is methane. Now, if you look at methane isotopes you could try to figure out where methane is coming from, but we cannot observe those from satellite.

The researchers envision a methane monitoring system for North America, which integrates satellite data with surface and aircraft observations. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Jacob)

CURWOOD: Now, some people listening to us would say: ‘But professor, the spike you've identified seems to have started from the time of shale oil and natural gas, the boom beginning in the US. Come on, there's got to be a connection to this.’ How do you respond?

JACOB: I respond that there might be, but our data doesn't provide a smoking gun for figuring out where the methane is coming from. It's just showing that there's been a large increase in the methane emissions in the United States. The tempting hypothesis is indeed that it's due to oil and gas, but more work is needed to figure out where that source might be and also what processes are involved. I mean, oil and gas is a very complicated source. You have emissions associated exploration, with production, with processing, transmission, compression, distribution. And at all these steps in the supply chain you could have emissions, so it's going be difficult to tease out if it is coming from oil and gas, which we really cannot tell.

CURWOOD: Now, how does this compared to other measurements that have been made?

JACOB: We examine a bunch of studies that have been done over the past decade of looking at methane in the atmosphere over the United States, and comparing to emission inventories. And what these studies repeatedly show is that our current national emission inventory for methane that’s produced by the Environmental Protection Agency is too low.

CURWOOD: And of course, one major source of this discrepancy might well be that as things warm, wetlands are releasing more and more methane and the government doesn't go out and ask a wetland how much methane it’s releasing.

JACOB: No, so the government is not looking at emissions from wetlands right now, except manmade wetlands such as rice patties. But we can use satellite observations, again, to see how much methane is coming out of wetlands and the trends associated with that. I think you bring up a good point that the atmosphere doesn't lie. When we see methane in the atmosphere, we know it came out of something. Whereas the emission inventory from EPA doesn't really know about methane in the atmosphere, it just knows about the different activities that are emitting methane. So there really needs to be a partnership between EPA and the atmospheric scientists to resolve the difference that we're presently seeing.

CURWOOD: Tell me, what's the difference between your data and the current federal data?

Daniel Jacob is the Vasco McCoy Family Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Environmental Engineering at Harvard University (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Jacob)

JACOB: The EPA gathers information on all of the sources that it thinks are emitting methane, and it's really pretty good at this. So, it knows where all the landfills are, where all the major livestock operations are, the different components of oil and gas supply system, the leakage from coal mines and so on. The inventory that comes out of this is what we call a bottom-up inventory, in that it looks at the individual processes that are emitting methane and tries to estimate how much methane is associated with these different processes with the individual sources. What we can do from the atmosphere side is what we call top-down constraints, in that the atmosphere tells us how much methane there is. And it gives us a rough idea of where it's coming from, but it cannot as easily pinpoint the methane to individual sources.

CURWOOD: And to what extent could satellite monitoring be a way to look at what other countries around the world are doing in terms of methane?

JACOB: I think it's a silver bullet. We've been hampered until now because the satellite observations that we have are fairly sparse. In other words, from satellite we can see globally where methane is coming from, but the picture is a little blurry. But later this year in October, the Dutch are going to be launching a new satellite instrument. And that's going to provide us with a much finer picture of methane emissions, and so we'll be able to observe methane every day around the world with a resolution with about five miles. So this is going to revolutionize our ability to observe methane from space.

CURWOOD: So according to your research we've been underestimating methane emissions for long time. How much might we been underestimating global warming gases from the US in general, do you think?

JACOB: Yeah, this appears to be an issue for the past decade or so that the emissions are being underestimated, and that doesn't come just from us. There are numerous studies that are showing this, so the view is that the methane emissions of the United States are underestimated by 30 to 50 percent. And I would say that's pretty much a consensus view from atmospheric scientists that have been looking at methane emissions from the US.

CURWOOD: Daniel Jacob is a Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Environmental Engineering at Harvard University. Professor, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

JACOB: It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Study: A large increase in US methane emissions over the past decade inferred from satellite data and surface observations

- About Daniel Jacob and Harvard’s Atmospheric Chemistry Modeling Group

- Draft U.S. Greenhouse Gas Inventory Report: 1990-2014

- Reconciling divergent estimates of oil and gas methane emissions

Proposed Rules to Curb Methane Leaks

Drill pads dot a rural landscape with rich oil and gas deposits. EPA’s proposed methane rules would only apply to new or “significantly modified” oil and gas facilities. (Photo: Simon Fraser University--University Communications, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Measuring methane emissions in the US can’t slow global warming by itself. But regulations to rein in methane are still mostly in the proposal stages at both the state and federal levels. And for insight as to how they might work we called up Professor Pat Parenteau, at Vermont Law School. Pat, welcome back to Living on Earth.

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Steve.

CURWOOD: First of all, how has the EPA proposed to regulate methane? They proposed some new rules a couple of months ago.

PARENTEAU: They have. This is the first time the EPA has proposed rules to regulate methane from oil and gas exploration and production, and what they're saying is that we're only going to apply this rule to new wells and their supporting facilities, or existing wells that undergo what's called substantial modification. That's a very good first step. But as many have pointed out, it's far from adequate because the estimates are that fully 90 percent of the emissions coming from the oil and gas production process are coming from, of course, the existing infrastructure which is very substantial across the country.

Geology of conventional and unconventional oil and gas extraction. Many old oil wells have been converted for gas storage, like the ones in Aliso Canyon. (Photo: US Energy Information Administration)

CURWOOD: Now, there have been some studies looking at methane emissions in the US. We recently talked to some folks at Harvard that found maybe 30 to 60 percent more coming from the US than previously thought. And there was another study that found that in a limited area, Barnett Shale where there's a lot of tracking going on in Texas, that half of the emissions were coming from just two percent of the facilities there. What does that tell you in terms of regulatory effectiveness?

PARENTEAU: Well, it certainly tells me there are holes in the regulatory system, and a lot of these wells are very old. In some cases they're 50 years old, and of course the specifications for how they were installed and how they’ve been maintained are subject to a lot of question. And because EPA has not asserted direct control over these wells and their supporting facilities, a lot of this leakage and emissions have gone unmonitored and undetected. Unless, of course, a state or local agency might be doing it, but apparently in the Barnett shale they haven't been doing a very good job.

CURWOOD: And I guess it doesn't take much of a leak to make a huge mess, as we saw in California with Aliso Canyon, huge amounts, and it sounds like in the Barnett Shale, just a couple places are dumping enormous amounts of methane into the atmosphere, but the EPA rules wouldn't cover any of that.

PARENTEAU: No, the EPA rules would not. The Aliso Canyon is remarkable. It is the biggest methane leak ever, known about, anyway. Five months it took to close the facilities in the canyon that were leaking, so it certainly underscores the need to address these existing facilities.

CURWOOD: Now, how is the industry responding to these proposed rules by the EPA which only affect, as you say, new facilities, or greatly revised facilities?

PARENTEAU: The industry's taking the position that no new rules are necessary, that they're duplicative of existing rules, that EPA should basically butt out and leave it to the states. And the curious thing is that the studies show that, of course, methane is basically gas, it's a valuable commodity. And the Environmental Defense Fund did a recent study saying that the cost would be more than offset by the value of the gas that could be captured. That, of course, depends on the price of gas on the global market and lots of other considerations.

The BLM’s proposed methane rules seek to limit gas flaring, venting and leaking on public lands. (Photo: Tim Hurst, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, what about the proposed rules from the Bureau of Land Management? That's the federal agency that handles extraction from public lands.

PARENTEAU: Yeah, that's another big piece of the puzzle. There are over 100,000 oil and gas wells on public lands in the west managed by the Bureau of Land Management. And, again, under Obama's comprehensive climate action plan, the BLM proposed to control what are called flaring and venting of these gas wells, which results in something on the order of 300 billion cubic yards of gas a year.

CURWOOD: Whew.

PARENTEAU: And the industry sued in Wyoming, and they found a friendly judge who's issued an injunction. And the really astounding thing is the judge said that the BLM doesn't have the authority to regulate fracking on public lands. And the judge said the reason is because back in the George W. Bush administration, you will remember perhaps the famous Cheney task force. This task force came up with a series of exemptions for the oil and gas industry, one of which was an exemption from the Safe Drinking Water Act for production wells, including wells they claim on public lands. A lot of the people looking at this, including yours truly, believe that that decision is wrong and that eventually it will be overturned, but for now BLM has been ordered not to proceed with the rule.

Map of all federally owned land in the United States. The Bureau of Land Management is shown in gold. (Photo: National Atlas of the United States, public domain)

CURWOOD: So, let's see. In terms of regulating methane, we're kind of batting zero here. The EPA would only look at new things. The BLM has been hit with a court order stopping it. I understand California has proposed some methane rules. How do those look?

PARENTEAU: The California rules are very aggressive. Obviously the Aliso Canyon has lit a fire - that's a bad pun - under the state, and they have come up with rules that would much more strictly monitor and regulate existing storage facilities like Aliso Canyon, as well as pipelines and transmission facilities. Of course, it will take time to stand up that regulatory program, but at least California now has a good set of rules on the books, Colorado has some good rules on the books. But, you know, the system is nationwide and the problem is huge.

CURWOOD: Now, natural gas is often touted as an energy source that emits a lot less carbon dioxide than other sources such as coal, but when you factor in these weeks in the short-term effects of methane from oil gas drilling, is it indeed a net positive or is it a net negative in terms of helping to deal with the threat of climate change?

PARENTEAU: The scientists suggest that unless you can keep the leakage rate from the natural gas system somewhere between one to three percent, that you're going to probably offset the reduction in carbon dioxide from the combustion of the gas at the power plant. Of course, EPA relies exclusively on industry estimates for the rate of leakage, and as these independent studies have come out, it appears that those leakage rates are much, much higher. Some of the studies, for one example, the Uintah basin in Utah, indicated that the leakage rate from that fracking operation was 13 percent, and then there was another study in California showing 17 percent leakage rate. So we're way above the safe levels that the scientists are talking about at least in those places where we've looked and, of course, the problem is we haven't looked everywhere. Unless this methane emission problem can be brought under really strict control, it looks like gas is not going to be the way forward.

Compared with coal-fired power plants, natural gas plants produce less carbon dioxide in the process of generating electricity. But because of methane leaks in the gas transportation system, natural gas may do more harm to the climate. (Photo: Duke Energy, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: This is not very good news. It sounds like we're really rapidly increasing the rate of climate disruption for something that we're not paying much attention to. Tell me something that's good about this.

PARENTEAU: Well, the good news is that what's required to reduce these emissions is not rocket science. In fact, it's plugging leaks, and in fact it's putting people to work repairing these pipelines, replacing the older ones, installing monitoring equipment, installing what's called green completion facilities that actually capture the methane gas and use it productively, and it's now just simply a matter of doing it. And if industry is willing to do it voluntarily, as everybody hopes, that would be fine. But having regulations that say you really do have to do this would certainly move us forward much faster.

CURWOOD: So, like so many things, I guess this is, the fate of these rules and carbon regulation and a whole bunch of things, may hinge on what happens in November and who wins the White House.

PARENTEAU: I think that's absolutely right, Steve, the stakes probably this year for environmental law, for the future of climate change regulation, the future of the Supreme Court, all of it seems to be front and center in this election cycle.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is a Professor of Environmental Law at Vermont Law School. Thanks so much, Pat, for taking time with us today.

PARENTEAU: You're very welcome, Steve.

Related links:

- Pat Parenteau’s “Status of Methane Regulation in the United States”

- The EPA’s proposed methane rules

- The BLM’s proposed methane rules

- California’s New Methane Rules Would Be the Nation’s Strongest

- EPA Draft Says Oil & Gas Methane Emissions Are 27 Percent Higher than Earlier Estimates

- Our previous coverage of EPA’s methane rules

- About Pat Parenteau

BirdNote: Early Bird Gets the Nesting Site

Tree Swallow nestbox. (Photo: Mike Hamilton)

[MUSIC - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: The days are getting longer, and that brings thoughts of spring and its many pleasures. And principal among those are returning birds, as Michael Stein explains in today’s BirdNote.

BirdNote®

Nest Cavities – Book Early

[Rapid series of male Tree Swallow’s song-like notes]

A flash of glittering dark blue cuts through the gray of late February, as a male Tree Swallow glides low over a cattail marsh. The Tree Swallow’s liquid notes hint at spring’s approach.

[Repeat rapid series of male Tree Swallow’s song-like notes]

Where a broad, green pasture meets the forest edge, there is a second, even brighter flash of blue. A male bluebird alights on a fence post, the intense blue of its back glints in the welcome sunlight of late winter.

[A bit of Eastern Bluebird song]

Western Bluebird male protects his nesting site from competitors like the starlings and house sparrows. (Photo: Tom Grey©)

Tree Swallows and all three North American bluebird species are among the earliest northbound migrants to arrive, heralding spring a month before the equinox. Both species will nest only in cavities, such as old woodpecker holes or man-made nest-boxes. The supply of such specialized nest sites is limited. Competition is intense. By arriving so early, Tree Swallows and bluebirds improve their chances of finding unoccupied cavities – and they may fiercely guard a nest site until April, before actually nesting.

Both species benefit greatly from nest-box programs. But it is crucial to put up only nest-boxes with very specific hole-sizes that encourage these flashy blue migrants but deter non-native starlings and House Sparrows.

I’m Michael Stein.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Song of the birds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Tree Swallow recorded by G.F. Budney. Eastern Bluebird recorded by W.L. Hershberger.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org - for Living on Earth

http://birdnote.org/show/nest-cavities-book-early

CURWOOD: You’ll find pictures at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Learn more about early competition for nesting sites on BirdNote

- Tips for building and maintaining birdhouses

- How to make a birdhouse for just about any bird

- More on the Tree Swallow

- Audubon’s field guide to the Mountain Bluebird

- More about the Mountain Bluebird from Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology

- Audubon’s field guide to the Eastern Bluebird

- More about the Eastern Bluebird from Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology

- Audubon’s field guide to the Western Bluebird

- More about the Western Bluebird from Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology

[MUSIC: Stephen Hough, “Six Songs Opus 25: 2. The Fuchsia Tree (arr. Hough),” comp. Roger Quilter, The Piano Album (Parlophone UK 1998)]

You can hear our program anytime on our website, or get an audio download. The address is LOE.org. That's LOE.org. There you’ll also find pictures and more information about our stories. And we’d like to hear from you: You can reach us at comments@LOE.org. Once again, comments@LOE.org. Our postal address is PO Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199.

And you can call our listener line, at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988.

[MUSIC FADES]

CURWOOD: Coming up...thanks to the lowly fungus, we have truffles and Shiitake and bread and beer – but also white nose syndrome and ugly toenails. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provide building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Stephen Hough, “Melodie in E,” comp. Ossip Gabrilowitsch, The Piano Album (Parlophone UK 1998)]

Beyond the Headlines

Beijing air in August 2005 after two days of rain (left) and later on a smoggy day. (Photo: Bobak, CC BY-SA 2.5)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Let’s take our regular stroll now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org. He’s on the line from Conyers, Georgia. What’s up today, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, Steve, there’s a peer-reviewed study from Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment and Peking University suggesting that breathing Beijing’s bad air can make you fat.

CURWOOD: We’ve heard a lot about Beijing’s bad air, but this is a new one.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, the study was published in the current issue of the Journal of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology – there’s a title that could stand to lose a little weight. It compared rats breathing clean air to rats breathing Beijing quality air, and in only 19 days, the dirty-air rats were 15% heavier, with enlarged lungs and livers, higher cholesterol and triglycerides, and their insulin resistance level was higher – that’s a precursor to rat diabetes.

CURWOOD: What did they say about diet?

DYKSTRA: Well, the researchers acknowledge that diet and exercise are still the main drivers of weight gain, but you know, you can change your eating habits, but not your breathing habits.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Hey, what’s next?

DYKSTRA: I’ve got a story from PRI member station, KQED, in the San Francisco bay area. This year’s Dungeness crab season was ruined by high levels of domoic acid in the crabs.

Sooty Shearwaters off of California’s Monterey County coast. (Photo: J. Maughn, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: What’s that?

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s a neurotoxin that’s produced by plankton and it can work its way up the food chain, as it did back in a case in 1961. There were hundreds of seabirds called Sooty Shearwaters, that after gorging on toxin-filled anchovies, dive-bombed the small coastal town of Capitola, California in the middle of the night, ramming into windows cars & buildings. And the next morning, they were shoveling birds off the street.

CURWOOD: Sounds kinda familiar, I think I know where you’re going here, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, you know, Alfred Hitchcock owned a home nearby, and he took an interest in all of this. He combined the Capitola story with a short story by Daphne du Maurier, and The Birds was a scary box office smash two years later.

CURWOOD: The original “Angry Birds” one could say. Hey, what do you have for us from the history vaults this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, here’s a tribute to some of the paranoia, denial, and scapegoating that sometimes pervades environmental politics: the original American witch hunt.

CURWOOD: Salem, Massachusetts, huh?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, Salem, Mass., February 29, 1692. I always wanted to do a calendar item from February 29. There was a warrant issued for Sarah Osborne on the charge of being a witch. Sarah was a property-owning widow who married her servant, so she was already kind of the Town Hussy. And in early 1692, several children fell ill, and a learned doctor said the cause was “bewitchment”, and the search was on for witches in Salem.

CURWOOD: I didn’t know that was a diagnosis. You know, there’s a theory that the illnesses may have been the result of some contaminated grain, perhaps the ergot fungus, which can make people crazy sometimes.

Ergot poisoning is due to the ingestion of the alkaloids produced by the Claviceps purpurea fungus. Seen here growing on barley, this fungus infects rye and other cereals, and can cause neurological effects like those reported in the Salem witch trials. (Photo: Dominique Jacquin, public domain)

DYKSTRA: Yeah, perhaps, but that would have been a tough sell back in 1692. You know, Sarah was in a property dispute with a neighboring family, who accused her of viciously pinching their children and poking them with a knitting needle—sounds more like Moe, Larry and Curley than witchcraft — so she was brought before a hearing the next day, March 1, where she denied the charges and absolutely nobody believed her.

CURWOOD: And in Salem, Massachusetts, she was not the only one being accused of being a witch.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, well, she never actually made it to trial, having died in harsh prison conditions a couple of months later. Eighteen others were convicted and hanged, and one very unlucky convicted man was crushed to death by heavy boulders. Then some higher powers in the Massachusetts colony came in and pardoned about 140 more accused witches.

CURWOOD: Well, at least today our witch hunts are a bit less messy.

DYKSTRA: But we still have them.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org. Talk to you soon, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, Steve. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Study: Chronic exposure to air pollution particles increases the risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome: findings from a natural experiment in Beijing

- Acid Flashback: Santa Cruz Bird Frenzy, Hitchcock and a Biological Whodunit

- More on domoic acid and its toxicity

- Transcript of First Salem Witch hearing

- Link between the ergot fungus and the Salem witch trials

[MUSIC: Ray Charles with Pancho Sanchez, “Mary Ann,” comp. Ray Charles, Genius Loves Company (Monster Music 2007)]

Fungal Diseases Surge, Threatening Species Around the World

A red spotted newt. These salamanders could be threatened by the fungal disease, bsal (Photo: US Fish and Wildlife Service)

CURWOOD: From white-nose syndrome in bats to the chytrid fungus that kills frogs, fungal diseases are increasingly threatening many animal species around the world. These kinds of infections have become so widespread they caught the attention of Elizabeth Kolbert. She’s the author of the book "The 6th Extinction: an Unnatural History", and recently wrote about the rise of fungal diseases and wildlife for Yale’s online magazine e360. She joins us now from her home in Williamstown, Massachusetts to discuss what might be triggering these fungal outbreaks. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Elizabeth.

KOLBERT: Thanks for having me back.

CURWOOD: So, in this piece you describe a number of different fungal diseases that are impacting wildlife around the world. Let's start with the snake fungal disease.

KOLBERT: Yes, that's a somewhat mysterious one. It was first noticed a decade ago in Florida. People were doing a snake census and they noticed snakes with these lesions on them. And since then it's been found in about 10 states and has caused major die-offs, including one in New Hampshire among a very threatened population of rattlesnakes.

CURWOOD: Yeah, so I guess half of the timber rattlers in New Hampshire have vanished, huh?

KOLBERT: Exactly, and that was a very small population to begin with, so that raised alarms.

CURWOOD: How does the fungus affect the snakes?

KOLBERT: Well, very recent research shows that it eats the scales of the snakes and it causes these skin lesions, and lesions even, I think, in their internal organs, and that's how it kills them.

Fire salamanders in Europe have been devastated by the fungal disease, BSal (Photo: Aah-Yeah, Flickr CC BY-2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, in your piece you say that there is a huge impact on salamanders in Europe — hasn’t come to North America yet, I gather.

KOLBERT: That's a newly emerging fungal disease. It's become known as "Bsal". It's in the same sort of family as the fungal disease that’s afflicting frogs. And what happened in Europe is people started noticing in Belgium and the Netherlands that these salamanders, known as the fire salamander, that their populations were crashing. Some of them were even eliminated. And they traced it pretty quickly to this imported disease. It seems to have come in on, probably on amphibians that were recorded as part of the pet trade or exotic animal trade from Asia. And because of the absolute devastation that has occurred because of the fungal disease that's afflicting frogs and toads, scientists really jumped on this and said, let's try to prevent this disease from spreading. So a group of scientists in Europe did experiments, and they showed that this particular fungus could be fatal to a lot of different species of salamanders. North America is actually the center of salamander diversity, so American scientists, researchers, were very concerned that we could also get this disease either from some animal that was imported from Asia or one that's now imported from Europe. So they actually petitioned the Fish and Wildlife Service, which has the power to restrict imports under something called the Lacey Act, which is an old, from the beginning of the 20th century act. And just recently, the Fish and Wildlife Service announced it was going to restrict salamander imports because of fear of this disease spreading to the US.

Timber rattlesnakes are threatened by Snake Fungal Disease. (Photo: Tom Spinker, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So there's a big problem for salamanders in Europe, big problem for snakes here in North America, big problem now for bats in North America. What's going on here? Is this just a coincidence that this is all happening at once?

KOLBERT: Well, that is sort of the question at the center of all this. I know it was certainly the question that prompted me to write that piece for e360, and the answers were not sure. People looking at lists of new and emerging diseases have noticed that fungi are playing a bigger and bigger role. And the question of whether that is a function of the effect that fungi are extremely adaptable, they travel really well, they can cross oceans very easily, they can be dormant for a really long time and then bring spring back to life under the right circumstances — or whether it is perhaps more of a symptom, rather than a cause. Fungal diseases tend to infect people with compromised immune systems. So are we seeing sort of globally compromised immune systems in wildlife, and is that giving fungi an opportunity, so these are opportunistic infections, and is that why we’re seeing it now.

CURWOOD: Let's tease these apart. So one theory here, then, is that this is all the function of being invasive species, that the fungi are coming to places where they haven't been before and the animals are susceptible. What's the evidence for that? What's a good example of that?

KOLBERT: White nose syndrome, which is the bat killing fungus is a pretty good example of that. This is a fungus that has been traced back to Europe. It's pretty clear it was introduced to the US from Europe and perhaps even by some unsuspecting tourist, but what we saw with that disease is we saw it come — literally — we saw the first populations being hit in up state New York, and we saw it spread from there, as you would imagine with a new kind of infection. So that, I'd say, is the best example of something that we're pretty confident is a recent introduction.

CURWOOD: But this snake fungal disease doesn't follow this pattern, so what could be going on there?

A hibernating little brown bat afflicted with white-nose syndrome (Photo: US Fish and Wildlife Service)

KOLBERT: Right, well that is the snake fungal disease which seems to have popped up in different places, more or less at the same time, and in places that are not even, you know, contiguous. There, scientists who have looked at it seem to be more convinced that this is something that is not just a recent introduction. Now the question is whether it's been around for a long time, and it would be weird for it suddenly to become more virulent in these disparate parts of the world simultaneously. That would sort of be statistically very unlikely. So then the question is, are snakes being laid low by other factors, and therefore have these compromised immune system, and this pathogen has now become more deadly because they just can't fight it off.

CURWOOD: So, what could increase the stress for snakes and salamanders?

KOLBERT: Well, unfortunately, you know we barely have time to talk about all the things that are going on in the world that could be compromising the immune systems of creatures that are out there trying to survive in a very rapidly changing world, as your program has documented over and over again. So, what could be affecting snakes? Climate change, right? So, snakes are cold-blooded. They are very responsive to changes in climate, they may be very responsive to changes in moisture, the fungi may be very responsive to changes in temperature and moisture, so that's one thing. We may be looking at pollution of all sorts, right, toxins, heavy metals, you name it. We're looking at habitat destruction, obviously snakes have preferred habitat, they're being squeezed into tighter and tighter territories. Unfortunately, the list kind of goes on and on.

CURWOOD: The last time we spoke, we were talking about your book "The Sixth Extinction". How does what's going on here with fungal disease play into the arguments you were making in the book?

Writer Elizabeth Kolbert (Photo: Barry Goldstein)

KOLBERT: Well, they're very sort of vivid examples of what I was talking about, perhaps the most vivid, because they are diseases that are hitting many, many species simultaneously, and in several cases that we know of, they were caused by moving stuff around the world. So as we move more and more cargo, as we travel more and more, as the world becomes more interconnected, we are effectively bringing together these evolutionary lineages that have been separated for tens of millions of years. And we are getting a lot of nasty surprises and there's no reason, unfortunately, to think that that is going to end. These interactions are just increasing, and the more you have, even if only a very small fraction of them turn out to be dangerous, you're moving thousands and thousands of species around the world, every day, you just need a very tiny percentage of them to be deadly to create a really, really big problem.

CURWOOD: Now, you've talked to a lot of scientists as you were writing this piece. Who among them has some hope? What do people site as a sign of hope in the face of something as devastating as this?

KOLBERT: Well, I think that one hopeful sign that scientists would point to, and this is a very recent development so I haven't really spoken to people since it happened, but it is that people are waking up to this problem. And so for example, scientists went to Fish and Wildlife, presented evidence that this was a real potential threat and that we need to take preventive steps. And Fish and Wildlife did respond to that, so I think people would point to that as a sense that we've been warned and we are taking that warning seriously.

CURWOOD: Elizabeth Kolbert’s article on emerging fungal diseases is in the journal e360 from Yale. Thanks so much for taking time with us today, Elizabeth.

KOLBERT: Always a pleasure to talk to you guys.

Related links:

- Read Elizabeth Kolbert’s article in Yale’s online magazine e360

- Fish and Wildlife Recently Decided to Restrict Salamander Imports to Prevent Spread of BSal

- More about white-nose syndrome in bats

- Chytrid Fungus and Chytridiomycosis

- Elizabeth Kolbert’s latest book is called the 6th Extinction: an Unnatural History

- Elizabeth Kolbert writes for The New Yorker

Microbes Fight Fungal Disease in Frogs

Spotted salamanders, Ambystoma maculatum, from Milton, MA. (Photo: Doug Woodhams)

CURWOOD: And there is more good news beyond the actions taken by the Fish and Wildlife Service to keep infected salamanders out of the US as part of the fight against fungal diseases that are devastating animal populations. Biologists also see some potential hope in soil bacteria that get onto the skins of salamanders and frogs. Doug Woodhams is an assistant professor of biology at UMass Boston, who’s been working with amphibians in Panama – and he explained what his team has found to Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Now, we’ve just been hearing about the terrible problems that seem to be attacking many different species at the moment, many fungal diseases — things like white nose syndrome. You’ve been looking at the kind of diseases that attack frogs and salamanders, and you’ve found some good news.

WOODHAMS: Yes, so some of the amphibians have beneficial bacteria that live on their skin, and these have anti-fungal properties.

PALMER: This is kind of like having good bacteria in your gut, for instance, that stop you from getting sick.

WOODHAMS: Exactly, yeah. So the amphibian skin is a mucosal surface, just like our guts. And they are also protected by microbiota.

PALMER: And is there any evidence that these good bacteria actually work against these devastating funguses?

WOODHAMS: Yeah, there’s quite a bit of evidence. Many of the bacteria that we can culture from some amphibian species are able to inhibit the fungus in culture. We also have some population-level data that shows populations that tend to have these anti-fungal bacteria can persist with Bd in the environment and survive—

PALMER: Bd is?

WOODHAMS: Bd is the chytrid fungus that’s been spreading around the world and devastating amphibian populations. So salamanders, frogs, toads, they’re susceptible to chytrid fungus.

Doug Woodhams studies disease ecology and teaches at the University of Massachusetts Boston. (Photo: Harry Brett)

PALMER: We’ve seen the chytrid fungus that affects frogs spread all around the world and wipe out massive amounts, particularly of certain frogs. If the salamander fungus is not here, then presumably the danger is once it gets here it will have a similarly devastating effect because they won’t have any immunity.

WOODHAMS: Absolutely, and that’s why — you know, it may be only a matter of time before it arrives. So that’s why there’s a recent increase in the concern and research activity, trying to figure out which amphibians, which salamanders — even frogs may be susceptible, we don’t know yet. And especially in the Appalachians, where it’s the world’s hotspot of salamander biodiversity, we really want to keep this new salamander chytrid out. And if we can’t, then we need some tools, for example, probiotics or anti-fungal treatments, that may be able to help.

CURWOOD: That’s just a taste of what UMass Boston biology professor Doug Woodhams told LOE’s Helen Palmer about the new discoveries that might help save salamanders and perhaps other wildlife under threat from fungal diseases. We’ll have the full interview next week.

Related links:

- Dr. Woodhams’ paper, “Managing Amphibian Disease with Skin Microbiota”

- About Bd and other chytrid fungi

- About the Bsal salamander fungus

- Dr. Doug Woodhams’ lab

- Elizabeth Kolbert, “What’s Causing Deadly Outbreaks of Fungal Diseases in World’s Wildlife?”

[MUSIC: The Re-Stoned, “Crystals,” Analog (R.A.I.G. 2011)]

EARTH EAR – ROCKY MOUNTAIN FROGS

[FROG CHIRPING]

We leave you this week – in the company of frogs. These are Pacific Chorus frogs, once prolific and common around California – and providing an outdoor nighttime soundtrack for many Hollywood movies.

[FROG CHIRPING CONTINUES]

When they sense there’s a female near, males call to attract her.

They breed from November through July, so you could well hear them now if you have ponds nearby.

Carlos Davidson recorded these Pacific Chorus frogs for the CD Frog and Toad Calls of the Rocky Mountains.

[MUSIC: Miles Davis & Quincy Jones, “Solea,” comp. Miles Davis, Live at Montreux (Warner Bros. 1993)]

Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Peter Boucher, Jaime Kaiser, John Duff, and Jennifer Marquis. Jake Rego engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Tom Tiger and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. And Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change.

Also from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth