March 25, 2016

Air Date: March 25, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Lead Found in 2,000 US Public Water Supplies

View the page for this story

A recent investigation into water-lead levels across the country by USA Today found that 2,000 water systems beyond the troubled one in Flint Michigan pose a risk. USA Today journalist Alison Young sat down with host Steve Curwood to discuss the dangerous legacy of America’s lead pipelines and the health risks involved in ingesting even small amounts of the neuro-toxin. (07:50)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip Beyond the Headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about environmental and political problems in Brazil, and several efforts to protect bees by banning neonicotinoid pesticides. Then they take a look back at two of the biggest earthquakes ever recorded, and the ensuing tsunami disasters. (04:35)

Reducing the Costs of Air Pollution

/ Reid FrazierView the page for this story

Particulates and other emissions from burning fossil fuels are costly for human health; the WHO argues 3.3 million people die prematurely due to this pollution. But in the US utilities are shifting from coal power, and the costs of illnesses triggered by pollution is falling. Reid Frazier of the Allegheny Front reports. (05:00)

Science Links East Coast Snows to Arctic Warming

View the page for this story

Scientists can spot global climatic changes by tracing slight variations in the isotopes in water molecules. Researcher Myron Mitchell tells host Steve Curwood how his team analyzed the water from the Hubbard Brook research station to show that the Arctic is now sending the Northeast more water than in recent history, especially snow when it comes to snow. This reinforces a theory of Rutgers climate scientist Jennifer Francis that links loss of arctic sea-ice with colder winters in the Northeast. (07:50)

Polar Bear Cubs in Danger

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

In Akpatok Island in the Canadian arctic, writer Mark Seth Lender watches an enormous male polar bear comes frighteningly close to a mother bear and her two young cubs. Will she flee and surely save herself, or heed her instinct to protect her cubs? (02:55)

BirdNote®: Strange Birds from Down Under

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Isolated from all other rainforests on Earth, in Northeastern Australia they are home to many unique species. BirdNote's Mary McCann describes some of the peculiar-looking birds found only "down under". (01:55)

London Fog: The Biography

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Cities have unique signatures, and for London, that’s fog. A century ago, acrid, corrosive soot-laden smog killed thousands and shrouded the city in darkness. Yet some Londoners felt affection for the fog; they called it “the London Peculiar”, and it featured in books, art and on the screen. In “London Fog, The Biography”, Christine Corton profiles the heyday of this miasma and she tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer what it took to clean the air up. (16:50)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Alison Young, Jennifer Francis, Myron Mitchell, Christine Corton

REPORTERS: Reid Frazier, Mark Seth Lender, Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann, Helen Palmer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. New analysis of US water way beyond Flint Michigan reveals at least 2,000 systems where levels of lead exceed EPA limits – and over seven million households have this toxic metal in their pipes.

YOUNG: Exposure to lead affects children's IQ, their ability to learn in school. Pregnant women are at significant risk, even, sort of, grown adults. I mean, there is no known safe level of lead exposure.

CURWOOD: Also, burning fossil fuel adds to global warming and can make people sick.

VENKAT: What happens a lot with these patients is that either allergies due to air pollution or they get a virus of some sort. That really triggers them to require acute care, and pollution is a, it’s a well-recognized trigger.

CURWOOD: But as air here gets cleaner, fewer people are falling ill. That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME RETURN]

Lead Found in 2,000 US Public Water Supplies

Is the water coming out of your tap safe to drink? USA TODAY found that 2,000 water systems across the U.S. had excessive levels of lead in tests conducted over the past four years. (Photo: Joe Cheng, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. As many as 2,000 drinking water systems in America are contaminated with lead, an investigation by USA Today has found. Also as many as seven million American households are at risk of lead poisoning because of their pipes. USA Today launched its investigation after the Flint, Michigan, water disaster burst into the national spotlight recently, 18 months after a cost-cutting measure resulted in unsafe levels of lead in the pipes. One of the journalists on the USA Today team, Alison Young, explained why they took on this huge investigation.

YOUNG: Obviously, everyone at this point has heard about the serious contamination issues in Flint, Michigan, but we wanted know how many other places might be having, maybe not at this level but maybe having issues with lead in their water.

CURWOOD: Now, I gather you didn't go visit all of these water systems. Where did this data come from?

YOUNG: EPA keeps water enforcement data and it's sort of a bear to go through, but by going through it, we were able to identify these systems that had not met the very minimal standards that EPA has for lead in water. But we also found that the standards are not adequately protective, and just because you're not in the system that's on our list of 2,000 that we have on our website does not mean that your water in your individual home is safe.

CURWOOD: Oh, really? So what are the limits that the EPA looks for and what are the safe limits?

YOUNG: Part of what they're testing to is what's called an “action level” for lead. It's 15 parts per billion of lead in water. As you dig into that, it's not a safety standard, and the EPA will be the first one to say that that is not a safety standard.

CURWOOD: Wait a second. It's not a safety standard, but they're basing regulation on something that is not a safety standard?

YOUNG: It is something they call a“treatment technique” standard. It's an achievable limit that they believe can and should be achieved in water, and part of the issue here is how lead is getting into our drinking water. This is not an issue where water systems are failing to screen it out at the water treatment plant. This is a very unique problem in that the lead is getting into our water as a result of the legacy of having used lead in our pipes and in our plumbing going back many decades. Even if your water system is treating your water perfectly with anticorrosion chemicals, water will still erode led from pipes, so there is no way of eliminating the problem unless you actually eliminate the pipes. What's happened in Flint is result of that water system in Flint, Michigan, switching to a very corrosive river water source, and then they didn't treat it properly, and it basically stripped the insides of pipes and set torrents of particles and lead into people's homes.

An estimated 7 million homes in the U.S. are served by lead pipe service lines. (Photo: Michael, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Talk to me, by the way, about the risk of lead poisoning and why children are particularly at risk from it.

YOUNG: Sure. I mean, lead is a very powerful neurotoxin. It harms developing brains of children. The studies have found that exposure to lead affects children's IQ, their ability to learn in school. It’s associated with attention disorders and other problem behaviors. Pregnant women are at significant risk and even sort of grown adults. I mean, the studies indicate associations with high blood pressure, kidney problems and potential cardiac issues. There is, according to the EPA and the CDC, no known safe level of lead exposure, and as the science continues to progress there are documented harms at lower and lower levels.

CURWOOD: I see. So you looked at this EPA data, they had samples from various homes from some 2,000 additional water systems. What were they doing about that?

YOUNG: In some cases they came back into compliance the next round of testing, but in others, I mean, we found a water system in rural Oklahoma that repeatedly over the course of a couple of years kept failing its lead tests, and there, in fact, were numerous systems across the country that have had over and over and over again tested with high levels of lead in these taps, which raises concerns about what may be going on in other homes in those communities.

CURWOOD: And what did the EPA do about these places where these questions were being raised time and time again?

YOUNG: It's a difficult thing to untangle because there're multiple layers of regulation. The EPA sets the federal regulations, but it has delegated the authority to actually enforce and follow those regulations to state agencies all over the country. One of the more disturbing things we found is that there were numerous systems that failed to inform their customers when they fell out of compliance with these EPA lead regulations, and that's a very serious issue because one of the things that I came away with from this investigation is that we as consumers must be educated and take action to protect ourselves from lead coming out of our taps.

CURWOOD: Now, what communities or what regions are most vulnerable to lead contamination in the water supply?

YOUNG: The experts we've talked to say that the issue is primarily in older areas especially along the East Coast and in the upper Midwest, but there is the potential for lead to be in any home built before 1986. In addition to those there are an estimated 7.3 million homes across the United States that are believed to be served by what are called lead service lines. It's a huge issue, and one of the recommendations from expert panels to the EPA is that we must develop a strategy in this country to remove and replace these lead service lines, but the estimates of doing that are going to run in the tens of billions of dollars, and finding that money is going to be difficult.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about your own experience in trying to get information about the lead content of your water system at home. I imagine you asked that question once you did this investigation.

Alison Young (pictured above) and Mark Nichols organized a team of journalists across the country to compile a lead-water investigation for the USA TODAY Network. (Photo: courtesy of Alison Young)

YOUNG: I absolutely did. In fact, my editors had me write a first-person piece as part of the project, just checking out my house. I live in a historic district just outside of Washington, D.C., in a row house that was built in 1880. It is the kind of house that is very much at risk of having lead plumbing components. One of the things that experts say to do is call your water company, the people you pay your bills to. Unfortunately I had a very difficult time getting a straight answer from my water company when I called as Alison Young just consumer, not as Alison Young reporter. What they ultimately were able to tell me is that a portion of my service line, the portion that they owned was replaced with copper in the 1980s, and while that might seem like good news it’s potentially not good news. There are some concerns that doing what's called a partial service line replacement might actually increase the amount of corrosion when you put those two metals together.

CURWOOD: At the end of the day what can consumers do to protect themselves against this danger?

YOUNG: It seems that you know from those that I've interviewed, their best advice is if you're in an older home that likely has lead plumbing and pipes, to consider installing a water filtration device on your tap that's used for cooking as well as for drinking, and there're a number of experts that I interviewed who also said that if you have an infant and you're making infant formula with tap water, stop doing that. It's just - the tap water is potentially a significant risk, if it’s contaminated with lead, if you're making formula with it. Those little bodies, their threshold for lead, it's just something you don't want to be messing with.

CURWOOD: Alison Young is a member of the USA Today network investigative team. Thank you so much for taking time with us today, Alison.

YOUNG: Thank you.

Related links:

- EPA drinking water rules for lead and copper

- USA TODAY’s Original Lead Investigation

- Allison Young Looks Into Her Home Water-Lead Levels

- SDWIS Database Formed Basis of USA TODAY Findings

Beyond the Headlines

The Petrobras headquarters in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Photo: Felipe Lange Borges, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now we’ll check in with Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org and burrow beyond the headlines. Peter joins us on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. You know that discussion about lead reminds me of what happened last week in Washington at a Congressional hearing in which EPA was raked over the coals for inaction in Flint, Michigan. Some of the Congressmen who were raking EPA over the coals were the same folks who have helped cut its budget by 20 percent in recent years, since 2010, and also have called for the abolition of the EPA, so you can’t have your lead and eat it too.

CURWOOD: Ha! Sounds like bricks without straw. Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Let’s talk about some of the many ways in which the great nation of Brazil is in kind of a mess right now.

CURWOOD: They’ve certainly gotten their share of attention for pollution at the Olympic sailing site.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, just over four months until the Olympics start in Rio, and Olympic officials say there’s no way they can clean Guanabara Bay by then. But a poop-filled sailing venue may be the least of the problems. A recent piece in The Guardian quotes a longtime Brazilian journalist saying, “I’ve never seen it so bad,” in terms of the killing of activists in the Amazon rainforest. 45 were killed last year alone.

CURWOOD: Yeah, it’s tough. We just reported a couple of weeks ago on the murder of Honduran activist Berta Cáceres, and since then another of her colleagues was killed.

DYKSTRA: Brazil’s Pastoral Land Commission says nearly 1,000 environmental and indigenous rights workers have been murdered there since 1964. And Brazil is also in the middle of a massive oil scandal that could topple its government.

CURWOOD: Boy, this is not a particularly good time for that with the Olympics coming.

DYKSTRA: Well, here it is. Petrobras, the Brazilian National Oil Company, is at the heart of a massive bribery and kickback scandal involving billions of dollars. The allegation is that contractors charged hugely inflated prices on Petrobras construction projects, gave some of the proceeds back to Petrobras execs and government officials as bribes and pocketed the rest. This is said to have gone on for a decade, and President Dilma Rousseff could be facing impeachment. But let’s move on to the B Block.

CURWOOD: OK, the B block it is, what have you got?

DYKSTRA: Bees, of course. Two years ago, the EU placed some limits on the use of neonicotinoid pesticides suspected in multiple scientific studies of being a major cause in the crash of bee populations. The French National Assembly has just gone them one better, narrowly approving a complete ban on neonics. If that passes the French Senate, the ban would take effect in 2018.

Neonicotinoid pesticides, or “neonics”, pose a significant threat to bee colony health. (Photo: Brad Smith, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: But neonicotinoids aren’t the only suspects in the bee declines.

DYKSTRA: That’s correct, a parasite called the varroa mite, habitat loss, other pesticides, and many other things could also be to blame. Here’s one domestically. The State of Minnesota made its first payouts recently under a two year-old law offering compensation to beekeepers whose hives are damaged by pesticides. Two beekeepers filed claims that their hives were destroyed by drift from nearby cornfields, and the state will pay them $230 per hive for their losses. The U.S. EPA has determined that there’s a link between the chemicals and bee loss. Some other states like Vermont and Maryland are considering bans on neonics, and the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec already have banned them.

CURWOOD: Hmm. Hey Peter what do you have for us this week from the History vaults?

DYKSTRA: Well, if we have bees in the B block, let’s talk about the sea in the C block. Specifically two historic tsunamis linked to immense earthquakes. It was Good Friday, 1964, a magnitude 9.2 earthquake rocked southern Alaska, heavily damaging Anchorage and wiping out much of the port of Valdez. 131 people died, including eleven that were lost in a series of tsunami waves that hit Crescent City, California, about fifteen hundred miles away from the epicenter. When Valdez was rebuilt, it was rebuilt in a completely different place a few miles away, a bit more protected from tsunamis.

Crescent City, California following the 1964 tsunami that killed eleven people there. (Photo: David Berry, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: You know Peter, 9.2 would make it one of the biggest quakes ever recorded.

DYKSTRA: Just like the 2011 quake in Japan, which the US placed at 9.0.

CURWOOD: And we just marked the fifth anniversary of that one earlier this month, along with the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

DYKSTRA: Right, but this week is the 45th Anniversary of the first of the six reactors at Fukushima going online. Reactor One was the first built. It was also the first to experience a hydrogen explosion which led to a meltdown after the tsunami engulfed the nuke complex, triggering one of the worst nuclear accidents in history.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is with EnvironmentalHealthNews, that’s EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org. We’ll talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Guardian: ‘Never seen it so bad’: violence and impunity in Brazil’s Amazon

- Vox: Brazil’s Petrobras scandal, explained

- Reuters: France moves toward full ban on pesticides blamed for harming bees

- Star Tribune: In win for beekeepers, Minnesota links insecticide to damaged hives

- The 1964 Good Friday earthquake

- Tsunami: 1964 video of deadly tidal wave washing into Crescent City

- The 2011 Tohoku quake

- About the Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear plant and its opening 45 years ago

[MUSIC: Paul Rishell & Annie Raines, “I Shall Not Be Moved,” I Want You To Know, Traditional/arr.Rishell&Raines, Tone-Cool Records/Rounder Records Group]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...scientists say Arctic snow sometimes falls on the US northeast, thanks to global warming. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Osland Saxophone Quartet, “Cityscapes: Lakeshore Drive (Chicago),” Commission: Impossible, Rick Hirsch, Sea Breeze Records]

Reducing the Costs of Air Pollution

A nighttime view of the Keystone Generating Facility, a coal-fired power plant in southwestern Pennsylvania. (Photo: Zach Frailey / Uprooted Photographer)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. When industry complains about the economic costs of environmental regulation, it rarely mentions the costs of pollution to society. Yet according to the World Health Organization, thanks to air pollution, every year some 3.3 million people worldwide die prematurely. But among those stark numbers there is some good news in the US, where more than 200 coal-fired power plants have been retired in recent years, lowering the amounts of fine particle pollution. The Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier went to see how the costs of cleaning up the air are generating huge public health dividends.

FRAZIER: For years, scientists have known that air pollution from burning fossil fuels is bad for us. But can we place a dollar amount on the hidden costs of burning coal and other fossil fuels for electricity? One person who wanted to know was Paulina Jaramillo.

JARAMILLO: I study the environmental impacts of energy systems.

FRAZIER: So the Carnegie Mellon scientist called up a colleague. They designed a model to find out.

The researchers plugged in pollution reports from the EPA, weather models, and population data. They took into account the effects of pollution on crops, forests, and infrastructure. And human health. Much of that cost hinges on one basic number, and it’s kind of a creepy number.

JARAMILLO: Value of a statistical life, which is a number widely used in policy analyses to estimate mortality costs.

FRAZIER: The value of a statistical life. It’s basically the amount of money we as a society are willing to spend to save someone’s life. And according to the federal government, it’s around $6 million these days. What the scientists found was pretty clear. Since the early 2000s, emissions from coal-fired power plants have been going down. And because of this, Jaramillo found that the annual cost of pollution declined by about 25 percent, to $130 billion.

Coal-fired power comes with a high price tag, largely because of adverse health effects. (Photo: KristyFaith, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

JARAMILLO: Because we started reducing these emissions we reduced health impacts...These models cannot pinpoint who is specifically benefitted, but on a population basis there are benefits.

FRAZIER: So, what happened? Jaramillo says the big change is that new regulations forced many coal-fired power plants to clean up. The Great Recession lowered demand for energy for a few years, and cleaner sources, like natural gas, have cut into coal’s share of the electricity market. Though these costs may be going down, the price-tag the researchers calculated is still around $400 a year for every person in the U.S. Where can you see these costs play out in real life? You can try the emergency room at Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh.

VENKAT: Over here we have our X-ray suites. Most of these patients that are involved, they will require some X-ray study to see if they've developed a pneumonia, for example, on top of their underlying condition.

FRAZIER: Arvind Venkat is an emergency physician at the hospital. Venkat says his patients will come in because of a cold or allergic reaction, but the underlying causes include lots of other factors, including air pollution.

Severe air pollution in China’s Henan Province (Photo: V.T. Polywoda, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

VENKAT: What happens a lot with these patients is that either allergies due to air pollution or they get a virus of some sort - that really triggers them to require acute care, and pollution is a well-recognized trigger.

FRAZIER: Studies show that ER visits for heart and lung conditions go up on days when pollution is highest. And at around $1,000 bucks a pop, costs for ER visits for people with breathing problems can add up.

[TALKING]

DOCTOR: You have your inhaler at home?

DEVER: I have it with me, here.

FRAZIER: That cost was visible one day last year, when 60-year-old Linda Dever visited the emergency room.

DEVER: About 3 o’clock this morning, I woke up, the whole right side, I couldn't breathe. When I tried to inhale, it just hurt so bad, I couldn’t inhale.

FRAZIER: Dever was a smoker until a few years ago. But since being diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, she’s been to the ER about once a year.

DEVER: I drive a school bus, and when I leave to the lot and walk up to my car, just a little bit of a grade, as soon as I get in my car, I have to get my inhaler out and use my inhaler, ‘cause I can't breathe.

FRAZIER: There’s no way of knowing whether pollution in Pittsburgh’s air had anything to do with Dever’s breathing problems that day. But pollution has been shown to cause the same types of symptoms that make lung conditions like hers worse and an ER visit more likely. For Jaramillo of Carnegie Mellon, the takeaway from her study is simple...

JARAMILLO: Well I think my take (away) is we need to continue regulating these emissions and putting controls on these emissions, because they have been effective.

FRAZIER: And if emissions from places like coal plants continue to decline, so will their costs. I'm Reid Frazier.

CURWOOD: Reid Frazier reports for the Pennsylvania public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Study: Air pollution emissions and damages from energy production in the U.S.: 2002-2011

- About air pollution caused by coal-fired power plants

- The Allegheny Front

[MUSIC: Tarika,“Bonne Annee,” D, Bodisy Jean Rene OMDA, Xenophile/Green Linnet]

Science Links East Coast Snows to Arctic Warming

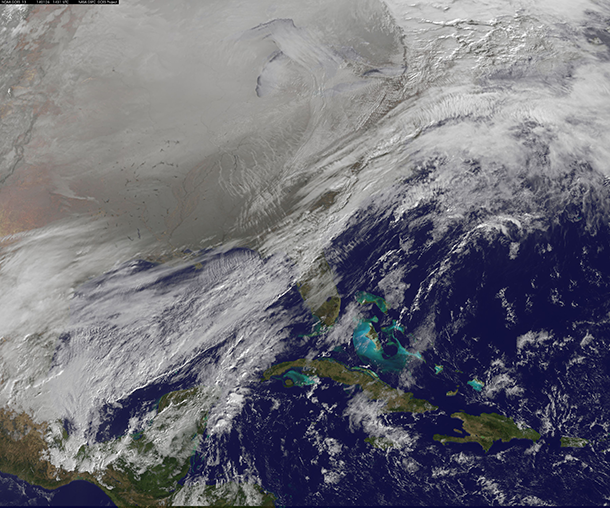

Image of eastern North America captured by NOAA’s GOES-East satellite on January 6, 2014. A frontal system that brought rain to the coast is draped from north to south along the U.S. East Coast. Behind the front lies the clearer skies and bitter cold air associated with the polar vortex. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: We call it “global warming,” and in many places, average temperatures are increasing, yet in other places a changing climate can mean colder weather. Jennifer Francis, a climate researcher at Rutgers University, was the first to suggest a link between the loss of Arctic sea ice and colder winters in parts of the Northern Hemisphere. She described her hypothesis to Living on Earth back in 2014.

FRANCIS: There's only about half as much sea ice coverage in the Arctic now as there was only 30 years ago. It's just been disappearing at an amazing rate. One of those regions where the ice is disappearing the fastest is just north of Scandinavia and western Russia, an area called the Barents-Kara Sea area. What we're learning about this area is that it's very important for the atmosphere.

When we lose that ice there, the dark ocean underneath during the summertime absorbs a lot of extra energy from the sun, and so that water warms up a lot more than it used to. When fall comes along and the cold air starts to move in again, all that energy that was absorbed through the summer in that region then gets re-emitted back to the atmosphere, and that causes the air above this region to warm up a lot.

This has the effect of actually bulging the jetstream northward. The jetstream is this fast-moving river of air, high over our heads, that generates the weather that we experience down here on the surface, and when it is forced to bulge northward like that it compensates by bulging southward just downstream, which would be to the east. When that happens, it allows the cold air from the Arctic to plunge farther south, and so what we're seeing is, during summers when there's less ice than normal in this Barents-Kara Sea area we're finding the jet stream taking this wavier path with the bulge up north of Scandinavia and then a big dip south over Asia allowing that cold air to plunge southward and creating those colder winters.

When the Arctic Vortex descended over the eastern half of North America in January 2014, the weather system brought such cold air that it froze the Chicago River. (Photo: Sean Benham, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now there’s new evidence to support this hypothesis of Jennifer Francis, in a study that drew on more than forty years of water samples taken at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire. Using isotopes of the different elements of water as fingerprints, scientists were able to determine much of the precipitation in snowy years in that New Hampshire forest had arctic origins. Myron Mitchell is one of the study co-authors and joins us now from Syracuse, New York. Myron, welcome to Living on Earth.

MITCHELL: Thank you for having me.

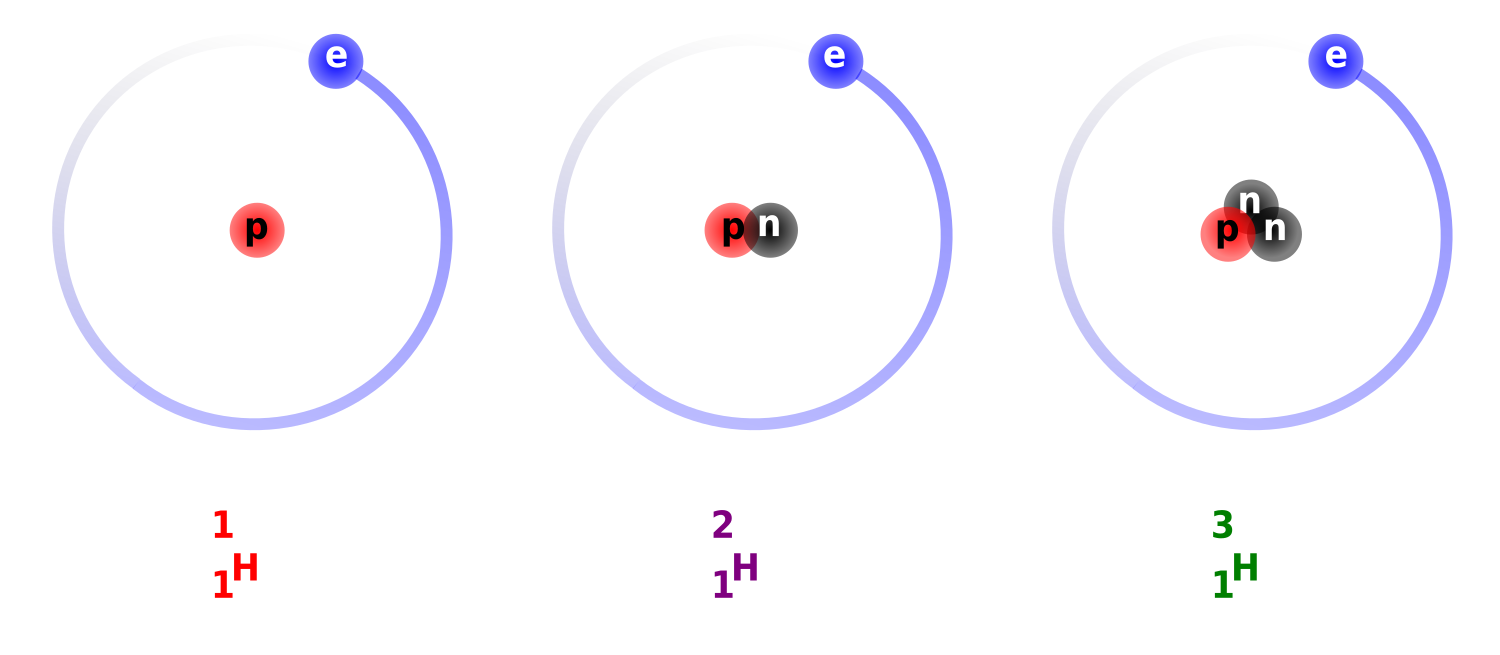

CURWOOD: So, let's do a little basic chemistry here. What is an isotope and what isotopes are particularly useful in studying water?

MITCHELL: Sure. So almost all elements have different isotopes, and for water, the two major elements of water are hydrogen and oxygen. All elements within the nucleus have two subatomic particles, neutrons and protons, and they also have electrons which circle the nucleus. And the number of protons in the element stays the same, but the number of neutrons can change and the water molecule can vary with respect to the hydrogen isotopes and the oxygen isotopes. For instance, for hydrogen they have hydrogen one which just has a single proton. You can also have hydrogen two which has a proton and a neutron, and then you have oxygen 16, and you have oxygen 18 which has two more neutrons which makes it a little bit heavier.

Hydrogen has three naturally occurring isotopes: 1H, 2H, and 3H. (Photo: Dirk Hünniger, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: So when you look at the different isotopes that make up the hydrogen and oxygen and water, you're able to tell where water has been and where it's gone, I gather.

MITCHELL: To a certain degree. It's not a completely simple story, but it does give us some ideas. For instance, the water that comes from the Arctic Ocean is going to have a different isotopic value than the water comes from the Southern Atlantic. These differences don't affect the chemistry of water but they actually can be used as a tracer, giving us information of where the water comes from. But we also do some back projectory modeling, the model developed from NOAA, and we use these models to backtrack where the precipitation that came to Hubbard Brook, did it come from the Arctic? Did it come from the northern Atlantic? Did it come from the southern Atlantic? And we found there was a good correspondence between those modeled analyses using mathematical models and our actual measurements.

CURWOOD: Now, talk a little bit more about your detective work here. Why are there different isotopes different places on Earth?

Myron Mitchell and his colleagues analyzed water samples collected over more than 40 years at Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire. (Photo: Mariel Carr, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

MITCHELL: It has to do with, there are certain physical processes which result in some small discrimination of a wider isotope versus the heavier isotope. An easy example would be, let's say you have some water which is sitting in a container, and you warm that water. The water that comes off of that container is evaporated, and the evaporated water has a little bit lighter isotopes than the water which remains within the container. So therefore evaporation is one process which results in a change in the isotopic value of water. So what's happening as the Arctic Ocean has increased in temperature, also increased in size because of the absence of ice, we're getting more evaporation from the water associated with the Arctic, and that's contributing to the water coming down into the northeast United States and elsewhere. So it's changing the weather patterns, and as it changes the weather patterns we can see where the water that comes from the vortex is affecting the precipitation amounts in the northeast United States.

CURWOOD: Now, how important is the Hubbard Brook experimental forest to all of this research?

MITCHELL: It's very important because it is a research station which started in the 1950s, and, therefore, developed a very long-term record of environmental change. It was one of the first places in the United States in which acid rain was determined. And it's particularly unique in that, not only have samples been collected for long periods of time at Hubbard Brook, but also these samples have been stored in an archive so people can go look at these samples and use these samples for helping to understand how things have changed over time.

CURWOOD: So, where do you go next with doing research on the distribution of water isotopes?

Myron Mitchell is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, New York. (Photo: courtesy of Myron Mitchell)

MITCHELL: Well, we want to actually look at the water isotopes found within the drainage waters of Hubbard Brook, which we have the measurements for, and looking at the oxygen within the wood to see if there's a correspondence between what's happening within the water and what's happening within the trees at Hubbard Brook, and we should be able to see a correspondence between those isotopes.

CURWOOD: What could that tell you?

MITCHELL: That would allow us to look at trees over a larger area where we don't have this very intensive precipitation record, and we could actually do extrapolation and see how things are varying over time and across areas of the region, and maybe even beyond our region to other regions as well.

CURWOOD: Myron Mitchell is a distinguished professor at the College of Environmental Science and Forestry at the State University of New York in Syracuse. Thank you so much, Professor.

MITCHELL: Thank you.

Related links:

- Nature Paper: “Arctic Vortex changes alter the sources and isotopic values of precipitation in northeastern US”

- Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest

- What is an isotope?

- About Myron Mitchell

Polar Bear Cubs in Danger

Two polar bear cubs scrambling after their mother (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Arctic history is written in isotopes found in the ocean, and frozen in layers of blue glacial ice. Arctic wildlife also has its history and continuing displays of loyalty and animosity. On Akpatok Island in Hudson Strait writer Mark Seth Lender witnessed both.

The Wages of Fear

© 2015 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: She comes down the slope slipping and sliding on the scree and not quite at a run (an exercise in self control): just about keeping up behind her, two white cubs-of-the-year. Button noses, rounded little ears and the size of a sack of coal, each one of them. They don't know what or why, only the urgency and follow blindly in her track as if she were breaking trail in deep snow.

Good for them if they keep up and keep going.

Bad, if they stop to ask what for.

All in a scramble they make the beach and along until the coarse limestone sand comes to an end in shelves of rock like a pair of overlapping hands. She strides over, stepping easily from one upturned palm of stone to the other, and the cubs stretched full length hoist themselves after; as if, something is after them.

Something is after them...

He is big. Even for a polar bear. He climbed, high. Like, nothing better to do. Like boredom. At random. On columnar limbs near five feet tall at the shoulder. Traveling in the steep ravine on the far side where he could not be seen but only scented, nosing here and there as if looking for murre eggs...though much too low for that. For fledglings...though much too early.

Which he certainly knows.

An obligatory charade that abruptly ends in an ambling-lumbering gait which looks like an easy stroll. But isn’t.

The male polar bear, visible in the middle left of this image, roars at the fleeing female and her cubs (lower right). (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The female and her two cubs have almost a hundred meters on him. He wasted time. Now he has to make up for it. He holds close to the cliff where the ground is firm keeping the high ground. Between him and them, a diminishing line of stranded sea ice and the distance they are ahead, which is also...diminishing.

Again she widens her lead. But the cubs cannot keep this pace and she has a decision to make: To fight a male twice her weight, or break, leaving them to save herself.

The polar bear in his stride opens his mouth and roars!

She smashes into the sea.

Spray leaps, her shoulders rising on the pull, and in the confusion of her wake one small, white head, now the other, both being carried into the rip further from her, toward him, the great male roaring, roaring not thirty meters up the beach.

She turns back for them.

[MUSIC: Aine Minogue, “Blessing,” Celtic Pilgrimage, Aine Minogue (Little Miller Music Company), Sounds True Records]

CURWOOD: Writer Mark Seth Lender says that’s a story that ended happily for the cubs. Check out his pictures of this drama at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s trip to the Arctic was made possible by Adventure Canada

- Mark Seth Lender’s website

Coming up...how romantics danced with death in the legendary fogs of London. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Tananas, “Folk Vibe 1,” Amandla! A Revolution In Four-Part Harmony, ATO/BMG]

BirdNote®: Strange Birds from Down Under

Eastern Whipbird (Photo: Brian McCauley)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: We head down-under now – to an exotic, strange, damp world full of unique creatures. Here’s Mary McCann with today’s BirdNote®.

http://birdnote.org/show/australias-rainforest-birds

BirdNote®

Australia’s Rainforest Birds

[http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/193295, 0.02-.05]

The rainforests of Northeastern Australia are isolated from all other rainforests on earth. As a result, they harbor many species of birds found nowhere else.

[http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/193295, 0.02-.05]

The Eastern Whipbird hangs out in the dense understory. It’s dark, crested, 10 inches long – and more often heard than seen. Like its neighbor, the Spotted Catbird, that’s nearly a foot long and emerald-green with white spots.

[http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/202015, 0.37-.42]

Easier to lay eyes on is the large, pigeon-like Wompoo Fruit-Dove, perching high in a tree, gulping down small fruits. Feathered in a stunning combination of green, purple, and yellow, this bird is clearly named for its voice. [http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/202015, 0.37-.38]

While pig-like grunting on the forest floor tells us we’re in the company of the largest bird on the continent – the Southern Cassowary.

Wompoo fruit-dove (Photo: Joe Novella)

http://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Casuarius-casuarius

On average, the female weighs 130 pounds and stands around 5 feet tall, looking like a giant, lush, black hairpiece on thick legs.

http://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Casuarius-casuarius

A helmet called a casque makes it look as much like a dinosaur as any living bird.

http://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Casuarius-casuarius, first recording in list]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Southern Cassowary (Photo: Jan Anne)

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York: Eastern Whipbird [193295] recorded by David A McCartt; Spotted Catbird [189064] recorded by Cedar A Mathers-Winn; Wompoo Fruit-Dove [202015] recorded by Emma I Greig.

Southern Cassowary recorded by Marc Anderson, sourced from

http://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Casuarius-casuarius

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org March 2016 Narrator: Mary McCann

http://birdnote.org/show/australias-rainforest-birds

I’m Mary McCann.

CURWOOD: For photographs of these strange birds from down-under flutter on over to our website, LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Australia’s Rainforest Birds on BirdNote©

- The call of the Eastern Whipbird

- The call of the Wompoo Fruit-Dove

- About the Southern Cassowary

London Fog: The Biography

London Bridge on a foggy day. (Photo: stu mayhew, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[MUSIC – A FOGGY DAY IN LONDON TOWN]

CURWOOD: Rome is the eternal city. Paris is the city of light. And London has fog.

[MUSIC – A FOGGY DAY IN LONDON TOWN, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ek1KFID0gSc]

And it’s not just historical – in just the first week of 2016 London’s air exceeded its annual limit for the toxic gas nitrogen dioxide. But it used to be far, far worse. For days at a time, foul, stagnant, smoky air would settle over the city, turning day into night and sickening thousands. And yet some Londoners had a strange affection for this environmental hazard, and the London fog’s murky shadow was reflected by writers and painters and film-makers. Well, now there’s a new book that examines these legendary “pea-soupers” from writer Christine Corton called “London Fog: The Biography.” And we sent our resident British ex-pat, Helen Palmer, to talk to her.

PALMER: Christine Corton, you're the author of "London Fog: The Biography.” I'm interested into why you decided it should be a biography rather than, say, a history.

CORTON: Because I wanted to see it in terms of it being born and it terms of it being killed off, dying. I wanted to see it having a kind of personality of its own. It was loved by Londoners as well as loathed, and that was why it was called all these names. It was named London Particular in a very affectionate way because Londoners wanted to show how proud they were of it. After all, there is an upside to London Fog - smoke. If you've got smoke in the air, it means you got employment and industry, and it means you can have an open fire to warm yourself. But Londoners were essentially quite proud of it. They felt it created a distinction for them as a city.

Most Londoners heated their homes with coal fires in the 19th century. (Photo: Danny Chapman, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

PALMER: Let's have you read a piece from the book. There's a passage I particularly like on page 245. It's a quotation from The Times from December 1924.

CORTON: Yes. OK.

The London Particular is a true London pride. It is unique, no less than is London gin or London wit. Other places may be able to show a mist or so. Only London has fog. And Londoners are secretly proud of it. Only the largest shareholders in gas and electric light companies, the launderers and perhaps the soap and face cream trades dare to confess their joy in a thorough London Fog, but every Londoner feels, on such a day as yesterday, the distinction of being a citizen of so singular a town. Fog breaks the monotomy of life. It shows itself familiar surroundings in a new and an artificial light. It gives us something to talk about, and those of us who live to see the sensible thing done at last, and the London particular deprived of its artificial foulness, we'll find us ourselves sighing for the good, old days.

PALMER: That's a lovely piece of writing, but in fact, the fog that they're describing was particularly awful. It was full of soot, it was full of - what?

CORTON: Well, it was full of particles basically, from uncombusted coal. So it was very visible. It would turn the color of the fog green, yellow, mainly yellow, black sometimes, but it was very dangerous to breathe in, and people would quite often cough up black spit which showed what they were actually kind of taking in, digesting, and you could suffocate. If your lungs were weak, if you were elderly or very young, you could actually suffocate because you couldn't actually get rid of these rather nasty particles from your lungs.

Claude Monet captured the London fog in a series of impressionist paintings on a visit to the city. (Photo: Musée d'Orsay, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

PALMER: And in fact the fogs did bring much higher mortality when they were really bad.

CORTON: Yes, the 1952 smog which is probably the one most people are aware of, killed possibly about 12,000 people. It’s very difficult to kind of give statistics because, of course, government said well they would've died anyway because they already had lung issues, they had heart issues, or they died from the flu. Quite often governments would blame colds or flu, but nowadays we reckon the '52 smog probably killed about 12,000 people.

PALMER: London's a big city, but still, that's a lot of people.

CORTON: It is, especially when you consider that that’s a week's worth of fog. Of course they didn't die during that week. They may have died two or three months later, but there's no doubt about it. The hospital suddenly had these queues of people who had breathing problems, who had to be put on oxygen, who literally couldn't actually survive breathing the air in.

PALMER: So you talked about uncombusted carbon. This was basically because there was a lot of industry it in London and, of course, everybody had a coal fire. That was how we heated, and that was how we cooked our food.

CORTON: Yes, and people did like their coal fire, and one of the problems with trying to introduce legislation to combat this problem, and, believe me, they did try many, many times from the early 19th century onwards. People kept saying, well, we have no real alternative to our coal fire, and even when they did, they were in love with their coal fire. They liked it being the central, the focal part of their living room.

PALMER: You write about how it inspired so many writers and indeed, artists, particularly artists, and how it appears in both our literature and in our painting in this very romantic light as this very sort of mysterious covering, as this, indeed, this personage in our literature.

CORTON: Yes, it's interesting that almost all writers at one time or another uses London Fog as a metaphor. Dickens is the one we would first of all go to, and he uses London Fog in a variety of ways. In "Bleak House", he uses it as a metaphor for the law. "Our Mutual Friend" it becomes a metaphor for the corruption of the city. Other writers such as Joseph Conrad use it. The artists, that's an interesting story on its own because English artists, such as George Vicat Cole, W.L. Wyllie, they all tried to paint the London atmosphere as it appeared to them, so with a kind of dirty black haze, showing steam powered engines in the distance creating the smog, but in fact, none of these paintings were really acceptable, because most of the industrialists who were buying paintings at that time, they didn't want to see the products of their own industries being kind of portrayed in paint. So, poor old Wyllie, in fact, he painted a wonderful picture in the 1870s, and somebody actually put a knife through it, he disliked it so much. So it's not really until impressionism takes hold. Monet comes over and paints London fog and he paints in this very impressionistic way. You can see the different colors that the fog produces to his eye. He's got purples, he's got green, he's got yellows. You can see that there's an energy behind it which comes across, but interestingly he never actually exhibited these paintings in London. Most of them were sold by foreign buyers, so even in early 20th century, this kind art wasn't really acceptable.

The London fog is a metaphor for the law in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House. (Photo: Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons)

PALMER: You also talk about how deadly the fog was for animals. At the great Smithfield show, this very famous show in London - Smithfield's the meat market - and where they bought all their prize animals, their prize bulls, and the best of the British agricultural product there and the fogs were absolutely deadly for the cattle.

CORTON: Yes, the main one is the 1873 show which there was a weeklong fog outbreak just as the show was opened, and these very well bred, very expensive cattle really suffered. They are seen where they're panting piteously, many of them just die on the spot, they just collapse. In order to try and relieve their pain, they're actually taken outside. But of course, outside is foggy as well, I mean, and the fog was creeping into the Islington insides as well. So about 80 prize cattle died.

PALMER: It's strange. I mean, we're such animal lovers you would've thought that would've galvanized them into action, at least.

CORTON: Well, there were various newspaper reports of how animals in London zoo suffered because of the London fog. Any animal with white fur, such as polar bears, their fur would be covered in these black particles. A, that wasn't very good for them but, B, they of course they would actually try to clean their fur, and buy doing that they would then be taking in even more particles. And in fact, zookeepers said that during foggy days, the animals showed a loss of vitality, they seemed generally depressed, and of course it was argued, well, if this is what's happening to animals in the zoo, can you imagine what is doing to people?

PALMER: Christine, you write about how basically people were constantly getting lost. They couldn't their find way around. Cabbies were getting lost, and even policemen couldn't always find their way around. How did people navigate from A to B if they had to go out in London?

Linklighters lead the way with torches through a London fog, illustrated here in an edition of The Illustrated London News from January 1847. (Photo: Wellcome Images, CC BY)

CORTON: Well, in the 19th century, they used young men, sometimes older men, who would carry links, they were known as linklighters. And they would carry these flaming torches, and promise to lead people back to their homes or to the theatre or whereever. In fact, of course, many of these linklighters were connected to criminal gangs and would often lead the poor unfortunate people up an alley where they would be sandbagged, i.e. hit on the back of a head with a bag of sand, and they would be robbed. But linklighters actually appear in a lot of paintings of foggy days, and you can see them almost causing more trouble than they're worth because they're waving their link torches around, somehow they're burning people's, singeing people's hair. They often kind of drop their torches onto people's feet. So, they're seen as kind of mischief-makers as well as, I say, being tied to crime.

PALMER: It's extraordinary. Giving all these sort of bad things about the fog, why did it really take so long to get it cleaned up?

CORTON: Well, campaigners tried from very early on to clean it up. From the early 19th century, there are people such as a politician called Taylor, Mackinnon in the 1840s. Palmerston had to go in the 1850s. They all tried to bring in smoke abatement acts, but technology isn't there to support these acts, but also it's vested interests. If you're an industrialist and you're trying to make a profit, if you try to improve your chimneys, if you try to clean up the amount of smoke that's going out from the chimney, it's going to cost you money. It means you have to put in new equipment. It means you have to train your stokers to combust the fire quicker, so this is going to cost you money. So of course you're going to be reluctant to an act passed, especially when you yourself as a wealthy industrialist can actually go out and live in the country. You don't have to breathe London's air.

PALMER: And, then, of course, we had interruptions like wars and slumps and the like, and so there were always reasons why this got interrupted.

CORTON: We had the First World War, but after that, of course, then the country was trying to get back on its feet, and, of course, the last thing it wanted to think about was to spend more money on converting people's grates. Then, of course, we have the Second World War. Again in the late 1940s, there's a real effort to produce a really strong Clean Air Act. But the coal industry has been nationalized, and there's a deep suspicion that for the domestic market, the Coal Board is actually supplying a lot of very cheap, dirty coal which is actually producing more smoke, and we're actually sending our more expensive coal abroad because we need the money. So, again, governments are very reluctant to interfere with that. It was really the 1952 smoke that made all the difference.

London’s air is much cleaner than it used to be, but fog and car exhaust still settle into the city now and then. (Photo: Martin Robson, CC BY-SA 2.0)

PALMER: Well, I'm particularly interested in this because I grew up in Worcestershire, and my local MP, Gerald Nabarro, MP for Kidderminster - I grew up three miles from Kidderminster - was the man who in the end that actually got the Clean Air Act on the books.

CORTON: Yes, it is amazing isn't it? I mean, for your listeners who don't really know anything about Gerald Nabarro, he was actually quite a character. He was against joining the European Union. He was a racist. He was actually caught going around the roundabout the wrong way by a policeman who took a photograph, and he said well it wasn't me who went round the roundabout, it was my secretary and the policeman said well she must have a very fine moustache just like yours, because he had this very distinguished handlebar moustache. So, he's not immediately someone that you would actually say was a hero, but in terms of clean air, he was a hero. He decided that he would push the Clean Air Act through, so he took advice from the smoke abatement societies that were around at the time. He actually introduced a ten-point plan. He had a franking machine for his post that said support the clean air act, so he really put a lot of effort behind it.

The only thing was, the government fell, but both Labour and Conservative parties had clean air measures in their manifestos because I think they saw the tide had turned. People were no longer going to accept a London that actually was covered in smoke. That for as many as three weeks out of every year over a period of winter, you would have to walk in pitch black darkness during the day. I think also, post Second World War, people wanted a cleaner, better way of living. They felt they fought a war, and they wanted actually to see positive measures coming from it, and they weren’t prepared to accept what they saw as a very primitive way of living through winter.

PALMER: The fact that it took the fog so long to get cleaned up and the fact that the fog was ultimately, mostly cleaned up due to, well, the insistence of a few people and the changes in technology, do you think this has a lesson for us in terms of addressing global warming now?

Dr. Christine L Corton is a Senior Member of Wolfson College, Cambridge, and a freelance writer. She worked for many years at publishing houses in London. (Photo: William Knight)

CORTON: Yes, I think one of the lessons is to be patient, but also I think you've got to be persistent, not accept government inaction. I think governments can sit on their hands and just hope it will go away, and I think that's the story of London Fog. Governments were very reluctant to pass acts, even the 1956 Clean Air Act. That really happened because of the Nabarro's insistence and forcefulness and the fact that all the newspapers started saying, “This is a killer. This is poison. We have to do something about it.” Macmillan, who was Minister of Housing for the time, was very reluctant to pass the clean air act. And just as we see our ministers today, and I can only talk, obviously, of the London, England, Great Britain situation, they're very reluctant to interfere with the rights of the driver because we all like to use our cars, and yet we don't want to breathe in the pollution that the exhaust fumes produce. So it's a very similar story to coal fires.

CURWOOD: That’s Christine Corton, the author of “London Fog: The Biography.” She spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- London Fog: The Biography

- Read Christine L Corton’s Guardian article: “Beyond the pall … how London fog seeped into fiction”

- About Dr. Christine L Corton

[MUSIC: Abdullah Ibrahim, “Mannenberg,” Amandla! A Revolution In Four-Part Harmony, ATO/BMG]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Peter Boucher, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade/John Jessoe, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - It’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. And Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. And from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth