June 10, 2016

Air Date: June 10, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

UMass Becomes the First Major U.S. Public University to Divest

View the page for this story

The University of Massachusetts has decided to divest the five-campus system’s endowment from direct holdings in fossil fuels. President Marty Meehan tells host Steve Curwood how student activism, and a desire for moral leadership led the university to divest. (09:15)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra talks to host Steve Curwood about a proposed gasoline and diesel powered car ban in Norway, a new UN report about eco-crime, the fourth largest criminal enterprise in the world, and looks back to the 1692 earthquake in Port Royal. (03:55)

Mothers Raise the Alert on Gas Leaks

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Researchers have found over 20,000 natural gas leaks in Massachusetts. Now the group Mothers Out Front that campaigns for a livable climate is flagging these leaks, to alert their neighbors to the potentially explosive methane under their streets, and damaging the atmosphere. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer reports from the streets of Cambridge, Mass. (09:15)

Congo Pushes for Mega-Dam Project

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is trying to build the largest hydroelectric dam complex in the world, the Grand Inga. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb talks to Rudo Sanyanga of International Rivers about the Congolese government’s attempt to rush the project forward without a formal review of its environmental impact. (08:05)

Opening Glen Canyon

View the page for this story

Searing drought is causing people to rethink water infrastructure in the West, including some of the major dams along the Colorado River. ProPublica Reporter Abrahm Lustgarten talks to host Steve Curwood about a new plan to open the gates of the Glen Canyon dam to save massive amounts of water lost to leaks and evaporation. (16:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Marty Meehan, Rudo Sanyanga, Abrahm Lustgarten

REPORTERS: Helen Palmer, Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The University of Massachusetts has become the first major public university system to divest its endowment from fossil fuels.

MEEHAN: It reflects our commitment to take on the environmental challenges that confront our world. I also believe that higher education institutions have an obligation to show leadership on moral issues facing our society and because of the impact on future generations I think climate change is such an issue.

CURWOOD: Also, mothers organize to plant warning flags at the numerous natural gas leaks from old pipes under our streets, to protect the climate and their families.

ASHER ADAMS: I’m eight years old, and I’m really proud of my mom for helping everyone, not just us kids but everyone get rid of this thing that there’s so many gas leaks in pipes that could cause fateful damage to houses and property because it could catch on fire and make an explosion.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies. innovating to make the world a better more sustainable place to live.

UMass Becomes the First Major U.S. Public University to Divest

UMass Amherst students gathered outside of the Whitmore administration building on April 13, 2016, as 19 students who had participated in a sit-in were arrested and escorted out by university police. The University has now decided to fully divest from direct investments in fossil fuels. (Photo: Katherine Mayo / Daily Collegian)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. It’s our partner the University of Massachusetts that kicks off our program today, as it has become the first major public university system in America to pull direct investments in fossil fuels out of its $800 million endowment. UMass joins a growing movement that has seen public institutional funds worth more than $2.6 trillion fully or partially divest from climate damaging fuels, including the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Stanford University, the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation and two of the world’s biggest pension funds in California. University of Massachusetts President Marty Meehan says this landmark decision is key to the university’s broad program to address the existential threats of climate disruption, and he joins us now to explain. Welcome to Living on Earth, Marty.

MEEHAN: Thank you. Delighted to join you.

The distinctive W.E.B. DuBois Library on the UMass Amherst campus (Photo: Ryan Scott, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, how does it feel to be the first major public university to make this step?

MEEHAN: It feels good. I think this action is consistent with the principles that have guided our university since its land grant inception, and I think it reflects our commitment to take on the environmental challenges that confront us as a country and confront our world. I also believe that higher education institutions have an obligation to show leadership on moral issues facing our society and because of the impact on future generations, I think climate change is such an issue.

CURWOOD: What's the timeline here? How soon can we expect to see the University of Massachusetts actually sell off these shares?

MEEHAN: Well, when we talk to students they outlined kind of a five-year plan, but I think that we would be able to do that sooner than that. And in terms of how much money it affects, it depends on the given day that you check in with all our accounts. It could be anywhere from $5 million to $8 million. I think the most important number is the fact that there will be no future investments, so that while the amount of money that's invested in fossil fuels might go up and down prior to this decision, now we know it's only going one way which is down and there will be no future investments in any fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about your process. When did you begin having conversations about this and how has your thinking evolved?

MEEHAN: Well it's interesting because as early as 2014, the foundation's board of directors created a socially responsible investing advisory committee to evaluate social investment proposals put forth by members of the university community. So, for several years we've been looking at socially responsible investing. Last December, the foundation voted to divest itself from direct holdings in coal companies, and that the divestment has since been completed. At the same, the foundation pledged to continue providing and evaluating ways to manage the endowment in a way that promotes both environmentally sustainable investing, but also socially responsible investing. So it has evolved. I think the role that students have played have been important but I think it's always been something the university and the foundation board in particular has always been thinking and conscious of.

President Marty Meehan leads the University of Massachusetts system, overseeing UMass Amherst, UMass Boston, UMass Dartmouth, UMass Lowell and UMass Medical School in Worcester.(Photo: UMassDigital, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: How much of a role did student pressure play in this decision? I know there was an active divestment campaign particularly at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. I think more than 30 students were recently arrested there for occupying an office demanding divestment.

MEEHAN: It played a role. Any time students protest, I think it's fair to say that presidents and chancellors pay attention, and I know that Chancellor Subbaswamy at UMass Amherst, they got his attention. He talked to me about it and I had a conversation with students on the phone and then ended up driving out to Amherst to have a meeting with them. So I think it played a pretty important role. I mean, the fact is we weren't actively engaged in going to the foundation for direct fossil fuels investments and here we now—we are the first major public university in America to divest direct fossil holdings. So I think the students played a very important role.

CURWOOD: So, in the end, why do you think you decided to take this step?

MEEHAN: Because I think it sends the right message. I think universities should send the right message. I've talked to some folks who have said, “well is it really symbolic?” Well, I think symbolism is actually important. The university embraces the advantages of sustainability efforts every day on their campuses throughout research, our academic programs, our student engagement, our own energy policies. I hear some people say, "well, can you have more of an effect by, for example, we’ve reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 17 percent?" At Amherst, we've reduced emissions by 23 percent. Well the symbolism is important, too. So I think it's important universities such as the University of Massachusetts really address this from all angles, and I think symbolism in this case is important, and it got our students actively engaged and I think that's a good thing.

CURWOOD: Now, some money managers and other institutional leaders make the case against divestment, they argue that they have more power to influence the direction of fossil fuel companies if they still have a voice in the boardroom as shareholders. What do you say to that?

MEEHAN: Well, I say in this instance, a public university, a land grant university, it seems to me should be willing to do more than that. And I look at, for example, UMass Amherst ranked 21st in the 2015 addition of the Princeton Review's guide to 353 green colleges. If you promote yourself as a green university, I think it makes sense to take a further step and I would rather the University of Massachusetts be a leader rather than somebody that follows.

CURWOOD: To what extent do hope that other universities are going to follow suit here?

MEEHAN: Well, I think they will. I think this is a movement that has momentum. I think it's an issue that's not going to go away, and research universities in particular are very very important in terms of divesting but also in terms of increasing the use of renewable energy. I'll give an example, at UMass we've entered into 15 separate solar contracts with 10 different solar developers, so I think universities are already doing a lot of things but I think this divestment, I don't think it's going to go away and I think there will be more pressure from universities around the country to divest. And again divesting is only one small piece of the overall picture here. It's important for universities like us to continue to engage in academic programming and researchers that create next-generation thinking and technologies.

CURWOOD: So, what kind of response have you had from students, alums, perhaps even prospective students who might be attracted by UMass's divestment?

MEEHAN: Well, first of all, the students were very enthusiastic about it. I think they felt a sense of accomplishment. Prospective students are just as happy about it and I think that it may actually enable us to get more students who are environmentally friendly in thinking about global warming and thinking about issues of energy. In terms of alums I will say that there's some alums who want to make sure that we're maintaining policies with investment that will grow the endowment. One of the reasons why a lot of alums were investing in the University of Massachusetts is they believe it's critically important that the UMass grow its endowments so we can provide scholarships for students who want to attend the University of Massachusetts because as the cost of education goes up in many instances the amount of state support for public higher education goes down. Endowments play a very important role in leveling the field and making sure that a world class education is accessible to everyone, which means we needed the endowments and the scholarships that are provided to students to go up and certainly not down. So we have heard from our many alums that say, “make sure those investments are going to get the highest return possible.”

The fossil fuel divestment movement is not limited to the United States -- here, a group of divestment activists gathers in front of London’s Tower Bridge. (Photo: Alex, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Of course, over the short term, fossil fuel investments have underperformed in the market, so they must be happy.

MEEHAN: Yes they have. And I think that's a trend by the way that we'll continue. I think as we invest more in alternative sources of energy, I think that we're going to continue to see investments in fossil fuels going down.

CURWOOD: So where is the money that was being invested in fossil fuels going to go now?

MEEHAN: Well, I think that's up to the foundation board, but I think that we'll begin to see investments in clean energy. Now I'm not saying that specifically all of the money will go into to clean energy investments, but I do know the foundation has pledged to evaluate ways to manage the endowment in a way that promotes environmental sustainability, social responsible investing. So I'm hoping that they can find investments in mutual funds and other investments that look at clean energy, and I think those investments are going to turn out to be very good investments and I think that's one of areas the foundation will look to.

CURWOOD: Marty Meehan is President of University of Massachusetts. Thank you so much for taking your time with us today.

MEEHAN: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- University of Massachusetts on its divestment from fossil fuels

- Bloomberg: “University of Massachusetts to Divest From Fossil-Fuel Holdings”

- Boston Globe: “UMass climate-change protesters vow to keep up pressure”

Beyond the Headlines

A significant portion of greenhouse gases are emitted by gasoline or diesel powered cars. (Photo: Stefano Tranchini, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let’s see what’s up beyond the headlines now. Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, EHN.org and DailyClimate.org has been examining that world, and he joins us from Conyers, Georgia. How are you doing, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Doing alright, Steve. Let’s start with one of the most audacious climate change moves by an industrialized nation to date. Norway is reportedly set to ban the sale of all fossil fuel-powered cars by the year 2025, according to politicians from two of the country’s four major political parties.

CURWOOD: Whoa, not so long ago, that’s something no one would have expected.

DYKSTRA: Right. One of the four major parties had already proposed a ban on gasoline and diesel cars by 2030, but this would step on their gas-free pedal and speed things up by about five years. And the fourth Norwegian party says they’re considering the 2025 deadline, that’s less than 10 years from now! Bear in mind that this is a country where the rival political parties work together on things.

CURWOOD: What a concept! And on this particular question I mean really taking the vroom out of driving. How can it be done?

DYKSTRA: Consider what Norway’s already done. In the past few years, they divested their $900 billion national pension fund from fossil fuels, they’ve committed to tripling their wind energy output, and already 24% of all the cars in Norway are electric.

CURWOOD: If they divested their national pension fund from fossil fuels, they had to divest from their own product because they’re still a major oil producer, right?

DYKSTRA: Right. They produce about two million barrels a day, with no similar plan to end oil drilling.

CURWOOD: Hmm. Hey what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: A report from the UN Environment Programme and Interpol says that eco-crime is growing quickly and could be worth as much as a quarter-trillion dollars a year.

Eco crime, such as toxic waste dumping, is the fourth largest criminal enterprise in the world. (Photo: Alexander Synaptic, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: That’s pretty big business. How do they define eco-crime?

DYKSTRA: Well, Interpol says eco-crime is the fourth biggest criminal enterprise in the world, and it includes wildlife poaching and smuggling, illegal fishing, logging and mining, toxic waste dumping, and more. Eco-crime has been growing at about five to seven percent a year for most of the past decade, but the UN and Interpol say that rate has doubled in the past few years.

CURWOOD: So what are they doing, just wringing their hands, or have they got some plan for action here?

DYKSTRA: Well they’ve got a few solutions, but they’re not pretending that this is a problem that’ll be brought under control any time soon. The amount spent battling eco-crime by international agencies is somewhere between $20 and $30 million a year, so bulking up there is one obviously helpful thing they can do.

CURWOOD: Yeah, because you said this business is worth, what, up to a quarter trillion dollars? I mean that’s a lot of dough.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, those two numbers don’t really match up, do they? The perpetrators range from the desperately poor and hungry to lone wolf entrepreneurs to organized crime, rebel armies and corrupt governments, all of whom don’t seem to mind if the phrase “lone wolf” becomes a reality someday.

CURWOOD: Gee Peter. Thanks for cheering us up with that news. What do you have from the history vault this week?

DYKSTRA: This past week back in the year 1692, the “Wickedest City on Earth” experienced a little problem. Port Royal, on a spit of land at the mouth on Kingston Harbor in Jamaica, was a haven for pirates and debauchery and prostitution. One of its most famous privateers and rumrunners was Captain Henry Morgan.

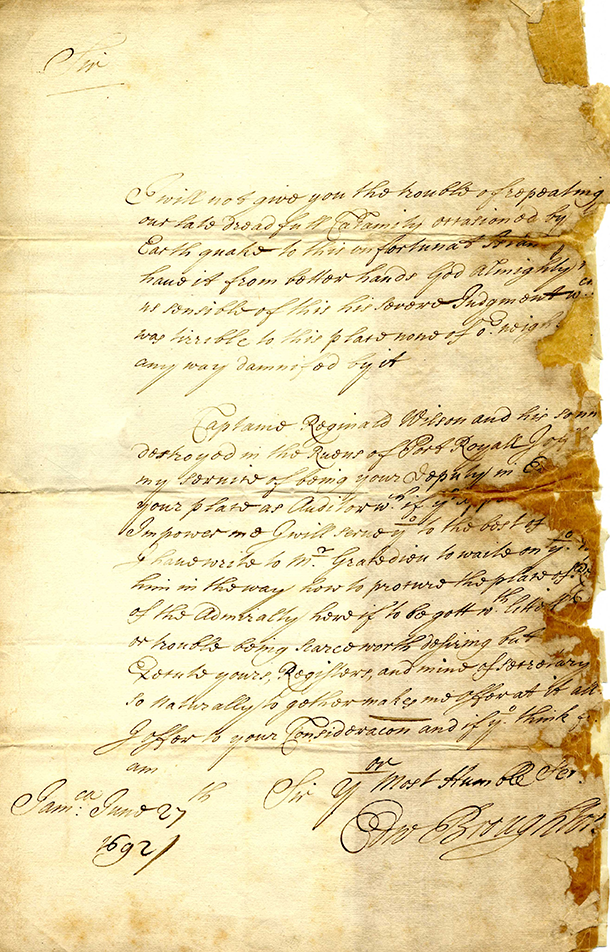

William Blathwayt, Secretary of War in England, received this letter after the 1692 Port Royal Earthquake. (Photo: Williams Ethnological Collection, John J. Burns Library, Boston College Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Oh, Captain Morgan, the same name that is immortalized on rum bottles these days, huh.

DYKSTRA: Right, and just before noon on June 7, 1692, a massive earthquake rocked the Caribbean, and a 40 foot wall of water buried Port Royal. Sixteen hundred people died immediately, and another three thousand eventually perished from injury and disease. Parts of the city slid into the sea, and portions of it are still underwater – an archaeologists’ dream and now a UN World Heritage site. It was left to Jamaica’s colonial government to declare what just about everyone was thinking. They said, “We are become by this an instance of God Almighty’s severe judgment.”

CURWOOD: Yeah, just like the Bible says, “God brought down his judgment on Sodom and Gomorrah.”

DYKSTRS: Right.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org, and dailyclimate.org. Thanks, Peter. We’ll talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: Thank you, Steve. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- The Independent: “Norway to 'completely ban petrol powered cars by 2025’”

- EIA statistics on Norway’s oil output

- The Guardian: “Value of eco crimes soars by 26% with devastating impacts on natural world”

- History of Port Royal Quake

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4wLLJTHu2k

Mike Forde/Dave Merrick, “Calypso Farewell,” Lord Burgess (Irvine Burgie), not commercially available.]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...missing in action...an environmental impact assessment of plans to build the world’s largest set of hydropower dams. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from Wunder Capital, an online investment platform that allows individuals to invest in solar projects across the U.S. More information and account creation at Wunder Capital.com That's Wunder with a 'U'. Wunder Capital, Do well and do good.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Munnelly, “Ar Bhoitrin Na Smaointe,” By Heck, arr. D.Munnelly/R.Molloy, Mad River Records]

Mothers Raise the Alert on Gas Leaks

The Mothers Out Front and their kids included Audrey Day-Williams, Beth Adams, Asher Adams, Emma Day-Williams, Greta Koechner, Thomas Koechner, and Susan Koechner (Berwin Adams is hiding behind his older brother Asher). (Photo: Ellen van Bever)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. Natural gas is touted as the bridge fuel to wean the US off dirtier fossil fuels. It’s plentiful, due to fracking and seen as less carbon intensive, until you factor in that it’s mostly methane, a potent greenhouse gas, and that much more of it leaks into the atmosphere at every stage of production and delivery than its boosters acknowledge. When it comes to the last stage, as it’s delivered to our homes, the quantity that leaks is staggering and shocking, partly because much of the gas pipeline system is old and corroded. Now some citizen activists in Cambridge, Massachusetts have decided to alert their neighbors to the danger that seeps up through their pavements, and Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer has been out with them.

A computer image depicts gas leaks in Somerville, MA (Photo: courtesy of Home Energy Efficiency Team)

[STREET SOUNDS]

PALMER: It’s a chilly drizzly afternoon as three mothers with 5 children, and me in tow, head out onto the streets. They’ve got fistfuls of yellow flags, posters and fliers to mark some of the 200 odd gas leaks in Cambridge Massachusetts.

The Mothers Out Front and their kids tag gas leaks in Cambridge, Massachusetts Thursday, May 5th, 2016. Video courtesy of John MacGibbon and Mothers Out Front.

ADAMS: So I’m Beth Adams, and I live in Cambridge. I’m mom to Asher who’s 8 and Berwin who’s 6…

Alexandra Dellman, a Cambridge homeowner and mother, with her kids (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: Beth’s part of the group Mothers Out Front, Mobilizing for a Livable Climate.

ADAMS: We’re a group of moms and grandmothers and other caregivers who’re concerned about climate change and all children and their future. Our ultimate goal really is to transition as quickly as possible from fossil fuels to a clean renewable energy future.

PALMER: To push towards that goal, Beth Adams and the other moms – Susan Koechner, and Audrey Day-Williams and their children are flagging the 8 or so leaks in this small part of North Cambridge…

ADAMS: So we have one right here and we have 2 across the street very close together.

Kid: Can I put a flag?

PALMER: Leaks aren’t a new problem for this antique gas pipeline system, indeed for years a Boston University team has been driving round the streets with a sensitive detector to pinpoint exactly where gas is escaping. Their map of Boston’s leaks spurred citizens in other communities to take action. Audrey Schulman is president of the Cambridge non-profit Home Energy Efficiency Team, or HEET. HEET works with the utility-funded program Mass Save that helps residents cut their personal carbon footprint and costs. Audrey read about the BU team and its gas detecting device in the Boston Globe.

8-year-old Asher Adams ties a notice to a post, while Emma Day-Williams, Greta, Thomas and Susan Koechner watch. (Photo: Ellen van Bever)

SCHULMAN: And one line in the article said that the amount of gas lost totally erased all of the efficiency programs through Mass Save in terms of their damage, and from that one line, I thought I must do something, this is an issue I must take on.

PALMER: So she borrowed the gas leak analyzer from Professor Nathan Phillips and drove it round Cambridge and Somerville mapping everywhere it detected methane. But she realized she could take this exercise further, thanks to new legislation.

Audrey Schulman of the Home Energy Efficiency Team (Photo: Home Energy Efficiency Team)

SCHULMAN: In 2014, for the first time ever, the utilities had to report on the location and age of every gas leak in their territory so I found those reports and I thought “I can map this” so I mapped over 20,000 gas leaks across Massachusetts in over 200 municipalities.

PALMER: And then she checked the leaks she’d mapped with the methane detector in Cambridge and Somerville against the lists the utilities had provided – though there remains some uncertainty about how comprehensive those lists actually are.

SCHULMAN: The interesting thing, when looking at what the utility reported as opposed to what we had found was in Cambridge we found 30% more gas leaks than the utility was reporting and in Somerville we found almost double the number the utility was reporting.

PALMER: And that’s how come now the Mothers Out Front are out on the streets of Cambridge with their kids to alert citizens to leaks outside their doors. Beth Adams consults the gas leaks map …

Doorknob signs alert residents to nearby leaks (Photo: Helen Palmer)

ADAMS: So we have a map of the leaks in this area. So we’re going to put down a flag, and the flag reads: “the nose knows: methane gas leak nearby.”

ADAMS: Let’s put it here.

KIDS Where can I put the flag?

ADAMS: Put it right here…

PALMER: They stick the bright yellow plastic flags into the ground beside a street tree, and tie an information sheet on a nearby pole.

ADAMS: So we’re attaching our sign here and we’re educating our neighbors, our colleagues, our elected officials and it says, “we have over 20,000 gas leaks statewide. Eversource is passing the cost to us. Leaks speed up climate change, kills trees and waste energy.” And so there’s a gas leaks right here; in fact there are 3 just within about 30 feet of each other. So we have here: “methane is leaking from underground gas pipelines near here. Find your local leak and take action for our children’s future.” You need another tie to fit it round the tree? Thank you for helping.

PALMER: The gas that’s lost through leaks is not insignificant. Audrey Shulman says a joint 2015 study from Boston and Harvard Universities calculated both what was lost, and what it cost.

A flag warns Cambridge residents of the methane leaking nearby (Photo: Ellen van Bever)

SCHULMAN: You know, from the results that it found in the Greater Boston area it calculated that about 2.7% of all the natural gas that we’re trying to get to our homes and businesses to use is being leaked out, being wasted by these aging pipes buried under the ground. So that’s about $120 million per year in Massachusetts alone.

PALMER: And, of course, it’s customers that pay for that lost gas; it’s reflected in the unit price that utilities charge, though there is a bill currently in the state legislature to prohibit the companies from pushing the cost of this wastage onto we the people.

ADAMS: So we’re going to the end of Linnaean here – sorry Avon Hill..

PALMER: And as the Mothers plant their flags, the kids run ahead to hang fliers on the door handles of the houses closest to the leaks– and what they’re doing grabs the attention of Michael Connolly, a tall elegant white haired man walking his two golden retrievers. He takes a flier. I ask why he’s interested.

A Mothers Out Front poster warns of gas leaks (Photo: courtesy of Mothers Out Front)

CONNOLLY: Well, 2 reasons really. There’s a safety issue, but I’m also aware that gas leaks are – I would say 100 times more prevalent than I would have guessed 5 years ago. That’s an economic issue and it’s a climate issue, and it’s crazy that we pay for infrastructure and then let it degrade and waste our resources – so that’s why.

PALMER: And as we walk on, Alexandra Dellman comes out of her house to take her children to the park with their scooters – and sees the flier the kids have just hung on her doorknob.

DELLMAN: I think it’s important stuff to know and I’m quite surprised that the residents around here don’t know about it and I’m pleased it was brought to our attention. I mean it’s definitely a worry, it’s a worry for the environment, it’s a worry on a safety and heath level and I think definitely we should put some pressure on the companies to get these leaks fixed.

PALMER: One effect of all the publicity and attention now being paid to all these gas leaks is that – yes – the leaks are getting fixed at a much faster rate. But Audrey Schulman is not impressed.

Alexandra Dellman, a Cambridge homeowner and mother, with her kids (Photo: Helen Palmer)

SCHULMAN: Becasuse of a 2014 law, they are increasing the speed of infrastructure repair, of replacing the pipes these aging pipes under the street, by 400%. So instead of replacing all the old leaky pipes in 80 years, they’re now hoping to get it done in 20 – 25 years. Which seems like still a really long time to me, because methane is such an incredibly damaging climate gas.

Michael Connolly is a Cambridge homeowner (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: The state’s two main utilities, Eversource Energy and National Grid, say they plan to spend billions over the next few years to fix the worst leaks. Now a study just released by a graduate student at Boston University found that 50% of the gas lost comes from just 7% of the leaks, meaning that fixing just those leaks would go a long way towards cutting the wastage, and the dangers that methane poses to health and the climate. In the meantime, the Mothers out Front and their children will continue to pound the pavements and flag the leaks to let people know what’s going on under their streets. It’s a campaign that some of the kids take seriously too – Beth Adams’ son Asher.

ASHER: I’m eight years old, and I’m really proud of my mom for helping everyone, not just us kids but everyone get rid of this thing, that there’s so many gas leaks in pipes that could cause fateful damage to houses and property because it could catch on fire and make an explosion. PALMER: So is one of the reasons you’re out here because you care about your future? ASHER: I really do care about my future and everyone else’s too.

PALMER: And faced with such moral conviction and sentiment from the mouths of 8 year olds, the utilities would find it hard to argue for any delay in fixing the persistent, wasteful, and destructive leaks in our decaying gas pipeline system. For Living on Earth, I’m Helen Palmer in North Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- City Maps of Gas Leaks in Massachusetts

- Mothers Out Front

- The “Natural Gas Leaks Bill” compelled utilities to declare leaks and was signed into law in 2014

- Massachusetts bill H.2870: a petition to protect customers from paying for leaked gas

- Massachusetts bill H.2871: a petition regarding gas leak repairs during road projects

- Listen to an earlier LOE story about gas leaks in Boston

- Lost and Unaccounted Natural Gas: research from Boston University

- Boston Globe: “Missing Gas Leaks Raising Questions”

- Bill McKibben for The Nation: “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Chemistry”

[MUSIC: (Sesame Workshop) The Kids, “Sing,” Sesame Street Playground, Joe Raposo (Jonica Music), Putumayo Kids.]

Congo Pushes for Mega-Dam Project

Inga 1 power station, the first of what the Democratic Republic of the Congo is planning to have as part of a massive seven-dam hydropower system, (Photo: International Rivers)

CURWOOD: Much of Africa is both poor and underdeveloped, lacking such basics as reliable electric power. But the Inga 3 Dam on the Congo River, part of Grand Inga, the world's largest hydropower scheme, has long been touted as a model for the Africa energy sector by the World Bank and the World Energy Council. Inga three would pump out 4800 megawatts of power, and the whole Inga system would generate 44,000 megawatts — bigger than China’s Three Gorges dam system. But things have not gone smoothly, and after long delays, the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo is pushing for a rapid start of construction, likely with Chinese dam builders. Yet there has been no Social and Environmental Impact Assessment of the project, and developing Inga 3 without it would violate national law, World Bank policies, and Chinese guidelines for overseas contractors. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb went to get more details from Rudo Sanyanga, a dam opponent and the Africa Program Director of International Rivers in Pretoria, South Africa.

Congolese boatmen (Photo: International Rivers)

BASCOMB: Rudo Sanyanga, please tell me about the proposed Inga 3 dam and the Congo Dam complex. How should a project like this normally get started?

SANYANGA: Usually there is the Project Impact Assessment studies, which look at all possible impacts. It also ends up the impact studies with a decision on whether the project should go ahead or not based on the level of impacts. And if there is need for people to be displaced than there is also a resettlement action guide that is attached to that. The whole process especially for such a large project should take not less than a year, and will involve a lot of experts in various areas—geologists, sociologists, environmentalists, hydrologists—to make sure the project is done, or implemented with the highest world standards.

BASCOMB: And from what I understand the Congolese government doesn’t want to do an environmental review for this project.

Panorama of the Inga dam site (Photo: International Rivers)

SANYANGA: In March 2014, the World Bank approved 74 million US dollars, and part of that was to carry out technical studies, which included the environmental impact studies, the resettlement action guides, and compensation studies. Unfortunately because of some misunderstanding between the World Bank and the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the money has not been released. Nothing has started at all. The government of DRC is becoming impatient and they want to go ahead with the construction.

BASCOMB: Well if this dam proceeds as planned right now, how do you think the environment and local communities will be affected? I mean who lives along this river?

SANYANGA: There are a number of communities that live very close to the Bundi Valley and those will have to be moved. It’s estimated that 10 to 25 thousand and more as the dam stages increase. So those people will have to be moved and definitely be impacted. The level of impact will depend on how they are settled. Sometime some of the displacements and resettlements have moved people to a totally different kind of environment where they have no skills to survive. And sometimes much drier areas where they used to rely on flooding and river water and they have no access to that. And we’ve found a lot of communities that have been displaced by dams becoming impoverished because of that.

Inga 2 dam (Photo: International Rivers)

BASCOMB: What about wildlife? The DRC is known for biodiversity of its rainforest.

SANYANGA: Yeah but on the eastern DRC in this area there is not much big, large animals. There is aquatic life, and some endemic species are found around Inga falls. We don’t know what the diversion of water will cause to those animals. In addition there is also the Congo Plume phenomenon, which is the largest carbon sink in the world, on the Atlantic Coast where the Congo River pours its sediment. The sediments bring in a lot of nutrients and there are certain microorganisms that feed on those nutrients and use carbon dioxide from the air in their metabolism. So as they do so they absorb a lot of carbon dioxide and release oxygen, so it’s regarded as a carbon sink. And it’s going on a phenomenal level. We don’t know what the impacts will be because sediments will be trapped behind the dam walls and not all sediments will be able to reach the ocean. So those are some of the concerns and the issues we have raised, and which should, if an environmental impact assessment study was going to go on, should be answered by those studies.

People who would be relocated for the construction of Inga 3 (Photo: International Rivers)

BASCOMB: The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a really poor country. They’ve seen a lot of war and instability. Supporters of this dam say they need it to bring energy to an impoverished country.

SANYANGA: Yes the DRC needs energy, but the model they are using doesn’t show that the energy will benefit DRC. Inga 3, generating 4800 megawatts, 2500 of that power will go to South Africa. 1300 is going to Katanga the mining town on the Southwestern side of DRC. And the remaining 1000 megawatts is targeted for Kinshasa. During transmission it’s projected that a minimum of 20% will be lost. So what it means if the agreement requires that the delivery is say 2500 megawatts to South Africa, and South Africa has to receive 2500, it means DRC from the Inga where they push the power on the transmission line, they have to push far more than the 2500 to make up for that loss. Which means the excess energy that is promised for people in Kinshasa will not be necessarily available at all times. Secondly, because of the infrastructure, which is outdated, it might not be able to transmit that remaining energy to Kinshasa.

Rudo Sanyanga (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: And so the people living in the villages, not connected to the grid, are they going to benefit at all from this dam?

SANYANGA: Not at all. Even in the best of scenarios it is unlikely they would benefit because there is no grid connection to the majority of the country. It would be costly to connect all those people to grid connection in isolated villages. So the best way of supplying energy to these isolated villages in Africa is probably decentralized energy from perhaps solar, wind, and mini and micro hydro. So we are not necessarily opposed to all dams. It’s just there’s no proper plan on the table to show how this project will be implemented, how it will benefit the people, so that’s the concerns that we have.

CURWOOD: Rudo Sanyanga, the Africa Program director of International Rivers, in conversation with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb. We asked the Embassy of the Democratic Republic of Congo for comment multiple times; they did not reply by our deadline.

Related links:

- International Rivers

- Read more about Grand Inga dam

- Rudo Sanyanga

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XxRPuK_kbOg

Papa Wemba, “Yolele,” Emotion, Real World Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...huge dams have brought power and water to millions – but some may have outlived their usefulness. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Christopher O’Riley/Matt Haimovitz, “Vertigo Suite-Carlotta’s Portrait,” Shuffle. Play. Listen., Bernard Herrmann/arr.Christopher O’Riley, Oxingale Records]

Opening Glen Canyon

Lake Powell behind the Glen Canyon Dam (Photo: Alan English, Fickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Searing drought has sparked soul-searching about water management in the arid West, and some now question the viability of dams and other infrastructure to supply water to cities and farms throughout the region. Abrahm Lustgarten is a reporter for ProPublica, and he has a new story about one of the largest dams in the US, Glen Canyon, and a recent push to open up its gates. It’s a remarkable development, given how important the Colorado River dams—Glen Canyon with its reservoir Lake Powell and Hoover with its reservoir Lake Meade—have been for the development of the West. Abrahm Lustgarten joins us now to talk about the story, welcome back to Living on Earth, Abrahm.

LUSTGARTEN: Hi there. Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: First of all, for someone who has never seen it, what's the Glen Canyon Dam like?

LUSTGARTEN: The Glen Canyon Dam is a huge, impressive really awe-inspiring structure. Like the Hoover, which looks very similar, it's about 700 feet tall, it fills a very tight dramatic canyon in the Colorado River and you can come to a viewpoint or drive across the road right in front of it. So you have this, it’s almost like you're hovering in a helicopter. You get to look down on the lake and look down the dam and it's just this massive plug of concrete.

CURWOOD: So take us back to the time when the Glen Canyon Dam was first built. What was the attitude about dams back then?

LUSTGARTEN: So, Glen Canyon Dam was built in the 1950s, and the US was in the middle of a real dam building spree in the western United States. Starting in that early 1900s, 1920s, they started building dams up and down the Colorado River in particular to harness that resource and find a way to distribute it far outside of the river's natural course—hundreds of miles into Arizona, hundreds of miles into California and also to control some of the flood torrents that could come downstream in big water years. The Glen Canyon dam was built kind of the tail end of that spree after number of other dams had been built and it had more of a political aim. The upper basin states in the Colorado River - Wyoming, Colorado New Mexico, and Utah - they were worried that the lower basin states - California and Arizona, Nevada - were taking too much water, were growing too fast and they basically wanted a gate, and Glen Canyon Dam was built as their way to hold back water so they wouldn't have to give more than they were legally required to those states in the south.

Journalist Abrahm Lustgarten (Photo: Lars Klove)

CURWOOD: Now, how essential have the Glen Canyon dam and the other megadams on the Colorado been over the years for the water supply of the west and southwest?

LUSTGARTEN: I don't think you would see a western United States that you recognize if it were not for, at least the Hoover Dam, if not both of those two dams being constructed. The Hoover Dam in particular stemmed an enormous flow of huge floods that would come down through Arizona and the southern tip of California on a regular basis, very difficult for those other agricultural areas to manage, very difficult to capture and use that water. So the Hoover Dam served a really clear purpose in terms of both generation of power and then creating a water reserve. Lake Powell essentially created another enormous water reserve, created an enormous generator of power when that reservoir was full. It's less of a flood control purpose, but what it did is gave the seven states a way to kind of regulate their agreements between one another as the big cities in the west grew. So as Los Angeles and Phoenix and Tempe and Denver all started competing more and more for that water, that gateway function that I described became more important and Glen Canyon really the regulator for this giant system.

CURWOOD: And just to remind people of the geography here, the lake behind the Glen Canyon dam is called Lake Powell. The impoundment behind the Hoover Dam is called Lake Mead. Now, David Brower was the first executive director of the Sierra Club and he's famously quoted as saying, agreeing to the Glen Canyon dam construction was his biggest regret. Why did he agree to it and why did he come to quickly regret his decision?

LUSTGARTEN: On the list of dams that the US Bureau of Reclamation was building was a proposed site at a place called Dinosaur National Monument and that's in northwestern Colorado and it was an established park. It's really phenomenal place, full of dinosaur bones and fossils and a lot of really rich history and that was a place that everyone knew, and David Brower knew and they fought hard to protect it. And through that really lengthy environmental fight they reached an agreement that they would not build a dam at Dinosaur National Monument, but the environmentalists wouldn't oppose a dam at another site, which was at Glen Canyon. And David Brower lived in Berkeley, California, and wasn't familiar with Glen Canyon, and he didn't have a sense of its majesty, and it was only later after he did come to make that tacit political agreement that he did visit Glen Canyon and he traveled it with the photographer Elliot Porter and they published this incredible book called "The Place No One Knew" and then before the dam was built but after everything was in process he began to oppose that dam site.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, of course, Glen Canyon is famously located just upstream from the Grand Canyon. It's amazing territory.

LUSTGARTEN: Just 20 miles north of the Grand Canyon or upriver from the Grand Canyon, really the moment you're below the dam structure itself at Glen Canyon you're entering what you would recognize as the Grand Canyon.

CURWOOD: We have a recording of David Brower talking about his visit to Glen Canyon and his inability to block the dam. This is from the 1997 documentary film series "Water and the Transformation of Nature".

BROWER: I've seen the canyon, and I've seen the side canyons, my family had seen them and I knew what a beautiful place it was. I testified in the lack of comprehensive thinking that had gone on in the entire project and came up very strong arguments for stopping the entire project. And I wanted at least at the last moment to appeal to Stewart Udall and I wanted to get in to talk to him because that was the last day they're going to close the gates and start filling Glen Canyon. And I got to his office but never got to see him because he had this other agenda. I did have this last desperate hope that we could stay the closing of the dam, the closing of the river valves and stop any further filling until we thought a little bit harder about the alternatives. And that January of '63, I failed.

CURWOOD: Stewart Udall was a Democratic congressman from Arizona and later Secretary of the Interior. Despite protests, Glen Canyon was built, adding another dam to the Colorado River, which already had the largest one in North America, the Hoover Dam. But in recent years activists have started to point out that many dams have outlived their benefits. Dams have now come down on many rivers including the Elwha in Oregon and soon they'll be decommissioned on the Klamath, which runs between Oregon and Northern California. And given the changing weather patterns people are now even talking about opening up the gates of the Glen Canyon dam. Abrahm Lustgarten says each of these situations is unique.

Aerial view of Glen Canyon Dam and Wahweap Basin of Lake Powell. (Photo: Bureau of Reclamation)

LUSTGARTEN: The circumstances of dams are very specific to their local geography and each faces different issues. In the northwest, the problem is the interruption of salmon migration, a really substantial ecological impacts. The Colorado River, it's a really different situation. There are endangered fish species in the Grand Canyon, but it's not as much as a question of the lost landscape of Glen Canyon, the damage for Grand Canyon of having unnatural flows through that river, and most significant to me the great inefficiency in terms of the water that's lost off the surface of these dams. The big dams on the Colorado River were built to save water, and what happens is because the water is spread over such a large area in such a hot and dry environment, an enormous amount evaporates off the surface and that didn't matter so much in the past but as waters become more and more scarce that amount of water that's lost is significant enough to make a real difference.

CURWOOD: Just how much is lost that way?

LUSTGARTEN: So, Lake Powell loses about 350,000 acre feet of water each year to evaporation and that's enough when you combine it with the amount of water that also seeps out the bottom of Lake Powell, another form of loss, it’s enough to supply about nine million people with water each year, about the size of the city of Los Angeles. Lake Mead also loses a similar amount and so does each of the reservoirs up and down the Colorado River system. When you add all that up together in a system that is over-allocated every single year, you basically see an inefficiency that could add roughly 30 percent more to the river's flow.

CURWOOD: So, how could that efficiency be addressed? If you take down the dams, it would seem you lose control of the water and yet if you have a dam with a lake behind it, it's going to evaporate. Seems like it's kind of a Hobson’s choice there.

LUSTGARTEN: Well, you're right except for the fact that both Lake Powell and Lake Mead are in a dilemma that they haven't been in since they've been created, and that is they're both essentially drying up. So for the last 16 years we've had unusually low flows in the Colorado River yet those states of continue to take their full allotment out of the river every year and essentially been drawing on those two huge reservoirs as a savings account and those savings accounts are almost drained. Lake Mead is now about 37 percent full. Lake Powell is just a little bit less than half full. Both reservoirs still lose an enormous amount to evaporation but they're not functioning at their full capacity, both in terms of the power to generate or the amount of water that they hold. So the ratio of inefficiency to benefit has just changed substantially over the last decade or so of drought.

CURWOOD: So Abrahm, what's the case for taking down the Glen Canyon Dam?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, the proposal to get rid of Glen Canyon Dam comes from the Glen Canyon Institute. It's an environmental organization. They've had a bias from the earliest days with David Brower towards restoring Glen Canyon but now they have a real pragmatic force behind their argument, and what they're essentially proposing to do is combine the two reservoirs. If they're both half-full their proposal is to empty Lake Mead, combine it with Lake Powell, not lose that water but send it 300 miles downstream and recollect it so you have one full large reservoir. You significantly decrease the amount of water lost to evaporation because you've decreased the total surface area that's exposed to the elements. You increase the power generating capacity of Hoover Dam which helps make up for what you lose in terms of power generation at Glen Canyon dam and a nice little a side effect bonus is the opportunity to actually restore the landscape of Glen Canyon.

The Colorado River (Photo: Denny Armstrong, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now why would Lake Mead be more watertight than Lake Powell?

LUSTGARTEN: It's just a factor of the local geology. The valley that Lake Mead filled is not one that geologists just have found to absorb a very large amount of water and to siphon that water away from that geologic basin that it sits in. Lake Powell on the other hand sits in a geologic basin that's full of very porous sandstone, a different kind of sandstone from Lake Mead and lots of cracks and fissures. And for a long time it was believed and the Bureau of Reclamation still believes that water seeped into the ground but eventually returned to the Colorado River. I was looking at some research, fairly new research from the last couple of years that's examining where those hydrologic gradients go and determined that the water isn't returning to Lake Powell, that about 380,000 acre feet again, an enormous amount of water is permanently lost each year out of the bottom of Lake Powell.

CURWOOD: So one of the reasons of course that the Glen Canyon Dam went up, you wrote about is that it allowed the states further upstream, communities further upstream, to have more control over water. How are they going to feel about the water going 300 miles away and out of their direct control?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, that's the big fight right there, I mean, most of the resistance to this idea, or the scoffing even that this idea is coming from those northern states and what they see is a political threat more than anything. They say that the existence of Glen Canyon Dam is the mechanism that allows them to comply with what's called the Colorado River compact and that's this legal agreement to send seven and a half million acre feet of water down to the south every single year and they say that if they don't have that dam there that they won't be able to meet that obligation. So in the most reactionary of terms they described the suggestion of removing Glen Canyon Dam as something that would require a renegotiation of that compact agreement, probably congressional approval and really involved bureaucratic process. What it basically means is that they don't want to lose that hands-on control over their water. Legal experts I spoke with, however, suggest that both the upper and lower basins could share the water out of Lake Mead. It doesn't have to continue in the traditional role of serving only the southern basins and that the accounting for that water could still happen at a place called Lee's Ferry where it happens now which is just below the site of the Glen Canyon Dam.

Water infrastructure along the Colorado enabled the development of large Western cities including Los Angeles (Photo: David Galvan, Flickr CC BY NC ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: My guest is ProPublica’s Abrahm Lustgarten, who’s been writing about how the changing climate is throwing doubt on the value of megadams. So how realistic is it to think of opening the gates of the Glen Canyon dam, in the face of political pressure from states upstream?

LUSTGARTEN: So this is the question that I posed to the deputy secretary of interior Mike Connor and he's ultimately the person charge of water in the west and the short-term answer is that it's not realistic. This is probably not something that's about to happen, but what we see through the removal of dams across the western United States, whether it's on the Klamath or elsewhere and there were five, six dams removed just in the last year is that the idea of a dam not suiting its original purpose is a topic that can now be broached. So when water managers look at the Colorado River basin and how to manage the extreme deficits there, really for the first time ever at least this is part of the conversation and that's, that's what I'm seeing change. Whether things get dire enough, whether as I put in the article those western states decide they need the water badly enough to actually take the dam down, I think that remains to be seen, I think it'll take some time. But this is a conversation that was laughable a couple years ago and now at least is taking place in a very serious way.

CURWOOD: With all this talk to decommission the Glen Canyon Dam, that is to let it drain, what would happen if nothing is done?

LUSTGARTEN: If nothing is done at all, then the future really depends on how much water flows into the river and how much water the states continue to take out of it. The bottom line is the Colorado River will never be sustainable until the amount of water the states take from it matches what is naturally available. If that doesn’t change, if the states continue to draw every single year more water than flows out of it, than these reservoirs are going to drain. It could take another ten years it could take two years but they’re going to drain to the bottom. Researchers at Scripps School of Oceanography at UC San Diego predict that there is a 50% chance that Lake Meade will run dry by 2021. So this is in a way inevitable. So we’ll see this proposal to save Glen Canyon happen one way or another, whether it’s the result of a political decision and the renegotiation of the river compact, or just the result of a diminishing supply of water and it eventually draining down to a small puddle in the bottom. The alternative is what you see California and Arizona and Nevada working towards now. Not quite a renegotiation of the compact but an agreement to take less water. They’ve got a long ways to go. They’ve got to take far less water than even this agreement would allow them to take. But if you can reach a point where states are happy to use only the amount that’s available, or perhaps their share is proportional to the amount of water that is available in any given year, then you could see a system where the flows could once again be regulated and governed and these reservoirs might serve a purpose because the draw on them is predictable.

The Colorado River and the Glen Canyon Dam (Photo: Jim Trodel, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, Abrahm, you're a reporter, you're not a hydrologist, you're not a fortune teller, but tell me, with the trend of climate disruption proceeding, and continuing to dry out the southwest, how realistic in your view, are these adjustments that people want to make in terms of really responding to the water shortage crisis that seems to be inevitable?

LUSTGARTEN: I think from my observations that they're happening painfully slowly, but I also think they are inevitable. This isn't hyperbole, this is actually happening, and you're seeing it right now in the southern basin where California, Arizona and Nevada are voluntarily coming to the table and reaching an agreement to voluntarily give up part of their share of the Colorado River, just to try to preserve Lake Mead. So, for California, especially, this is extraordinary. California holds a very senior legal position. It guaranteed to get its water, no matter what, out of the Colorado River Basin. The fact that its at the table volunteering to give some of it up is historically unprecedented and I think shows how deeply concerned these states are that the Colorado will actually dry up and if it's not managed carefully, that will happen. It's almost inevitable.

CURWOOD: Abrahm Lustgarten is an environmental reporter with ProPublica. Abrahm, thanks for joining us again.

LUSTGARTEN: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- Read Abrahm’s original story here

- Read more of Abrahm’s series “Killing the Colorado”

- Listen to another LOE interview with Abrahm on “Killing the Colorado”

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, “Like Water,” Rocket Science, Victor Lemonte Wooten/Bela Fleck (VixLix Music/Fleck Music), eOne Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Peter Boucher, Adelaide Chen, Jaime Kaiser, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. And we’re really happy to welcome Anica Green and Charlotte Rutty to our team. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth