June 3, 2016

Air Date: June 3, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Coping with Massive Forest Fires

View the page for this story

Fire is natural in the northern boreal forests, but Canadian wildfire expert Mike Flannigan says it has become more prevalent with global warming and puts more communities at risk of massive blazes, like the one that ravaged Fort McMurray in Alberta recently. Flannigan tells host Steve Curwood what communities and homeowners in the midst of fire-prone forests need to do to minimize their risk. (09:40)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra talks to host Steve Curwood about a possible upgrade to the giant panda’s endangered status in China, state officials in Texas trying to hide photos of oil spills caused by recent flooding, the Australian government trying to obscure coral bleaching, and the Arsenic Act of 1851 in England, one of the earliest laws on toxic substances. (04:05)

Climate Change and the National Parks

View the page for this story

The director of the National Parks recently said that climate disruption represents the greatest threat to the integrity of the park system. National Park Service scientist John Gross tells host Steve Curwood how park managers are rethinking many of their management strategies. (08:50)

China Grows More Trees

View the page for this story

After major flooding in 1998, China introduced a national logging ban called the Natural Forest Conservation Program to help protect against erosion and rapid runoff. A recent study in Science Advances of 10 years of satellite data found significant recovery in some Chinese forests. But Andrés Viña, an author of the paper, explains to host Steve Curwood that this reforestation in China is probably shifting deforestation elsewhere. (07:15)

Iron-eating Bacteria

/ Ari DanielView the page for this story

We revisit a report by Ari Daniel, who traveled into the field with microbiologists to report on some strange bacteria that consume iron and may help filter water in the future. (05:45)

Heart of a Lion

View the page for this story

Mountain Lions have been considered extinct in the Eastern U.S. for decades, but one trekked from his home in the Dakotas to just a few miles outside of New York City. Host Steve Curwood talks with author William Stolzenburg, whose new book, Heart of a Lion, carefully documents this creature’s extraordinary two-thousand-mile journey. (11:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Mike Flannigan, John Gross, Andrés Viña, William Stolzenburg

REPORTER: Ari Daniel, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Increasingly hot and dry weather is priming forests for dangerous fires, like the one that ravaged Fort McMurray in Alberta, and that has experts calling for extreme measures to protect communities.

FLANNIGAN: I mean you want a fire guard of at least fifty yards, but in an ideal world you'd like two kilometers, because those burning embers can be carried up to two kilometers by the wind and start a new fire in advance of the head of the wildfire.

CURWOOD: Also, how new genetic analysis can tease out the mysteries of unfamiliar bacteria.

EMERSON: That’s the beauty of these technologies that we we are now able to ask questions that we just never could before. And that’s a really powerful tool for understanding this unseen world that is really a very important world to the functioning of the planet.

CURWOOD: We’ll have that and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, innovating to make the world a better more sustainable place to live.

Coping with Massive Forest Fires

The raging wildfire that a fire chief nicknamed the “Beast” near Fort McMurray May 7, 2016. (Photo: Chris Schwarz/Government of Alberta, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. In terms of dollars, it’s the biggest natural disaster to ever hit Canada. Some $6 billion worth of property went up in smoke as wildfires swept through the City of Fort McMurray in Alberta earlier this year, leaving many homeless. As the immediate threat of the wildfires recedes, those residents lucky enough to still have a home are slowly returning. In this era of global climate change the far north is the fastest warming part, with fires doubling in size over the past fifty years in this region of vast and carbon-rich boreal forests that naturally burn from time to time, and people are rethinking how to protect forest communities like Fort McMurray. For insight we turn now to Mike Flannigan, the Director of the Western Partnership for Wildland Fire Science at the University of Alberta. He joins us from Edmonton. Welcome to Living on Earth.

FLANNIGAN: Oh, glad to join you.

CURWOOD: Now the wildfires that overtook Fort McMurray in early May were particularly devastating. Why?

FLANNIGAN: Well, there are three ingredients for a forest fire to occur. You need fuel, the stuff that burns, the dead organic tree on the forest floor - needles, leaves, the shrubs, the trees. How much fuel you have, how dried it is really important. The second ingredient is ignition and people and lightning are the two common ignition agents. The third reason is the weather—hot, dry, windy, we call it. So you need all three to come together and that's exactly what happened this spring at Fort McMurray. We have lots of fuel in the boreal forest. We had an ignition that's still under investigation. I'm 99 percent sure it's human-caused because of the time or year and the location, the proximity. And we had hot dry windy weather.

Mike Flannigan is a professor in the Department of Renewable Resources and Director of the Western Partnership for Wildland Fire Science, both at the University of Alberta. (Photo: University of Alberta)

CURWOOD: So, Mike, how is climate change making North American forests more vulnerable to fire?

FLANNIGAN: Well, in Canada our average annual area burned used to be one million hectares per year in the early ’70s. It is now two million hectares per year and we believe this is due to human-caused climate change, and in particular the temperature. I get asked all time, why temperature? Well, three reasons: first the fire season is longer, the warmer we get. In Alberta, our fire season officially started this year on March 1, it used to be April 1. Second, the warmer it is, the more lightning you get. The more lightning you get, the more fires you get. Third, probably the most important: as we warm the atmosphere's ability to hold moisture increases almost exponentially. What this means is the atmosphere is more effective at sucking the moisture out of the fuel, and projections of the future say we're going to warm but we’re not going to get that much more precipitation. Bottom-line, dry air, fuels, easier for fires to start to spread.

CURWOOD: So what could communities like Fort McMurray that are surrounded by forests do differently to prepare for large wildfires if these are to be coming again and again and again? What's to be done?

FLANNIGAN: Well, we go back to the three ingredients. We cannot do anything about the weather, we cannot do it about lightning. We can do things about human-caused fires and fire management agencies do a recently good job - prevention, education, firebands, fire restrictions - but I think the biggest gains can be made by managing fuels around communities, reducing the amount of fuel, the type of fuel. Conifers are very flammable, so you want to remove conifers around communities. If you have trees, have deciduous trees or have grass, you can have sprinklers. Don't have things like wood shingles on your roof, pine needles in the eave troughs, wood decking, shrubs beside your house, firewood stacked by your house. I was on the Slave Lake fire shortly after the fire and fire is opportunistic. It likes to find a pathway. It's looking for a wick. And there was one house that unfortunately burned down, and it had mulch along the sides of the driveway. The fire burned the mulch right up to the house and then burned the house, so you got to think how can the fire find its way to my house and how can I stop this. There's programs in Canada, and in the United States. The United States is called Fire Wise. Canada it’s called Fire Smart. There's guidelines and suggestions for homeowners and for communities to reduce the risk of fire.

A firefighter hoses down hotspots near Fort McMurray May 6, 2016. (Photo: Chris Schwarz/Government of Alberta, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, essentially we are talking about fire breaks, fire lines. What would've protected Fort McMurray? How far back would you have to cut the forest in order to have avoided disaster in Fort McMurray?

FLANNIGAN: Well, let's put it in context. Fort McMurray I would classify as medium risk. There are communities across boreal forest that are much higher risk because they have more conifers around them. There's a lot of deciduous trees around Fort McMurray, but to answer your question, I mean you want to fireguard at least 50 yards, and what that does is it allows fire management crews to put the fire out because if you remove the fuels it will be lower intensity and they can deal with the fire. High intensity, you can't use firefighters on the ground because it's not safe and an aerial attack becomes ineffective. In an ideal world, you'd like two kilometers. You say why two kilometers? It's because, and maybe some of your listeners seeing some of the video from Fort McMurray saw this rain of burning embers, those burning embers can be carried up to two kilometers by the wind and start a new fire in advance of the head of the wildfire.

CURWOOD: In other words if you want your town to be completely safe in the boreal forest, you need to be little more than a mile away from big forest.

FLANNIGAN: Yeah and even then I would say it greatly reduces the risk but it would still not eliminate the risk unless you've had cement or pavement or bare ground or something because even if you had grass and sprinklers, grass does burn under the right conditions. Fuel is fuel is fuel, we say when the weather is severe and one of the characteristics about fire is that in western United States, one percent of fires are responsible for 99 percent of area burned. In Canada, 3 percent of of the fires are responsible for 97 percent of the area burned. So, what happens is most of the fires, the big fires, occur on a few critical days of hot, dry, windy weather. Fire management agencies are very effective at putting out fires under most conditions except under the extreme conditions, but those are the times when we have the largest impact and the biggest area burns.

Premier of Alberta Rachel Notley and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited Fort McMurray on May 13th, 2016 in the wake of the wildfire that ravaged the city. (Photo: Chris Schwarz/Government of Alberta, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So in other words, the fire army can handle most assailants, but when Godzilla comes, it is a problem.

FLANNIGAN: And it's a big problem, yes. It's a monster. Now, a curious thing about this particular fire is that it developed a pryocumulonimbus, pyro CBs we call them. It developed its own thunderstorm, and this thunderstorm actually generated lightning which we've seen before, but these lightning strikes from this particular pryocumulonimbus started new forest fires because the forest fuels were so dry and that's the first time I’ve seen the lightning from a fire thunderstorm start new fires.

CURWOOD: So we're talking about a new meaning to firestorm.

FLANNIGAN: Yes, self-perpetuating, self-regenerating firestorm. Yes.

CURWOOD: Hey, what's the difference in terms of forest management policies between the US and Canada?

FLANNIGAN: Well, both countries have modern fire management agencies. They're very effective at what they do, but both countries have changed their thinking recently and a catalyst for change in the United States was probably the Yellowstone fires. When they happened in 1988, at the time many people considered it a disaster, that a huge chunk of Yellowstone National Park burned down, and the reality is, it's part of ecology of the forest. Trees in the boreal western United States, they're used to regular stand-replacing, stand-renewing fires. Fire management in the United States and Canada has moved away from the full suppression model. It used to be, you put out all the fires, all the time. Now we have something called appropriate response, and when a fire starts they determine if it's an unwanted or dangerous fire, and if so, they hit hard, they hit fast. However, if a fire occurs in the wilderness, we run fire growth models for the next week or two, and say, “where will that fire spread?” If it's not spreading towards communities then we say, “we'll monitor this fire and let Mother Nature do her job.” So this is the new reality we have to live with fire, coexist with fire because we cannot completely eliminate it. We've tried to eliminate fire and it doesn't work.

The fire that devastated much of Fort McMurray, seen here on the evening of May 4th, 2016, was so massive that it created its own weather in the form of towering “pyrocumulonimbus” clouds capable of generating lightning. (Photo: Chris Schwarz/Government of Alberta, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Mike, you're an expert on wildfires. What drew you to this field?

FLANNIGAN: Well, I have two loves in terms of science, weather and fire. So when I was one, at my birthday I had a candle on my cake. I stuck my finger in that candle and forgot to remove it, OK?

[LAUGHS]

FLANNIGAN: And they have a picture of me crying, and they did eventually let me move my finger away, but I was just sitting there with my finger because I was fascinated by flame. Right from day one I've always been interested in fire, and I've always been interested in weather. People used to ask me what I would be when I grew up. A weatherman. Big snowstorm big thunderstorms, too excited to sleep. I'd stay up and watch the storm all night, so I'm very fortunate. I get to study fire and weather. It's great.

CURWOOD: Mike Flannigan teaches at the University of Alberta and directs the university's western partnership for wildland fire signs. Mike, thanks for taking the time with us today.

FLANNIGAN: Oh my pleasure.

Related links:

- CNN: “Alberta wildfire: ‘Welcome home Fort McMurray’”

- Fort McMurray wildfire status

- Reuters: “Canadian oil producers warn of supply shortfalls after wildfire”

- The Guardian: “Spike in Alaska wildfires is worsening global warming, US says”

- About Mike Flannigan

Beyond the Headlines

Conservation experts are considering upgrading the status of the giant panda in China from 'endangered' to 'vulnerable.'. (Photo: Gill Penney, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time to check in with Peter Dykstra now. Peter is with DailyClimate dot org and Environmental Health News, ehn dot org and he’s on the line from Conyers, Georgia to tell us about the news beyond the headlines. How are you doing, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. I’m doing pretty well, and I’m going to start with some good news – possibly good news – from China. The giant panda may get an endangered species upgrade, thanks to improved habitat and a reported 17 percent increase in wild panda populations over the last 13 years.

CURWOOD: Well, now that would be some great news, but, uh, unless it’s too good to be true.

DYKSTRA: Well, you’re right to be skeptical, and you may recall a couple weeks ago we discussed similarly good-sounding news about Asian tiger populations, but that info was almost immediately called into some question. As for the pandas, there’s no doubt that China has put a lot of effort into protecting its national symbol.

CURWOOD: So, whose report is this?

DYKSTRA: It is the Chinese government’s report, but the International Union for the Conservation of Nature is reportedly looking into it, and if they confirm China’s good news, they could list the Giant Panda as a “vulnerable” species, which sounds pretty bad, but it’s actually an improvement from an “endangered” species.

There’s one caveat here – the last time the IUCN took a long look at panda populations was in 2008 and back then, their view was more pessimistic than that of the Chinese government.

CURWOOD: Hmmm, so we’ll see. Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, you know some governments blast out the good news...

CURWOOD: Or POSSIBLE good news.

DYKSTRA: Right, and other governments focus on burying the bad news. For the second straight month, Texas is coping with major flooding from heavy rain. In April, the Civil Air Patrol, a volunteer group affiliated with the US Air Force that aids in disasters, took a ton of photos showing apparent oil spills from flooded tank farms and from fracking sites. The pictures were posted at a University of Texas web site, at least until state officials ordered them taken down, effectively hiding the spill images from public view. Except a reporter for the El Paso Times wrote about the apparent censorship and published the pictures, leaving yet another oily stain on the reputations of Texas environmental officials.

Flooding in Texas may have caused the release of oil from fracking and well sites. (Photo: Todd Dwyer, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yah, it’s amazing how often attempts to cover something up bring more attention to the problem than ever.

DYKSTRA: Well, I’ve got another example of that for you. There’s been a lot in the news lately about the imperiled Great Barrier Reef, with widespread reports on bleaching and dying coral. But the Great Barrier Reef is a tourism gold mine for Australia. And you know, who would want to go diving on a dying reef?

So when a UN report on the threats posed to World Heritage sites by climate change came out last week, the Australian Government asked the UN to yank the chapter on the reef. And the UN said “okay.” All reminiscent to me of one of my favorite symbols of denial in movie history, the mayor from the movie “Jaws.” ‘THERE’S no shark problem here on Amity Island!’ And just like in “Jaws,” high profile mayhem ensued.

CURWOOD: So it’s possible that this one chapter of a UN report got more attention by getting censored than it would have gotten if it were published.

DYKSTRA: Exactly.

CURWOOD: Hm. Hey what do you have from the history vault for us this week?

DYKSTRA: A hundred sixty-five years ago this week, the British Parliament passed one of the earliest laws on toxic substances in the world. The Arsenic Act of 1851 required arsenic sellers to keep records of each sale and obtain some assurance that the arsenic would be used properly.

One hundred sixty-five years ago this week, the British Parliament passed the Arsenic Act of 1851, one of the earliest laws on toxic substances in the world. (Photo: James Laing, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Which begs the question, just what are the proper uses of something as toxic as arsenic?

DYKSTRA: Well, mostly things that wouldn’t be considered proper, or even legal, today: in cosmetics, and agriculture, and even in medicines. Arsenic was also used for centuries for some decidedly improper purposes by emperors, popes and noblemen to eliminate their rivals.

CURWOOD: Well maybe the Arsenic Act of 1851 helped Queen Victoria to stick around so long.

DYKSTRA: Sixty-four years on the throne.

CURWOOD: Well, actually, our resident Brit here corrects me. It’s 63 years, 7 months – and now Victoria is surpassed by Queen Elizabeth 2, her great great granddaughter. I think that’s as of September 9th in 2015.

DYKSTRA: I stand corrected. My apologies to her royal majesties.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org, and dailyclimate.org. Thanks, Peter. We’ll talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: Thank you, Steve. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- China says Pandas bouncing back

- IUCN to assess Panda populations

- El Paso Times editorial on flood-related oil spills: “Hiding bad news from Texas”

- El Paso Times news story, with spill photos censored by the State gov’t.

- About the Arsenic Act

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from Wunder Capital, an online investment platform that allows individuals to invest in solar projects across the U.S. More information and account creation at Wunder Capital.com. That's Wunder with a 'U'. Wunder Capital, Do well and do good.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Wendy Rolfe/Deborah DeWolf Emery/et al, “1, 2, 3, 4,” Images of Eve, I-Yun Chung, Odyssey Discs]

Climate Change and the National Parks

Sea-level rise is a major threat to coastal parks including Everglades National Park (Photo: Erik Salard, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. Climate change is not just incinerating boreal forests – it’s also presenting new challenges to one of America’s most beloved icons - the National Parks. Indeed, park service director John Jarvis recently said climate disruption represents the single greatest threat to the integrity of the parks that we have ever experienced. And this is causing a wholesale rethink of planning for the future of the parks. John Gross is an ecologist busy at work as part of the National Parks Service’s Climate Change Response Program, and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, John.

GROSS: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, tell me what kinds of impacts of global warming immediately come to mind in our national parks?

GROSS: Well, we're seeing all kinds of climate change impacts throughout the system, so some of the most obvious, for example, are sea level rise impacts on coastal parks where we're seeing erosion of cultural resources, of beaches and these sorts of things. In our parks in the northern areas, for example, in Alaska, we're also seeing melting of permafrost, park staff are having a very difficult time getting into some parks because they need either the lakes to be thawed and have no ice on them or else to be sufficiently frozen that they can land airplanes, but now they're seeing longer seasons of slush on the lakes and you can't land an airplane on slush. In addition to that, parks are seeing the kind of impacts that the forests are. We're seeing increasing fires that are more severe and larger. In many of our western parks you'll see a lot of trees that are affected by pine beetle and are brown, and those occur in Rocky Mount National Park, for example. We have extensive tree death up in Yellowstone with white bark pine and other species. The seasonality of things are changing. So park visitors are actually responding to climate change also and they're showing up earlier in parks, and in some cases staying later. So the impacts are really extremely widespread all over the parks.

The USGS is studying the impacts of climate change in Glacier National Park in Montana (Photo: United States Geologic Survey)

CURWOOD: So how's the Park Service responding?

GROSS: The Park Service is responding in a variety of different ways. Initially when we started, our primary means was to educate people in the parks and to increase our interpretation of climate change impacts that were being seen on the ground. So that's training park managers as well as those of us that service many parks. We’re doing a lot of mitigation efforts using hybrid cars solar voltaic arrays to produce solar electricity for parks, reducing our environment footprint. So there’s a whole series of responses from on the ground all the way up through training and working with staff.

CURWOOD: How's it changing the management of the parks service now that you're thinking a lot about climate change?

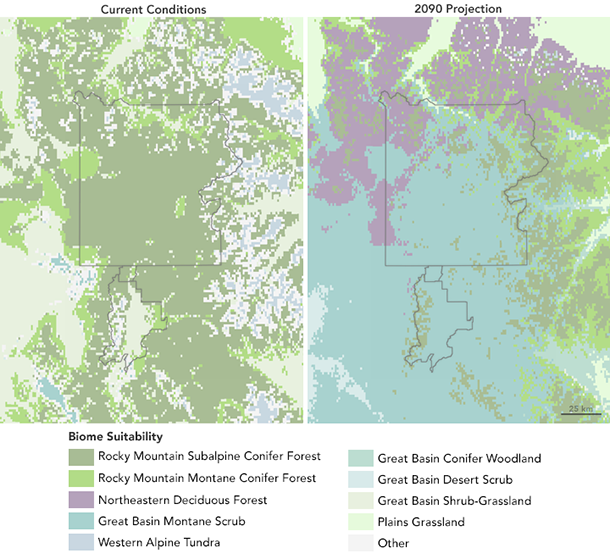

GROSS: Well, we're really changing the way that we're looking at planning. So in the past, our planning was designed to identify, for example, one desired future and we now recognize that there's a broad range of climate projections and that doesn't work, and so we're trying to develop scenarios for our parks where we look at two or three or four different possible and plausible futures, based on scientific projections of climate, and then we use those to try to find strategies that are robust. We recently released a report called "Revisiting Leopold" that carefully examined our management strategies, and their first recommendation was that the overarching goal of the park service should be to steward resources for continuous change.

Now, that's a dramatic departure from the past where the previous Leopold talked about maintaining vignettes of the American wilderness, which essentially was before European occupation. So we've recognized that the fundamental underpinnings of the way that we manage parks has to change with climate change, that it's no longer trying to maintain a system as it was 100 years ago. That's just not possible, so we're looking much more towards broad-scale effects and allowing species to move into and out of parks to adapt to climate changes.

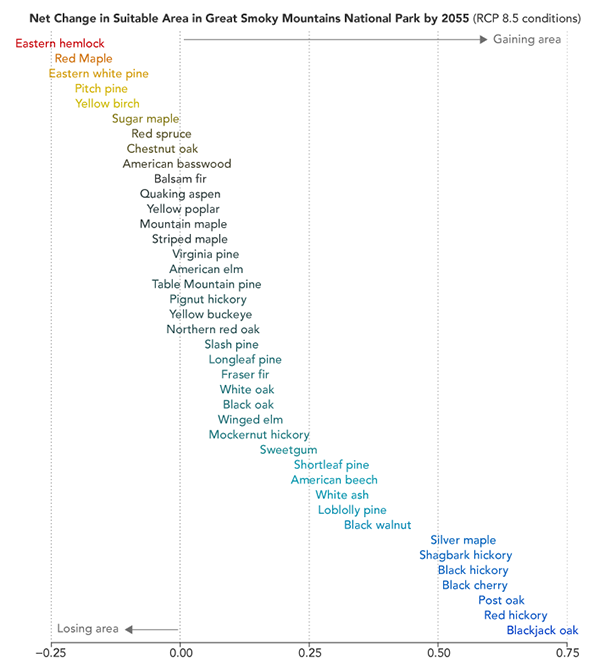

Climate change will affect each species differently. While warmer conditions are undesirable for some trees, they are more desirable to others. Over time, forest compositions will change as saplings slowly migrate with the changing conditions. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory chart by Joshua Stevens, using data from the Landscape Climate Change Vulnerability Project

CURWOOD: Yeah, back in the day there was something of an attitude among conservationists that, you know, just put a big fence around this big plot of land, protect it from development, but of course climate change doesn't pay attention to any kind of fence.

GROSS: No, it doesn't and that's really one of the biggest challenges that we face, that our park boundaries or not changing, but now climate change is happening so rapidly that animals need to move, they can't adapt to the climate change in place, and so those areas that are suitable for species are moving, but the park boundaries are not and that's why we’re looking so much at connectivity of parks and working much more with their neighbors through the landscape conservation cooperatives, trying to recognize the park served essentially isolated and so we need to increase the conductivity between parks and the surrounding landscapes so animals are able to move. We've got the Yellowstone to Yukon initiative, there're some major migratory corridors from pronghorn and mule deer that inhabit the area around Great Teton and Yellowstone National Park, and they migrate to the south towards the Red Desert. And it's not just western parks I was recently at the C & O canal, and the C & O canal was a very important linking landscape between a whole series of state forests and other natural areas along the Potomac River near Washington DC. So these corridors and conductivity between natural habits extremely are important all throughout the United States and the rest of the world.

The Pine Bark Beetle is one of the major threats to Western forests (Photo: Simon Fraser University, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: You know, animals of course have wings, they have legs, they can move to other locations. Trees move a lot less rapidly, generally a seed can move a little bit more in a generation and then move a little bit more. So, how's climate change affecting the composition of trees within our national forests?

GROSS: Well, we're already seeing some changes. There was a study that was just published from California that showed that in the Sierras there's a number of tree species that are moving up the mountains, moving up in elevation as it gets warmer. The climate models are projecting that the areas where trees live now are going to change dramatically. Some of them, it turns out have been there for thousands and thousands of years and they're likely to be less affected, but a lot of the dominant tree species will be strongly affected by climate change. These changes are unlikely to be gradual changes, that what we'll see is that mature trees are generally pretty resistant to climate and they'll stay there until there's a big fire or some other disturbance that kills a large area. So we're very concerned about when that happens the tree species that are probably suitable for that area are not likely to be there, and so there won't be seed sources. So we're looking right now to try to project what kind of species might occur and be thinking about do we need to provide corridors via prescribed burns or other methods that might facilitate these movements of species.

The warming world is changing when wildflowers bloom in National Parks like Mt. Rainier in Washington State (Photo: Jim Culp, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, sea level rise could be a serious challenge for some of our national parks. I'm thinking of the Assateague Island National Seashore Area where all those ponies on that island are. Of course, the Everglades are right at sea level. What's the planning at the Park Service about those places?

GROSS: Well, they're changing quite a bit. With Assateague, for example, traditionally we had firm structures that were on the shorelines there, and for now, what we've done is we've for example are paving roads was crushed corals in other areas rather than something like asphalt so we know that as sea level rises those facilities will either be destroyed or need to be moved. So we also have portable buildings that we can move. In terms of the land itself, we're recognizing that some of those beaches and some of those dunes are not going to exist in the future. Similarly, with Everglades most of that park is extremely close to sea level and the projections of sea level rise are that the area of that park is going to decline dramatically. Right now, we don't have any plans in place to reduce the area of the park or change the boundaries for example, but it is affecting in a fairly substantial way, our planning for facilities and so we're not siting facilities in areas that are projected to be under water in the next four, five decades.

Climate change can make an area less suitable for some trees and plants—and more suitable for others. Within several decades, the primary vegetation found around Yellowstone is predicted to undergo substantial transformation. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory map by Joshua Stevens, using data from the Landscape Climate Change Vulnerability Project)

CURWOOD: The National Parks about 100 years old. If you were to look ahead another century, what role do you see National Parks playing over the next hundred years while we are trying to preserve biological diversity at a time of rapid change, climate change?

GROSS: I think the parks absolutely have a critical role to play in that, in a variety of different ways. We have on the order of 400 million visitors per year, and so I think the parks are really a very important educational role for people to tell them about climate change, to interpret the changes that we're seeing now. They also have an extremely important role for preserving biodiversity. We have some of the finest landscapes in the world in our national parks and so I think the parks will continue to play all of the roles that they play now in terms of sites that people want to visit for aesthetic or recreational reasons, for preserving biodiversity and for educating people from around the world on what's happening with their natural environments.

CURWOOD: John Gross is an ecologist with the National Park Service's Climate Change Response Program. Thanks for joining us, John.

GROSS: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Read more about how climate change is impacting trees in National Parks

- National Parks Service Climate Change Response Program

- It’s the 100th anniversary of the National Park System

- Landscape Climate Change Vulnerability Project

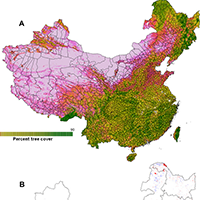

China Grows More Trees

Satellites tracked forest cover and regrowth from 2000-2010 in the study, “Effects of conservation policy on China’s forest recovery,” published in Science Advances. (Photo: Viña et al. Sci. Adv. 2016)

CURWOOD: In 1998, China endured heavy rains and devastating floods that killed thousands of people and evoked memories of the 1931 floods that had killed millions. And even as the 1998 waters were still receding, the Chinese government announced it would outlaw the clear cutting of forests, and restore lakes and wetlands since trees and swamps can help soak up rainwater and reduce the risk of flooding. China also began its “Grain for Green” program paying farmers to prevent erosion and reforest hillside terraces. Professor Andrés Viña of Michigan State University has been following China’s afforestation program by studying 10 years of satellite images. He is co-author of a paper on the subject in "Science Advances". He joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Prof. Viña.

VIÑA: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So what was the basic premise of your study? What did you set out to answer?

VIÑA: Well, after the floods of 1998 in China, the Chinese government decided to implement a series of forest conservation policies in order not to just protect the forests that they had, but also increase the amount of forests, particularly in the mountain regions in order to try to prevent the floods of 1998 to happen again. So they implemented two national programs, one was the Grain to Green program, which is basically to reconvert agricultural fields in steep slopes into forests and the other is the natural forest conservation program which is, in a sense, a logging ban to prevent deforestation and also to increase the aerial forests. At regional scales in the Szechwan province the program seems to be working in the sense that there is forest regeneration, forest recovery. And so we wanted to see if that was the case on a national scale, and we also wanted to see if the program was, in fact, related with this regeneration.

China’s conservation policies banned logging and employed locals as park rangers, protecting forests so that they could regrow. The recovery of a forest in the Min Mountains, Sichuan Province, is pictured here. (Photo: Andrés Viña)

CURWOOD: So, how much recovery did you see?

VIÑA: What we found was that, in fact, the areas of the forest had regrowth over the last 10, 15 years, and that the program was in fact related with this regrowth. I can tell you that it's about 1.6 percent of China has exceeded a net gain in forest cover. A big chunk of the gains were in Central China and that amounted to about 61,000 square miles, but there was also some places where there were losses, particularly in the northeastern part of China in the Heilongjiang Province. A big chunk of those were because of fires but that amounted to about 14,400 square miles of loss, for a net gain of about 46,000 square miles.

CURWOOD: Now, you said that some of these gains in the reforestation came from the conversion of steep hillside cropland into forest. How were peasants encouraged to give up that little plot of land even when it's on steep hillside?

VIÑA: You have to remember that this is China, so the land is not owned by the farmers. But there is an actual compensation; the Green to Grain program originally started by giving the farmers seeds, but then it turned into an economic payment in which they actually get compensation for the land that is being planted into trees. And in the case of the Natural Forest Conservation program, the places that we evaluated paid local people to go on and monitor that there is no illegal harvesting of the trees. In essence, these two programs are payment for ecosystem services programs.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the factors in addition to the Natural Forest Conservation program that allowed the forest to grow.

VIÑA: There has been a lot of economic development in China for the last 25 years. The Chinese government claimed that 40 million people came out of poverty within the last 25, 30 years, so there has been certain big economic development in the country at the same time that these programs were implemented. Basically there was a lot of migration, rural to urban migration, and there is a reduction in the pressure of forests. And at the same time, there is an increase in the tourist environment, to spend more money in protecting the environment etc. There's more political will because there are more affluent people.

Forest recovery was seen particularly in mountain regions, including the Min Mountains pictured here, and in areas that had previously been cut down by logging companies. (Photo: Andrés Viña)

CURWOOD: What about the economics of the people who did this conversion? To what extent did people lose jobs, gain jobs?

VIÑA: There were many state owned companies doing the logging of the trees, and stopped working, stopped operating because of all the implementation of these programs. So, naturally, a lot of people were left unemployed and many of those were absorbed by the urban centers.

CURWOOD: What message to the rest of the world does this program's success offer? I'm just thinking of the recent international climate agreements. How can this help the global climate? How can this encourage other folks to follow China's path?

VIÑA: The Natural Forest Conservation Program is one of the biggest of environmental programs in the world in terms of the amount of money involved. It's about $93 billion yuan. In terms of applying a massive program as this for the developing world it's, I would say, very expensive. One has to come up with the money.

CURWOOD: Some say that China's success with forest regrowth may come with the cost of deforestation elsewhere. Tell us more about that.

VIÑA: China has become one of the leading timber importers in the world. What we believe is that this is leading to deforestation elsewhere. Where that elsewhere is, well, it's Southeast Asia, Vietnam, Indonesia, as well as Africa, Northern Eurasia, Russia are the ones that are now supplying all the gap that has been left by this program enacted. In a sense, the program exported the deforestation, and we basically also speculate that it's not just a climate issue but also a biodiversity issue because many of the places that are being deforested right now are also places of high biodiversity. We are replacing high biodiversity places and in other places for relatively poor biodiversity forests in China.

CURWOOD: So, going backwards in a quest to protect by diversity, you're saying.

VIÑA: Basically that's what we think the trend is.

CURWOOD: So how does one connect the dots here? If forest conservation in China means more deforestation elsewhere on the planet, how can scientists and countries communicate so there is a net gain?

VIÑA: I would think the only way is that we as consumers with user consumption habits and user consumption rates basically encourage China to participate in things like sustainable timber production certification. A lot of that timber that is imported it’s used to produce furniture, for example. But then is exported again to countries like the U.S. and countries in Europe, etc. So, indirectly, we are contributing to this export of deforestation. The world is globalized. What we do in one place will have repercussions beyond that particular place.

CURWOOD: In other words at the end of the day, the world is just one giant ecosystem.

VIÑA: Exactly.

CURWOOD: How do you feel about your research? Encouraged by what you see? Not so encouraged?

VIÑA: Thinking of China as a vacuum, it's a win for China, but how much a reality in terms of climate change mitigation this program is accruing is still a question mark. We believe that China is exporting deforestation so overall there is a net loss, but we don't know how much it is.

CURWOOD: Andrés Viña is an assistant professor at Michigan State University attached to the Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

VIÑA: Thank you for having me today.

Related links:

- The study as published in Science Advances

- Overview of the study from Michigan State University

- Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability at Michigan State University (MSU)

[MUSIC: The Hubei Song and Dance Ensemble of the People’s Republic of China, “Concert of the Eight Tones,” The Imperial Bells of China, Fortuna Records]

CURWOOD: The cat came back...the astonishing journey of a mountain lion from South Dakota to a bedroom town just outside New York City. That’s ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mike Wofford, “Little Girl Blue,” Mike Wofford At Maybeck (Maybeck Recital Hall Series, Volume Eighteen), Richard Rodgers/Lorenz Hart, Concord Records]

Iron-eating Bacteria

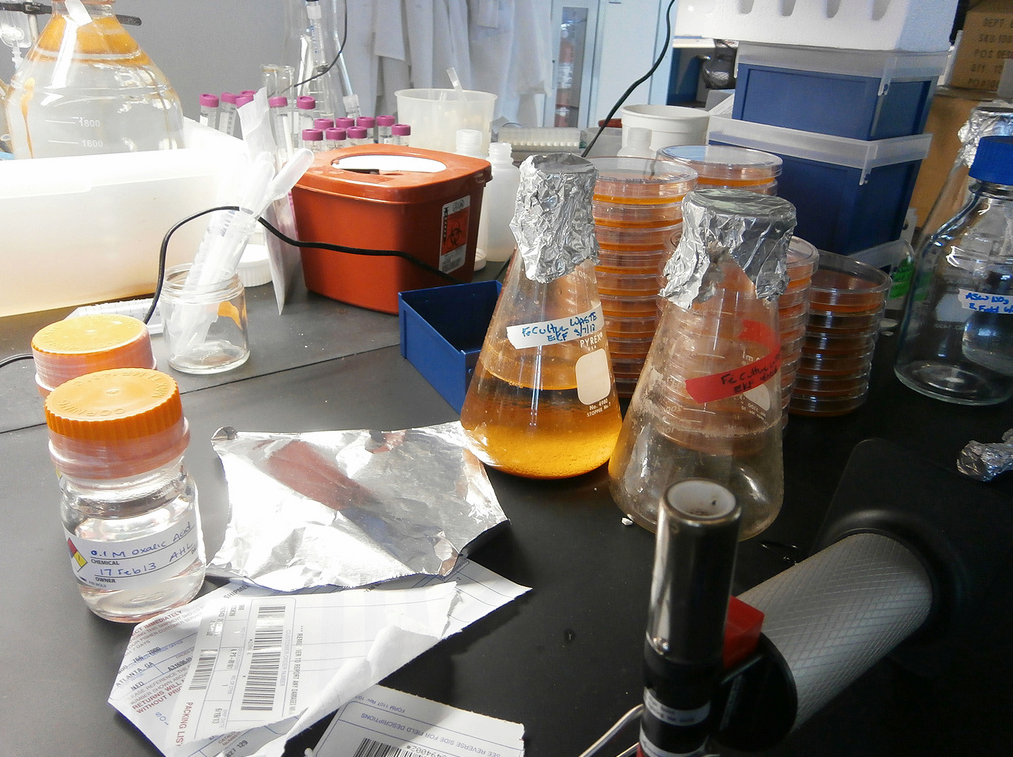

Bright Rust and Iron-oxidizing Bacteria (Ari Daniel)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. In the quest to mend the ecological damage and imbalances humans are causing, many enterprising scientists are turning to the endlessly inventive natural world - for example bacteria that can metabolize oil spilled into the sea, or plants that take up toxic compounds. And such amazing life forms are everywhere. Reporter Ari Daniel discovered some scientists who are wading into a rust-colored ditch in Maine to find a whole ecosystem of unusual life forms.

DANIEL: When you think of life on Earth, plants and animals probably spring to mind. But there are species so odd – so unexpected that you’d never even dream them up. And yet, they’re often thriving in the most ordinary of places.

[CAR DOORS CLOSE]

DANIEL: David Emerson parks his car at Ocean Point in Boothbay, Maine, and we hop out.

DANIEL on tape: So it’s kind of picturesque, and we’re on the side of the road standing next to kind of a ditch.

EMERSON: Exactly.

DANIEL: You brought me to a ditch.

David Emerson and microbiologists sampling iron-oxidizing bacteria (Photo: Ari Daniel)

EMERSON: I brought you to a ditch! But it’s a unique ditch.

DANIEL: The ditch is filled with water the color of bright rust.

EMERSON: It looks like just rust and goo, and it is in a sense, but, I mean, this is all bacterial.

DANIEL: Ditches like this one are right up Emerson’s alley – he’s a microbiologist at the nearby Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences. And he studies the bacteria that produce this rusty goo.

EMERSON: So we’re primarily looking in this site at an organism called Leptothrix ochracea.

DANIEL: It’s a kind of iron-oxidizing bacteria, and these microbes have been pulling off an incredible feat for the last two to three billion years. They survive by feeding on the iron dissolved in particular water flows. It’s something that’s incredibly hard to do, because iron has so little energy.

EMERSON: And so that’s one of the reasons they’re interesting to us, is finding the most minimal amount of energy that an organism can use to survive.

DANIEL: Most people familiar with these bacteria, though, are not impressed. They tend to be annoyed.

EMERSON: Yeah, so I mean, these organisms are pretty heavily involved in fouling and corrosion of water pipelines.

DANIEL: There have been episodes when people turned on their taps and orange water gushed out.

Microbiologist David Emerson’s lab (Photo: Ari Daniel)

EMERSON: The entire system had gotten clogged with iron bacteria.

DANIEL: But they’re not all bad. Once the bacteria feed on the iron, it turns to rust, and that rust can grab onto stuff floating by – like arsenic, other harmful metals, even viruses. In other words, these bacteria can actually help filter water. And that rust – it’s remarkably delicate.

FIELD: I do find it beautiful. OK, if we bend over right here...

DANIEL: Erin Field – a microbiologist in Emerson’s lab – crouches down on one side of the ditch.

FIELD: We have this nice, fluffy matte. Like if you pulled out part of a pillow, it kinda reminds me of that. But then, you see within it, we have this really dark orange, almost looks like crumble topping, kinda like on a coffee cake.

DANIEL: So, in other words, in this ditch, we’re looking at an incredibly complicated ecosystem.

FIELD: Yes, we really are.

DANIEL: Another microbiologist – Emily Fleming – walks over to the ditch.

FLEMING: What makes them special for me is that when you look at them under the microscope, they make these amazing structures of either tubes or twisted stalks.

DANIEL: Fleming says that until recently, these bacteria were impossible to grow in the lab. It turns out that a ditch is a surprisingly complicated thing. So most of what we know about the bacteria dates back to the 1830s when they were first discovered.

FLEMING: So this leaves a huge area for us to be able to explore. It’s a mystery right in front of our eyes.

DANIEL: Recently microbiologists have figured out how to grow a handful of these bacteria species outside their natural habitat.

Microbiologist David Emerson (Photo: Ari Daniel)

[LAB NOISE]

DANIEL: Back in his lab, Emerson is surrounded by vials and petri dishes, each one containing a small rusty sunset.

EMERSON: And so you can see all the rusty goodness, we call it.

DANIEL: Some of these bacteria belong to the genus Gallionella – they were collected from that ditch in the springtime. Emerson’s also got a handful of Zetaproteobacteria species that he discovered on the seafloor near Hawaii. He feeds his bacteria steel dust and makes sure they get just enough oxygen. The result is a lot of happy microbes. But there are still many species that refuse to grow in the lab. And there are basic features of all these bacteria that Emerson and his team just don’t understand. Like how exactly they feed on iron. Or what things all these bacteria have in common. And this is where a relatively new technique comes in – something that Bigelow Lab is becoming expert at. Sequencing the DNA from a single cell. Heres’s Erin Field again.

FIELD: It’s a really cool technique because it’s the only one currently where we can get DNA, and directly link it to a specific cell.

DANIEL: In the past, scientists needed lots of cells to get enough DNA. Now they need just one to spool out and read off the contents of an entire genome. Emerson says the technique’s being applied to all sorts of microbes that are difficult to grow in the lab.

EMERSON: That’s the beauty of these technologies that we are now able to ask questions that we just never could before. And that’s a really powerful tool for understanding this unseen world that is really a very important world to the functioning of the planet.

DANIEL: Emerson says it’s just a matter of time before we figure out how to harness these bacteria to improve our world – by filtering water, building mini-structures out of rust, and catalyzing reactions. Not bad for a group of bacteria dining on iron in a roadside ditch. I'm Ari Daniel.

CURWOOD: Our story on iron-oxidizing bacteria is part of the series, One Species at a Time, produced by Atlantic Public Media, with help from the Encyclopedia of Life.

Related link:

Follow David Emerson’s research

[MUSIC: Matt Haimovitz/Christopher O’Riley, “Weird Fishes/Arpeggi,” Shuffle. Play. Listen., Radiohead/arr.Christopher O’Riley, Oxingale Records.]

Heart of a Lion

Mountain lions used to live from coast to coast across the continental U.S., but are now absent from the East Coast except for a few rare males passing through. (Photo: wplynn, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And now for an adventure story, a true animal adventure story. As urbanization has advanced across the US, so wild animals have been in retreat. Yet just a few years ago a mountain lion ended up in Connecticut near New York City, where none had been spotted in a century. Cougars still inhabit the American West, especially in the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming, but it’s a journey of thousands of miles to reach the East Coast, and fraught with peril. Wildlife ecology writer William Stolzenburg tracks the unlikely journey of this big cat in his new book "Heart of A Lion". Welcome to Living On Earth.

STOLZENBURG: Thanks, Steve.

CURWOOD: This is a fascinating book. For years, and I mean many, many, years there's been rumors of mountain lions in the east, and your book, of course, is about this journey of one. So, tell us about this particular wandering lion. Where did he come from, what was he like, and what made his journey unique?

STOLZENBURG: Well, yeah, SO in June 2011, we got this news that cat had killed on a roadside in Connecticut of all places and so we all sat up in our chairs and most of us just dismissed it as just perhaps this must be an animal, a pet that's been released, something that got out of the zoo or something. This couldn't be a real honest to God wild cougar, but lo and behold, six weeks later the DNA tests came back and determined this cat had come all the way from the black hills of South Dakota. Now he was a three-year-old young mountain lion. He had left probably when he was a teenager, about a year and a half old and set out on this incredible cross country journey that we believe may have taken his across at least six states and very likely he went across most of Canada's largest province of Ontario.

Stolzenburg’s book chronicles one cougar’s eastward trek. (Photo: courtesy of Sara Mercurio)

CURWOOD: Tell me about the circumstances in South Dakota, the Black Hills of South Dakota that might have prompted this lion to begin his journey.

STOLZENBURG: Well, what we have is a situation in the Black Hills of South Dakota that is rather unique. It's an island, it's a mountain island that is separated from the rest of the Rockies, and it is one of the most easternmost populations of mountain lions in the country, and what's happening there now is that the place is filled up with mountain lions, there's not room for very many more to go and as happens with all juvenile male lions when they come of age, when they're almost of breeding age, they head out. They head out and seek their own territory somewhere and most of them in the Black Hills head west back into prime cougar habitat. Well, a feel of the outliers headed in the wrong direction, as it turns out, they head east. We know, we're pretty sure why they're going there. They're looking for mates as I say in new territories, but there's a strange trickle of these eastern wandering cats that head out and that's where are our Connecticut cat started from.

CURWOOD: I imagine that any young male lion that heads east looking for a mate is probably just going to be out of luck. There are no females out there, are there?

STOLZENBURG: There's no females in the east, and they don't go as far as the males, and so this idea that they're on their way, it's just a stepping stone journey and they're going to be here in 20 years or so. Well, the problem with that is that the females don't make these huge jaunts as males do, even if they could survive it, they usually don't. To imagine a female doing what our Connecticut cat did in one big leap, you might as well put the money down on the Powerball. But what that leaves us is this other option, which is going to be a real controversial one, but which the some of the best minds in eastern cougars are thinking has to happen, we're going to have to start a colony. We're going to have to think of bringing the starter colony here and helping them along.

Journalist William Stolzenburg has written hundreds of science articles and two other books about living creatures, in addition to Heart of a Lion. (Photo: Kathy Stolzenburg)

CURWOOD: Now, one of the really cool things about your book, Will, is that you used modern DNA techniques to document this journey of this lion from South Dakota to Connecticut. So where is the first sighting of this lion where somebody gets some DNA?

STOLZENBURG: Yeah, well, it happened in the outskirts just west of Minneapolis in St. Paul in a little place called Champlin, and yet he showed up in the Mississippi River and was spotted by a police officer crossing the street. He jumped in the car and went chasing after this thing in the dark and actually got a video of this animal, so we know very well that this wasn't just him seeing something because we have a very clear video of this thing through a police dash cam of this animal walking through somebody's yard, just really amazing.

CURWOOD: And with the video, what about some DNA?

STOLZENBURG: Yeah, well they didn't get good DNA on that cat, but as it turns out, he was still headed eastward and a couple days later he did leaving some DNA. He wound up in this little nature reserve of an industrial section of town in Badness Heights, Minnesota, and he did leave his DNA in some feces.

CURWOOD: And why were those who were...had a vested interest in protecting this lion relieved when he left Minnesota and went to Wisconsin?

STOLZENBURG: The norm for animals doing what this animal attempted to do is to get shot. If they don't get shot, they usually get run over or they just seem to disappear. But none of them have been known to survive. The closest we have to something like that was a cat that in 2008 tried the same thing from the Black Hills, wound up in of all places downtown Chicago and there's dozens other. There's probably more than somewhere over 100, 120 cats that have died trying to make that trip across.

CURWOOD: From Wisconsin, the mountain lion, and I guess this mountain lion never really had a name...goes where?

STOLZENBURG: Yeah and he didn't have a name. They would name him as he went through town. The local papers would write him up as the Champlin cougar, or the Twin Cities cougar or the St. Croix cougar, but he made it to Wisconsin and then he headed north. What most people think is that he went through the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and crossed the international boundary in the St Mary’s river.

Male mountain lions sometimes travel great distances in search of a mate. (Photo: Bec., Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: And so, where does he go after that?

STOLZENBURG: So, the next place shows up is in Lake George, New York, in the Adirondacks. He was walking into somebody's backyard in the middle of night when their motion-sensing floodlight went on in and the lady washing her dishes at the kitchen sink was looking out the window when the light comes on and lo and behold, there's the mountain lion. It just so happened that her husband was a retired conservation officer who went out the next morning and sure enough they followed this mountain lion's tracks, and actually came to a bed where he’d laid and got a hair sample and that came back positive for this animal linking to the Black Hills of South Dakota.

CURWOOD: You know, you’d think the Adirondacks would actually be good territory for mountain lion. There's a lot of woods there.

STOLZENBURG: This animal kept going for some reason, and we think it's because he simply didn't find any females along the way, and if there had been, if there had been female lions there, very likely he would have stayed.

CURWOOD: So, what happens to him? He doesn't find love in the Adirondacks so he heads...

STOLZENBURG: He heads south. The next time we see him, he shows up 23 air miles from Manhattan's Central Park. He's in Southern Connecticut, in Greenwich of all places. He starts revealing himself like he has along the whole way. In the middle of the day, he's seen walking across somebody's patio in Greenwich, Connecticut.

CURWOOD: And so what happens to him?

STOLZENBURG: Yeah, that's where the story gets sad. A week later just past midnight just outside of the coastal town of Milford, he was killed. He was struck by an SUV. It's actually, there wasn't many cars on the road and when you consider all the different highways he crossed in his many many miles getting across United States. He'd overcome all the hurdles. All of a sudden he just made a mistake and stepped in front of the car on this night June 11.

A map charting the mountain lion’s journey from the Black Hills of South Dakota to Milford, Connecticut pinpoints some of the places he stopped along the way. (Photo: courtesy of Sara Mercurio)

CURWOOD: How sad.

STOLZENBURG: Oh, it was, yeah. I mean looking back it's truly a tearful thing when you consider the 18-month trip that this lion made across the country. But the bright side of it is again that this lion left an incredible legacy. He left this incredible line of evidence that proved many many things about mountain lions. He was really quite an ambassador for his species.

CURWOOD: Now, in your book, you document that not only did this cat, this mountain lion get all the way from South Dakota to Connecticut but he had to get through a gauntlet of people out with guns looking to kill animals like him.

STOLZENBURG: Yeah you know it's an unfortunate situation that in his home state they have a hunting season, they have a limited hunting season on the Black Hills itself, but in the rest the prairie for all those animals that are trying to escape, it's year-round. You can shoot an animal year-round. There's no limit.

CURWOOD: You said the other direction they go is west, and you write about California where people don't shoot mountain lions. Why is that?

STOLZENBURG: Well, 30 or 40 years ago, Californians voted against it. They decided years ago that they were not going to shoot their lions and the citizenry upheld that several times. California has the most people and most mountain lions of any state that has mountain lions, OK? They don't have the most conflicts, they don't have the most attacks, they don't have the most livestock lost to them, so the idea that most other states go by is that we really need to shoot these animals, keep them in their place, to protect people and their livestock. California is the antithesis of that.

CURWOOD: What does the research say about sport hunting's effect on preventing mountain lion attacks?

STOLZENBURG: Well, you know, there was a panel of blue chip lion experts who look at this situation 10 years ago, and they gathered all the evidence they could and they just could not find any science to back this idea that sport hunting in any way makes people safer, livestock safer.

CURWOOD: What do you think can be done if anything to shift long-held attitudes towards mountain lions?

STOLZENBURG: Well, I'm kind of hoping that that's happening right now and I'm hoping that maybe if the plight of the Connecticut lion gets a little more attention, thank you, that people will realize that there's a different beast out there than the one we've been told by the media oftentimes.

The Black Hills of South Dakota have a glut of mountain lions -- so some of the young males must leave the place of their birth. (Photo: Tambako the Jaguar, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, it's really interesting to talk about this because I spend some time in wild places when I can, and one of those places includes the Allagash where there's a guy who swore to me not once but at least twice he's seen these in northern Maine just across the border from Québec there.

STOLZENBURG: OK. Here's my answer to that. He could be right and he could be wrong, but here's why I think he could be right. Again we have thousands of these animals being held in captivity across the country, and this is often what happens when people realize they've got a cat they can't take care or they're tired of it and they don’t realize this is what it was going to take when their 10 pound little pussy cat turns into a 140 pound mountain lion. They let it go in places where they think, here's a good place for them to go. Unfortunately, they don't often survive.

Now, here's another thing that makes me think he could be wrong. There are stores like that everywhere you go and you can talk to some of the best naturalists across the eastern half of this country and they will swear up-and-down that they have seen these animals and 99 percent of time when biologists actually follow up on a lot of these so-called sightings, they come to the conclusion there's some other animal and then there's a whole other class of sighting out there which is under the hoax category and there's a whole bunch of people out there who would really like to fool us by posting stuff on the Internet.

CURWOOD: And, Will, before you go what you make of this notion that maybe a starter colony should come east?

STOLZENBURG: You know, I don't see why not. And I think this is just a matter of time. I think people are nervous of course because they know that we haven't lived with these animals for over a century now so it's really a strange thing to imagine them doing it. All you have to do though is go to California and you'll talk to people on the trails who say, yeah, I don't think much about it anymore. They're here, and that's fine. And so we can have mountain lions here, but it's going to be a big political fight to make it happen.

CURWOOD: William Stolzenburg is a wildlife writer and author of "Heart of a Lion: A Lone Cat's Walk Across America". Thanks so much, Will, for talking with us today.

STOLZENBURG: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Author William Stolzenburg’s official site

- Smithsonian: “Cougars on the Move”

- Mountain Lion Death Report

- Cougar Rewilding Foundation

[MUSIC: The Lion King - I Just Can't Wait to Be King - (Instrumental 1080p)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jaime Kaiser, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. We bid farewell today to Peter Boucher – thanks for your all help, Peter -- and we’re delighted to welcome a new intern, Jay Feinstein. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe, Noel Flatt, and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth